Sahaja Yoga

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

| Sahaja Yoga | |

|---|---|

| Founder | Nirmala Srivastava (aka Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi) |

| Established | 5 May 1970 |

| Practice emphases | |

| kundalini, meditation, self-realization[1] | |

Sahaja Yoga (सहज योग) is a new religious movement founded in 1970 by Nirmala Srivastava (1923–2011).[2] Nirmala Srivastava is known as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi (trans: Revered Immaculate Mother) or simply as "Mother" by her followers, who are called Sahaja yogis.[3][4]

Practitioners believe that during meditation they experience a state of self-realization produced by kundalini awakening, and that this is accompanied by the experience of thoughtless awareness or mental silence.[5]

Shri Mataji described Sahaja Yoga as the pure, universal religion integrating all other religions.[3] She claimed that she was a divine incarnation,[6] more precisely an incarnation of the Holy Spirit, or the Adi Shakti of the Hindu tradition, the great mother goddess who had come to save humanity.[3][7] This is also how she is regarded by most of her devotees.[8] Sahaja Yoga has sometimes been characterized as a cult.[9][10]

Etymology

[edit]The word 'Sahaja' in Sanskrit has two components: 'Saha' is 'with' and 'ja' is 'born'.[6] A Dictionary of Buddhism gives the literal translation of Sahaja as "innate" and defines it as "denoting the natural presence of enlightenment (bodhi) or purity",[11] and Yoga means union with the divine and refers to a spiritual path or a state of spiritual absorption. According to a book published by Sahaja Yogis, Sahaja Yoga means spontaneous and born with you meaning that the kundalini is born within us and can be awakened spontaneously, without effort.[5]

The term 'Sahaja Yoga' goes back at least to the 15th Century Indian mystic Kabir[12] and has also been used to refer to Surat Shabd Yoga.[13] Sahaja can also mean 'comfortable', 'natural', or 'uncomplicated' in Hindi.

History

[edit]Before starting Sahaja Yoga, Srivastava had a reputation as a spiritual healer.[7]: 211–212 In 1970, with a small group of devotees around her, she began spreading her message of Sahaja Yoga in India. As she moved with her husband to London, UK, she continued her religious activities there, and the movement grew and spread throughout Europe, by the mid-80's reaching North America. In 1989, Shri Mataji made her first trip to Russia and Eastern Europe.[14] She did not charge for her classes, insisting that her lesson was a birthright which should be freely available to all.[15] As of 2021, Sahaja Yoga has centers in at least 69 countries.[16]

Beliefs and practices

[edit]The movement claims Sahaja Yoga is different from other yoga/meditations because it begins with self realization through kundalini awakening rather than as a result of performing kriya techniques or asanas. This self realization is said to be made possible by the presence of Srivastava often through a photograph of her.[5] The teachings, practices and beliefs of Sahaja Yoga are mainly Hindu-based, with a predominance of elements from mystical traditions, as well as local customs of India.[7][3] There are however elements of Christian origin, such as the eternal battle between good and evil.[7][3] References to a variety of other religious, spiritual, mystical as well as modern scientific frameworks are also interwoven in Srivastava's teachings, although to a lesser degree.[7][3]

Religious sociologist Judith Coney[17] has reported facing a challenge in getting behind what she called "the public facade" of Sahaja Yoga.[3]: 214 She described Sahaja yogis as adopting a low profile with uncommitted individuals to avoid unnecessary conflict.[18]

Coney observed that the movement tolerates a variety of world views and levels of commitment with some practitioners choosing to remain on the periphery.[3]

Kundalini

[edit]Within the Indian mystic tradition, kundalini awakening has long been a much sought-after goal that was thought rare and hard to attain.[7] Sahaja Yoga is distinctive in claiming to offer a quick and easy path to such an awakening.[7]

Meditation

[edit]Meditation is one of the foundational rituals within Sahaja Yoga.[3]: 71 The technique taught emphasises the state of "thoughtless-awareness" that is said to be achieved.[19]

Role of women

[edit]Judith Coney has written that in general, Nirmala Srivastava's vision for the role of women within Sahaja Yoga was one of "feminine domesticity and compliance".[3]: 125

Some parents of Sahaja 'yogists', analyzing Nirmala Srivastava's remarks, noted that women play a subordinate role.[10] The texts of Nirmala Srivastava say that "if you are a woman and you want to dominate, then Sahaja Yoga will have difficulty in curing you" and that women should be "docile" and "domestic".[10] Judith Coney writes that women "are valued as mothers and wives but are limited to these roles and are not encouraged to be active or powerful, except within the domestic sphere and behind the scenes".[3]: 125

Coney has observed that "Gender roles for women and men within Sahaja Yoga are clearly specified and highly segregated, and positions of authority in the group are held almost exclusively by the men".[3]: 119 Coney writes that the ideal of womanhood promoted within Sahaja Yoga draws both on the ideal wifely qualities of the goddess Lakshmi and on wider Hindu traditions. Coney believes these traditions are summed up in "The Code of Manu" which holds that woman should be honoured and adorned but kept dependent on men in the family. Women are also described in this book as "dangerous" and needing to be guarded from temptation.[3]: 121

Coney has written that Nirmala Srivastava did not display consistent views on women but gave a number of messages about the status of women. On the one hand she said women are not inferior but described the sexes as complementary. Describing the man as the head of the family, she likened the woman's status to the heart: "The head always feels he decides, but the brain always knows that is the heart one has to cater, it is the heart which is all-pervading, it is the real source of everything".[3]: 122 She regretted what she saw as the loss of respect for women in society in both the East and West. However, she viewed Western feminism suspiciously, seeing it as a "route to damnation" because it required women to deviate from what she thought was their true nature.[3]: 123

Family

[edit]Human rights lawyer Sylvie Langlaude has described the configuration of families within Sahaja Yoga as having "a distinctive image and model of childhood", noting that from birth children become familiarised with the movement's beliefs and Nirmala Srivastava's status by being closely involved in its day-to-day rituals including meditation, foot-soaking, and devotional singing. This is in line with the other religions Langlaude examined, who concluded that "almost all traditions include informal nurturing within the family and slightly more formal nurturing within a religious community", and that children "are also initiated by their parents to a number of initiation rituals and to ceremonies and festivals."[20]

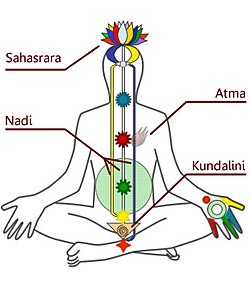

The subtle system – chakras and nadis

[edit]

Sahaja Yoga believes that in addition to our physical body there is a subtle body composed of nadis (channels) and chakras (energy centres). Nirmala Srivastava equates the Sushumna nadi with the parasympathetic nervous system, the Ida nadi with the left and the Pingala nadi with the right sides of the sympathetic nervous system. Psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar writes that Nirmala Srivastava's additions to this widespread traditional 'tantric' model include giving it a scientific, neurological veneer, an elaboration of the health aspects and an introduction of notions of traditional Christian morality.[21]

Chakras do not physically exist[22] but in a variety of ancient meditation practices they are believed to be part of the subtle body.[23]

Apostasy

[edit]In common with similar movements, most people who have left the Sahaja Yoga movement do not describe their experience as being unremittingly negative, often finding something positive they can say.[3]: 184 Nevertheless, in interviews with ex-members Judith Coney heard various complaints, including that they had experienced unwanted arranged marriage, had been dismayed by the difference between the reality of the movement and what they had expected, and had found their time in the movement frightening.[3]: 182

The ex-members who believed they had gained some form of supernatural protection from being in the movement were generally fearful of being exposed to retribution for having left, perhaps in the form of a terminal illness or fatal accident.[3]: 180

Eschatology

[edit]Within the Sahaja Yoga belief system, because we are in the final phase of the world (Kali Yuga) before the apocalypse, the Earth is rich in demons, who use satanic forces to possess people, impersonate gurus, and spread evil.[3]: 40

Judith Coney writes that Nirmala Srivastava claimed to be Adi Shakti, who had returned to earth to save it from "demonic influences."[3]: 93

Coney writes that Nirmala Srivastava identified what she saw as increased decadence in society as the work of demons "intent on dragging human beings to hell".[3]: 123

Organization

[edit]Vishwa Nirmala Dharma (trans: Universal Pure Religion, also known as Sahaja Yoga International) is the organizational part of the movement. It is a registered organization in countries such as Colombia,[24] the United States of America,[25] and Austria.[26] It is registered as a religion in Spain.[27]

Membership statistics

[edit]There are no available statistical data about Sahaja Yoga membership. In 2001, the number of core members worldwide was estimated to be 10,000, in addition to 100,000 practitioners more or less in the periphery.[6] There are varying reports about the movement's distribution worldwide. According to the Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi Sahaja Yoga World Foundation, Sahaja Yoga centers are established in over 140 countries.[28] In a news article in Indian Express published on the occasion of Srivastava's death in 2011, however, Sahaja Yoga centers were said to exist in 140 countries.[4]

International Sahaja Public School

[edit]The International Sahaja Public School in Dharamsala founded in 1990, teaches around 250 international students annually as of 1999[update], and has accepted children from the age of 6.[3]: 159

Yuvashakti

[edit]Sahaja Yoga's youth movement is called "Yuvashakti" (also "Nirmal Shakti Yuva Sangha"), from the Sanskrit words Yuva (Youth) and Shakti (Power).

The movement is active in forums such as the World Youth Conference[29] and TakingITGlobal which aim at discussing global issues, and ways of solving them.

The Yuvashakti participated in the 2000 "Civil Society & Governance Project"[30] in which they were "instrumental in reaching out to women from the poor communities and providing them with work".

Vishwa Nirmal Prem Ashram

[edit]The Vishwa Nirmala Prem Ashram is a not-for profit project by the NGO Vishwa Nirmala Dharma (Sahaja Yoga International) located in Noida, Delhi, India, opened in 2003. The ashram is a "facility where women and girls are rehabilitated by being taught meditation and other skills that help them overcome trauma".[31][32]

Funding

[edit]According to the dictates of their founder, the methods for practicing Sahaja Yoga are made available free of charge to those interested. Nevertheless, according to the official Sahaja Yoga website there is a fee for attending international pujas to cover costs.[33]

According to author David V. Barrett, "Shri Mataji neither charged for her lectures nor for her ability to give Self Realization, nor does one have to become a member of this organization. She insisted that one cannot pay for enlightenment and she continued to denounce the false self-proclaimed 'gurus' who are more interested in the seekers' purse than their spiritual ascent".[34]

Cult classification

[edit]Cult expert Jean-Marie Abgrall has written that Sahaja Yoga exhibits the classic characteristics of a cult in the way it conditions its members.[10] These include having a god-like leader, disrupting existing relationships, and promising security and specific benefits while demanding loyalty and financial support.[10] Abgrall writes that the true activities of the cult are hidden behind the projection of a positive image and an explicit statement that "Sahaja yoga is not a cult".[10]

Judith Coney has written that members "disguised some of their beliefs" from non-members.[3]: 214 Coney writes people who had left the movement welcomed the chance to talk to her as an independent researcher, but that some were fearful of reprisals if they did so, and others found their experiences too painful to revisit.[3]: 214 Most were unwilling to talk to her "on the record".[3]: 214

An "A-Z of cults" in The Guardian reported that adherents of Sahaja Yoga found a cult designation "particularly offensive" but that the movement had been plagued by accounts of children being separated from their parents and of large financial donations made to Nirmala Srivastava.[35]

In 2001, The Independent reported the allegation made by some ex-members, that Sahaja Yoga is a cult which aims to control the minds of its members.[36] Ex-members said that the organisation insists all family ties are broken and all communication with them cease, that crying children can be seen as being possessed by demons, that negative and positive vibrations need "clearing", and that being a member of the group is very expensive.[36] In 2005, The Record reported that some critics who feel that the group is a cult have started their own websites.[37]

In 2005 the Belgian State organisation IACSSO (Informatie- en Adviescentrum inzake de Schadelijke Sektarische Organisaties) issued an advisory against Sahaja Yoga.[38] The advisory categorizes Sahaja Yoga as a synretic cult ("syncretische cultus") based on the Hindu tradition, and warns that the recruitment techniques used by Sahaja Yoga pose a risk to the public in general and young people in particular.[9] Sahaja Yoga Belgium sued IACSSO and preliminary rulings were found in their favour, adjudging that Sahaja Yoga was "not a cult".[39] However, on appeal in 2011 these preliminary rulings were overturned and in a final judgement it was found that Sahaja Yoga had been unable to refute IACSSO's statements.[38]

In 2013, De Morgen reported that the Belgian Department of State Security monitors how often politicians are contacted and lobbied by organizations. The list of organizations includes Sahaja Yoga.[40]

In 2001, The Evening Standard reported that Sahaja Yoga has been "described as a dangerous cult" and "has a dissident website created by former members". The reporter, John Crace, wrote about an event he attended and noted that a Sahaja Yoga representative asked him to feel free to talk to whomever he wanted. He remarked, "Either their openness is a PR charm offensive, or they genuinely have nothing to hide." He proposed that "one of the key definitions of a cult is the rigour with which it strives to recruit new members" and concluded that there was no aggressive recruitment squeeze.[41]

David V. Barrett wrote that some former members say that they were expelled from the movement because they "resisted influence that Mataji had over their lives". According to Barrett, the movement's founder's degree of control over members' lives has given rise to concerns.[34] The Austrian Ministry for Environment, Youth and Family states that "Sahaja Yoga" regards Nirmala Srivastava as an authority who cannot be questioned.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ "Experience Your Self Realization". sahajayoga.org. Vishwa Nirmala Dharma. 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Jones, Lindsey, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA [Imprint]. ISBN 978-0-02-865997-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Coney, Judith (1999). Sahaja Yoga: Socializing Processes in a South Asian New Movement. Richmond: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1061-2.

- ^ a b "Sahaja Yoga founder Nirmala Devi is dead". The Indian Express. Express News Service. 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Srivastava, Nirmala (1989). Sahaja Yoga Book One (2nd ed.). Australia: Nirmala Yoga.[non-primary source needed][page needed]

- ^ a b c INFORM staff. "Meditation and Mindfulness". INFORM – the information network on religious movements. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sudhir Kakar (1991). Shamans, Mystics and Doctors: A Psychological Inquiry into India and its Healing Traditions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226422798.: 191

- ^ "Prophecies and Fulfillments". Sahaja Yoga Meditation. Vishwa Nirmala Dharma. 7 May 2017. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Advies van het Informatie- en Adviescentrum inzake de Schadelijke Sektarische Organisaties (IACSSO) over Sahaja Yoga" (in Dutch). IACSSO. 7 March 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f Abgrall, Jean-Marie (2000). Soul Snatchers: The Mechanics of Cults. Algora Publishing. pp. 139–144.

- ^ "Sahaja". A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-172653-8. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Ray, Nihar Ranjan (October 2000). "The concept of 'Sahaj' in Guru Nanak's theology". The Sikh Review. 48 (562). Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Soami Ji Maharaj (1934). Sar Bachan: An Abstract of the Teachings of Soami Ji Maharaj, the Founder of the Radha Soami System of Philosophy and Spiritual Science: The Yoga of the Sound Current. Translated by Sardar Sewa Singh and Julian P. Johnson. Beas, India: Radha Soami Satsang Beas.[page needed]

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2009). Encyclopedia of American religions (8th ed.). Detroit: Gale. p. 1005. ISBN 978-0-7876-6384-1.

- ^ Posner, Michael (11 March 2011). "Spiritual leader founded Sahaja yoga movement". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Sahaja Yoga Worldwide Contacts – Locate Sahaja Yoga Near You". sahajayoga.org. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Coward HG, ed. (2000). "Contributors". The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States (SUNY Series in Religious Studies. State University of New York Press. p. 289. ISBN 0791445100.

- ^ Coney, Judith (1999). Palmer, Susan J.; Hardman, Charlotte (eds.). Children in New Religions. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2620-1.

- ^ "Administrative Panel Decision 'Vishwa Nirmala Dharma a.k.a. Sahaja Yoga v. Sahaja Yoga Ex-Members Network and SD Montford' Case No. D 2001-0467". WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center. 16 June 2001.

- ^ Sylvie Langlaude (2007). "Chapter 1: Religious Children". The Right of the Child to Religious Freedom in International Law. Brill. p. 33-4.

- ^ Sudhir Kakar wrote in his book Shamans, Mystics and Doctors, "Essentially, Nirmala Srivastava's model of the human psyche is comprised of the traditional tantric and hatha yoga notions of the subtle body, with its 'nerves' and 'centers,' and fuelled by a pervasive 'subtle energy' that courses through both the human and the divine, through the body and the cosmos. Nirmala Srivastava's contributions to this ancient model are not strikingly original: as a former medical student she has sought to give it a scientific, neurological veneer; as a former faith healer, she has elaborated upon those aspects of the model that are concerned with sickness and health; as someone born into an Indian Christian family she has tried to introduce notions of traditional Christian morality into an otherwise amoral Hindu view of the psyche." See Kakar (1991), p. 196

- ^ Shermer, Michael, ed. (2002). The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 538. ISBN 978-1-57607-653-8.

- ^ Sharma, Arvind (2006). A Primal Perspective on the Philosophy of Religion. Springer Verlag. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-1-4020-5014-5.

- ^ "Registro Publico Entidades Religiosas 30-06-2004" [Public Registry of Religious Entities]. Ministry of the Interior and Justice: Republic of Colombia. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ "List of ECOSOC/Beijing and New Accredited NGOs that attended the special session of the General Assembly". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ "Austria – 2006 Report on International Religious Freedom". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor: US Dept. of State. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Religion in Spain". Sahaja Worldwide News and Announcements (SWAN). sahajayoga.org. Vishwa Nirmala Dharma. 19 July 2006. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi Sahaja Yoga World Foundation (7 May 2017). "From Nimala Srivastava to Shri Mataji". Shri Mataji: A Life Dedicated to Humanity. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Wittkamper, Jonah, ed. (2002). "Guide to the Global Youth Movement" (PDF). youthlink.org. Global Youth Action Network. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2005.

- ^ Tatke, Vinita (February 2000). "Case Study Civil Society & Governance Project". Archived from the original on 3 January 2004. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

- ^ Khanna, Arshiya (16 November 2006). "A New Childhood". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "An interview with Gisela Matzer" (PDF). Blossom Times. Vol. 1, no. 3. 31 August 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Puja/Dakshina Costs". Sahaja Worldwide Announcements and News (SWAN). sahajayoga.org. Vishwa Nirmala Dharma. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ a b Barrett, David V. (2001). The New Believers. Cassell. pp. 297–8. ISBN 0-304-35592-5.

- ^ Cornelius, Robert (14 May 1995). "A-Z of cults". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Shri who must be obeyed". The Independent. 13 July 2001. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Chadwick, John (24 July 2005). "Hundreds fill weekend with devotion, bliss". The Record. Bergen County, New Jersey. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007.

- ^ a b Torfs R, Vrielink J (2019). "State and Church in Belgium". In Robbers G (ed.). State and Church in the European Union (3rd ed.). Nomos Verlag. p. 24. doi:10.5771/9783845296265-11. ISBN 978-3-84-529626-5.

- ^ "Sahaja Yoga is geen sekte" [Sahaja Yoga is not a cult]. De Morgen (in Dutch). 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Martin, Buxant; Samyn, Steven (2 February 2013). "Staatsveiligheid houdt Wetstraat in de gaten" [State keeps an eye Wetstraat]. De Morgen (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Crace, John (18 July 2001). "Monday night with the divine mother". London Evening Standard.

- ^ Ministry for Environment, Youth and Family: Austria (1999). Sekten! Wissen schützt [Sects! Knowledge Protects]. Translated by cisar.org (2nd ed.). Vienna: Druckerei Berger. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help)

External links

[edit] Media related to Sahaja Yoga at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sahaja Yoga at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

KSF

KSF