Second Taranaki War

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

| Second Taranaki War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of New Zealand Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Taranaki Māori | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 1,500 (including women and children) | ||||||

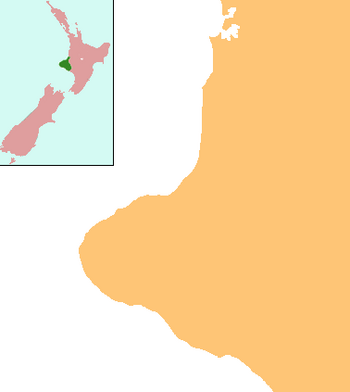

The Second Taranaki War is a term used by some historians for the period of hostilities between Māori and the New Zealand Government in the Taranaki district of New Zealand between 1863 and 1866. The term is avoided by some historians, who either describe the conflicts as merely a series of West Coast campaigns that took place between the Taranaki War (1860–1861) and Titokowaru's War (1868–69), or an extension of the First Taranaki War.[1]

The conflict, which overlapped the wars in Waikato and Tauranga, was fuelled by a combination of factors: lingering Māori resentment over the sale of land at Waitara in 1860 and government delays in resolving the issue; a large-scale land confiscation policy launched by the government in late 1863; and the rise of the so-called Hauhau movement, an extremist part of the Pai Marire syncretic religion, which was strongly opposed to the alienation of Māori land and eager to strengthen Māori identity.[2] The Hauhau movement became a unifying factor for Taranaki Māori in the absence of individual Māori commanders.

The style of warfare after 1863 differed markedly from that of the 1860-61 conflict, in which Māori had taken set positions and challenged the army to an open contest. From 1863 the army, working with greater numbers of troops and heavy artillery, systematically took possession of Māori land by driving off the inhabitants, adopting a "scorched earth" strategy of laying waste to Māori villages and cultivations, with attacks on villages, whether warlike or otherwise. As the troops advanced, the Government built an expanding line of redoubts, behind which settlers built homes and developed farms. The effect was a creeping confiscation of almost a million acres (4,000 km2) of land, with little distinction between the land of loyal or rebel Māori owners.[3]

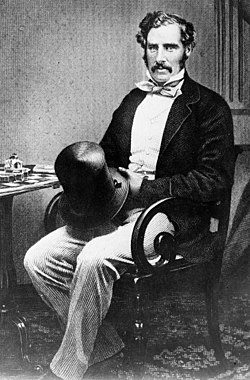

The Government's war policy was opposed by the British commander, General Duncan Cameron, who clashed with Governor Sir George Grey and offered his resignation in February 1865. He left New Zealand six months later. Cameron, who viewed the war as a form of land plunder, had urged the Colonial Office to withdraw British troops from New Zealand and from the end of 1865 the Imperial forces began to leave, replaced by an expanding New Zealand military force.[4] Among the new colonial forces were specialist Forest Ranger units, which embarked on lengthy search-and-destroy missions deep into the bush.[5][6]

The Waitangi Tribunal has argued that apart from the attack on Sentry Hill in April 1864, there was an absence of Māori aggression throughout the entire Second War, and that therefore Māori were never actually at war. It concluded: "In so far as Māori fought at all – and few did – they were merely defending their kainga, crops and land against military advance and occupation."[7]

Background and causes of the war

[edit]The conflict in Taranaki had its roots in the First Taranaki War, which had ended in March 1861 with an uneasy truce. Neither side fulfilled the terms of the truce, leaving many of the issues unresolved. Chief among those issues was (1) the legality of the sale of a 600 acres (2.4 km2) block of land at Waitara, which had sparked the first war, but Māori unrest was exacerbated by (2) a new land confiscation strategy launched by the Government and (3) the emergence of a fiery nationalist religious movement.

Disputed Waitara land

[edit]In 1861 Governor Thomas Gore Browne had promised to investigate the legitimacy of the sale of the Waitara land, but as delays continued, Taranaki and Ngāti Ruanui Māori became increasingly impatient. During the earlier war they had driven settlers off farmland at Omata and Tataraimaka, 20 km south of New Plymouth, and occupied it, claiming it by right of conquest and vowing to hold it until the Waitara land was returned to them.[2][8] On 12 March 1863, 300 men from the 57th Regiment, led by Colonel Sir Henry James Warre, marched out to Omata to retake the land and a month later, on 4 April, Browne's successor, Governor Sir George Grey, marched to Tataraimaka with troops and built a redoubt and re-occupied the land in what the Waitangi Tribunal described as a hostile act.[7] The five tribes encamped in the area – Atiawa, Taranaki, Ngatiruanui, Nga Rauru and Whanganui – promptly requested assistance from Ngāti Maniapoto and Waikato Māori to respond to what they regarded as an act of war.

In a despatch to London Grey wrote that he had failed to shake the "dogged determination" of Māori on the Waitara question. "A great part of the native race," he wrote, "may be stated to be at the present moment in arms, in a state of chronic discontent ... Large numbers of them have renounced the Queen's authority, and many of them declare openly that they have been so wronged that they will never return under it ... the great majority of them declare that if war arises from this cause, they will rise and make a simultaneous attack upon the several European settlements in the Northern Island. The reasons they urge for such proceedings are ... that the people of the Waitara, without having been guilty of any crime, were driven at the point of the sword from villages, houses, and homes which they had occupied for years. That a great crime had been committed against them. That through all future generations it will be told that their lands have been forcibly and unlawfully taken from them by officers appointed by the Queen of the United Kingdom. They argue that they have no hope of obtaining justice, that their eventual extermination is determined on; but that all that is left to them is to die like men, after a long and desperate struggle; and that the sooner they can bring that on before our preparations are further matured, and our numbers increased, the greater is their chance of success."[9]

A month later Grey began planning to return Waitara to the Māori, and on 11 May issued a proclamation renouncing all government claims to the land. But he did nothing to signal his intention and on 4 May, a week before he acted, Māori began killing British troops traversing their land. The Government declared those killings to be the outbreak of a new Taranaki war and Grey immediately wrote to the Colonial Office in London, requesting three additional regiments be sent to New Zealand.[2] He also ordered the return to New Plymouth of troops that had been moved to Auckland at the close of the earlier Taranaki hostilities, where they had been building a road southward in preparation for the invasion of the Waikato.

Land confiscations

[edit]In December 1863 the Parliament passed the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863, a piece of punitive legislation allowing unlimited confiscation of Māori land by the government, ostensibly as a means of suppressing "rebellion". Under the Act, Māori who had been "in rebellion" could be stripped of their land, which would be surveyed, divided and either given as 20 hectare farms to military settlers as a means of establishing and maintaining peace, or sold to recover the costs of fighting Māori.[3] Volunteers were enlisted from among gold miners in Otago and Melbourne for military service and a total of 479,848 hectares were confiscated in Taranaki by means of proclamations in January and September 1865.[10] Little distinction was made between the land of "rebels" and Māori loyal to the government.[7]

According to the Waitangi Tribunal, Māori recognised that the British intention was to seize the greater part of their land for European settlement through a policy of confiscation and saw that their best hope of keeping their homes, lands and status lay in taking up arms. The 1927 Royal Commission on Confiscated Land, chaired by senior Supreme Court judge Sir William Sim, concluded: "The Natives were treated as rebels and war declared against them before they had engaged in rebellion of any kind ... In their eyes the fight was not against the Queen's sovereignty, but a struggle for house and home."[3]

The rise of Hauhauism

[edit]In 1862 the so-called Hauhau Movement emerged among Taranaki Māori. The movement was an extremist part of the Pai Mārire religion that was both violent and vehemently anti-Pākehā. Adherence to the Hauhau movement, which included incantations, a sacred pole, belief in supernatural protection from bullets, and occasionally beheadings, the removal of the hearts of enemy and cannibalism, spread rapidly through the North Island from 1864, welding tribes in a bond of passionate hatred against the Pākehā.[11]

Hostilities resume

[edit]Two hui were held by Taranaki, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngā Rauru and Whanganui iwi. The first, held on 3 July 1861 at Wiriwiri near Manaia, Taranaki, resulted in most of the 1,000 people present pledging support for the Kīngitanga Movement.[12] The second, held at Kapoaiaia near Cape Egmont in July 1862 involving 600 members, involved the decision that Tataraimaka, Kaipopo, Waiwakaiho, Waitaha and Waitara were Māori lands, and that any attempt to create a road south of Waireka near Omata by European settlers would be considered an act of war.[12] By December 1862, work on the road had extended west past Waireka to Okurukuru, and by early 1863, Tamati Hone Oraukawa led a Ngāti Ruanui party north to support Taranaki iwi, if British troops re-occupied Tataraimaka.[12] Grey, while visiting the Waikato in January 1863, indicated that he intended to send troops to retake Tataraimaka.[12]

On 4 March 1863, Grey arrived at New Plymouth alongside General Duncan Cameron, Dillon Bell and Colonial Secretary Alfred Domett.[12] Between this time and early April, British troops established redoubts south and west of Omata, reaching Tataraimaka.[12] In March 1863 a group of Māori encamped on land they had seized at Tataraimaka were ousted with force by British troops in what they regarded as an act of war. The Waitangi Tribunal, in its 1996 report, also claimed the military reoccupation of Tataraimaka was a hostile act that implied war had been unilaterally resumed.[7]

Two months later, on 4 May 1863, a party of about 40 Māori ambushed a small military party of the 57th Regiment on a coastal road west of Ōakura, killing all but one of the 10 soldiers as an act of revenge. The ambush may have been planned as an assassination attempt on Grey, who regularly rode the track between New Plymouth and the Tataraimaka military post.[13] Three weeks later Māori laid another ambush near the Poutoko Redoubt, 13 km (8.1 mi) from New Plymouth, injuring a mounted officer of the 57th Regiment.[13]

The Militia and Taranaki Rifle Volunteers were called up for guard and patrol duty around New Plymouth and in June a 50-man corps of forest rangers was formed within the Taranaki Rifles by Captain Harry Atkinson to follow Māori into the bush and clear the country surrounding New Plymouth of hostile bands. The force was later expanded to two companies and named the Taranaki Bush Rangers.[13]

On 4 June the new British commander, Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, led 870 members of the 57th Regiment and 70th Regiment to attack and defeat a party of about 50 Māori still occupying the Tataraimaka block beside the Katikara River.[12] 29 Māori and one soldier from the 57th Regiment were killed in the engagement.[12] The Māori were also shelled by HMS Eclipse from about 1.5 km (0.93 mi) offshore.

On 2 October a large force of the 57th Regiment, Volunteers and militia engaged Māori near Poutoko Redoubt, Omata, 9 km south of New Plymouth. Victoria Crosses were awarded to two members of the 57th, Ensign John Thornton Down and Drummer Dudley Stagpoole, for bravery during the battle.[13][14][15]

The Hauhau movement intervenes

[edit]

In late 1863 Taranaki Māori built a strongly entrenched position at Kaitake, high on a steep ridge overlooking Ōakura. The pā was shelled in December by the 57th Regiment and through the week of 20 to 25 March 1864, the pā and nearby fortifications at Te Tutu and Ahuahu were stormed and taken by a force of 420 of the 57th, 70th and Volunteers and Militia commanded by Colonel Sir Henry James Warre, with four Armstrong guns. Cultivations of more than 2.5ha of maize, potatoes, tobacco and other crops were also found in bush clearings and destroyed. Kaitake was occupied by a company of the 57th Regiment and a company of the Otago Volunteers.[16]

Almost a fortnight later, on 6 April, a combined force of 57th Regiment and the newly formed Taranaki Military Settlers, a total of 101 men, set off from Kaitake to destroy native crops near the Ahuahu village, set amid dense bush south of Ōakura. A detachment suffered 19 casualties – seven killed and 12 wounded – after being surprised by a Māori attack as they rested without their weapons at the order of their commander, Captain P.W.J. Lloyd. Māori casualties were slight. The naked bodies of the seven dead, including Lloyd, were later recovered; all had been decapitated as part of a Hauhau rite. The mutilations were the first of a series inflicted on British and New Zealand soldiers carried out by Hauhau devotees between 1864 and 1873.[17] Lloyd had only recently arrived in New Zealand from England and his lack of caution was blamed on his unfamiliarity with Māori war tactics. The easy victory of the Māori over the numerically stronger British-led force gave a powerful impetus to the Hauhau movement. The heads of the slain soldiers were later discovered to have been taken to the east coast as part of a Pai Marire recruitment drive.[11]

Attack on Sentry Hill

[edit]

Three weeks later, on 30 April 1864, the measure of devotion to the Hauhau movement displayed itself in the reckless march by 200 warriors on the Sentry Hill redoubt, 9 km north-east of New Plymouth, in a one-sided battle that cost the lives of possibly a fifth of the Māori force. The redoubt had been built in late 1863 by Captain W. B. Messenger and 120 men of the Military Settlers on the crown of a hill that was the site of an ancient pā, and garrisoned by a detachment of 75 men from the 57th Regiment under Captain Shortt, with two Coehorn mortars. The construction of the outpost was regarded by the Atiawa as a challenge, being built close to the Māori position at Manutahi and on their land. In April 1864 a war party was formed of the best fighting men from the west coast iwi that had joined the rapidly spreading Hauhau movement.[18] In a 1920 interview with historian James Cowan, Te Kahu-Pukoro, a fighter who took part in the attack, explained: "The Pai-marire religion was then new, and we were all completely under its influence and firmly believed in the teaching of Te Ua and his apostles. Hepanaia Kapewhiti was at the head of the war-party. He was our prophet. He taught us the Pai-marire karakia (chant), and told us that if we repeated it as we went into battle the Pākehā bullets would not strike us. This we all believed."[18]

Led by Hepanaia, the warriors participated in sacred ceremonies around a pole at the Manutahi pā, with all the principal Taranaki chiefs present: Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke and Kingi Parengarenga, as well as Te Whiti and Tohu Kākahi, both of whom would later become prophets at Parihaka. The force, armed with muskets, shotguns, tomahawks and spears, marched to Sentry Hill and at 8am launched their attack, ascending the slope that led to the redoubt. Te Kahu-Pukoro recalled:

We did not stoop or crawl as we advanced upon the redoubt; we marched on upright (haere tu tonu), and as we neared the fort we chanted steadily our Pai-marire hymn.

The soldiers who were all hidden behind their high parapet, did not open fire on us until we were within close range. Then the bullets came thickly among us, and close as the fingers on my hand. The soldiers had their rifles pointed through the loopholes in the parapet and between the spaces on top (between bags filled with sand and earth), and thus could deliver a terrible fire upon us with perfect safety to themselves. There were two tiers of rifles blazing at us. We continued our advance, shooting and shouting our war-cries. Now we cried out the 'Hapa' ('Pass over') incantation which Hepanaia had taught us, to cause the bullets to fly harmlessly over us: 'Hapa, hapa, hapa! Hau, hau, hau! Pai-marire, rire, rire – hau!’ As we did so we held our right hands uplifted, palms frontward, on a level with our heads – the sign of the ringa-tu. This, we believed, would ward off the enemy's bullets; it was the faith with which we all had been inspired by Te Ua and his apostles.

The bullets came ripping through our ranks. 'Hapa, hapa!’ our men shouted after delivering a shot, but down they fell. 'Hapa!’ a warrior would cry, with his right hand raised to avert the enemy's bullets, and with a gasp – like that – he would fall dead. The tuakana (elder brother) in a family would fall with 'Hapa!’ on his lips, then the teina (younger brother) would fall; then the old father would fall dead beside them.[18]

About 34 Māori and one imperial soldier were killed.[17] Among those shot dead, at almost point-blank range, were chiefs Hepanaia, Kingi Parengarenga (Taranaki), Tupara Keina (Ngatiawa), Tamati Hone (Ngati Ruanui) and Hare Te Kokai, who had advocated the frontal attack on the redoubt. According to Cowan, the slaughter temporarily weakened the new confidence in Pai-marire, but chief prophet Te Ua had a satisfying explanation: that those who fell were to blame because they did not repose absolute faith in the karakia, or incantation.[18]

Return to Te Arei

[edit]On 8 September 1864 a force of 450 men of the 70th Regiment and Bushrangers returned to Te Arei, scene of the final British campaign of the First Taranaki War, and took the Hauhau pā of Manutahi after its inhabitants abandoned it, cutting down the niu flagstaff and destroying the palisading and whare, or homes, inside.[18] Three days later Colonel Warre led a strong force of the 70th Regiment as well as 50 kupapa ("friendly" Māori) to Te Arei and also took possession of the recently abandoned stronghold.[18]

Wanganui area campaigns

[edit]The focus of Hauhau activities shifted south with the Battle of Moutoa, on the Wanganui River, on 14 May 1864, in which Lower Wanganui kupapa routed a Hauhau war party intending to raid Wanganui. Among the 50 Hauhau killed was the prophet Matene Rangitauira, while the defending forces suffered 15 deaths.[19] Sporadic fighting between Upper and Lower Wanganui iwi continued through to 1865 and in April 1865 a combined force of 200 Taranaki Military Settlers and Patea Rangers, under Major Willoughby Brassey of the New Zealand Militia, was sent to Pipiriki, 90 km upriver from Wanganui, to establish a military post. Three redoubts were built above the river, an act that was taken by local Māori as a challenge. On 19 July a force of more than 1000 Māori began a siege of the redoubts that lasted until 30 July, with heavy exchanges of fire on most days. A relief force of 300 Forest Rangers, Wanganui Rangers and Native Contingent, as well as several hundred Lower Wanganui Māori, arrived with food and ammunition but discovered the Hauhau positions abandoned. Māori losses were between 13 and 20; the colonial force suffered four wounded.[19]

Cameron's West Coast campaign

[edit]

In January 1865 General Cameron took the field in the Wanganui district, under instructions by Governor Grey to secure "sufficient possession" of land between Wanganui and the Patea River to provide access to Waitotara. The Government claimed to have bought land at Waitotara in 1863, and in turn had sold more than 12,000 acres (49 km2) in October 1864, but the sale was disputed by some Māori, who refused to leave. A secure route from Wanganui to Patea would form a key part of the Government's strategy for a thoroughfare between Wanganui and New Plymouth, with redoubts and military settlements to protect it along the way.[7]

Cameron's campaign became notable for its caution and slow pace, and sparked an acrimonious series of exchanges between Governor Grey and Cameron, who developed a distaste for the operations against Māori, viewing it as a war of land plunder[4] and explaining the campaign could not deliver the "decisive blow" that might induce the Māori to submit.[2] Cameron considered that the British army did most of the fighting and suffered most of the casualties in order to enable settlers to take Māori land. Many of his soldiers also had great admiration for the Māori, for their courage and chivalrous treatment of the wounded.[20] Cameron offered his resignation to Grey on 7 February and left New Zealand in August.[4]

Cameron's march from Wanganui, with about 2000 troops, mainly the 57th Regiment, began on 24 January and came under daylight attack that day and the next from Hauhau forces led by Patohe while camped on an open plain at Nukumaru, suffering more than 50 casualties and killing about 23 Māori. The Hauhau warriors were part of a contingent of 2000 based at Weraroa pā, near Waitotara, who were determined to halt Cameron's march northward. Pai-Mārire chief prophet Te Ua Haumēne was also at the pā, but took no part in the fighting.[4] Cameron's force, by then boosted to 2300, moved again on 2 February, crossing the Waitotara River by raft and establishing posts at Waitotara, Patea and several other places before arriving at the Waingongoro River, between Hāwera and Manaia, on 31 March, where a large camp and redoubts were built. Troops encountered fire at Hāwera, but his only other major encounter was at Te Ngaio, in open country between Patea and Kakaramea, on 15 March when the troops were ambushed by about 200 Māori, including unarmed women. Cameron claimed 80 Māori losses, the heaviest loss of Hauhau tribes in the West Coast campaign. His force suffered one killed and three wounded in the Te Ngaio attack, which was the last military attempt by Māori to halt Cameron's northward advance.[4] Cameron's own troops were also losing enthusiasm for the campaign, with one 19th-century writer reporting sympathetic Irish soldiers in the 57th Regiment saying, "Begorra, it's a murder to shoot them. Sure, they are our own people, with their potatoes and fish, and children."[21]

Difficulties with landing supplies on the harbourless coast, as well as the recognition that the land route to New Plymouth was both difficult and hostile, convinced Cameron that it would be prudent to abandon his advance and he returned to Patea, leaving several of the redoubts manned by the 57th Regiment.

Cameron had also declined to attack Weraroa pā, claiming he had an insufficient force to besiege the stronghold and keep communications open. He also refused to waste men's lives on the attack of such an apparently strong position. As historian B.J. Dalton points out, cited by Belich, he had already outflanked the pā, neutralising its strategic importance.[22]: 232–234 By July a frustrated Grey decided to act on his own to take Weraroa, which he claimed was the key to the occupation of the West Coast. On 20 July, without Cameron's knowledge, he joined Captain Thomas McDonnell to lead a mix of colonial forces in raids on several Hauhau villages near the pā, taking 60 prisoners. The pā was shelled the next day and Grey captured the pā after learning it had been abandoned,[4] earning public praise after sustained criticism of the pace of Cameron's campaign.

Warre's campaign

[edit]While Cameron made his slow advance northward along the South Taranaki coast, Warre extended his string of redoubts in the north, by April 1865 establishing posts from Pukearuhe, 50 km north of New Plymouth, to Ōpunake, 80 km south of the town. The redoubts brought the length of Taranaki coastline occupied to 130 km, but the forts commanded practically only the country within rifle range of their parapets.[4] Isolated skirmishing between Māori and British forces led to raids by Warre on 13 June to destroy villages inland of Warea, while on 29 July a mix of British troops and Taranaki Mounted Volunteers returned to Warea, burning villages and engaging in several skirmish's with Māori they encountered; a Māori village was attacked and burnt.[4]

Chute's forest campaign

[edit]On 2 September 1865, Grey proclaimed peace to all Māori who had taken part in the West Coast "rebellion", but with little effect. By 20 September there were further deaths following a Māori ambush at Warea and reprisals by the 43rd Regiment and Mounted Corps. Further skirmishing took place near Hāwera and Patea in October and November. Cameron's replacement, Major-General Trevor Chute, arrived in New Plymouth on 20 September to take command of operations just as Premier Frederick Weld's policy of military self-reliance took effect and the withdrawal of British troops from New Zealand began. The 70th and 65th Regiments were the first to leave the country, with Imperial regiments gradually being concentrated at Auckland.[4]

In contrast to Cameron, who preferred to operate on the coast, Chute embarked on a series of aggressive forest operations, following Māori into their strongholds and storming pā.[23] Following orders from Grey to open a campaign against the West Coast tribes, Chute marched from Wanganui on 30 December 1865, with 33 Royal Artillery, 280 of the 14th Regiment, 45 Forest Rangers under Major Gustavus von Tempsky, 300 Wanganui Native Contingent and other Māori with a Transport Corps of 45 men, each driving a two-horse dray. Chute's force burned the village of Okutuku, inland of Waverley on 3 January 1866 and stormed the pā with bayonets the next day, killing six Māori and suffering seven casualties. On 7 January they repeated the strategy at Te Putahi above the Whenuakura River, killing 14 Māori and losing two Imperial soldiers. Chute reported the Hauhau Māori had been driven inland and followed them. On 14 January he launched an attack on the strongly fortified Otapawa pā, about 8 km north of Hāwera. The pā, occupied by Tangahoe, Ngati-Ruanui and Pakakohi tribes, was considered the main stronghold of South Taranaki Hauhaus. Chute claimed 30 Māori were killed, but the deaths came at a high price: 11 of his force were killed and 20 wounded in what was describe as an impetuous frontal attack on a pā he wrongly assumed had been abandoned.[23] The force moved northward, crossing the Waingongoro River and destroying another seven villages.

On 17 January 1866 Chute launched his most ambitious campaign, leading a force of 514, including Forest Rangers and Native Contingent, to New Plymouth along an ancient inland Māori war track to the east of Mt Taranaki. The momentum of the advance quickly ran out as they encountered a combination of heavy undergrowth and torrential rain. Carrying just three days' provisions, the column ran out of food and did not arrive in New Plymouth until 26 January, having been forced to eat a dog and two horses en route.[23] The march was hailed as a triumph, but Belich commented: "Chute narrowly escaped becoming one of the few generals to lose an army without the presence of an enemy to excuse him."[2] Chute marched back to Wanganui via the coast road, having encircled Mt Taranaki. The five-week campaign had resulted in the destruction of seven fortified pā and 21 villages, along with cultivations and food storages, inflicting heavy casualties.[23]

According to historian B.J. Dalton, the aim was no longer to conquer territory, but to inflict the utmost "punishment" on the enemy: "Inevitably there was a great deal of brutality, much burning of undefended villages and indiscriminate looting, in which loyal Maoris often suffered."[22]: 241 The Nelson Examiner reported: "There were no prisoners made in these late engagements as General Chute ... does not care to encumber himself with such costly luxuries," while politician Alfred Saunders agreed there were "avoidable cruelties". After reading Grey's reports expressing his satisfaction with the Chute campaign, Sir Frederic Rogers, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote back: "I doubt whether the natives have ever attempted to devastate our settlements as we are devastating theirs. There is more destruction than fighting."[22]: 240–243 [24]

McDonnell's campaign

[edit]

In early 1866 military settlers began taking possession of land confiscated from Taranaki Māori to create new townships including Kakaramea, Te Pakakohi and Ngarauru. As surveyors moved on to the land, the Government recalled forces from Ōpōtiki on the east coast to form a camp at Patea to provide additional security. The force consisted of the Patea and Wanganui Rangers, Taranaki Military Settlers, Wanganui Yeomanry Cavalry and kupapa Māori and was commanded by Major Thomas McDonnell, an able but ruthless commander.[2]

A series of attacks on small parties and convoys in June prompted retaliatory raids by McDonnell on local villages, including a bayonet raid on the Pokokaikai pā north of Hāwera on 1 August 1866, in which two men and a woman were killed. McDonnell had only days earlier communicated with the pā and extracted a strong signal that they intended remaining peaceful. A commission of inquiry held into the Pokaikai raid concluded the attack had been unnecessary and that McDonnell's action in lulling the Māori into a state of security and then attacking them had been "improper and unjust".[25][26] A convoy was ambushed by Māori on 23 September in retaliation, with one soldier hacked to death with a tomahawk.[25]

In September 1866 the field headquarters of the South Taranaki force was established at a redoubt built at Waihi (Normanby) and further raids were launched from it in September and October against pā and villages in the interior, including Te Pungarehu, on the western side of the Waingongoro River, Keteonetea, Te Popoia and Tirotiromoana. Villages were burned and crops destroyed in the raids and villagers were shot or taken prisoner.[25] At one village where McDonnell carried out a surprise raid, he reported 21 dead "and others could not be counted as they were buried in the burning ruins of the houses". When protests were raised over the brutality of the attacks, Premier Edward Stafford said such a mode of warfare "may not accord with the war regulations, but it is one necessary for and suited to local circumstances".[24]

With local Māori weakened and intimidated, fighting came to an end in November and an uneasy peace prevailed on the west coast until June 1868,[2] with the outbreak of the third Taranaki War, generally known as Titokowaru's War.

21st century postscript

[edit]The outcome of the armed conflict in Taranaki between 1860 and 1869 was a series of enforced confiscations of Taranaki tribal land from Māori blanketed as being in rebellion against the Government.[7] Since 2001, the New Zealand Government has negotiated settlements with four of the eight Taranaki tribes, paying more than $101 million in compensation for the lands, and apologising for the actions of the government of that day.[27]

See also

[edit]- First Taranaki War

- Titokowaru's War

- New Zealand Wars

- New Zealand land confiscations

- Waitara, New Zealand

- Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements

References

[edit]- ^ Belich dismisses as "inappropriate" the description of later conflict as a second Taranaki war. Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f g Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. pp. 204–205. ISBN 014011162X.

- ^ a b c The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal (PDF), 1996, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cowan, James (1922). "5: Cameron's West Coast Campaign". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ Cowan says the first company of New Zealand Forest Rangers was formed soon after a newspaper advertisement was placed in Auckland's Southern Cross newspaper on 31 July 1863. The advertisement said the rangers would emulate the work of the Taranaki Volunteers, formed earlier that year, in "striking terror into the mauauding natives". The 60-strong company was headed by Lieut. William Jackson of Papakura. A second company was formed later in 1863 under Captain Gustavus Von Tempsky. Cowan, James (1922). "29. The Forest Rangers". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 1.

- ^ "Notice. To All Militiamen and Others". The Daily Southern Cross. Vol. 19, no. 1884. 31 July 1863. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f "4", The Taranaki Report - Kaupapa Tuatahi, Waitangi Tribunal, 1996

- ^ Gorst, John Eldon (1864). "9: The Interregnum". The Maori King; or the Story of Our Quarrel with the Natives of New Zealand. London; Cambridge: MacMillan and Co.

- ^ Harrop, A. J. (1937). England and the Maori Wars. Australia: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd. pp. 167–168.

- ^ The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal, chapter 5, 1996

- ^ a b Cowan, James (1922). "1: Pai-Marire". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Prickett, Nigel (2008). "The Military Engagement at Katikara, Taranaki, 4 June 1863". Papahou: Records of the Auckland Museum. 45: 5–41. ISSN 1174-9202. JSTOR 42905898. Wikidata Q58623361.

- ^ a b c d Cowan, James (1922). "25: The Second Taranki Campaign". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 1.

- ^ Stagg, Geoffrey Troughear. "Victoria Cross: Awards to Imperial Servicemen During the 2nd Maori War". Teara 1966 Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "John Down, VC". Birkenhead Returned Services Association.

- ^ "Capture of Kaitake, Ahuahu and Te Tutu. Destruction of Crops; &c". The Taranaki Herald. 26 March 1864.

- ^ a b Wells, Benjamin (1878). "24. The Renewal of Hostilities". The History of Taranaki: a Standard Work on the History of the Province. New Plymouth: Edmondson & Avery.

- ^ a b c d e f Cowan, James (1922). "2: Attack on Sentry Hill Redoubt". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ a b Cowan, James (1922). "3: The Battle of Moutoa". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ Sinclair, Keith (2000). A History of New Zealand. Penguin. ISBN 0140298754.

- ^ Grace, Morgan Stanislaus (1899). A Sketch of the New Zealand War. London: Horace Marshall and Son – via NZETC. As quoted by Cowan, Vol. 2, chapter 5.

- ^ a b c Dalton, B. J. (1967). War and Politics in New Zealand 1855-1870. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- ^ a b c d Cowan, James (1922). "6: Chute's Taranaki Campaign". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ a b Scott, Dick (1975). "1". Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Heinemann.

- ^ a b c Cowan, James (1922). "15: McDonnell's Taranaki Campaign (1866)". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ Belich, in his 1998 television documentary series, The New Zealand Wars, says the condemnation of McDonnell was made by one of the three commissioners. He was outvoted by the other two commissioners and the commission of inquiry exonerated McDonnell.

- ^ New Zealand Ministry of Justice fact sheet, 2007

Further reading

[edit]- Belich, James (1996). Making Peoples. Penguin Press.

- Binney, Judith (1995). Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Maxwell, Peter (2000). Frontier, the Battle for the North Island of New Zealand. Celebrity Books.

- Simpson, Tony (1979). Te Riri Pakeha. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Sinclair, Keith, ed. (1996). The Oxford Illustrated History of New Zealand (2nd ed.). Wellington: Oxford University Press.

- Stowers, Richard (1996). Forest Rangers. Richard Stowers.

- Vaggioli, Dom Felici (2000). History of New Zealand and its Inhabitants. Translated by Crockett, J. Dunedin: University of Otago Press. Original Italian publication, 1896.

- The People of Many Peaks: The Maori Biographies from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Volume 1, 1769-1869. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books; Department of Internal Affairs. 1990.

KSF

KSF