Play-by-mail game

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 31 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 31 min

A play-by-mail game (also known as a PBM game, PBEM game, turn-based game, turn based distance game, or an interactive strategy game.[a]) is a game played through postal mail, email, or other digital media. Correspondence chess and Go were among the first PBM games. Diplomacy has been played by mail since 1963, introducing a multi-player aspect to PBM games. Flying Buffalo Inc. pioneered the first commercially available PBM game in 1970. A small number of PBM companies followed in the 1970s, with an explosion of hundreds of startup PBM companies in the 1980s at the peak of PBM gaming popularity, many of them small hobby companies—more than 90 percent of which eventually folded. A number of independent PBM magazines also started in the 1980s, including The Nuts & Bolts of PBM, Gaming Universal, Paper Mayhem and Flagship. These magazines eventually went out of print, replaced in the 21st century by the online PBM journal Suspense and Decision.

Play-by-mail games (which became known as "turn-based games" in the digital age) have a number of advantages and disadvantages compared to other kinds of gaming. PBM games have wide ranges for turn lengths. Some games allow turnaround times of a day or less—even hourly. Other games structure multiple days or weeks for players to consider moves or turns and players never run out of opponents to face. If desired, some PBM games can be played for years. Additionally, the complexity of PBM games can be far beyond that allowed by a board game in an afternoon, and pit players against live opponents in these conditions—a challenge some players enjoy. PBM games allow the number of opponents or teams in the dozens—with some previous examples over a thousand players. PBM games also allow gamers to interact with others globally. Games with low turn costs compare well with expensive board or video games. Drawbacks include the price for some PBM games with high setup and/or turn costs, and the lack of the ability for face-to-face roleplaying. Additionally, for some players, certain games can be overly complex, and delays in turn processing can be a negative.

Play-by-mail games are multifaceted. In their earliest form they involved two players mailing each other directly by postal mail, such as in correspondence chess. Multi-player games, such as Diplomacy or more complex games available today, involve a game master who receives and processes orders and adjudicates turn results for players. These games also introduced the element of diplomacy in which participants can discuss gameplay with each other, strategize, and form alliances. In the 1970s and 1980s, some games involved turn results adjudicated completely by humans. Over time, partial or complete turn adjudication by computer became the norm. Games also involve open- and closed-end variants. Open-ended games do not normally end and players can develop their positions to the fullest extent possible; in closed-end games, players pursue victory conditions until a game conclusion. PBM games enable players to explore a diverse array of roles, such as characters in fantasy or medieval settings, space opera, inner city gangs, or more unusual ones such as assuming the role of a microorganism or a monster.

History

[edit]

The earliest play-by-mail games developed as a way for geographically separated gamers to compete with each other using postal mail. Chess and Go are among the oldest examples of this.[1] In these two-player games, players sent moves directly to each other. Multi-player games emerged later: Diplomacy is an early example of this type, emerging in 1963, in which a central game master manages the game, receiving moves and publishing adjudications.[2] According to Shannon Appelcline, there was some PBM play in the 1960s, but not much.[3] For example, some wargamers began playing Stalingrad by mail in this period.[3]

In the early 1970s, in the United States, Rick Loomis, of Flying Buffalo Inc., began a number of multi-player play-by-mail games;[4] these included games such as Nuclear Destruction, which launched in 1970.[5] This began the professional PBM industry in the United States.[6] Professional game moderation started in 1971 at Flying Buffalo which added games such as Battleplan, Heroic Fantasy, Starweb, and others, which by the late 1980s were all computer moderated.[7][b]

"Rick Loomis is generally recognized as the founder of the PBM industry."

For approximately five years, Flying Buffalo was the single dominant company in the US PBM industry until Schubel & Son entered the field in roughly 1976 with the human-moderated Tribes of Crane.[7][c] Schubel & Son introduced fee structure innovations which allowed players to pay for additional options or special actions outside of the rules. For players with larger bankrolls, this provided advantages and the ability to game the system.[7][d] The next big entrant was Superior Simulations with its game Empyrean Challenge in 1978.[7] Reviewer Jim Townsend asserted that it was "the most complex game system on Earth" with some large position turn results 1,000 pages in length.[7]

Chris Harvey started the commercial PBM industry in the United Kingdom with a company called ICBM.[12][13] After Harvey played Flying Buffalo's Nuclear Destruction game in the United States in approximately 1971, Rick Loomis suggested that he run the game in the UK with Flying Buffalo providing the computer moderation.[12] ICBM Games led the industry in the UK as a result of this proxy method of publishing Flying Buffalo's PBM games, along with KJC games and Mitregames.[13]

In the early 1980s, the field of PBM players was growing.[14] Individual PBM game moderators were plentiful in 1980.[15][e] However, the PBM industry in 1980 was still nascent: there were still only two sizable commercial PBM companies, and only a few small ones.[16] The most popular PBM games of 1980 were Starweb and Tribes of Crane.[16][f]

Some players, unhappy with their experiences with Schubel & Son and Superior Simulations, launched their own company—Adventures by Mail—with the game, Beyond the Stellar Empire, which became "immensely popular".[7] In the same way, many people launched PBM companies, trying their hand at finding the right mix of action and strategy for the gaming audience of the period. According to Jim Townsend:

In the late 70's and all of the 80's, many small PBM firms have opened their doors and better than 90% of them have failed. Although PBM is an easy industry to get into, staying in business is another thing entirely. Literally hundreds of PBM companies have come and gone, most of them taking the money of would-be-customers with them.[7]

Townsend emphasized the risks for the PBM industry in that "The new PBM company has such a small chance of surviving that no insurance company would write a policy to cover them. Skydivers are a better risk."[18] W.G. Armintrout wrote a 1982 article in The Space Gamer magazine warning those thinking of entering the professional PBM field of the importance of playtesting games to mitigate the risk of failure.[19] By the late 1980s, of the more than one hundred play-by-mail companies operating, the majority were hobbies, not run as businesses to make money.[20] Townsend estimated that, in 1988, there were about a dozen profitable PBM companies in the United States—with an additional few in the United Kingdom and the same in Australia.[20] Sam Roads of Harlequin Games similarly assessed the state of the PBM industry in its early days[g] while also noting the existence of few non-English companies.[21]

By the 1980s, interest in PBM gaming in Europe increased. The first UK PBM convention was in 1986.[22] In 1993, the founder of Flagship magazine, Nick Palmer, stated that "recently there has been a rapid diffusion throughout continental Europe where now there are now thousands of players".[23] In 1992, Jon Tindall stated that the number of Australian players was growing, but limited by a relatively small market base.[24][h] In a 2002 listing of 182 primarily European PBM game publishers and Zines, Flagship listed ten non-UK entries, to include one each from Austria and France, six from Germany, one from Greece, and one from the Netherlands.[26][i]

PBM games up to the 1980s came from multiple sources: some were adapted from existing games and others were designed solely for postal play. In 1985, Pete Tamlyn stated that most popular games had already been attempted in postal play, noting that none had succeeded as well as Diplomacy.[28] Tamlyn added that there was significant experimentation in adapting games to postal play at the time and that most games could be played by mail.[28] These adapted games were typically run by a gamemaster using a fanzine to publish turn results.[28] The 1980s were also noteworthy in that PBM games designed and published in this decade were written specifically for the genre versus adapted from other existing games.[29] Thus they tended to be more complicated and gravitated toward requiring computer assistance.[29]

The proliferation of PBM companies in the 1980s supported the publication of a number of newsletters from individual play-by-mail companies as well as independent publications which focused solely on the play-by-mail gaming industry. As of 1983, The Nuts & Bolts of PBM was the primary magazine in this market.[30] In July 1983, the first issue of Paper Mayhem was published. The first issue was a newsletter with a print run of 100.[31] Flagship began publication in the United Kingdom in October 1983, the month before Gaming Universal's first issue was published in the United States.[30] In the mid-1980s, general gaming magazines also began carrying articles on PBM and ran PBM advertisements.[32][j] PBM games were featured in magazines like Games and Analog in 1984.[30] In the early 1990s, Martin Popp also began publishing a quarterly PBM magazine in Sulzberg, Germany called Postspielbote.[33][k] The PBM genre's two preeminent magazines of the period were Flagship and Paper Mayhem.[34]

In 1984, the PBM industry created a Play-by-Mail Association.[35] This organization had multiple charter members by early 1985 and was holding elections for key positions.[35] One of its proposed functions was to reimburse players who lost money after a PBM business failed.[35]

Paul Brown, the president of Reality Simulations, Inc., estimated in 1988 that there were about 20,000 steady play-by-mail gamers, with potentially another 10–20,000 who tried PBM gaming but did not stay.[36] Flying Buffalo Inc. conducted a survey of 167 of its players in 1984. It indicated that 96% of its players were male with most in their 20s and 30s. Nearly half were white collar workers, 28% were students, and the remainder engineers and military.[37]

The 1990s brought changes to the PBM world. In the early 1990s, trending PBM games increased in complexity.[38] In this period, email also became an option to transmit turn orders and results.[39] These are called play-by-email (PBEM) games.[40] Flagship reported in 1992 that they knew of 40 PBM gamemasters on Compuserve.[41] One publisher in 2002 called PBM games "Interactive Strategy Games".[42] Turn around time ranges for modern PBM games are wide enough that PBM magazine editors now use the term "turn-based games".[43][44] Flagship stated in 2005 that "play-by-mail games are often called turn-based games now that most of them are played via the internet".[45] In the 2023 issues of Suspense & Decision, the publisher used the term "Turn Based Distance Gaming".[46]

In the early 1990s, the PBM industry still maintained some of the player momentum from the 1980s. For example, in 1993, Flagship listed 185 active play-by-mail games.[47] Patrick M. Rodgers also stated in Shadis magazine that the United States had over 300 PBM games.[48] And in 1993, the Journal of the PBM Gamer stated that "For the past several years, PBM gaming has increased in popularity."[49] That year, there were a few hundred PBM games available for play globally.[50][l] However, in 1994, David Webber, Paper Mayhem's editor in chief expressed concern about disappointing growth in the PBM community and a reduction in play by established gamers.[51] At the same time, he noted that his analysis indicated that more PBM gamers were playing less, giving the example of an average drop from 5–6 games per player to 2–3 games, suggesting it could be due to financial reasons.[52] In early 1997, David Webber stated that multiple PBM game moderators had noted a drop in players over the previous year.[53]

By the end of the 1990s, the number of PBM publications had also declined. Gaming Universal's final publication run ended in 1988.[54] Paper Mayhem ceased publication unexpectedly in 1998 after Webber's death.[55] Flagship also later ceased publication.[56][m]

The Internet affected the PBM world in various ways. Rick Loomis stated in 1999 that, "With the growth of the Internet, [PBM] seems to have shrunk and a lot of companies dropped out of the business in the last 4 or 5 years."[58] Shannon Appelcline agreed, noting in 2014 that, "The advent of the Internet knocked most PBM publishers out of business."[59] The Internet also enabled PBM to globalize between the 1990s and 2000s. Early PBM professional gaming typically occurred within single countries.[21] In the 1990s, the largest PBM games were licensed globally, with "each country having its own licensee".[21] By the 2000s, a few major PBM firms began operating globally, bringing about "The Globalisation of PBM" according to Sam Roads of Harlequin Games.[21]

By 2014 the PBM community had shrunk compared to previous decades.[60] A single PBM magazine exists—Suspense and Decision—which began publication in November 2013. The PBM genre has also morphed from its original postal mail format with the onset of the digital age. In 2010, Carol Mulholland—the editor of Flagship—stated that "most turn-based games are now available by email and online".[61] The online Suspense & Decision Games Index, as of June 2021, listed 72 active PBM, PBEM, and turn-based games.[62] In a multiple-article examination of various online turn-based games in 2004 titled "Turning Digital", Colin Forbes concluded that "the number and diversity of these games has been enough to convince me that turn-based gaming is far from dead".[63]

Advantages and disadvantages of PBM gaming

[edit]"PBM games blow the doors off of anything in the face-to-face or computer game market."

Judith Proctor noted that play-by-mail games have a number of advantages. These include (1) plenty of time—potentially days—to plan a move, (2) never lacking players to face who have "new tactics and ideas", (3) the ability to play an "incredibly complex" game against live opponents, (4) meeting diverse gamers from far-away locations, and (5) relatively low costs.[65] In 2019, Rick McDowell, designer of Alamaze, compared PBM costs favorably with the high cost of board games at Barnes & Noble, with many of the latter going for about $70, and a top-rated game, Nemesis, costing $189.[66] Andrew Greenberg pointed to the high number of players possible in a PBM game, comparing it to his past failure at attempting once to host a live eleven-player Dungeons & Dragons Game.[67][n] Flagship noted in 2005 that "It's normal to play these ... games with international firms and a global player base. Games have been designed that can involve large numbers of players – much larger than can gather for face-to-face gaming."[45] Finally, some PBM games can be played for years, if desired.[65]

Greenberg identified a number of drawbacks for play-by-mail games. He stated that the clearest was the cost, because most games require a setup cost and a fee per turn, and some games can become expensive.[67] Another drawback is the lack of face-to-face interaction inherent in play-by-mail games.[67] Finally, game complexity in some cases and occasional turn processing delays can be negatives in the genre.[67]

Description

[edit]PBM games can include Combat, Diplomacy, Politics, Exploration, Economics, and Role-Playing, with combat a usual feature and open-ended games typically the most comprehensive.[69] Jim Townsend identifies the two key figures in PBM games as the players and the moderators, the latter of which are companies that charge "turn fees" to players—the cost for each game turn.[70] In 1993, Paper Mayhem—a magazine for play-by-mail gamers—described play-by-mail games thusly:

PBM Games vary in the size of the games, turn around time, length of time a game lasts, and prices. An average PBM game has 10–20 players in it, but there are also games that have hundreds of players. Turn around time is the length of time it takes to get your turn back from a company. ... Some games never end. They can go on virtually forever or until you decide to drop. Many games have victory conditions that can be achieved within a year or two. Prices vary for the different PBM games, but the average price per turn is about $5.00.[71]

The earliest PBM games were played using the postal services of the respective countries. In 1990, the average turn-around time for a turn was 2–3 weeks.[70] However, in the 1990s, email was introduced to PBM games.[72] This was known as play-by-email (PBEM). Some games used email solely, while others, such as Hyborian War, used email as options for a portion of turn transmittal, with postal service for the remainder.[73] Other games use digital media or web applications to allow players to make turns at speeds faster than postal mail. Given these changes, the term "turn-based games" is now being used by some commentators.[43]

Mechanics

[edit]

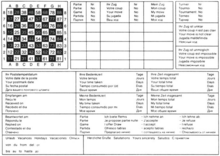

After the initial setup of a PBM game, players begin submitting turn orders. In general, players fill out an order sheet for a game and return it to the gaming company.[71] The company processes the orders and sends back turn results to the players so they can make subsequent moves.[71]

R. Danard further separates a typical PBM turn into four parts. First, the company informs players on the results of the last turn. Next players conduct diplomatic activities, if desired. Then, they send their next turns to the gamemaster (GM). Finally, the turns are processed and the cycle is repeated. This continues until the game or a player is done.[74]

Complexity

[edit]Jim Townsend stated in a 1990 issue of White Wolf Magazine that the complexity of PBM games is much higher than other types on the average.[75] He noted that PBM games at the extreme high end can have a thousand or more players as well as thousands of units to manage, while turn printouts can range from a simple one-page result to hundreds of pages (with three to seven as the average).[68][o] According to John Kevin Loth, "Novices should appreciate that some games are best played by veterans."[77] In 1986, he highlighted the complexity of Midgard with its 100-page instruction manual and 255 possible orders.[77][7] A.D. Young stated in 1982 that computers could assist PBM gamers in various ways including accounting for records, player interactions, and movements, as well as computation or analysis specific to individual games.[78]

Reviewer Jim Townsend asserted that Empyrean Challenge was "the most complex game system on Earth".[7][p] Other games, like Galactic Prisoners began simply and gradually increased in complexity.[77] As of August 2021, Rick Loomis PBM Games' had four difficulty levels: easy, moderate, hard, and difficult, with games such as Nuclear Destruction and Heroic Fantasy on the easy end and Battleplan—a military strategy game—rated as difficult.[79]

Diplomacy

[edit]According to Paper Mayhem assistant editor Jim Townsend, "The most important aspect of PBM games is the diplomacy. If you don't communicate with the other players you will be labeled a 'loner', 'mute', or just plain 'dead meat'. You must talk with the others to survive".[80] The editors of Paper Mayhem add that "The interaction with other players is what makes PBM enjoyable."[81]

Commentator Rob Chapman in a 1983 Flagship article echoed this advice, recommending that players get to know their opponents.[82] He also recommended asking direct questions of opponents on their future intentions, as their responses, true or false, provide useful information.[82] However, he advises players to be truthful in PBM diplomacy, as a reputation for honesty is useful in the long-term.[82] Chapman notes that "everything is negotiable" and advises players to "Keep your plans flexible, your options open – don't commit yourself, or your forces, to any long term strategy".[82]

Eric Stehle, owner and operator of Empire Games in 1997, stated that some games cannot be won alone and require diplomacy.[83] He suggested considering the following diplomatic points during gameplay: (1) "Know Your Neighbors", (2) "Make Sure Potential Allies Share Your Goals", (3) "Be A Good Ally", (4) "Coordinate Carefully With Your Allies", (5) "Be A Vicious Enemy", and (6) "Fight One Enemy At A Time".[83]

Game types and player roles

[edit]

Jim Townsend noted in 1990 that hundreds of PBM games were available, ranging from "all science fiction and fantasy themes to such exotics as war simulations (generally more complex world war games than those which wargamers play), duelling games, humorous games, sports simulations, etc".[70] In 1993, Steve Pritchard described PBM game types as ancient wargames, diplomacy games, fantasy wargames, power games, roleplaying games, and sports games.[84] Some PBM games defy easy categorization, such as Firebreather, which Joey Browning, the editor of the U.S. Flagship described as a "Fantasy Exploration" game.[85][q]

Play-by-mail games also provide a wide array of possible roles to play. These include "trader, fighter, explorer, [and] diplomat".[86] Roles range from pirates to space characters to "previously unknown creatures".[77] In the game Monster Island, players assume the role of a monster which explores a massive island (see image).[87] And the title of the PBM game You're An Amoeba, GO! indicates an unusual role as players struggle "in a 3D pool of primordial ooze [directing] the evolution of a legion of micro-organisms".[88][r] Loth advises that closer identification with a role increases enjoyment, but prioritizing this aspect requires more time searching for the right PBM game.[77]

Closed versus open ended

[edit]According to John Kevin Loth III, open-ended games do not end and there is no final objective or way to win the game.[77] Jim Townsend adds that, "players come and go, powers grow and diminish, alliances form and dissolve and so forth".[70] Since surviving, rather than winning, is primary, this type of game tends to attract players more interested in role-playing,[90] and Townsend echoes that open-ended games are similar to long-term RPG campaigns.[70] A drawback of this type is that mature games have powerful groups that can pose an unmanageable problem for the beginner – although some may see this situation as a challenge of sorts.[77] Examples of open ended games are Heroic Fantasy,[91] Monster Island,[92] and SuperNova: Rise of the Empire.[93] Townsend noted in 1990 that some open-ended games had been in play for up to a decade.[70]

Townsend states that "closed-ended games are like Risk or Monopoly – once they're over, they're over".[70] Loth notes that most players in closed end games start equally and the games are "faster paced, usually more intense... presenting frequent player confrontation; [and] the game terminates when a player or alliance of players has achieved specific conditions or eliminated all opposition".[77] Townsend stated in 1990 that closed-end games can have as few as ten and as many as eighty turns.[70] Examples of closed-end games are Hyborian War, It's a Crime, and Starweb.[94]

Companies in the early 1990s also offered games with both open- and closed-ended versions.[95] Additionally, games could have elements of both versions; for example, in Kingdom, an open-ended PBM game published by Graaf Simulations, a player could win by accumulating 50,000 points.[96]

Computer versus human moderated

[edit]In the 1980s, PBM companies began using computers to moderate games. This was in part for economic reasons, as computers allowed the processing of more turns than humans, but with less of a human touch in the prose of a turn result. According to John Kevin Loth III, one hundred percent computer-moderated games would also kill a player's character or empire emotionlessly, regardless of the effort invested.[77] Alternatively, Loth noted that those preferring exquisite pages of prose would gravitate toward one hundred percent human moderation.[77] Loth provided Beyond the Quadra Zone and Earthwood as popular computer-moderated examples in 1986 and Silverdawn and Sword Lords as one hundred percent human-moderated examples of the period.[77] Borderlands of Khataj is an example of a game where the company transitioned from human- to computer-moderated to mitigate issues related to a growing player base.[97]

In 1984, there was a shift toward mixed moderation—human moderated games with computer-moderated aspects such as combat.[98] Examples included Delenda est Carthago, Star Empires, and Starglobe.[99] In 1990, the editors of Paper Mayhem noted that there were games with a mix of computer and hand moderation, where games "would have the numbers run by the computer and special actions in the game would receive attention from the game master".[49]

Cost and turn processing time

[edit]Loth noted that, in 1986, $3–5 per turn was the most prevalent cost.[100] At the time, some games were free, while others cost as much as $100 per turn.[100]

PBM magazine Paper Mayhem stated that the average turn processing time in 1987 was two weeks, and Loth noted that this was also the most common.[101][100] Some companies offered longer turnaround times for overseas players or other reasons. In 1985, the publisher for Angrelmar: The Court of Kings scheduled three month turn processing times after a break in operations.[102]

In 1986, play-by-email was a nascent service only being offered by the largest PBM companies.[100] By the 1990s, players had more options for online play-by-mail games. For example, in 1995, World Conquest was available to play with hourly turns.[103] In the 21st century, many games of this genre are called turn-based games and are played via the Internet.[104]

Game turns can be processed simultaneously or serially.[105] In simultaneously processed games, the publisher processes turns from all players together according to an established sequence. In serial-processed games, turns are processed when received within the determined turn processing window.[106]

Information sources

[edit]

Rick Loomis of Flying Buffalo Games stated in 1985 that the Nuts & Bolts of PBM (first called Nuts & Bolts of Starweb) was the first PBM magazine not published by a PBM company.[107] The name changed to Nuts & Bolts of Gaming and it eventually went out of print.[107] In 1983, the U.S. PBM magazines Paper Mayhem and Gaming Universal began publication as well as Flagship in the UK. Also in 1983, PBM games were featured in magazines like Games and Analog in 1984[30] as well as Australia's gaming magazine Breakout in 1992.[108]

By 1985, Nuts & Bolts of Gaming and Gaming Universal in the U.S. were out of print. John Kevin Loth identified that, in 1986, the "three major information sources in PBM" were Paper Mayhem, Flagship, and the Play By Mail Association.[100] These sources were solely focused on play-by-mail gaming. Additional PBM information sources included company-specific publications, although Rick Loomis stated that interest was limited to individual companies".[107] Finally, play-by-mail gamers could also draw from "alliances, associations, and senior players" for information.[100]

In the mid-1980s, other gaming magazines also began venturing into PBM.[32] For example, White Wolf Magazine began a regular PBM column beginning in issue #11 as well as publishing an annual PBM issue beginning with issue #16.[109][110] The Space Gamer also carried PBM articles and reviews.[32] Additional minor information sources included gaming magazines such as "Different Worlds ... Game New, Imagine, and White Dwarf".[100] Dragon Publishing's Ares, Dragon, and Strategy and Tactics magazines provided PBM coverage along with Flying Buffalo's Sorcerer's Apprentice.[111] Gaming magazine Micro Adventurer, which closed in 1985, also featured PBM games.[112] Other PBM magazines in the late 1980s in the UK included Thrust, and Warped Sense of Humour.[113]

In the early 1990s, Martin Popp also began publishing a quarterly PBM magazine in Sulzberg, Germany called Postspielbote.[114][s] In 1995, Post & Play Unlimited stated that it was the only German-language PBM magazine.[115] In its March 1992 issue, Flagship stated that it checked Simcoarum Bimonthly for PBM news.[116][t] Shadis magazine stated in 1994 that it had begun carrying a 16-page PBM section.[118] This section, called "Post Marque", was discontinued after the March/April 1995 issue (#18), after which PBM coverage was integrated into other magazine sections.[119][u] In its January–February 1995 issue, Flagship's editor noted that their "main European competitor" PBM Scroll had gone out of print.[120]

Flagship ran into the 21st century, but ceased publication in 2010. In November 2013, online PBM journal Suspense & Decision, began publication.[121]

Fiction

[edit]Besides articles and reviews on PBM games, authors have also published PBM fiction articles according to Shannon Muir.[122] An early example called "Scapegoat" by Mike Horn appeared in the May–June 1984 issue of Paper Mayhem magazine.[123] Examples include "A Loaf of Bread" by Suzanna Y. Snow about the game A Duel of a Different Color,[124] "Dark Beginnings" by Dave Bennett about Darkness of Silverfall,[125] and Chris Harvey's "It Was the Only Thing He Could Do...", about a conglomeration of PBM games.[126] Simon Williams, the gamemaster of the PBM game Chaos Trail in 2004, also wrote an article in Flagship about the possibility of writing a PBM fiction novel.[127]

The main character of John Darnielle's 2014 novel Wolf in White Van runs a play-by-mail role-playing game.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Turn-based games (TBGs) that evolved from the PBM genre are a subset of TBGs.

- ^ John W. Kelly, Jr. and Mike Scheid also noted that Jim Dutton "decided to write a short story for each turn and the narrative game was born".[8] Kelley and Scheid did not identify the timeframe or which company Dutton worked for.

- ^ Schubel and Son first entered the PBM field in 1974.[10]

- ^ Mark Hill of Wired Magazine, stated in June 2021 that, "gamers have hated pay-to-win mechanics since the 1970s, when serious players of Tribes of Crane dropped hundreds of dollars on turns".[11]

- ^ The Space Gamer's "first annual survey of play-by-mail companies" stated that "[i]ndividual [PBM] moderators are much too numerous to list".[15]

- ^ In their April 1981 issue, the editors of The Space Gamer magazine published their 1980 Game Survey results, listing the following PBM games in order of reader ranking from 1–9: Universe II (7.2), Pellic Quest (6.3), Wofan (6.3), Starweb (6.2) The Assassin's Quest (6.0), Star Cluster Omega (6.0), Warp Force One (5.7), Nuclear Destruction (5.5), Battle Plan (5.1), Star Master (5.1), Galaxy II (5.0), The Tribes of Crane (5.0), Empyrean Challenge (4.7), Arena Combat (3.8), and Lords of Valetia (1.8).[17]

- ^ Roads did not give an exact year, but discussed a period prior to widespread use of email when PBM players used telephones to conduct diplomacy.

- ^ Flagship listed 19 Australian PBM companies in the same year.[25]

- ^ This selection does not include two listed U.S. Zines, nor does it account for countries of PBM game publishers with no listed physical address—only a web address with a .com-based URL. In a 1995 issue of Flagship, its "Galactic View" list of PBM game companies listed a Brazilian company.[27]

- ^ Loomis also noted that the Origins Awards began a "Best PBM Game" category in this period.

- ^ The magazine was published in German.

- ^ PBM commentator Patrick Rogers stated that PBM popularity was highest in the US at the time.[50]

- ^ Charles Mosteller, the editor in chief of Suspense and Decision, noted in its November 2013 inaugural issue that Flagship's final issue had been previously published without providing a date.[56] Flagship magazine's webpage lists its most recent issue (No. 130) with a copyright date of 2010.[57]

- ^ Jim Townsend stated in 1990 that PBM game participation at the high end could involve more than a thousand players.[68]

- ^ The PBM game Eressea had over 1,800 players in 2001.[76]

- ^ Vern Holford, owner of Superior Simulations, developed Empyrean Challenge, a PBM game that reviewer Jim Townsend described in 1988 as "the most complex game system on Earth" with some turn results for large positions at 1,000 pages in length.[7] According to Townsend, in those cases there was a significant investment in time to understand what happened on a turn as well as to fill out future turn orders.[7] He said a player without a spreadsheet was "nearly doomed from the outset".[7]

- ^ Browning likened Firebreather to games like Monster Island, Quest, and Lost Knowledge.

- ^ Games with unusual player types have mixed success in PBM, with Dinowars (as dinosaurs), Mall Maniacs (as a consumer), Subterranea (as an ant), and Warboid World (as a computer) proving unsuccessful, while Lizards and You're An Amoeba, GO! enjoyed more favorable results.[89]

- ^ The magazine was published in German.

- ^ The editor, Bob Bost, noted that this magazine had mainly Simcoarum Games-related content, but also some broader PBM news.[117]

- ^ Flagship also stated in its January–February 1995 issue that Shadis's "Post Marque" section was about to be closed.[120]

References

[edit]- ^ McLain 1993

- ^ Babcock 2013. p. 16.

- ^ a b Appelcline 2014. loc. 2353.

- ^ Loomis 2013. p. 38.

- ^ Rick Loomis PBM.

- ^ McLain 1993.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Townsend 1988. p. 20.

- ^ Kelley and Scheid 1985. p. 26.

- ^ The Editors 1985. p. 35.

- ^ Paper Mayhem 1984. p. 18.

- ^ Hill 2021.

- ^ a b Harvey 2003. p. 26.

- ^ a b Palmer 2003. p. 4.

- ^ Harvey 1984. p. 21.

- ^ a b The Space Gamer 1980. p. 13.

- ^ a b Popolizio, Leblanc, and Popolizio 1990. p. 8.

- ^ The Space Gamer 1981. p. 9.

- ^ Townsend 1989. p. 55.

- ^ Armintrout 1982. pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Townsend 1988. p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Roads 2003. p. 40.

- ^ Mulholland 1989. p. 1.

- ^ Palmer 1993.

- ^ Tindall 1992. p. 12.

- ^ Flagship Editors 1992. p. 53.

- ^ Flagship Editors 2020. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Flagship Editors 1995. p. 48.

- ^ a b c Tamlyn 19853. p. 33.

- ^ a b Croft 1985. p. 41.

- ^ a b c d McClain 1985. p. 38.

- ^ Webber 1987. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Loomis 1985. p. 35.

- ^ Flagship Editors 1992. p. 14.

- ^ Paduch 1993. p. RC21.

- ^ a b c Gray 1985. p. 38.

- ^ Dias 1988. p. 33.

- ^ Loomis 1984. p. 4.

- ^ Paduch 1993 p. 2.

- ^ Mills 1994 p. 4.

- ^ Palmer 1984. p. 23.

- ^ Proctor 1992. p. 23.

- ^ Editors 2002.

- ^ a b Mosteller 2014. p. 76.

- ^ Mulholland 2010. p. 43.

- ^ a b Flagship 2005. p. 5.

- ^ Capps 2023. Cover.

- ^ Procter 1993. p. 51.

- ^ Rodgers 1994. p. 91.

- ^ a b Paper Mayhem 1993. p. 4.

- ^ a b Rogers 1993. p. 40.

- ^ Webber 1994 p. 2

- ^ Webber 1994. p. 2.

- ^ Webber 1997. p. 4.

- ^ Webber 1988. p. 2

- ^ Muir 2013. p. 14

- ^ a b Mosteller 2014. p. 29.

- ^ Flagship 2011; Flagship 2010. p. 3

- ^ Loomis 1999. p. 5.

- ^ Appelcline 2014. loc. 2706.

- ^ Mosteller 2014. p. 33

- ^ Mulholland 2010. p. 42.

- ^ Zachary 2021.

- ^ Forbes 2004. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Townsend 1988. p. 47.

- ^ a b Procter 1993. p. 51.

- ^ McDowell 2019. p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Greenberg 1993. p. 8–9.

- ^ a b Townsend 1990 pp. 18–19.

- ^ Kaiser 1983. p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Townsend 1990 p. 19.

- ^ a b c Paper Mayhem Jan/Feb 1993. p. 1.

- ^ Paduch 1993. p. 2.

- ^ Reality Simulations, Inc.

- ^ danard.net 2020.

- ^ Townsend 1990. p. 18.

- ^ Lindahl 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k John Kevin Loth III 1986. p. 42.

- ^ Young 1982. p. 36.

- ^ Rick Loomis PBM Games 2021.

- ^ Townsend 1987. p. 29.

- ^ Paper Mayhem 1990. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Chapman 1983. p. 12.

- ^ a b Stehle 1997. p. 7.

- ^ Pritchard 1993. p. 31.

- ^ Browning 1993. p. 13.

- ^ Freitas 1990. p. 47.

- ^ Helzer 1993. p. 12.

- ^ Paper Mayhem 1994. p. 42.

- ^ Editors 1995. p. 9.

- ^ Croft 1985. p. 42.

- ^ Townsend 1987. p. 24.

- ^ DuBois 1997. p. 4.

- ^ Suspense & Decision 2019. pp. 35–40.

- ^ Lindahl 2020

- ^ Paper Mayhem 1993. p. 5.

- ^ Paper Mayhem 1993. p. 21.

- ^ Browning 1994. p. 6.

- ^ Armintrout 1984. p. 43.

- ^ Mulholland 1989. pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g John Kevin Loth III 1986. p. 43.

- ^ Paper Mayhem Sep/Oct 1987. p. 1.

- ^ Editors 1985 p. 47.

- ^ Browning 1995 p. 6.

- ^ Flagship 2005 p. 5.

- ^ McDowell 2014. p. 5.

- ^ McDowell 2014. pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Loomis 1985. p. 36.

- ^ Thomas 1992. p. 21.

- ^ White Wolf 1988. p. 2.

- ^ White Wolf 1989. p. 1.

- ^ Gray 1983. p. 30.

- ^ Flagship Editors 1985. p. 44.

- ^ Woods 1989. p. 63.

- ^ Flagship Editors 1992. p. 14.

- ^ Post & Play Unlimited 1995. p. 29.

- ^ Bost 1992. p. 9.

- ^ Bost 1992. p. 10.

- ^ Shadis 1994. p. 47.

- ^ Rodgers 1995. p. 93.

- ^ a b Browning 1995. p. 7.

- ^ Suspense & Decision 2013.

- ^ Muir 1994. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Horn 1984. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Snow 1995. p. 56.

- ^ Bennett 1995. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Harvey 1984. p. 26.

- ^ Williams 2004. p. 39.

Bibliography

[edit]- Appelcline, Shannon (2014). Designers & Dragons: The 70s: A History of the Roleplaying Game Industry. Evil Hat Productions, LLC. ASIN B00R8RB656.

- Armintrout, W.G. (September 1982). "Playtesting Your PBM". The Space Gamer. No. 55. pp. 31–32.

- Armintrout, W.G. (January–February 1984). "A Gentle Art: Human-Moderated PBMs". The Space Gamer. No. 67. pp. 42–43.

- Babcock, Chris (December 2013). "Diplomacy" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 2. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Bennett, Dave (March–April 1995). "Dark Beginnings". Paper Mayhem. No. 71. pp. 57–58.

- Bost, Bob (March 1992). "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 36 (U.S. ed.). pp. 9–12.

- Browning, Joey (November–December 1993). "Firebreather: High Quality, Low Challenge". Flagship. No. 46 (U.S. ed.). pp. 13–14.

- Browning, Joey (July–August 1994). "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 50. U.S. Edition. pp. 6–9.

- Browning, Joey (January–February 1995). "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 53. U.S. Edition. p. 7.

- Capps, Jon (January–February 2023). "Suspense & Decision". Suspense & Decision. No. 23. Talisman Consulting. p. Cover.

- Chapman, Rob (Winter 1983). "How to Win at PBM". Flagship. No. 1. p. 12.

- "Contents". White Wolf Magazine. No. 11. White Wolf Publishing. 1988. p. 2.

- "Credits". White Wolf Magazine. No. 16. White Wolf Publishing. June–July 1989. p. 1.

- Croft, Martin (June 1985). "Play-By-Mail Games". Computer Gamer. No. 3. p. 42. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Dag Weber Briefspiele (January–February 1995). "You Still Have to Wait!". Flagship. No. 53. U.S. Edition. p. 29.

- Dias, Dan (December 1997 – January 1998). "Bring Me the Head of Paul Brown". D2 Report. No. 15. p. 3.

- Danard, R. (2022). "Play-by-mail: Overview". jpc.danard.net. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Diplomacy". The Journal of the PBM Gamer (4th ed.). Paper Mayhem. 1990. p. 3.

- DuBois, Steven (January–February 1997). "Monster Island: A Review". Paper Mayhem. No. 82. p. 4.

- Editors (July–August 1985). "Rick Loomis on Play-By-Mail [Editor Intro]". The Space Gamer. No. 75. p. 35.

- Editors (April 1981). "1980 Game Survey Results". The Space Gamer. No. 38. p. 8.

- Editors (September–October 1985). "PBM News Briefs". The Space Gamer. No. 76. p. 47.

- Editors (May–June 1995). "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 55. p. 9.

- Editors (2002). "Star Fleet Warlord". Agents of Gaming. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Flagship: The Independent Magazine for Gamers; Issue 130 PDF". Skeletal Software Ltd. 2007–2011. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Freitas, Werner (August–September 1990). "PBM Corner: Role Playing in Play-by-Mail Games". White Wolf Magazine. No. 22. p. 47.

- Flagship Editors (February–March 2005). "Turn-Based Gaming" (PDF). Flagship. No. 112. p. 5. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Flagship Editors (Summer 1985). "The Gaming Universal Fold". Flagship. No. 7. p. 44.

- Flagship Editors (March 1992). "Galactic View". Flagship. No. 36. U.S. Edition. p. 54.

- Flagship Editors (January–February 1995). "Galactic View". Flagship. No. 53. U.S. Edition. pp. 48–50.

- Forbes, Colin (October–November 2004). "Turning Digital" (PDF). Flagship. No. 110. pp. 14–15. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- "[Front matter]". Paper Mayhem. No. 26. September–October 1987. p. 1.

- "Galactic View" (PDF). Flagship. No. 99. October–November 2002. pp. 50–51. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- "Gameline News and Updates". Paper Mayhem. No. 6. May–June 1984. pp. 18–20.

- "Graaf Simulations". The Journal of the PBM Gamer (7th ed.). Paper Mayhem. 1993. p. 21.

- Gray, Mike (April 1983). "The PBM Scene: Facts You Can Use When YOU Choose What Game to Play". Dragon. No. 72. pp. 30–36.

- Gray, Mike (April 1985). "PBM Update: News & Views". Dragon. No. 96. pp. 38–41.

- Greenberg, Andrew (May–June 1993). "PBM Corner: A Beginning in Play-By-Mail; Is It Worth It?". White Wolf Magazine. No. 36. pp. 8–9.

- Harvey, Chris (Spring 1984). "The Future of PBM". Flagship. No. 2. p. 21.

- Harvey, Chris (April–May 2003). "My Life in Games" (PDF). Flagship. No. 102. p. 26. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- Harvey, Chris (Summer 1984). "Turn-Based Gaming" (PDF). Flagship. No. 3. p. 26. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- Helzer, Herb (January–February 1993). "Monster Island: Just One Destination for PBM Company". Paper Mayhem. No. 58. p. 12.

- Hill, Mark (June 20, 2021). "Remember When Multiplayer Gaming Needed Envelopes and Stamps?". Wired. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Horn, Mike (May–June 1984). "Scapegoat". Paper Mayhem. No. 6. pp. 13–14.

- Kaiser, Mark (November–December 1983). "Behind the Lines". PBM Universal. No. 1. pp. 25–26.

- Kelly, Jr, John W.; Scheid, Mike (May–June 1985). "Prehistoric PBM: First World in Review". Paper Mayhem. No. 12. p. 26.

- Lindahl, Greg. "Eressea". Play by Email (PBeM) & Play by Mail (PBM) List Index. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- Lindahl, Greg. "PBM / PBEM List Index: Closed-Ended". Play by Email (PBeM) & Play by Mail (PBM) List Index. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Loomis, Rick (October 1984). "Survey Results from FBQ#49". Flying Buffalo Quarterly. No. 50. p. 4.

- Loomis, Rick (July–August 1985). "Rick Loomis on Play-By-Mail". The Space Gamer. No. 75. pp. 35–36.

- Loomis, Rick (May 1999). "The History of Play-by-Mail and Flying Buffalo" (PDF). Flying Buffalo Quarterly. No. 79. pp. 2–5. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Loomis, Rick (December 2013). "Letter from Rick Loomis to the Play By Mail/Email/Web/Turn Based Games Community" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 2. p. 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Loth III, John Kevin (March–April 1986). "A PBM Primer". Paper Mayhem. No. 17. p. 42.

- Loth III, John Kevin (March–April 1986). "A PBM Primer". Paper Mayhem. No. 17. p. 43.

- McDowell, Rick (August 2019). "Why Should We Care About PBM? Is the Future of this Hobby Past?" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 18. playbymail.net. pp. 42–43. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- McClain, Bob (May–June 1985). "The Rise and Fall of Gaming Universal". Space Gamer. No. 74. pp. 38–39.

- McDowell, Rick (May 2014). "What's Your Game? Top Tier Episodic Strategy Game (PBEM) Design Considerations". Suspense & Decision. No. 7. pp. 4–6. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- McLain, Bob (August 1, 1993). "Play By Mail: The Infancy of Cyberspace". Pyramid. sjgames.com. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- Mills, Craig William (July–August 1994). "How Will You Keep Them Down on the Farm? Or Why My Mail Fix Doesn't Thrill Me the Way it Used To". Flagship. No. 50. U.S. Edition. pp. 4–5.

- Mosteller, Charles (June 2014). "An Open Invitation To the Player Base of Turn-Based Games" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 8. p. 76. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- Mosteller, Charles (November 2013). "Hyborian War: A Mindblowing Experience?!" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 1. PlayByMail.net. p. 24. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- Mosteller, Charles (November 2013). "A Journey Together Awaits" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 1. PlayByMail.net. pp. 29–34. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- Muir, Shannon (September–October 1994). "PBM Fiction: Why Write It, Why Read It, Who Needs It?". Paper Mayhem. No. 68. pp. 29–30.

- Muir, Shannon (December 2013). "Using Play By Mail in a Novel's Plot: The Story Behind for the Love of Airagos" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 5. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Muir, Shannon; Muir, John C. (November 2001). "Thoughts on the Evolution of PBM". Sabledrake Magazine. Archived from the original on June 17, 2002. Retrieved April 19, 2010 – via Wayback Machine. Interview with John C. Muir, long-time PBM author.

- Mulholland, Carol; Mulholland, Ken (1989). Games Mastership: How to Design and Run a Play-By-Mail Game. Time Patterns.

- Mulholland, Carol (2010). "Carol's Logbook" (PDF). Flagship. No. 130. p. 43. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- Mulholland, Carol (2010). "Carol's Logbook" (PDF). Flagship. No. 129. p. 42. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- Mulholland, Carol (2010). "In this Issue... (Front matter)" (PDF). Flagship. No. 130. TimePatterns. p. 3. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- "Nuclear Destruction". Rick Loomis PBM Games. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- Paduch, Sally (June 27, 1993). "Email Brings Immediacy to Play-By-Mail Games". New York Times. p. RC21.

- Palmer, Nicky (Autumn 1984). "PBEM". Flagship. No. 4. pp. 23–24. 1984 article on the prospects of PBEM with assembled evidence from PBM figures such as Rick Loomis.

- Palmer, Nicky (January 2003). "Flagship 100: A Founder's Memories" (PDF). Flagship. No. 100. p. 4. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- Pehr, Ronald (November 1980). "Fantasies By Mail". The Space Gamer. No. 33. p. 12.

- Popolizio, Mike; LeBlanc, Liz; Popolizio, Marti (January–February 1990). "Revamping a Classic! The Redesign of BSE". Paper Mayhem. No. 40. pp. 8–10.

- Pritchard, Steve (May 1993). "There's No Way I'm Playing That!". Flagship. No. 43. pp. 31–32.

- Proctor, Judith (March–April 1993). "The PBM Corner". White Wolf Magazine. No. 35. p. 51.

- Proctor, Judith (March 1992). "You Bash the Balrog!". Flagship. No. 36. U.S. Edition. p. 37. Article about PBM on email and Compuserve.

- "PBM &/or E-Mail Games". Rick Loomis PBM Games. August 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "PBM Game Listing". The Journal of the PBM Gamer: What is PBM Gaming? (7th ed.). Paper Mayhem. 1993. p. 4.

- Reality Simulations Inc. "Hyborian War E-Mail Turns". Reality.com. Reality Simulations. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Roads, Sam (September–October 2003). "The Globalisation of PBM" (PDF). Flagship. No. 104. p. 40. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- Rodgers, Patrick M. (September 1993). "Welcome to the World of Play-by-Mail Gaming". Shadis. No. 9. The Alderac Group. pp. 40–42.

- Rodgers, Patrick M. (July–August 1994). "Welcome to Play-by-Mail (PBM) Gaming". Shadis. No. 14. The Alderac Group. p. 91.

- Rodgers, Patrick M. (January–February 1995). "Post Marque Special Play-By-Mail Section". Shadis. No. 17. p. 93.

- Saligari (July–September 1993). "Interview with a Reporter". Agonistika News. The PBM Locomotive. Archived from the original on 18 April 2001. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- Shadis (May–June 1995). "Shadis". Flagship. No. 55. U.S. Edition. p. 47.

- Snow, Suzanne Y. (March–April 1995). "A Loaf of Bread". Paper Mayhem. No. 71. p. 56.

- Stehle, Eric (May–June 1997). "Play-By-Mail Diplomacy Strategies". Paper Mayhem. No. 84. p. 7.

- "Suspense and Decision Magazine: A PBM Magazine for the 21st Century!". www.playbymail.net. 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "Suspense and Decision Magazine: A PBM Magazine for the 21st Century!" (PDF). www.playbymail.net. November 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- Tamlyn, Pete (Spring 1985). "Adapting Games for Postal Play". Flagship. No. 6. p. 33.

- "The Land of Karrus [Advertisement]". Paper Mayhem. No. 85. July–August 1997. p. 27.

- Thomas, Cameron (March 1992). "Warriors and Wizards". Flagship. No. 36. U.S. Edition. pp. 21–24.

- Tindall, Jon (March 1992). "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 36. U.S. Edition. p. 12.

- "The Spokesmen Speak". Flagship. No. 35. January 1992. p. 14.

- Townsend, Jim (January–February 1987). "How to Win in PBM—An Organizational Viewpoint". Paper Mayhem. No. 22. p. 29.

- Townsend, Jim (March–April 1987). "A Real Look at Heroic Fantasy". Paper Mayhem. No. 23. p. 24.

- Townsend, Jim (1988). "The PBM Corner". White Wolf. No. 9. p. 47.

- Townsend, Jim (1988). "The PBM Corner". White Wolf Magazine. No. 11. p. 20.

- Townsend, Jim (1988). "The PBM Corner". White Wolf Magazine. No. 12. p. 19.

- Townsend, Jim (February 1989). "The PBM Corner". White Wolf Magazine. No. 14. p. 55.

- Townsend, Jim (June–July 1990). "PBM Corner: PBM For Beginners". White Wolf Magazine. No. 21. pp. 18–19.

- "TSG Surveys: Play-By-Mail Game Companies". The Space Gamer. No. 33. November 1980. p. 13.

- Paper Mayhem (January–February 1993). "Front Matter". Paper Mayhem. No. 58. p. 1.

- Proctor, Judith (March–April 1993). "PBM Corner: Not Just for a Dull Evening". White Wolf Magazine. No. 35. p. 51.

- Webber, David (July–August 1987). "Where We're Heading…". Paper Mayhem. No. 25. p. 2.

- Webber, David (March–April 1988). "Where We're Headed". Paper Mayhem. No. 29. p. 2.

- Webber, David (Mar–Apr 1994). "Where We're Headed". Paper Mayhem. No. 65. p. 2.

- Webber, David (March–April 1997). "Where We're Heading...". Paper Mayhem. No. 83. p. 4.

- Woods, John (October 1989). "PBM Update". The Games Machine. No. 23. p. 63.

- Young, A.D. (September 1982). "Deus Ex Machina: Utility Programs for PBM Gamers". The Space Gamer. No. 55. pp. 36–37.

- "You're An Amoeba, GO! [Advertisement]". Paper Mayhem. No. 68. September–October 1994. p. 42.

- Williams, Simon (January 2004). "PBM Fiction" (PDF). Flagship. No. 105. p. 39. Retrieved October 22, 2020. Magazine date: December–January 2003/2004.

- Zachary, Raven (September 2019). "Be More than a Player: Learning by Teaching in SuperNova & Middle-Earth" (PDF). Suspense and Decision. No. 19. playbymail.net. pp. 35–40. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- Zachary, Raven (June 27, 2021). "The Suspense & Decision Games Index". Suspense and Decision. playbymail.net. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Armintrout, W.G. (November 1982). "The Great Buffalo Hunt: Heroic Fantasy vs. Catacombs of Chaos". The Space Gamer. No. 57. pp. 2–5. Early reviews of one game each by two of the larger PBM publishers of the period.

- Brown, Jean (January–February 1991). "What is Play-By-Mail Gaming?". American Gamer. No. 2. p. 6.

- Cate III, Henry (1983). "Starting a PBM Business". Nuts & Bolts of Gaming. Vol. 3, no. 14. pp. 16–17.

- Derbacher, C.L. (1983). "What Makes a PBM Gamemaster Tick?". Nuts & Bolts of Gaming. Vol. 3, no. 16. pp. 26–27.

- Derbacher, C.L. (1983). "PBM Game Players: Who Are They? What Games Do They Play?". Nuts & Bolts of Gaming. Vol. 3, no. 17. p. 15.

- Myers, David (November 1982). "The Worm: Or, Why Do I Doubt It? Because I Keep My Own Promises...". The Space Gamer. No. 57. pp. 12–15. Fiction article about a space-based PBM game called Star Battle Forever.

- Spencer, David and Shannon Muir Broden (April 16, 2021). "Paper Mayhem: A Critical Resource During the Heyday of PBM Gaming". Suspense & Decision. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- Spencer, David (4 September 2022). "Flagship Magazine: Spanning Two Millenia of Play-by-Mail Gaming". Suspense & Decision. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- Spencer, David (2022). "Small Starts: A Look into a 1980s Play-by-Mail Magazine—the Nuts & Bolts of Gaming". Suspense & Decision. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Greg Lindahl (10 August 2020). "Play by Email (PBeM) & Play by Mail (PBM) List Index". www.pbm.com. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Suspense & Decision: A PBM Magazine for the 21st Century". 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- Talisman Games (2021). "About Turn-Based Games". Talisman Games. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

KSF

KSF