Russia

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 117 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 117 min

Russian Federation Российская Федерация (Russian) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Государственный гимн Российской Федерации Gosudarstvennyy gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii "State Anthem of the Russian Federation" | |

| Capital and largest city | Moscow 55°45′21″N 37°37′02″E / 55.75583°N 37.61722°E |

| Official and national language | Russian[3] |

| Recognised regional languages | 35 regional official languages[4] |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Demonym(s) | Russian |

| Government | Federal semi-presidential republic[6] under an authoritarian[7][8] dictatorship[9][10] |

| Vladimir Putin | |

| Mikhail Mishustin | |

| Legislature | Federal Assembly |

| Federation Council | |

| State Duma | |

| Formation | |

| 882 | |

| 1157 | |

| 1282 | |

| 16 January 1547 | |

| 2 November 1721 | |

| 15 March 1917 | |

| 30 December 1922 | |

| 12 June 1990 | |

| 12 December 1991 | |

| 12 December 1993 | |

| 8 December 1999 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,098,246 km2 (6,601,670 sq mi)[12] (within internationally recognised borders) |

• Water (%) | 13[11] (including swamps) |

| Population | |

• 2025 estimate | (9th) |

• Density | 8.4/km2 (21.8/sq mi) (187th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2023) | very high (64th) |

| Currency | Russian ruble (₽) (RUB) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 to +12 |

| Calling code | +7 |

| ISO 3166 code | RU |

| Internet TLD | |

Russia,[b] or the Russian Federation,[c] is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the largest country in the world, and extends across eleven time zones, sharing land borders with fourteen countries.[d] With over 140 million people, Russia is the most populous country in Europe and the ninth-most populous in the world. It is a highly urbanised country, with sixteen of its urban areas having more than 1 million inhabitants. Moscow, the most populous metropolitan area in Europe, is the capital and largest city of Russia, while Saint Petersburg is its second-largest city and cultural centre.

Human settlement on the territory of modern Russia dates back to the Lower Paleolithic. The East Slavs emerged as a recognised group in Europe between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE. The first East Slavic state, Kievan Rus', arose in the 9th century, and in 988, it adopted Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire. Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated; the Grand Duchy of Moscow led the unification of Russian lands, leading to the proclamation of the Tsardom of Russia in 1547. By the early 18th century, Russia had vastly expanded through conquest, annexation, and the efforts of Russian explorers, developing into the Russian Empire, which remains the third-largest empire in history. However, with the Russian Revolution in 1917, Russia's monarchic rule was abolished and eventually replaced by the Russian SFSR—the world's first constitutionally socialist state. Following the Russian Civil War, the Russian SFSR established the Soviet Union with three other Soviet republics, within which it was the largest and principal constituent. The Soviet Union underwent rapid industrialisation in the 1930s, amidst the deaths of millions under Joseph Stalin's rule, and later played a decisive role for the Allies in World War II by leading large-scale efforts on the Eastern Front. With the onset of the Cold War, it competed with the United States for ideological dominance and international influence. The Soviet era of the 20th century saw some of the most significant Russian technological achievements, including the first human-made satellite and the first human expedition into outer space.

In 1991, the Russian SFSR emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union as the Russian Federation. A new constitution was adopted, which established a federal semi-presidential system. Since the turn of the century, Russia's political system has been dominated by Vladimir Putin, under whom the country has experienced democratic backsliding and become an authoritarian dictatorship. Russia has been militarily involved in a number of conflicts in former Soviet states and other countries, including its war with Georgia in 2008 and its war with Ukraine since 2014. The latter has involved the internationally unrecognised annexations of Ukrainian territory, including Crimea in 2014 and four other regions in 2022, during an ongoing invasion.

Russia is generally considered a great power and is a regional power, possessing the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons and having the third-highest military expenditure in the world. It has a high-income economy, which is the eleventh-largest in the world by nominal GDP and fourth-largest by PPP, relying on its vast mineral and energy resources, which rank as the second-largest in the world for oil and natural gas production. However, Russia ranks very low in international measurements of democracy, human rights and freedom of the press, and also has high levels of perceived corruption. It is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council; a member state of the G20, SCO, BRICS, APEC, OSCE, and WTO; and the leading member state of post-Soviet organisations such as CIS, CSTO, and EAEU. Russia is home to 32 UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Etymology

[edit]According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English name Russia first appeared in the 14th century, borrowed from Medieval Latin: Russia, used in the 11th century and frequently in 12th-century British sources, in turn derived from Russi, 'the Russians' and the suffix -ia.[19][20]

There are several words in Russian which translate to "Russians" in English. The noun and adjective русский, russkiy refers to ethnic Russians. The adjective российский, rossiiskiy denotes Russian citizens regardless of ethnicity. The same applies to the more recently coined noun россиянин, rossiianyn, in the sense of citizen of the Russian state.[21][22]

The oldest endonyms used were Rus' (Русь) and the "Russian land" (Русская земля, Russkaya zemlya).[23] According to the Primary Chronicle, the word Rus' is derived from the Rus' people, who were a Swedish tribe, and from where the three original members of the Rurikid dynasty came from.[24] The Finnish word for Swedes, ruotsi, has the same origin.[25] In modern historiography, the early medieval East Slavic state is usually referred to as Kievan Rus', named after its capital city.[26] Another Medieval Latin name for Rus' was Ruthenia.[27]

In Russian, the current name of the country, Россия (Rossiya), comes from the Byzantine Greek name Ρωσία (Rosía).[28] The name Росия (Rosiya) was first attested in 1387.[29] The name Rossiya appeared in Russian sources in the 15th century and began to replace the vernacular Rus' during the rise of Moscow as the centre of a unified Russian state.[30] However, until the end of the 17th century, the country was more often referred to by its inhabitants as Rus', the "Russian land" (Russkaya zemlya), or the "Muscovite state" (Moskovskoye gosudarstvo), among other variations.[31][21]

In 1721, Peter the Great proclaimed the Russian Empire (Rossiyskaya imperiya).[31] The name Rossiya was used as the common designation for the multinational Russian Empire and then for the modern Russian state.[32] Rossiya is distinguished from the ethnonym russkiy, as it refers to a supranational identity, including ethnic Russians.[32] After the Russian Revolution and the proclamation of the Russian SFSR in 1918, the "Russian" in the title of the state was Rossiyskaya, rather than Russkaya, as the former denoted a multinational state, while the latter had ethnic dimensions.[33] In modern Russian, the name Rus' is still used in poetry or prose to refer to either the older Russia or an imagined essence of Russia.[26]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The first human settlement on Russia dates back to the Oldowan period in the early Lower Paleolithic. About 2 million years ago, representatives of Homo erectus migrated to the Taman Peninsula in southern Russia.[34] Flint tools, some 1.5 million years old, have been discovered in the North Caucasus.[35] Radiocarbon dated specimens from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains estimate the oldest Denisovan specimen lived 195–122,700 years ago.[36] Fossils of Denny, an archaic human hybrid that was half Neanderthal and half Denisovan, and lived some 90,000 years ago, was also found within the latter cave.[37] Russia was home to some of the last surviving Neanderthals, from about 45,000 years ago, found in Mezmaiskaya cave.[38]

The first trace of an early modern human in Russia dates back to 45,000 years, in Western Siberia.[39] The discovery of high concentration cultural remains of anatomically modern humans, from at least 40,000 years ago, was found at Kostyonki–Borshchyovo,[40] and at Sungir, dating back to 34,600 years ago—both in western Russia.[41] Humans reached Arctic Russia at least 40,000 years ago, in Mamontovaya Kurya.[42] Ancient North Eurasian populations from Siberia genetically similar to Mal'ta–Buret' culture and Afontova Gora were an important genetic contributor to Ancient Native Americans and Eastern Hunter-Gatherers.[43]

The Kurgan hypothesis places the Volga-Dnieper region of southern Russia and Ukraine as the urheimat of the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[45] Early Indo-European migrations from the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Ukraine and Russia spread Yamnaya ancestry and Indo-European languages across large parts of Eurasia.[46][47] Nomadic pastoralism developed in the Pontic–Caspian steppe beginning in the Chalcolithic.[48] Remnants of these steppe civilisations were discovered in places such as Ipatovo,[48] Sintashta,[49] Arkaim,[50] and Pazyryk,[51] which bear the earliest known traces of horses in warfare.[49] The genetic makeup of speakers of the Uralic language family in northern Europe was shaped by migration from Siberia that began at least 3,500 years ago.[52]

In the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the Gothic kingdom of Oium existed in southern Russia, which was later overrun by Huns. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, the Bosporan Kingdom, which was a Hellenistic polity that succeeded the Greek colonies,[53] was also overwhelmed by nomadic invasions led by warlike tribes such as the Huns and Eurasian Avars.[54] The Khazars, who were of Turkic origin, ruled the steppes between the Caucasus in the south, to the east past the Volga river basin, and west as far as Kyiv on the Dnieper river until the 10th century.[55] After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks.[56]

The ancestors of Russians are among the Slavic tribes that separated from the Proto-Indo-Europeans, who appeared in the northeastern part of Europe c. 1500 years ago.[57] The East Slavs gradually settled western Russia (approximately between modern Moscow and Saint-Petersburg) in two waves: one moving from Kiev towards present-day Suzdal and Murom and another from Polotsk towards Novgorod and Rostov.[58] Prior to Slavic migration, that territory was populated by Finno-Ugrian peoples. From the 7th century onwards, the incoming East Slavs slowly assimilated the native Finno-Ugrians.[59][60]

Kievan Rus'

[edit]

The establishment of the first East Slavic states in the 9th century coincided with the arrival of Varangians, the Vikings who ventured along the waterways extending from the eastern Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas.[59][61] According to the Primary Chronicle, a Varangian from the Rus' people, named Rurik, was elected ruler of Novgorod in 862. In 882, his successor Oleg ventured south and conquered Kiev, which had been previously paying tribute to the Khazars.[59][61] Rurik's son Igor and Igor's son Sviatoslav subsequently subdued all local East Slavic tribes to Kievan rule, destroyed the Khazar Khaganate,[62] and launched several military expeditions to Bulgaria, Byzantium and Persia.[63][64]

In the 10th to 11th centuries, Kievan Rus' became one of the largest and most prosperous states in Europe. The reigns of Vladimir the Great (980–1015) and his son Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054) constitute the Golden Age of Kiev, which saw the acceptance of Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium, and the creation of the first East Slavic written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda.[59] The age of feudalism and decentralisation had come, marked by constant in-fighting between members of the Rurik dynasty that ruled Kievan Rus' collectively. Kiev's dominance waned, to the benefit of Vladimir-Suzdal in the north-east, the Novgorod Republic in the north, and Galicia-Volhynia in the south-west.[59] By the 12th century, Kiev lost its pre-eminence and Kievan Rus' had fragmented into different principalities.[65] Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky sacked Kiev in 1169 and made Vladimir his base,[65] leading to political power being shifted to the north-east.[59]

Led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, Novgorodians repelled the invading Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in 1240,[66] as well as the Germanic crusaders in the Battle on the Ice in 1242.[67]

Kievan Rus' finally fell to the Mongol invasion of 1237–1240, which resulted in the sacking of Kiev and other cities, as well as the death of a major part of the population.[59] The invaders, later known as Tatars, formed the state of the Golden Horde, which ruled over Russia for the next two centuries.[68] Only the Novgorod Republic escaped foreign occupation after it agreed to pay tribute to the Mongols.[59] Galicia-Volhynia would later be absorbed by Lithuania and Poland, while the Novgorod Republic continued to prosper in the north. In the northeast, the Byzantine-Slavic traditions of Kievan Rus' were adapted to form the Russian autocratic state.[59]

Grand Principality of Moscow

[edit]

The destruction of Kievan Rus' saw the eventual rise of the Grand Principality of Moscow, initially a part of Vladimir-Suzdal.[59]: 11–20 While still under the domain of the Mongol-Tatars and with their connivance, Moscow began to assert its influence in the region in the early 14th century,[69] gradually becoming the leading force in the "gathering of the Russian lands".[59][70] When the seat of the Metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church moved to Moscow in 1325, its influence increased.[71] Moscow's last rival, the Novgorod Republic, prospered as the chief fur trade centre and the easternmost port of the Hanseatic League.[72]

Led by Prince Dmitry Donskoy of Moscow, the united army of Russian principalities inflicted a milestone defeat on the Mongol-Tatars in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380.[59] Moscow gradually absorbed its parent duchy and surrounding principalities, including formerly strong rivals such as Tver and Novgorod.[59]

Ivan III ("the Great") threw off the control of the Golden Horde and gained sovereignty over the ethnically Russian lands;[59] he later adopted the title of sovereign of all Russia.[73] After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow claimed succession to the legacy of the Eastern Roman Empire. Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI, and made the Byzantine double-headed eagle his own, and eventually Russia's, coat-of-arms.[59] Vasili III united all of Russia by annexing the last few independent Russian states in the early 16th century.[74]

Tsardom of Russia

[edit]

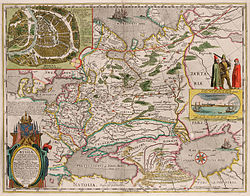

In development of the Third Rome ideas, the grand prince Ivan IV ("the Terrible") was officially crowned as the first tsar of all Russia in 1547. The tsar promulgated a new code of laws (Sudebnik of 1550), established the first Russian feudal representative body (the Zemsky Sobor), revamped the military, curbed the influence of the clergy, and reorganised local government.[59] During his long reign, Ivan nearly doubled the already large Russian territory by annexing the three Tatar khanates: Kazan and Astrakhan along the Volga,[75] and the Khanate of Sibir in southwestern Siberia. Ultimately, by the end of the 16th century, Russia expanded east of the Ural Mountains.[76] However, the Tsardom was weakened by the long and unsuccessful Livonian War against the coalition of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (later the united Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), the Kingdom of Sweden, and Denmark–Norway for access to the Baltic coast and sea trade.[77] In 1572, an invading army of Crimean Tatars were thoroughly defeated in the crucial Battle of Molodi.[78]

The death of Ivan's sons marked the end of the ancient Rurik dynasty in 1598, and in combination with the disastrous famine of 1601–1603, led to a civil war, the rule of pretenders, and foreign intervention during the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century.[79] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, taking advantage, occupied parts of Russia, extending into the capital Moscow.[80] In 1612, the Poles were forced to retreat by the Russian volunteer corps, led by merchant Kuzma Minin and prince Dmitry Pozharsky.[81] The Romanov dynasty acceded to the throne in 1613 by the decision of the Zemsky Sobor, and the country started its gradual recovery from the crisis.[82]

Russia continued its territorial growth through the 17th century, which was the age of the Cossacks.[83] In 1654, the Ukrainian leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, offered to place Ukraine under the protection of the Russian tsar, Alexis, whose acceptance of this offer led to another Russo-Polish War. Ultimately, Ukraine was split along the Dnieper, leaving the eastern part, (Left-bank Ukraine and Kiev) under Russian rule.[84] In the east, the rapid Russian exploration and colonisation of vast Siberia continued, hunting for valuable furs and ivory. Russian explorers pushed eastward primarily along the Siberian River Routes, and by the mid-17th century, there were Russian settlements in eastern Siberia, on the Chukchi Peninsula, along the Amur River, and on the coast of the Pacific Ocean.[83] In 1648, Semyon Dezhnyov became the first European to navigate through the Bering Strait.[85]

Imperial Russia

[edit]Under Peter the Great, Russia was proclaimed an empire in 1721, and established itself as one of the European great powers. Ruling from 1682 to 1725, Peter defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War (1700–1721), securing Russia's access to the sea and sea trade. In 1703, on the Baltic Sea, Peter founded Saint Petersburg as Russia's new capital. Throughout his rule, sweeping reforms were made, which brought significant Western European cultural influences to Russia.[59] He was succeeded by Catherine I (1725–1727), followed by Peter II (1727–1730), and Anna. The reign of Peter I's daughter Elizabeth in 1741–1762 saw Russia's participation in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). During the conflict, Russian troops overran East Prussia, reaching Berlin.[86] However, upon Elizabeth's death, all these conquests were returned to the Kingdom of Prussia by pro-Prussian Peter III of Russia.[87]

Catherine II ("the Great"), who ruled in 1762–1796, presided over the Russian Age of Enlightenment. She extended Russian political control over the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and annexed most of its territories into Russia, making it the most populous country in Europe.[88] In the south, after the successful Russo-Turkish Wars against the Ottoman Empire, Catherine advanced Russia's boundary to the Black Sea, by dissolving the Crimean Khanate, and annexing Crimea.[89] As a result of victories over Qajar Iran through the Russo-Persian Wars, by the first half of the 19th century, Russia also conquered the Caucasus.[90] Catherine's successor, her son Paul, was unstable and focused predominantly on domestic issues.[91] Following his short reign, Catherine's strategy was continued with Alexander I's (1801–1825) wresting of Finland from the weakened Sweden in 1809,[92] and of Bessarabia from the Ottomans in 1812.[93] In North America, the Russians became the first Europeans to reach and colonise Alaska.[94] In 1803–1806, the first Russian circumnavigation was made.[95] In 1820, a Russian expedition discovered the continent of Antarctica.[96]

Great power and development of society, sciences, and arts

[edit]

During the Napoleonic Wars, Russia joined alliances with various European powers, and fought against France. The French invasion of Russia at the height of Napoleon's power in 1812 reached Moscow, but eventually failed as the obstinate resistance in combination with the bitterly cold Russian winter led to a disastrous defeat of invaders, in which the pan-European Grande Armée faced utter destruction. Led by Mikhail Kutuzov and Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly, the Imperial Russian Army ousted Napoleon and drove throughout Europe in the War of the Sixth Coalition, ultimately entering Paris.[97] Alexander I controlled Russia's delegation at the Congress of Vienna, which defined the map of post-Napoleonic Europe.[98]

The officers who pursued Napoleon into Western Europe brought ideas of liberalism back to Russia, and attempted to curtail the tsar's powers during the abortive Decembrist revolt of 1825.[99] At the end of the conservative reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855), a zenith period of Russia's power and influence in Europe, was disrupted by defeat in the Crimean War.[100]

Great liberal reforms and capitalism

[edit]

Nicholas's successor Alexander II (1855–1881) enacted significant changes throughout the country, including the emancipation reform of 1861.[101] These reforms spurred industrialisation, and modernised the Imperial Russian Army, which liberated much of the Balkans from Ottoman rule in the aftermath of the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War.[102] During most of the 19th and early 20th century, Russia and Britain colluded over Afghanistan and its neighbouring territories in Central and South Asia; the rivalry between the two major European empires came to be known as the Great Game.[103]

The late 19th century saw the rise of various socialist movements in Russia. Alexander II was assassinated in 1881 by revolutionary terrorists.[104] The reign of his son Alexander III (1881–1894) was less liberal but more peaceful.[105]

Constitutional monarchy and World War

[edit]Under last Russian emperor, Nicholas II (1894–1917), the Revolution of 1905 was triggered by the humiliating failure of the Russo-Japanese War.[106] The uprising was put down, but the government was forced to concede major reforms (Russian Constitution of 1906), including granting freedoms of speech and assembly, the legalisation of political parties, and the creation of an elected legislative body, the State Duma.[107]

Revolution and civil war

[edit]

In 1914, Russia entered World War I in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Russia's ally Serbia,[108] and fought across multiple fronts while isolated from its Triple Entente allies.[109] In 1916, the Brusilov Offensive of the Imperial Russian Army almost completely destroyed the Austro-Hungarian Army.[110] However, the already-existing public distrust of the regime was deepened by the rising costs of war, high casualties, and rumors of corruption and treason. All this formed the climate for the Russian Revolution of 1917, carried out in two major acts.[59] In early 1917, Nicholas II was forced to abdicate; he and his family were imprisoned and later executed during the Russian Civil War.[111] The monarchy was replaced by a shaky coalition of political parties that declared itself the Provisional Government,[112] and proclaimed the Russian Republic. On 19 January [O.S. 6 January], 1918, the Russian Constituent Assembly declared Russia a democratic federal republic (thus ratifying the Provisional Government's decision). The next day the Constituent Assembly was dissolved by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.[59]

An alternative socialist establishment co-existed, the Petrograd Soviet, wielding power through the democratically elected councils of workers and peasants, called soviets. The rule of the new authorities only aggravated the crisis in the country instead of resolving it, and eventually, the October Revolution, led by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Provisional Government and gave full governing power to the soviets, leading to the creation of the world's first socialist state.[59] The Russian Civil War broke out between the anti-communist White movement and the Bolsheviks with its Red Army.[113] In the aftermath of signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that concluded hostilities with the Central Powers of World War I, Bolshevist Russia surrendered most of its western territories, which hosted 34% of its population, 54% of its industries, 32% of its agricultural land, and roughly 90% of its coal mines.[114]

The Allied powers launched an unsuccessful military intervention in support of anti-communist forces.[115] In the meantime, both the Bolsheviks and White movement carried out campaigns of deportations and executions against each other, known respectively as the Red Terror and White Terror.[116] By the end of the violent civil war, Russia's economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged, and as many as 10 million perished during the war, mostly civilians.[117] Millions became White émigrés,[118] and the Russian famine of 1921–1922 claimed up to five million victims.[119]

Soviet Union

[edit]

Command economy and Soviet society

[edit]On 30 December 1922, Lenin and his aides formed the Soviet Union, by joining the Russian SFSR into a single state with the Byelorussian, Transcaucasian, and Ukrainian republics.[120] Eventually internal border changes and annexations during World War II created a union of 15 republics, the largest in size and population being the Russian SFSR, which dominated the union politically, culturally, and economically.[121]

Following Lenin's death in 1924, a troika was designated to take charge. Eventually Joseph Stalin, the General Secretary of the Communist Party, managed to suppress all opposition factions and consolidate power in his hands to become the country's dictator by the 1930s.[122] Leon Trotsky, the main proponent of world revolution, was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929,[123] and Stalin's idea of Socialism in One Country became the official line.[124] The continued internal struggle in the Bolshevik party culminated in the Great Purge.[125]

Stalinism and modernisation

[edit]

Under Stalin's leadership, the government launched a command economy, industrialisation of the largely rural country, and collectivisation of its agriculture. During this period of rapid economic and social change, millions of people were sent to penal labour camps, including many political convicts for their suspected or real opposition to Stalin's rule,[126] and millions were deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union.[127] The transitional disorganisation of the country's agriculture, combined with the harsh state policies and a drought,[128] led to the Soviet famine of 1932–1933, which killed 5.7[129] to 8.7 million, 3.3 million of them in the Russian SFSR.[130] The Soviet Union, ultimately, made the costly transformation from a largely agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse within a short span of time.[131]

World War II and United Nations

[edit]

The Soviet Union entered World War II on 17 September 1939 with its invasion of Poland,[132] in accordance with a secret protocol within the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany.[133] The Soviet Union later invaded Finland,[134] and occupied and annexed the Baltic states,[135] as well as parts of Romania.[136]: 91–95 On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union,[137] opening the Eastern Front, the largest theater of World War II.[138]: 7

Eventually, some 5 million Red Army troops were captured by the Nazis;[139]: 272 the latter deliberately starved to death or otherwise killed 3.3 million Soviet POWs, and a vast number of civilians, as the "Hunger Plan" sought to fulfil Generalplan Ost.[140]: 175–186 Although the Wehrmacht had considerable early success, their attack was halted in the Battle of Moscow.[141] Subsequently, the Germans were dealt major defeats first at the Battle of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942–1943,[142] and then in the Battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943.[143] Another German failure was the Siege of Leningrad, in which the city was fully blockaded on land between 1941 and 1944 by German and Finnish forces, and suffered starvation and more than a million deaths, but never surrendered.[144] Soviet forces steamrolled through Eastern and Central Europe in 1944–1945 and captured Berlin in May 1945.[145] In August 1945, the Red Army invaded Manchuria and ousted the Japanese from Northeast Asia, contributing to the Allied victory over Japan.[146]

The 1941–1945 period of World War II is known in Russia as the Great Patriotic War.[147] The Soviet Union, along with the United States, the United Kingdom and China were considered the Big Four of Allied powers in World War II, and later became the Four Policemen, which was the foundation of the United Nations Security Council.[148]: 27 During the war, Soviet civilian and military death were about 26–27 million,[149] accounting for about half of all World War II casualties.[150]: 295 The Soviet economy and infrastructure suffered massive devastation, which caused the Soviet famine of 1946–1947.[151] However, at the expense of a large sacrifice, the Soviet Union emerged as a global superpower.[152]

Superpower and Cold War

[edit]

After World War II, according to the Potsdam Conference, the Red Army occupied parts of Eastern and Central Europe, including East Germany and the eastern regions of Austria.[153] Dependent communist governments were installed in the Eastern Bloc satellite states.[154] After becoming the world's second nuclear power,[155] the Soviet Union established the Warsaw Pact alliance,[156] and entered into a struggle for global dominance, known as the Cold War, with the rivalling United States and NATO.[157]

Khrushchev Thaw reforms and economic development

[edit]After Stalin's death in 1953 and a short period of collective rule, the new leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and launched the policy of de-Stalinization, releasing many political prisoners from the Gulag labour camps.[158] The general easement of repressive policies became known later as the Khrushchev Thaw.[159] At the same time, Cold War tensions reached its peak when the two rivals clashed over the deployment of the United States Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Soviet missiles in Cuba.[160]

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, thus starting the Space Age.[161] Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth, aboard the Vostok 1 crewed spacecraft on 12 April 1961.[162]

Period of developed socialism or Era of Stagnation

[edit]Following the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964, another period of collective rule ensued, until Leonid Brezhnev became the leader. The era of the 1970s and the early 1980s was later designated as the Era of Stagnation. The 1965 Kosygin reform aimed for partial decentralisation of the Soviet economy.[163] In 1979, after a communist-led revolution in Afghanistan, Soviet forces invaded the country, ultimately starting the Soviet–Afghan War.[164] In May 1988, the Soviets started to withdraw from Afghanistan, due to international opposition, persistent anti-Soviet guerrilla warfare, and a lack of support by Soviet citizens.[165]

Perestroika, democratisation and Russian sovereignty

[edit]

From 1985 onwards, the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who sought to enact liberal reforms in the Soviet system, introduced the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to end the period of economic stagnation and to democratise the government.[166] This, however, led to the rise of strong nationalist and separatist movements across the country.[167] Prior to 1991, the Soviet economy was the world's second-largest, but during its final years, it went into a crisis.[168]

By 1991, economic and political turmoil began to boil over as the Baltic states chose to secede from the Soviet Union.[169] On 17 March, a referendum was held, in which the vast majority of participating citizens voted in favour of changing the Soviet Union into a renewed federation.[170] In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin became the first directly elected President in Russian history when he was elected President of the Russian SFSR.[171] In August 1991, a coup d'état attempt by members of Gorbachev's government, directed against Gorbachev and aimed at preserving the Soviet Union, instead led to the end of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[172] On 25 December 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, along with contemporary Russia, fourteen other post-Soviet states emerged.[173]

Independent Russian Federation

[edit]Transition to a market economy and political crises

[edit]

The economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union led Russia into a deep and prolonged depression. During and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, wide-ranging reforms including privatisation and market and trade liberalisation were undertaken, including radical changes along the lines of "shock therapy".[174] The privatisation largely shifted control of enterprises from state agencies to individuals with inside connections in the government, which led to the rise of Russian oligarchs.[175] Many of the newly rich moved billions in cash and assets outside of the country in an enormous capital flight.[176] The depression of the economy led to the collapse of social services—the birth rate plummeted while the death rate skyrocketed,[177][178] and millions plunged into poverty,[179] while extreme corruption,[180] as well as criminal gangs and organised crime rose significantly.[181]

In late 1993, tensions between Yeltsin and the Russian parliament culminated in a constitutional crisis which ended violently through military force. During the crisis, Yeltsin was backed by Western governments, and over 100 people were killed.[182]

Modern liberal constitution, international cooperation and economic stabilisation

[edit]In December, a referendum was held and approved, which introduced a new constitution, giving the president enormous powers.[183] The 1990s were plagued by armed conflicts in the North Caucasus, both local ethnic skirmishes and separatist Islamist insurrections.[184] From the time Chechen separatists declared independence in the early 1990s, an intermittent guerrilla war was fought between the rebel groups and Russian forces.[185] Terrorist attacks against civilians were carried out by Chechen separatists, claiming the lives of thousands of Russian civilians.[e][186]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia assumed responsibility for settling the latter's external debts.[187] In 1992, most consumer price controls were eliminated, causing extreme inflation and significantly devaluing the rouble.[188] High budget deficits coupled with increasing capital flight and inability to pay back debts, caused the 1998 Russian financial crisis, which resulted in a further GDP decline.[189]

Movement towards a modernised economy, political centralisation and democratic backsliding

[edit]On 31 December 1999, President Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned,[190] handing the post to the recently appointed prime minister and his chosen successor, Vladimir Putin.[191] Putin then won the 2000 presidential election,[192] and defeated the Chechen insurgency in the Second Chechen War.[193]

Putin won a second presidential term in 2004.[194] High oil prices and a rise in foreign investment saw the Russian economy and living standards improve significantly.[195] Putin's rule increased stability, while transforming Russia into an authoritarian state.[196] In 2008, Putin took the post of prime minister, while Dmitry Medvedev was elected President for one term, to hold onto power despite legal term limits;[197] this period has been described as a "tandemocracy".[198]

Following a diplomatic crisis with neighbouring Georgia, the Russo-Georgian War took place during 1–12 August 2008, resulting in Russia recognising two separatist states in the territories that it occupies in Georgia.[199] It was the first European war of the 21st century.[200] The 2008 constitutional amendments saw the terms of the president extend to six years and the lower house (State Duma) to five years.[201] Putin then went on to win the 2012 presidential election, which fueled the "Snow Revolution" protests.[202]

Invasion of Ukraine

[edit]In early 2014, following a pro-Western revolution in neighbouring Ukraine, Russia annexed Crimea after a disputed referendum on the status of Crimea was staged under Russian occupation.[203][204] The annexation generated an insurgency in the Donbas region of Ukraine, supported by Russian military intervention as part of an undeclared war against Ukraine.[205] Russian mercenaries and military forces, with the support of local separatist militias, waged a war in eastern Ukraine against the new Ukrainian government after the Russian government fostered anti-government and pro-Russian protests in the region,[206] although most residents had opposed secession from Ukraine.[207] Amidst nationwide protests against corruption,[208] Putin was re-elected for his second consecutive term in the 2018 presidential election.[209]

In a major escalation of the conflict, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.[210] The invasion marked the largest conventional war in Europe since World War II,[211] and was met with international condemnation,[212] as well as expanded sanctions against Russia.[213]

As a result, Russia was expelled from the Council of Europe in March,[214] and was suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council in April.[215] In September, following successful Ukrainian counteroffensives,[216] Putin announced a "partial mobilisation", Russia's first mobilisation since Operation Barbarossa.[217] In the end of September, Putin proclaimed the annexation of four partially-occupied Ukrainian regions, the largest annexation in Europe since World War II.[218] Putin and Russian-installed leaders signed treaties of accession, internationally unrecognised and widely denounced as illegal.[218] As a result of the invasion, hundreds of thousands of people are estimated to have been killed or injured,[219][220] while Russia has been accused of numerous war crimes.[221][222][223] The war in Ukraine has further exacerbated Russia's demographic crisis.[224]

In June 2023, the Wagner Group, a private military contractor fighting for Russia in Ukraine, declared an open rebellion against the Russian Ministry of Defence, capturing Rostov-on-Don, before beginning a march on Moscow. However, after negotiations between Wagner and the Belarusian government, the rebellion was called off.[225][226] The leader of the rebellion, Yevgeny Prigozhin, was later killed in a plane crash.[227] Putin won his third consecutive term in the 2024 presidential election, by winning 88% of the vote, the highest percentage in a presidential election in post-Soviet Russia.[228]

Geography

[edit]

Russia's vast landmass stretches over the easternmost part of Europe and the northernmost part of Asia.[229][230] It spans the northernmost edge of Eurasia and has the world's fourth-longest coastline, of over 37,653 km (23,396 mi).[f][232] Russia lies between latitudes 41° and 82° N, and longitudes 19° E and 169° W, extending some 9,000 km (5,600 mi) east to west, and 2,500 to 4,000 km (1,600 to 2,500 mi) north to south.[233] Russia, by landmass, is larger than three continents,[g] and has the same surface area as Pluto.[234]

Russia has nine major mountain ranges, and they are found along the southernmost regions, which share a significant portion of the Caucasus Mountains (containing Mount Elbrus, which at 5,642 m (18,510 ft) is the highest peak in Russia and Europe);[6] the Altai and Sayan Mountains in Siberia; and in the East Siberian Mountains and the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Russian Far East (containing Klyuchevskaya Sopka, which at 4,750 m (15,584 ft) is the highest active volcano in Eurasia).[235][229] The Ural Mountains, running north to south through the country's west, are rich in mineral resources, and form the traditional boundary between Europe and Asia.[236] The lowest point in Russia and Europe, is situated at the head of the Caspian Sea, where the Caspian Depression reaches some 29 metres (95.1 ft) below sea level.[237]

Russia, as one of the world's only three countries bordering three oceans,[230] has links with a great number of seas.[h][229] Its major islands and archipelagos include Novaya Zemlya, Franz Josef Land, Severnaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island, the Kuril Islands (four of which are disputed with Japan), and Sakhalin.[238][239] The Diomede Islands, administered by Russia and the United States, are just 3.8 km (2.4 mi) apart;[240] and Kunashir Island of the Kuril Islands is merely 20 km (12.4 mi) from Hokkaido, Japan.[2]

Russia, home of over 100,000 rivers,[230] has one of the world's largest surface water resources, with its lakes containing approximately one-quarter of the world's liquid fresh water.[229] Lake Baikal, the largest and most prominent among Russia's fresh water bodies, is the world's deepest, purest, oldest and most capacious fresh water lake, containing over one-fifth of the world's fresh surface water.[241] Ladoga and Onega in northwestern Russia are two of the largest lakes in Europe.[230] Russia is second only to Brazil by total renewable water resources.[242] The Volga in western Russia, widely regarded as Russia's national river, is the longest river in Europe and forms the Volga Delta, the largest river delta in the continent.[243] The Siberian rivers of Ob, Yenisey, Lena, and Amur are among the world's longest rivers.[244]

Climate

[edit]The size of Russia and the remoteness of many of its areas from the sea result in the dominance of the humid continental climate throughout most of the country, except for the tundra and the extreme southwest. Mountain ranges in the south and east obstruct the flow of warm air masses from the Indian and Pacific oceans, while the European Plain spanning its west and north opens it to influence from the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.[229] Most of northwest Russia and Siberia have a subarctic climate, with extremely severe winters in the inner regions of northeast Siberia (mostly Sakha, where the Northern Pole of Cold is located with the record low temperature of −71.2 °C or −96.2 °F),[238] and more moderate winters elsewhere. Russia's vast coastline along the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Arctic islands have a polar climate.[229]

The coastal part of Krasnodar Krai on the Black Sea, most notably Sochi, and some coastal and interior strips of the North Caucasus possess a humid subtropical climate with mild and wet winters.[229] In many regions of East Siberia and the Russian Far East, winter is dry compared to summer, while other parts of the country experience more even precipitation across seasons. Winter precipitation in most parts of the country usually falls as snow. The westernmost parts of Kaliningrad Oblast and some parts in the south of Krasnodar Krai and the North Caucasus have an oceanic climate.[229] The region along the Lower Volga and Caspian Sea coast, as well as some southernmost slivers of Siberia, possess a semi-arid climate.[245]

Throughout much of the territory, there are only two distinct seasons, winter and summer, as spring and autumn are usually brief.[229] The coldest month is January (February on the coastline); the warmest is usually July. Great ranges of temperature are typical. In winter, temperatures get colder both from south to north and from west to east. Summers can be quite hot, even in Siberia.[246] Climate change in Russia is causing more frequent wildfires,[247] and thawing the country's large expanse of permafrost.[248]

Biodiversity

[edit]Russia, owing to its gigantic size, has diverse ecosystems, including polar deserts, tundra, forest tundra, taiga, mixed and broadleaf forest, forest steppe, steppe, semi-desert, and subtropics.[249] About half of Russia's territory is forested,[6] and it has the world's largest area of forest,[250] which sequester some of the world's highest amounts of carbon dioxide.[250][251]

Russian biodiversity includes 12,500 species of vascular plants, 2,200 species of bryophytes, about 3,000 species of lichens, 7,000–9,000 species of algae, and 20,000–25,000 species of fungi. Russian fauna is composed of 320 species of mammals, over 732 species of birds, 75 species of reptiles, about 30 species of amphibians, 343 species of freshwater fish (high endemism), approximately 1,500 species of saltwater fishes, 9 species of cyclostomata, and approximately 100–150,000 invertebrates (high endemism).[249][252] Approximately 1,100 rare and endangered plant and animal species are included in the Russian Red Data Book.[249]

Russia's entirely natural ecosystems are conserved in nearly 15,000 specially protected natural territories of various statuses, occupying more than 10% of the country's total area.[249] They include 45 biosphere reserves,[253] 64 national parks, and 101 nature reserves.[254] Although in decline, the country still has many ecosystems which are still considered intact forest, mainly in the northern taiga areas, and the subarctic tundra of Siberia.[255] Russia had a Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.02 in 2019, ranking 10th out of 172 countries, and the first ranked major nation globally.[256]

Government and politics

[edit]

Russia, by constitution, is a symmetric federal republic with a semi-presidential system, wherein the president is the head of state,[257] and the prime minister is the head of government.[6][258] It is structured as a multi-party representative democracy,[258] with the federal government composed of three branches:[259]

- Legislative: The bicameral Federal Assembly of Russia, made up of the 450-member State Duma and the 170-member Federation Council,[259] adopts federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse and the power of impeachment of the president.[260]

- Executive: The president is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, and appoints the Government of Russia (Cabinet) and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies.[257] The president may issue decrees of unlimited scope, so long as they do not contradict the constitution or federal law.[261]

- Judiciary: The Constitutional Court, Supreme Court and lower federal courts, whose judges are appointed by the Federation Council on the recommendation of the president,[259] interpret laws and can overturn laws they deem unconstitutional.[262]

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term and may be elected no more than twice.[263][i] Ministries of the government are composed of the premier and his deputies, ministers, and selected other individuals; all are appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister (whereas the appointment of the latter requires the consent of the State Duma). United Russia is the dominant political party in Russia, and has been described as "big tent" and the "party of power".[265][266]

Post-Soviet Russia was a flawed democracy during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin.[267]: 223 However, following the presidencies of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, it has experienced significant democratic backsliding.[267]: 223 [268][269] The political system evolved from electoral authoritarianism into a consolidated authoritarian regime.[267]: 323 [270] Some political scientists have characterized Putin as the head of a dictatorship,[8][9][271] or a personalist regime.[272][273][270] Putin's second tenure as president has led to further autocratization,[267]: 512 [274]: 80–81 which has been the most significant since the Soviet era,[275][276] with some authors suggesting a regeneration of totalitarian elements.[277][278] Putin's ruling policies are generally referred to as Putinism.[279]

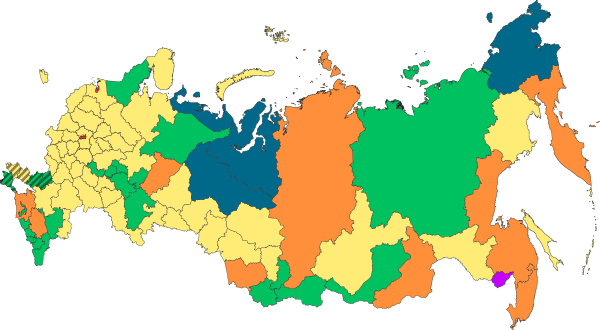

Political divisions

[edit]Russia, by constitution, is a symmetric (with the possibility of an asymmetric configuration) federation. Unlike the Soviet asymmetric model of the RSFSR, where only republics were "subjects of the federation", the current constitution raised the status of other regions to the level of republics and made all regions equal with the title "subject of the federation". The regions of Russia have reserved areas of competence, but regions do not have sovereignty, do not have the status of a sovereign state, do not have the right to indicate any sovereignty in their constitutions and do not have the right to secede from the country. The laws of the regions cannot contradict federal laws.[280]

The federal subjects[j] have equal representation—two delegates each—in the Federation Council, the upper house of the Federal Assembly.[260] They do, however, differ in the degree of autonomy they enjoy.[281] The federal districts of Russia were established by Putin in 2000 to facilitate central government control of the federal subjects.[282] Originally seven, currently there are eight federal districts, each headed by an envoy appointed by the president.[283]

| Federal subjects | Governance |

|---|---|

46 oblasts

|

The most common type of federal subject with a governor and locally elected legislature. Commonly named after their administrative centres.[284] |

22 republics

|

Each is nominally autonomous—home to a specific ethnic minority, and has its own constitution, language, and legislature, but is represented by the federal government in international affairs.[285] |

9 krais

|

For all intents and purposes, krais are legally identical to oblasts. The title "krai" ("frontier" or "territory") is historic, related to geographic (frontier) position in a certain period of history. The current krais are not related to frontiers.[286] |

| Occasionally referred to as "autonomous district", "autonomous area", and "autonomous region", each with a substantial or predominant ethnic minority.[287] | |

| Major cities that function as separate regions (Moscow and Saint Petersburg, as well as Sevastopol in Russian-occupied Ukraine).[288] | |

1 autonomous oblast

|

The only autonomous oblast is the Jewish Autonomous Oblast.[289] |

Foreign relations

[edit]

Russia has the world's sixth-largest diplomatic network as of 2024[update]. It maintains diplomatic relations with 187 United Nations member states, two partially-recognised states,[290] and two United Nations observer states, along with 143 embassies.[291] Russia is one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. It is generally described as a great power,[292][293][294][295] though it has been questioned whether it can retain this status.[296][297] Russia is also a former superpower as the leading constituent of the former Soviet Union.[152] and the legal successor to Soviet foreign policies.[298] It is a member of the G20, the OSCE, and the APEC—and the leading member of organisations such as the CIS,[299] the EAEU,[300] the CSTO,[301] and the SCO.[302] Russia was also a member of the G8 (now the G7) and part of the Council of Europe before its expulsion from the two groups in 2014 and 2022, respectively.[303][304]

Russia maintains close relations with neighbouring Belarus, which is a part of the Union State, a supranational confederation of the two states.[305] Serbia has been a historically close ally of Russia, as both countries share a strong mutual cultural, ethnic, and religious affinity.[306] From the 21st century, relations between Russia and China have significantly strengthened bilaterally and economically due to shared political interests.[307] India is the largest customer of Russian military equipment, and the two countries share a strong strategic and diplomatic relationship since the Soviet era.[308] Russia wields great political influence across the geopolitically important South Caucasus and Central Asia, and the two regions have been described as being part of Russia's "backyard"[309][310] or "near abroad".[298][311]

Countries on Russia's "Unfriendly countries list". The list includes countries that have imposed sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia shares a complex strategic, energy, and defence relationship with Turkey.[312] It maintains cordial relations with Iran, as it is a strategic and economic ally.[313] Russia has also significantly developed its relations with North Korea following its invasion of Ukraine in 2022, with increased defence co-operation.[314] At the same time, its relations with neighbouring Ukraine and the Western world—specifically the United States and the collective countries of the European Union and NATO—have collapsed.[315][316]

In the 21st century, Russia has pursued an aggressive foreign policy aimed at securing regional dominance in Europe and increasing its international influence, as well as increasing domestic support for the government. It has initiated military interventions in the post-Soviet states of Georgia and Ukraine, as well as in Syria during its prolonged civil war in a bid to increase its influence in the Middle East.[317] Russia has also increasingly pushed to expand its influence across the Arctic,[318] the Asia–Pacific,[319] Africa[320] and Latin America.[321] Two-thirds of the world's population, specifically the developing countries of the Global South, are either neutral or leaning towards Russia politically.[322][323] Russia has also continued using subversive tactics to increase perceptions of its geopolitical power in its rival countries,[324][292] including cyberwarfare, disinformation campaigns,[325] sabotage attacks,[326] assassination attempts,[327] airspace violations,[328] electoral interferences,[329] and nuclear saber-rattling.[330]

Military

[edit]

The Russian Armed Forces are divided into the Ground Forces, the Navy, and the Aerospace Forces—and there are also two independent arms of service: the Strategic Missile Troops and the Airborne Troops.[332][6] As of 2025[update], the military have 1.1 million active-duty personnel, which is the world's fifth-largest, and about 1.5 million reserve personnel.[333] It is mandatory for all male citizens aged 18–27 to be drafted for a year of service in the Armed Forces.[6]

Russia is among the five recognised nuclear-weapons states, with the world's largest stockpile of nuclear weapons; over half of the world's nuclear weapons are owned by Russia.[334] Russia possesses the second-largest fleet of ballistic missile submarines,[335] and is one of the only three countries operating strategic bombers.[336] As of 2023[update], Russia maintains the world's third-highest military expenditure, spending $109 billion, corresponding to about 5.9% of its GDP.[337] It is also the third-largest arms exporter,[337] and has a large and indigenous defence industry, which produces the majority of its military equipment.[338][339][340]

Human rights

[edit]Violations of human rights in Russia have been increasingly reported by leading democracy and human rights groups. In particular, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch say that Russia is not democratic and allows few political rights and civil liberties to its citizens.[341][342]

Since 2004, Freedom House has ranked Russia as "not free" in its Freedom in the World survey.[343] Since 2011, the Economist Intelligence Unit has ranked Russia as an "authoritarian regime" in its Democracy Index, ranking it 150th out of 167 countries in 2024.[344] In regards to media freedom, Russia was ranked 162nd out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders' Press Freedom Index for 2024.[345] The Russian government has been widely criticised by political dissidents and human rights activists for unfair elections,[346] crackdowns on opposition political parties and protests,[347][348] persecution of non-governmental organisations and enforced suppression and killings of independent journalists,[349][350][351] and censorship of mass media and internet.[352]

Muslims, especially Salafis, have faced persecution in Russia.[354][355] To quash the insurgency in the North Caucasus, Russian authorities have been accused of indiscriminate killings,[356] arrests, forced disappearances, and torture of civilians.[357][358] In Dagestan, some Salafis along with facing government harassment based on their appearance, have had their homes blown up in counterinsurgency operations.[359][360] Chechens and Ingush in Russian prisons reportedly take more abuse than other ethnic groups.[361] During the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia has set up filtration camps where many Ukrainians are subjected to abuses and forcibly sent to Russia; the camps have been compared to those used in the Chechen Wars.[362][363] Political repression also increased following the start of the invasion, with laws adopted that establish punishments for "discrediting" the armed forces.[364]

Russia has introduced several restrictions on LGBTQ rights. In 2013, an anti-LGBTQ law banning "gay propaganda" was unanimously passed by the State Duma and the Federation Council, later being signed into law by Vladimir Putin.[365] In 2020, the Russian parliament legalized a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage,[366] and in 2021 the Ministry of Justice designated the LGBTQ rights group Russian LGBT Network as a "foreign agent".[367] In 2022, further amendments were made to the 2013 anti-LGBTQ law.[368] In 2023, the Russian parliament passed a bill banning gender reassignment surgery for transgender people and the Supreme Court of Russia banned the international LGBTQ movement as "extremist", outlawing it in the country.[369][370] In 2024, the Supreme Court issued the first convictions from the latter ruling.[371]

Law, corruption and crime

[edit]Post-Soviet Russia under the regime of Vladimir Putin has been governed by a form of crony capitalism.[372][373] Its political system has been variously described as a kleptocracy,[374] an oligarchy,[375] and a plutocracy.[372] As of 2024[update], it is the lowest rated European country in Transparency International's annual Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 154th out of the 180 countries listed.[376]

Corruption has significantly increased following the collapse of the Soviet Union,[377] and is seen as a significant issue in society.[378][379] It affects various sectors, including the economy,[378] the government,[377] law enforcement,[380] healthcare,[381][382] education,[383] and the military.[384] Russia's shadow economy was estimated to be about 44% of the total GDP in 2018.[385] Penal military units have been deployed as storm troops during the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War since 2022, such as the Storm-Z and Storm-V units.[386][387] According to estimates by the BBC, around 48,000 prisoners were recruited to fight for the Wagner Group.[388]

The primary and fundamental statement of laws in Russia is the constitution. Statutes, such as the Russian Civil Code and the Russian Criminal Code, are the predominant legal sources of Russian law.[389][390] Russia has the largest incarcerated population in Europe, and the fifth-largest incarcerated population in the world.[391] Its incarceration rate is among the highest in Europe,[392] although the number has fallen steadily, by 59% since 2000.[391] As of 2021[update], Russia's intentional homicide rate stood at 6.8 per 100,000 people.[393] In 2023, Russia had the world's second-largest illegal arms trade market, after the United States, was described as a key hub for human trafficking, and was ranked first in Europe and 19th globally in the Global Organized Crime Index.[394]

Economy

[edit]Russia has a high-income,[395] industrialized,[396] mixed market-oriented economy following a turbulent transition from the Soviet planned model during the 1990s.[397][398][399][400] It has the eleventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and the fourth-largest economy by GDP (PPP). As of 2023[update], the service sector accounts for roughly 57% of total GDP, followed by the industrial sector (30%), while the agricultural sector is the smallest, at 3% of total GDP.[6] Russia's foreign exchange reserves are the fifth-largest in the world.[401] It has a labour force of about 73 million, which is the eighth-largest in the world.[402] As of 2023[update], Russia's largest trading partner by total import and export volume is China.[403]

Russia's human development is ranked as "very high" in the annual Human Development Index.[405] Roughly 70% of Russia's total GDP is driven by domestic consumption,[406][clarification needed]and the country has the world's twelfth-largest consumer market.[407] Russia has the fifth-highest number of billionaires in the world.[408] However, its income inequality remains comparatively high compared to other developed countries.[409] The variance of natural resources among its federal subjects has also led to regional economic disparities.[410][411] High levels of corruption,[412] a shrinking labor force,[413] a brain drain problem[414] and an aging and declining population also remain major barriers to future economic growth.[415][416]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the country has faced extensive sanctions and other negative financial actions from the Western world and its allies which have the aim of isolating the Russian economy from the Western financial system.[213] However, Russia has completed its transition into a war economy,[417] and has shown resilience to such measures broadly, maintaining economic stability and growth—driven primarily by high military expenditure,[418] rising household consumption and wages,[419] low unemployment,[420] and increased government spending.[421] Yet, inflation has remained comparatively high,[422] with experts predicting the sanctions will have a long-term negative effect on the Russian economy.[423]

Transport and energy

[edit]Railway transport in Russia is mostly controlled by the state-run Russian Railways. The total length of common-used railway tracks is the world's third-longest, exceeding 87,000 km (54,100 mi).[424] As of 2019[update], Russia has the world's fifth-largest road network, with over 1.5 million km of roads.[425] However, its road density is among the world's lowest, in part to its vast land area.[426] Russia's inland waterways are the longest in the world, totaling 102,000 km (63,380 mi).[427] It has over 900 airports,[428] ranking seventh in the world, of which the busiest is Sheremetyevo International Airport in Moscow. The largest ports include the Port of Novorossiysk, the Great Port of Saint Petersburg and the Port of Vladivostok.[429]

Russia has one of the world's largest amounts of energy resources throughout its vast landmass, particularly natural gas and oil, which play a crucial role in its energy self-sufficiency and exports.[397] It has been widely described as an energy superpower.[431] Russia has the world's largest proven gas reserves,[432] the second-largest coal reserves,[433] the eighth-largest proven oil reserves,[434] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[435] As of 2023[update], it is also the second-largest producer[436] and the third-largest exporter of natural gas,[437] as well as the second-largest producer and exporter of crude oil.[438] Russia's large oil and gas sector accounted for 30% of its federal budget revenues in 2024, down from 50% in the mid-2010s, suggesting economic diversification.[439]

Russia is the world's third-largest energy producer as of 2023[update].[440] Fossil fuels account for over 64% of energy production and 87% of energy consumption.[441] Natural gas is by far the largest source of energy, comprising over half of the energy production and 42% of electricity consumption.[441] Russia was the first country to develop civilian nuclear power, building the world's first nuclear power plant in 1954, and remains a pioneer in nuclear energy technology and is considered a world leader in fast neutron reactors.[442] Russia is the world's fourth-largest nuclear energy producer. Russian energy policy aims to expand the role of nuclear energy and develop new reactor technology.[442] Russia is the sole country that builds and operates nuclear-powered icebreakers,[443] which ease navigation along the Northern Sea Route,[443]: 192 and aid in utilizing its Arctic policy in its continental shelf.[444]

Russia joined the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015, and ratified the agreement in 2019.[445] Its greenhouse gas emissions are the fourth-largest in the world as of 2023[update].[446] Coal accounts for over 10% of its energy consumption.[441] Russia is the fifth-largest hydroelectric producer as of 2022[update],[447] with hydroelectric power contributing almost a fifth to the total energy generation (17%).[441] Though it is the eighth-largest renewable energy producer as of 2023[update], the use and development of other renewable energy resources remain negligible,[441] as Russia is among the few countries without strong governmental or public support for a renewable energy transition.[448]

Agriculture and fishery

[edit]

Agriculture, forestry and fishing contributes about 3.3% of the country's total GDP as of 2023[update].[449] It has the world's fourth-largest cultivated area, at 1,265,267 square kilometres (488,522 sq mi). However, due to the harshness of its environment, only about 13.1% of its land is agricultural,[6] with an additional 7.4% being arable.[450] The country's agricultural land is considered part of the "breadbasket" of Europe.[451] More than one-third of the sown area is devoted to fodder crops, and the remaining farmland is used industrial crops, vegetables, and fruits.[452] The main product of Russian farming has always been grain, which occupies well over half the cropland.[452] Russia is the world's largest exporter of wheat and the largest producer of barley and buckwheat.[403][453] It is also among the largest exporters of maize and sunflower oil, as well as the leading producer of fertiliser.[453][403]

Various analysts of climate change adaptation foresee large opportunities for Russian agriculture during the rest of the 21st century as arability increases in Siberia, which would lead to both internal and external migration to the region.[454] Owing to its large coastline along three oceans and twelve marginal seas, Russia maintains the world's sixth-largest fishing industry, capturing nearly 5 million tons of fish in 2018.[455] It is home to the world's finest caviar, the beluga, and produces about one-third of all canned fish and some one-fourth of the world's total fresh and frozen fish.[452]

Science and technology

[edit]Russia spent about 1% of its GDP on research and development in 2019, with the world's tenth-highest budget.[456] It also ranked tenth worldwide in the number of scientific publications in 2020, with roughly 1.3 million papers.[457] Since 1904, Nobel Prize were awarded to 26 Soviets and Russians in physics, chemistry, medicine, economy, literature and peace.[458] Russia ranked 60th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024, down from 45th in 2021.[459][460]

Since the times of Nikolay Lobachevsky, who pioneered the non-Euclidean geometry, and Pafnuty Chebyshev, a prominent tutor, Russian mathematicians became among the world's most influential.[461] Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of modern chemistry.[462] Nine Soviet and Russian mathematicians have been awarded with the Fields Medal. Grigori Perelman was offered the first ever Clay Millennium Prize Problems Award for his final proof of the Poincaré conjecture in 2002, as well as the Fields Medal in 2006.[463]

Alexander Popov was among the inventors of radio,[464] while Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov were co-inventors of laser and maser.[465] Oleg Losev made crucial contributions in the field of semiconductor junctions, and discovered light-emitting diodes.[466] Vladimir Vernadsky is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and radiogeology.[467] Élie Metchnikoff is known for his groundbreaking research in immunology.[468] Ivan Pavlov is known chiefly for his work in classical conditioning.[469] Lev Landau made fundamental contributions to many areas of theoretical physics.[470]

Nikolai Vavilov was best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants.[471] Trofim Lysenko was known mainly for Lysenkoism.[472] Many famous Russian scientists and inventors were émigrés. Igor Sikorsky was an aviation pioneer.[473] Vladimir Zworykin was the inventor of the iconoscope and kinescope television systems.[474] Theodosius Dobzhansky was the central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the modern synthesis.[475] George Gamow was one of the foremost advocates of the Big Bang theory.[476]

Space exploration

[edit]

Roscosmos is Russia's national space agency. The country's achievements in the field of space technology and space exploration can be traced back to Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the father of theoretical astronautics, whose works had inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers, such as Sergey Korolyov, Valentin Glushko, and many others who contributed to the success of the Soviet space programme in the early stages of the Space Race and beyond.[477]: 6–7, 333

In 1957, the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, was launched. In 1961, the first human trip into space was successfully made by Yuri Gagarin. Many other Soviet and Russian space exploration records ensued. In 1963, Valentina Tereshkova became the first and youngest woman in space, having flown a solo mission on Vostok 6.[478] In 1965, Alexei Leonov became the first human to conduct a spacewalk, exiting the space capsule during Voskhod 2.[479]

In 1957, Laika, a Soviet space dog, became the first animal to orbit the Earth, aboard Sputnik 2.[480] In 1966, Luna 9 became the first spacecraft to achieve a survivable landing on a celestial body, the Moon.[481] In 1968, Zond 5 brought the first Earthlings (two tortoises and other life forms) to circumnavigate the Moon.[482] In 1970, Venera 7 became the first spacecraft to land on another planet, Venus.[483] In 1971, Mars 3 became the first spacecraft to land on Mars.[484]: 34–60 During the same period, Lunokhod 1 became the first space exploration rover,[485] while Salyut 1 became the world's first space station.[486]

As of 2023[update], Russia has 181 active satellites in space, which is the third-highest in the world.[487] Between the final flight of the Space Shuttle programme in 2011 and the 2020 SpaceX's first crewed mission, Soyuz rockets were the only launch vehicles capable of transporting astronauts to the ISS.[488] Luna 25 launched in August 2023, was the first of the Luna-Glob Moon exploration programme.[489]

Tourism

[edit]

Most foreign tourists come from China.[490] Major tourist routes in Russia include a journey around the Golden Ring of Russia, a theme route of ancient Russian cities; cruises on large rivers such as the Volga; hikes on mountain ranges such as the Caucasus Mountains,[491] and journeys on the famous Trans-Siberian Railway.[492] Russia's most visited and popular landmarks include Red Square, the Peterhof Palace, the Kazan Kremlin, the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius and Lake Baikal.[493]

Moscow, the nation's cosmopolitan capital and historic core, is a bustling modern megacity; it retains classical and Soviet-era architecture while boasting high art, world class ballet, and modern skyscrapers.[494] Saint Petersburg, the imperial capital, is famous for its classical architecture, cathedrals, museums and theatres, white nights, crisscrossing rivers and numerous canals.[495] Russia is famed worldwide for its rich museums, such as the State Russian, the State Hermitage, and the Tretyakov Gallery, and for theatres such as the Bolshoi and the Mariinsky. The Moscow Kremlin and the Saint Basil's Cathedral are among the cultural landmarks of Russia.[496]

Demographics

[edit]Russia had an estimated population of 146.0 million in 2025 (143.6 million excluding Crimea and Sevastopol),[14] down from 147.2 million in the 2021 census.[497] It is the most populous country in Europe and ninth-most populous country in the world. With a population density of 8.5 inhabitants per square kilometre (22 inhabitants/sq mi),[498] Russia is one of the world's most sparsely populated countries,[6] with the vast majority of its people concentrated within its western part.[499] The country is highly urbanised, with two-thirds of the population living in urban areas. As of 2024[update], the total fertility rate across Russia is estimated to be 1.41 children born per woman,[500] which is below the replacement rate of 2.1 and among the lowest in the world.[501] Subsequently, it has one of the oldest populations in the world, with a median age of 41.9 years.[6]

Russia's population peaked at over 148 million in 1993, having subsequently declined due to its death rate exceeding its birth rate, which some analysts have called a demographic crisis.[502] In 2009, it recorded annual population growth for the first time in fifteen years, and subsequently experienced annual population growth due to declining death rates, increased birth rates, and increased immigration.[503] However, these population gains have been reversed since 2020, as excessive deaths from the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the largest peacetime decline in its history.[504] Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the demographic crisis has deepened,[505] owing to high military fatalities[506] and renewed emigration.[507] Recent studies have shown that between 15-45% of Russian emigrants have returned to Russia, though these numbers are not conclusive.[508]

Russia is a multinational state with many subnational entities associated with different minorities.[509] There are over 193 ethnic groups nationwide. In the 2010 census, roughly 81% of the population were ethnic Russians, and the remaining 19% of the population were ethnic minorities.[510] Over four-fifths of Russia's population was of European descent—of whom the vast majority were Slavs,[509][511] with a substantial minority of Finno-Ugric and Germanic peoples.[512][513] Russia has the third-largest immigrant population in the world, with over 12 million immigrants residing in the country as of 2019[update].[514] The vast majority of the Immigrants hail from post-Soviet states, with about half of them being from Ukraine and Kazakhstan as of 2020[update].[515]

| Rank | Name | Federal subject | Pop. | Rank | Name | Federal subject | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moscow | Moscow | 13,274,285 | 11 | Samara | Samara Oblast | 1,154,223 | ||

| 2 | Saint Petersburg | Saint Petersburg | 5,652,922 | 12 | Rostov-on-Don | Rostov Oblast | 1,143,123 | ||

| 3 | Novosibirsk | Novosibirsk Oblast | 1,637,266 | 13 | Omsk | Omsk Oblast | 1,101,367 | ||

| 4 | Yekaterinburg | Sverdlovsk Oblast | 1,548,187 | 14 | Voronezh | Voronezh Oblast | 1,041,722 | ||

| 5 | Kazan | Tatarstan | 1,329,825 | 15 | Perm | Perm Krai | 1,027,518 | ||

| 6 | Krasnoyarsk | Krasnoyarsk Krai | 1,211,756 | 16 | Volgograd | Volgograd Oblast | 1,012,219 | ||

| 7 | Nizhny Novgorod | Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 1,198,245 | 17 | Saratov | Saratov Oblast | 886,165 | ||

| 8 | Chelyabinsk | Chelyabinsk Oblast | 1,176,770 | 18 | Tyumen | Tyumen Oblast | 872,077 | ||

| 9 | Ufa | Bashkortostan | 1,166,098 | 19 | Tolyatti | Samara Oblast | 662,683 | ||

| 10 | Krasnodar | Krasnodar Krai | 1,154,885 | 20 | Makhachkala | Dagestan | 625,322 | ||

Language

[edit]Russian is the official and the predominantly spoken language in Russia.[3] It is the most spoken native language in Europe, the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia, as well as the world's most widely spoken Slavic language.[518] Russian is one of two official languages aboard the International Space Station,[519] as well as one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[518]

Russia is a multilingual nation: approximately 100–150 minority languages are spoken across the country.[520][521] According to the Russian Census of 2010, 137.5 million across the country spoke Russian, 3.1 million spoke Tatar, and 1.1 million spoke Ukrainian.[522] The constitution gives the country's individual republics the right to establish their own state languages in addition to Russian, as well as guarantee its citizens the right to preserve their native language and to create conditions for its study and development.[523] However, various experts have claimed Russia's linguistic diversity is rapidly declining due to many languages becoming endangered.[524][525]

Religion

[edit]

Russia is constitutionally a secular state that officially enshrines freedom of religion.[526][527] The largest religion is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, chiefly represented by the Russian Orthodox Church,[526][528] which is legally recognised for its "special role" in the country's "history and the formation and development of its spirituality and culture."[527] Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism are recognised by Russian law as the "traditional" religions of the country constituting its "historical heritage".[529][530]