Reel-to-reel audio tape recording

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

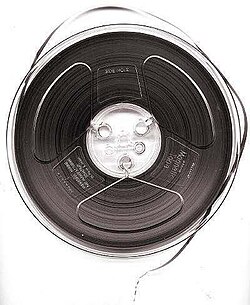

Reel-to-reel audio tape recording, also called open-reel recording, is magnetic tape audio recording in which the recording tape is spooled between reels. To prepare for use, the supply reel (or feed reel) containing the tape is placed on a spindle or hub. The end of the tape is manually pulled from the reel, threaded through mechanical guides and over a tape head assembly, and attached by friction to the hub of the second, initially empty takeup reel. Reel-to-reel systems use tape that is 1⁄4, 1⁄2, 1, or 2 inches (6.35, 12.70, 25.40, or 50.80 mm) wide, which normally moves at 3+3⁄4, 7+1⁄2, 15 or 30 inches per second (9.525, 19.05, 38.10 or 76.20 cm/s). Domestic consumer machines almost always used 1⁄4 inch (6.35 mm) or narrower tape and many offered slower speeds such as 1+7⁄8 inches per second (4.762 cm/s). All standard tape speeds are derived as a binary submultiple of 30 inches per second.

Reel-to-reel preceded the development of the compact cassette with tape 0.15 inches (3.8 mm) wide moving at 1+7⁄8 inches per second (4.8 cm/s). By writing the same audio signal across more tape, reel-to-reel systems give much greater fidelity at the cost of much larger tapes. In spite of the relative inconvenience and generally more expensive media, reel-to-reel systems developed in the early 1940s remained popular in audiophile settings into the 1980s and have re-established a specialist niche in the 21st century.

Studer, Stellavox, Tascam, and Denon produced reel-to-reel tape recorders into the 1990s, but as of 2017[update], only Mechlabor[1] continues to manufacture analog reel-to-reel recorders. As of 2020[update], there were two companies manufacturing magnetic recording tape: ATR Services of York, Pennsylvania, and Recording the Masters in Avranches, France.[2]

Reel-to-reel tape was used in early tape drives for data storage on mainframe computers and in video tape recorders. Magnetic tape was also used to record data signals from analytical instruments, beginning with the hydrogen bomb testing of the early 1950s.

History

[edit]

The reel-to-reel format was used in the first magnetic recording systems, wire recording and then in the earliest tape recorders, including the pioneering German-British Blattnerphone (1928) machines which used steel tape,[3] and the German Magnetophon machines of the 1930s. Originally, this format had no name, since all forms of magnetic tape recorders used it. The name arose only with the need to distinguish it from the several kinds of tape cartridges or cassettes such as the Fidelipac endless loop cartridge developed for radio station commercials and spot announcements in 1954, the RCA tape cartridge, developed in 1958 for home use, and the Compact Cassette developed by Philips in 1963, originally for dictation.

The earliest machines produced distortion during the recording process which German engineers significantly reduced during the Nazi Germany era by applying a DC bias signal to the tape. In 1939, one machine was found to make consistently better recordings than other ostensibly identical models, and when it was taken apart a minor flaw was noticed. Instead of DC, it was introducing an AC bias signal to the tape,[citation needed] and this was quickly adapted to new models using a high-frequency AC bias that has remained a part of audio tape recording to this day. The quality was so greatly improved that recordings surpassed the quality of most radio transmitters, and such recordings were used by Adolf Hitler to make broadcasts that appeared to be live while he was safely away in another city.

American audio engineer Jack Mullin was a member of the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War II. His unit was assigned to investigate German radio and electronics activities, and in the course of his duties, a British Army counterpart mentioned the Magnetophons being used by the allied radio station in Bad Nauheim near Frankfurt. He acquired two Magnetophon recorders and 50 reels of I.G. Farben recording tape and shipped them home. Over the next two years, he worked to develop the machines for commercial use, hoping to interest the Hollywood film studios in using magnetic tape for movie soundtrack recording.

Mullin gave a demonstration of his recorders at MGM Studios in Hollywood in 1947, which led to a meeting with Bing Crosby, who immediately saw the potential of Mullin's recorders to pre-record his radio shows. Crosby invested $50,000 in a local electronics company, Ampex, to enable Mullin to develop a commercial production model of the tape recorder. Using Mullin's tape recorders, and with Mullin as his chief engineer, Crosby became the first American performer to master commercial recordings on tape and the first to regularly pre-record his radio programs on the medium.

Ampex and Mullin subsequently developed commercial stereo and multitrack audio recorders, based on the system originally invented by Ross Snyder of Ampex Corporation for their high-speed scientific instrument data recorders. Les Paul had been given one of the first Ampex Model 200A tape decks by Crosby in 1948, and ten years later ordered one of the first Ampex eight-track Sel Sync machines for multitracking.[a] Ampex engineers, who included Ray Dolby on their staff at the time, went on to develop the first practical videotape recorders in the early 1950s to pre-record Crosby's TV shows.

Inexpensive reel-to-reel tape recorders were widely used for voice recording in the home and in schools, along with dedicated models expressly made for business dictation. When the Philips compact cassette was introduced in 1963 it gradually took over and cassettes eventually displaced reel-to-reel recorders for consumer use. However, the narrow tracks and slow recording speeds used in cassettes compromised fidelity and so Ampex produced pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes for consumers of popular and classical music from the mid-1950s to the mid-'70s, as did Columbia House from 1960 to 1984.

Following the example set by Bing Crosby, large reel-to-reel tape recorders rapidly became the main recording format used by audiophiles and professional recording studios until the late 1980s when digital audio recording techniques began to allow the use of other types of media (such as Digital Audio Tape (DAT) cassettes and hard disks).

Even today, some artists of all genres prefer analog tape, claiming it is more musical or natural sounding than digital processes, despite its inaccuracies. Due to harmonic distortion, bass can thicken up, creating a fuller-sounding mix. High-end frequencies can be slightly compressed. Tape saturation is a unique form of distortion that many artists find satisfying. Though with modern technology, these forms of distortion can be simulated digitally,[4] it is not uncommon for some artists to record directly onto digital equipment and then re-record the tracks to analog reel tape or vice versa.

The great practical advantage of tape for studios was twofold: it allowed a performance to be recorded without the 30-minute time limitation of a phonograph disc, and it permitted a recorded performance to be edited or erased and re-recorded again and again on the same piece of media without any waste. For the first time, audio could be manipulated as a physical entity, and the recording process was greatly economized by eliminating the requirement for a highly trained disc-cutting engineer to be present at every recording session. Once a tape machine was installed and calibrated, there was no need for any attendant engineering, other than to spool or replace the tape being used on it. Daily maintenance consisted of cleaning and occasionally demagnetizing the heads and guides.

Tape editing is performed simply by cutting the tape at the required point and rejoining it to another section of tape using adhesive tape, or sometimes glue; it is called a splice. The adhesive tape used in splicing has to be very thin to avoid impeding the tape's motion, and the adhesive is carefully formulated to avoid leaving a sticky residue on the tape or deck. Butt splices (cut at exactly 90 degrees to the tape travel) are used for fast edits from one sound to another, though preferably, the splice is made at a much lower angle across the tape so that any transitional noise introduced by the cut is spread across a few milliseconds of the recording. The low-angle splice also helps to glide the tape more smoothly through the machine and push any loose dirt or debris to the side of the tape path, instead of accumulating in the splice joint. A side-effect of cutting the tape at an angle is that on stereo tapes the edit occurs on one channel a split-second before the other. Long, angled splices can also be used to create a perceptible dissolve from one sound to the next; periodic segments can induce rhythmic or pulsing effects.[5] The use of reels to supply and collect the tape makes it easy for editors to manually move the tape back and forth across the heads to find the exact point they wish to edit. Tape to be spliced is clamped in a splicing block attached to the deck near the heads to hold the tape accurately while the edit is made. The Editall was a long-in-production splicing block, named for its inventor Joe Tall, a tape editor at CBS.[6]

The performance of tape recording is greatly affected by the width of the tracks and the speed of the tape. The wider and faster the better, but of course this uses more tape. These factors lead directly to improved frequency response, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR or S/N), and high-frequency distortion figures. Tape can accommodate multiple parallel tracks, allowing not just stereo recordings, but multitrack recordings too. This gives the producer of the final edit much greater flexibility, allowing a performance to be remixed long after the performance was originally recorded. This innovation was a great driving force behind the explosion of popular music in the late 1950s and 1960s.[citation needed]

It was discovered that special effects were possible, such as phasing and flanging, delays and echo by re-directing the signal through one or more additional tape machines, while recording the composite result to another. These innovations appeared on pop recordings shortly after multi-tracking recorders were introduced, although, Les Paul had been using tape echo and speed-manipulation effects on his single-track recordings from the 1940s and '50s.

For home use, simpler reel-to-reel recorders were available, and a number of track formats and tape speeds were standardized to permit interoperability and prerecorded music.

Reel-to-reel tape editing also gained cult status when many used this technique on hit singles in the 1980s.

In the former USSR, reel-to-reel tape recorders were widely used at home until the fall of communism in 1991. It was the only source of quality sound used for the distribution of Western music as well as underground local artists.[citation needed]

There has recently been a revival of reel-to-reel, with quite a few companies restoring vintage units and some manufacturing new tape. In 2018, the first new reel-to-reel tape player in over 20 years was released.[7]

Pre-recorded tapes

[edit]

The first prerecorded reel-to-reel tapes were introduced in the United States in 1949; the catalog contained fewer than ten titles with no popular artists. In 1952, EMI started selling pre-recorded tapes in Great Britain. The tapes were two-sided and mono (2 tracks) and were duplicated in real time on modified EMI BTR2 recorders. RCA Victor joined the reel-to-reel business in 1954. In 1955, EMI released 2-track stereosonic tapes, although the catalog took longer to be published. Since these EMI tapes were much more expensive than a vinyl LP record, sales were poor; still, EMI released over 300 stereosonic titles. Then they introduced their Twin Packs, which contained the equivalent of two LP albums but played at 3.75 ips.[citation needed]

The heyday of prerecorded reel-to-reel tapes was the mid-1960s, but after the introduction of less complicated cassette tapes and 8-track tapes, the number of albums released on prerecorded reel-to-reel tape dropped dramatically despite their superior sound quality. By the late 1960s, their retail prices were considerably higher than competing formats, and musical genres were limited to ones most likely to appeal to well-heeled audiophiles willing to contend with the cumbersome threading of open-reel tape. The introduction of the Dolby noise-reduction system narrowed the performance gap between cassettes and reel-to-reel, and by 1976 prerecorded reel-to-reel offerings had almost completely disappeared, even from record stores and audio equipment shops. Columbia House advertisements in 1978 showed that only one-third of new titles were available on reel-to-reel; they continued to offer a select number of new releases in the format until 1984.[citation needed]

Sales were very low and specialized during the 1980s. Audiophile reel tapes were made under license by Barclay-Crocker between 1977 and 1986. Licensors included Philips, Deutsche Grammophon, Argo, Vanguard, Musical Heritage Society, and L'Oiseau Lyre. Barclay-Crocker tapes were all Dolby encoded and some titles were also available in the dbx format. The majority of the catalog contained classical recordings, with a few jazz and movie soundtrack albums. Barclay-Crocker tapes were duplicated on modified Ampex 440 machines at four times the playback speed, unlike popular reel tapes which were duplicated at 16 times the playback speed.

Pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes are also available once again, albeit somewhat expensively as a very high-quality audiophile product, through "The Tape Project", as well as several other independent studios and record labels.[8] Since 2007, The Tape Project has released their own albums, as well as previously-released albums under license from other labels, on open-reel tape.[9][non-primary source needed] The German label Analogue Audio Association has also re-released albums on open-reel tape to the high-end audiophile market.[10][non-primary source needed]

Technology

[edit]Reel-to-reel tape recording is done with electro-magnetism, electronic audio circuitry, and electro-mechanical drive systems.[11][12]

Electromagnetic recording and playback

[edit]Magnetic-tape tape recorders record sound by magnetizing particles of ferromagnetic material, typically iron oxide (rust), coated on thin ribbons of plastic tape (or, originally, fragile paper tape). The tape coating is magnetized by dragging it over the surface of a small recording head (typically the size of a sugar cube) which contains an electro-magnetic coil.[11][12]

In record mode, the coil becomes an electro-magnet, generating a magnetic field varying with electric current supplied by a low-power amplifier attached to an audio source such as a microphone. As the tape moves over the recording head, the head's magnetic field varies with the sound thus varying the magnetism on the passing particles of metal oxide on the tape.[11]

In playback mode, the recording head becomes a playback head and senses the magnetism of the metallic particles on the tape as the tape was pulled across the head. The head's electromagnet coil translates the varying magnetism into electrical signals which were sent to another amplifier circuit that can power a speaker or headphones, making the recorded sound audible.[11]

More elaborate systems, especially those for professional use, have often been equipped with multiple, separate but adjacent heads, such as a three-head system that uses one head for record, another for playback, and a third for erasing (demagnetizing) the tape. Some may even have multiple record and/or playback heads, for separate tracks or opposite directions of record and/or playback.[11][13][14]

Tape drive

[edit]Two basic systems were developed to drive the tape across the recording head: spool drive and capstan-drive.[11][12]

Most tape recorders move the tape by pinching and pulling it between a motorized capstan, a rotating metal shaft or spindle, and a larger rubber idler roller, called a pinch wheel or pinch roller. This ensures tape speed remained constant as it moved across the recording head regardless of the amount of tape on either reel. Simultaneously, a motor turned the takeup reel to collect and spool the tape as it left the recording head.[12]

A very slight amount of drag is held on the feed reel, to keep tension on the tape, keeping it straight and preventing it from becoming tangled in the machine. A mechanical clutch, brake, or another motor, was used to provide the drag. On most machines, a motor is used to rewind the tape back onto the feed reel after playback.[12]

More elaborate systems, especially those for professional use, are equipped with multiple motors, such as a three-motor system that uses a separate motor for each reel, and a third motor solely to drive the capstan. Such systems may have a motor shaft directly attached to the capstan, to minimize mechanical variations of tape speed caused by indirect linkages; such systems are called direct drive.[11][12][13][14]

Very early or inexpensive tape recorders moved the tape simply by rotating the tape takeup reel. This simplified design requires only one motor. This arrangement results in variable tape speed. As tape accumulates on the motorized takeup reel, the spool of tape gradually increased in diameter, resulting in it pulling the tape across the recording head increasingly faster.[11][12] In certain circumstances, it could result in playback at speeds different from the recording speed, resulting in distorted sound, particularly if the tape was played back on a normal, fixed-speed tape recorder.[12]

Tape speeds

[edit]In general, the faster the speed, the better the reproduction quality. Higher tape speeds spread the signal longitudinally over more tape area, reducing the effects of dropouts that can be audible from the medium, and noticeably improve high-frequency response. Slower tape speeds conserve tape and are useful in applications where sound quality is not critical.

- 15⁄16 inch per second (2.38 cm/s): used for very long-duration recordings (e.g. recording a radio station's entire output in case of complaints).

- 1+7⁄8 in/s (4.76 cm/s): usually the slowest consumer speed, best for long-duration speech recordings.

- 3+3⁄4 in/s (9.53 cm/s): common consumer speed, used on most single-speed domestic machines, reasonable quality for speech and off-air radio recordings.

- 7+1⁄2 in/s (19.05 cm/s): highest consumer speed, also slowest professional; used by most radio stations for copies of commercial announcements.

- 15 in/s (38.1 cm/s): professional music recording and radio programming. Through the early to mid 1990s, equipment in many radio stations did not support this speed.[citation needed]

- 30 in/s (76.2 cm/s): used where the best possible treble response and lowest noise floor are demanded, though bass response might suffer.[15]

Speed units of inches per second or in/s are also abbreviated IPS. 3+3⁄4 in/s and 7+1⁄2 in/s are the speeds that were used for (the vast majority of) consumer market releases of commercial recordings on reel-to-reel tape. 3+3⁄4 in/s is also the speed used in 8-track cartridges. 1+7⁄8 in/s is also the speed used in Compact cassettes.

In some early prototype linear video tape recording systems developed in the early 1950s from companies such as Bing Crosby Enterprises, RCA, and the BBC's VERA, the tape speed was extremely high, over 200 in/s (510 cm/s), to adequately capture the large amount of image information. The need for a high linear tape speed was made unnecessary with the introduction of the professional Quadruplex system in 1956 by Ampex, which segmented the fields of a television image by recording (and reproducing) several tracks at a high-speed across the width of the tape per field of video by way of a vertically spinning headwheel with four separate video heads mounted on its edge (a technique called transverse scanning), allowing for the linear tape speed to be much slower. Eventually, transverse scanning was accompanied by the later (and less-expensive) technology of helical scanning, which could record one whole field of video per helically-recorded track, recorded at a much lower angle across the width of the tape by the head spinning in the near-horizontal plane, instead of vertically.

Quality aspects

[edit]Even though a recording on tape may have been made at studio quality, tape speed is the limiting factor, much like bit rate limits digital recording. Decreasing the speed of analog audio tape causes a uniform decrease in the linearity of the frequency response, increased background noise (hiss), more noticeable dropouts where there are flaws in the magnetic tape, and shifting of the (Gaussian) background noise spectrum toward lower frequencies.

A recording on magnetic audio tape is accessed sequentially. Not only is jumping from spot to spot to edit time-consuming, but editing is also destructive—unless the recording was duplicated before edit, normally taking the same amount of time to copy, in order to preserve 75-90 percent of the quality of the original.

Editing is done either with a razor blade—by physically cutting and splicing the tape on a metal splicing block, in a manner similar to motion picture film editing—or electronically by dubbing segments onto an edit tape. The former method preserves the full quality of the recording but not the intact original; the latter incurred the same quality loss involved in dubbing a complete copy of the source tape but preserved the original.

Tape speed is not the only factor affecting the quality of the recording. Other factors affecting quality include track width, oxide formulation, and backing material and thickness. The design and quality of the recorder are also important factors. The machine's speed stability (wow-and-flutter), head gap size, head quality, and general head design and technology. and the machine's mechanical alignment[b] affect the quality of the recording. The regulation of tape tension affects contact between the tape and the heads and has a significant impact on the recording and reproduction of high frequencies. Due to the cliff effect, all of these performance factors map more directly to quality in analog recordings than in digital.

The track width is one of two major machine factors controlling SNR, the other being tape speed. S/N ratio varies directly with track width, due to the Gaussian nature of tape noise; doubling the track width doubles the SNR. With good electronics and comparable heads, 8-track cartridges should have half the signal-to-noise ratio of quarter-track 1⁄4" tape at the same speed, 3+3⁄4 ips.

Tape formulation affects the retention of the magnetic signal, especially high frequencies, the frequency linearity of the tape, the SNR, and optimum AC bias level.

Backing material type and thickness affect the tensile strength and elasticity of the tape, which affect wow-and-flutter and tape stretch; stretched tape will have a pitch error, possibly fluctuating. Backing material also affects quality aspect, not related to audio quality. Typically, acetate is used for cheaper tape, and Mylar for more expensive tape. Acetate tends to break under conditions that Mylar would survive, though possibly stretch. The quality of the oxide's binder is also important, for it was common with old tape for the oxide and backing to separate.

In the 1980s, several manufacturers produced certain tape formulations blending polyurethane and polyester as backing material which tended to absorb humidity over many years in storage and partially deteriorate. This problem would only be discovered after an archived tape was opened and required to be played again, after possibly a decade or less on the shelf. The deterioration resulted in a softening of the backing material, making it gooey and sticky which quickly clogged-up tape guides and heads of the reproducer. This phenomenon is known as sticky-shed syndrome and can be temporarily reversed by baking the tape at a low temperature for several hours to dry it. The restored tape may then be played normally for several days or weeks, but will eventually return to a deteriorated state again.[16]

Print-through, the phenomenon of adjacent layers of tape wound on a reel picking up weak copies of the magnetic signal from each other. Print-through on analog tape causes unintended pre- and post-echoes on playback and is generally cannot be removed once it has occurred. In professional half-track use, post-echo is considered less problematic than pre-echo, as the echo is largely masked by the signal itself, and therefore tapes stored for long periods are kept tails-out, where the tape must be first wound backward onto a feed spool before playback.

Noise reduction

[edit]Electronic noise reduction techniques were also developed to increase the signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range of analog sound recordings. Dolby noise reduction includes a suite of standards (designated A, B, C, S and SR) for both professional and consumer recording. The Dolby systems use frequency-dependent compression and expansion (companding) during the recording and playback, respectively. Initially, Dolby was offered via a stand-alone box that would go between a recorder and amplifier. Later recorders often included Dolby. DBX is another noise reduction system that uses a more aggressive companding technique to improve both dynamic range and noise level. However, unlike many Dolby systems, DBX recordings do not sound acceptable when played on non-DBX equipment.

In the late 1970s, there was also the German Telefunken-made High Com NR system, a broadband compander that produced a gain in dynamics of roughly 25 dB and outperformed Dolby B but was not widely adopted. High Com was included in more sophisticated cassette recorders, mostly alongside the various Dolby systems.

Dolby B eventually became the most popular system for Compact Cassette noise reduction and Dolby SR was in widespread use for professional analog tape recording.

Multitrack recorders

[edit]As studio audio production techniques advanced, it became desirable to record the individual instruments and human voices separately and mix them down to one, two, or more speaker channels at a later time. Individual tracks can be recorded at different locations at any later date.

Reel-to-reel recorders with eight, sixteen, twenty-four, and even thirty-two tracks were eventually built, with as many heads recording synchronized parallel linear tracks. Some of these machines were larger than a laundry washing machine and used tape as wide as 2 inches (51 mm).

If more tracks were required, it was possible in the mid-1970s and onwards with advanced servo-controlled machines to synchronize two (or more) recorders to behave as a single larger recorder.

Digital reel-to-reel

[edit]As professional audio evolved from analog magnetic tape to digital media, engineers adapted magnetic tape technology to digital recording, producing digital reel-to-reel magnetic tape machines. Before large hard disks became economical enough to make hard disk recorders viable, studio digital recording meant recording on digital tape. Mitsubishi's ProDigi and Sony's Digital Audio Stationary Head (DASH) were the primary digital reel-to-reel formats in use in recording studios from the early 1980s through the mid-1990s. Nagra introduced digital reel-to-reel tape recorders for use in film sound recording.

Best known for its lines of tape media and professional analog recorders, with its M series of multitrack and 2-track machines, the Mincom division of 3M spent several years developing a digital recording system, including two years of joint research with the BBC. The result was the 3M Digital Audio Mastering System, which consisted of a 32-track deck (16-bit, 50 kHz audio) running 1-inch tape and a 4-track, 1/2-inch mastering recorder. 3M's 32-track recorder was priced at $115,000 in 1978 (equivalent to $554,000 in 2024).

Digital reel-to-reel tape eliminated all the traditional quality limitations of analog tape, including background noise (hiss), high frequency roll-off, wow and flutter, pitch error, nonlinearity, print-through, and degeneration with copying, but the tape media was even more expensive than professional analog open reel tape, and the linear nature of tape still placed restrictions on access, and winding time to find a particular spot was still a significant drawback. Also, while the quality of digital tape did not progressively degrade with use of the tape, the physical sliding of the tape over the heads and guides meant that the tape still did wear, and eventually, that wear would lead to digital errors and permanent loss of quality if the tape was not copied before reaching that point.

The extremely short wavelengths used by digital tape formats meant that tape and tape transport cleanliness was an important issue. Specks of dust or dirt were large enough in relation to the signal wavelengths that contamination by such dirt could render a recording unplayable. Advanced digital error correction systems, without which the system would have been unworkable, still failed to cope with poorly maintained tape or recorders, and for this reason a number of tapes made in the early years of digital reel-to-reel recorders are now useless.

Because digital audio recording technology advanced over the years, with development of cassette-based tape recording formats (such as DAT) and tapeless recording, digital reel-to-reel audio recording is now obsolete although many enthusiasts still maintain and use their equipment.

As a musical instrument

[edit]Early reel-to-reel users learned to manipulate segments of tape by splicing them together and adjusting playback speed or direction of recordings. Just as modern keyboards allow sampling and playback at different speeds, a reel-to-reel recorder could accomplish similar tasks in the hands of a talented user.

- In the late 1940s, Les Paul began experimenting with creating a virtual dance band or jazz ensemble, from his solo guitar accompanying his wife, vocalist Mary Ford, by bouncing or overdubbing from one tape machine to another multiple times, layering new vocal or instrument parts on top of previously recorded tracks. While this had been done in the past using phonograph discs, that process was cumbersome and resulted in degraded audio quality after only one or two overdubs. A disc had to be discarded if there was any mistake, but tape was reuseable. Magnetic tape recording allowed Paul to shift instrument sounds to higher or lower octaves by manipulating the speed of the tape while recording his guitar. He used tape echo to enhance ambience or create a special effect. Paul and Mary Ford produced many popular recordings over the next two decades using these techniques. One of their most famous was "How High the Moon".

- In 1958, Ross Bagdasarian, a.k.a. David Seville, recorded his voice at one-half normal speed, raising its pitch a full octave when played back at normal speed, to create the early rock and roll novelty song Witch Doctor. He later used the same technique, plus overdubbing his voice three times, to create the Chipmunks. Many other creators of novelty, comedy, and children's records, such as Sheb Wooley, Sascha Burland, and Ray Stevens have since used this process.

- The mellotron is an electro-mechanical, polyphonic tape replay keyboard that uses a bank of parallel linear magnetic audio tape strips. Playback heads underneath each key enable the playing of pre-recorded sounds. Each of the tape strips has a playing time of approximately eight seconds after which the tape disengages and returns to the start position.

- The title track of Jimi Hendrix's album Are You Experienced, on which the guitar solo and much of the drum track was recorded then played backward on a reel-to-reel.

- The Beatles recorded many songs using reel-to-reel tape as a creative tool. Examples include "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" and "Yellow Submarine" which cut up stock recordings and then randomly spliced and overdubbed them into the songs (recordings of calliope organs on "Mr. Kite", and recordings of marching bands on "Yellow Submarine").[17]: 168 On "Tomorrow Never Knows" multiple tape machines were interconnected to play tape loops that had been prepared by the band. The loops were played backward, sped up or slowed down. To record the song, the tape machines, located in separate rooms, were manned by technicians and played together to record on the fly.[17]: 113 "Strawberry Fields Forever" combined two different taped versions of the song. The versions were independently altered in speed to end up together miraculously both on pitch and tempo.[17]: 139 "I Am the Walrus" used a radio tuner patched into the sound console to layer a random live broadcast over an existing taped track.[17]: 215 "Revolution 9" also had effects produced using a reel-to-reel with tape editing techniques.

- The BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Delia Derbyshire arranged and realised the original theme to the BBC series Doctor Who by recording various sounds including oscillators and then manually cutting together each individual note on a group of reel-to-reels.

- The British rock band 10cc created a human harmonium of sorts on a 16-track tape recorder by overdubbing their own voices many dozens of times, singing only a single note each time. The cumulative result was a total of 630 voices spread evenly over an octave-and-a-half of proper musical scale notes, with each of the distinct notes assigned to an individual track of the tape. When played back, any track (or note) could be faded in and out manually on a mixing console arranged like a piano keyboard, to simulate an immense virtual choir. This effect provided the atmospheric backing instrumentation for their song "I'm Not in Love".[18]

- Argentine blues guitarist Claudio Gabis, needing an amplifier for his electric guitar, used a modified Geloso recorder as a distortion device for his debut album Manal of 1970. This was achieved by injecting a signal and letting it "record under vacuum" (without tape, recording infinitely). The amplified signal thus obtained could be distorted by considerably increasing the volume.[19] Also the first single of the group "Qué pena me das", has an abrupt ending with tapes passed upside down.[20]

- Aaron Dilloway, founding member of Wolf Eyes, often utilizes a reel-to-reel tape machine in his solo performances.[citation needed]

- Yamantaka Eye of the band Boredoms uses a reel-to-reel tape as an instrument in live performances and in post-production (an example is the track "Super You" from the album Super æ).

- Mission of Burma member Martin Swope played a reel-to-reel tape recorder live, either playing previously recorded samples at certain times or recording part of the band's performance and playing it back either in reverse or at different speeds. When the band re-formed in 2002, audio engineer Bob Weston took over Swope's role at the tape deck.

- Musique concrète is a type of music composition that utilizes recorded sounds, typically on reel-to-reel, as raw material.

- Pink Floyd's cash register introduction to their track "Money" was made using a loop of spliced tape which was looped around a mic stand and through a tape player.[21]

- Steve Tibbetts is a recording artist who includes tape editing as a significant portion of the creative process.[22]

- Frank Zappa's Lumpy Gravy,[23] We're Only in It for the Money and Uncle Meat,[24] featured numerous edits, and multiple instances of speed alteration and intricately layered samples upon samples.

- The improviser Jerome Noetinger uses a ReVox A77 reel-to-reel to create and manipulate tape loops in live performance.[25]

- In 2009, musician Ei Wada formed the band Open Reel Ensemble, using old reel-to-reel recordings to create electronic music.[26]

In addition, multiple reel-to-reel machines used in tandem can also be used to create echo and delay effects. The Frippertronics configuration used by Brian Eno and Robert Fripp on their 1970s and '80s recordings illustrates these possibilities.[27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ When it arrived, it was still set up as an instrument recorder running at 60 inches-per-second and had yet to be converted for audio use.

- ^ Alignment is arguably a maintenance issue, but also a matter of design pertaining to how well and precisely the machine can be aligned and how well it can maintain alignment.

References

[edit]- ^ "STM Studiotechnic". Stm.hu. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

- ^ "About Us - RecordingTheMasters". recordingthemasters.com. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Blattnerphone", Orbem.co.uk, retrieved 02 February 2014

- ^ "11 Best Saturation VST Plugins Available 2022". Retrieved 2022-08-23.

- ^ Thom Holmes, Electronic and experimental music, 2nd ed., p. 79

- ^ "Attention Tape Editors—Sound Men—New Tape Splicer 'Editall'." (advertisement) Audio Engineering, May 1951, 52.

- ^ Nicola, Stefan (May 7, 2018). "The Ultimate Analog Music Is Back". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ G. de Richemont (2023). "List of Record Labels releasing pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes". Le Son International.

- ^ "The Tape Project". www.tapeproject.com.

- ^ "Analogue Audio Association - Home". www.aaanalog.de.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fowler, W.S.: "Magnetic Sound Recording," Part 1, February 1963, pages 754, 755, and 756, Practical Wireless, as photo-archived at WorldRadioHistory.com, retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fowler, W.S.: "Magnetic Sound Recording," Part 2, March 1963, page 866, (further details at page 867) Practical Wireless, as photo-archived at WorldRadioHistory.com, retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Feldman, Len: "U.S. Pioneer RT-707 Tape Deck," (review), April 1978, Radio-Electronics, page 61, as photo-archived at WorldRadioHistory.com retrieved May 21, 2023

- ^ a b "Pioneer RT-707 Open-reel Tape Deck," (review), November 1977, Stereo Review, page 52, as photo-archived at WorldRadioHistory.com retrieved May 21, 2023

- ^ Jack Endino. "Response Curves of Analog Recorders". Endino.com. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

- ^ Rarey, Rich. "Baking Old Tapes is a Recipe for Success". Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-08-12.

- ^ a b c d Emrick, Geoff (16 March 2006). Here, There and Everywhere. Penguin. ISBN 9781101218242.

- ^ Presenters: Richard Allinson and Steve Levine (9 May 2009). "The Record Producers – 10cc". The Record Producers. Season 3. Episode 4. BBC. BBC Radio 2.

- ^ Las biografías más salvajes del rock Rolling Stone (Argentina), (in Spanish). Consultado el 9 de abril de 2014.

- ^ Informe especial Manal Dos Potencias (in Spanish).

- ^ "Pink Floyd : Money in Studio VERY RARE!!". YouTube. 2010-08-03. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Ellis, Andy Steve Tibbetts: Zen and the art of sculpting sound. Guitar Player, December 01, 2002

- ^ Graves, Tom (December 1987). "The Rock & Roll Disc Interview: Frank Zappa". Rock & Roll Disc. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ Lowe, Kelly Fisher (October 2007). The Words and Music of Frank Zappa. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803260054. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- ^ "Supercolor Palunar". Lionelpalun.com. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Summers, Nick (July 26, 2018). "The Japanese ensemble making music from old tape reels". Engadget.

- ^ The back cover of Eno's 1975 album Discreet Music shows a diagram of the dual reel-to-reel setup and other components used in recording the selections on that album.

KSF

KSF