Samaria (ancient city)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 15 min

שֹׁמְרוֹן (Hebrew) | |

Roman columns at Tel Sebastia, 2016 | |

Location within the West Bank Location within the Palestinian Territories | |

| Alternative name | السامرة (Arabic) |

|---|---|

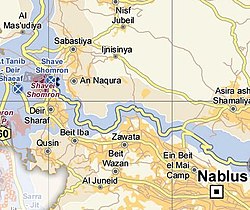

| Location | Nablus Governorate, Palestinian Territories |

| Region | Samaria (historical) |

| Coordinates | 32°16′35″N 35°11′42″E / 32.27639°N 35.19500°E |

| History | |

| Cultures | Israelite (Samaritan and Jewish) |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | Israel and Palestinian Authority |

Samaria (Hebrew: שֹׁמְרוֹן Šōmrōn; Akkadian: 𒊓𒈨𒊑𒈾 Samerina; Greek: Σαμάρεια Samareia; Arabic: السامرة as-Sāmira) was the capital city of the Kingdom of Israel between c. 880 BCE and c. 720 BCE.[1][2] It is the namesake of Samaria, a historical region bounded by Judea to the south and by Galilee to the north. After the Assyrian conquest of Israel, Samaria was annexed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and continued as an administrative centre. It retained this status in the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Achaemenid Persian Empire before being destroyed during the Wars of Alexander the Great. Later, under the hegemony of the Roman Republic and the subsequent Roman Empire, the city was rebuilt and expanded by the Jewish king Herod the Great, who also fortified it and renamed it "Sebastia" in honour of the Roman emperor Augustus.[3][4]

The ancient city's hill is where the modern Palestinian village, retaining the Roman-era name Sebastia, is situated. The local archeological site is jointly administered by Israel and the Palestinian Authority,[5] and is located on the hill's eastern slope.[6]

Etymology

[edit]Samaria's biblical name, Šōmrōn (שֹׁמְרוֹן), means "watch" or "watchman" in Hebrew.[7] The Hebrew Bible derives the name from the individual (or clan) Shemer (Hebrew: שמר), from whom King Omri (ruled 880s–870s BCE) purchased the hill in order to build his new capital city (1 Kings 16:24).[8]

In earlier cuneiform inscriptions, Samaria is referred to as "Bet Ḥumri" ("the house of Omri"); but in those of Tiglath-Pileser III (ruled 745–727 BCE) and later it is called Samirin, after its Aramaic name,[9] Shamerayin.[10] The city of Samaria gave its name to the mountains of Samaria, the central region of the Land of Israel, surrounding the city of Shechem. This usage probably began after the city became Omri's capital, but is first documented only after its conquest by Sargon II of Assyria, who turned the kingdom into the province of Samerina.[11]

Geography

[edit]

Samaria was situated north-west of Shechem, located close to a major road heading to the Sharon Plain on the coast and on another leading northward through the Jezreel Valley to Phoenicia. This location may be related to Omri's foreign policy. Strategically perched atop a steep hill, the city had a clear and good view of the nearby countryside.[12]

History

[edit]Bronze Age

[edit]The earliest settlement on the tell was dated to the Early Bronze Age.

Iron Age

[edit]First settlement

[edit]The earliest reference to a settlement at this location may be the town of Shemer, or Shamir, which according to the Hebrew Bible was the home of the judge Tola in the 12th century BC (Judges 10:1–2).[13]

Archaeological evidence suggests a small rural settlement existed in Samaria during Iron Age I (11–10th centuries BCE); remains from this period are several rock-cut installations, several flimsy walls, and typical pottery forms. Stager suggested to identify these remains with biblical Shemer's estate.[14]

Remains from the early Iron Age II (IIA) are missing or unidentified; Franklin believes this phase consisted of merely an agricultural estate.[15]

Kingdom of Israel

[edit]In the 9th and the 8th centuries BCE, Samaria was the capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel.[16]

A massive royal acropolis was built on the site during the late Iron Age II, including a casemate wall and a palatial complex considered one of the largest Iron Age structures in the Levant.[15]

According to Israel Finkelstein, the first palace at Samaria, probably built by Omri (884–873 BCE), marked the beginning of the northern Kingdom of Israel's transformation into a more complex kingdom. A later urban transformation of the capital and the kingdom, he believes, was characteristic of the more advanced phase of the Omride dynasty, probably occurring during the reign of Ahab (873–852 BCE). Finkelstein also suggested that the biblical narratives surrounding the northern Israelite kings were composed either in Samaria or Bethel. After the fall of Israel during the 8th century, this information was brought to Judah, and later found its way into the Hebrew Bible.[15]

Biblical narrative

[edit]According to the Hebrew Bible, Omri, the king of the northern kingdom of Israel, purchased the hill from its owner, Shemer, for two talents of silver, and built on its broad summit a city he named Šōmrōn (Shomron; later it became 'Samaria' in Greek), the new city replacing Tirzah as the capital of his kingdom (1 Kings 16:24).[17] As such it possessed many advantages. Omri resided here during the last six years of his reign (1 Kings 16:23).

Omri is thought to have granted the Arameans the right to "make streets in Samaria" as a sign of submission (1 Kings 20:34).

It was the only great city of Israel created by the sovereign. All the others had been already consecrated by patriarchal tradition or previous possession. But Samaria was the choice of Omri alone. He, indeed, gave to the city which he had built the name of its former owner, but its especial connection with himself as its founder is proved by the designation which it seems Samaria bears in Assyrian inscriptions, "Beth-Khumri" ("the house or palace of Omri"). (Stanley)[18]

Samaria is frequently the subject of sieges in the biblical account. During the reign of Ahab, it says that Hadadezer of Aram-Damascus attacked it along with thirty-two vassal kings, but was defeated with a great slaughter (1 Kings 20:1–21). A year later, he attacked it again, but he was utterly routed once more, and was compelled to surrender to Ahab (1 Kings 20:28–34), whose army was no more than "two little flocks of kids" compared to that of Hadadezer (1 Kings 20:27).

According to 2 Kings, Ben Hadad of Aram-Damascus laid siege to Samaria during the reign of Jehoram, but just when success seemed to be within his reach, his forces suddenly broke off the siege, alarmed by a mysterious noise of chariots and horses and a great army, and fled, abandoning their camp and all its contents. The starving inhabitants of the city feasted on the spoils from the camp. As Prophet Elisha had predicted, "a measure of fine flour was sold for a shekel, and two measures of barley for a shekel, in the gates of Samaria" (2 Kings 6–7).

Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian periods

[edit]Towards the end of the 8th century BCE, possibly in 722 BCE,[19][20][21][22] Samaria was captured by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and became an administrative center under Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian rule.[16]

Hellenistic period

[edit]Samaria was destroyed a second time by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, and again by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in 108 BCE.[23][better source needed]

Roman period

[edit]

The city was rebuilt by Herod the Great between the years 30–27 BCE.[24] According to Josephus, Herod rebuilt and expanded the city, bringing in 6,000 new inhabitants, and renamed it Sebastia (Hebrew: סבסטי) in the emperor's honor (translating the Latin epithet augustus to Greek sebastos, "venerable").[23][25][better source needed]

Archaeology

[edit]

Samaria was first excavated by the Harvard Expedition, initially directed by Gottlieb Schumacher in 1908 and then by George Andrew Reisner in 1909 and 1910; with the assistance of architect C.S. Fisher and D.G. Lyon.[26]

Reisner's dig unearthed the Samaria Ostraca, a collection of 102 ostraca written in the Paleo-Hebrew Script.[27][28]

A second expedition was known as the Joint Expedition, a consortium of 5 institutions directed by John Winter Crowfoot between 1931 and 1935; with the assistance of Kathleen Mary Kenyon, Eliezer Sukenik and G.M. Crowfoot. The leading institutions were the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Palestine Exploration Fund, and the Hebrew University.[29][30][31]

A palace regarded as one of the largest Iron Age structures in the Levant was discovered during this excavation.[15][32][7] Archeologists believe it was built during the 9th century BCE by the Omrides.[15] The palace, constructed of massive roughly dressed blocks, is comparable in size and splendor to palaces built at the same period in northern Syria. It was surrounded by official administrative structures on the west and northeast.[15] Six proto-Ionic capitals used as spolia discovered nearby may have originally adorned a monumental gateway to the palace.[15] According to Norma Franklin, there is a possibility that the tombs of Omri and Ahab are located beneath the Iron Age palace.[33] Excavations in the palace uncovered 500 pieces of carved ivory, portraying exotic animals and plants, mythological creatures, and foreign deities, among other things.[34][35] Some scholars identified those with the "palace adorned with ivory" mentioned in the Bible (1 Kings 22:39).[35] Some of the ivories are on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and in other locations across the world.[34]

In the 1960s, further small scale excavations directed by Fawzi Zayadine were carried out on behalf of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.[36]

See also

[edit]- Omrides

- Tel Jezreel

- Biblical archeology

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- List of modern names for biblical place names

References

[edit]- ^ Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R, eds. (2013-01-21). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah11208.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5.

- ^ "1 Kings 12 / Hebrew - English Bible / Mechon-Mamre". mechon-mamre.org.

- ^ Barag, Dan (1993-01-01). "King Herod's Royal Castle at Samaria-Sebaste". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 125 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1179/peq.1993.125.1.3. ISSN 0031-0328.

- ^ Dell’Acqua, Antonio (2021-09-20). "The Urban Renovation of Samaria–Sebaste of the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE: Observations on some architectural artefacts". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 154 (3): 221–243. doi:10.1080/00310328.2021.1980310. ISSN 0031-0328. S2CID 240589831.

- ^ Greenwood, Hanan (2022-08-10). "'State couldn't care less that Jewish heritage sites are being destroyed'". www.israelhayom.com. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- ^ Burgoyne, Michael Hamilton; Hawari, M. (May 19, 2005). "Bayt al-Hawwari, a hawsh House in Sabastiya". Levant. 37. Council for British Research in the Levant, London: 57–80. doi:10.1179/007589105790088913 (inactive 18 July 2025). S2CID 162363298. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Tappy, Ron E. (1992-01-01). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria. Volume 1: Early Iron Age through the Ninth Century BCE. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004369665. ISBN 978-90-04-36966-5.

- ^ "This Side of the River Jordan; On Language", Forward, Philologos, 22 September 2010.

- ^ Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). . The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- ^ Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey, eds. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. pp. 788–789. ISBN 9780865543737. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

Sargon ... named the new province, which included what formerly was Israel, Samerina. Thus the territorial designation is credited to the Assyrians and dated to that time; however, "Samaria" probably long before alteratively designated Israel when Samaria became the capital.

- ^ Rocca, Samuel (2010). The fortifications of ancient Israel and Judah, 1200-586 BC. Adam Hook. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-84603-508-1. OCLC 368020822.

- ^ Boling, R.G. (1975). Judges: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. (Anchor Bible, Volume 6a), Page 185

- ^ Stager, Lawrence E. (1990). "Shemer's Estate". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (277/278): 93–107. doi:10.2307/1357375. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357375. S2CID 163576333.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finkelstein, Israel (2013). The Forgotten Kingdom: the archaeology and history of Northern Israel. pp. 65–66, 73, 78, 87–94. ISBN 978-1-58983-911-3. OCLC 880456140.

- ^ a b Pummer, Reinhard (2019), "Samaria", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–3, doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah11208.pub2, ISBN 978-1-4443-3838-6, S2CID 241784278, retrieved 2021-12-22

- ^ Omri, king of the northern ten tribes of Israel, built the city and settled his men in the Old City, in accordance with the account relayed in the Hebrew Bible (1 Kings 16:24). Compare Josephus, Antiquities (Book viii, chapter xii, verse 5)

- ^ Easton, Matthew George (1897). . Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

- ^ Schipper, Bernd U. (2021-05-25). "Chapter 3 Israel and Judah from 926/925 to the Conquest of Samaria in 722/720 BCE". A Concise History of Ancient Israel. Penn State University Press. pp. 34–54. doi:10.1515/9781646020294-007. ISBN 978-1-64602-029-4.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sebastia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ Pummer, Reinhard (2019-12-20). "Samaria". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah11208.pub2. ISBN 9781405179355. S2CID 241784278.

- ^ Hennessy, J. B. (1970-01-01). "Excavations at Samaria-Sebaste, 1968". Levant. 2 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1179/007589170790216981. ISSN 0075-8914.

- ^ a b Sebaste, Holy Land Atlas Travel and Tourism Agency.

- ^ Segal, Arthur (2017). "Samaria-Sebaste. Portrait of a polis in the Heart of Samaria". Études et Travaux (Institut des Cultures Méditerranéennes et Orientales de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences). XXX (30): 409. doi:10.12775/EtudTrav.30.019. ISSN 2084-6762.

- ^ Josephus, De Bello Judaico (Wars of the Jews) i.xxi.§2

- ^ Reisner, G. A.; C.S. Fisher, and D.G. Lyon (1924). Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1908–1910. (Vol 1: Text [1], Vol 2: Plans and Plates [2]), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

- ^ Hebrew Ostraca from Samaria, David G. Lyon, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan., 1911), pp. 136–143, quote: "The script in which these ostraca are written is the Phoenician, which was widely current in antiquity. It is very different from the so-called square character, in which the existing Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible are written."

- ^ Noegel, p.396

- ^ Crowfoot, J. W.; G.M. Crowfoot (1938). Early Ivories from Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste. reports of the work of the Joint expedition in 1931–1933 and of the British expedition in 1935; no. 2). London: Palestine Exploration Fund, ISBN 0-9502279-0-0

- ^ Crowfoot, J. W.; K.M. Kenyon and E.L. Sukenik (1942). The Buildings at Samaria (Samaria-Sebaste. Reports of the work of the joint expedition in 1931–1933 and of the British expedition in 1935; no.1). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ^ Crowfoot, J. W.; K.M. Kenyon and G.M. Crowfoot (1957). The Objects from Samaria (Samaria; Sebaste, reports of the work of the joint expedition in 1931;1933, and of the British expedition in 1935; no.3). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (2011-11-01). "Observations on the Layout of Iron Age Samaria". Tel Aviv. 38 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1179/033443511x13099584885303. ISSN 0334-4355. S2CID 128814117.

- ^ Franklin, Norma (2007). "Tombs of the Kings of Israel". Biblical Archaeology Review. 33 (4): 26–34.

- ^ a b Biblical Archaeology Society Staff (2017). "The Samaria Ivories—Phoenician or Israelite?". Strata in Biblical Archaeology Review.

- ^ a b Pienaar, D. N. (2008-12-01). "Symbolism in the Samaria ivories and architecture". Acta Theologica. 28 (2): 48–68. hdl:10520/EJC111399.

- ^ Zayadine, F (1966). "Samaria-Sebaste: Clearance and Excavations (October 1965 – June 1967)". Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, vol. 12, pp. 77–80

Further reading

[edit]- "Excavations at Samaria". The Harvard Theological Review. 1 (4): 518–519. 1908. doi:10.1017/S001781600000674X. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1507225. S2CID 193255908.

- Lyon, David G. (1911). "Hebrew Ostraca from Samaria". The Harvard Theological Review. 4 (1): 136–143. doi:10.1017/S0017816000006970. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1507545. S2CID 163915013.

- Reisner, George Andrew; Fisher, Clarence Stanley; Lyon, David Gordon (1924). Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1908-1910. Vol. I: Text. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Reisner, George Andrew; Fisher, Clarence Stanley; Lyon, David Gordon (1924). Harvard Excavations at Samaria, 1908-1910. Vol. II: Plans and Plates. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Crowfoot, J.W.; Crowfoot, G. M. (1938). Samaria-Sebaste 2: Early ivories from Samaria. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Sukenik, E.L. (1940). "Arrangements for the Cult of the Dead in Ugarit and Samaria". In Vincent, L.-H. (ed.). Mémorial Lagrange: Cinquantenaire del'École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem. Paris: Gabalda. pp. 59–65.

- Crowfoot, J.W.; Kenyon, K.M.; Sukenik, E.L. (1942). Samaria-Sebaste 1: The Buildings at Samaria. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Crowfoot, J. W; Crowfoot, Grace Mary; Kenyon, Kathleen M. (1957). Samaria-Sebaste 3: The objects from Samaria. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. OCLC 648989.

- Bach, Robert (1958). "Zur Siedlungsgeschichte des Talkessels von Samaria". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 74 (1): 41–54. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27930564.

- Parrot, André (1958). Samaria, the capital of the kingdom of Israel. Translated by Hooke, S. H. London: SCM Press.

- Tadmor, Hayim (1958). "The Campaigns of Sargon II of Assur: A Chronological-Historical Study". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 12 (1): 22–40. doi:10.2307/1359580. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359580. S2CID 164043881.

- Wright, G.E. (1959). "Israelite Samaria and Iron Age Chronology". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 155 (155): 13–29. doi:10.2307/1355671. JSTOR 1355671. S2CID 164050660.

- Wright, G.E. (1959). "Samaria". The Biblical Archaeologist. 22 (3): 67–78. doi:10.2307/3209132. JSTOR 3209132. S2CID 224788149.

- Hennessy, J.B. (1970). "Excavations at Samaria-Sebaste, 1968". Levant. 2: 1–21. doi:10.1179/007589170790216981.

- Tadmor, Miriam (1974). "Fragments of an Achaemenid Throne from Samaria". Israel Exploration Journal. 24 (1): 37–43. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27925437.

- Grayson, A.K. (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles Texts from Cuneiform Sources 5. New York. pp 69–87.

- Mallowan, M. E. L. (1978). "Samaria and Calah Nimrud: Conjunctions in History and Archaeology". In Moorey, R.; Parr, P. (eds.). Archaeology in the Levant. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. pp. 155–163.

- Timm, S. (1982). Die Dynastie Omri. Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte Israels im 9. Jahrhun- dert vor Christus. Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 124. Göttingen.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Na'aman, Nadav (1990). "The Historical Background to the Conquest of Samaria (720 BC)". Biblica. 71 (2): 206–225. ISSN 0006-0887. JSTOR 42611103.

- Stager, Lawrence E. (1990). "Shemer's Estate". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (277/278): 93–107. doi:10.2307/1357375. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357375. S2CID 163576333.

- Hayes, John H.; Kuan, Jeffrey K. (1991). "The Final Years of Samaria (730-720 BC)". Biblica. 72 (2): 153–181. ISSN 0006-0887. JSTOR 42611173.

- Becking, Bob (1992). The fall of Samaria: an historical and archaeological study. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 9789004096332.

- Tappy, R. E. (1992). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria: Vol. I, Early Iron Age through the Ninth Century BCE. Harvard Semitic Studies 44. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press.

- Beach, Eleanor Ferris (1993). "The Samaria Ivories, Marzeaḥ, and Biblical Text". The Biblical Archaeologist. 56 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2307/3210252. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210252. S2CID 166018412.

- Albenda, Pauline (1994). "Some Remarks on the Samaria Ivories and Other Iconographic Resources". The Biblical Archaeologist. 57 (1): 60. doi:10.2307/3210398. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210398. S2CID 187293603.

- Galil, Gershon (1995). "The Last Years of the Kingdom of Israel and the Fall of Samaria". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 57 (1): 52–65. ISSN 0008-7912. JSTOR 43722052.

- Ussishkin, David (1997). "Jezreel, Samaria and Megiddo: Royal Centres of Omri and Ahab". Congress Volume, Cambridge 1995: Vetus Testamentum, Supplements 66. pp. 351–364. doi:10.1163/9789004275904_019. ISBN 978-90-04-10687-1.

- Eshel, Hanan (1999). "The Rulers of Samaria during the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BCE / מושלי מדינת שמרין במאות הה'–הד' לפסה"נ". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה. כו: 8–12. ISSN 0071-108X. JSTOR 23629878.

- Younger, K. Lawson (1999). "The Fall of Samaria in Light of Recent Research". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 61 (3): 461–482. ISSN 0008-7912. JSTOR 43723630.

- Finkelstein, Israel (2000). "Omride Architecture". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 116 (2): 114–138. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931645.

- Gerson, Stephen N. (2001). "Fractional Coins of Judea and Samaria in the Fourth Century BCE". Near Eastern Archaeology. 64 (3): 106–121. doi:10.2307/3210840. ISSN 1094-2076. JSTOR 3210840. S2CID 156640795.

- Tappy, R. E. (2001). The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria: Vol. II, The Eighth Century BCE. Harvard Semitic Studies 50. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Franklin, Norma (2001). "Masons' Marks from the 9th Century BCE Northern Kingdom of Israel. Evidence of the Nascent Carian Alphabet?". Kadmos. 40 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1515/kadm.2001.40.2.97. S2CID 162295146.

- Magness, Jodi (2001). "The Cults of Isis and Kore at Samaria-Sebaste in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods". The Harvard Theological Review. 94 (2): 157–177. doi:10.1017/S0017816001029029. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 3657401. S2CID 162272677.

- Franklin, Norma (2003). "The Tombs of the Kings of Israel: Two Recently Identified 9th-Century Tombs from Omride Samaria". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 119 (1): 1–11. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931708.

- Franklin, Norma (2004). "Samria from the bedrock to the Omride palace". Levant. 36: 189–202. doi:10.1179/lev.2004.36.1.189. S2CID 162217071.

- Ussishkin, David (2007). "Megiddo and Samaria: A Rejoinder to Norma Franklin". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 348 (348): 49–70. doi:10.1086/BASOR25067037. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 25067037. S2CID 163737898.

- Mahieu, Bieke (2008). "The Foundation Year of Samaria-Sebaste and its Chronological Implications". Ancient Society. 38: 183–196. doi:10.2143/AS.38.0.2033275. ISSN 0066-1619. JSTOR 44080267.

- Park, Sung Jin (2012). "A New Historical Reconstruction of the Fall of Samaria". Biblica. 93 (1): 98–106. ISSN 0006-0887. JSTOR 42615082.

- Wetherill, R.; Tappy, Ron. E. (2016). "The Archaeology of the Ostraca House at Israelite Samaria: Epigraphic Discoveries in Complicated Contexts". The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 70. American Schools of Oriental Research. JSTOR 26539223.

- Yezerski, Irit (2017). "The Iron Age II S-Tombs at Samaria-Sebaste, Rediscovered". Israel Exploration Journal. 67 (2): 183–208. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 26740628.

External links

[edit]- Samaria (city), biblewalks

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Samaria". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Samaria". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Vailhé, S. (1913). "Samaria". Catholic Encyclopedia.

KSF

KSF