Pueblo II Period

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

| Ancestral Puebloan periods |

|---|

|

|

Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era 7000–1500 BCE |

|

Early Basketmaker II Era 1500 BCE–50 CE |

|

Late Basketmaker II Era 50–500 |

|

Basketmaker III Era 500–750 |

|

Pueblo I Period 750–900 |

|

Pueblo II Period 900–1150 |

|

Pueblo III Period 1150–1350 |

|

Pueblo IV Period 1350–1600 |

|

Pueblo V Period 1600–present |

The Pueblo II Period (AD 900 to AD 1150) was the second pueblo period of the Ancestral Puebloans of the Four Corners region of the American southwest. During this period people lived in dwellings made of stone and mortar, enjoyed communal activities in kivas, built towers and dams for water conservation, and implemented milling bins for processing maize. Communities with low-yield farms traded pottery with other settlements for maize.

The Pueblo II Period (Pecos Classification) is roughly similar[how?] to the second half of the "Developmental Pueblo Period" (AD 750 to AD 1100). It is preceded by the Pueblo I Period, and is followed by the Pueblo III Period.

Architecture

[edit]Villages were larger and had more community buildings than in the Pueblo I Period. Structures were generally made of stone masonry. By AD 1075, double-coursed masonry was sometimes used, which allowed for second story construction.[1][2][3] Homes made of stone were more sturdy and fire-proof than the materials used previously. The grouping of the pueblos were called "unit pueblos".[4][5] Some pueblo sites used a standard plan of front and back pairs of rooms which formed a common cluster of 12 rooms; The rear rooms were used for storage and the front rooms used as living areas.[6]

Round-shaped, below ground and standardized kivas were used for ceremonial purposes. Large kivas, called great kivas, were built for community celebrations and were sometimes as large as 55 feet (17 m) in diameter.[1][2][3] Towers, up to 15 feet (4.6 m) tall, were built with housing clusters, with underground access to a kiva or as look-out posts. Trash mounds were generally placed south of the village.[3]

Communities

[edit]- Four Corners Region. Due to the dry conditions in the southwest and growing population, communities responded by branching out and establishing new villages and farmland; More than 10,000 sites were established in a 150-year period. During the Pueblo II Period, nearly every spot in the southwest that would support farming not in a flood plain was used for agriculture. Hunter-gatherer artifacts are not found much in the Four Corners region during this period. It is likely that they hunter-gatherer tribes were either forced to seek foraging land in other areas or they assimilated themselves into the Pueblo agricultural lifestyle.[7]

- Mesa Verde. In the Mesa Verde National Park region, contiguous rows of rooms formed E-, U- and L-shaped buildings, and were often formed around a plaza.[3]

- Chaco Canyon. Elaborate, great houses from the Pueblo I Period continued to be built at Chaco Canyon into the 12th century. The structures were much larger than previous dwellings. The multi-storied buildings had high ceilings, rooms with three or four times the space of domestic dwellings and elaborate kivas, such as great, tower and above ground kivas.[8]

- Chimney Rock. Outlier of the Chaco Canyon regional system.

-

Agate House at Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona

Culture and religion

[edit]- Religion. Community based activities emerged, including ceremonial rituals in great kivas.[3]

- Wall art. Petroglyphs, which appeared in the Petrified Forest National Park during the Basketmaker periods, were made during the Pueblo II and III Periods throughout the Little Colorado River basin. Some of the petroglyphs were solar markers that marked seasonal passage of time between seasonal equinoxes and solstices based upon the suns position in the sky.[9][10]

Agriculture

[edit]Production and use of water conservation dams and reservoirs were also a community-based activities. Reservoirs might reach 90 feet (27 m) in diameter by 12 feet (3.7 m) deep, such as the reservoir near Far View House in Mesa Verde National Park. Terraced, silt-retaining check dams were created on sloping drainage areas where melting snow or rain water ran downhill through the terraced dams. The dams retained moisture and silt and effectively managed runoff to lower terraces which made an ideal scenario for southwestern agriculture.[3][4]

The population grew during this period, requiring greater amounts of food for the villages.[3] To increase their yield, there was experimentation to cultivate larger corn cobs, including the Mexican or southern Arizona maize blanco and oñaveno, and locally produced hybrids. They supplemented their diet with hunting and wild plants found on small patches of land unsuitable for farming, but as the land became over-populated, wild food and game became scarce.[11]

The optimal southwestern farming locations were adjacent to springs, seeps or marshes. Early in the Pueblo II period, the most desirable spots had been taken and, presumably young, families searched out open land to farm, hoping that precipitation would be sufficient to support their crops.[12] There were periods of time of seasonal hunger and drought when people moved away from their villages and returned "following the rains," stories told by elders of pueblo communities. Evidence of near starvation as children are evident in the interrupted growth lines in their bones and enamel hypoplasias in their teeth.[13]

The number rooms for work areas and storage increased during this period. Often the rooms were in the residential buildings, in some cases there were deep pit-houses. Nearly 25% of the rooms were used for grinding corn on metates and storing the grain in mealing bins.[14] The mealing bins were designed for grinding areas, where the bins were set alongside one another during a communal effort to grind corn using metates and manos.[4]

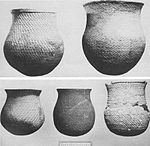

Pottery

[edit]Common pottery include corrugated gray ware pottery and decorated black-on-white pottery.[1] Corrugated pottery was made from coils of clay wound into the desired shape and the clay is pinched, which created the corrugated texture.[4] In addition to the common gray were used for cooking and storage, pottery from this period included bowls, jars with lids, mugs, ladles, canteens, pitchers, and effigy pots in bird and animals shapes.[4]

Pottery was used in trade for food in low-productive farming areas. This helped supplement the diets of people who needed to barter for food – and allowed those with very productive lands to focus on farming. For instance, Chaco Canyon area produced large amounts of surplus food which was traded for pottery.[12]

-

Mesa Verde Pueblo II corrugated jars Source: National Park Service

-

Mesa Verde Pueblo II Mancos Black-on-White jar and ladle Source: National Park Service

-

Mesa Verde Pueblo II Mancos Black-on-White Pottery Source: National Park Service

-

Anasazi bowl (trade ware) dating from 900–1100 excavated at Chaco Culture National Historical Park

Other material goods

[edit]Material goods changed little from the previous periods, such as:[2][3][4][15]

- stone tools, such as axes, hammerstones, pecking stones, knives and scrapers

- manos and metates to grind corn and plants

- bone awls, scrapers, flakers, projectile points

- bow and arrows

- snares

- pottery

- digging sticks

- clothing made from cotton, yucca or hides

- hard cradle boards introduced in Pueblo I

- gaming pieces, pendants and beads

-

Mesa Verde Pueblo II manos Source: National Park Service

-

Sandal from 700 to 1100. Source: National Park Service

Cultural groups and periods

[edit]The cultural groups of this period include:[16]

- Ancestral Puebloans – southern Utah, southern Colorado, northern Arizona and northern and central New Mexico.

- Hohokam – southern Arizona.

- Mogollon – southeastern Arizona, southern New Mexico and northern Mexico.

- Patayan – western Arizona, California and Baja California.

Notable Pueblo II sites

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Pueblo Indian History. Archived 2011-10-08 at the Wayback Machine Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. Retrieved 10–9–2011.

- ^ a b c Lancaster, James A.; Pinkley, Jean M. Excavation at Site 16 of three Pueblo II Mesa-Top Ruins. Archeological Excavations in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. National Park Service. May 19, 2008. Retrieved 10–9–2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wenger, Gilbert R. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Mesa Verde Museum Association, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991 [1st edition 1980]. pp. 39–45. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Ancestral Puebloan Chronology (teaching aid). Mesa Verde National Park, National Park Service. Retrieved 10–16–2011.

- ^ Reed, Paul F. (2000) Foundations of Anasazi Culture: The Basketmaker Pueblo Transition. University of Utah Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-87480-656-9.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Pueblo Period. Chaco Culture National Historical Park, National Park Services. Retrieved 10–15–2011.

- ^ Ancient Farmers. Petrified Forest National Park, National Park Service. Retrieved 10–16–2011.

- ^ Petrified Forest National Park Celebrates the Summer Solstice. Petrified Forest National Park, National Park Service. Retrieved 10–16–2011.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 57, 61. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ a b Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 59, 61. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 59–60. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000) Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. University of New Mexico Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- ^ Gibbon, Guy E.; Ames, Kenneth M. (1998) Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 14, 408. ISBN 0-8153-0725-X.

KSF

KSF