Serbian Party Oathkeepers

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 40 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 40 min

Serbian Party Oathkeepers Српска странка Заветници | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | SSZ |

| President | Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski |

| Founded | 15 February 2012 |

| Registered | 14 August 2019 |

| Split from | Serbian Radical Party |

| Headquarters | Terazije 38, Belgrade |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Colours | Blue |

| National Assembly | 0 / 250 |

| Assembly of Vojvodina | 0 / 120 |

| City Assembly of Belgrade | 1 / 110 |

| Website | |

| zavetnici | |

The Serbian Party Oathkeepers (Serbian: Српска странка Заветници, romanized: Srpska stranka Zavetnici, abbr. SSZ), commonly known as just Oathkeepers, is a far-right political party in Serbia. Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski has been the party's president since 2021.

Initially known as Serbian Council Oathkeepers, SSZ was formed in 2012 with Stefan Stamenkovski as its first president. SSZ began its actions by organising protests against the recognition of Kosovo, the Brussels Agreement, and Belgrade Pride parades. SSZ entered electoral politics in 2013 and it participated in the 2014 parliamentary election in which it did not win any seats. They later organised protests opposed to the commemoration of Srebrenica massacre and NATO; they also organised a rally in support of convicted war criminal Ratko Mladić. SSZ unsuccessfully sought to win seats in the National Assembly of Serbia and City Assembly of Belgrade up to 2022, when SSZ for the first time gained parliamentary representation. It was in the parliamentary opposition to the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). SSZ lost all of its representation in the 2023 elections, in which it contested as part of the National Gathering. After the elections, it aligned itself with SNS, with Đurđević Stamenkovski becoming a government minister in May 2024.

SSZ is an ultranationalist party that pursues sovereignist views towards Kosovo and supports the unification of Serbia and Republika Srpska, an entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is also socially conservative and supports restricting Serbia's immigration system. SSZ supports labelling non-governmental organisations funded from abroad as "foreign agents". An Eurosceptic and anti-NATO party, it is in favour of forging closer relations with Russia and China. It is also opposed to sanctioning Russia in regards to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. SSZ has closely cooperated with United Russia, the ruling party of Russia, and has also received support from the far-right Alternative for Germany.

History

[edit]2012–2014

[edit]

Initially, the organisation was known by names Oathkeepers of Kosovo and Metohija (Zavetnici Kosova i Metohije) and Serbian Council Oathkeepers (Srpski sabor Zavetnici, SSZ).[1][2] SSZ was formed on Presentation of Jesus, 15 February 2012, by former members of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS).[3][4] The association derived its name from Kosovo Myth, a national myth based on legends about the Battle of Kosovo.[3][5] A day after SSZ's formation, Stefan Stamenkovski, its president, gave a speech during a protest that was organised in opposition to the recognition of Kosovo in Prague, Czech Republic, while on 17 February, the organisation was one of the organisers of a protest in Belgrade.[1][2] The protest was organised by SSZ and far-right organisations such as Dveri, Obraz, SNP Naši, and 1389 Movement.[6] Shortly before Hillary Clinton's visit to Belgrade in October 2012, SSZ again organised a protest in opposition to the recognition of Kosovo.[7]

Beginning in April 2013, SSZ organised protests in opposition to the Brussels Agreement, the agreement that normalised relations between Serbia and Kosovo.[8][9] Milica Đurđević, the spokesperson,[10]: 67 one of the co-founders of SSZ and then a student of the University of Belgrade, said in a 2013 interview that SSZ used internet activism to spread their views and claimed that, by the time of the interview, the organisation had several thousand members.[11] SSZ later organised a counter-protest to the Belgrade Pride parade in September 2013.[12][13] Đurđević has said that the pride parades "distracted Serbs from their real social and political problems".[14] During the process of rehabilitation of Draža Mihailović, the leader of Chetniks during the World War II, a group of its members protested in front of the building of the Higher Court in Belgrade in December 2013.[15] In the same month, SSZ contested its first election, the local election in Voždovac, with Dveri.[16]: 6 Đurđević was one of the candidates on the electoral list.[16]: 7 The list did not win any seats in the City Assembly of Voždovac.[17]

SSZ celebrated its two years of existence in the Russian House, Belgrade.[10]: 68 In March 2014 it contested the parliamentary election with Borislav Pelević's Council of Serbian Unity, as part of the Patriotic Front.[3][18][19] Đurđević was the representative of the electoral list.[18] The list did not win any seats in the National Assembly of Serbia.[20] In the same month, SSZ came in support of activist Radomir Počuča, who called for members of the Women in Black organisation to be lynched.[21][22] On Vidovdan (28 June), SSZ members held a public performance in Sarajevo, holding a banner that had "Serbian Princip lives forever" (Srpski Princip zauvek živi) written on it; this caused controversy in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[23] Later in November 2014, SSZ organised a counter-protest to a gathering organised by the Women in Black, who commemorated the end of the Battle of Vukovar.[24][25]

2015–2017

[edit]SSZ organised an exhibition in Belgrade in June 2015 named "British genocidal policy" (Britanska genocidna politika) that showed "photographs of United Kingdom's war crimes from the end of the 19th century to the present day" (fotografije ratnih zločina Velike Britanije od kraja 19. veka do današnjih dana).[26] A month later, it organised a counter-protest to the commemoration of the Srebrenica massacre;[27][28] SSZ repeated this in 2017.[29] SSZ denies the Srebrenica massacre.[30] Together with Obraz, it organised an anti-NATO protest in February 2016 which was participated by several thousand demonstrators.[31][32] A month later it again organised a protest against Serbia's cooperation with the NATO Support and Procurement Agency.[33][34] Đurđević described the cooperation between Serbia and NATO as "disrespectful to the Serbian people".[33]

SSZ contested both the parliamentary election and Vojvodina provincial election in April 2016.[35][36] Božidar Zečević, a playwright, was the representative of the list for the parliamentary election while Đurđević was featured second on its electoral list.[37] SSZ campaigned on forging closer relations with Russia while being opposed to cooperation with NATO and the European Union.[38] During the campaign period, SSZ has received the least attention, according to non-governmental organisation CRTA.[39] It won 0.7 percent of the popular vote and no seats in the National Assembly.[40]

In 2017, members of SSZ interrupted a projection of a documentary film, a festival, and a book promotion.[41][42][43] They deemed them as "harmful to the state" (štetnim za državu) and have called the organisers "traitors" (izdajnici).[41] In July 2017, SSZ organised a rally in support of convicted war criminal Ratko Mladić, claiming that "Mladić liberated Srebrenica".[44] Đurđević married Stamenkovski in September 2017.[45]

2018–2020

[edit]SSZ took part in the Belgrade City Assembly election in March 2018; it began campaigning in late January.[46][47] It campaigned on building a memorial building for Dragutin Gavrilović, giving Mirijevo the status of a municipality, criticising non-governmental organisations, whom they labelled "foreign mercenaries" (strani plaćenici), and arranging Belgrade's river banks and piers.[47][48][49][50] It won 0.65 percent of the popular vote.[51] Following the election, its members unsuccessfully tried to stop the projection of a movie titled Kosovo... Nazdravlje! Gezuar! (Kosovo... Cheers!).[52][53] Later in May 2018, SSZ organised a counter-protest to the Mirëdita, dobar dan! (Good Day!) festival with the SRS.[54] Đurđević Stamenkovski has accused the festival organisers of "treating Kosovo as an independent state" (Kosovo tretira kao nezavisna država).[55]

SSZ again organised a counter-protest during the Mirëdita, dobar dan! festival in 2019 and 2020.[56][57] On 14 August 2019, SSZ registered itself as a political party under the name Serbian Party Oathkeepers.[58][59] N1 news channel reported allegations that members of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) were one of the signatories while SSZ was collecting signatures to become a political party.[60][61][62]: 34 Later in December 2019, it organised a protest in support of the ongoing clerical protests in Montenegro.[63]

Initially, parliamentary elections were to be held in April 2020, however, the election was postponed to June 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[64][65] The Republic Electoral Commission accepted the SSZ electoral list in May 2020.[66][67] Zoran Zečević was featured first on the list, while Đurđević Stamenkovski was featured second.[68] Political scientist Boban Stojanović accused SNS of helping SSZ to collect signatures for its electoral list.[69] SSZ did not cross the 3 percent electoral threshold to gain representation in the National Assembly.[70] After the elections, Đurđević Stamenkovski criticised those who boycotted the election.[71]: 107

2021–2023

[edit]

SSZ signed a cooperation agreement with Vladan Glišić's National Network in February 2021, due to their sharing support for sovereignitism.[72] Beginning in May 2021, inter-party dialogues on electoral conditions without the presence of delegators from the European Union began.[73] SSZ was one of the parties that took part in the dialogues.[74] An agreement between the government and parties that participated in the dialogues was reached in October 2021.[75] In the same month, Đurđević Stamenkovski became the president of SSZ.[‡ 1] While the dialogues were still ongoing, SSZ members interrupted the presentation of Svetislav Basara's book in August 2021, criticising his personal views whom they labelled as "anti-Serbian".[76][77] Later in December 2021, SSZ started campaigning against the proposed changes that were voted in the constitutional referendum in January 2022.[78] A majority of voters that took part in the voting voted in favour of the changes.[79] Following the referendum, SSZ took part in a protest where they demanded the results to be annulled.[80]

SSZ announced its participation in the 2022 general elections in February 2022; Đurđević Stamenkovski was presented as its presidential candidate.[81] It also participated in the Belgrade City Assembly election.[82] During the campaign period, SSZ has stated its opposition to introducing sanctions on Russia while Đurđević Stamenkovski criticised the European Union and NATO.[83][84] In the presidential election, Đurđević Stamenkovski won 4.3 percent of the popular vote while SSZ won 10 seats in the National Assembly.[85][86] Additionally, SSZ gained representation in the City Assembly of Belgrade, with four seats in total.[87] After the elections, SSZ took part in the government negotiations but refused to join the incoming government due to ideological differences, opting to go into the parliamentary opposition.[88]

Two members of the National Assembly and two members of the City Assembly of Belgrade left SSZ in October 2022, criticising Đurđević Stamenkovski and other SSZ members of the National Assembly.[89] SSZ later demanded them to return their mandates.[90] These members joined SNS in February 2023.[91] In March 2023, SSZ was one of the organisers of a protest opposed to the agreement on the path to normalisation between Kosovo and Serbia.[92][93] It has expressed its opposition to the Serbia Against Violence protests, which began after the Belgrade school shooting and Mladenovac and Smederevo shootings in May 2023.[94]

Together with Dveri, SSZ formed a joint councillor group inside the City Assembly of Belgrade in September 2023, while a month later, they formed the National Gathering coalition.[95][96] Miloš Ković, a historian and professor at the Faculty of Philosophy of University of Belgrade, was also one of the initiators; Dveri and SSZ also invited the People's Party (Narodna) and member parties of the National Democratic Alternative to join the coalition.[96] Further talks were held in late October 2023, however, Stefan Stamenkovski, on behalf of SSZ, rejected the proposed document, thus not reaching an agreement on joint participation in the 2023 parliamentary election.[97]

In early November 2023, Dragan Nikolić, one of the vice-presidents of SSZ and its member in the National Assembly, left the party and re-joined SNS.[98] The National Gathering coalition also announced Ratko Ristić as their candidate for the 2023 Belgrade City Assembly election.[99] Their electoral lists for the parliamentary and Belgrade City Assembly election lists were accepted on 5 and 13 November respectively.[100][101] On 27 November, their electoral list for the 2023 Vojvodina provincial election was accepted too.[102] SSZ lost all of its representation in the National Assembly and City Assembly of Belgrade, as the National Gathering coalition failed to cross the threshold.[103][104] The National Gathering coalition was dissolved shortly afterwards the election.[105]

2024–present

[edit]Following the 2023 elections, SSZ participated in talks with SNS about joining the People's Movement for the State.[106] On local level, it also aligned itself with SNS in municipalities such as Prokuplje and Pirot.[107][108] In April 2024, it was announced that SSZ would run on the joint list led by SNS and Socialist Party of Serbia for the 2024 Belgrade City Assembly election.[109] Amidst the campaign, Đurđević Stamenkovski became the minister of family welfare and demography in the government led by SNS in May 2024.[110] The Belgrade City Assembly election resulted in SSZ gaining one seat from the joint list.[111][112]

SSZ again stated its opposition to the Mirëdita, dobar dan! festival in June 2024, with Đurđević Stamenkovski alleging that the festival undermines the constitution of Serbia.[113] The Ministry of Internal Affairs then banned the festival from taking place.[114]

Ideology and platform

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Far-right politics in Serbia |

|---|

|

Đurđević Stamenkovski said in a 2013 interview that SSZ is in favour of strengthening relations with Russia while being opposed to the accession of Serbia to the European Union.[11] Sonja Biserko, the president of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, has described SSZ as pro-fascistic.[10]: 67 Political scientist Věra Stojarová has described SSZ as a radical ethno-nationalist party due to them declaratively rejecting fascism.[115] The late University of Sarajevo professor Samir Beglerović described SSZ as neo-fascist.[116]

On the political spectrum, SSZ is positioned on the far-right.[117] It has been also described as a radical right party,[71]: 108 [115][118] and a proponent of populist and anti-globalist rhetoric.[118][119] The party views itself as patriotic,[120] however observers have described SSZ as ultranationalist.[121][122][123] Đurđević Stamenkovski has rejected that SSZ promotes hate, instead claiming that non-governmental organisations are "anti-Serbian" due to allegedly "ignoring Serbian victims of Balkan atrocities committed during the [Yugoslav Wars]".[121] SSZ supports introducing a law that would label non-governmental organisations funded from abroad as "foreign agents".[121][122] SSZ has spread misinformation in regards to the origin of the COVID-19 virus.[124]

SSZ is a socially conservative,[125] traditionalist,[71]: 108 and religious conservative party.[126] Regarding social issues, Dušan Spasojević, a professor at the Faculty of Political Sciences of University of Belgrade, has placed SSZ on the far-right.[127] SSZ supports family values,[128] and the introduction of a law like the Russian anti-gay law in Serbia.[10]: 70 In a television interview, Đurđević Stamenkovski has once said "What is the plus in the LGBT+, zoophiles and pedophiles maybe? You will also ask for the rights of pedophiles".[129] In 2022, it opposed the manifestation of the EuroPride event in Belgrade.[130] SSZ is not opposed to making abortions illegal and instead wants to "raise awareness among women" to lower the number of unwanted pregnancies.[131] Đurđević Stamenkovski has, however, falsely claimed that 100,000 abortions are performed every year in Serbia.[132][133] According to the statistics of the Institute for Public Health "Dr Milan Jovanović Batut", only 11,000 abortions were performed in 2022.[132]

Regarding immigration, it supports changing the current immigration system.[134] It is supportive of increased transparency in regards to how many people in migrant centers expressed their desire to stay in Serbia and building a barrier, similar to Hungarian border barrier, in case of a heavy migrant crisis.[134] SSZ has described the migrant centre near Horgoš as "one of the most serious risks for citizens of Serbia" (jedan od najozbiljnijih rizika za građane Srbije).[135]

SSZ is a Eurosceptic party that is in favour of suspending the accession of Serbia to the European Union.[61] It is instead in favour of sovereignist "Europe of Nations" (Evropu nacija) policy.[136] SSZ supports Serbia's membership in BRICS as an alternative to the European Union.[137] It is also opposed to NATO and instead wants to pursue closer ties with Russia,[118][125][138] and China.[136] SSZ is supportive of Vladimir Putin.[139] After the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, SSZ has opposed sanctioning Russia.[83][140] After the death of Russian activist Darya Dugina in September 2022, members of SSZ drew a mural of her in Belgrade.[141]

SSZ pursues a sovereignist policy towards Kosovo, opposing its recognition as an independent country.[61][142] SSZ is also opposed to the 2013 Brussels Agreement and is in favour of repealing it and bringing back the Serbian Army to Kosovo.[136] It has supported the initiative to repopulate Kosovo with Serbs with kibbutz-style settlements.[71]: 110 Together with Dveri, Narodna, and New Democratic Party of Serbia, it signed a joint declaration for the "reintegration of Kosovo into the constitutional and legal order of Serbia" (Deklaraiju za reintegraciju KiM u ustavno-pravni poredak Srbije) in October 2022.[143] SSZ supports the unification of Serbia and Republika Srpska and denies that a genocide had been committed on Bosniaks in Srebrenica.[120][144]

Organisation

[edit]SSZ has been led by Đurđević Stamenkovski since 28 October 2021.[58][145][‡ 1] Its headquarters is located at Terazije 38, Stari Grad, Belgrade.[58] SSZ was registered as an association in the Agency of Private Registers in September 2012 with Stefan Stamenkovski as its representative.[146] Since May 2023, the association has been in liquidation.[147]

Within the organisation, Đurđević Stamenkovski also served as the president of the party's parliamentary group in the National Assembly during its time in the National Assembly.[148] Dragan Nikolić and Strahinja Erac formerly served as the vice-presidents of the party.[‡ 2]

In a 2017 interview, Đurđević Stamenkovski said that SSZ had 25,000 members.[149] SSZ has used the White Angel and Miloš Obilić on its emblem, while on its coat of arms it has used a shield that dates from the period of the Nemanjić dynasty.[62]: 48 [150]

International cooperation

[edit]Members of SSZ, including Đurđević Stamenkovski, met with Sergey Lavrov, the minister of foreign affairs of Russia, in 2016.[121] In the same year, SSZ established connection with United Russia, the ruling party of Russia.[151] A year later, its members met with representatives of United Russia in Moscow.[152][153][154] Since then, SSZ has retained close relations with United Russia.[155] In December 2023, the youth representatives of SSZ met with A Just Russia – For Truth youth representatives.[156]

In September 2023, Đurđević Stamenkovski hosted a delegation from S.O.S. Romania, including leader Diana Iovanovici-Șoșoacă, and signed a statement of cooperation between the parties.[157][158][159]

Đurđević Stamenkovski met with Tino Chrupalla, the co-leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party, in November 2023; she described AfD as the "leading sovereignist and state-building option in Germany".[160] AfD expressed its support for the SSZ–Dveri coalition and it is also opposed to the recognition of Kosovo.[160] A month later, SSZ and Dveri organised another gathering featuring far-right parties AfD, Hungarian Our Homeland Movement, and Bulgarian Revival.[161] In April 2024, SSZ signed the Sofia Declaration with Revival, Our Homeland Movement, Slovak Republic, Dutch Forum for Democracy, the Swiss Mass Voll, Alternative for Sweden, the Moldovan Revival Party, and the Agricultural Livestock Party of Greece.[162] Đurđević Stamenkovski participated in AfD's campaign for the 2025 German federal election.[163]

In February 2025, Đurđević Stamenkovski spoke at a rally in support of President of Republika Srpska Milorad Dodik in Banja Luka.[164]

List of presidents

[edit]| # | President | Birth–Death | Term start | Term end | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stefan Stamenkovski | 1982– | 15 February 2012 | 28 October 2021 | ||

| 2 | Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski |

|

1990– | 28 October 2021 | Incumbent | |

Electoral performance

[edit]Parliamentary elections

[edit]| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Coalition | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Stefan Stamenkovski | Did not participate | 0 / 250

|

– | Extra-parliamentary | – | |||

| 2014 | 4,514 | 0.13% | 0 / 250

|

Patriotic Front | Extra-parliamentary | [165] | |||

| 2016 | 27,690 | 0.73% | 0 / 250

|

– | Extra-parliamentary | [166] | |||

| 2020 | 45,950 | 1.43% | 0 / 250

|

– | Extra-parliamentary | [167] | |||

| 2022 | Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski |

141,227 | 3.82% | 10 / 250

|

– | Opposition | [168] | ||

| 2023 | 105,165 | 2.83% | 0 / 250

|

NO | Government[a] | [169] | |||

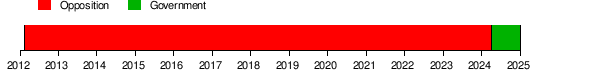

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Presidential elections

[edit]| Year | Candidate | 1st round popular vote | % of popular vote | 2nd round popular vote | % of popular vote | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Did not participate | – | ||||||

| 2017 | Did not participate | – | ||||||

| 2022 | Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski | 5th | 160,553 | 4.33% | — | — | — | [170] |

Belgrade City Assembly elections

[edit]| Year | Leader | Popular vote | % of popular vote | # | # of seats | Seat change | Coalition | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Stefan Stamenkovski | Did not participate | 0 / 110

|

– | Non-parliamentary | – | |||

| 2014 | 996 | 0.12% | 0 / 110

|

Patriotic Front | Non-parliamentary | [171] | |||

| 2018 | 5,301 | 0.65% | 0 / 110

|

– | Non-parliamentary | [172] | |||

| 2022 | Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski |

32,029 | 3.57% | 4 / 110

|

– | Opposition | [173] | ||

| 2023 | 24,213 | 2.63% | 0 / 110

|

NO | Extra-parliamentary | [174] | |||

| 2024 | 366,345 | 52.80% | 1 / 110

|

BS | Government | [112] | |||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Notes

[edit]- ^ The SSZ won no parliamentary representation, but joined the government after the election.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Prag: Održan Marš za Kosovo i Metohiju" [Prague: The March for Kosovo and Metohija was held]. Vesti online (in Serbian). 16 February 2015. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Protesti u Beogradu i Pragu zbog Kosova" [Protests in Belgrade and Prague because of Kosovo]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Srpska stranka Zavetnici" [Serbian Party Oathkeepers]. Istinomer (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Komarčević, Dušan (18 June 2024). "Šta povezuje krajnju desnicu iz Srbije i EU?" [What connects the extreme right from Serbia and the EU?]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Cvetković, Ljudmila (5 June 2020). "Istekao rok: Liste koje su predate za izbore u Srbiji" [The deadline has expired: Lists submitted for the elections in Serbia]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Biserko, Sonja (2012). Populizam: urušavanje demokratskih vrednosti [Populism: the collapse of democratic values] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. p. 38. ISBN 978-86-7208-189-3.

- ^ Milošević, Milan (31 October 2012). "Hilari Klinton po drugi put među Srbima" [Hillary Clinton for the second time among the Serbs]. Vreme (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Postignut dogovor Beograda i Prištine" [Agreement reached between Belgrade and Pristina]. Vreme (in Serbian). 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Ostajemo u Srbiji" [We are staying in Serbia]. Vreme (in Serbian). 10 May 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Biserko, Sonja (2014). Iskonski otpor liberalnim vrednostima [Primordial resistance to liberal values] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

- ^ a b Čabrić, Nemanja (20 May 2013). "Srpska desnica sanja ujedinjenje" [The Serbian right dreams of unification]. Balkan Insight (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "General Kuribak: Danas bezbednosna procena Parade ponosa" [General Kuribak: Pride Parade security will be assessed today]. Politika (in Serbian). 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Glavonjić, Zoran (27 September 2013). "Beogradski Prajd na čekanju" [Belgrade Pride pending]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Čabrić, Nemanja (26 September 2013). "Serbian Rightists Threaten Gay Parade Carnage". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Ponovo zastoj u postupku za rehabilitaciju Draže Mihailovića" [Another stoppage in the procedure for the rehabilitation of Draža Mihailović]. Blic (in Serbian). 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Rešenje o utvrđivanju zbirne izborne liste za izbor odbornika Skupštine gradske opštine Voždovac 15. decembra 2013. godine" [Decision on determining the collective electoral lists for the election of councillors of the Assembly of the City Municipality of Voždovac on 15 December 2013] (PDF). Službeni list Grada Beograda (in Serbian). 4 December 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Zapisnik o raspodeli odborničkih mandata nakon sprovedenih izbora za odbornike Skupštine gradske opštine Voždovac održanih 15. decembra 2013. godine" [Record on the allocation of councillor mandates after the elections for councillors of the Assembly of the City Municipality of Voždovac held on 15 December 2013] (PDF). Službeni list Grada Beograda (in Serbian). 22 December 2013. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Kandidati za poslanike 2014 (4)" [Candidates for deputies in 2014 (4)]. Vreme (in Serbian). 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Objavljena lista pred izbore u Srbiji" [Lists published before the elections in Serbia]. Al Jazeera (in Serbian). 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Izbori 2014" [2014 elections]. Vreme (in Serbian). 25 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Nove prijetnje Ženama u crnom" [New threats to Women in Black]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 6 April 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ Višnjić, Jelena (2016). "Let's begin love anew: right wing on women, women on right wing, case of Serbia". FACTA UNIVERSITATIS - Philosophy, Sociology, Psychology and History. 15 (3): 140.

The latest protest against them was organized by the Zavetnici organization, as a sign of support to the former spokesperson of the Ministry of the Interior Counter-Terrorist Unit, Radomir Poĉuĉa, who was fired after he called for the lynching of Women in Black on his Facebook profile.

- ^ "Princip zauvek živi: Performans na mestu Sarajevskog atentata" [Serbian Princip lives forever: Performance at the Sarajevo assassination site]. Kurir (in Serbian). 12 July 2023. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Ranković, Rade (18 November 2014). "Žene u crnom na godišnjicu stradanja Vukovara" [Women in Black on the anniversary of the suffering in Vukovar]. Voice of America (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Milekić, Sven; Domanović, Milka (19 November 2014). "Seselj Inflames Croatia With Vukovar Jibe". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Veljković, Vladimir (7 July 2015). "Britanci su genocidni a ne Srbi" [The British are genocidal, not the Serbs]. Peščanik (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Nikolić, Ivana (8 July 2015). "Activists Install Srebrenica Memorial in Belgrade". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Ranković, Rade (11 July 2015). "Vučić: Ruka pomirenja ostaje ispružena" [Vučić: The hand of reconciliation remains extended]. Voice of America (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Popović, Veljko (10 July 2017). "Sećanje Žena u crnom na Srebrenicu, kontramiting porodica nestalih Srba" [Remembrance of Women in Black on Srebrenica, counter rally of families of missing Serbs]. Voice of America (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Nešić, Milan (11 July 2015). "Beograd: Sveće za žrtve genocida u Srebrenici" [Belgrade: Candles for the victims of the genocide in Srebrenica]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Todorović, Dragan (25 February 2016). "Zavetnici na zadatku" [Oathkeepers are on a mission]. Istinomer (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Todorović, Dragan (24 February 2016). "Mnogo ljudej" [A lot of people]. Vreme (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b Dragojlo, Saša (4 March 2016). "Anti-NATO Protesters Demand Referendum in Serbia". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Nasilje, bolovi i poverenje" [Violence, pain, and trust]. Vreme (in Serbian). 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Na pokrajinskim izborima 15 partija i koalicija" [In the provincial elections, 15 parties and coalitions]. Radio Television of Vojvodina (in Serbian). 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "RIK proglasio izbornu listu "Za slobodnu Srbiju – Zavetnici"" [RIK announced the electoral list "For A Free Serbia - Oathkeepers"]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Kandidati za poslanike 2016: Lista Za slobodnu Srbiju – ZAVETNICI – Milica Đurđević" [Candidates for deputies in 2016: List For A Free Serbia - OATHKEEPERS - Milica Đurđević]. Vreme (in Serbian). 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Đurđević: Zavetnici jedini nisu izadali svoje principe" [Đurđević: The Oathkeepers were the only ones who did not betray their principles]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Izveštaj posmatračke misije CRTA-građani na straži: vanredni parlamentarni izbori 2016. godine [Report of the observation mission CRTA-citizens on guard: 2016 snap parliamentary elections] (PDF) (in Serbian). CRTA. 2016. p. 40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Izborni rezultat 2016" [2016 election results]. Vreme (in Serbian). 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Učestale akcije desničara, bez reakcije države" [Frequent actions by right-wingers, without a reaction from the state]. Insajder (in Serbian). 25 June 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Radojević, Vesna (2 June 2017). "Zavetnici i Alternativa opet prekinuli tribinu Inicijative mladih za ljudska prava" [Oathkeepers and the Alternative again interrupted the forum of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights]. Istinomer (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Nakratko prekinuta projekcija filma o Kosovu" [The screening of the film about Kosovo was briefly interrupted]. N1 (in Serbian). 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Obradović, Goran (6 July 2017). "Bosnian Serbs to Rally for Ratko Mladic". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Udala se Milica Zavetnica: Stefan pogodio jabuku iz prve, mitropolit Amfilohije pesmom mladencima poželeo sreću!" [Milica Zavetnica got married: Stefan hit the apple in first, Metropolitan Amfilohije wished the newlyweds good luck with a song!]. Kurir (in Serbian). 13 July 2023. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Drčelić, Zora (31 January 2018). "Džet-set liste iz frizerskog salona" [Jet-set lists from the hair salon]. Vreme (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Zavetnici počeli kampanju za beogradske izbore" [Oathkeepers started campaigning for the Belgrade elections]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici: Mirijevo ispunjava sve uslove da postane opština" [Oathkeepers: Mirijevo meets all the conditions to become a municipality]. Radio Television of Serbia (in Serbian). 18 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici 'brane' srpstvo pretnjama" [Oathkeepers are 'defending' Serbia by threatening others]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici: Urediti rečne obale i pristaništa" [Oathkeepers: Arrange river banks and piers]. N1 (in Serbian). 16 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Konačni rezultati: SNS-u 44,99 odsto, lista oko Đilasa 18,93" [Final results: SNS 44.99 percent, list around Đilas 18.93]. N1 (in Serbian). 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Policija izbacila Zavetnike, hteli da prekinu film o Kosovu" [The police kicked out the Oathkeepers, they wanted to stop the film about Kosovo]. N1 (in Serbian). 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Pokušaj 'Zavetnika' da spreče projekciju filma Kosovo.Nazdravlje! Gezuar" [The attempt of the 'Oathkeepers' to prevent the screening of the film Kosovo... Nazdravlje! Gezuar!]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 29 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Festival 'Mirëdita, dobar dan' uz policijsko obezbeđenje" ["Mirëdita, dobar dan" festival with police security]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Policija sprečila grupu huligana da upadne na festival 'Mirëdita, dobar dan!'" [The police prevented a group of hooligans from breaking into the festival 'Mirëdita, dobar dan!']. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 30 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Festival 'Mirëdita, dobar dan!' otvoren uz protest desničara" ['Mirëdita, dobar dan!' festival opened with a right-wing protest]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 30 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Protest zbog festivala "Mirdita, dobar dan"" [Protest due to the 'Mirdita, dobar dan' festival]. Politika (in Serbian). 22 October 2020. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Izvod iz registra političkih stranaka" [Extract from the register of political parties] (PDF). Ministry of State Administration and Local Self-Government (in Serbian). 22 June 2023. p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Đondović, Jelena (17 October 2019). "Radimo isto što i Orban" [We are doing the same as Orban]. Alo! (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Zorić, Jelena (22 May 2019). "Zavetnici skupljaju potpise da postanu stranka, mreže bruje - pomaže im SNS" [Oathkeepers are collecting signatures to become a party, networks are buzzing - SNS is helping them]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Vasić, Marta (27 October 2020). "Geneza i trendovi ekstremne desnice u današnjoj Srbiji" [Genesis and trends of the extreme right in today's Serbia]. Talas (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b Kisić, Izabela (2020). Desni ekstremizam u Srbiji [Right-wing extremism in Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

- ^ "Zavetnici protestovali ispred Ambasade Crne Gore u Beogradu" [Oathkeepers protested in front of the Embassy of Montenegro in Belgrade]. N1 (in Serbian). 28 December 2019. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Vučić: O terminu izbora ću se dogovoriti sa političarima koji su najavili izlazak" [Vučić: On the date of the elections I will talk to the politicians who have announced their departure]. Danas (in Serbian). 12 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Vučić: Izbori 21. juna" [Vučić: Elections on 21 June]. Danas (in Serbian). 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "RIK: Proglašena lista Zavetnici" [RIK: Oathkeepers list proclaimed]. Danas (in Serbian). 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Republic of Serbia: Parliamentary Elections 21 June 2020 (PDF). Warsaw: OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. 2020. p. 11.

- ^ Miladinović, Aleksandar (10 June 2020). "Ko je ko na glasačkom listiću" [Who is who on the ballot]. BBC News (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Stojanović: SNS "overavao" potpise za Levijatan i Zavetnike, Šapić PSG-u i Novoj" [Stojanović: SNS "verified" the signatures for Leviathan and Oathkeepers, Šapić for PSG and Nova]. N1 (in Serbian). 14 August 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Ovo su konačni rezultati izbora u Srbiji!" [These are the final results of the elections in Serbia!]. Mondo (in Serbian). 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Mulhall, Joe; Khan-Ruf, Safya (2021). State of Hate: Far-right extremism in Europe (PDF). London: Hope not Hate.

- ^ "Potpisan protokol o saradnji Srpske stranke Zavetnici i Narodne mreže" [A protocol on the cooperation of the Serbian Party Oathkeepers and the National Network has been signed]. Danas (in Serbian). 17 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Završen prvi sastanak Radne grupe za međustranački dijalog bez posrednika iz EU" [The first meeting of the working group for inter-party dialogues without an EU mediator has ended]. N1 (in Serbian). 18 May 2021. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Inter-Party Dialogue in Serbia: Facilitators to draft a document on electoral conditions by September". European Western Balkans. 12 July 2021. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Popović, Aleksandra (29 October 2021). "Sporazum sa vlašću: Dveri i DJB potpisali, ali nisu sasvim zadovoljni" [Agreement with the authorities: Dveri and DJB signed it but are not completely satisfied]. Danas (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Koprivica, Jelena (7 August 2021). "Haos u Aranđelovcu: Zavetnici upali na promociju knjige i oterali Basaru" [Chaos in Aranđelovac: Oathkeepers broke into a book promotion and chased Basara away]. NOVA portal (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici prekinuli promociju Basarine knjige" [The Oathkeepers stopped the promotion of Basara's book]. N1 (in Serbian). 7 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Valtner, Lidija (2 December 2021). "Desnica se mobiliše za izbore glasanjem protiv ustavnih izmena" [The right is mobilising for elections by voting against constitutional changes]. Danas (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "RIK objavio konačne rezultate referenduma, "za" glasalo manje od 60 odsto" [RIK announced the final results of the referendum, less than 60 percent voted "for"]. N1 (in Serbian). 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Novaković, Ana (17 January 2022). "Protest ispred RIK-a zbog rezultata referenduma, bilo i manjeg koškanja" [Protest in front of the RIK because of the results of the referendum, there was a minor incident]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici samostalno na izbore, Milica Đurđević kandidat za predsednika" [Oathkeepers independently in the elections, Milica Đurđević as candidate for president]. N1 (in Serbian). 6 February 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Beogradski izbori: Lista koalicija i partija sa kandidatima za gradonačelnika" [Belgrade elections: List of coalitions and parties with candidates for mayor]. Vreme (in Serbian). 3 April 2022. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Zavetnici: Srbija da ne uvodi sankcije Rusiji" [Oathkeepers: Serbia not to impose sanctions on Russia]. N1 (in Serbian). 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski: Srbija ne treba da postupa po interesima EU i NATO" [Đurđević Stamenkovski: Serbia should not act according to the interests of the EU and NATO]. Danas (in Serbian). 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Mandat manje za SPS - RIK, Vučić protiv prevremenih izbora na jesen" [A seat less for SPS - RIK, Vučić against early elections in the autumn]. BBC News (in Serbian). 3 April 2022. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "U Srbiji proglašeni konačni rezultati parlamentarnih izbora" [Final results of parliamentary elections announced in Serbia]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 5 July 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Objavljeni konačni rezultati izbora u Beogradu, SNS-u najviše mandata" [The final results of the elections in Belgrade have been published, SNS has the most mandates]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 9 May 2022. Archived from the original on 12 May 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici neće u Vladu, ostaju "državotvorna opozicija"" [The Oathkeepers will not join the government, they will remain the "state-building opposition"]. N1 (in Serbian). 15 July 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Poslanici napustili Zavetnike, ograđuju se od "manipulacija koje narodu servira Đurđević Stamenkovski"" [MPs that left Oathkeepers are distancing themselves from the "manipulations served to the people by Đurđević Stamenkovski"]. NOVA portal (in Serbian). 24 October 2022. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ "Nikolić: Poslanici koji su odlučili da napuste Zavetnike da vrate mandate" [Nikolić: MPs who decided to leave Oathkeepers to return their mandates]. N1 (in Serbian). 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Petoro "Zavetnika" prešlo u SNS, Glišić kaže da im je dosta laži" [Five "Oathkeepers" joined SNS, Glišić says they are fed up with lies]. N1 (in Serbian). 3 February 2023. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Savatović, Mladen (17 March 2023). "Održan skup desnice kod Predsedništva, okupljeni poručili: "Ne kapitulaciji"" [A meeting of the right wing was held at the Presidency, those gathered said: "No to capitulation"]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Right-Wing Serbian Parties Protest Agreement With Kosovo On Anniversary Of NATO Bombing Campaign". Radio Free Europe. 24 March 2023. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Kojić, Nikola (8 May 2023). "Ko od desničara (ne) podržava protest "Srbija protiv nasilja"" [Which of the right-wingers (does not) support the "Serbia Against Violence" protests?]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Savić, Danilo (13 September 2023). "Formirana nova odbornička grupa Zavetnici - Dveri" [A new councillor group has been formed, Oathkeepers–Dveri]. NOVA portal (in Serbian). Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Zavetnici i Dveri formirali "Srpski državotvorni blok", pozvali koaliciju NADA i druge stranke da im se pridruže" [Oathkeepers and Dveri formed the "Serbian State-Building Bloc", they invited the NADA coalition and other parties to join them]. Danas (in Serbian). 4 October 2023. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ Štetin Lakić, Jovana (30 October 2023). "Propali pregovori državotvorne opozicije, Stamenkovski sprečio dogovor" [The negotiations of the state-forming opposition failed, Stamenkovski prevented the agreement]. N1 (in Serbian). Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ ""Vratio se s pozajmice": Poslanik Zavetnika prešao u SNS, obrnuo pun krug" ["He came back from his loan": The Oathkeepers MP switched to the SNS, turning full circle]. N1 (in Serbian). 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ "Koalicija "Nacionalno okupljanje" predala listu za beogradske izbore" [The "National Gathering" coalition submitted its list for the Belgrade elections]. N1 (in Serbian). 12 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "RIK proglasio listu stranke Zavetnici i pokreta Dveri" [RIK proclaimed the electoral list of party Oathkeepers and movement Dveri]. NOVA portal (in Serbian). 5 November 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "GIK Beograd: Proglašene liste "Srbija protiv nasilja", oko Dveri i Zavetnika i lista koalicije Nada" [Belgrade GIK: Proclaimed electoral lists of "Serbia Against Violence", around Dveri and Oathkeepers and the list of coalition NADA]. N1 (in Serbian). 13 November 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "PIK: Proglašene još dve liste za pokrajinske izbore, ukupno 11" [PIK: Two more lists for the provincial elections have been announced, a total of 11]. N1 (in Serbian). 27 November 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "CeSID i IPSOS obradili 99,8 odsto uzorka: SNS-u 128 mandata, SPN-u 65" [CeSID and IPSOS processed 99.8 percent of the sample: SNS 128 mandates, SPN 65]. N1 (in Serbian). 18 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "IPSOS/CeSID: Preliminarni rezultati beogradskih izbora" [IPSOS/CeSID: Preliminary results of the Belgrade elections]. N1 (in Serbian). 17 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ "Prestala da postoji koalicija Nacionalno okupljanje - Dveri i Zavetnici od sada samostalno" [The National Gathering coalition does not exist anymore - Dveri and Oathkeepers to go independently from now on]. N1 (in Serbian). 3 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski: Razgovaramo o mogućem ulasku u Vučićev Pokret za narod i državu" [Đurđević Stamenkovski: We are discussing possible entry into Vučić's Movement for the People and the State]. N1 (in Serbian). 17 February 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Mitić, Ljubiša (13 March 2024). "Zavetnici i zvanično postali deo vladajuće većine u Prokuplju" [Oathkeepers officially became part of the ruling majority in Prokuplje]. Južne vesti (in Serbian). Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ Filipov, Ljubomir (12 February 2024). ""Ujedinimo Pirot" više nije ujedinjen: Zavetnici deo vlasti, POKS nije" ["United Pirot" is no longer united: Oathkeepers now in the government, while POKS is not]. Južne vesti (in Serbian). Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Brnabić o saradnji sa Zavetnicima: Najšira moguća koalicija za Beograd" [Brnabić on cooperation with Oathkeepers: The broadest possible coalition for Belgrade]. N1 (in Serbian). 1 April 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Izglasana nova Vlada Srbije" [New government of Serbia has been elected]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). 2 May 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Koalicija: Aleksandar Vučić - Beograd sutra" [Coalition: Aleksandar Vučić - Belgrade Tomorrow] (PDF). City of Belgrade (in Serbian). May 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Odluka o utvrđivanju preliminarnih rezultata izbora za odbornike Skupštine Grada Beograda, održanih 2. juna 2024. godine" [Decision on determining the preliminary results of the elections for councilors of the City of Belgrade Assembly, held on 2 June 2024] (PDF). City of Belgrade (in Serbian). 3 June 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski o festivalu "Mirdita - dobar dan": Festival treba otkazati, podriva ustavni poredak" [Đurđević Stamenkovski about the "Mirëdita, dobar dan!" festival: The festival should be cancelled, it undermines the constitutional order]. Danas (in Serbian). 15 June 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "MUP zabranio festival "Mirdita, dobar dan", organizatori ukazuju na kršenje Ustava" [The MUP banned the "Mirdita, good day" festival, the organisers point to a violation of the Constitution]. Voice of America (in Serbian). 27 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ a b Stojarová, Věra; Džuverović, Nemanja (2022). Peace and Security in the Western Balkans: A Local Perspective. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-62872-2.

Organisations such as SNP 1389, SNP Naši and Zavetnici declaratively reject fascism and could be labelled as radical ethno-nationalists (radical right)

- ^ Beglerović, Samir (2015). "Svijet bez nasilja i ekstremizma: od izraza prema značenju" [A world without violence and extremism: from expression to meaning]. Znakovi vremena - Časopis za filozofiju, religiju, znanost i društvenu praksu (67): 105.

...rađaju se i raspiruju također antihumani, u ovome slučaju neofašistički pokreti, poput onih koji egzistiraju u Srbiji: "Zavetnici"... [anti-human, in this case neo-fascist movements, such as those that exist in Serbia, are born and fueled: "Oathkeepers"]

- ^ Far-right:

- Biserko, Sonja (2014). Ekstremizam: Kako prepoznati društveno zlo [Extremism: How to recognise social evil] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Helsinški odbor za ljudska prva u Srbiji. p. 230. ISBN 978-86-7208-198-5.

- Imamović, Mirza (4 March 2022). "The Radical Right in the Post-fascist Era". Društvene i humanističke studije. 7 (1(18)): 34. doi:10.51558/2490-3647.2022.7.1.15. ISSN 2490-3647. S2CID 247537622.

Ekstremno desničarske grupacije se u posljednje vrijeme transformišu u političke partije i na tom putu nemaju prepreke. Primjeri za to jesu političke stranke Srpska desnica, osnovana početkom 2018. godine, i Zavetnici. [Far-right groups have recently been transforming themselves into political parties and they have no obstacles on their way. Examples of this are the political parties Serbian Right, founded at the beginning of 2018, and Oathkeepers.]

- Rękawek, Kacper (2022). Foreign Fighters in Ukraine: The Brown–Red Cocktail. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-83041-5.

Serbian far-right groups such as Dveri (Doors) or Srpska stranka Zavetnici (Serbian Party Oathkeepers)

- Dragojlo, Saša (1 March 2022). "Serbian Far-Right Group to Hold Pro-Russia Rally". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Popović, Darko (22 March 2022). "A guide to the 2022 Serbian elections". N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Fridman, Orli (2022). Memory Activism and Digital Practices after Conflict. Amsterdam University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-94-6372-346-6.

- Ristić, Katarina (2018). "The Media Negotiations of War Criminals and Their Memoirs: The Emergence of the "ICTY Celebrity"". International Criminal Justice Review. 28 (4). doi:10.1177/1057567718766218. S2CID 149665526.

...who is supported only by far-right circles, like the Serbian Radical Party (SRS) or "Zavetnici"

- ^ a b c Beckmann-Dierkes, Norbert; Rankić, Slađan (13 May 2022). "Parlamentswahlen in Serbien 2022" [2022 parliamentary elections in Serbia]. Konrad Adenauer Foundation (in German). p. 3. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ Ilić, Aleksa (19 March 2020). "¿No pasarán?" [They shall not pass]. European Policy Centre. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b Zaba, Natalia (17 March 2017). "Rival Activists Embody Serbia's Russia-West Split". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Crosby, Alan (12 March 2018). "Serbian Ultranationalists Making Mark Despite Failure At The Ballot Box". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

The profile of ultranationalist groups such as the Zavetnici

- ^ a b Išpanović, Igor (15 March 2020). "Digitalni šovinizam na Fejsbuku: Dani srpskih nacionalističkih mrmota" [Digital chauvinism on Facebook: Days of Serbian nationalist groundhogs]. Voice (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

Takođe, Damnjan Knežević je i bivši član ultranacionalističke stranke Zavetnici [Also, Damnjan Knežević is a former member of the ultranationalist party Oathkeepers]

- ^ Ultranationalist:

- Beckmann-Dierkes, Norbert; Gogić, Ognjen; Lange, Nils (March 2016). "Serbische Neutralität zwischen NATO und Russland" [Serbian neutrality between NATO and Russia]. Konrad Adenauer Foundation (in German). p. 3. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Mankoff, Jeffrey (7 July 2017). "How to Fix the Western Balkans". Foreign Affairs. ISSN 0015-7120. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

such as the Serbian ultranationalist group Zavetnici

- Knežević, Gordana (14 June 2017). "Lynching Atmosphere Threatens Serbia-Kosovo Dialogue". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Valtner, Lidija (3 November 2020). "Strah od vakcine šansa za populiste" [Vaccine fear is a chance for populists]. Danas (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b Mörner, Ninna (2022). The Many Faces of the Far Right in the Post-Communist Space: A Comparative Study of Far-Right Movements and Identity in the Region. Malmö: Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies. p. 148. ISBN 978-91-85139-13-2.

- ^ Buljubašić, Mirza (2022). Violent Right-Wing Extremism in the Western Balkans: An overview of country-specific challenges for P/CVE. European Commission. p. 13.

- ^ Kojić, Nikola (6 December 2022). "Zašto raste podrška desnici, gde šansu vidi levica i kako je SNS zauzeo centar" [Why is support for the right growing, where does the left see a chance, and how did SNS occupy the centre?]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Popović, Aleksandra (12 April 2022). "Uspon i kontrola desnice u Srbiji - novi politički pol starih ideja" [The rise and control of the right in Serbia - a new political pole of old ideas]. Talas (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Jovanović, Ivana; Anđušić, Anja (2022). Monitoring report on hate speech in Serbia. Media Diversity Institute Western Balkans. p. 12.

- ^ "Koje stranke u Srbiji podržavaju Evroprajd, a koje su protiv" [Which parties in Serbia support Europride, and which are against it]. N1 (in Serbian). 26 August 2022. Archived from the original on 13 January 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Tašković, Marko (2 August 2022). "Kontroverzna inicijativa za zabranu abortusa ujedinila je političke partije u Srbiji: Sve, i vladajuće i opozicione, žestoko se protiv ovoj ideji, osim jedne!" [The controversial initiative to ban abortion has united political parties in Serbia: All, both ruling and opposition, are fiercely against this idea, except for one!]. Blic (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Svake godine se izvrši 100.000 abortusa" [100,000 abortions are performed every year]. Istinomer (in Serbian). 22 November 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Zašto se svako malo manipuliše brojevima abortusa u Srbiji?" [Why are the numbers of abortions in Serbia manipulated every now and then?]. Mašina (in Serbian). 23 November 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b Komarčević, Dušan; Živanović, Maja (13 May 2020). "Migranti i vakcina glavne teme za desnicu u Srbiji" [Migrants and vaccines are the main topics for the right in Serbia]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici: Migrantsko nasilje jedan od najozbiljnijih rizika za gradjane Srbije" [Oathkeepers: Migrant village is one of the most serious risks for the citizens of Serbia]. Danas (in Serbian). 26 November 2022. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Mirilović, Filip (8 April 2022). "Za Putina i pravoslavlje: U šta veruje srpska desnica" [For Putin and Orthodoxy: What the Serbian Right Believes In]. Vreme (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski: Evropska unija ima alternativu, a to je BRIKS" [Đurđević Stamenkovski: The European Union has an alternative, and that is BRICS]. N1 (in Serbian). 14 November 2023. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Vrbaški, Sofija; Magnuson Buur, Stina (2018). Women's rights in Western Balkans. Kvinna till Kvinna Foundation. p. 44.

- ^ Đokić, Danijela (11 August 2014). "Plakati podrške Putinu u Sloveniji" [Posters in support of Putin in Slovenia]. Koreni (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Božić Krainčanić, Svetlana (12 March 2022). "Zašto je u predizbornoj kampanji Srbije 'Ukrajina' nepopularna reč?" [Why is 'Ukraine' an unpopular word in Serbia's pre-election campaign?]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici nacrtali mural posvećen Darji Duginoj u centru Beograda" [Oathkeepers drew a mural dedicated to Darya Dugina in the centre of Belgrade]. N1 (in Serbian). 4 September 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Putin's Asymmetric Assault on Democracy in Russia and Europe: Implications for U.S. National Security (PDF) (Report). United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. 10 January 2018. p. 85. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Pokret za odbranu KiM i pet partija usvojili Deklaraciju za reintegraciju KiM" [The Movement for the Defense of Kosovo and Metohija and five parties adopted the Declaration for Reintegration of Kosovo and Metohija]. Tanjug (in Serbian). 4 October 2022. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Nešić, Milan (11 July 2015). "Beograd: Sveće za žrtve genocida u Srebrenici" [Belgrade: Candles for the victims of the genocide in Srebrenica]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Đurđević: Vlast odbila zahtev da lideri stranaka ne budu nosioci lokalnih lista" [Đurđević: The government rejected the request that party leaders not be holders of local lists]. N1 (in Serbian). 24 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Srpski sabor Zavetnici - U LIKVIDACIJI" [Serbian Council Oathkeepers - IN LIQUIDATION], Agency of Private Registers (in Serbian),

Oblik organizovanja: Udruženje; Datum osnivanja: 21.9.2012; Zastupnici: Stefan Stamenkovski [Form of organisation: Association; Date of establishment: 21.9.2012; Representatives: Stefan Stamenkovski]

- ^ "Rešenje o usvajanju" [Decision on adoption]. Agency of Private Registers (in Serbian). 22 May 2023. p. 1. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

Usvaja se registraciona prijava i registruje se u Registar udruženja, postupak likvidacije nad: "Srpski sabor Zavetnici" [The liquidation procedure registration application is approved and registered in the Register of Associations for Serbian Council of Oathkeepers]

- ^ "Poslanička grupa Srpska stranka Zavetnici" [Parliamentary group Serbian Party Oathkeepers]. National Assembly of Serbia (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ McLaughlin, Daniel (21 November 2017). "Many Serbs in denial over 1990s war crimes ahead of Mladic verdict". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Biserko, Sonja (2014). Extremism: recognizing a social evil (PDF). Belgrade: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. p. 33. ISBN 978-86-7208-200-5.

- ^ "Jedinstvena Rusija i Zavetnici jednoglasni – vojna neutralnost garant bezbednosti" [United Russia and Oathkepers are unanimous - military neutrality is the guarantor of security]. Srbin info (in Serbian). 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Zorić, Ognjen (25 January 2018). "Desno od Vučića i naprednjaka" [To the right of Vučić and the Progressives]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Zavetnici u centrali Putinove stranke; formira se srpski lobi u Rusiji!" [Oathkeepers in the headquarters of Putin's party; a Serbian lobby is being formed in Russia!]. Srbin info (in Serbian). 12 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Komarčević, Dušan (22 March 2022). "Invazija na Ukrajinu desničarski adut pred izbore u Srbiji" [The invasion of Ukraine is a right-wing trump card before the elections in Serbia]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Božić Krainčanić, Svetlana (3 December 2018). "Srpski saveznici Putinove politike" [Serbian allies of Putin's politics]. Radio Free Europe (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "Omladina Zavetnika učestvovala na kongresu omladine Pravedne Rusije: Moskva šalje jaku poruku Srbiji" [The youth of Oathkeepers participated in the congress of the youth of A Just Russia: Moscow sends a strong message to Serbia]. Pravda (in Serbian). 4 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Diana Șoșoacă i-a uimit pe sârbi: a vorbit la Belgrad despre Kosovo, Ucraina și Europa". Stiripesurse.ro. 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Declaraţie comună de presă a preşedinţilor S.O.S. România şi Zavetnici – Serbia". Amos News. 7 October 2023.

- ^ "Senatorul de Iași, Diana Șoșoacă: „Am discutat despre drepturile românilor din Serbia în Parlamentul de la Belgrad"". BZI. 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Đurđević Stamenkovski: Mi želimo Evropu u kojoj će Srbija imati svoje mesto" [Đurđević Stamenkovski: We want a Europe in which Serbia will have its place]. Tanjug (in Serbian). 17 November 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Nacionalno okupljanje i evropske suvernističke stranke za formiranje saveza zbog migrantske krize" [National Gathering and European sovereignist parties to form an alliance due to the migrant crisis]. Novinska agencija Beta (in Serbian). 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Marinova, Tatiana (12 April 2024). "Parties from Nine Countries Sign Joint Declaration at Vazrazhdane-Organized Conference". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski prihvatila poziv da učestvuje na završnoj konvenciji AfD" [Đurđević Stamenkovski accepted the invitation to participate in the final AfD convention]. Tanjug (in Serbian). 17 February 2025. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- ^ "Đurđević Stamenkovski: Dodik čuvar interesa Srpske, volja naroda jača od topuza". Faktor. 25 February 2025.

- ^ Vukmirović, Dragan (2014). Izbori za narodne poslanike Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Elections for deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 9. ISBN 978-86-6161-108-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Kovačević, Miladin (2016). Izbori za narodne poslanike Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Elections for deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 9. ISBN 978-86-6161-154-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Kovačević, Miladin (2020). Izbori za narodne poslanike Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Elections for deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 9. ISBN 978-86-6161-193-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Kovačević, Miladin (2022). Izbori za narodne poslanike Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Elections for deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 7. ISBN 978-86-6161-221-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Kovačević, Miladin (2024). Izbori za narodne poslanike Narodne skupštine Republike Srbije [Elections for deputies of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 9. ISBN 978-86-6161-252-7. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Kovačević, Miladin (2022). Izbori za predsednika Republike Srbije [Elections for the President of the Republic of Serbia] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. p. 7. ISBN 978-86-6161-220-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Izveštaj o ukupnim rezultatima izbora za odbornike Skupštine Grada Beograda" [Report on the overall results of the elections for councillors of the City Assembly of Belgrade] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Gradska izborna komisija. 20 March 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Zapisnik o radu gradske izborne komisije na utvrđivanju rezultata izbora za odbornike Skupštine Grada Beograda" [Report of the work of the city election commission on determining the results of the elections for councillors of the City Assembly of Belgrade] (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Gradska izborna komisija. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Ukupan izveštaj o rezultatima izbora za odbornike Skupštine grade Beograda" [Overall report on the results of the elections for councillors of the City Assembly of Belgrade] (PDF). City of Belgrade (in Serbian). 9 May 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Izveštaj o rezultatima izbora za odbornike Skupštine grade Beograda" [Report on the results of the elections for councillors of the City Assembly of Belgrade] (PDF). City of Belgrade (in Serbian). 2024. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

Primary sources

[edit]In the text these references are preceded by a double dagger (‡):

- ^ a b "Izveštaj nezavisnog revizora i godišnji finansijski izveštaj za 2021. godinu" [Independent auditor's report and annual financial report for 2021] (PDF). Serbian Party Oathkeepers (in Serbian). 14 April 2022. p. 6. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

Datum imenovanja ovlašćenog liza iz člana 31. zakona: 28.10.2021. [Date of appointment of the authorised person from Article 31 of the law: 28.10.2021.]

- ^ "Poslanički klub" [Parliamentary group]. Serbian Party Oathkeepers (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

KSF

KSF