Russians

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

русские | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 135 million [citation needed] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diaspora | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | approx. 7,500,000 (including Russian Jews and Russian Germans)[2][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ukraine | 7,170,000 (2018) (including Crimea)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States | 3,072,756 (2009) (including Russian Jews and Russian Germans)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kazakhstan | 2,983,317 (2024 government est.)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uzbekistan | 720,324 (2019)[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Belarus | 706,992 (2019)[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canada | 622,445 (2016) (Russian ancestry, excluding Russian Germans)[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian (Russian Sign Language) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predominantly Eastern Orthodoxy (Russian Orthodoxy), minority irreligion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other East Slavs (Belarusians, Ukrainians, Rusyns)[46] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Russians (Russian: русские, romanized: russkiye [ˈruskʲɪje] ⓘ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian, the most spoken Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Orthodox Christianity, ever since the Middle Ages. By total numbers, they compose the largest Slavic and European nation.[47]

Genetic studies show that Russians are closely related to Poles, Belarusians, Ukrainians, as well as Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Finns.[46][48][49][50] They were formed from East Slavic tribes, and their cultural ancestry is based in Kievan Rus'. The Russian word for the Russians is derived from the people of Rus' and the territory of Rus'. Russians share many historical and cultural traits with other European peoples, and especially with other East Slavic ethnic groups, specifically Belarusians and Ukrainians.

The vast majority of Russians live in native Russia,[47] but notable minorities are scattered throughout other post-Soviet states such as Belarus, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Ukraine, and the Baltic states. A large Russian diaspora (sometimes including Russian-speaking non-Russians), estimated at 25 million people,[51] has developed all over the world, with notable numbers in the United States, Germany, Brazil, and Canada.

Ethnonym

[edit]There are two Russian words which are commonly translated into English as "Russians". One is русские (russkiye), which in modern Russia most often means "ethnic Russians". The other one is россияне (rossiyane), derived from Россия (Rossiya, Russia), which denotes "people of Russia", regardless of ethnicity or religious affiliation.[52] In daily usage, those terms are often mixed up, and since Vladimir Putin became president, the ethnic term русские has supplanted the non-ethnic term.[53]: 26

The name of the Russians derives from the early medieval Rus' people, a group of Norse merchants and warriors who relocated from across the Baltic Sea and played an important part in the foundation of the first East Slavic state that later became the Kievan Rus'.[54][55]

The idea of a single "all-Russian nation" encompassing the East Slavic peoples, or a "triune nation" of three brotherly "Great Russian", "Little Russian" (i.e. Ukrainian), and "White Russian" (i.e. Belarusian) peoples became the official doctrine of the Russian Empire from the beginning of the 19th century onwards.[53]: 25–26

History

[edit]Ancient history

[edit]

The ancestors of modern Russians are the Slavic tribes, whose original home is thought by some scholars to have been the wooded areas of the Pinsk Marshes, one of the largest wetlands in Europe.[56] The East Slavs gradually settled Western Russia with Moscow included in two waves: one moving from Kiev toward present-day Suzdal and Murom and another from Polotsk toward Novgorod and Rostov.[57] Prior to the Slavic migration in the 6-7th centuries, the Suzdal-Murom and Novgorod-Rostov areas were populated by Finnic peoples,[58] including the Merya,[59] the Muromians,[60] and the Meshchera.[61]

From the 7th century onwards, the East Slavs slowly assimilated the native Finnic peoples,[62] so that by year 1100, the majority of the population in Western Russia was Slavic-speaking.[57][58] Recent genetic studies confirm the presence of a Finnic substrate in modern Russian population.[63]

Outside archaeological remains, little is known about the predecessors to Russians in general prior to 859 AD, when the Primary Chronicle starts its records.[64] By 600 AD, the Slavs are believed to have split linguistically into southern, western, and eastern branches.[citation needed]

Medieval history

[edit]

The Rus' state was established in northern Russia in the year 862,[65] which was ruled by the Varangians.[66][67] Staraya Ladoga and Novgorod became the first major cities of the new union of immigrants from Scandinavia with the Slavs and Finns.[68] In 882, the prince Oleg seized Kiev, thereby uniting the northern and southern lands of the East Slavs under one authority.[66] The state adopted Christianity from the Byzantine Empire in 988. Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state as a result of in-fighting between members of the princely family that ruled it collectively.[69]

After the 13th century, Moscow became a political and cultural center. Moscow has become a center for the unification of Russian lands.[70] By the end of the 15th century, Moscow united the northeastern and northwestern Russian principalities, overthrew the "Mongol yoke" in 1480,[71] and would be transformed into the Tsardom of Russia after Ivan IV was crowned tsar in 1547.[72]

Modern history

[edit]

In 1721, Tsar Peter the Great renamed his state as the Russian Empire, hoping to associate it with historical and cultural achievements of ancient Rus' – in contrast to his policies oriented towards Western Europe. The state now extended from the eastern borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to the Pacific Ocean, and became a great power; and one of the most powerful states in Europe after the victory over Napoleon. Peasant revolts were common, and all were fiercely suppressed. The Emperor Alexander II abolished Russian serfdom in 1861, but the peasants fared poorly and revolutionary pressures grew. In the following decades, reform efforts such as the Stolypin reforms of 1906–1914, the constitution of 1906, and the State Duma (1906–1917) attempted to open and liberalize the economy and political system, but the Emperors refused to relinquish autocratic rule and resisted sharing their power.

A combination of economic breakdown, war-weariness, and discontent with the autocratic system of government triggered revolution in Russia in 1917. The overthrow of the monarchy initially brought into office a coalition of liberals and moderate socialists, but their failed policies led to seizure of power by the communist Bolsheviks on 25 October 1917 (7 November New Style). In 1922, Soviet Russia, along with Soviet Ukraine, Soviet Belarus, and the Transcaucasian SFSR signed the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR, officially merging all four republics to form the Soviet Union as a country. Between 1922 and 1991, the history of Russia became essentially the history of the Soviet Union, effectively an ideologically based state roughly conterminous with the Russian Empire before the 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. From its first years, government in the Soviet Union based itself on the one-party rule of the Communists, as the Bolsheviks called themselves, beginning in March 1918. The approach to the building of socialism, however, varied over different periods in Soviet history: from the mixed economy and diverse society and culture of the 1920s through the command economy and repressions of the Joseph Stalin era to the "era of stagnation" from the 1960s to the 1980s. The actions of the Soviet government caused the death of millions of citizens in the famine of 1930–1933 and the Great Purge. The attack by Nazi Germany and the ensuing war, together with the Holocaust, again claimed millions of lives. Millions of Russian civilians and prisoners of war were killed or starved to death during Nazi Germany's genocidal policies called the Hunger Plan and the Generalplan Ost, including one million civilian casualties during the Siege of Leningrad. After the victory of the Soviet Union and the Western Allies, the Soviet Union became a superpower opposing Western countries during the Cold War.

By the mid-1980s, with Soviet economic and political weaknesses becoming acute, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev embarked on major reforms; these culminated in the dissolution of the Soviet Union, leaving Russia again alone and marking the beginning of the post-Soviet Russian period. The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic renamed itself the Russian Federation and became the successor state to the Soviet Union. One of the negative consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union was the problem of discrimination against the 25 million ethnic Russians living in a number of post-Soviet states.[74]

Geographic distribution

[edit]

Ethnic Russians historically migrated within the areas of the former Russian Empire and Soviet Union, though they were sometimes encouraged to re-settle in borderland areas by the Tsarist and later Soviet government.[75] Sometimes ethnic Russian communities, such as the Lipovans who settled in the Danube delta or the Doukhobors in Canada, emigrated as religious dissidents fleeing the central authority.[76]

There are also small Russian communities in the Balkans — including Lipovans in the Danube delta[77] — Central European nations such as Germany and Poland, as well as Russians settled in China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Australia. These communities identify themselves to varying degrees as Russians, citizens of these countries, or both.[citation needed]

Significant numbers of Russians emigrated to Canada, Australia and the United States. Brighton Beach, Brooklyn and South Beach, Staten Island in New York City are examples of large communities of recent Russian and Russian-Jewish immigrants. Other examples are Sunny Isles Beach, a northern suburb of Miami, and West Hollywood of the Los Angeles area.[citation needed]

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, many Russians who were identified with the White army moved to China — most of them settling in Harbin and Shanghai.[78] By the 1930s, Harbin had 100,000 Russians. Many of these Russians moved back to the Soviet Union after World War II. Today, a large group in northern China still speak Russian as a second language. Russians (eluosizu) are one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China (as the Russ); there are approximately 15,600 Russian Chinese living mostly in northern Xinjiang, and also in Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang.[citation needed]

According to the 2021 Russian census, the number of ethnic Russians in the Russian Federation decreased by nearly 5.43 million, from roughly 111 million people in 2010 to approximately 105.5 million in 2021.[79]

Ethnographic groups

[edit]

Among Russians, a number of ethnographic groups stand out, such as: the Northern Russians, the Southern Russians, the Cossacks, the Goryuns, the Kamchadals, the Polekhs, the Pomors, the Russian Chinese, the Siberians (Siberiaks), Starozhily, some groupings of Old Believers (Kamenschiks, Lipovans, Semeiskie), and others.[80]

The main ones are the Northern and Southern Russian groups. At the same time, the proposal of the ethnographer Dmitry Zelenin in his major work of 1927 Russian (East Slavic) Ethnography to consider them as separate East Slavic peoples[81] did not find support in scientific circles.[82]

Russia's Arctic coastline had been explored and settled by Pomors, Russian settlers from Novgorod.[83]

Cossacks inhabited sparsely populated areas in the Don, Terek, and Ural river basins, and played an important role in the historical and cultural development of parts of Russia.[84]

Genetics

[edit]In accordance with the 2008 research results of Russian and Estonian geneticists, two groups of Russians are distinguished: the northern and southern populations.[49][85]

Central and Southern Russians, to which the majority of Russian populations belong, according to Y chromosome R1a, are included in the general "East European" gene cluster with the rest East and West Slavs (Poles, Czechs and Slovaks), as well as the non-Slavic Hungarians and Aromanians.[48][49][50] Genetically, East Slavs are quite similar to West Slavs; such genetic similarity is somewhat unusual for genetics with such a wide settlement of the Slavs, especially Russians.[86] The high unity of the autosomal markers of the East Slavic populations and their significant differences from the neighboring Finnic, Turkic and Caucasian peoples were revealed.[49][48]

Northern Russians, according to mtDNA, Y chromosome and autosomal marker CCR5de132, are included in the "North European" gene cluster (the Poles, the Balts, Germanic and Baltic Finnic peoples).[49][87]

Consequently, the already existing biologo-genetic studies have made all hypotheses about the mixing of the Russians with non-Slavic ethnic groups or their "non-Slavism" obsolete or pseudoscientific. At the same time, the long-standing identification of the Northern Russian and Southern Russian ethnographic groups by ethnologists was confirmed. The previous conclusions of physical anthropologists,[88] historians and linguists (see, in particular, the works of the academician Valentin Yanin) about the proximity of the ancient Novgorod Slavs and their language not to the East, but to west Baltic Slavs. As can be seen from genetic resources, the contemporary Northern Russians also are genetically close of all Slavic peoples only to the Poles and similar to the Balts. However, this does not mean the northern Russians origin from the Balts or the Poles, more likely, that all the peoples of the Nordic gene pool are descendants of Paleo-European population, which has remained around Baltic Sea.[49][87]

At the same time, according to other scholars, the Russians have close genetic affinities to surrounding Northeast and Eastern European populations. They also display evidence for multiple genetic ancestries and admixture events, and high identity-by-descent sharing with the Finnic peoples.[89]

While modern European populations derive most of their ancestry from three major sources: Western hunter-gatherers, Early European Farmers, and Western Steppe Herders (Yamnaya), this three-way model is insufficient to explain the ethnogenesis of northeastern Europeans such as Saami, Russians, Mordovians, Chuvash, Estonians, Hungarians, and Finns. They carry an additional Siberian/Nganasan-related genetic component and increased allele sharing with modern East Asians.[90][91]

The most common human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup is haplogroup R1a (c. 46,7%), followed by haplogroup N-M231 (c. 21,6%), haplogroup I-M170 (c. 17,6%), and haplogroup R1b (c. 5,8%). The remainder (c. 8,3%) are other less frequent haplogroups (E3b, J2, etc.).[92]

Assimilation and immigration

[edit]Russians have sometimes found it useful to emphasize their self-perceived ability to assimilate other people to the Russian ethnicity - and as a historic great power with imperial expansionist tendencies the Russian state has sometimes encouraged Russian-centred monoculturalism. Steppe peoples, Tatars, Baltic Germans, Lithuanians and native Siberians in Rus', Muscovy or the Russian Empire could in theory become "Russians" (Russian: русские) simply by accepting Russian Orthodoxy as their faith.[93][94] The attitude of ready inclusivity is summed up in the popular phrase (sometimes attributed to Emperor Alexander III of Russia) - Хочешь быть русским - будь им! (transl. You want to be Russian - be that!).[95]

Language

[edit]Russian is the official and the predominantly spoken language in Russia.[96] It is the most-spoken native language in Europe,[97] the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia,[98] as well as the world's most widely spoken Slavic language.[98] Russian is the third-most used language on the Internet after English and Spanish,[99] and is one of two official languages aboard the International Space Station,[100] as well as one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[101]

Culture

[edit]Literature

[edit]

Russian literature is considered to be among the world's most influential and developed.[102] It can be traced to the Middle Ages, when epics and chronicles in vernacular Old East Slavic were composed.[102][103] By the Age of Enlightenment, literature had grown in importance, with works from Mikhail Lomonosov, Denis Fonvizin, Gavrila Derzhavin, and the Sentimentalist Nikolay Karamzin.[104] From the early 1830s, during the Golden Age of Russian Poetry, literature underwent an astounding golden age in poetry, prose and drama.[105] Romantic literature permitted a flowering of poetic talent: Vasily Zhukovsky and later his protégé Alexander Pushkin came to the fore.[106] Following Pushkin's footsteps, a new generation of poets were born, including Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolay Nekrasov, Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Fyodor Tyutchev and Afanasy Fet.[104]

The first great Russian novelist was Nikolai Gogol.[107][104] Then, during the Age of Realism, came Ivan Turgenev, who mastered both short stories and novels.[108] Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy soon became internationally renowned.[104] Ivan Goncharov is remembered mainly for his novel Oblomov.[109] Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin wrote prose satire,[104][110] while Nikolai Leskov is best remembered for his shorter fiction.[104][111] In the second half of the century Anton Chekhov excelled in short stories and became a leading dramatist.[104][112] Other important 19th-century developments included the fabulist Ivan Krylov,[113] non-fiction writers such as the critic Vissarion Belinsky,[104][114] and playwrights such as Aleksandr Griboyedov and Aleksandr Ostrovsky.[115][116] The beginning of the 20th century ranks as the Silver Age of Russian Poetry. This era had poets such as Alexander Blok, Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, Konstantin Balmont,[117] Marina Tsvetaeva, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Osip Mandelstam.[104] It also produced some first-rate novelists and short-story writers, such as Aleksandr Kuprin, Nobel Prize winner Ivan Bunin, Leonid Andreyev, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Andrei Bely.[104]

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian literature split into Soviet and white émigré parts. In the 1930s, Socialist realism became the predominant trend in Russia. Its leading figure was Maxim Gorky, who laid the foundations of this style.[118] Mikhail Bulgakov was one of the leading writers of the Soviet era.[119] Nikolay Ostrovsky's novel How the Steel Was Tempered has been among the most successful works of Russian literature. Influential émigré writers include Vladimir Nabokov.[120] Some writers dared to oppose Soviet ideology, such as Nobel Prize-winning novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who wrote about life in the Gulag camps.[104][121]

During the post-Soviet 1990s writers are already not recognised as very special guides by most Russians.[104] At the beginning of the 21st century, the most discussed figures, postmodernists Victor Pelevin and Vladimir Sorokin remained the leading Russian writers.[122]

Philosophy

[edit]Russian philosophy has been greatly influential. Religious and spiritual philosophy is represented by works of Vladimir Solovyov, Nikolai Berdyaev, Pavel Florensky, Semyon Frank, Nikolay Lossky, Vasily Rozanov, and others.[123] Helena Blavatsky gained international following as the leading theoretician of Theosophy, and co-founded the Theosophical Society.[124]

Social and political philosophy is also remarkable. Alexander Herzen is known as one of the fathers of agrarian populism.[125] Mikhail Bakunin is referred to as the father of anarchism.[126] Peter Kropotkin was the most important theorist of anarcho-communism.[127] Mikhail Bakhtin's writings have significantly inspired scholars.[128] Vladimir Lenin, a major revolutionary, developed a variant of communism known as Leninism. Leon Trotsky, on the other hand, founded Trotskyism. Alexander Zinoviev was a prominent philosopher and writer in the second half of the 20th century.[129] Aleksandr Dugin, known for his fascist views, has been regarded as the "guru of geopolitics".[130]

Science

[edit]

Mikhail Lomonosov proposed the conservation of mass in chemical reactions, discovered the atmosphere of Venus, and founded modern geology.[131] Since the times of Nikolay Lobachevsky, who pioneered the non-Euclidean geometry, and a prominent tutor Pafnuty Chebyshev, Russian mathematicians became among the world's most influential.[132] Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of modern chemistry.[133] Sofya Kovalevskaya was a pioneer among women in mathematics in the 19th century.[134] Grigori Perelman was offered the first ever Clay Millennium Prize Problems Award for his final proof of the Poincaré conjecture in 2002, as well as the Fields Medal in 2006, both of which he declined.[135][136]

Alexander Popov was among the inventors of radio,[137] while Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov were co-inventors of laser and maser.[138] Zhores Alferov contributed significantly to the creation of modern heterostructure physics and electronics.[139] Oleg Losev made crucial contributions in the field of semiconductor junctions, and discovered light-emitting diodes.[140] Vladimir Vernadsky is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and radiogeology.[141] Élie Metchnikoff is known for his groundbreaking research in immunology.[142] Ivan Pavlov is known chiefly for his work in classical conditioning.[143] Lev Landau made fundamental contributions to many areas of theoretical physics.[144]

Nikolai Vavilov was best known for having identified the centers of origin of cultivated plants.[145] Many famous Russian scientists and inventors were émigrés. Igor Sikorsky was an aviation pioneer.[146] Vladimir Zworykin was the inventor of the iconoscope and kinescope television systems.[147] Theodosius Dobzhansky was the central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the modern synthesis.[148] George Gamow was one of the foremost advocates of the Big Bang theory.[149] Konstantin Tsiolkovsky is called the father of theoretical astronautics, whose works had inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers, such as Valentin Glushko, and many others.[150]: 6–7, 333

In 1961, the first human trip into space was successfully made by Yuri Gagarin. In 1963, Valentina Tereshkova became the first and youngest woman in space, having flown a solo mission on Vostok 6.[151] In 1965, Alexei Leonov became the first human to conduct a spacewalk, exiting the space capsule during Voskhod 2.[152]

Painting

[edit]

Early Russian painting is represented in icons and vibrant frescos. In the early 15th century, the master icon painter Andrei Rublev created some of Russia's most treasured religious art.[153] The Russian Academy of Arts, which was established in 1757, to train Russian artists, brought Western techniques of secular painting to Russia.[154] In the 18th century, academicians Ivan Argunov, Dmitry Levitzky, Vladimir Borovikovsky became influential.[155] The early 19th century saw many prominent paintings by Karl Briullov and Alexander Ivanov, both of whom were known for Romantic historical canvases.[156][157] Ivan Aivazovsky, another Romantic painter, is considered one of the greatest masters of marine art.[158]

In the 1860s, a group of critical realists (Peredvizhniki), led by Ivan Kramskoy, Ilya Repin and Vasiliy Perov broke with the academy, and portrayed the many-sided aspects of social life in paintings.[159][160] The turn of the 20th century saw the rise of symbolism; represented by Mikhail Vrubel and Nicholas Roerich.[161][162] The Russian avant-garde flourished from approximately 1890 to 1930; and globally influential artists from this era were El Lissitzky,[163] Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marc Chagall.[164]

Music

[edit]

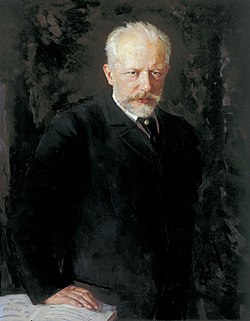

Until the 18th century, music in Russia consisted mainly of church music and folk songs and dances.[165] In the 19th century, it was defined by the tension between classical composer Mikhail Glinka along with other members of The Mighty Handful, and the Russian Musical Society led by composers Anton and Nikolay Rubinstein.[165] The later tradition of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era, was continued into the 20th century by Sergei Rachmaninoff, one of the last great champions of the Romantic style of European classical music.[166] World-renowned composers of the 20th century include Alexander Scriabin, Alexander Glazunov, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Georgy Sviridov and Alfred Schnittke.[165]

Soviet and Russian conservatories have turned out generations of world-renowned soloists. Among the best known are violinists David Oistrakh and Gidon Kremer,[167][168] cellist Mstislav Rostropovich,[169] pianists Vladimir Horowitz,[170] Sviatoslav Richter,[171] and Emil Gilels,[172] and vocalist Galina Vishnevskaya.[173]

During the Soviet times, popular music also produced a number of renowned figures, such as the two balladeers—Vladimir Vysotsky and Bulat Okudzhava,[174] and performers such as Alla Pugacheva.[175] Jazz, even with sanctions from Soviet authorities, flourished and evolved into one of the country's most popular musical forms.[174] The Ganelin Trio have been described by critics as the greatest ensemble of free-jazz in continental Europe.[176] By the 1980s, rock music became popular across Russia, and produced bands such as Aria, Aquarium,[177] DDT,[178] and Kino.[179][180] Pop music in Russia has continued to flourish since the 1960s, with globally famous acts such as t.A.T.u.[181] In the recent times, Little Big, a rave band, has gained popularity in Russia and across Europe.[182]

Cinema

[edit]

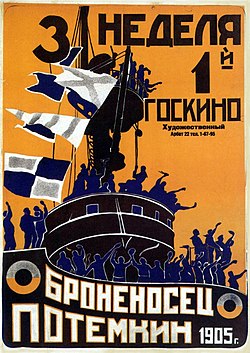

Russian and later Soviet cinema was a hotbed of invention, resulting in world-renowned films such as The Battleship Potemkin.[184] Soviet-era filmmakers, most notably Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky, would go on to become among of the world's most innovative and influential directors.[185][186] Eisenstein was a student of Lev Kuleshov, who developed the groundbreaking Soviet montage theory of film editing at the world's first film school, the All-Union Institute of Cinematography.[187] Dziga Vertov's "Kino-Eye" theory had a huge impact on the development of documentary filmmaking and cinema realism.[188] Many Soviet socialist realism films were artistically successful, including Chapaev, The Cranes Are Flying, and Ballad of a Soldier.[citation needed]

The 1960s and 1970s saw a greater variety of artistic styles in Soviet cinema. The comedies of Eldar Ryazanov and Leonid Gaidai of that time were immensely popular, with many of the catchphrases still in use today.[189][190] In 1961–68 Sergey Bondarchuk directed an Oscar-winning film adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's epic War and Peace, which was the most expensive film made in the Soviet Union.[191] In 1969, Vladimir Motyl's White Sun of the Desert was released, a very popular film in a genre of ostern; the film is traditionally watched by cosmonauts before any trip into space.[192] In 2002, Russian Ark was the first feature film ever to be shot in a single take.[193] Today, the Russian cinema industry continues to expand.[194]

Architecture

[edit]

The history of Russian architecture begins with early woodcraft buildings of ancient Slavs,[153][195] and the architecture of Kievan Rus'.[153][196] Following the Christianization of Kievan Rus', for several centuries it was influenced predominantly by the Byzantine Empire.[153][197] Due to Mongol occupation cut ties with the Byzantine Empire Russian architecture inreached some original innovations, among them the church altar screen dividing iconostasis.[153] Aristotle Fioravanti and other Italian architects brought Renaissance trends into Russia, especially in reconstruction of Kremlin.[153][198] The 16th century saw the development of the unique tent-like churches; and the onion dome design, which is a distinctive feature of Russian architecture.[199] In the 17th century, the "fiery style" of ornamentation flourished in Moscow and Yaroslavl, gradually paving the way for the Naryshkin baroque of the 1690s. After the reforms of Peter the Great, Russia's architecture became influenced by Western European styles.[153][200] The 18th-century taste for Rococo architecture led to the splendid works of Bartolomeo Rastrelli and his followers.[201] During the reign of Catherine the Great, Saint Petersburg was transformed into an outdoor museum of Neoclassical architecture.[202] During Alexander I's rule, Empire style became the de facto architectural style, and Nicholas I opened the gate of Eclecticism to Russia. The second half of the 19th-century was dominated by the Neo-Byzantine and Russian Revival style.[153] In early 20th-century, Russian neoclassical revival became a trend.[200] Prevalent styles of the late 20th-century were the Art Nouveau, Constructivism,[203] and Socialist Classicism.[204]

Religion

[edit]

Most religious Russians are Eastern Orthodox Christians.[205][206] According to differing sociological surveys on religious adherence, between 41% to over 80% of the total population of Russia adhere to the Russian Orthodox Church.[205][207][208][209]

Non-religious Russians may associate themselves with the Orthodox faith for cultural reasons. Some Russian people are Old Believers: a relatively small schismatic group of the Russian Orthodoxy that rejected the liturgical reforms introduced in the 17th century. Other schisms from Orthodoxy include Spiritual Christianity, namely Doukhobors which in the 18th century rejected secular government, the Russian Orthodox priests, icons, all church ritual, the Bible as the supreme source of divine revelation and the divinity of Jesus, and later emigrated into Canada. Another Spiritual Christian mivement were Molokans which formed in the 19th century and rejected Czar's divine right to rule, icons, the Trinity as outlined by the Nicene Creed, Orthodox fasts, military service, and practices including water baptism.[210]

Other world religions have negligible representation among ethnic Russians. The largest of these groups are Islam with over 100,000 followers from national minorities,[211] and Baptists with over 85,000 Russian adherents.[212] Others are mostly Pentecostals, Evangelicals, Seventh-day Adventists, Lutherans, The Salvation Army, and Jehovah's Witnesses.[213]

Since the fall of the Soviet Union various new religious movements have sprung up and gathered a following among ethnic Russians. The most prominent of these are Rodnovery, the revival of the Slavic native religion also common to other Slavic nations.[214]

Sports

[edit]Football is the most popular sport in Russia.[215] The Soviet Union national football team became the first European champions by winning Euro 1960,[216] and reached the finals of Euro 1988.[217] In 1956 and 1988, the Soviet Union won gold at the Olympic football tournament. Russian clubs CSKA Moscow and Zenit Saint Petersburg won the UEFA Cup in 2005 and 2008.[218][219] The Russian national football team reached the semi-finals of Euro 2008.[220] Russia was the host nation for the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup,[221] and the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[222]

Ice hockey is very popular in Russia.[223] The Soviet Union men's national ice hockey team dominated the sport internationally throughout its existence,[224] and the modern-day Russia men's national ice hockey team is among the most successful teams in the sport.[223] Bandy is Russia's national sport, and it has historically been the highest-achieving country in the sport.[225] The Russian national basketball team won the EuroBasket 2007,[226] and the Russian basketball club PBC CSKA Moscow is among the most successful European basketball teams. The annual Formula One Russian Grand Prix was held at the Sochi Autodrom in the Sochi Olympic Park.[227]

Russia is the leading nation in rhythmic gymnastics; and Russian synchronized swimming is considered to be the world's best.[228] Figure skating is another popular sport in Russia, especially pair skating and ice dancing.[229] Russia has produced a number of famous tennis players,[230] such as Maria Sharapova and Daniil Medvedev. Chess is also a widely popular pastime in the nation, with many of the world's top chess players being Russian for decades.[231] The 1980 Summer Olympic Games were held in Moscow,[232] and the 2014 Winter Olympics and the 2014 Winter Paralympics were hosted in Sochi.[233][234]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Migration und Integration" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Regarding Upcoming Conference on Status of Russian Language Abroad". Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Regarding Upcoming Conference on Status of Russian Language Abroad". Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ "Державна служба статистики України". Ukrstat.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "American FactFinder – Results". Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ https://stat.gov.kz/api/iblock/element/178068/file/en/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Permanent population by national and / Or ethnic group, urban / Rural place of residence". Archived from the original on 2 February 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ "National composition of the population. The Republic of Belarus statistical bulletin" (PDF). belstat.gov.by. Minsk. 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". statcan.gc.ca. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Social Statistics Department of Latvia. "Pastāvīgo iedzīvotāju etniskais sastāvs reģionos un republikas pilsētās gada sākumā". Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 December 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "La communauté russe en France est "éclectique"". Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "communauté russe en France" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Population by Sex, Ethnic Nationality and County, 1 January. Administrative Division as at 01.01.2018". Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "Los rusos en Argentina constituyen la mayor comunidad de Latinoamérica – Edición Impresa – Información General". Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Moldovan Population Census from 2014". Moldovan National Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Contra país estagnado, comunidade russa foge e se estabelece no Brasil". R7.com (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2025.

- ^ "Русские в Туркмении: люди второго сорта | Журнал РЕПИН.инфо". Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Gyventojų pagal tautybę dalis, palyginti su bendru nuolatinių gyventojų skaičiumi". osp.stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ "2006 census". Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan". azstat.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.

- ^ "Befolkning 31.12. Efter Område, Bakgrundsland, Kön, År och Uppgifter". Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año". INE. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ "МИД России | 12/02/2009 | Интервью Посла России в Турции В.Е.Ивановского, опубликованное в журнале "Консул" № 4 /19/, декабрь 2009 года". Mid.ru. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Türkiye'deki Rus Sayısı Belli Oldu. (Turkish)". Yeni Akit. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Australian Bureau of Statistics". Abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". Migration Policy Institute. 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Informatii utile | Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii (2002 census) (in Romanian)

- ^ "(number of foreigners in the Czech Republic)" (PDF) (in Czech). 31 December 2016. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Доля титульной национальности возрастает во всех странах СНГ, кроме России". Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "출입국·외국인정책 통계월보". 출입국·외국인정책 본부 이민정보과. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ "Total population by regions and ethnicity". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Utrikes födda efter födelseland, kön och år". www.scb.se. Statistiska Centralbyrån. Retrieved 25 May 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "(2000 census)". Stats.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "(2002 census)". Nsi.bg. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ "The Main Results of RA Census 2022, trilingual / Armenian Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia". www.armstat.am. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "rcnk.gr". April 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "ПОПИС 2022 - еxcел табеле | О ПОПИСУ СТАНОВНИШТВА". Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "Центральная избирательная комиссия Российской Федерации". www.foreign-countries.vybory.izbirkom.ru. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "SODB2021 – Obyvatelia – Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "SODB2021 – Obyvatelia – Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Statistics Denmark 2019 K4: Russian". Statistics Denmark. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Census ethnic group profiles: Russian". Stats NZ. 2013. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ a b Balanovsky, Oleg; Rootsi, Siiri; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Kivisild, Toomas; Churnosov, Michail; Evseeva, Irina; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Boldyreva, Margarita; Yankovsky, Nikolay; Balanovska, Elena; Villems, Richard (January 2008). "Two sources of the Russian patrilineal heritage in their Eurasian context". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–50. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- ^ a b Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 173–4, The Russians.

- ^ a b c Malyarchuk & Derenko 2004, pp. 877–900.

- ^ a b c d e f Balanovsky & Rootsi 2008, pp. 236–50.

- ^ a b Balanovsky 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Coolican, Sarah (December 2021). "The Russian Diaspora in the Baltic States: The Trojan Horse that never was" (PDF). LSE Ideas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Milner-Gulland 1997, pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b Kappeler, Andreas (2023). Ungleiche Brüder: Russen und Ukrainer vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart [Unequal Brothers: Russians and Ukrainians from the Middle Ages to the Present] (in German). München: C.H.Beck oHG. ISBN 978-3-406-80042-9.

- ^ Duczko, Wladyslaw (2004). Viking Rus. Brill Publishers. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-90-04-13874-2. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Kappeler, Andreas (2022). Russische Geschichte [Russian History] (in German). München: C.H.Beck oHG. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-406-79290-8.

- ^ For a discussion of the origins of Slavs, see Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs. Cornell University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-8014-3977-3.

- ^ a b Christian, D. (1998). A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 286–288. ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3.

- ^ a b Backus, Oswald P. (1973). "The impact of the Baltic and Finnic peoples upon Russian history". Journal of Baltic Studies. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/01629777300000011. ISSN 0162-9778.

- ^ Paszkiewicz, H.K. (1963). The Making of the Russian Nation. Darton, Longman & Todd. p. 262.

- ^ McKitterick, R. (15 June 1995). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. p. 497. ISBN 0521364477.

- ^ Mongaĭt, A.L. (1959). Archeology in the U.S.S.R. Foreign Languages Publishing House. p. 335.

- ^ Ed. Timothy Reuter, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 494-497. ISBN 0-521-36447-7.

- ^ Interactions between gene pools of Russian and Finnish-speaking populations from tver region: Analysis of 4 million snp markers. 2020. Bull Russ State Med Univ. 6, 15-22. O.P. Balanovsky, I.O. Gorin, Y.S. Zapisetskaya, A.A. Golubeva, E.V. Kostryukova, E.V. Balanovska. doi: 10.24075/BRSMU.2020.072.

- ^ The Primary Chronicle is a history of the Ancient Rus' from around 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113.

- ^ Roesdahl, Else (30 April 1998). The Vikings. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-194153-0. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ a b Borrero 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (2005). Russian Identities: A Historical Survey. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-515650-8. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023.

- ^ Hosking, Geoffrey; Service, Robert, eds. (1998). Russian Nationalism, Past and Present. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 9781349265329.

- ^ Channon, John; Hudson, Robert (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia. Viking. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-670-86461-4. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Moss, Walter G. (1 July 2003). A History of Russia Volume 1: To 1917. Anthem Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-84331-023-5. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Chew, Allen F. (1 January 1970). An Atlas of Russian History: Eleven Centuries of Changing Borders. Yale University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-300-01445-7. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Payne, Robert; Romanoff, Nikita (1 October 2002). Ivan the Terrible. Cooper Square Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4616-6108-5. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "EAll- Russian population census 2010 – Population by nationality, sex and subjects of the Russian Federation". Demoscope Weekly. 2010. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Curtis, Glenn E., ed. (1998). Russia: A Country Study. Area handbook series. Library of Congress, Federal Research Division (1st ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 429. ISBN 0-8444-0866-2. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021.

The problem of discrimination and ethnic violence against the 25 million ethnic Russians living in the new states was a growing concern in relations with several of the former Soviet republics.

- ^ Russians left behind in Central Asia Archived 15 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 23 November 2005.

- ^ Wallace, Donald Mackenzie (1914). A short history of Russia and the Balkan states. Internet Archive. London Encyclopaedia Britannica Co.

- ^ "Saving the souls of Russia's exiled Lipovans Archived 20 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The Daily Telegraph. 9 April 2013.

- ^ "The Ghosts of Russia That Haunt Shanghai Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine". The New York Times. 21 September 1999.

- ^ * Sidorov, Harun (7 January 2023). ""Русский мир" Путина и "кот Шредингера"" [Putin's "Russian World" and "Schrödinger's cat"]. idelreal.org (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 January 2023.

- "5 Million Fewer Than in 2010, Ethnic Russians Make Up Only 72 Percent of Russia's Population". Eurasia Daily Monitor. Vol. 20, no. 6. The Jamestown Foundation. 10 January 2023. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023.

- "Russia's population nightmare is going to get even worse". The Economist. 4 March 2023. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023.

The decline was largest among ethnic Russians, whose number, the census of 2021 said, fell by 5.4m in 2010-21. Their share of the population fell from 78% to 72%.

- ^ Alexandrov, Vlasova & Polishchuk 1997, pp. 107–123.

- ^ Zelenin 1991, §§ 1–4.

- ^ Shmeleva 1994, p. 283.

- ^ Teriukov, A.I. (2016). "Поморы" [Pomors]. Большая российская энциклопедия/Great Russian Encyclopedia Online (in Russian). Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ O'Rourke, Shane (2000). Warriors and peasants: The Don Cossacks in late imperial Russia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22774-6. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Balanovsky 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Balanovsky 2012, p. 13.

- ^ a b Balanovsky 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Sankina 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Usoltsev, Dmitrii; Kolosov, Nikita; Rotar, Oxana; Loboda, Alexander; Boyarinova, Maria; Moguchaya, Ekaterina; Kolesova, Ekaterina; Erina, Anastasia; Tolkunova, Kristina; Rezapova, Valeriia; Molotkov, Ivan; Melnik, Olesya; Freylikhman, Olga; Paskar, Nadezhda; Alieva, Asiiat (23 July 2024). "Complex trait susceptibilities and population diversity in a sample of 4,145 Russians". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 6212. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.6212U. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-50304-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11266540. PMID 39043636.

We present the analysis of genetic and phenotypic data from a cohort of 4,145 individuals collected in three metro areas in western Russia. We show the presence of multiple admixed genetic ancestry clusters spanning from primarily European to Asian and high identity-by-descent sharing with the Finnish population. As a result, there was notable enrichment of Finnish-specific variants in Russia. ... In addition, another study showed that Siberian populations separated from other East Asian populations 8800–11,200 years ago and significantly contributed to the formation of Eastern European populations 4700–8000 years ago16. ... Our cohort illustrates that the genetic structure of the Russian population, sampled in metropolitan areas in the European part of the country, consists of the number of subpopulations with high relatedness to Finnish and East Asian populations. We also identified a subgroup that has Central Asian origins.

- ^ Lamnidis, Thiseas C.; Majander, Kerttu; Jeong, Choongwon; Salmela, Elina; Wessman, Anna; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Khartanovich, Valery; Balanovsky, Oleg; Ongyerth, Matthias; Weihmann, Antje; Sajantila, Antti; Kelso, Janet; Pääbo, Svante; Onkamo, Päivi; Haak, Wolfgang (27 November 2018). "Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.5018L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6258758. PMID 30479341.

This model, however, does not fit well for present-day populations from north-eastern Europe such as Saami, Russians, Mordovians, Chuvash, Estonians, Hungarians, and Finns: they carry additional ancestry seen as increased allele sharing with modern East Asian populations1,3,9,10. [qpAdm results in supplementary data 4.]

- ^ Peltola, Sanni; Majander, Kerttu; Makarov, Nikolaj; Dobrovolskaya, Maria; Nordqvist, Kerkko; Salmela, Elina; Onkamo, Päivi (9 January 2023). "Genetic admixture and language shift in the medieval Volga-Oka interfluve". Current Biology. 33 (1): 174–182.e10. Bibcode:2023CBio...33E.174P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.036. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 36513080.

- ^ Balanovsky, Oleg; Rootsi, Siiri; Pshenichnov, Andrey; Kivisild, Toomas; Churnosov, Michail; Evseeva, Irina; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Boldyreva, Margarita; Yankovsky, Nikolay; Balanovska, Elena; Villems, Richard (10 January 2008). "Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–250. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- ^

Nițescu, Julia (15 December 2022). "From Individual Destinies to an Emergent Community: Latins in Sixteenth-Century Moscow". In Simon Dreher, Simon; Mueller, Wolfgang (eds.). Foreigners in Muscovy: Western Immigrants in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Russia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000802986. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

Conversion to Orthodoxy became a rather common means for accessing positions at the court or entering the service of the grand prince. As the Muscovite state grew, it became the preferred method for integrating non-Orthodox individuals, whether Latins or Tatars.

- ^

Khazanov, Anatoly M. (10 November 2020) [2003]. "A State without a Nation? Russia after empire". In T. V. Paul, T. V.; Ikenberry, G. John; Hall, John A. (eds.). The Nation-State in Question. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780691221496. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

Russian nationalists considered linguistic and even cultural assimilation insufficient. To them and even to the majority of the general public, the sine qua non of assimilation was conversion to Orthodoxy. The Russian literature is abundant with characters of non-Russian ancestry who refer to their profession of the Orthodox faith in order to prove their Russianness.

- ^ For example: Koldovskaya, Mariya (1998). "Хочешь быть русским - будь им!". Voĭna i rabochiĭ klass. Izd. gazety "Trud". p. 11. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Chapter 3. The Federal Structure". Constitution of Russia. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

1. The Russian language shall be a state language on the whole territory of the Russian Federation.

- ^ "The 10 Most Spoken Languages in Europe". Tandem. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Russian". University of Toronto. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

Russian is the most widespread of the Slavic languages and the largest native language in Europe. Of great political importance, it is one of the official languages of the United Nations – making it a natural area of study for those interested in geopolitics.

- ^ "Usage statistics of content languages for websites". W3Techs. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Wakata, Koichi. "My Long Mission in Space". JAXA. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

The official languages on the ISS are English and Russian, and when I was speaking with the Flight Control Room at JAXA's Tsukuba Space Center during ISS systems and payload operations, I was required to speak in either English or Russian.

- ^ "Official Languages". United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

There are six official languages of the UN. These are Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. The correct interpretation and translation of these six languages, in both spoken and written form, is very important to the work of the Organization, because this enables clear and concise communication on issues of global importance.

- ^ a b Kahn et al. 2018.

- ^ Zenkovsky, Serge A. (1963). Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles and Tales. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 222–228, Literature.

- ^ Prose, Francine; Moser, Benjamin (25 November 2014). "What Makes the Russian Literature of the 19th Century So Distinctive?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Emerson, Caryl (1998). "Pushkin, Literary Criticism, and Creativity in Closed Places". New Literary History. 29 (4). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 653–672. doi:10.1353/nlh.1998.0040. JSTOR 20057504. S2CID 144165201.

...and Pushkin, adapting to the transition with ingenuity and uneven success, became Russia's first fully profes-sional writer.

- ^ Strakhovsky, Leonid I. (October 1953). "The Historianism of Gogol". The American Slavic and East European Review (Slavic Review). 12 (3). Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies: 360–370. doi:10.2307/2491790. JSTOR 2491790.

- ^ Henry Chamberlin, William (1946). "Turgenev: The Eternal Romantic". The Russian Review. 5 (2). Wiley: 10–23. doi:10.2307/125154. JSTOR 125154.

- ^ Pritchett, V.S. (7 March 1974). "Saint of Inertia". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Neuhäuser, Rudolf (1980). "The Early Prose of Saltykov-Shchedrin and Dostoevskii: Parallels and Echoes". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 22 (3): 372–387. doi:10.1080/00085006.1980.11091635. JSTOR 40867755.

- ^ Muckle, James (1984). "Nikolay Leskov: educational journalist and imaginative writer". New Zealand Slavonic Journal. Australia and New Zealand Slavists' Association: 81–110. JSTOR 40921231.

- ^ Boyd, William (3 July 2004). "A Chekhov lexicon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

...Chekhov, whatever his standing as a playwright, is quite probably the best short-story writer ever.

- ^ Pirie, Gordon; Chandler, Robert (2009). "Eight Tales from Ivan Krylov". Translation and Literature. 18 (1). Edinburgh University Press: 64–85. doi:10.3366/E096813610800037X. JSTOR 40340118.

- ^ Gifford, Henry (1948). "Belinsky: One Aspect". The Slavonic and East European Review. 27 (68): 250–258. JSTOR 4204011.

- ^ Brintlinger, Angela (2003). "The Persian Frontier: Griboedov as Orientalist and Literary Hero". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 45 (3/4): 371–393. doi:10.1080/00085006.2003.11092333. JSTOR 40870888. S2CID 191370504.

- ^ Beasly, Ina (1928). "The Dramatic Art of Ostrovsky. (Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky, 1823–86)". The Slavonic and East European Review. 6 (18): 603–617. JSTOR 4202212.

- ^ Markov, Vladimir (1969). "Balmont: A Reappraisal". Slavic Review. 28 (2): 221–264. doi:10.2307/2493225. JSTOR 2493225. S2CID 163456732.

- ^ Tikhonov, Nikolay (November 1946). "Gorky and Soviet Literature". The Slavonic and East European Review. 25 (64). Modern Humanities Research Association: 28–38. JSTOR 4203794.

- ^ Lovell, Stephen (1998). "Bulgakov as Soviet Culture". The Slavonic and East European Review. 76 (1). Modern Humanities Research Association: 28–48. JSTOR 4212557.

- ^ Grosshans, Henry (1966). "Vladimir Nabokov and the Dream of Old Russia". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 7 (4). University of Texas Press: 401–409. JSTOR 40753878.

- ^ Rowley, David G. (July 1997). "Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Russian Nationalism". Journal of Contemporary History. 32 (3). SAGE Publishing: 321–337. doi:10.1177/002200949703200303. JSTOR 260964. S2CID 161761611.

- ^ Aslanyan, Anna (8 April 2011). "Revolutions and resurrections: How has Russia's literature changed?". The Independent. Retrieved 18 May 2024.

- ^ Lossky 1952.

- ^ Bevir, Mark (1994). "The West Turns Eastward: Madame Blavatsky and the Transformation of the Occult Tradition". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 62 (3). Oxford University Press: 747–767. doi:10.1093/jaarel/LXII.3.747. JSTOR 1465212.

- ^ Kelly, Aileen (1980). "The Destruction of Idols: Alexander Herzen and Francis Bacon". Journal of the History of Ideas. 41 (4). University of Pennsylvania Press: 635–662. doi:10.2307/2709278. JSTOR 2709278.

- ^ Rezneck, Samuel (1927). "The Political and Social Theory of Michael Bakunin". The American Political Science Review. 21 (2). American Political Science Association: 270–296. doi:10.2307/1945179. JSTOR 1945179. S2CID 147141998.

- ^ Adams, Matthew S. (2014). "Rejecting the American Model: Peter Kropotkin's Radical Communalism". History of Political Thought. 35 (1). Imprint Academic: 147–173. JSTOR 26227268.

- ^ Schuster, Charles I. (1985). "Mikhail Bakhtin as Rhetorical Theorist". College English. 47 (6). National Council of Teachers of English: 594–607. doi:10.2307/377158. JSTOR 377158. S2CID 141332657.

- ^ Brom, Libor (1988). "Dialectical Identity and Destiny: A General Introduction to Alexander Zinoviev's Theory of the Soviet Man". Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature. 42 (1/2). Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association: 15–27. doi:10.2307/1347433. JSTOR 1347433. S2CID 146768452.

- ^ Rutland, Peter (December 2016). "Geopolitics and the Roots of Putin's Foreign Policy". Russian History. 43 (3–4). Brill Publishers: 425–436. doi:10.1163/18763316-04304009. JSTOR 26549593.

- ^ Usitalo, Steven A. (2011). "Lomonosov: Patronage and Reputation at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 59 (2). Franz Steiner Verlag: 217–239. doi:10.25162/jgo-2011-0011. JSTOR 41302521. S2CID 252450664.

- ^ Vucinich, Alexander (1960). "Mathematics in Russian Culture". Journal of the History of Ideas. 21 (2). University of Pennsylvania Press: 161–179. doi:10.2307/2708192. JSTOR 2708192.

- ^ Leicester, Henry M. (1948). "Factors Which Led Mendeleev to the Periodic Law". Chymia. 1. University of California Press: 67–74. doi:10.2307/27757115. JSTOR 27757115.

- ^ Rappaport, Karen D. (October 1981). "S. Kovalevsky: A Mathematical Lesson". The American Mathematical Monthly. 88 (8). Taylor & Francis: 564–574. doi:10.2307/2320506. JSTOR 2320506.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (1 July 2010). "A Math Problem Solver Declines a $1 Million Prize". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (22 August 2006). "Highest Honor in Mathematics Is Refused". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Marsh, Allison (30 April 2020). "Who Invented Radio: Guglielmo Marconi or Aleksandr Popov?". IEEE Spectrum. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Shampo, Marc A.; Kyle, Robert A.; Steensma, David P. (January 2012). "Nikolay Basov—Nobel Prize for Lasers and Masers". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (1): e3. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.003. PMC 3498096. PMID 22212977.

- ^ Ivanov, Sergey (10 September 2019). "Remembering Zhores Alferov". Nature Photonics. 13 (10): 657–659. Bibcode:2019NaPho..13..657I. doi:10.1038/s41566-019-0525-0. S2CID 203099794.

- ^ Zheludev, Nikolay (April 2007). "The life and times of the LED — a 100-year history". Nature Photonics. 1 (4): 189–192. Bibcode:2007NaPho...1..189Z. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2007.34.

- ^ Ghilarov, Alexej M. (June 1995). "Vernadsky's Biosphere Concept: An Historical Perspective". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 70 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 193–203. doi:10.1086/418982. JSTOR 3036242. S2CID 85258634.

- ^ Gordon, Siamon (3 February 2016). "Elie Metchnikoff, the Man and the Myth". Journal of Innate Immunity. 8 (3): 223–227. doi:10.1159/000443331. PMC 6738810. PMID 26836137.

- ^ Anrep, G. V. (December 1936). "Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. 1849–1936". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 2 (5). Royal Society: 1–18. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1936.0001. JSTOR 769124.

- ^ Gorelik, Gennady (August 1997). "The Top-Secret Life of Lev Landau". Scientific American. 277 (2). Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc.: 72–77. Bibcode:1997SciAm.277b..72G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0897-72. JSTOR 24995874.

- ^ Janick, Jules (1 June 2015). "Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov: Plant Geographer, Geneticist, Martyr of Science" (PDF). HortScience. 50 (6): 772–776. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.50.6.772. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Hunsaker, Jerome C. (15 April 1954). "A Half Century of Aeronautical Development". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 98 (2). American Philosophical Society: 121–130. JSTOR 3143642.

- ^ "Vladimir Zworykin". Lemelson–MIT Prize. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Ford, Edmund Brisco (November 1977). "Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky, 25 January 1900 – 18 December 1975". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 23: 58–89. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1977.0004. ISSN 1748-8494. PMID 11615738.

- ^ "The Distinguished Life and Career of George Gamow". University of Colorado Boulder. 11 May 2016. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2000). Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974. United States Government Publishing Office. ISBN 978-0-160-61305-0.

- ^ "Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova becomes the first woman in space". History. A&E Networks. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

On June 16, 1963, aboard Vostok 6, Soviet Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova becomes the first woman to travel into space.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (13 October 2014). "The First Spacewalk". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 232–233, Architecture and Painting.

- ^ Curtis & Leighton 1998, Chapter 1–2. Historical Setting.

- ^ Grover, Stuart R. (January 1973). "The World of Art Movement in Russia". The Russian Review. 32 (1). Wiley: 28–42. doi:10.2307/128091. JSTOR 128091.

- ^ Dianina, Katia (2018). "The Making of an Artist as National Hero". Slavic Review. 77 (1). Cambridge University Press: 122–150. doi:10.1017/slr.2018.13. JSTOR 26565352. S2CID 165942177.

- ^ Sibbald, Balb (5 February 2002). "If the soul is nourished ..." Canadian Medical Association Journal. 166 (3): 357–358. PMC 99322.

- ^ Leek, Peter (2012). Russian Painting. Parkstone International. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-780-42975-5.

- ^ Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1975). "The Peredvizhniki and the Spirit of the 1860s". The Russian Review. 34 (3). Wiley: 247–265. doi:10.2307/127973. JSTOR 127973.

- ^ Brunson, Molly (2016). Russian Realisms. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-60909-199-6. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv177td37.

- ^ Reeder, Roberta (July 1976). "Mikhail Vrubel': A Russian Interpretation of "fin de siècle" Art". The Slavonic and East European Review. 54 (3). Modern Humanities Research Association: 323–334. JSTOR 4207296.

- ^ Archer, Kenneth (1986). "Nicholas Roerich and His Theatrical Designs: A Research Survey". Dance Research Journal. 18 (2). Dance Studies Association: 3–6. doi:10.2307/1478046. JSTOR 1478046. S2CID 191516851.

- ^ Birnholz, Alan C. (September 1973). "Notes on the Chronology of El Lissitzky's Proun Compositions". The Art Bulletin. 55 (3). CAA: 437–439. doi:10.2307/3049132. JSTOR 3049132.

- ^ Salmond, Wendy (2002). "The Russian Avant-Garde of the 1890s: The Abramtsevo Circle". The Journal of the Walters Art Museum. 60/61. The Walters Art Museum: 7–13. JSTOR 20168612.

- ^ a b c Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 228–230, Music.

- ^ Norris, Gregory (1980). Stanley, Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. p. 707. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- ^ Roth, Henry (1997). Violin Virtuosos: From Paganini to the 21st Century. California Classic Books. ISBN 1-879395-15-0.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (22 November 2000). "Perfect isn't good enough". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

Thirty years ago Gidon Kremer was rated as one of the world's outstanding violinists. Then he really started making waves...

- ^ Wilson, Elizabeth (2007). Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-22051-9.

- ^ Dubal, David (1993). Remembering Horowitz: 125 Pianists Recall a Legend. Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-870676-5.

- ^ Hunt, John (2009). Sviatoslav Richter: Pianist of the Century: Discography. London: Travis & Emery. ISBN 978-1-901395-99-0.

- ^ Carrick, Phil (21 September 2013). "Emil Gilels: A True Giant of the Keyboard". ABC Classic. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Spreng, Sebastian (19 December 2012). "Galina Vishnevskaya, the Russian tigress". Knight Foundation. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia – Music". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Smale, Alison (28 February 2000). "A Superstar Evokes a Superpower; In Diva's Voice, Adoring Fans Hear Echoes of Soviet Days". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Scaruffi, Piero. "Ganelin Trio". Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

The Ganelin Trio was the greatest ensemble of free-jazz in continental Europe, namely in Russia. Like other European improvisers, pianist Vyacheslav Ganelin, woodwind player Vladimir Chekasin and percussionist Vladimir Tarasov too found a common ground between free-jazz and Dadaism. Their shows were as much music as they were provocative antics.

- ^ McGrane, Sally (21 October 2014). "Boris Grebenshikov: 'The Bob Dylan of Russia'". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Pellegrinelli, Lara (6 February 2008). "DDT: Notes from Russia's Rock Underground". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

For the Russian band DDT, it was hard enough being a rock group under the Soviet regime. The band, which formed in 1981, gave secret concerts in apartments, bomb shelters, and even kindergarten classrooms to avoid the attention of authorities... Later, the policies of perestroika allowed bands to perform out in the open. DDT went on to become one of Russia's most popular acts...

- ^ O'Connor, Coilin (23 March 2021). "'Crazy Pirates': The Leningrad Rockers Who Rode A Wind Of Change Across The U.S.S.R." Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Musician, Songwriter, Cultural Force: Remembering Russia's Viktor Tsoi". Radio Liberty. 12 August 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

Also in 1982, Tsoi formed the band Kino and the group recorded its first album, 45... Tsoi and Kino quickly became a sensation... In 1986, the band released Khochu peremen – an anthem calling on the young generation to become more active and demand political change. The song made Kino's reputation across the Soviet Union...

- ^ "Tatu bad to be true". The Age. 14 June 2003. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Faramarzi, Sabrina (12 May 2019). "Little Big: camp, outrageous Russian rave". Medium. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Hodgson, Jonathan (4 December 2020). "EISENSTEIN, Sergei – BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN – 1925 Russia". Middlesex University. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Miller, Jamie. "Soviet Cinema, 1929–41: The Development of Industry and Infrastructure Archived 27 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine" Europe-Asia Studies, vol. 58, no. 1, 2006, pp. 103–124. JSTOR. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Brown, Mike (22 January 2018). "Sergei Eisenstein: How the "Father of Montage" Reinvented Cinema". Inverse. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Gray, Carmen (27 October 2015). "Where to begin with Andrei Tarkovsky". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "All-Union State Institute of Cinematography". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Teare, Kendall (12 August 2019). "Yale film scholar on Dziga Vertov, the enigma with a movie camera". Yale University. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ "Eldar Ryazanov And His Films". Radio Free Europe. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Eldar Ryazanov, a Russian film director whose iconic comedies captured the flavor of life and love in the Soviet Union while deftly skewering the absurdities of the communist system... His films ridiculed Soviet bureaucracy and trained a clear eye on the predicaments and peculiarities of daily life during the communist era, but the light touch of his satire helped him dodge government censorship.

- ^ Prokhorova, Elena, "The Man Who Made Them Laugh: Leonid Gaidai, the King of Soviet Comedy", in Beumers, Birgit (2008) A History of Russian Cinema, Berg Publishers, ISBN 978-1845202156, pp. 519–542

- ^ Birgit Beumers. A History of Russian Cinema. Berg Publishers (2009). ISBN 978-1-84520-215-6. p. 143.

- ^ "White Sun of the Desert". Film Society of Lincoln Center. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Dickerson, Jeff (31 March 2003). "'Russian Ark' a history in one shot". The Michigan Daily. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Aris, Ben (18 January 2019). "The Revival of Russia's Cinema Industry". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Rem Koolhaas, James Westcott, Stephan Petermann (2017). Elements of Architecture. Taschen. p. 102. ISBN 978-3-8365-5614-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rappoport, Pavel A. (1995). Building the Churches of Kievan Russia. Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 9780860783275.

- ^ Voyce, Arthur (1957). "National Elements in Russian Architecture". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 16 (2): 6–16. doi:10.2307/987741. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 987741.

- ^ Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya; Ching, Frank (2010). A Global History of Architecture 2nd Edition. John Wiley & Sons. p. 544. ISBN 978-0470402573.

- ^ Lidov, Alexei (2005). "The Canopy over the Holy Sepulchre. On the Origin of Onion-Shaped Domes". Academia.edu: 171–180. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022.

- ^ a b Shvidkovsky, Dmitry (2007). Russian Architecture and the West. Yale University Press. p. 480. ISBN 9780300109122.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (1995). Northern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 657. ISBN 9781884964015. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023.

- ^ Munro, George (2008). The Most Intentional City: St. Petersburg in the Reign of Catherine the Great. Cranbury, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780838641460.

- ^ Lodder, Christina (1985). Russian Constructivism. Yale University Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0300034066.

- ^ Tarkhanov, Alexei; Kavtaradze, Sergei (1992). Architecture of the Stalin Era. Rizzoli. p. 192. ISBN 9780847814732.

- ^ a b Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 203–210, The Russian Orthodox Church.

- ^ Shmeleva 1994, p. 270.

- ^ There is no official census of religion in Russia, and estimates are based on surveys only. In August 2012, ARENA Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine determined that about 46.8% of Russians are Christians (including Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and non-denominational), which is slightly less than an absolute 50%+ majority. However, later that year the Levada Center Archived 31 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine determined that 76% of Russians are Christians, and in June 2013 the Public Opinion Foundation Archived 15 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine determined that 65% of Russians are Christians. These findings are in line with Pew Archived 10 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine's 2010 survey, which determined that 73.3% of Russians are Christians, with VTSIOM Archived 29 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine's 2010 survey (~77% Christian), and with Ipsos MORI Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine's 2011 survey (69%).

- ^ Верю — не верю Archived 27 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Опубликована подробная сравнительная статистика религиозности в России и Польше (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Berdyaev, Nikolai (1999) [1916]. "Spiritual Christianity and Setvctarianism in Russia". Russkaya Mysl ("Russian Thought"). Translated by S. Janos. Archived from the original on 19 July 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023 – via Berdyaev.com.

- ^ "Арена". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "statistics". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Curtis & Leighton 1998, pp. 210–220, Other Religions.

- ^ Shnirelman, Victor (2002). "Christians! Go home": A Revival of Neo-Paganism between the Baltic Sea and Transcaucasia Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Contemporary Religion, Vol. 17, No. 2.

- ^ Murdico, Suzanne J. (2005). Russia: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. Rosen Publishing. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4042-2913-6. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ "EURO 1960: all you need to know". UEFA Champions League. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Classics: Soviet Union vs Netherlands, 1988". UEFA Champions League. 29 May 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Sporting-CSKA Moskva: watch their 2005 final". UEFA Champions League. 7 August 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Terry, Joe (18 November 2019). "How a brilliant Zenit Saint Petersburg lifted the UEFA Cup in 2008". These Football Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (26 June 2008). "Euro 2008: Russia v Spain – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "2018 FIFA Confederations Cup Russia 2017". FIFA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™". FIFA. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b Crandell, Lisa; Wilson, Josh (3 December 2009). "Russians on Ice: A Brief Overview of Soviet and Russian Hockey". GeoHistory. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ VanDerWerff, Emily (22 February 2019). "How Soviet hockey ruled the world — and then fell apart". Vox. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Trisvyatsky, Ilya (14 February 2013). "Bandy: A concise history of the extreme sport". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Gancedo, Javier (16 September 2007). "EuroBasket 2007 final: September 16, 2007". EuroLeague. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Russia – Sochi". Formula One. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Russian mastery in synchronized swimming yields double gold". USA Today. 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Jennings, Rebecca (18 February 2021). "Figure skating is on thin ice. Here's how to fix it". Vox. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Cioth, Peter (9 February 2021). "Roots of The Fall And Rise of Russian Tennis". Medium. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.