Relief (emotion)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

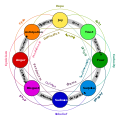

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

Relief is a positive emotion experienced when something unpleasant, painful or distressing has not happened or has come to an end.[1]

Often accompanied by sighing, which signals emotional transition,[2] relief is universally recognized,[3] and judged as a fundamental emotion.[4]

In a 2017 study published in Psychology, relief is suggested to be an emotion that can reinforce anxiety through avoidance[5][6] or be an adaptive coping mechanism when stressed or frustrated.[7]

Types of relief (near-miss and task-completion)

[edit]Relief is often discussed as one concept, but when asking people to think of scenarios where they experienced relief, about half thought of near-miss scenarios, and the other half thought of task-completion scenarios. Near-miss relief is the experience of narrowly avoiding something aversive, e.g. the cancellation of a test for which one forgot to prepare. Task-completed relief is experienced upon finishing an aversive task, e.g. a complicated tax return.[8]

To test whether there really are two distinct types of relief, the researchers created a scenario where people had to sing a song in front of an experiment leader after listening to the song once. In one condition (near-miss) the participants were told they did not have to sing after all. In the other condition (task-completed) they sang the song.

Near-miss relief led to more counterfactual thinking (i.e. "what if it had gone differently"), and also feeling more socially isolated. It appears that near-miss relief triggers people to think more about the scenario for the future, maybe how to avoid something like it happening again. Task-completion relief, on the other hand, might reinforce endurance of difficult tasks.[9]

Reinforcing avoidance

[edit]Others have also suggested that relief can reinforce avoidance, by rewarding the escape from a scary situation, relief might help create pathological avoidance which can maintain anxiety disorders.[10][11] For example, if a nervous person needed to speak before a group, and it was cancelled at the last minute, the relief he would feel from not having to do it could reward the avoidance, and his memory of the relief might prompt him to decline an offer to speak another time: thus fear of public speaking is maintained by the feeling of relief.

Sigh of relief

[edit]It has been found that rats sigh with relief. Because rats are social animals, the researchers suggested that maybe sighing with relief function as a social signal to other rats.[12] We do not know whether sighing is a social signal, however, and when asked in an experiment, people estimated that they sighed as much around others as alone.[13]

When people are given a difficult task, for instance an impossible puzzle, they sigh between attempts or when they give up.[14] When individuals sigh with relief, it is by definition a transition from something negative to a positive state. One dominating theory suggests that sighing with relief causes a reset, both emotionally and physiologically. This reset theory of relief captures how sighing with relief signals the end of a negative state, and resets the individual for another one.[15] If this is true, it explains why the anxious sigh more,[16] and why one working on a difficult mental task will sigh more often.[17] In these scenarios, sighing might be an attempt to induce psychophysiological relief. Based on these findings, it is proposed that sighs regulate stress and negative emotions, which might be an adaptive coping mechanism for the frustrated, the stressed, and the anxious.[18]

See also

[edit]- Anticipation – Emotion involving pleasure or anxiety in considering or awaiting an expected event

- Catharsis – Psychological event that purges emotions

References

[edit]- ^ "relief". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

- ^ Vlemincx, E.; Meulders, M.; Abelson, J. (2017). "Sigh rate during emotional transitions: More evidence for a sigh of relief". Biological Psychology. 125: 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.03.005. PMID 28315375.

- ^ Laukka, P.; Elfenbein, H. A.; Söder, N.; Nordström, H. (2013). "Cross-cultural decoding of positive and negative non-linguistic emotion vocalisations". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 353. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00353. PMC 3728469. PMID 23914178.

- ^ Shaver, P.; Schwartz, J.; Kirson, D.; O’Connor, C. (1987). "Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 52 (6): 1061–1086. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061. PMID 3598857.

- ^ Vervliet, B.; Lange, I.; Milad, M. (2017). "Temporal dynamics of relief in avoidance conditioning and fear extinction: Experimental validation and clinical relevance". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 96: 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2017.04.011. PMID 28457484.

- ^ Deutsch, R.; Smith, K.; Kordts-Freudinger, R.; Reichardt, R. (2015). "How absent negativity relates to affect and motivation: an integrative relief model". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 152. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00152. PMC 4354424. PMID 25806008.

- ^ Vlemincx, E.; Meulders, M.; Abelson, J. (2017). "Sigh rate during emotional transitions: More evidence for a sigh of relief". Biological Psychology. 125: 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.03.005. PMID 28315375.

- ^ Sweeny, K.; Vohs, K. D. (2012). "On near misses and completed tasks: The nature of relief". Psychological Science. 23 (5): 464–468. doi:10.1177/0956797611434590. PMID 22477104. S2CID 5951979.

- ^ Sweeny, K.; Vohs, K. D. (2012). "On near misses and completed tasks: The nature of relief". Psychological Science. 23 (5): 464–468. doi:10.1177/0956797611434590. PMID 22477104. S2CID 5951979.

- ^ Vervliet, B.; Lange, I.; Milad, M. (2017). "Temporal dynamics of relief in avoidance conditioning and fear extinction: Experimental validation and clinical relevance". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 96: 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2017.04.011. PMID 28457484.

- ^ Deutsch, R.; Smith, K.; Kordts-Freudinger, R.; Reichardt, R. (2015). "How absent negativity relates to affect and motivation: an integrative relief model". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 152. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00152. PMC 4354424. PMID 25806008.

- ^ Soltysik, S.; Jelen, P. (2005). "In rats, sighs correlate with relief". Physiology & Behavior. 85 (5): 598–602. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.008. PMID 16038951.

- ^ Teigen, K. (2008). "Is a sigh "just a sigh"? Sighs as emotional signals and responses to a difficult task". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 49 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00599.x. PMID 18190402.

- ^ Teigen, K. (2008). "Is a sigh "just a sigh"? Sighs as emotional signals and responses to a difficult task". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 49 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00599.x. PMID 18190402.

- ^ Vlemincx, E.; Abelson, J.; Lehrer, P.; Davenport, P.; van Diest, I.; van den Bergh, O. (2013). "Respiratory variability and sighing: A psychophysiological reset model". Biological Psychology. 93 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.12.001. PMID 23261937.

- ^ Vlemincx, E.; Meulders, M.; Abelson, J. (2017). "Sigh rate during emotional transitions: More evidence for a sigh of relief". Biological Psychology. 125: 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.03.005. PMID 28315375.

- ^ Teigen, K. (2008). "Is a sigh "just a sigh"? Sighs as emotional signals and responses to a difficult task". Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 49 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00599.x. PMID 18190402.

- ^ Vlemincx, E.; Meulders, M.; Abelson, J. (2017). "Sigh rate during emotional transitions: More evidence for a sigh of relief". Biological Psychology. 125: 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.03.005. PMID 28315375.

KSF

KSF