Sacramento Valley Development Association

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

The Sacramento Valley Development Association was a quasi-public entity of colony land developers founded in 1900 to advance the area's political and commercial interests as well as market its agricultural products.[1] The organization, headquartered in Sacramento, was founded by 6 counties (Sacramento, Colusa, Yuba, Yolo, Sutter and Glenn)[2] but came to comprise representatives from 6 more (Solano, Butte, Shasta, Placer, El Dorado and Tehama), each selected by their respective county supervisor.[3] It remained operational and influential until 1925 when the Sacramento Valley Regional Advisory for the larger California Development Association filled the void.[4]

History

[edit]

Upon suggestion from local Woodland attorney C.W. Thomas, former Colusa mayor Will S. Green called on the Colusa County Board of Trade to request a meeting of delegates to the inaugural Sacramento Valley Irrigation Convention. On January 15 and 16, 1900, delegates from six counties gathered in Woodland where they formally elected General Green, a renowned state politician and fierce advocate for Central Valley irrigation, as President, a capacity in which he served until his death in 1905. Another meeting would be held soon afterward in Oroville to formalize the proceedings and make permanent the renamed Sacramento Valley Development Association, then headquartered in Colusa. The office was moved once more to Sacramento in 1903, where a building had been erected near the Southern Pacific train depot specifically for the group's purpose.[5]

Leadership

[edit]

After General Green's death in 1905, Yolo County Democratic state senator (1903–1907)[6][7] Marshall Diggs was elected President (with widespread support),[8] an office which he held for over 16 years. His director turned co-vice president for a time was C.H. Dunton.[5]

Dunton was an invaluable aide, if not partner, to Diggs. Although the two men hailed from different parts of Northern California (Dunton was from El Dorado) and different political parties, the two were a formidable duo. Different as the two were, both were widely respected across the state. As proof, Diggs had been considered for the governorship in 1906, Dunton the lieutenant governorship in 1914.[9][10] However, unlike Dunton, who had served as delegate to the state convention[11] and on a committee to the National Irrigation Congress,[12] Diggs wasn't particularly keen on politics. Diggs was "a business man, pure and simple", who "continually expressed a desire to get back to his ranch and to his business."[13]

Together they arranged meetings and luncheons with some of California's most influential so that, for example, members of the Commonwealth Club of California were there to hear Dunton's talk on "The Relationship of San Francisco to the Development of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys."[14]

During his tenure, Biggs was chosen by Dunton to serve on the Northern California Development League's 15-man conference committee, which he chaired, in order to unite the disparate organizations working to promote Northern California.[15] The irony in Dunton and Biggs' close involvement is that the decision to create such a League in the first place had been opposed principally by some members of their own organization, the Sacramento Valley Development Association. They agreed with Colonel John P. Irish, a member of the California Development Board, that the newly found organization of 33 counties was itself unnecessary. Irish contended at the organizing conference in Marysville that it would really only duplicate work of existing organizations which had already helped Northern California prosper as much as the southern part of the state.[16] Nevertheless, the conference, which focused on the method of advertising by which the most northern counties could be better brought into the fold and how Northern California could compete with Southern California for tourists, immigrants and consumers, was a success and convinced most of the prospective League members it was a good idea.[15][16]

After his reelection as President for the 16th straight year in 1921, Diggs stepped down in January 1922, at which time Vice President W.A. Beard took over.[17] With the exception of time spent on his run as the Democratic nominee for California's 2nd congressional district,[18] Beard had served continuously within the organization (manager, secretary, editor and vice president) since 1905.

Fundraising

[edit]With their organizational structure set after the Oroville meeting, the most daunting challenge the Association faced was the raising of funds. The financial situation was so dire that Green himself travelled the valley appealing to county supervisors for $50 apiece. Working within these economic limitations, the group threw its moral weight behind an education campaign regarding the unique opportunities and advantages of the region. They took actions to negotiate the subdivision of a large ranch in Glenn County, secure reports on irrigation possibilities from the Department of Agriculture and induce the Geological Survey to send experts to map sites for storage reservoirs (the first study of water storage problems in the valley).[5]

Such barebones campaigning wasn't sustainable, however, so a permanent rule was implemented that required each participating county to contribute one-half cent for every one hundred dollars of assessed valuation.[5] In April 1910, they partnered with the Sacramento Realty Board, who pledged $10,000 to the Association's proposed five year, $50,000 per year campaign for the development of the valley.[19] The first three years went towards an advertising campaign until the association established a magazine which they published for six years after that.[5]

Initiated and supported projects

[edit]As early as 1905, the Association had been pushing Congress for a comprehensive Sacramento Valley Project with a price tag of $40 million. With only $28 million in the Reclamation Fund at the time, the pitch was never plausible[20] but, in his last public activity, Green managed to bring members of the Irrigation Committees of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, accompanied by officials of the Department of the Interior and of the Reclamation Service, out for a two-day tour of the Sacramento Valley's current irrigation situation. At their most important stop in Red Bluff, a banquet was held, during which California Gov. George C. Pardee, Nevada Sen. Francis G. Newlands, Idaho Sen. Fred Dubois, California Reps. Duncan E. McKinlay and Theodore Arlington Bell, Wyoming Rep. Franklin Wheeler Mondell and California Sen. Frank Putnam Flint all spoke. However, it was Green who, weeks from death, stole the show. Detailing the aims and intentions of the Association, he recognized how little work had actually yet been accomplished before finishing with a singular wish: "But, gentlemen, my only hope, as I am on the decline of life, is that some day I may stand on Pisgah[21] and see a Promised Land for God's people in this valley. Then I will be ready to die."[22][23]

-

Woodland Geological Survey (February 1907)

-

East Park Dam near Orland (1915)

-

Creamery and Horticulture buildings, University Farm at Davis (between 1910 and 1923)

-

Surfacing the Yolo Causeway (between 1914 and 1916)

-

Lassen Volcanic National Park poster (1938)

Green never saw the completion of it, but one of his organization's early successes was the approval of the Orland Project on December 18, 1906, the result of letters from various officers throughout the years 1902 to 1905 as well as a petition from owners of over 40,000 acres of land conveyed through the Sacramento Valley Development Association to the Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock. Less than four years later, the East Park Dam had been constructed on Stony Creek, the Sacramento River's principal tributary from the west, along with a spillway, dikes and a system of canals capable of irrigating 53,000 acres 210 days out of the year.[24]

In September 1908, the Association called for a meeting of delegates across the state to discuss plans for improving the highways of California. An earlier suggested plan, which had yet to be enacted was proposed at the meeting by the Governor's secretary in his stead. It called for an $18 million bond to construct 3000 miles of roads including highways across the tules between Davis and Sacramento as well as a state highway connection from Folsom to Placerville.[25] The passage of the State Highways Act in 1909 and subsequent success of Proposition 2, The California State Highway Bonds Proposition, just over two years after the original meeting, provided $18 million in funds. This started the construction of 3,000 miles of roads including the Yolo Causeway in 1914 and the portion of U.S. Route 50 (then State Route 11) connecting Folsom and Placerville sometime before that. The road up the Feather River Canyon (now the northern part of California State Route 49) was also touted as a critical trans-Sierra highway.[26]

In 1905, at the urging of fellow Yolo County leaders, Marshall Diggs (still state senator) sponsored the State Farm Bill of 1905 which selected Davisville as the site for the University of California's new State Farmers' Institute, an adjunct to the university's College of Agriculture.[27] He and his fellow Yolo County leaders infamously had a hand in pushing Judge Peter J. Shields to pin a blue slip to the bill, which added an irrigation requirement disqualifying more than a dozen other locations (many in Southern California) but not Davisville. Three years later, on behalf of the Sacramento Valley Development Association, Diggs spoke with his predecessor in the state senate A.E. Boynton, U.S. Representatives Benjamin Franklin Rush and Horace Davis as well as UC Berkeley President Benjamin Ide Wheeler on the campus pavilion for the formal opening of short instructional classes open to all adults of at least 17 years of age.

The Association strongly supported the passage of John E. Raker's H.R. 348 bill, which created Lassen Volcanic National Park, even though it was criticized by some conservationists as a way to siphon federal funds to subsidize roads.[28]

The last large undertaking championed by the Association and President W.A. Beard's crowning achievement was the Iron Canyon Project on the upper Sacramento River, which would help to supply water for irrigation across 225,000 acres of land from Red Bluff to Glenn County west of the river. Beard and his director, A.L. Conrad, testified at a consequential record of public hearing in 1916 against opposition that wished to keep the river navigable up to Red Bluff year round. Beard, hyperbolic as always, cited "how [they were] sufficiently near to justify the War Department in providing us with this information", by which he meant the amount of water needed for storage and navigation. He emphasized the fact that development would reach its maximum output soon if storage capacity weren't increased, while others pointed to the decreasing navigability of the riverbed and banks.[29] In the end, inertia and a Shasta County Board of Supervisors campaign against the plan was enough to stall it for years to come. The Association soon dissolved itself and many of its members became founders of the Sacramento Valley Regional Advisory Council to the larger California Development Association, while Beard worked for several more years as the President of the Iron Canyon Project Association in an effort to secure federal aid.[30]

Publications and publicity

[edit]

The Development Association also published regular literature to promote their endeavors and attract consumers from within and to the area. Their very first venture was a 40-page illustrated article outlining the climate, soil, resources and advantages of all nine member counties. It was decided in December 1900 that their first buy would be in Sunset, a South Pacific-owned magazine aimed at promoting the West. Including the 15,000 copies printed by the State Board of Trade, 25,000 reached circulation in early 1901.[31] Later in the year, they published an article in 30,000 copies of the Overland Monthly, along with 10,000 in pamphlet form.[32] Most of these early pamphlets were written by President Green himself under straightforward titles such as "Northern California and the Sacramento Valley" or "The Sacramento Valley as a field for profitable investment", while others embellished "The Best Spot on Earth is the Sacramento Valley". One pamphlet from 1911 boasted of "one of the great valleys of the world, with a vast and fertile soil area. It produces great quantities of precious metals and structural materials. It is blessed with an abundant water supply, and an agriculture much more diversified than is found anywhere else on the face of the earth."[33]

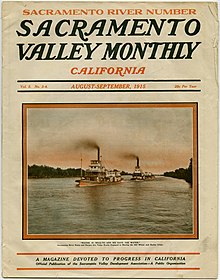

Monthly journals

[edit]In 1902, the association published a booster periodical called the Wednesday Press, which was renamed The Great West in October 1907 by manager turned editor W.A. Beard. As a booster, he tracked Sacramento's progress from what he called "one of the most backward and unprogressive cities on the entire Pacific Coast" to one in which "the population ... business ... property values have increased and every prominent interest in the city has been infused with life."[34] He signaled the dawn of a new era with headlines that alluded to science, "Substantial Evidence of Sacramento's New Growth", and faith, "Sacramento's New Awakening".[35] At this, he'd been a natural since his days as secretary-manager:

Redding is enjoying an era of growth such as comes to few cities of its size. I was told that the population is now less than 4,000, but the new buildings indicate a city of many thousand inhabitants. A $20,000 hotel is considered a prize by most towns of that size, but Redding has one that cost $75,000.[36]

— 1904 interview with the Sacramento Bee

In truth, Redding did not grow to over 4,000 inhabitants until 1930, but the narrative helped Beard, on behalf of the Association, make the demand for "the gridironing of the valley with railroads" among other things.[34]

Prominent Catholic journalist and booster Thomas Augustus Connelly also worked for a time as an associate editor under Beard and played a role in the name change. While most of his work was spent promoting the economic interests and growth of the area, he also covered its social development in pieces like "Sacramento's Numerous and Beautiful Church Structures", in which he highlighted each of the city's established denominations.[2]

Like the Great West, the Sacramento Valley Monthly focused on educational writing for a wide variety of agricultural topics such as sanitation, reclamation, irrigation, navigation, tributaries, dams, reservoirs, power, maps, hunting and fishing, but they also dabbled in tourism, education and immigration. Ads and coupons for railroad companies, land, banks/loans, cattle and crops were also largely the same. The biggest difference was the fact that the Great West was more than 30 pages longer. The extra space was used to feature projects, cities and counties and to expand its advertisements to physicians, grocers, hotels and even funeral directors. Both publications also often highlighted success stories of farmers and laborers who had come to the Sacramento Valley from the midwest and east for a better life.[37] One told of a man who moved from Moore, Oklahoma to Glenn County, another of an Illinois man who settled in Elk Grove, the latter of whom spoke of satisfaction owing to a quick 11% return on his investment and a friendly climate.[38][39]

Great Prune Bear

[edit]

One of the association's special promotional projects which gained brief national attention made its debut at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis.[1] The "Great Prune Bear", as they called it, was a life-sized bear made entirely of prunes adorned with gleaming teeth and flashing electric eyes, which attracted visitors and photographers from all over.[1] Each was given a folder on the advantages of the area and asked to estimate the number of fruits used in the bear's creation. As California became an agricultural powerhouse, the valley was transitioning to fruits and vegetables, hence why the much maligned prune was marketed so heavily.[1]

The next year, the same groups were granted $100,000 by the state legislature to represent the Sacramento Valley and California at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. Having received their own building this time around, many California exhibits embellished upon the last year's display. Yet, according to a final report by the state itself, none featured more items than Sacramento County, which included a 12-foot high mural of the Great Seal of California made entirely of beans, a model of the California State Capitol constructed of nuts and a pyramid of beer bottles from the Buffalo Brewery in the shape of a giant beer bottle. But, of course, none received as much publicity as the upgraded Great Prune Bear, located on the central rotunda and now featuring a graphophone in its jaws.[1]

Other notable members

[edit]- George Washington Pierce, Jr., Republican State Assemblyman (1898–1899)[5]

- Benjamin Franklin Rush, Republican State Senator (1905–1921, 1923–1927)[5][note 1]

- Louis Tarke, Rancher and 1914 Democratic Candidate for California's 6th Assembly District[5]

- ^ Rush switched his political party affiliation to Democratic during his second tenure

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "From Sacramento to Donner Summit" (PDF). Sacramento, CA: Sacramento County Historical Society. February 26, 2013. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Avella, Steven M. (Summer 2007). "The Catholic Press as Urban Booster: The Case of Thomas A. Connelly of Sacramento". U.S. Catholic Historian. 25 (3). Catholic University of America Press: 79. doi:10.1353/cht.2007.0019. JSTOR 25156636. S2CID 162238715.

- ^ "Sacramento Valley Monthly". Sacramento, CA: Sacramento Digital Room. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "Livermore Journal 13 March 1925 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h G. Walter Reed (1923). History of Sacramento County, California. Los Angeles: Historic Record Company. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-5-88230-133-9.

- ^ Person Record – Marshall Diggs, Sacramento, CA: Center for Sacramento History, retrieved March 11, 2017

- ^ "Record of State Senators 1849–2013" (PDF). Sacramento, CA: Secretary of the California State Senate. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "The Appointment of Senator Marshall". Woodland Daily Democrat. Woodland, CA. October 28, 1905. p. 3. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Marshall Diggs to be Candidate". Red Bluff Daily News. September 4, 1906. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "News Brevities From Northern and Central California Towns". Sacramento Union. Sacramento, CA. July 31, 1909. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Republicans of the State Who Will Meet in the Convention Today at Sacramento" (PDF). San Francisco Call. San Francisco, CA. May 18, 1904. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Waterways Committee to Hold Meeting". Sacramento Union. Sacramento, CA. November 9, 1907. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Praise is Given Marshall Diggs". Los Angeles Herald. Los Angeles, CA. September 1, 1906. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Transactions of the Commonwealth Club of California. San Francisco: Commonwealth of California. 1914. p. 639.

- ^ a b "Chairman C. H. Dunton Announces Members of Conference Committee". Sacramento, CA: Sacramento Union. November 23, 1913. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "League Formed to Boost Rich Sections". San Francisco Call. San Francisco, CA. November 21, 1913. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Beard Succeeds Diggs". Woodland Daily Democrat. Woodland, CA. January 23, 1922. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Beard Accepts". Woodland, CA: Woodland Daily Democrat. September 19, 1906. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Sacramento, Cal". The National Real Estate Journal. 1: 68, 70. April 15, 1910. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Pisani, Donald J. (August 1984). From the Family Farm to Agribusiness: The Irrigation Crusade in California, 1850–1931. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 325. ISBN 0520051270.

- ^ An allusion to the biblical Mount Pisgah, from where Moses was shown the Promised Land which he would not enter.

- ^ Beard, W. A. (October 1, 1905). "Red Bluff Banquet". Sacramento Valley Development Association Bulletins. Sacramento, CA: Sacramento Valley Development Association. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ McCormish, Charles David; Lambert, Rebecca T. (1918). History of Colusa and Glenn counties, California. Los Angeles, CA: Historic Record Company. p. 270.

- ^ Newell, F.H. (1911). Ninth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service, 1909–1910. Washington DC: Government Printing Office Service. pp. 84–88.

- ^ "Good Roads Delegates in Convention" (PDF). Los Angeles Herald. Los Angeles, CA. September 20, 1908. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Oakland Tribune from Oakland, California · Page 6". Oakland Tribune. Oakland, CA. October 3, 1924. p. 6. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ "The Week". Pacific Rural Press. San Francisco: Dewey Publishing Company. November 9, 1907.

- ^ United States Congressional serial set, Issue 6905. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1916. p. 20.

- ^ United States Congressional serial set, Issue 7148. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1917. pp. 64–66.

- ^ "Oakland Tribune from Oakland, California on August 13, 1928 · Page 3". Newspapers.com. August 13, 1928.

- ^ "Executive Committee, Sacramento Valley Development Association Holds Meeting". Red Bluff Daily News. Red Bluff, CA. December 19, 1900. Retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ Deibert, Ken (October 30, 2012). "As we were: Soroptimists recognize donors, Bartletts practice, Chrysler dealer and growth". Mountain Democrat. Placerville, California. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Sacramento Valley Transportation". Sacramento, CA: Historic Sacramento Photograph and Document Archive. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Avella, Steven M. (August 22, 2008). Sacramento and the Catholic Church: Shaping a Capital City. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0874177602.

- ^ Avella, Steven M. (August 22, 2008). Sacramento and the Catholic Church: Shaping a Capital City. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0874177602.

- ^ "Many Bodies Concerned". San Francisco Call. San Francisco, CA. January 18, 1904. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "City of Citrus Heights Historical Resources Survey". November 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Miller, E.S. (1909). "An Illinois Farmer in the Sacramento Valley". The Great West: A Journal of Development and Progress. Sacramento, CA: Sacramento Valley Development Association. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- ^ "Oklahoma Man's Success in Sacramento Valley". Sacramento Valley Monthly. Sacramento, CA: Sacramento Valley Development Association. 1912. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Notes on Will S. Green, the father of Glenn Colusa Irrigation District, 1949.

- Report on Iron Canyon Project, California, 1921.

KSF

KSF