Roy Innis

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

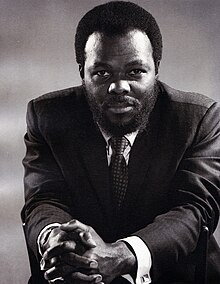

Roy Innis | |

|---|---|

Innis circa 1970 | |

| 4th National director of the Congress of Racial Equality | |

| In office 1968 – January 8, 2017 | |

| Preceded by | Wilfred Ussery |

| Succeeded by | TBD |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roy Emile Alfredo Innis June 6, 1934 Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands |

| Died | January 8, 2017 (aged 82) New York City, United States |

| Cause of death | Parkinson's disease |

| Political party | Libertarian (1998–death) Democratic (1986–1998) |

| Spouse | Doris Funnye Innis |

| Children | 10, including Niger Innis |

| Occupation | Activist and politician |

Roy Emile Alfredo Innis (June 6, 1934 – January 8, 2017) was an American activist and politician. He was National Chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)[1] from 1968 until his death.

One of his sons, Niger Roy Innis, serves as National Spokesman of the Congress of Racial Equality.

Early life

[edit]Innis was born in Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands in 1934.[2][3] In 1947, Innis moved with his mother from the U.S. Virgin Islands to New York City, where he graduated from Stuyvesant High School in 1952.[4] At age 16, Innis joined the U.S. Army, and at age 18 he received an honorable discharge. He entered a four-year program in chemistry at the City College of New York. He subsequently held positions as a research chemist at Vick Chemical Company and Montefiore Hospital.[5]

Early civil rights years

[edit]Innis joined CORE's Harlem chapter in 1963. In 1964 he was elected chairman of the chapter's education committee and advocated community-controlled education and black empowerment.[3] In 1965, he was elected Chairman of Harlem CORE, after which he campaigned for the establishment of an independent Board of Education for Harlem.

In early 1967, Innis was appointed the first resident fellow at the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC), headed by Dr. Kenneth Clark. In the summer of 1967, he was elected Second National Vice-chairman of CORE.

Additionally that year, Innis became a founding member of the Harlem Commonwealth Council (HCC), a community action agency that has aimed to develop financial and human capital within upper Manhattan and Bronx communities. The HCC was established under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty campaign.[6]

From 1968 to 1972, Innis co-published the Manhattan Tribune newspaper with journalist and Robert Kennedy presidential campaign advisor, William Haddad. The periodical aimed to cover news concerning the Upper West Side and Harlem from both a black and white American perspective. Haddad was quoted, “Roy, for example, thinks I’m a soft, fuzzy white liberal and we disagree 80 percent of the time, but we have to live together in this little inner city, and the only solution lies in an honest and uninhibited dialogue.” [7]

Leadership of CORE

[edit]Innis was selected National Chairman of CORE in 1968 a contentious convention meeting.[8][9] Innis initially headed the organization in a strong campaign of black nationalism. White CORE activists, according to James Peck, were removed from CORE in 1965, as part of a purge of whites from the movement then under the control of Innis.[10] Under Innis' leadership, CORE supported the presidential candidacy of Richard Nixon in 1972. This was the beginning of a sharp rightward turn in the organization.[11]

During his leadership, Innis paid a visit to Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson the Lubavitcher Rebbe, remarking that despite what the media says, his people sympathize with the Jewish community and that he wishes to express his condolences after the Crown Heights riots of 1991. The Rebbe pointed out the similar experiences of the African Americans and the Jews with regard to persecution, and gave his blessing that the United States should be truly united and that its entire population should have good news and healthy news. The Rebbe ended off by saying to Clarence Jackson (Innis's assistant) that his remarks are "also of your concern, to me, to you, and to all the people around us. This means that it is a united cause for all of us." The Rebbe repeated this to every member of Innis's entourage.[12]

Politics

[edit]Innis co-drafted the Community Self-Determination Act of 1968 and garnered bipartisan sponsorship of this bill by one-third of the U.S. Senate and over 50 congressmen. This was the first time in U.S. history that CORE or any civil rights organization drafted a bill and introduced it into the United States Congress.[13] It was introduced to Congress by New York senator Charles Goodell. In 1969 Innis appeared on William F. Buckley Jr.'s Firing Line elaborating on the main goals of CORE's proposed Community Self-Determination Act.[14][15]

In the debate over school integration, Innis offered an alternative plan consisting of community control of educational institutions. As part of this effort, in October 1970, CORE filed an amicus curiae brief with the U.S. Supreme Court in connection with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971).[3][clarification needed]

Innis and a CORE delegation toured seven African countries in 1971. He met with several heads of state, including Kenya's Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania's Julius Nyerere, Liberia's William Tolbert and Uganda's Idi Amin, all of whom were awarded life memberships to CORE.[16] Innis met with Amin and the aforementioned African statesmen as part of his CORE campaign drive for finding jobs in Africa for black Americans. In 1973 he became the first American to attend the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in an official capacity.

In 1973, Innis was scheduled to participate in a televised debate with Nobel-winning physicist William Shockley on the topic of black intelligence. According to sources, Innis pulled out of the debate at the last moment because the student society at Princeton University organizing the event refused to allow the press and the public into the event. The debate went forward with Dr. Ashley Montagu replacing Innis.[17] However a debate between Innis and Shockley on the issue of I.Q. and race did take place at the Commonwealth Club of California on August 23, 1974.[18]

In 1984 Roy Innis led an initiative as described in a CORE publication, The CORELATOR, "A Call for Black Americans to Develop Bold New Political Strategies" and explained in another article, "Why We Must Desegregate the Republican Party." He was quoted by The New York Times in 1984, "The successful desegregation of the Republican Party can be one of the most important and healthy political developments for the black community and for the country at large".[19]

By 1983, Innis already had the support of U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Particularly, Innis' vision for black America. When the President was questioned on his perceived failure to connect with America's black leadership, he was quoted, "now what constitutes black leadership? I have been meeting with an awful lot of people that have—I think, achieved quite some prominence in their work in that field. And, as I say, Roy Innis of CORE, he sees this exactly the same way. I'm perfectly willing to say these same things to the people that are in the organizations where a few of the leaders seem to be, very frankly, more interested in some political differences than they are in resolving the problem."[20]

In 1987, Innis testified at the confirmation hearings for Judge Robert H. Bork along with several other noteworthy speakers such as economist and social commentator Thomas Sowell. Innis made his testimony before then Delaware Senator, Joe Biden.[21] Innis was quoted by The Washington Times that his aim was to, "erase the misconception that all civil rights organizations are against him."[22]

-

Roy Innis appearance on Firing Line in 1969 interviewed by William F. Buckley Jr.

-

Roy Innis (2nd from left) and then wife Doris Funnye Innis (center) with a delegation from CORE is greeted by Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta (left).

-

Roy Innis with CORE aide Solomon Goodrich (right), awarding Julius Nyerere (center) CORE lifetime membership

-

Roy Innis awarding Jomo Kenyatta CORE lifetime membership

Criminal justice and National Rifle Association

[edit]Innis was long active in criminal justice matters, including the debate over gun control and the Second Amendment. After losing two sons to criminals with guns, he became an advocate for the rights of law-abiding citizens to self-defense.[23] A Life Member of the National Rifle Association of America (NRA),[23] he also served on its governing board.[24][25] Innis also chaired the NRA's Urban Affairs Committee and was a member of the NRA Ethics Committee, and continued to speak publicly in the US and around the world in favor of individual civilian ownership of firearms, gun issues, and individual rights.[23]

Innis lost two of his sons to criminal gun violence.[26] His eldest son, Roy Innis, Jr., was killed at the age of 13 in 1968. His next oldest son Alexander, 26, was shot and slain in 1982.[27] Innis told Newsday in 1993 "My sons were not killed by the KKK or David Duke. They were murdered by young, black thugs. I use the murder of my sons by black hoodlums to shift the problems from excuses like the KKK to the dope pushers on the streets."[28]

Controversy

[edit]Innis was noted for two on-air fights in the middle of TV talk shows in 1988. The first occurred in the midst of an argument about the Tawana Brawley case during a taping of The Morton Downey Jr. Show, when Innis shoved Al Sharpton to the floor.[29] Also that year, Innis was in a scuffle on Geraldo with white supremacist John Metzger.[30] The skirmish started after Metzger, son of White Aryan Resistance founder Tom Metzger, called Innis an "Uncle Tom." Innis grabbed the seated Metzger's throat, appearing to choke him.[31][32] The incident started a brawl in the studio, resulting in Rivera's nose getting broken.[33]

Innis raised American volunteers to fight for UNITA, an Angolan rebel army fighting the communist government.[34] UNITA was also supported by Uganda[3] and apartheid-era South Africa.

Prosperity USA, a non-profit run by aides of presidential candidate Herman Cain, attracted controversy after it gave a $100,000 donation to CORE shortly before Cain's speech at a CORE event.[35]

Political campaigns

[edit]In 1986, Innis challenged incumbent Major Owens in the Democratic primary for the 12th Congressional District, representing Brooklyn. He was defeated by a three-to-one margin.

In the 1993, New York City Democratic Party mayoral primary, Innis challenged incumbent David Dinkins, the first African-American to hold the office. Given his conservative positions on the issues, he explained that "the Democratic Party is the only game in town. It's unfortunate that we have a corrupt one-party, one ideology system in New York City, and I'd like to change that. But being a Democrat doesn't mean you have to be a fool." During his own campaign, Innis also appeared at fundraising events for the Republican candidate Rudolph Giuliani. Innis received 25% of the vote in the four-way race with a majority of his votes coming from multi-ethnic areas, while he failed in less culturally diverse Assembly Districts. Innis lost to Dinkins, who then lost to Giuliani in the general election.

In February 1994, Niger, who ran his primary campaign, suggested that Innis would also challenge incumbent governor Mario Cuomo in the Democratic primary.

In 1998, Innis joined the Libertarian Party and gave serious consideration to running for Governor of New York as the party's candidate that year. He ultimately decided against running, citing time restrictions related to his duties with CORE.[36]

Innis served as New York State Chair in Alan Keyes's 2000 presidential campaign.[37]

Death

[edit]Innis died on January 8, 2017, at the age of 82, from Parkinson's disease.[2]

Bibliography

[edit]- Frazier, Nishani (2017). Harambee City: Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1682260186.

References

[edit]- ^ Grandia, Kevin. "Roy Innis". DeSmog. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ a b McFadden, Robert D. (10 January 2017). "Roy Innis, Black Activist With a Right-Wing Bent, Dies at 82". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d "Roy Innis, Public Policy Activist born". African American Registry. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ Hicks, Jonathan (1993-05-25). "Innis Campaign for Mayor: A Quixotic Quest?". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Executive Staff – Roy Innis". Congress of Racial Equality.

- ^ "Our Story".

- ^ "William F. Haddad, journalist, political operative and businessman, dies at 91". The Washington Post. 2020-05-03. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (10 January 2017). "Roy Innis, Black Activist With a Right-Wing Bent, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Langer, Emily (2017-01-09). "Roy Innis, embattled leader of the Congress of Racial Equality, dies at 82". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "Interview with James Peck". Eyes on the Prize. 26 October 1979. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ Nishani, Frazier (2017). Harambee City : the Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the rise of Black Power populism. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 171–182, 185–205. ISBN 9781610756013. OCLC 973832475.

- ^ "The Lubavitcher Rebbe with Roy Innis - 1991". YouTube. 3 June 2020.

- ^ Nishani, Frazier (2017). Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. pp. 185–206. ISBN 9781610756013. OCLC 973832475.

- ^ "Firing Line (Television Program) broadcast records".

- ^ "Firing Line Roy Innis - Urban Development and the Race Question". YouTube. 12 November 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Alison (1993-09-13). "Mayoral Race Is Overshadowed In New York Primary Tomorrow". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ^ Rheinhold, Robert (December 5, 1973)."Shockley Debates Montagu as Innis Angrily Pulls Out". The New York Times.

- ^ "Debate Concerning the Idea of Racial I.Q. Deficits".

- ^ "Congress of Racial Equality Urges Blacks to Back G.O.P." 4 November 1984.

- ^ Bernard Weinraub; Hedrick Smith; Leslie H. Gelb; Gerald M. Boyd (12 February 1985). "Transcript of Interview With President on a Range of Issues". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Bork Nomination Day 11, Part 5". C-SPAN. National Cable Satellite Corporation. September 29, 1987. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Gene Grabowski (28 September 1987). "Innis asks to testify in support of Bork" (PDF). The Washington Times. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "Inside NRA: NRA Board Spotlight". American Rifleman. April 2010. p. 77.

- ^ "'Ricochet' Goes Behind Scenes of Gun Lobby". National Public Radio. 2007-11-15. Archived from the original on 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2007-11-15.

- ^ "Roy Innis re-elected to NRA Board", NRAwinningteam.com. Archived October 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Roy Innis- Civil Rights Activist". www.myblackhistory.net. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ "The City; 2d Innis Son Slain". New York Times. 1982-02-23. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Roy Innis, conservative civil rights crusader who embraced gun rights, dies at 82". New York Daily News. 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2017-01-12.

- ^ "Innis Shoves Sharpton To Floor at TV Taping". The New York Times. August 10, 1988.

- ^ Rosenberg, Howard (November 28, 1988). "The New Odd Couple: Metzger, Innis Take Their Feud on Road". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera's Nose Broken In Scuffle on His Talk Show". New York Times. November 4, 1988. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

I'm sick and tired of Uncle Tom here, sucking up and trying to be a white man, Mr. Metzger said of Mr. Innis, the national chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality. Mr. Innis stood up and began choking the white youth and Mr. Rivera and audience members joined the scuffle, hurling chairs, throwing punches and shouting epithets. 'Racist Thugs Are Like Roaches'

- ^ Frazier, Nishani (2017). Harambee City : the Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the rise of Black Power populism. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. p. xxv. ISBN 9781610756013. OCLC 973832475.

- ^ John Carmody "Geraldo Rivera Injured in Meless During Taping" The Washington Post, November 4, 1988 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1988/11/04/geraldo-rivera-injured-in-melee-during-taping/14166cd2-bc3d-4871-9a97-2dc3a23bc2f3/

- ^ "The Morning Record". news.google.com. Retrieved 5 November 2018 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ Eggen, Dan (2011-10-31). "Herman Cain campaign's financial ties to Wisconsin charity questioned". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- ^ "Innis passes on NY governor's run; mulls New York mayor race in 2001". May 1998. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ "Roy & Niger Innis Endorse Alan Keyes for President of the United States" (Press release). 2000-02-11. Archived from the original on 2008-07-19.

External links

[edit]- CORE's Official Website

- A history of Harlem CORE

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Harambee City: Archival site incorporating documents, maps, audio/visual materials related to CORE's work in black power and black economic development.

KSF

KSF