Piedmontese Republic

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

Piedmontese Republic Repubblica Piemontese | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1798–1799 | |||||||||

| Motto: Libertà, Virtù, Eguaglianza Liberty, Virtue, Equality | |||||||||

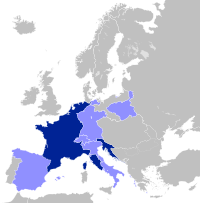

The Piedmontese Republic, surrounded by the French Republic and its other sister republics in 1799 | |||||||||

| Status | Client state of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Turin | ||||||||

| Common languages | Italian, Piedmontese | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars | ||||||||

• Established | 9 December 1798 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 20 June 1799 | ||||||||

| Currency | Piedmontese scudo | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Piedmontese Republic (Italian: Repubblica Piemontese) was a revolutionary, provisional and internationally unrecognized government established in Turin between 1798 and 1799 on the territory of Piedmont during its military rule by the French First Republic.

History

[edit]Republic of Alba

[edit]Piedmont was the main part of the Kingdom of Sardinia which, despite its name, had its core on the mainland: the densely populated and rich Principality of Piedmont, with the capital city of Turin serving as royal residence. The rulers of Piedmont simply preferred to call themselves 'Kings of Sardinia' because the title 'king' was higher in rank than 'prince'. Starting with Victor Amadeus I, the House of Savoy adopted the tradition of bestowing the title of Prince of Piedmont on the heir apparent.

The kingdom suffered a first French Revolutionary invasion in April 1796: the Montenotte campaign. After a string of French victories, Italian patriot Giovanni Antonio Ranza proclaimed a republic in the town of Alba (therefore historically known as the 'Republic of Alba') as a replacement of the Sardinian monarchy on Piedmontese territory[1] on 25 or 26 April 1796. Ranza had been agitating for an independent Piedmontese republic ever since 1793; he saw such a state as a first step towards a republic encompassing all of Italy.[1] Ranza and his fellow rebels then presented an address to French general Napoleon Bonaparte, calling on him to liberate the whole of Italy from 'tyranny'.[1] However, Bonaparte ignored their pleas, and wrote to the French Directory that the Piedmontese people were not politically ready, and that 'you should not count on a revolution in Piedmont.'[1] French military commanders at the time had no interest in this project of an Italian sister republic, and it already ended on 28 April 1796 with the Armistice of Cherasco, which gave most of Piedmont (occupying Alessandria, Coni and Tortone) back to the Sardinian king, who had to withdraw from the First Coalition. The final peace Treaty of Paris on 15 May 1796 led to loss of the duchy of Savoy, Nice, Tende and Beuil to France, and guaranteed military access to French troops crossing Piedmontese soil. The ultrashort-lived Republic of Alba would serve as the later Piedmontese Republic's predecessor.

Piedmontese revolt

[edit]When Napoleon conquered the neighbouring Republic of Genoa in June 1797 and turned it into the pro-French Ligurian Republic, democratic revolutionaries inside Piedmont began agitating for the overthrow of the Sardinian monarchy.[2] In April 1798, these Piedmontese revolutionaries launched a democratic uprising, aided by various armed bands from outside in the spring of 1798, but they were all defeated, and the Sardinian royal army executed over a hundred prisoners of war in reprisal.[2]

The Piedmontese democratic revolutionaries had to retreat, and many were forced into exile in the Ligurian Republic.[2] The Piedmontese–Sardinian regular army pursued the republican rebels into Ligurian territory, causing the Ligurian Republic to go to war against the Piedmontese monarchy in June 1798.[2]

French conquest

[edit]In early July 1798, France intervened in favour of its Ligurian sister republic, and conquered Piedmont in the course of the following months under the leadership of Barthélemy Catherine Joubert.[2]

On November, the King of Naples attacked the Roman Republic. The King of Sardinia dishonored the alliance his father signed after Cherasco, so France declared war on Piedmont. General Joubert occupied the capital of Turin on 6 December 1798. King Charles Emmanuel IV of Savoy signed a document of abdication on 8 December 1798, which also ordered his former subjects to recognise French laws and his troops to obey the orders of the French high command.[2] He went into exile in Parma, then in Tuscany, and finally moved to Cagliari on the island of Sardinia.[2] There, he issued a statement protesting his treatment by the French, and alleging that he had not signed the document of abdication out of his own free will.[2]

Establishment

[edit]

The Piedmontese Republic was declared on 9 December 1798. It was heavily dependent on France and was never really independent as it was under French military occupation. The state did not claim to be recognized, as its goal was the French annexation. The structure of administration was a provisional government.[4]

The republic used the motto Libertà, Virtù, Eguaglianza, echoing the French motto Liberté, égalité, fraternité, on its coins.[3]

Right from the start, however, its political future was in question. Some Piedmontese Jacobins favoured the development of an independent Piedmontese Republic, others wanted to unite it with the Ligurian or Cisalpine Republic, and still others including Ranza argued that the inhabitants would be best off as citizens of the French Republic rather than as citizens of a French satellite state occupied by foreign troops.[2] In the end, France decided to annex Piedmont in February 1799.[2] Jacobins opposed to annexation were dismayed by this, and a conspiracy to prevent the French annexation was planned (probably by the secretive Jacobin Società dei Raggi), but the plot was discovered by the French, and several people involved were arrested and imprisoned.[2]

Meanwhile, Britain and Russia – which were in the process of building the Second Coalition – were negotiating on how to redraw the map of Europe after defeating France in the upcoming war.[5] In September 1798, British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger argued to grant Piedmont to Austria as a reward for its participation in the upcoming war, and to act as a barrier to French expansionism in Italy.[6] In November, Foreign Secretary William Grenville added to this that Austria would get all of Piedmont, the king of Sardinia would be compensated with Tuscany and the Papal Legations (Romagna), while the Grand Duke of Tuscany (from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine) would be made ruler of the Netherlands instead.[6] However, Tsar Paul I of Russia preferred to restore Piedmont to Sardinia to check Vienna's purported territorial greed.[7] Austrian State Chancellor Thugut was fine with keeping Piedmont as a buffer between France and Austria (save for the return of the Novarese, which the Habsburgs had lost to Sardinia in 1714), and lobbied for Austrian gains elsewhere in Italy, primarily the Papal Legations.[7] By December 1798 and January 1799, the Russians and British agreed on several war aims, including the reduction of France to its pre-Revolution borders, and the restoration of the pope to the Papal States and king of Sardinia to Piedmont.[5]

Second Coalition occupation

[edit]During the Italian and Swiss expedition, the Austro–Russian troops commanded by Marshal Alexander Suvorov entered Piedmont in May 1799, and occupied Turin on 26 May 1799.[2] Following instructions given to him by Paul I, without the knowledge or consent of Austria, 'Suvorov issued proclamations calling on the Piedmontese people and army to rise and serve under him (Suvorov) in the name for their king, Charles Emmanuel,' who was still on the island of Sardinia.[7] The Austro–Russian troops defeated the Franco-Polish forces under Macdonald and Dąbrowski in the Battle of Trebbia (17–20 June 1799), affirming their hold of Piedmont. Suvorov made another statement on Paul's orders in July 1799, requesting Charles Emmanuel to return to the liberated territory of Piedmont and resume his royal reign.[7] Thugut denounced Suvorov's declarations and subjected Suvorov to his control through the Hofkriegsrat instead of Suvorov being only responsible to Emperor Francis II personally.[7] The Russians and British regarded this move as a confirmation of the Austrians' territorial greed, and grew more suspicious of their allies.[7] The anti-French revolts that occurred following Suvorov's call in May were mostly right-wing peasant movement from rural Piedmont, led by priests or former officers of the royal army.[2] Due to pressure from the Austrians, Suvorov disbanded these rebel groups in order to allow the Austrians a free hand in making a territorial settlement in northern Italy.[2] Moreover, Thugut argued to the Russians and British that Charles Emmanuel and the Piedmontese army were very unreliable allies, having abandoned Austria in 1796 and again in 1798 by concluding separate peace treaties with France.[8] He pointed out that at that moment, Piedmontese generals and troops were even serving in the French army with the king's consent.[8] Finally, Thugut insisted that liberated/conquered territories had to remain under military occupation for duation of the war to prevent interference with the war effort.[8] The issue of what to do with Piedmont led to rising tensions inside the Second Coalition, and was one of the reasons for the fatal Austrian decision to order the army of Archduke Charles out of Switzerland and into the middle Rhine area in July 1799.[9] That move is commonly regarded by historians as '[triggering] a series of military and political disasters' which would lead to the decisive French victory in the Second Battle of Zurich, motivate Russia to withdraw from the Coalition, force Austria and then the other allies to sign separate piece treaties with France and thus lead to the defeat and collapse of the Second Coalition.[10]

Subalpine Republic

[edit]Although the Piedmontese Republic was briefly reincorporated into the Kingdom of Sardinia on paper, one year later, it was reestablished as the Subalpine Republic,[3] after Napoleon took back all of northern Italy after the victorious Battle of Marengo (14 June 1800).[2] The Subalpine Republic lasted until 11 September 1802, when it was divided between the French Republic and the Italian Republic.[2] Charles Emmanuel IV abdicated again in 1802 – this time freely – in favour of his brother Victor Emmanuel I, as he had no children to succeed him.[2]

Gallery

[edit]-

1796: northern Italy before the French invasion.Kingdom of (Piedmont–)Sardinia

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Philip (2014). Napoleon: The Path to Power 1769–1799. A&C Black. pp. 292–293. ISBN 9781408854693. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Hearder, Harry (2014). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento 1790 – 1870. Routledge. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9781317872061. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b c Van Wie, Paul D. (1999). Image, History, and Politics: The Coinage of Modern Europe. Lanham: University Press of America, Inc. pp. 116–117. ISBN 0761812210.

- ^ "Satellite States - Piemontese/Subalpine Republic, 1798-1801". zum.de. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b Schroeder 1987, p. 266.

- ^ a b Schroeder 1987, p. 280–281.

- ^ a b c d e f Schroeder 1987, p. 253.

- ^ a b c Schroeder 1987, p. 254.

- ^ Schroeder 1987, p. 254–255.

- ^ Schroeder 1987, p. 245.

Literature

[edit]- Schroeder, Paul W. (1987). "The Collapse of the Second Coalition". Journal of Modern History. 59 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 244–290. doi:10.1086/243185. JSTOR 1879727. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

KSF

KSF