-

Vocer of the one-shot Rigel-Anedonìa (2014)

-

Cover Rigel Interlunium variant edition

-

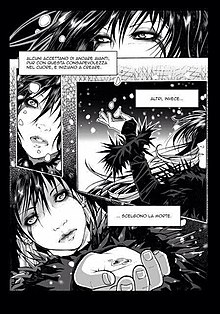

Internal page sample

-

Rigel and Sortilegio, acrylic illustration

-

Rigel, internal illustration

-

Rigel page from the variant edition

-

Elena de' Grimani guest at Romics, stand Panini Comics, 2012

-

Rigel work in progress-ink phase

Rigel (character)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

| Rigel | |

|---|---|

Tavola interna di Rigel | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Panini Comics |

| First appearance | "Rigel Interlunium" (1999) |

| Created by | Elena de' Grimani |

Rigel is a gothic comic series, created by Elena de' Grimani.

Publication history

[edit]

After a first series of three volumes self-produced by the author from '99 to 2001 that did debut at Lucca Comics, Rigel becomes a small "publishing phenomenon",[1] and in fact just two years after its debut, goes to publication with Panini Comics, first with the miniseries "Rigel Interlunium" that will be sold out and reprinted several times (the last in 2012 in deluxe-variant version)[2] and then continue with the monographic Anedonia, giving life to a new narrative arc of the character.[3][4] Rigel Interlunium is not in continuity with self-production.

The titles of the three self-produced volumes are:

- Rigel – La Settima Congrega[4]

- Rigel – Il requiem dell'unicorno

- Rigel – Creature dell'Altrove

The self-production is now sold out since a long time, and in the new chapters produced by Panini Comics (Rigel Interlunium, composed of four volumes of 96 pages each) also participated Fabrizio Palmieri for the screenplay.

Panini Comics then reissued the miniseries twice more times: initially, after the immediate sold out of the first edition, and again in 2012, dedicating to Rigel a variant deluxe edition with sixteen brand new pages and two new covers.[5]

Rigel's self-production was published under the Anatema label. It consists of three volumes plus a "spin-off" untitled Tìnebra.[6]

Interlunium was produced by Panini Comics, under the Cult Comics label and is made up of four volumes published between 2002 and 2004. The Interlunium series, even if it includes some characters from the past self-production, is to be considered completely separated from it. In fact, between self-production and Interlunium there is no continuity. Even the graphic style changes a lot.[2]

The series was followed in 2014 by the one-shot monohraphic book volume Anedonia,[7][8] consisting of 144 pages, again published by Panini Comics in 2014 and entirely written, screened and designed by Elena de' Grimani. The old characters, although not mentioned in this monographic (apart from the cat-familiar "Sortilegio") are always present in the setting of the comic. It is therefore an evolution of the character on a character level, but not a zeroing of the original setting: nothing of what happened in Interlunium is denied or canceled. The self-contained volume "Rigel-Anedonìa" therefore simply means the narration of the phase of passage and change of the nature of Rigel between the two narrative arcs: the old course, and what will come in the future.[7] The metal band Rammstein authorized the full use of "Sonne" lyrics for a whole sequence of the book.[7]

Other episodes of Rigel have been published in the Vampire and Concrete anthology magazines published by Absoluteblack.[9]

In 2008 a special monographic book with Rigel as main character, with the title Gioco di Sangue,[10] is published by Cartoon Club as "one shot" for the "Rimini Comix" comicbook fair.[11]

Characters

[edit]Rigel

[edit]Rigel is a vampire of about eight centuries.

She's a "child chosen by the fire". It possesses, in other words, particular powers due to a particularly powerful and rare blood (only seven girls for each generation have this type of blood). Because of this his parents, accused of witchcraft, were burned on the Death at the stake fire when she was very young. Or at least this is the version that has always been told, as Rigel remembers very little of his past as a human.[12]

He continued to live with his aunt and uncle brother Caleb (of whom he has not remembered since he was a vampire) and the cat Sortilegio. Meanwhile, one sorcerer and vampire, Artemius, began to study her, introducing herself to her as imaginary friend and ending, once she grew up, for fall in love. At [Caleb's death (for reasons still unknown to readers), Rigel attempted suicide.[13] She was found almost bloodless by Artemius, who, in order not to lose her, turned her into a vampire. To allow this, since the blood left in Rigel was not enough, he gave her half his soul. Being a character created by the author in 1999, with the passing of the years and of the publications, Rigel has undergone various evolutions both graphic and of character.

In the monographic Rigel-Anedonìa released in 2014 for Panini Comics,[3] the vampire manages to free herself from her "human side" after ten years of "torpor".[3] The setting and the supporting characters will remain the same (as far as in this monographic see only Sortilegio), and the "world" of the character remains the same as "Rigel-Interlunium". It is the nature of the character itself that changes, without anything that has been narrated in "Interlunium" being denied or canceled, including supporting characters and settings. In fact, "Rigel-Anedonìa" is a passage book between the old and the new narrative arc.[14]

As is well-specified in the introduction of the last released graphic novel, it is not by chance that this monograph is titled "Anedonia": this passage story in fact is meant to be a metaphor of depression, on how to isolate from the world (Rigel in fact "disappears" hiding under the ground for ten years, letting herself go into a "torpor" as a clear will and decision to close all contacts, and at the same time "emprisons" metaphorically his human part – that was her peculiar characteristic, the only thing that made her able to experience feelings and emotions, making her different from other undeads, in a "glass sphere" that isolates her soul from everything, and then continues to live in the real world but without being able to "taste" anything, thus protecting itself from pain ... but also from positive feelings.[15]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ettore Gabrielli (21 January 2004). "Nell'Ombra: Elena De' Grimani" (in Italian).

- ^ a b Luca Ceretti. "Rigel – Interlunium". uBCfumetti.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.

- ^ a b c ""Rigel Anedonia": il ritorno del personaggio di Elena de' Grimani a Lucca Comics & Games". Lo Spazio Bianco (in Italian). 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b Luca Ceretti. "Rigel – La Settima Congrega". uBCfumetti.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Rigel: Interlunium: torna nelle fumetterie l'opera di Elena de' Grimani e Fabrizio Palmieri" (in Italian). 27 September 2012.

- ^ Luca Cerutti. "Tinebra del mondo parallelo". uBCfumetti.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on 25 March 2016.

- ^ a b c ""Rigel Anedonia": il ritorno del personaggio di Elena de' Grimani a Lucca Comics & Games". Lo Spazio Bianco. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Sonia Rocca (1 December 2014). "Rigel Anedonia" (in Italian).

- ^ "Absolute Black: di qualunque colore purché sia nero". Fumetto d'Autore (in Italian). Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Rigel: Gioco di sangue (in Italian). ISSN 1129-499X. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "A piazzale Fellini di Rimini prosegue Cartoon Club". altarimini.it (in Italian). Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ "Speciale Rigel di Elena de' Grimani". 21 January 2014.

- ^ "Speciale Rigel". February 1998.

- ^ "Rigel Anedonia" (in Italian). 14 December 2014.

- ^ Alessandro Bottero (24 February 2015). "Recensione Rigel Anedonia (Panini Comics)". Fumetto d'Autore (in Italian).

References

[edit]- Anima dark (a cura della Redazione). In: Scuola di Fumetto n. 23, Coniglio Editore, October 2004

- Gianni Bono (25 April 2015). "Rigel". Guida al Fumetto italiano (in Italian).

- Valentina Semprini, Chiamateli fumetti: le contaminazioni di Rigel, su Fumo di China n.72, ed. Cartoon Club Editore, November 1999, p. 34/

- Luca Boschi, sezione in "And the Oscar goes to…". Su Annuario del Fumetto 2002, Cartoon Club Editore, 2002, p. 58. [Rigel compare nella top five dell'anno]

- Egisto Quinti Seriacopi, recensione a "Rigel: Anedonia", su Fumo di China n. 237, Cartoon Club Editore, April 2015, p. 24

- Dario Morgante, Non possiamo che essere indipendenti. Su: Annuario del Fumetto 2000, Cartoon Club Editore, 2000, pp. 40–42.

- Sergio Rossi, La narrativa fantasy a fumetti in Italia. Su: Annuario del Fumetto 2001, Cartoon Club Editore, 2001, pp. 8–12.

KSF

KSF