Science and technology in Germany

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

Science and technology in Germany has a long and illustrious history, and research and development efforts form an integral part of the country's economy. Germany has been the home of some of the most prominent researchers in various scientific disciplines, notably physics, mathematics, chemistry and engineering.[2] Before World War II, Germany had produced more Nobel laureates in scientific fields than any other nation, and was the preeminent country in the natural sciences.[3][4] Germany is currently the nation with the 3rd most Nobel Prize winners, 115.

The German language, along with English and French, was one of the leading languages of science from the late 19th century until the end of World War II.[5][6] After the war, because so many scientific researchers' and teachers' careers had been ended either by Nazi Germany which started a brain drain, the denazification process, the American Operation Paperclip and Soviet Operation Osoaviakhim which exacerbated the brain drain in post-war Germany, or simply losing the war, "Germany, German science, and German as the language of science had all lost their leading position in the scientific community."[7]

Today, scientific research in the country is supported by industry, the network of German universities and scientific state-institutions such as the Max Planck Society and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. The raw output of scientific research from Germany consistently ranks among the world's highest.[8] Germany was declared the most innovative country in the world in the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index and was ranked 9th in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[9]

Institutions

[edit]

The Deutsches Museum, 'German Museum' of Masterpieces of Science and Technology in Munich is one of the largest science and technology museums in the world in terms of exhibition space, with about 28,000 exhibited objects from 50 fields of science and technology.[10][11]

The Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, 'Federal Ministry of Education and Research' (BMBF) is a supreme authority of the Federal Republic of Germany for science and technology. The headquarter of the Federal Ministry is located in Bonn, the second office in Berlin. It was founded in 1972 as Federal Ministry of Research and Technology (BMFT) to promote basic research, applied research and technological development.[12]

Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (German: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK, previous BMWi)

Foundations

[edit]- Alexander von Humboldt Foundation

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research association)

- German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), promoting international exchange of scientists and students)

- The Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, 'Fritz Thyssen Foundation' supports young scientists and research projects. It was founded in 1959 and is located in Cologne. The purpose of the foundation, with an endowment capital of €542.4 million,[13] is to promote science at scientific universities and research institutes, primarily in Germany, under particular consideration on young scientists.[14]

National science libraries

[edit]- German National Library of Economics (ZWB), Kiel & Hamburg

- German National Library of Medicine (ZB MED), Cologne & Bonn

- German National Library of Science and Technology (TIB), Hannover

Research organizations

[edit]

- Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (complex systems und large-scale research), Bonn & Berlin

- Fraunhofer Society (applied research and mission oriented research, Munich)

- Leibniz Association (fundamental and applied research), Berlin

- Max Planck Society (fundamental research), Munich

- Gesellschaft für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik ("Society of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics"), Dresden

- The Hasso Plattner Institute (HPI), officially: Hasso Plattner Institute for Digital Engineering gGmbH, is a privately financed IT institute and, together with the University of Potsdam, forms the Digital Engineering Faculty. It is located in Potsdam-Babelsberg and researches practical and applied topics in digital technologies. Its founder and namesake is SAP founder Hasso Plattner.

Prize committees

[edit]- The Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize is granted to ten scientists and academics every year. With a maximum of €2.5 million per award it is one of highest endowed research prizes in the world.[15] The prize and the mentioned organization above is named after the German polymath and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), who was a contemporary and competitor of Isaac Newton (1642–1727).

- The Bunsen–Kirchhoff Award is a prize for "outstanding achievements" in the field of analytical spectroscopy. The prize is named in honor of chemist Robert Bunsen and physicist Gustav Kirchhoff (→ Physics).

- The Helmholtz Prize is awarded with €20,000 every two to three years to European scientists for scientific and technological research in metrology.[16]

Scientific fields

[edit]

The global spread of the printing press with movable types and an oil-based ink was a process that began around 1440 with the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1400–1468) and continued until the introduction of printing based on this procedure in all parts of the world in the 19th century, thus creating the conditions for the dissemination of generally accessible scientific publications emerging to the revolution of science.[17]

Scientific Revolution

[edit]Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was one of the originators of the Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. He was an astronomer, physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher[21] He advocated the idea of a heliocentric model of the Solar System, which can be traced back to the theories of the ancient Greek astronomers Aristarchus of Samos and Seleucus of Seleucia, as well as to the 16th-century astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), whose main work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, 'On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres' about the heliocentric model was first published by Johannes Petreius (c. 1497–1550) and likely the polymath Johannes Schöner (1477–1547) in the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg in 1543. In March 1600, Kepler became assistant to the astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) at the court of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague, Kingdom of Bohemia. After Brahe's death in October of the next year, Kepler succeeded him as imperial mathematician and court astronomer (until 1627).[22]

Johannes Kepler discovered the laws according to which planets are moving around the Sun, who were called Kepler's laws after him. With his introduction to calculating with logarithms, Kepler contributed to the spread of this type of calculation. In mathematics, a numerical method for calculating the volume of wine barrels with integrals was named former Kepler's barrel rule.[24] He made optics to a subject of scientific investigation and confirmed the discoveries made with the telescope by his Italian contemporary Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). He worked on the theory of the telescope and invented the refracting astronomical or Keplerian telescope,[25] which involved a considerable improvement over the Galilean telescope.[26] Kepler also made the invention of the valveless gear pump, because a mine owner needed a device to pump water out of his mine.[27]

Physics

[edit]

Otto von Guericke (1602–1686) was a scientist, inventor, mathematician and physicist from Magdeburg. He is best known for his experiments on air pressure using the Magdeburg hemispheres. With the invention of the vacuum pump he laid the foundation of vacuum technology.

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736) was a physicist and inventor of measuring instruments from Danzig. The temperature unit degrees Fahrenheit (°F) was named after him.

Gustav Kirchhoff (1824–1887) was a physicist from Königsberg who made a particular contribution to the study of electricity. Today, Kirchhoff is best known for Kirchhoff's circuit laws, and for introducing the concept of a black body, which contributed to the emergence of quantum mechanics. However, Kirchhoff's circuit laws were discovered as early as 1833 by Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) during his experiments on electricity. With Robert Bunsen (1811–1899) he developed flame spectroscopy in 1859, which can be used to detect chemical elements with high specificity.[28] Bunsen was a chemist from Göttingen, and together with Kirchhoff discovered the elements caesium and rubidium in 1861. He perfected the Bunsen burner, which is named after him, and invented the Bunsen cell and a grease-spot photometer.

The work of Albert Einstein (1879–1955), best known for developing the theory of relativity,[29] and Max Planck (1858–1947), he is known for the Planck constant, was crucial to the foundation of modern physics, which Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) and Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) developed further.[30] They were preceded by such key physicists as Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787–1826), who discovered the Fraunhofer lines in spectroscopy, and Hermann von Helmholtz (1857–1894), among others. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923) discovered X-rays in 1895, an accomplishment that made him the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901[31] and eventually earned him an element name, roentgenium. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz's (1857–1894) work in the domain of electromagnetic radiation were pivotal to the development of modern telecommunication; the unit of frequency was named in his honor "Hertz".[32] Mathematical aerodynamics was developed in Germany, especially by Ludwig Prandtl.

Karl Schwarzschild (1873–1916) was an astrophysicist from Frankfurt am Main. He was professor and director of the Göttingen Observatory from 1901 to 1909. There he was able to work together with scientists like David Hilbert (1862–1943) and Hermann Minkowski (1864–1909). Schwarzschild works on relativity provided the first exact solutions to the field equations of Albert Einstein's general relativity – one for an uncharged, non-rotating spherically symmetric body and one for a static isotropic void around a solid body. Schwarzschild did some fundamental works on classical black holes. This is why some properties of black holes got their name, namely the Schwarzschild metric and the Schwarzschild radius. The center of a non-rotating, uncharged black hole is called the Schwarzschild singularity.

Paul Forman in 1971 argued the remarkable scientific achievements in quantum physics were the cross-product of the hostile intellectual atmosphere whereby many scientists rejected Weimar Germany and Jewish scientists, revolts against causality, determinism and materialism, and the creation of the revolutionary new theory of quantum mechanics. The scientists adjusted to the intellectual environment by dropping Newtonian causality from quantum mechanics, thereby opening up an entirely new and highly successful approach to physics. The "Forman Thesis" has generated an intense debate among historians of science.[33][34]

Deutsche Physik

[edit]

The so-called Deutsche Physik, 'German physics' was a movement that some German physicists hold during the Nazi period, which mixed physics with racist views. They rejected new discoveries in physics as being too theoretical and advocated a stronger emphasis on empirical evidence. This physics was influenced by anti-Semitic ideas that were widespread in the polarized political climate of the Weimar Republic. In addition, some leading theoretical physicists at that time were of Jewish descent. Leading representatives of this ideology were the Bavarian physicist Johannes Stark (1874–1957, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1919) and the German-Hungarian physicist Philipp Lenard (1862–1947, Nobel Prize winner of 1905).[35] Notably, the latter labeled Albert Einstein's contributions to science as Jewish physics.[36]

Chemistry

[edit]

Georgius Agricola gave chemistry its modern name. He is generally referred to as the father of mineralogy and as the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[37][38]

Justus von Liebig (1803–1873) made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is one of the principal founders of organic chemistry.[39]

At the start of the 20th century, Germany garnered fourteen of the first thirty-one Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, starting with Hermann Emil Fischer (1852–1919) in 1902 and until Carl Bosch (1874–1940) and Friedrich Bergius (1884–1949) in 1931.[31]

Otto Hahn (1879–1968) was a pioneer of radioactivity and radiochemistry with the discovery of nuclear fission together with the Austrian scientist Lise Meitner (1878–1968) and Fritz Strassmann (1902–1980) in 1938, the scientific and technological basis for the utilization of atomic energy.

The bio-chemist Adolf Butenandt (1903–1995) independently worked out the molecular structure of the primary male sex hormone of testosterone and was the first to successfully synthesize it from cholesterol in 1935.

Engineering

[edit]

Germany has been the home of many famous inventors and engineers, such as Johannes Gutenberg, who is credited with the invention of movable type printing press in Europe; Hans Geiger, the creator of the Geiger counter; and Konrad Zuse, who built the first electronic computer.[40] German inventors, engineers and industrialists such as Zeppelin, Siemens, Daimler, Otto, Wankel, Von Braun and Benz helped shape modern automotive and air transportation technology including the beginnings of space travel.[41][42] The engineer Otto Lilienthal laid some of the fundamentals for the science of aviation.[43]

The physicist and optician Ernst Abbe (1840–1905) founded in the 19th century together with the entrepreneurs Carl Zeiss (1840–1905) and Otto Schott (1851–1935) the basics of modern Optical engineering and developed many optical instruments like microscopes and telescopes. Since 1899 he was the sole owner of the Carl Zeiss AG and played a decisive role of setting up the enterprise Jenaer Glaswerk Schott & Gen (today Schott AG). These enterprises are very successful worldwide up to present time (21st century).

The engineer Rudolf Diesel (1858–1913) was the inventor of an internal combustion engine, the Diesel engine. He first published his idea of an engine with a particularly high level of efficiency in 1893 in his work Theorie und Konstruktion eines rationellen Wärmemotors, 'Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor'.[44] After 1893, he succeeded in building such an engine in a laboratory at the Augsburg Machine Factory (now MAN). Through his patents registered in many countries and his public relations work, he gave his name to the engine and the associated Diesel fuel.

In the 1930s the electrical engineers Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) and Max Knoll (1897–1969) developed at the "Technische Hochschule zu Berlin" the first electron microscope.[45]

Manfred von Ardenne (1907–1997) was a scientist, engineer and active as a researcher primarily in applied physics and is the originator of around 600 inventions and patents in radio and television technology, electron microscopy, nuclear, plasma and medical technology.

Biological and earth sciences

[edit]

Martin Waldseemüller (c. 1472/1475–1520) and Matthias Ringmann (1482–1511) were cartographers of the Renaissance. In 1507 they created the first world map on which the land masses in the west of the Atlantic Ocean were named "America" after Amerigo Vespucci.[46] The Waldseemüller map of 1507 has been part of the UNESCO World Documentary Heritage since 2005.

Emil Behring, Ferdinand Cohn, Paul Ehrlich, Robert Koch, Friedrich Loeffler and Rudolph Virchow, six key figures in microbiology, were from Germany. Alexander von Humboldt's (1769–1859) work as a natural scientist and explorer was foundational to biogeography, he was one of the outstanding scientists of his time and a shining example for Charles Darwin.[47][48][49] Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) was an eclectic Russian-born botanist and climatologist who synthesized global relationships between climate, vegetation and soil types into a classification system that is used, with some modifications, to this day.[50] The Frankfurt surgeon, botanist, microbiologist, and mycologist Anton de Bary (1831–1888) laid one of the fundamentals of the plant pathology and was one of the discoverer of the symbiosis of organisms.

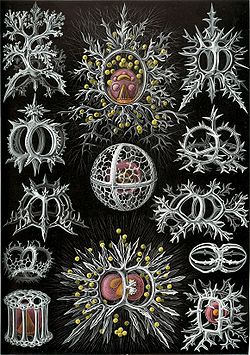

Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) discovered, described and named thousands of new species, mapped a tree of life relating all life forms and coined many terms in biology, for example ecology and phylum. His published artwork of different lifeforms includes over 100 detailed, multi-colour illustrations of animals and sea creatures, collected in his Kunstformen der Natur, 'Art Forms of Nature', an international bestseller and a book that would go on to influence the Art Nouveau (Jugendstil, 'youth style'). But Haeckel was also a promoter of scientific racism[51] and embraced the idea of Social Darwinism.

Alfred Wegener (1880–1930), a similarly interdisciplinary scientist, was one of the first people to hypothesize the theory of continental drift that was later developed into the overarching geological theory of plate tectonics.

Psychology

[edit]Wilhelm Wundt is credited with the establishment of psychology as an independent empirical science through his construction of the first laboratory at the University of Leipzig in 1879.[52]

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute founded by Oskar and Cécile Vogt was among the world's leading institutions in the field of brain research.[53] They collaborated with Korbinian Brodmann to map areas of the cerebral cortex.

After the National Socialistic laws banning Jewish doctors in 1933, the fields of neurology and psychiatry faced a decline of 65% of its professors and teachers. The research shifted to a 'Nazi neurology', with subjects such as eugenics or euthanasia.[53]

Humanities

[edit]

Besides natural sciences, German researchers have added much to the development of humanities.

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280) was a polymath, philosopher, lawyer, natural scientist, theologian, Dominican and Bishop of Regensburg. His great, diverse knowledge earned him the name Magnus ("the Great"), the title of Doctor of the Church and the honorary title of doctor universalis.[54]

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist, "the prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology".[55] Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890) was a wealthy businessman and a devotee of the historicity of places mentioned in the works of Homer and an archaeological excavator of Hisarlik (since 1871), now presumed to be the site of Troy, along with the Mycenaean sites Mycenae and Tiryns. Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903) is widely counted as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century; his work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. Max Weber (1864–1920) was together with Karl Marx (1818–1883) among the most important theorists of the development of modern Western society and is regarded as one of the founder of the Sociology.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was a philosopher of the Enlightenment and professor of logic and metaphysics in Königsberg. Kant is one of the most important representatives of Western philosophy. His work Critique of Pure Reason marks a turning point in the history of philosophy and the beginning of modern philosophy. Kant is best known for the categorical imperative, the fundamental principle of moral action from his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals: "Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

While Kant was one of the first philosopher of German idealism, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) is one of the most influential and last representative of it. His philosophy seeks to interprete the whole of reality in its variety of manifestations, including historical development, in a coherent, systematic and definitive manner. It is divided into "logic", "natural philosophy" and "Phenomenology of Geist", which also includes a philosophy of history. His thinking also became the starting point for numerous other movements in the theory of science, sociology, history, theology, politics, jurisprudence and art theory, and it also influenced other areas of culture and intellectual life.

Contemporary examples are the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, the Egyptologist Jan Assmann, the sociologist Niklas Luhmann, the historian Reinhart Koselleck and the legal historian Michael Stolleis. In order to promote the international visibility of research in these fields a new prize, Geisteswissenschaften International, 'Humanities international', was established in 2008; it serves the translation of studies of humanities into English.[56]

Warfare

[edit]

Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831) was a Prussian Generalmajor, army reformer, military scientist and ethicist. Clausewitz became known through his unfinished major work Vom Kriege, which deals with the problem of the theory of war. His theories on strategy, tactics and philosophy had a major influence on the military theory in all Western countries and are still taught at military academies until today. They are also used in business management and marketing. The most used quotation is the statement from his masterpiece: "War is the continuation of policy with other means."[57]

Oswald Boelcke was the progenitor of air-to-air combat tactics, fighter squadron organization, early-warning systems, and the German air force; he has been dubbed "the father of air combat".[58][59] From his first victories, the news of his success instructed and motivated both his fellow fliers and the German public. It was at his instigation that the Imperial German Air Service founded its Jastaschule (Fighter School) to teach his aerial tactics. The promulgation of his Dicta Boelcke set tactics for the German fighter force. The concentration of fighter airplanes into squadrons gained Germany air supremacy on the Western Front, and was the basis for their wartime successes.[60]

Personalities

[edit]-

Hildegard of Bingen, considered by scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.[61]

-

Georgius Agricola gave chemistry its modern name. Generally referred to as the father of mineralogy and the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[37][38]

-

Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press, named the most important invention of the second millennium.[62]

-

Johannes Kepler, one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method, natural and modern science.[63][21][64]

-

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, founder of modern archaeology,[65] father of the discipline of art history[66] and father of Neoclassicism.[67]

-

Carl Friedrich Gauss, referred to as one of the most important mathematicians of all time.[68]

-

Robert Koch, one of the fathers of microbiology,[69] medical bacteriology[70][71] and one of the founders of modern medicine.

-

Otto Lilienthal, who has been referred to as the "father of aviation"[75][76][77] or "father of flight".[78]

-

Karl Ferdinand Braun, who has been called one of the fathers of television, radio telegraphy and who built the first semiconductor, inaugurating the field of electronics.[79][80][81][82][83]

-

Fritz Haber invented the Haber–Bosch process. It is estimated that it provides the food production for nearly half of the world's population.[84][85] Haber has been called one of the most important scientists and chemists in human history.[86][87][88]

-

Albert Einstein, who has been called the greatest physicist of all time and one of the fathers of modern physics.[89]

-

Wernher von Braun, who co-developed the V-2 rocket, the first artificial object to travel into space. Described by others as the "father of space travel",[92] the "father of rocket science",[93] or the "father of the American lunar program".[94]

See also

[edit]- German inventors and discoverers

- German inventions and discoveries

- Operation Paperclip

- Technology during World War II

- Körber European Science Prize

Notes

[edit]- ^ https://www.leopoldina.org/en/about-us/about-the-leopoldina/about-the-leopoldina

- ^ "Back to the Future: Germany – A Country of Research". German Academic Exchange Service. 23 February 2005. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ^ National Science Nobel Prize shares 1901–2009 by citizenship at the time of the award and by country of birth. From J. Schmidhuber (2010), Evolution of National Nobel Prize Shares in the 20th Century Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine at arXiv:1009.2634v1

- ^ Swedish academy awards. ScienceNews web edition, Friday, 1 October 2010: http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/63944/title/Swedish_academy_awards

- ^ "Nobel Prize: How English beat German as language of science". BBC News. 11 October 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Garcia-Navarro, Lulu (8 January 2017). "How English Came To Be The Dominant Language In Science Publications". NPR. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Hammerstein, Notker (2004). "Epilogue: Universities and War in the Twentieth Century". In Rüegg, Walter (ed.). A History of the University in Europe: Volume Three, Universities in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (1800–1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 637–672. ISBN 9781139453028. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Top 20 Country Rankings in All Fields, 2006, Thomson Corporation, retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2024). Global Innovation Index 2024. Unlocking the Promise of Social Entrepreneurship. Geneva. p. 18. doi:10.34667/tind.50062. ISBN 978-92-805-3681-2. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The New York Times Travel Guide". The New York Times. 10 August 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

This is the largest technological museum of its kind in the world.

- ^ Website Deutsches Museum

- ^ BMBF: Federal Ministry of Education and Research, access-date: 20. Juni 2024

- ^ "Liste der größten Stiftungen" (in German). stiftungen.org. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Fritz Thyssen Stiftung. Retrieved 19 June 2024

- ^ "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize". DFG. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Association of German Research Centres: Doctoral Award – Helmholtz – Association of German Research Centres, access-date: 11. Juni 2024

- ^ "the Printing Revolution". Lumen Learning. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "DPMA | Johannes Kepler".

- ^ "Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times | NASA". Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You – Timeline – Johannes Kepler".

- ^ a b "Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times". NASA. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ photoniques: Famous optician: Johannes Kepler, doi: 10.1051/2017S212. Retrieved: 19. Juni 2024

- ^ Juan Valdez, The Snow Cone Diaries: A Philosopher's Guide to the Information Age, p 367.

- ^ J. V. Field (April 1999). "Johannes Kepler – Biography". London: University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You – Timeline – Johannes Kepler

- ^ Di Liscia, Daniel A. (17 September 2021). "Johannes Kepler (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ "Johannes Kepler's 450th birthday". German Patent and Trade Mark Office. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

Kepler invented a largely maintenance-free pump for him, the principle of which is still used today in oil pumps in car engines

- ^ Marshall, James L.; Marshall, Virginia R. (2008). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Mineral Waters and Spectroscopy" (PDF). The Hexagon: 42–48. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Physics: past, present, future". Physics World. 12 June 1999. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Roberts, J. M. The New Penguin History of the World, Penguin History, 2002. Pg. 1014. ISBN 0-14-100723-0

- ^ a b "The Alfred B. Nobel Prize Winners, 1901-2003". The World Almanac and Book of Facts. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2007 – via History Channel.

- ^ "Historical figures in telecommunications". International Telecommunication Union. 14 January 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Paul Forman, "Weimar Culture, Causality, and Quantum Theory, 1918–1927: Adaptation by German Physicists and Mathematicians to a Hostile Intellectual Environment", Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 3 (1971): 1–116

- ^ Helge Kragh, Quantum generations: a history of physics in the twentieth century (2002) ch 10

- ^ "Lenard's Nobel lecture (1906)" (PDF). Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ "How 2 Pro-Nazi Nobelists Attacked Einstein's "Jewish Science". Scientific American. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Georgius Agricola". University of California – Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b Rafferty, John P. (2012). Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 10. ISBN 9781615305445

- ^ Jackson, Catherine Mary (December 2008). Analysis and Synthesis in Nineteenth-Century Organic Chemistry (PDF) (PhD). University of London. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Horst, Zuse. "The Life and Work of Konrad Zuse". Everyday Practical Electronics (EPE) Online. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ "Automobile". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ The Zeppelin Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- ^ Bernd Lukasch. "From Lilienthal to the Wrights". Anklam: Otto-Lilienthal-Museum. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor at Google Books

- ^ Hawkes, Peter W. (1 July 1990). "Ernst Ruska". Physics Today. 43 (7): 84–85. Bibcode:1990PhT....43g..84H. doi:10.1063/1.2810640. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ Hébert, John R. (September 2003). "The Map That Named America". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ The Natural History Legacy of Alexander von Humboldt (1769 to 1859) Humboldt Field Research Institute and Eagle Hill Foundation. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- ^ a b "The Father of Ecology". 19 February 2020.

- ^ a b "The Forgotten Father of Environmentalism". The Atlantic. 23 December 2015.

- ^ * Allaby, Michael (2002). Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate. New York: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4071-0.

- ^ Hawkins, Mike (1997). Social Darwinism in European and American Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 140.

- ^ Kim, Alan. Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 16 June 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007

- ^ a b European neurology [1] German Neurology and the 'Third Reich'. By Michael Martin, Heiner Fangerau, and Axel Karenberg

- ^ "St. Albertus Magnus". Britannica. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ Boorstin, Daniel J. (1983). The Discoverers. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-72625-0.

- ^ GINT. "Geisteswissenschaften International Nonfiction Translators Prize". boersenverein.de. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Clausewitz, Carl von (1984) [1832]. Howard, Michael; Paret, Peter (eds.). On War [Vom Krieg]. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-691-01854-6.

- ^ Franks, Bailey & Guest (1993), p. 76.

- ^ Head (2016), Cover, title page, 40, 186.

- ^ Head (2016), pp. 168–170.

- ^ Jöckle, Clemens (2003). Encyclopedia of Saints. Konecky & Konecky. p. 204.

- ^ "Gutenberg, Man of the Millennium". 1,000+ People of the Millennium and Beyond. 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012.

- ^ "DPMA | Johannes Kepler".

- ^ "Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You - Timeline - Johannes Kepler".

- ^ Boorstin, 584

- ^ Robinson, Walter (February 1995). "Introduction". Instant Art History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 240. ISBN 0-449-90698-1.

The father of official art history was a German named Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68).

- ^ "Winckelmann – Humanistic Assoc. Great Europe".

- ^ "Carl Friedrich Gauss | Biography, Discoveries, & Facts | Britannica".

- ^ Fleming, Alexander (1952). "Freelance of Science". British Medical Journal. 2 (4778): 269. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4778.269. PMC 2020971.

- ^ Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). "Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate". Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (11): 854–855. PMID 19037548.

- ^ Gradmann, Christoph (2006). "Robert Koch and the white death: from tuberculosis to tuberculin". Microbes and Infection. 8 (1): 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.004. PMID 16126424.

- ^ "Karl Benz: Father of the Automobile". YouTube. 11 February 2020.

- ^ "The Father of automobile gave us Mercedes Benz and Merc gave us fascinating facts. Check out a few here! - ET Auto".

- ^ Fanning, Leonard M. (1955). Carl Benz: Father of the Automobile Industry. New York: Mercer Publishing.

- ^ "DPMA | Otto Lilienthal". Dpma.de. 2 December 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "In perspective: Otto Lilienthal". Cobaltrecruitment.co.uk. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Germany's first "flying man"". The Economist. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Otto Lilienthal, the Glider King". SciHi BlogSciHi Blog. 23 May 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ https://www.uni-marburg.de/de/uniarchiv/unijournal/urvater-der-kommunikationsgesellschaft.pdf

- ^ "The Scientist who World War I wrote out of history". 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Mit Nobelpreisträger Karl Ferdinand Braun begann das Fernsehzeitalter". Die Welt. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Peter Russer (2009). "Ferdinand Braun — A pioneer in wireless technology and electronics". 2009 European Microwave Conference (EuMC). pp. 547–554. doi:10.23919/EUMC.2009.5296324. ISBN 978-1-4244-4748-0. S2CID 34763002.

- ^ "Siegeszug des Fernsehens: Vor 125 Jahre kam die Braunsche Röhre zur Welt". Geo.de. 15 February 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (2004). Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 156. ISBN 9780262693134.

- ^ Flavell-While, Claudia. "Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch – Feed the World". www.thechemicalengineer.com. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ "The Man Who Killed Millions and Saved Billions". YouTube. 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Seven Billion Humans: The World Fritz Haber Made". 2 November 2011.

- ^ "Fritz Haber's Experiments in Life and Death".

- ^ "Physics: past, present, future". Physics World. 6 December 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (15 May 2019) [First published 2006 at inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa050298.htm]. "Biography of Konrad Zuse, Inventor and Programmer of Early Computers". thoughtco.com. Dotdash Meredith. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Konrad Zuse earned the semiofficial title of 'inventor of the modern computer'[who?]

- ^ "Who is the Father of the Computer?". computerhope.com.

- ^ "von Braun, Wernher: National Aviation Hall of Fame". Nationalaviation.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ "A Guide to Wernher von Braun's Life". Apollo11space.com. December 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ de la Garza, Alejandro (18 July 2019). "How Historians Are Reckoning With the Former Nazi Who Launched America's Space Program". Time.

References

[edit]- Franks, Norman; Bailey, Frank; Guest, Russell (1993). Above the Lines: A Complete Record of the Aces and Fighter Units of the German Air Service, Naval Air Service and Flanders Marine Corps 1914–1918. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-73-1.

- Head, R. G. (2016). Oswald Boelcke: Germany's First Fighter Ace and Father of Air Combat. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-910690-23-9.

- Competing Modernities: Science and Education, Kathryn Olesko and Christoph Strupp. (A comparative analysis of the history of science and education in Germany and the United States)

- English section of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research's website

- Germany's science and research landscape

- Articles and dossiers about Research and Technology in Germany, Goethe-Institut

- Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Schenkenhofer, J. (2018). Internationalization strategies of hidden champions: lessons from Germany. Multinational Business Review.

KSF

KSF![Hildegard of Bingen, considered by scholars to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany.[61]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Hildegard_von_Bingen.jpg/120px-Hildegard_von_Bingen.jpg)

![Georgius Agricola gave chemistry its modern name. Generally referred to as the father of mineralogy and the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[37][38]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/63/Georgius_Agricola.jpg/120px-Georgius_Agricola.jpg)

![Johannes Gutenberg, inventor of the printing press, named the most important invention of the second millennium.[62]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Gutenberg.jpg/120px-Gutenberg.jpg)

![Johannes Kepler, one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy, the scientific method, natural and modern science.[63][21][64]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/JKepler.jpg/120px-JKepler.jpg)

![Johann Joachim Winckelmann, founder of modern archaeology,[65] father of the discipline of art history[66] and father of Neoclassicism.[67]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Johann_Joachim_Winckelmann_%28Raphael_Mengs_after_1755%29.jpg/120px-Johann_Joachim_Winckelmann_%28Raphael_Mengs_after_1755%29.jpg)

![Alexander von Humboldt, seen as father of ecology and of environmentalism.[48][49]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Stieler%2C_Joseph_Karl_-_Alexander_von_Humboldt_-_1843.jpg/120px-Stieler%2C_Joseph_Karl_-_Alexander_von_Humboldt_-_1843.jpg)

![Carl Friedrich Gauss, referred to as one of the most important mathematicians of all time.[68]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Carl_Friedrich_Gauss_1840_by_Jensen.jpg/120px-Carl_Friedrich_Gauss_1840_by_Jensen.jpg)

![Robert Koch, one of the fathers of microbiology,[69] medical bacteriology[70][71] and one of the founders of modern medicine.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/RobertKoch_cropped.jpg/120px-RobertKoch_cropped.jpg)

![Carl Benz, inventor of the modern car and father of the automobile industry.[72][73][74]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Carl-Benz_coloriert.jpg/120px-Carl-Benz_coloriert.jpg)

![Otto Lilienthal, who has been referred to as the "father of aviation"[75][76][77] or "father of flight".[78]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/Otto-lilienthal.jpg/120px-Otto-lilienthal.jpg)

![Karl Ferdinand Braun, who has been called one of the fathers of television, radio telegraphy and who built the first semiconductor, inaugurating the field of electronics.[79][80][81][82][83]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/55/Ferdinand_Braun.jpg/120px-Ferdinand_Braun.jpg)

![Fritz Haber invented the Haber–Bosch process. It is estimated that it provides the food production for nearly half of the world's population.[84][85] Haber has been called one of the most important scientists and chemists in human history.[86][87][88]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1e/Fritz_Haber.png/120px-Fritz_Haber.png)

![Albert Einstein, who has been called the greatest physicist of all time and one of the fathers of modern physics.[89]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Einstein_1921_by_F_Schmutzer_-_restoration.jpg/120px-Einstein_1921_by_F_Schmutzer_-_restoration.jpg)

![Konrad Zuse, inventor of the modern computer.[90][91]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Konrad_Zuse_%281992%29.jpg/120px-Konrad_Zuse_%281992%29.jpg)

![Wernher von Braun, who co-developed the V-2 rocket, the first artificial object to travel into space. Described by others as the "father of space travel",[92] the "father of rocket science",[93] or the "father of the American lunar program".[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Wernher_von_Braun_1960.jpg/120px-Wernher_von_Braun_1960.jpg)