Political economy

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

| Part of the behavioral sciences |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

|

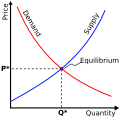

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government).[1][2][3][4] Widely-studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour and international markets, as well as phenomena such as growth, distribution, inequality, and trade, and how these are shaped by institutions, laws, and government policy. Originating in the 18th century, it is the precursor to the modern discipline of economics.[5][6] Political economy in its modern form is considered an interdisciplinary field, drawing on theory from both political science and modern economics.[4]

Political economy originated within 16th century western moral philosophy, with theoretical works exploring the administration of states' wealth – political referring to polity, and economy derived from Greek οἰκονομία "household management". The earliest works of political economy are usually attributed to the British scholars Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo, although they were preceded by the work of the French physiocrats, such as François Quesnay, Richard Cantillon and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot.[7] Varied thinkers Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx saw economics and politics as inseparable.[8]

In the late 19th century, the term economics gradually began to replace the term political economy with the rise of mathematical modeling coinciding with the publication of the influential textbook Principles of Economics by Alfred Marshall in 1890. Earlier, William Stanley Jevons, a proponent of mathematical methods applied to the subject, advocated economics for brevity and with the hope of the term becoming "the recognised name of a science".[9][10] Citation measurement metrics from Google Ngram Viewer indicate that use of the term economics began to overshadow political economy around roughly 1910, becoming the preferred term for the discipline by 1920.[11] Today, the term economics usually refers to the narrow study of the economy absent other political and social considerations while the term political economy represents a distinct and competing approach.

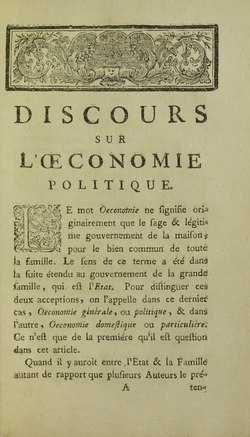

Etymology

[edit]Originally, political economy meant the study of the conditions under which production or consumption within limited parameters was organized in nation-states. In that way, political economy expanded the emphasis on economics, which comes from the Greek oikos (meaning "home") and nomos (meaning "law" or "order"). Political economy was thus meant to express the laws of production of wealth at the state level, quite like economics concerns putting home to order. The phrase économie politique (translated in English to "political economy") first appeared in France in 1615 with the well-known book by Antoine de Montchrétien, Traité de l'economie politique. Other contemporary scholars attribute the roots of this study to the 13th Century Tunisian Arab Historian and Sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, for his work on making the distinction between "profit" and "sustenance", in modern political economy terms, surplus and that required for the reproduction of classes respectively. He also calls for the creation of a science to explain society and goes on to outline these ideas in his major work, the Muqaddimah. In Al-Muqaddimah Khaldun states, "Civilization and its well-being, as well as business prosperity, depend on productivity and people's efforts in all directions in their own interest and profit" – seen as a modern precursor to Classical Economic thought.

Leading on from this, the French physiocrats were the first major exponents of political economy,[12] although the intellectual responses[13] of Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, Henry George and Karl Marx to the physiocrats generally receive much greater attention.[14] The world's first professorship in political economy was established in 1754 at the University of Naples Federico II in southern Italy. The Neapolitan philosopher Antonio Genovesi was the first tenured professor. In 1763, Joseph von Sonnenfels was appointed a Political Economy chair at the University of Vienna, Austria. Thomas Malthus, in 1805, became England's first professor of political economy, at the East India Company College, Haileybury, Hertfordshire. At present, political economy refers to different yet related approaches to studying economic and related behaviours, ranging from the combination of economics with other fields to the use of different, fundamental assumptions challenging earlier economic assumptions.

Current approaches

[edit]

Political economy most commonly refers to interdisciplinary studies drawing upon economics, sociology and political science in explaining how political institutions, the political environment, and the economic system—capitalist, socialist, communist, or mixed—influence each other.[15] The Journal of Economic Literature classification codes associate political economy with three sub-areas: (1) the role of government and/or class and power relationships in resource allocation for each type of economic system;[16] (2) international political economy, which studies the economic impacts of international relations;[17] and (3) economic models of political or exploitative class processes.[18] Within political science, a general distinction is made between international political economy typically examined by scholars of international relations and comparative political economy, which is primarily studied by scholars of comparative politics.[1]

Public choice theory is a microfoundations theory closely intertwined with political economy. Both approaches model voters, politicians and bureaucrats as behaving in mainly self-interested ways, in contrast to a view, ascribed to earlier mainstream economists, of government officials trying to maximize individual utilities from some kind of social welfare function.[19] As such, economists and political scientists often associate political economy with approaches using rational-choice assumptions,[20] especially in game theory[21] and in examining phenomena beyond economics' standard remit, such as government failure and complex decision making in which context the term "positive political economy" is common.[22] Other "traditional" topics include analysis of such public policy issues as economic regulation,[23] monopoly, rent-seeking, market protection,[24] institutional corruption[25] and distributional politics.[26] Empirical analysis includes the influence of elections on the choice of economic policy, determinants and forecasting models of electoral outcomes, the political business cycles,[27] central-bank independence and the politics of excessive deficits.[28] An interesting example would be the publication in 1954 of the first manual of Political Economy in the Soviet Union, edited by Lev Gatovsky, which mixed the classic theoretical approach of the time with the soviet political discourse.[29]

A rather recent focus has been put on modeling economic policy and political institutions concerning interactions between agents and economic and political institutions,[30] including the seeming discrepancy of economic policy and economist's recommendations through the lens of transaction costs.[31] From the mid-1990s, the field has expanded, in part aided by new cross-national data sets allowing tests of hypotheses on comparative economic systems and institutions.[32] Topics have included the breakup of nations,[33] the origins and rate of change of political institutions in relation to economic growth,[34] development,[35] financial markets and regulation,[36] the importance of institutions,[37] backwardness,[38] reform[39] and transition economies,[40] the role of culture, ethnicity and gender in explaining economic outcomes,[41] macroeconomic policy,[42] the environment,[43] fairness[44] and the relation of constitutions to economic policy, theoretical[45] and empirical.[46]

Other important landmarks in the development of political economy include:

- New political economy which may treat economic ideologies as the phenomenon to explain, per the traditions of Marxian political economy. Thus, Charles S. Maier suggests that a political economy approach "interrogates economic doctrines to disclose their sociological and political premises.... in sum, [it] regards economic ideas and behavior not as frameworks for analysis, but as beliefs and actions that must themselves be explained".[47] This approach informs Andrew Gamble's The Free Economy and the Strong State (Palgrave Macmillan, 1988), and Colin Hay's The Political Economy of New Labour (Manchester University Press, 1999). It also informs much work published in New Political Economy, an international journal founded by Sheffield University scholars in 1996.[48]

- International political economy (IPE) an interdisciplinary field comprising approaches to the actions of various actors. According to International Relations scholar Chris Brown, University of Warwick professor, Susan Strange, was "almost single-handedly responsible for creating international political economy as a field of study."[49] In the United States, these approaches are associated with the journal International Organization, which in the 1970s became the leading journal of IPE under the editorship of Robert Keohane, Peter J. Katzenstein and Stephen Krasner. They are also associated with the journal The Review of International Political Economy. There also is a more critical school of IPE, inspired by thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci and Karl Polanyi; two major figures are Matthew Watson and Robert W. Cox.[50]

- The use of a political economy approach by anthropologists, sociologists, and geographers used in reference to the regimes of politics or economic values that emerge primarily at the level of states or regional governance, but also within smaller social groups and social networks. Because these regimes influence and are influenced by the organization of both social and economic capital, the analysis of dimensions lacking a standard economic value (e.g. the political economy of language, of gender, or of religion) often draws on concepts used in Marxian critiques of capital. Such approaches expand on neo-Marxian scholarship related to development and underdevelopment postulated by André Gunder Frank and Immanuel Wallerstein.

- Historians have employed political economy to explore the ways in the past that persons and groups with common economic interests have used politics to effect changes beneficial to their interests.[51]

- Political economy and law is a recent attempt within legal scholarship to engage explicitly with political economy literature. In the 1920s and 1930s, legal realists (e.g. Robert Hale) and intellectuals (e.g. John Commons) engaged themes related to political economy. In the second half of the 20th century, lawyers associated with the Chicago School incorporated certain intellectual traditions from economics. However, since the crisis in 2007 legal scholars especially related to international law, have turned to more explicitly engage with the debates, methodology and various themes within political economy texts.[52][53]

- Thomas Piketty's approach and call to action which advocated for the re-introduction of political consideration and political science knowledge more generally into the discipline of economics as a way of improving the robustness of the discipline and remedying its shortcomings, which had become clear following the 2008 financial crisis.[54]

- In 2010, the only Department of Political Economy in the United Kingdom formally established at King's College London. The rationale for this academic unit was that "the disciplines of Politics and Economics are inextricably linked", and that it was "not possible to properly understand political processes without exploring the economic context in which politics operates".[55]

- In 2012, the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) was founded at The University of Sheffield by professors Tony Payne and Colin Hay. It was created as a means of combining political and economic analyses of capitalism which were viewed by the founders to be insufficient as independent disciplines in explaining the 2008 financial crisis.[56]

- In 2017, the Political Economy UK Group (abbreviated PolEconUK) was established as a research consortium in the field of political economy. It hosts an annual conference and counts among its member institutions Oxford, Cambridge, King's College London, Warwick University and the London School of Economics.[57]

Related disciplines

[edit]Because political economy is not a unified discipline, there are studies using the term that overlap in subject matter, but have radically different perspectives:[58]

- Politics studies power relations and their relationship to achieving desired ends.

- Philosophy rigorously assesses and studies a set of beliefs and their applicability to reality.

- Economics studies the distribution of resources so that the material wants of a society are satisfied; enhance societal well-being.

- Sociology studies the effects of persons' involvement in society as members of groups and how that changes their ability to function. Many sociologists start from a perspective of production-determining relation from Karl Marx.[citation needed] Marx's theories on the subject of political economy are contained in his book Das Kapital.

- Anthropology studies political economy by investigating regimes of political and economic value that condition tacit aspects of sociocultural practices (e.g. the pejorative use of pseudo-Spanish expressions in the U.S. entertainment media) by means of broader historical, political and sociological processes. Analyses of structural features of transnational processes focus on the interactions between the world capitalist system and local cultures.[citation needed]

- Archaeology attempts to reconstruct past political economies by examining the material evidence for administrative strategies to control and mobilize resources.[59] This evidence may include architecture, animal remains, evidence for craft workshops, evidence for feasting and ritual, evidence for the import or export of prestige goods, or evidence for food storage.

- Psychology is the fulcrum on which political economy exerts its force in studying decision making (not only in prices), but as the field of study whose assumptions model political economy.

- Geography studies political economy within the wider geographical studies of human-environment interactions wherein economic actions of humans transform the natural environment. Apart from these, attempts have been made to develop a geographical political economy that prioritises commodity production and "spatialities" of capitalism.

- History documents change, often using it to argue political economy; some historical works take political economy as the narrative's frame.

- Ecology deals with political economy because human activity has the greatest effect upon the environment, its central concern being the environment's suitability for human activity. The ecological effects of economic activity spur research upon changing market economy incentives. Additionally and more recently, ecological theory has been used to examine economic systems as similar systems of interacting species (e.g., firms).[60]

- Cultural studies examines social class, production, labor, race, gender and sex.

- Communications examines the institutional aspects of media and telecommunication systems. As the area of study focusing on aspects of human communication, it pays particular attention to the relationships between owners, labor, consumers, advertisers, structures of production and the state and the power relationships embedded in these relationships.

Journals

[edit]- Constitutional Political Economy

- Economics & Politics. ISSN 0954-1985

- European Journal of Political Economy.

- Latin American Perspectives

- International Journal of Political Economy

- Journal of Australian Political Economy. ISSN 0156-5826

- New Political Economy

- Public Choice.

- Studies in Political Economy

See also

[edit]- Critique of political economy

- Economic sociology

- Economic study of collective action

- Constitutional economics

- European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy (EAEPE)

- Economic ideology

- Institutional economics

- Land value tax

- Law of rent

- Important publications in political economy

- Marxian political economy

- Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought

- Political ecology

- Political economy in anthropology

- Political economy of climate change

- Social model

- Social capital

- Socioeconomics

- Surplus economics

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Hacker, Jacob S.; Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander; Pierson, Paul; Thelen, Kathleen (2021), Hertel-Fernandez, Alexander; Hacker, Jacob S.; Thelen, Kathleen; Pierson, Paul (eds.), "The American Political Economy: A Framework and Agenda for Research", The American Political Economy: Politics, Markets, and Power, Cambridge University Press, pp. 4–5, ISBN 978-1-316-51636-2, archived from the original on 2022-05-03, retrieved 2022-06-18

- ^ Bladen, Vincent (2016). An Introduction to Political Economy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442632103. OCLC 1013947543.

- ^ Mill, John Stuart, 1806–1873. (2009). Principles of political economy : with some of their applications to social philosophy. Bibliolife. ISBN 978-1116761184. OCLC 663099414.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "political economy | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ "economics | Definition, History, Examples, Types, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-15. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ Weingast, Barry R.; Wittman, Donald A. (2011-07-07). "Overview Of Political Economy". The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. pp. 784–809. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0038. ISBN 978-0-19-960445-6. Archived from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ Steiner (2003), pp. 61–62

- ^ Fishkin, Joseph; Forbath, William E. (2022-02-08). The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution: Reconstructing the Economic Foundations of American Democracy. Harvard University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-674-24740-6.

- ^ Jevons, W. Stanley. The Theory of Political Economy, 1879, 2nd ed. p. xiv. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Groenwegen, Peter. (1987 [2008]). "'political economy' and 'economics'", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 905–906. [Pp. 904–07.]

- ^ Mark Robbins (2016) "Why we need political economy," Policy Options, [1] Archived 2019-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bertholet, Auguste (2020-05-27). "The intellectual origins of Mirabeau". History of European Ideas. 47: 91–96. doi:10.1080/01916599.2020.1763745. ISSN 0191-6599. S2CID 219747599.

- ^ Bertholet, Auguste; Kapossy, Béla (2023). La Physiocratie et la Suisse (PDF) (in French). Geneva: Slatkine. ISBN 9782051029391.

- ^ "What is Political Economy?". Political Economy, Athabasca University. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-06.

- ^ Weingast, Barry R., and Donald Wittman, ed., 2008. The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy. Oxford UP. Description Archived 2013-01-25 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ At JEL: P as in JEL Classification Codes Guide Archived 2013-11-18 at the Wayback Machine, drilled to at each economic-system link.

For example:

• Brandt, Loren, and Thomas G. Rawski (2008). "Chinese economic reforms," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

• Helsley, Robert W. (2008). "urban political economy," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine - ^ At JEL: F5 as drilled to in JEL Classification Codes Guide Archived 2013-11-18 at the Wayback Machine.

For example:

• Gilpin, Robert (2001), Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order, Princeton. Description Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine and ch. 1, " The New Global Economic Order" link. Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

• Mitra, Devashish (2008). "trade policy, political economy of," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine - ^ At JEL: D72 and JEL: D74 Archived 2017-11-05 at the Wayback Machine with context for its usage in JEL Classification Codes Guide Archived 2013-11-18 at the Wayback Machine, drilled to at JEL: D7.

- ^ • Tullock, Gordon ([1987] 2008). "public choice," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Abstract Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine.

• Arrow, Kenneth J. (1963). Social Choice and Individual Values, 2nd ed., ch. VIII Archived 2013-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, sect. 2, The Social Decision Process, pp. 106–08. - ^ Lohmann, Susanne (2008). "rational choice and political science," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ • Shubik, Martin (1981). "Game Theory Models and Methods in Political Economy," in K. Arrow and M. Intriligator, ed., Handbook of Mathematical Economics, Elsevier, v. 1, pp. 285[dead link]–330.

• _____ (1984). A Game-Theoretic Approach to Political Economy. MIT Press. Description Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine and review extract.

• _____ (1999). Political Economy, Oligopoly and Experimental Games: The Selected Essays of Martin Shubik, v. 1, Edward Elgar. Description Archived 2012-05-24 at the Wayback Machine and contents of Part I Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, Political Economy.

• Peter C. Ordeshook (1990). "The Emerging Discipline of Political Economy," ch. 1 in Perspectives on Positive Political Economy, Cambridge, pp. 9–30. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

• _____ (1986). Game Theory and Political Theory, Cambridge. Description Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and preview. - ^ Alt, James E.; Shepsle, Kenneth (eds.) (1990), Perspectives on Positive Political Economy (Cambridge [UK]; New York: Cambridge University Press). Description and content links Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rose, N. L. (2001). "Regulation, Political Economy of," International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, pp. 12967–12970. Abstract.

- ^ Krueger, Anne O. (1974). "The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society," American Economic Review, 64(3), pp. 291–303.

- ^ • Bose, Niloy. "corruption and economic growth," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, 2nd Edition, 2010. Abstract. Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

• Rose-Ackerman, Susan (2008). "bribery," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine - ^ • Becker, Gary S. (1983). "A Theory of Competition among Pressure Groups for Political Influence," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(3), pp. 371–400. Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

• Weingast, Barry R., Kenneth A. Shepsle, and Christopher Johnsen (1981). "The Political Economy of Benefits and Costs: A Neoclassical Approach to Distributive Politics," Journal of Political Economy, 89(4), pp. 642–664. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

• Breyer, Friedrich (1994). "The Political Economy of Intergenerational Redistribution," European Journal of Political Economy, 10(1), pp. 61–84. Abstract.

• Williamson, Oliver E. (1995). "The Politics and Economics of Redistribution and Inefficiency," Greek Economic Review, December, 17, pp. 115–136, reprinted in Williamson (1996), The Mechanisms of Governance, Oxford University Press, ch. 8 Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 195–218.

• Krusell, Per, and José-Víctor Ríos-Rull (1999). "On the Size of U.S. Government: Political Economy in the Neoclassical Growth Model," American Economic Review, 89(5), pp. 1156–1181.

• Galasso, Vincenzo, and Paola Profeta (2002). "The Political Economy of Social Security: A Survey," European Journal of Political Economy, 18(1), pp. 1–29.[permanent dead link] - ^ • Drazen, Allan (2008). "Political business cycles," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2010-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

• Nordhaus, William D. (1989). "Alternative Approaches to the Political Business Cycle," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2), pp. 1 Archived 2020-04-01 at the Wayback Machine–68. - ^ • Buchanan, James M. (2008). "public debt," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

• Alesina, Alberto, and Roberto Perotti (1995). "The Political Economy of Budget Deficits," IMF Staff Papers, 42(1), pp. 1–31. - ^ Written at Moscow. Political Economy: A Textbook issued by the Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R [Political Economy: A Textbook issued by the Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R] (in Russian) (1st ed.). Marxists Internet Archive: Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R (published 2014). 1954.

- ^ • Timothy, Besley (2007). Principled Agents?: The Political Economy of Good Government, Oxford. Description. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

• _____ and Torsten Persson (2008). "political institutions, economic approaches to," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

• North, Douglass C. (1986). "The New Institutional Economics," Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 142(1), pp. 230–237.

• _____ (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, in the Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions series. Cambridge. Description Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

• Ostrom, Elinor (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press. Description Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and preview links. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 9780521405997.

• _____ (2010). "Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems," American Economic Review, 100(3), pp. 641–672 Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ Dixit, Avinash (1996). The Making of Economic Policy: A Transaction Cost Politics Perspective. MIT Press. Description Archived 2017-11-17 at the Wayback Machine and chapter-preview links. Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine Review-excerpt link Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Beck, Thorsten et al. (2001). "New Tools in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions," World Bank Economic Review,15(1), pp. 165–176.

- ^ Bolton, Patrick, and Gérard Roland (1997). "The Breakup of Nations: A Political Economy Analysis," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), pp. 1057–1090. Archived 2012-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alesina, Alberto, and Roberto Perotti (1994). "The Political Economy of Growth: A Critical Survey of the Recent Literature," World Bank Economic Review, 8(3), pp. 351–371. Archived 2011-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Keefer, Philip (2004). "What Does Political Economy Tell Us about Economic Development and Vice Versa?" Annual Review of Political Science, 7, pp. 247–272. PDF. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Perotti, Enrico (2014). "The Political Economy of Finance", in "Capitalism and Society" Vol. 9, No. 1, Article 1 [2]

- ^ "Chang, H. J. (2002). Breaking the Mould – An Institutionalist Political Economy Alternative to the Neo-Liberal Theory of the Market and State", in "Cambridge Journal of Economics", 26(5), [3] Archived 2019-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson (2006). "Economic Backwardness in Political Perspective," American Political Science Review, 100(1), pp. 115–131 Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ • Mukand, Sharun W. (2008). "policy reform, political economy of," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

• Sturzenegger, Federico, and Mariano Tommasi (1998). The Polítical Economy of Reform, MIT Press. Description Archived 2012-10-11 at the Wayback Machine and chapter-preview links. - ^ • Roland, Gérard (2002), "The Political Economy of Transition," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(1), pp. 29–50. Archived 2021-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

• _____ (2000). Transition and Economics: Politics, Markets, and Firms, MIT Press. Description Archived 2018-04-16 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

• Manor, James (1999). The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization, The World Bank. ISBN 9780821344705. Description.[permanent dead link] - ^ Alesina, Alberto F. (2007:3) "Political Economy," NBER Reporter, pp. 1–5 Archived 2011-06-11 at the Wayback Machine. Abstract-linked-footnotes version.

- ^ Drazen, Allan (2000). Political Economy in Macroeconomics, Princeton. Description Archived 2010-10-22 at the Wayback Machine & ch. 1-preview link. Archived 2010-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, and review extract.

- ^ • Dietz, Simon, Jonathan Michie, and Christine Oughton (2011). Political Economy of the Environment An Interdisciplinary Approach, Routledge. Description Archived 2013-06-23 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2013-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

• Banzhaf, H. Spencer, ed. (2012). The Political Economy of Environmental Justice Stanford U.P. Description and contents links. Archived 2013-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

• Gleeson, Brendan, and Nicholas Low (1998). Justice, Society and Nature An Exploration of Political Ecology, Routledge. Description Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

• John S. Dryzek, 2000. Rational Ecology: Environment and Political Economy, Blackburn Press. B&N description. Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

• Barry, John 2001. "Justice, Nature and Political Economy," Economy and Society, 30(3), pp. 381–394. Archived 2017-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

• Boyce, James K. (2002). The Political Economy of the Environment, Edward Elgar. Description. Archived 2013-05-22 at the Wayback Machine - ^ •

Zajac, Edward E. (1996). Political Economy of Fairness, MIT Press Description Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine and chapter-preview links.

• Thurow, Lester C. (1980). The Zero-sum Society: Distribution and the Possibilities For Economic Change, Penguin. Description Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine - ^ • Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini (2000). Political Economics: Explaining Economic Policy, MIT Press. Review extract, description and chapter-preview links. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

• Laffont, Jean-Jacques (2000). Incentives and Political Economy, Oxford. Description. Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

• Acemoglu, Daron (2003). "Why Not a Political Coase Theorem? Social Conflict, Commitment, and Politics," Journal of Comparative Economics, 31(4), pp. 620–652. Archived 2012-03-04 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Persson, Torsten, and Guido Tabellini (2003). The Economic Effects Of Constitutions, Munich Lectures in Economics. MIT Press. Description Archived 2013-01-15 at the Wayback Machine and preview Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine, and review extract.

- ^ Mayer, Charles S. (1987). In Search of Stability: Explorations in Historical Political Economy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 3–6. Description Archived 2013-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and scrollable preview. Archived 2023-04-30 at the Wayback Machine Cambridge.

- ^ cf: Baker, David (2006). "The political economy of fascism: Myth or reality, or myth and reality?" Archived 2011-06-23 at the Wayback Machine, New Political Economy, 11(2), pp. 227–250.

- ^ Brown, Chris (July 1999). "Susan Strange—a critical appreciation". Review of International Studies. 25 (3): 531–535. doi:10.1017/S0260210599005318. ISSN 1469-9044.

- ^ Cohen, Benjamin J. "The transatlantic divide: Why are American and British IPE so different?", Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 14, No. 2, May 2007.

- ^ McCoy, Drew R. "The Elusive Republic: Political Economy in Jeffersonian America", Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina.

- ^ Kennedy, David (2013). "Law and the Political Economy of the World" (PDF). Leiden Journal of International Law. 26: 7–48. doi:10.1017/S0922156512000635. S2CID 153363066. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ^ Haskell, John D. (2015). Research Handbook on Political Economy and Law. Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1781005347.

- ^ Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0674430006

- ^ "About Political Economy | Department of Political Economy | King's College London". Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ "Why Political Economy?". SPERI. 2012-11-05. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ^ "Home". The Political Economy UK Group. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-04.

- ^ "political economy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-06-15.

- ^ Hirth, Kenneth G. 1996. Political Economy and Archaeology: Perspectives on Exchange and Production. Journal of Archaeological Research, 4(3):203–239.

- ^ May, Robert M.; Levin, Simon A.; Sugihara, George (February 21, 2008). "Ecology for bankers". Nature. 451 (7181): 893–895. doi:10.1038/451893a. PMID 18288170.

References

[edit]- Baran, Paul A. (1957). The Political Economy of Growth. Monthly Review Press, New York. Review extrract. Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Commons, John R. (1934 [1986]). Institutional Economics: Its Place in Political Economy, Macmillan. Description Archived 2011-05-10 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- David, F., "Utopia and the Critique of Political Economy." Journal of Australian Political Economy, Australian Political Economy Movement, 1 Jan. 2017

- Komls, John (2023). Foundations of Real-World Economics; What Every Economics Student Needs To Know (3rd edition) Routledge.

- Leroux, Robert (2011), Political Economy and Liberalism in France : The Contributions of Frédéric Bastiat, London, Routledge.

- Maggi, Giovanni, and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare (2007). "A Political-Economy Theory of Trade Agreements," American Economic Review, 97(4), pp. 1374–1406.

- O'Hara, Phillip Anthony, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Political Economy, 2 v. Routledge. 2003 review links.

- Pressman, Steven, Interactions in Political Economy: Malvern After Ten Years Routledge, 1996

- Rausser, Gordon, Swinnen, Johan, and Zusman, Pinhas (2011). Political Power and Economic Policy. Cambridge University Press.

- Winch, Donald (1996). Riches and Poverty : An Intellectual History of Political Economy in Britain, 1750–1834 Cambridge University Press.

External links

[edit]- NBER (U.S.) "Political Economy" working-paper abstract links.

- VoxEU.org (Europe) "Politics and economics" article links.

- An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Oeconomy, by James Steuart (1712-1780), two volumes.

- Harriet Martineau 1802-1876, a writer on political economy, some books at Project Gutenberg

KSF

KSF