Rhode Island General Assembly

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Rhode Island General Assembly | |

|---|---|

Seal of the State of Rhode Island | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate House of Representatives |

| History | |

| Founded | Original Charter July 8, 1663 Modern Form January 20, 1987 |

New session started | January 3, 2023 |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

Senate president pro tempore | |

Senate Majority Leader | |

Senate Minority Leader | |

Speaker of the House | |

House Majority Leader | Christopher R. Blazejweski (D) since January 5, 2021 |

House Minority Leader | |

| Structure | |

| Seats |

|

| |

Senate political groups | Majority (33)

Minority (5)

|

| |

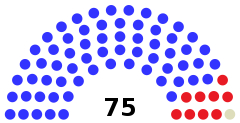

House of Representatives political groups | Majority (65)

Minority (10)

|

| Elections | |

Last Senate election | November 8, 2022 |

Last House of Representatives election | November 8, 2022 |

Next Senate election | November 5, 2024 |

Next House of Representatives election | November 5, 2024 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Rhode Island State House Providence | |

| Website | |

| Rhode Island Legislature | |

| Constitution | |

| Constitution of Rhode Island | |

The State of Rhode Island General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. A bicameral body, it is composed of the lower Rhode Island House of Representatives with 75 representatives, and the upper Rhode Island Senate with 38 senators. Members are elected in the general election immediately preceding the beginning of the term or in special elections called to fill vacancies. There are no term limits for either chamber. The last General Assembly election took place on November 3, 2020.

The General Assembly meets at the Rhode Island State House on the border of Downtown and Smith Hill in Providence. Smith Hill is sometimes used as a metonym for the Rhode Island General Assembly.[1]

History

[edit]Early independence

[edit]On June 12, 1775, the Rhode Island General Assembly met at East Greenwich to pass a resolution creating the first formal, governmentally authorized navy in the Western Hemisphere:

"It is voted and resolved, that the committee of safety be, and they are hereby, directed to charter two suitable vessels, for the use of the colony, and fit out the same in the best manner, to protect the trade of this colony... "That the largest of the said vessels be manned with eighty men, exclusive of officers; and be equipped with ten guns, four-pounders; fourteen swivel guns, a sufficient number of small arms, and all necessary warlike stores. "That the small vessel be manned with a number not exceeding thirty men. "That the whole be included in the number of fifteen hundred men, ordered to be raised in this colony... "That they receive the same bounty and pay as the land forces..."[2][3]

The Rhode Island General Assembly was one of the thirteen colonial legislatures that rejected British rule in the American War of Independence. The General Assembly was the first legislative body during the war to seriously consider independence from Great Britain. On May 4, 1776, five months before the Continental Congress formally adopted the United States Declaration of Independence, Rhode Island became the first colony of what would soon be the future United States to legally leave the British Empire. William Ellery and the first chancellor of Brown University Stephen Hopkins were signatories to the Declaration of Independence for Rhode Island.

A decisive march ending with the defeat of British forces commanded by Charles Cornwallis began in Newport, Rhode Island under the command of French forces sent by King Louis XVI and led by the Comte de Rochambeau. The American forces in the march were jointly led by General George Washington. The march proceeded through Providence, Rhode Island and ended with the defeat of British forces following the Siege of Yorktown at Yorktown, Virginia and the naval Battle of the Chesapeake. Nathanael Greene was a member along with his cousin, Christopher Greene.

Federal debate

[edit]Over a decade after the war, the General Assembly led by the Country Party pushed aside calls to join the newly formed federal government, citing its demands that a Bill of Rights should be included in the new federal U.S. Constitution and its opposition to slavery. With a Bill of Rights under consideration and with an ultimatum from the new federal government of the United States that it would begin to impose export taxes on Rhode Island goods if it did not join the Union, the General Assembly relented. On May 29, 1790, Rhode Island became the last of the Thirteen Colonies to sign the U.S. Constitution, becoming the thirteenth U.S. state (and the smallest).

State constitutions

[edit]From 1663 until 1842, Rhode Island's governing state constitution was its original colonial charter granted by King Charles II of England, a political anomaly considering that while most states during the War of Independence and afterwards wrote scores of new constitutions with their newly found independence in mind, Rhode Island instead continued with a document stamped by an English king. Even nearly seventy years after U.S. independence, Rhode Island continued to operate with the 1663 Charter, leaving it after 1818 (when Connecticut, the other holdout, dropped its colonial charter for a contemporary constitution) the only state whose official legal document was passed by a foreign monarch.

While the 1663 Charter was democratic considering its time period, rising national demands for voting suffrage in response to the Industrial Revolution put strains on the colonial document. By the early 1830s, only 40% of the state's white males could vote, one of the lowest white male voting franchise percentages in the entire United States. For its part, the General Assembly proved to be an obstacle for change, not eager to see its traditional wealthy voting base shrink.

Constitutional reform came to a head in 1841 when supporters of universal suffrage led by Thomas Wilson Dorr, dissatisfied with the conservative General Assembly and the state's conservative governor, Samuel Ward King, held the extralegal People's Convention, calling on Rhode Islanders to debate a new liberal constitution. At the same time, the General Assembly began its own constitution convention dubbed the Freeman's Convention, making some democratic concessions to Dorr supporters, while keeping other aspects of the 1663 Charter intact.

Elections in late 1841 and early 1842 led to both sides claiming to be the legitimate state government, each with their own respective constitutions in hand. In the days following the highly confusing and contentious 1842 gubernatorial and state legislature elections, Governor King declared martial law. Liberal Dorr supporters took up arms to begin the Dorr Rebellion.

The short-lived rebellion proved unsuccessful in overthrowing Governor King and the General Assembly. The Freeman's Constitution eventually was debated upon by the legislature and passed by the electorate. Although not as liberal as the People's document, the 1843 Freeman's Constitution did greatly increase male suffrage in Rhode Island, including ending the racial requirement.[1] Further revisions in the 1843 document were made by the General Assembly and passed by the electorate in 1986.

See also

[edit]- Rhode Island State House

- Rhode Island House of Representatives

- Rhode Island Senate

- List of Rhode Island state legislatures

References

[edit]- ^ Gregg, Katherine. "On Smith Hill, Senators-elect learn the ropes on lawmaking". providencejournal.com. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ "First Navy | The Joseph Bucklin Society". bucklinsociety.net. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "History & Birth Place of the Navy | East Greenwich, RI". www.eastgreenwichri.com. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

External links

[edit]- The State of Rhode Island General Assembly Official Website

- General Assembly digitized records from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Guide to the Rhode Island General Assembly Reapportionment and Redistricting records from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Final Report of the Commission to Study Auto Mechanics and Repair Licensing from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Final Report of the Commission to Study Professional Boxing and Wrestling in Rhode Island from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Final Report of the Joint Special Committee to Consider Changes Relative to Divorce from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Final Report of the Special Legislative Commission to make a Comprehensive Study in the Field of Drug Addiction from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Final Report on the Special Legislative Commission to Study Foster Care in Rhode Island from the Rhode Island State Archives

- First Annual Report of the Board of Food and Drug Commissioners from the Rhode Island State Archives

- General Assembly: Petitions Failed, Withdrawn finding aid from the Rhode Island State Archives

- General Assembly Records finding aid from the Rhode Island State Archives

- General Assembly Speaker Files folder list from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Guide to the General Assembly Joint Committee on Accounts and Claims records from the Rhode Island State Archives

- House Speaker Session Files from the Rhode Island State Archives

- Private Acts of the General Assembly from the Rhode Island State Archives

KSF

KSF