Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

The ruins of Göbekli Tepe, c. 9,000 BCE The ruins of Göbekli Tepe, c. 9,000 BCE | |

| Geographical range | Near East |

|---|---|

| Period | Pre-Pottery Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 10,000 – c. 8,800 BCE[1] |

| Type site | Jericho |

| Preceded by | Khiamian, Harifian |

| Followed by | Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, Neolithic Greece, Faiyum A culture |

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, in early Levantine and Anatolian Neolithic culture, dating to c. 12,000 – c. 10,800 years ago, that is, 10,000–8800 BCE.[1][2][3] Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and Upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent.

The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud-brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.[4]

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho, State of Palestine. During this time, pottery was not yet in use. They precede the ceramic Neolithic Yarmukian culture. PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipalaeolithic Near East.

Settlements

[edit]

PPNA archaeological sites are much larger than those of the preceding Natufian hunter-gatherer culture, and contain traces of communal structures, such as the famous Tower of Jericho. PPNA settlements are characterized by round, semi-subterranean houses with stone foundations and terrazzo-floors.[7] The upper walls were constructed of unbaked clay mudbricks with plano-convex cross-sections. The hearths were small and covered with cobbles. Heated rocks were used in cooking, which led to an accumulation of fire-cracked rock in the buildings, and almost every settlement contained storage bins made of either stones or mud-brick.

As of 2013, Gesher, modern Israel, became the earliest known of all known Neolithic sites (PPNA), with a calibrated Carbon 14 date of 10,459 BCE ± 348 years, analysis suggesting that it may have been the starting point of a Neolithic Revolution.[8] A contemporary site is Mureybet in modern Syria.[8]

One of the most notable PPNA settlements is Jericho, thought to be the world's first town (c. 9,000 BCE).[9] The PPNA town contained a population of up to 2–3000 people and was protected by a massive stone wall and tower. There is much debate over the function of the wall, for there is no evidence of any serious warfare at this time.[10] One possibility is the wall was built to protect the salt resources of Jericho.[11] It has also been proposed that the tower caught the shadow of the largest nearby mountain on summer solstice in order to create a sense of power in support of whatever hierarchy ruled the town's inhabitants.[12]

-

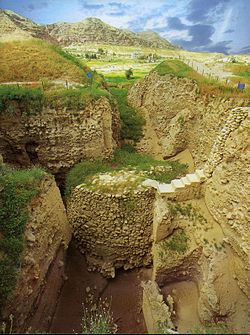

The Tower of Jericho was built at the end of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A, c. 8000 BCE.

-

Human plastered head from the Levant during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic phases.

Burial practices

[edit]PPNA cultures are unique for their burial practices, and Kenyon (who excavated the PPNA level of Jericho) characterized them as "living with their dead". Kenyon found no fewer than 279 burials, below floors, under household foundations, and in between walls.[16] In the PPNB period, skulls were often dug up and reburied, or mottled with clay and (presumably) displayed.

Lithics

[edit]The lithic industry is based on blades struck from regular cores. Sickle-blades and arrowheads continue traditions from the late Natufian culture, transverse-blow axes and polished adzes appear for the first time.[17]

Crop cultivation and granaries

[edit]

Sedentism of this time allowed for the cultivation of local grains, such as barley and wild oats, and for storage in granaries. Sites such as Dhra′ and Jericho retained a hunting lifestyle until the PPNB period, but granaries allowed for year-round occupation.[19]

This period of cultivation is considered "pre-domestication", but may have begun to develop plant species into the domesticated forms they are today. Deliberate, extended-period storage was made possible by the use of "suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents". This practice "precedes the emergence of domestication and large-scale sedentary communities by at least 1,000 years".[2]

Granaries are positioned in places between other buildings early on c. 11,500 BP, however, beginning around 10,500 BP, they were moved inside houses, and by 9,500 BP, storage occurred in special rooms.[2] This change might reflect changing systems of ownership and property as granaries shifted from communal use and ownership to become under the control of households or individuals.[2]

It has been observed of these granaries that their "sophisticated storage systems with subfloor ventilation are a precocious development that precedes the emergence of almost all of the other elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic package—domestication, large scale sedentary communities, and the entrenchment of some degree of social differentiation". Moreover, "building granaries may [...] have been the most important feature in increasing sedentism that required active community participation in new life-ways".[2]

Regional variants

[edit]

With more sites becoming known, archaeologists have defined a number of regional variants of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A:

- (Aswadian) in the Damascus Basin, defined by finds from Tell Aswad IA; typical: bipolar cores, big sickle blades, Aswad points. The 'Aswadian' variant recently was abolished by the work of Danielle Stordeur in her initial report from further investigations in 2001–2006. The PPNB horizon was moved back at this site, to around 10,700 BP.[20]

- Mureybetian in the Northern Levant, defined by the finds from Mureybet IIIA, IIIB, typical: Helwan points, sickle-blades with base amenagée or short stem and terminal retouch.[21] Other sites include Sheyk Hasan and Jerf el Ahmar.

- Sites in "Upper Mesopotamia" include Çayönü and Göbekli Tepe, with the latter possibly being the oldest ritual complex yet discovered.[22]

- Sites in central Anatolia that include the 'mother city' Çatalhöyük and the smaller, but older site, rivaling even Jericho in age, Aşıklı Höyük.

- Sultanian in the Jordan River valley and southern Levant, with the type site of Jericho. Other sites include Netiv HaGdud, El-Khiam, Hatoula, and Nahal Oren.

Relative chronology

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Chazan, Michael (2017). World Prehistory and Archaeology: Pathways Through Time. Routledge. p. 197. ISBN 978-1351802895.

- ^ a b c d e Kuijt, I.; Finlayson, B. (June 2009). "Evidence for food storage and predomestication granaries 11,000 years ago in the Jordan Valley". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (27): 10966–10970. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10610966K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812764106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2700141. PMID 19549877.

- ^ Ozkaya, Vecihi (June 2009). "Körtik Tepe, a new Pre-Pottery Neolithic A site in south-eastern Anatolia". Antiquitey Journal, Volume 83, Issue 320.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2006). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000–5,000 BC (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7.

- ^ Zalloua, Pierre A.; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth (6 January 2017). "Mapping Post-Glacial expansions: The Peopling of Southwest Asia". Scientific Reports. 7: 40338. Bibcode:2017NatSR...740338P. doi:10.1038/srep40338. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5216412. PMID 28059138.

- ^ Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): Appendix S1. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- ^ Fujii, Sumio (25 March 2024). "Settlement Pattern and Periodization of the Jordanian Badia Early PPNB: A Fresh Approach to the PPNA/PPNB Transition Issue in the Southern Levant". Paléorient. Revue pluridisciplinaire de préhistoire et de protohistoire de l'Asie du Sud-Ouest et de l'Asie centrale. 49–2 (49–2): 109–134. doi:10.4000/paleorient.3582. ISSN 0153-9345.

- ^ a b Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- ^ Gates, Charles (2003). "Near Eastern, Egyptian, and Aegean Cities", Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-415-01895-1.

Jericho, in the Jordan River Valley in the West Bank, inhabited from c. 9000 BC to the present day, offers important evidence for the earliest permanent settlements in the Near East.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2006). After the ice : a global human history, 20,000–5,000 BC (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7.

- ^ "Jericho", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Liran, Roy; Barkai, Ran (March 2011). "Casting a shadow on Neolithic Jericho". Antiquitey Journal, Volume 85, Issue 327.

- ^ Chacon, Richard J.; Mendoza, Rubén G. (2017). Feast, Famine or Fighting?: Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity. Springer. p. 120. ISBN 978-3319484020.

- ^ Schmidt, Klaus (2015). Premier temple. Göbekli tepe (Le): Göbelki Tepe (in French). CNRS Editions. p. 291. ISBN 978-2271081872.

- ^ Collins, Andrew (2014). Gobekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods: The Temple of the Watchers and the Discovery of Eden. Simon and Schuster. p. 66. ISBN 978-1591438359.

- ^ Mithen, Steven (2006). After the ice : a global human history, 20,000–5,000 BC (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7.

- ^ Dietrich, Laura; Götting-Martin, Eva; Hertzog, Jasmine; Schmitt-Kopplin, Philippe; McGovern, Patrick E.; Hall, Gretchen R.; Petersen, W. Christian; Zarnkow, Martin; Hutzler, Mathias; Jacob, Fritz; Ullman, Christina; Notroff, Jens; Ulbrich, Marco; Flöter, Eckhard; Heeb, Julia (1 December 2020). "Investigating the function of Pre-Pottery Neolithic stone troughs from Göbekli Tepe – An integrated approach". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 34: 102618. Bibcode:2020JArSR..34j2618D. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102618. ISSN 2352-409X.

- ^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.4523. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734. S2CID 13350469.

- ^ Qu, Yating; Zhu, Junxiao; Yang, Han; Zhou, Longlong (17 May 2023). "Food, cooking and potteries in the Neolithic Mijiaya site, Guanzhong area, North China, revealed by multidisciplinary approach". Heritage Science. 11 (1): 107. doi:10.1186/s40494-023-00950-3. ISSN 2050-7445.

- ^ Stordeur, Daneille. "La Néolithisation du Proche-Orient". Archéorient Laboratory - Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée - Lyon (in French). CNRS - French National Centre for Scientific Research. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Young, Theodore Cuyler Jr; Smith, Philip E. L.; Mortensen, Peder (1983). The hilly flanks and beyond: essays on the prehistory of Southwestern Asia presented to Robert J. Braidwood, November l5, l982. Studies in ancient Oriental civilization (in French). Chicago (Ill.): Oriental institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-918986-37-5.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (November 2008). "Göbekli Tepe: The World's First Temple?". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2009. Directrice de la mission permanente El Kowm-Mureybet (Syrie) du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères – Recherches sur le Levant central/sud : Premiers résultats.

Further reading

[edit]- J. Cauvin, Naissance des divinités, Naissance de l’agriculture. La révolution des symboles au Néolithique (CNRS 1994). Translation (T. Watkins) The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture (Cambridge 2000).

- O. Bar-Yosef, The PPNA in the Levant – an overview. Paléorient 15/1, 1989, 57–63.

KSF

KSF

![The Urfa Man c. 9000 BCE.[13][14][15] Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Urfa_man.jpg/120px-Urfa_man.jpg)