Saterland Frisian language

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 18 min

| Saterland Frisian | |

|---|---|

| Seeltersk | |

| Native to | Germany |

| Region | Saterland |

| Ethnicity | Saterland Frisians |

Native speakers | 2,000 (2015)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | Germany |

| Regulated by | Seelter Buund in Saterland/Seelterlound (unofficial) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | stq |

| Glottolog | sate1242 |

| ELP | Saterfriesisch |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACA-ca[2] |

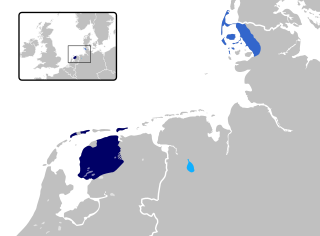

Present-day distribution of the Frisian languages in Europe:

Saterland Frisian | |

Saterland Frisian, also known as Sater Frisian, Saterfrisian or Saterlandic (Seeltersk [ˈseːltɐsk]), spoken in the Saterland municipality of Lower Saxony in Germany, is the last living dialect of the East Frisian language. It is closely related to the other Frisian languages: North Frisian, spoken in Germany as well, and West Frisian, spoken in the Dutch province of Friesland.

Classification

[edit]From a diachronical perspective, Saterland Frisian is an Emsfrisian dialect of the East Frisian language. Emsfrisian used to be spoken in the western half of the East Frisian peninsula and in the Ommelanden. The other East Frisian dialect group was the Weserfrisian, formerly spoken from the eastern half of the East Frisian peninsula to beyond the Weser.

Together with West Frisian and North Frisian it belongs to the Frisian branch of the Germanic languages. The three Frisian languages evolved from Old Frisian. Among the living Frisian dialects, the one spoken in Heligoland (called Halunder) is the closest to Saterland Frisian.[3]: 418 The closest language other than Frisian dialects is English.

Frisian and English are often grouped together as Anglo-Frisian languages. Today, English, Frisian and Lower German, sometimes also Dutch, are grouped together under the label North Sea Germanic. Low German, which is closely related to Saterland Frisian, lacks many North Sea Germanic features already from the Old Saxon period onward.[4] In turn, Saterland Frisian has had prolonged close contact with Low German.[5]: 32 [6]

History

[edit]Settlers from East Frisia, who left their homelands around 1100 A.D. due to natural disasters, established the Frisian language in the Saterland. Since the sparse population at the time of their arrival spoke Old Saxon, the Frisian language of the settlers came into close contact with Low German.[5]: 30-32

In East Frisia, the assimilation of Frisian speakers into the Low German speaking population was well under way in the early 16th century. The dialect of the Saterland persisted mostly due to geography: As the Saterland is surrounded by bogland, its inhabitants had few contacts with adjacent regions. The villages built on sandy hills were basically like islands. Until the 19th century, the settlement area was almost exclusively reachable by boat via the river Sagter Ems (Seelter Äi). The exception being walking on frozen or dried out bogland during times of extreme weather.[7][6]

Politically, the land did not belong to the County of East Frisia, which came into existence in the 15th century, but changed hands frequently until it became part of County of Oldenburg. The resulting border was not merely political, but also denominational, as the Saterland was recatholicized.[6] The Saterland was linguistically and culturally different from Oldenburg, too. This led to further isolation.

Colonialization of the bogland, the construction of roads and railways led to the Saterland being less isolated. Still, Saterfrisian managed, because most of the community living in the Saterland continued to use the language. This common linguistic area was disturbed following World War II. German repatriates from Eastern Europe were settled in the Saterland, leading to Standard German gradually replacing Saterfrisian. While the predicted language death in the late 20th century did not happen, and the number of speakers being stable, the Saterfrisian speaking community nowadays make up only a minority of those living in the Saterland.[8]: 46 [9]

Geographic distribution

[edit]

Today, estimates of the number of speakers vary slightly. Saterland Frisian is spoken by about 2,250 people, out of a total population in Saterland of some 10,000; an estimated 2,000 people speak the language well, slightly fewer than half of those being native speakers.[nb 1] The great majority of native speakers belong to the older generation; Saterland Frisian is thus a seriously endangered language. It might, however, no longer be moribund, as several reports suggest that the number of speakers is rising among the younger generation, some of whom raise their children in Saterlandic.

Current revitalization efforts

[edit]Since about 1800, Sater Frisian has attracted the interest of a growing number of linguists. Media coverage sometimes argues that this linguistic interest, particularly the work of Marron Curtis Fort, helped preserve the language and revive interest among speakers in transmitting it to the next generation.[11] During the last century, a small literature developed in it. Also, the New Testament of the Bible was translated into Sater Frisian by Fort, who was himself a Christian.[12]

Children's books in Saterlandic are few, compared to those in German. Margaretha (Gretchen) Grosser, a retired member of the community of Saterland, has translated many children's books from German into Saterlandic.[6] A full list of the books and the time of their publication can be seen on the German Wikipedia page of Margaretha Grosser.

Recent efforts to revitalize Saterlandic include the creation of an app called "Kleine Saterfriesen" (Little Sater Frisians) on Google Play. According to the app's description, it aims at making the language fun for children to learn, as it teaches them Saterlandic vocabulary in many different domains (the supermarket, the farm, the church). There have been more than 500 downloads of the app since its release in December 2016, according to statistics on Google Play Store.[13]

The language remains capable of producing neologisms as evidenced by a competition during the Covid-19 pandemic to create a Saterfrisian word for anti-Covid face masks held in late 2020 / early 2021[14] which resulted in the term "Sküüldouk" being adopted with face masks having the Saterfrisian sentence "Bäte dusse Sküüldouk wädt Seeltersk boald!" ("Under this face mask, Saterfrisian is spoken") written on them gaining some local popularity.[15]

Official Status

[edit]The German government has not committed significant resources to the preservation of Sater Frisian. Most of the work to secure the endurance of this language is therefore done by the Seelter Buund ("Saterlandic Alliance"). Along with North Frisian and five other languages, Sater Frisian was included in Part III of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages by Germany in 1998.[16]

Dialects

[edit]There are three fully mutually intelligible dialects, corresponding to the three main villages of the municipality of Saterland: Ramsloh (Saterlandic: Roomelse), Scharrel (Schäddel), and Strücklingen (Strukelje).[3]: 419 The Ramsloh dialect now somewhat enjoys a status as a standard language, since a grammar and a word list were based on it.

Phonology

[edit]The phonology of Saterland Frisian is regarded as very conservative linguistically, as the entire East Frisian language group was conservative with regards to Old Frisian.[17] The following tables are based on studies by Marron C. Fort.[3]: 411–412 [8]: 64–65

Vowels

[edit]

Monophthongs

[edit]The consonant /r/ is often realised as a vowel [ɐ̯ ~ ɐ] in the syllable coda depending on its syllable structure.

Short vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | fat (fat) |

| ä | /ɛ/ | Sät (a while) |

| e | /ə/ | ze (they) |

| i | /ɪ/ | Lid (limb) |

| o | /ɔ/ | Dot (toddler) |

| ö | /œ/ | bölkje (to shout) |

| u | /ʊ/ | Buk (book) |

| ü | /ʏ/ | Djüpte (depth) |

Semi-long vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ie | /iˑ/ | Piene (pain) |

| uu | /uˑ/ | kuut (short) |

Long vowels:

| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| aa | /aː/ | Paad (path) |

| ää | /ɛː/ | tään (thin) |

| ee | /eː/ | Dee (dough) |

| íe | /iː/ | Wíek (week) |

| oa | /ɔː/ | doalje (to calm) |

| oo | /oː/ | Roop (rope) |

| öö | /øː/ | röögje (rain) |

| öä | /œː/ | Göäte (gutter) |

| üü | /yː/ | Düwel (devil) |

| úu | /uː/ | Múus (mouse) |

Diphthongs

[edit]| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ai | /aːi/ | Bail (bail) |

| au | /aːu/ | Dau (dew) |

| ääu | /ɛːu/ | sääuwen (self) |

| äi | /ɛɪ/ | wäit (wet) |

| äu | /ɛu/ | häuw (hit, thrust) |

| eeu | /eːu/ | skeeuw (skew) |

| ieu | /iˑu/ | Grieuw (advantage) |

| íeu | /iːu/ | íeuwen (even, plain) |

| iu | /ɪu/ | Kiuwe (chin) |

| oai | /ɔːɪ/ | toai (tough) |

| oi | /ɔy/ | floitje (to pipe) |

| ooi | /oːɪ/ | swooije (to swing) |

| ou | /oːu/ | Bloud (blood) |

| öi | /œːi/ | Böije (gust of wind) |

| uui | /uːɪ/ | truuije (to threaten) |

| üüi | /yːi/ | Sküüi (gravy) |

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | x | h |

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Approximant | (w) | l | j | ||

Today, voiced plosives in the syllable coda are usually terminally devoiced. Older speakers and a few others may use voiced codas.[18]

Plosives

[edit]| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | /p/ | Pik (pitch) | |

| t | /t/ | Toom (bridle) | |

| k | /k/ | koold (cold) | |

| b | /b/ | Babe (father) | Occasionally voiced in syllable coda |

| d | /d/ | Dai (day) | May be voiced in syllable coda by older speakers |

| g | /ɡ/ | Gäize (goose) | A realization especially used by younger speakers instead of [ɣ]. |

Fricatives

[edit]| Grapheme | Phoneme(s) | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| g | /ɣ, x/ | Gäize (goose), Ploug (plough) | Voiced velar fricative, unvoiced in the syllable coda and before an unvoiced consonant. Younger speakers show a tendency towards using the plosive [ɡ] instead of [ɣ], as in German, but that development has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| f | /f, v/ | Fjúur (fire) | Realised voicedly by a suffix: ljoof - ljowe (dear - love) |

| w | /v/ | Woater (water) | Normally a voiced labio-dental fricative like in German, after u it is however realised as bilabial semi-vowel [w] (see below). |

| v | /v, f/ | iek skräive (I scream) | Realised voicelessly before voiceless consonants: du skräifst (you scream) |

| s | /s, z/ | säike (to seek), zuuzje (to sough) | Voiced [z] in the syllable onset is unusual for Frisian dialects and also rare in Saterlandic. There is no known minimal pair s - z so /z/ is probably not a phoneme. Younger speakers tend to use [ʃ] more, for the combination of /s/ + another consonant: in fräisk (Frisian) not [frɛɪsk] but [fʀɛɪʃk]. That development, however, has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| ch | /x/ | truch (through) | Only in syllable nucleus and coda. |

| h | /h/ | hoopje (to hope) | Only in onset. |

Other consonants

[edit]| Grapheme | Phoneme | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| m | /m/ | Moud (courage) | |

| n | /n/ | näi (new) | |

| ng | /ŋ/ | sjunge (to sing) | |

| j | /j/ | Jader (udder) | |

| l | /l/ | Lound (land) | |

| r | /r/, [r, ʀ, ɐ̯, ɐ] | Roage (rye) | Traditionally, a rolled or simple alveolar [r] in onsets and between vowels. After vowels or in codas, it becomes [ɐ]. Younger speakers tend to use a uvular [ʀ] instead. That development, however, has not yet been reported in most scientific studies. |

| w | /v/, [w] | Kiuwe (chin) | As in English, it is realised as a bilabial semivowel only after u. |

Morphology

[edit]Personal pronouns

[edit]The subject pronouns of Saterland Frisian are as follows:[19]

| singular | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| first person | iek | wie | |

| second person | du | jie | |

| third person | masculine | hie, er | jo, ze (unstr.) |

| feminine | ju, ze (unstr.) | ||

| neuter | dät, et, t | ||

The numbers 1–10 in Saterland Frisian are as follows:[3]: 417

| Saterland Frisian | English |

|---|---|

| aan (m.)

een (f., n.) |

one |

| twäin (m.)

two (f., n.) |

two |

| träi (m.)

trjo (f., n.) |

three |

| fjauer | four |

| fieuw | five |

| säks | six |

| sogen | seven |

| oachte | eight |

| njúgen | nine |

| tjoon | ten |

Numbers one through three in Saterland Frisian vary in form based on the gender of the noun they occur with.[3]: 417 In the table, "m." stands for masculine, "f." for feminine, and "n." for neuter.

For the purposes of comparison, here is a table with numbers 1–10 in 4 West Germanic languages:

| Saterland Frisian | Low German | German | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| aan (m.)

een (f., n.) |

een | eins | one |

| twäin (m.)

two (f., n.) |

twee | zwei | two (and the old masculine 'twain') |

| träi (m.)

trjo (f., n.) |

dree | drei | three |

| fjauer | veer | vier | four |

| fieuw | fief | fünf | five |

| säks | söss | sechs | six |

| sogen | söben | sieben | seven |

| oachte | acht | acht | eight |

| njúgen | negen | neun | nine |

| tjoon | teihn | zehn | ten |

Vocabulary

[edit]The Saterlfrisian language preserved some lexical peculiarities of East Frisian, such as the verb reke replacing the equivalent of German: geben in all contexts (e.g. Daach rakt et Ljude, doo deer baale …,[20] German: Doch gibt es Leute, die da sprechen; 'Yet there are people, who speak') or kwede ('to say') compare English 'quoth'. In Old Frisian, quetha and sedza existed (Augustinus seith ande queth …,[21] 'Augustinus said and said'). Another word, common in earlier forms of Western Germanic, but survived only in East Frisian is Soaks meaning 'knife' (comp. Seax).

Orthography

[edit]Saterland Frisian became a written language relatively recently. German orthography cannot adequately represent the vowel rich Frisian language. Until the mid-20th century, scholars researching it developed their own orthography. The poet Gesina Lechte-Siemer, who published poems in Saterfrisian since the 1930s, adopted a proposal by the cultural historian Julius Bröring.[22]

In the 1950s Jelle Brouwer, professor in Groningen, an orthography based on the Dutch one, which failed to gain widespread acceptance. The West Frisian Pyt Kramer, who did research in Saterfrisian, developed a phonemic orthography.[23] The American linguist Marron Curtis Fort used Brouwer's Dutch-based orthography as a basis for his own proposal.[24] The most notable difference between the two orthographies is the way long vowels are represented. Kramer proposes that long vowels always be spelled with a double vowels (baale 'to speak'), while Fort maintains, that long vowels in open syllables be spelled with a single vowels, as Frisian vowels in open syllables are always long (bale 'to speak'). Both proposals use almost no diacritics, apart from Fort's use of acutes to differentiate long vowels from semi-long ones.

So far, no standard has evolved. Those projects tutored by Kramer use his orthography while Fort published his works in his orthography, which is also recognized by the German authorities. Others use a compromise.[25] This lack of standards leads to the village Scharrel being spelled Schäddel on its town sign instead of the currently used Skäddel.

In the media

[edit]Nordwest-Zeitung, a German-language regional daily newspaper based in Oldenburg, Germany, publishes occasional articles in Saterland Frisian. The articles are also made available on the newspaper's Internet page, under the headline Seeltersk.

As of 2004, the regional radio station Ems-Vechte-Welle broadcasts a 2-hour program in Saterland Frisian and Low German entitled Middeeges.[6] The program is aired every other Sunday from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. The first hour of the program is usually reserved for Saterland Frisian. The program usually consists of interviews about local issues between music. The station can be streamed live though the station's Internet page.

Sample text

[edit]Below is a snippet of the New Testament in Saterland Frisian, published in 2000 and translated by Marron Curtis Fort:[24]

Dut aal is geskäin, dät dät uutkume skuul, wät die Here truch dän Profeet kweden häd; |

This all has happened, so that it would come true, what the Lord through the prophet has said; |

The Lord's Prayer:[24]

Uus Foar in dän Hemel, din Nome wäide heliged, |

A preview of the first stanza of the Saterlied (Seelter Läid), which is considered to be the regional anthem of Saterland:[5]

Ljude rakt et fuul un Lounde, |

There are many people and countries |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A number of 6,370 speakers is cited by Fort,[3]: 410 a 1995 poll counted 2,225 speakers; [9] Ethnologue refers to a monolingual population of 5,000, but this number originally was not of speakers but of persons who counted themselves ethnically Saterland Frisian.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Saterland Frisian at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- ^ "r-s" (PDF). The Linguasphere Register. p. 252. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Fort, Marron Curtis (2001). "Das Saterfriesische" [The Saterland Frisian language]. In Munske, Horst (ed.). Handbuch des Friesischen [Handbook of the Frisian language] (in German). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 3-484-73048-X.

- ^ Nielsen, Hans Frede (2001). "Frisian and the Grouping of the Older Germanic Languages". In Munske, Horst (ed.). Handbuch des Friesischen [Handbook of the Frisian language]. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 3-484-73048-X.

- ^ a b c Klöver, Hanne (1998). Spurensuche im Saterland: Ein Lesebuch zur Geschichte einer Gemeinde friesischen Ursprungs im Oldenburger Münsterland (in German). Norden: Soltau-Kurier. ISBN 3-928327-31-3. OCLC 246014591.

- ^ a b c d e Peters, Jörg (2020). "Saterfriesisch" [Saterland Frisian language]. In Beyer, Rahel; Plewnia, Albrecht (eds.). Handbuch der Sprachminderheiten in Deutschland [Handbook of linguistic minorities in Germany] (in German) (1 ed.). Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag. pp. 139–171. ISBN 978-3-8233-8261-4. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Hoche, Johann Gottfried (1977) [1800]. Reise durch Osnabrück und Niedermünster in das Saterland, Ostfriesland und Groeningen [Voyage through Osnabrück and Neumünster into the Saterland, East Frisia and Groeningen] (in German) (reprint ed.). Leer: Theodor Schuster. p. 130. ISBN 3-7963-0137-1.

- ^ a b Fort, Marron Curtis (1980). Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch [Dictionary of the Saterland Frisian language] (in German). Hamburg: Buske.

- ^ a b Stellmacher, Dieter (1998). Das Saterland und das Saterländische [The Saterland and Saterlandic] (in German). Oldenburg: Oldenburgische Landschaft Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89598-567-6.

- ^ "Saterfriesisch". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Keller, Martina (15 January 2015). "Eine Sprache für drei Dörfer" [A language spoken in just three villages]. Deutsche Welle (in German).

- ^ Keller, Martina (28 September 2009). "Der letzte Saterfriese" [The last Saterland Frisian]. Deutsche Welle (in German).

- ^ "Kleine Saterfriesen - Apps on Google Play". play.google.com. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- ^ "Was heißt "Mund-Nasen-Schutz" auf Saterfriesisch?" [How does "facemask" translate into Saterland Frisian?]. NDR (in German). 27 December 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Bäte dusse Sküüldouk wädt Seeltersk boald! Alles verstanden?" [Bäte dusse Sküüldouk wädt Seeltersk boald! Got it?]. NDR (in German). 21 February 2021. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Nationale Minderheiten, Minderheitensprachen und die Regionalsprache Niederdeutsch in Deutschland [National minorities, minority languages and the regional language Lower German in Germany] (PDF) (in German) (4 ed.), Berlin: Bundesministerium für Inneres, Bau und Sicherheit, November 2020, retrieved 29 November 2022

- ^ Versloot, Arjen (2001). "Grundzüge Ostfriesischer Sprachgeschichte" [Outlines of East Frisian linguistic history]. In Munske, Horst (ed.). Handbuch des Friesischen [Handbook of the Frisian language] (in German). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. ISBN 3-484-73048-X..

- ^ a b c Peters, Jörg (2017). "Saterland Frisian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 49 (2): 223–230. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000226. S2CID 232348873.

- ^ Howe, Stephen (1996). The Personal Pronouns in the Germanic Languages (1 ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 192. ISBN 9783110819205. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Lechte-Siemer, Gesina (1977). Ju Seelter Kroune (in Saterland Frisian). Rhauderfehn: Ostendorp Verlag.

- ^ Buma, Jan Wybren; Ebel, Wilhelm, eds. (1967). Emsiger Recht. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ Bröring, Julius (1897). Das Saterland: Eine Darstellung von Land, Leben, Leuten in Wort und Bild [The Saterland: A depiction of the land, customes and people]. Vol. 1. Oldenburg: Stalling.

Bröring, Julius (1901). Das Saterland: Eine Darstellung von Land, Leben, Leuten in Wort und Bild. Vol. 2. Oldenburg: Stalling. - ^ Kramer, Pyt (1982). Kute Seelter Sproakleere = Kurze Grammatik des Saterfriesischen [A short Grammar of Saterfrisian] (in German). Rhauderfehn: Ostendorp Verlag. pp. 5–8. ISBN 978-3-921516-35-5.

- ^ a b c Fort, Marron Curtis (2000). Dät Näie Tästamänt un do Psoolme in ju aasterlauwersfräiske Uurtoal fon dät Seelterlound, Fräislound, Butjoarlound, Aastfräislound un do Groninger Umelounde [The New Testament and the Psalms in the East Low Franconian language of Saterland, Frisia, Butjadingen, East Frisia and Ommelande] (in Saterland Frisian). Oldenburg: Bis-Verlag. ISBN 3-8142-0692-4. OCLC 174542094.

- ^ Slofstra, Bouke; Hoekstra, Eric; Leppers, Tessa (2021). Grammatik des Saterfriesischen (PDF). Fryske Akademie. p. 9.

Further reading

[edit]- Fort, Marron C. (1980): Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch. Hamburg: Helmut Buske.

- Fort, Marron C. (2001) Das Saterfrisische. In Munske, Horst Haider (ed.), Handbuch des Friesischen, 409–422. Berlin: DeGruyter Mouton

- Kramer, Pyt (1982): Kute Seelter Sproakleere - Kurze Grammatik des Saterfriesischen. Rhauderfehn: Ostendorp.

- Peters, Jörg (2017). "Saterland Frisian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 49 (2): 223–230. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000226. S2CID 232348873.

- Slofstra, Bouke; Hoekstra, Eric (2022). Sprachlehre des Saterfriesischen (PDF). Fryske Akademy.

- Stellmacher, Dieter (1998): Das Saterland und das Saterländische. Oldenburg.

External links

[edit]- Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch (German)

- Näie Seelter Siede

- Seeltersk Kontoor (German)

- Seelter Buund

KSF

KSF