SIGABA

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

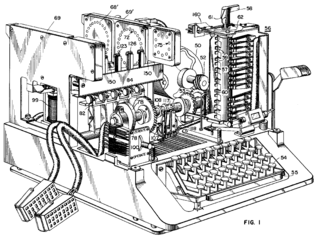

In the history of cryptography, the ECM Mark II was a cipher machine used by the United States for message encryption from World War II until the 1950s. The machine was also known as the SIGABA or Converter M-134 by the Army, or CSP-888/889 by the Navy, and a modified Navy version was termed the CSP-2900.

Like many machines of the era it used an electromechanical system of rotors to encipher messages, but with a number of security improvements over previous designs. No successful cryptanalysis of the machine during its service lifetime is publicly known.

History

[edit]

It was clear to US cryptographers well before World War II that the single-stepping mechanical motion of rotor machines (e.g. the Hebern machine) could be exploited by attackers. In the case of the famous Enigma machine, these attacks were supposed to be upset by moving the rotors to random locations at the start of each new message. This, however, proved not to be secure enough, and German Enigma messages were frequently broken by cryptanalysis during World War II.

William Friedman, director of the US Army's Signals Intelligence Service, devised a system to correct for this attack by truly randomizing the motion of the rotors. His modification consisted of a paper tape reader from a teletype machine attached to a small device with metal "feelers" positioned to pass electricity through the holes. When a letter was pressed on the keyboard the signal would be sent through the rotors as it was in the Enigma, producing an encrypted version. In addition, the current would also flow through the paper tape attachment, and any holes in the tape at its current location would cause the corresponding rotor to turn, and then advance the paper tape one position. In comparison, the Enigma rotated its rotors one position with each key press, a much less random movement. The resulting design went into limited production as the M-134 Converter, and its message settings included the position of the tape and the settings of a plugboard that indicated which line of holes on the tape controlled which rotors. However, there were problems using fragile paper tapes under field conditions.

Friedman's associate, Frank Rowlett, then came up with a different way to advance the rotors, using another set of rotors. In Rowlett's design, each rotor must be constructed such that between one and four output signals were generated, advancing one or more of the rotors (rotors normally have one output for every input). There was little money for encryption development in the US before the war, so Friedman and Rowlett built a series of "add on" devices called the SIGGOO (or M-229) that were used with the existing M-134s in place of the paper tape reader. These were external boxes containing a three rotor setup in which five of the inputs were live, as if someone had pressed five keys at the same time on an Enigma, and the outputs were "gathered up" into five groups as well — that is all the letters from A to E would be wired together for instance. That way the five signals on the input side would be randomized through the rotors, and come out the far side with power in one of five lines. Now the movement of the rotors could be controlled with a day code, and the paper tape was eliminated. They referred to the combination of machines as the M-134-C.

In 1935 they showed their work to Joseph Wenger, a cryptographer in the OP-20-G section of the U.S. Navy. He found little interest for it in the Navy until early 1937, when he showed it to Commander Laurance Safford, Friedman's counterpart in the Office of Naval Intelligence. He immediately saw the potential of the machine, and he and Commander Seiler then added a number of features to make the machine easier to build, resulting in the Electric Code Machine Mark II (or ECM Mark II), which the navy then produced as the CSP-889 (or 888).

Oddly, the Army was unaware of either the changes or the mass production of the system, but were "let in" on the secret in early 1940. In 1941 the Army and Navy joined in a joint cryptographic system, based on the machine. The Army then started using it as the SIGABA. Just over 10,000 machines were built.[1]: p. 152

On 26 June 1942, the Army and Navy agreed not to allow SIGABA machines to be placed in foreign territory except where armed American personnel were able to protect the machine.[2] The SIGABA would be made available to another Allied country only if personnel of that country were denied direct access to the machine or its operation by an American liaison officer who would operate it.[2]

Description

[edit]

SIGABA was similar to the Enigma in basic theory, in that it used a series of rotors to encipher every character of the plaintext into a different character of ciphertext. Unlike Enigma's three rotors however, the SIGABA included fifteen, and did not use a reflecting rotor.

The SIGABA had three banks of five rotors each; the action of two of the banks controlled the stepping of the third.

- The main bank of five rotors was termed the cipher rotors (Army) or alphabet maze (Navy) and each rotor had 26 contacts. This assembly acted similarly to other rotor machines, such as the Enigma; when a plaintext letter was entered, a signal would enter one side of the bank and exit the other, denoting the ciphertext letter. Unlike the Enigma, there was no reflector.

- The second bank of five rotors was termed the control rotors or stepping maze. These were also 26-contact rotors. The control rotors received four signals at each step. After passing through the control rotors, the outputs were divided into ten groups of various sizes, ranging from 1–6 wires. Each group corresponded to an input wire for the next bank of rotors.

- The third bank of rotors was called the index rotors. These rotors were smaller, with only ten contacts, and did not step during the encryption. After travelling though the index rotors, one to four of five output lines would have power. These then turned the cypher rotors.

The SIGABA advanced one or more of its main rotors in a complex, pseudorandom fashion. This meant that attacks which could break other rotor machines with simpler stepping (for example, Enigma) were made much more complex. Even with the plaintext in hand, there were so many potential inputs to the encryption that it was difficult to work out the settings.

On the downside, the SIGABA was also large, heavy, expensive, difficult to operate, mechanically complex, and fragile. It was nowhere near as practical a device as the Enigma, which was smaller and lighter than the radios with which it was used. It found widespread use in the radio rooms of US Navy ships, but as a result of these practical problems the SIGABA simply couldn't be used in the field. In most theatres other systems were used instead, especially for tactical communications. One of the most famous was the use of Navajo code talkers for tactical field communications in the Pacific Theater. In other theatres, less secure, but smaller, lighter, and sturdier machines were used, such as the M-209. SIGABA, impressive as it was, was overkill for tactical communications. This said, new speculative evidence emerged more recently that the M-209 code was broken by German cryptanalysts during World War II.[3]

Operation

[edit]

Because SIGABA did not have a reflector, a 26+ pole switch was needed to change the signal paths through the alphabet maze between the encryption and decryption modes. The long “controller” switch was mounted vertically, with its knob on the top of the housing. See image. It had five positions, O, P, R, E and D. Besides encrypt (E) and decrypt (D), it had a plain text position (P) that printed whatever was typed on the output tape, and a reset position (R) that was used to set the rotors and to zeroize the machine. The O position turned the machine off. The P setting was used to print the indicators and date/time groups on the output tape. It was the only mode that printed numbers. No printing took place in the R setting, but digit keys were active to increment rotors.

During encryption, the Z key was connected to the X key and the space bar produced a Z input to the alphabet maze. A Z was printed as a space on decryption. The reader was expected to understand that a word like “xebra” in a decrypted message was actually “zebra.” The printer automatically added a space between each group of five characters during encryption.

The SIGABA was zeroized when all the index rotors read zero in their low order digit and all the alphabet and code rotors were set to the letter O. Each rotor had a cam that caused the rotor to stop in the proper position during the zeroize process.

SIGABA's rotors were all housed in a removable frame held in place by four thumb screws. This allowed the most sensitive elements of the machine to be stored in more secure safes and to be quickly thrown overboard or otherwise destroyed if capture was threatened. It also allowed a machine to quickly switch between networks that used different rotor orders. Messages had two 5- character indicators, an exterior indicator that specified the system being used and the security classification and an interior indicator that determined the initial settings of the code and alphabet rotors. The key list included separate index rotor settings for each security classification. This prevented lower classification messages from being used as cribs to attack higher classification messages.

The Navy and Army had different procedures for the interior indicator. Both started by zeroizing the machine and having the operator select a random 5-character string for each new message. This was then encrypted to produce the interior indicator. Army key lists included an initial setting for the rotors that was used to encrypt the random string. The Navy operators used the keyboard to increment the code rotors until they matched the random character string. The alphabet rotor would move during this process and their final position was the internal indicator. In case of joint operations, the Army procedures were followed.

The key lists included a “26-30” check string. After the rotors were reordered according to the current key, the operator would zeroize the machine, encrypt 25 characters and then encrypt “AAAAA”. The ciphertext resulting from the five A's had to match the check string. The manual warned that typographical errors were possible in key lists and that a four character match should be accepted.

The manual also gave suggestions on how to generate random strings for creating indicators. These included using playing cards and poker chips, to selecting characters from cipher texts and using the SIGABA itself as a random character generator. [4]

Security

[edit]

Although the SIGABA was extremely secure, the US continued to upgrade its capability throughout the war, for fear of the Axis cryptanalytic ability to break SIGABA's code. When the German's ENIGMA messages and Japan's Type B Cipher Machine were broken, the messages were closely scrutinized for signs that Axis forces were able to read the US cryptography codes. Axis prisoners of war (POWs) were also interrogated with the goal of finding evidence that US cryptography had been broken. However, neither the Germans nor the Japanese were making any progress in breaking the SIGABA code. A decrypted JN-A-20 message, dated 24 January 1942, sent from the naval attaché in Berlin to vice chief of Japanese Naval General Staff in Tokyo stated that "joint Jap[anese]-German cryptanalytical efforts" to be "highly satisfactory", since the "German[s] have exhibited commendable ingenuity and recently experienced some success on English Navy systems", but are "encountering difficulty in establishing successful techniques of attack on 'enemy' code setup". In another decrypted JN-A-20 message, the Germans admitted that their progress in breaking US communications was unsatisfactory. The Japanese also admitted in their own communications that they had made no real progress against the American cipher system. In September 1944, when the Allies were advancing steadily on the Western front, the war diary of the German Signal Intelligence Group recorded: "U.S. 5-letter traffic: Work discontinued as unprofitable at this time".[5]

SIGABA systems were closely guarded at all times, with separate safes for the system base and the code-wheel assembly, but there was one incident where a unit was lost for a time. On February 3, 1945, a truck carrying a SIGABA system in three safes was stolen while its guards were visiting a brothel in recently liberated Colmar, France. General Eisenhower ordered an extensive search, which finally discovered the safes six weeks later in a nearby river.[6]: pp.510–512

Interoperability with Allied counterparts

[edit]The need for cooperation among US, British, and Canadian forces in carrying out joint military operations against Axis forces gave rise to the need for a cipher system that could be used by all Allied forces. This functionality was achieved in three different ways. Firstly, the ECM Adapter (CSP 1000), which could be retrofitted on Allied cipher machines, was produced at the Washington Naval Yard ECM Repair Shop. A total of 3,500 adapters were produced.[5] The second method was to adapt the SIGABA for interoperation with a modified British machine, the Typex. The common machine was known as the Combined Cipher Machine (CCM), and was used from November 1943.[2] Because of the high cost of production, only 631 CCMs were made. The third way was the most common and most cost-effective. It was the "X" Adapter manufactured by the Teletype Corporation in Chicago. A total of 4,500 of these adapters were installed at depot-level maintenance facilities.[5]

See also

[edit]- Mercury — British machine which also used rotors to control other rotors

- SIGCUM — teleprinter encryption system which used SIGABA-style rotors

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Jason Fagone (26 September 2017). The Woman Who Smashed Codes: A True Story of Love, Spies, and the Unlikely Heroine Who Outwitted America's Enemies. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-243050-2.

- ^ a b c Sterling, Christopher H (2008). Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. USA: ABC-CLIO. p. 565. ISBN 9781851097326.

- ^ Schmeh, Klaus (September 23, 2004). "Als deutscher Code-Knacker im Zweiten Weltkrieg" [As a German code-breaker in World War II]. Heise Online (in German). Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ CSP-1100 (C) Operating Instructions for ECM Mark 2 and CCM Mark 1, U.S.Department of the Navy, 1944

- ^ a b c d Timothy, Mucklow (2015). The SIGABA / ECM II Cipher Machine : "A Beautiful Idea" (PDF). Fort George G. Meade: Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing. New York: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5. OCLC 59019141

- Sources

- Mark Stamp, Wing On Chan, "SIGABA: Cryptanalysis of the Full Keyspace", Cryptologia v 31, July 2007, pp 201–2222

- Rowlett wrote a book about SIGABA (Aegean Press, Laguna Hills, California).

- Michael Lee, "Cryptanalysis of the Sigaba", Masters Thesis, University of California, Santa Barbara, June 2003 (PDF) (PS).

- John J. G. Savard and Richard S. Pekelney, "The ECM Mark II: Design, History and Cryptology", Cryptologia, Vol 23(3), July 1999, pp211–228.

- Crypto-Operating Instructions for ASAM 1, 1949, [1].

- CSP 1100(C), Operating Instructions for ECM Mark 2 (CSP 888/889) and CCM Mark 1 (CSP 1600), May 1944, [2].

- George Lasry, "A Practical Meet-in-the-Middle Attack on SIGABA", 2nd International Conference on Historical Cryptology, HistoCrypt 2019 [3].

- George Lasry, "Cracking SIGABA in less than 24 hours on a consumer PC", Cryptologia, 2021 [4].

External links

[edit]- Electronic Cipher Machine (ECM) Mark II by Rich Pekelney

- SIGABA simulator for Windows 32 bits OS

- CODEBOOK GENERATOR to create key lists for the Sigaba Simulator (Windows 98->Win 11)

- The ECM Mark II, also known as SIGABA, M-134-C, and CSP-889 — by John Savard

- Cryptanalysis of SIGABA, Michael Lee, University of California Santa Barbara Masters Thesis, 2003

- The SIGABA ECM Cipher Machine - A Beautiful Idea

- A Practical Meet-in-the-Middle Attack on SIGABA by George Lasry

KSF

KSF