Shopi

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 35 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 35 min

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians Македонци |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

Shopi or Šopi (South Slavic: Шопи) is a regional term, used by a group of people in the Balkans. The areas traditionally inhabited by the Shopi or Šopi is called Shopluk or Šopluk (Шоплук), a mesoregion.[1] Most of the region is located in Western Bulgaria, with smaller parts in Eastern Serbia and Eastern North Macedonia, where the borders of the three countries meet.[2]

The majority of the Shopi (those in Bulgaria, as well in the Bulgarian territories annexed by Serbia in 1919) identify as Bulgarians, those in the pre-1919 territory of Serbia—as Serbs and those in North Macedonia—as ethnic Macedonians.

The boundaries of the Shopluk in Bulgaria are a matter of debate, with the narrowest definition confining them only to the immediate surroundings of the City of Sofia, i.e., the Sofia Valley.[3] The boundaries that are most commonly used overlap with the Bulgarian folklore and ethnographic regions and incorporate Central Western Bulgaria and the Bulgarian-populated areas in Serbia.[4] It is only rarely that the Shopluk is meant to include Northwestern Bulgaria, which is the widest definition (and the one used here).[5]

Name

[edit]According to Institute for Balkan Studies, the Shopluk was the mountainous area on the borders of Serbia, Bulgaria and North Macedonia, of which boundaries are quite vague, in Serbia the term Šop has always denoted highlanders.[6] Shopluk was used by Bulgarians to refer to the borderlands of Bulgaria, the inhabitants were called Shopi.[7] In Bulgaria, the Shopi designation is currently attributed to villagers around Sofia.[8] According to some Shopluk studies dating back to the early 20th century, the name "Shopi" comes from the staff that local people, mostly pastoralists, used as their main tool. Even today in Bulgaria one of the names of a nice wooden stick is "sopa".

Shopluk area

[edit]

- Western Bulgaria (White Shopluk[citation needed])

- Sofia City Province (villages around Sofia, capital of Bulgaria)

- Sofia Province (part of the Small Shopluk)

- Pernik Province (part of the Small Shopluk)

- Kyustendil Province (part of the Small Shopluk)

- occasionally also the western parts of the Blagoevgrad Province as Black Shopluk[citation needed]

- occasionally also the Montana Province

- occasionally also the Vidin Province

- occasionally also the Vratsa Province

- Southeastern Serbia

- Northeastern North Macedonia

- the eastern part of the Northeastern statistical region (the municipalities of Kratovo, Kriva Palanka, Rankovce, Staro Nagoričane[11][9]

- the eastern part of the Eastern statistical region (the municipalities of Berovo, Pehčevo, Delčevo, Makedonska Kamenica, Probištip, Kočani, Vinica)[11][9]

- the Novo Selo Municipality and several highland villages in the Radoviš Municipality[9]

Classification

[edit]

In Bulgaria, the Shopi started gaining visibility as a "group" in the course of the 19th-century waves of migration of poor workers from the Shopluk villages to Sofia.[12]

Bulgarian scholars classify Shopi as a subgroup of the Bulgarian ethnos. As with every ethnographic group, the Bulgarian Academy notes, the Shopi in Bulgaria consider themselves the true and most pure of the Bulgarians, just as the mountaineers around Turnovo claim their land as true Bulgaria from time immemorial, etc.[13]

In the 19th century, the Shopluk area was one of the centres of Bulgarian National Revival. As such, the enture region was made part of the Bulgarian Exarchate upon its establishment in 1870.

In 1875, during the tug-of-war regarding the basis of codificatin of modern Bulgarian, scholar Yosif Kovachev from Štip in Eastern Macedonia proposed that the "Middle Bulgarian" or "Shop dialect" of Kyustendil (in southwestern Bulgaria) and Pijanec (in eastern North Macedonia) be used as a basis for the Bulgarian literary language as a compromise and middle ground between what he himself referred to as the "Northern Bulgarian" or Balkan dialect and the "Southern Bulgarian" or "Macedonian" dialect.[14][15]

According to the Czech Slavist Konstantin Jireček, the Shopi differed a lot from other Bulgarians in language and habits, and were generally regarded as a simple folk. He linked their name and origin to the Thracian tribe of Sapsei.[16]

The American Association for South Slavic Studies has noted that the Shopi are recognized as a distinct sub-group in Bulgaria.[17]

The rural inhabitants near Sofia have popularly been claimed by a number of different authors to be descendants of the Pechenegs.[18][19] The Oxford historian C. A. Macartney studied the Shopi during the 1920s and reported that they were despised by the other inhabitants of Bulgaria for their stupidity and bestiality, and dreaded for their savagery.[20] It is, however, unclear to what extent Macartney's own personal, clearly negative, opinion of the Shopi seeps into this description.

European travellers and ethnographers before 1878

[edit]Stephan Gerlach, a German Protestant theologian travelling back to Central Europe from Constantinople in 1578, described the following Bulgarian towns and villages along the way: "Vedreno" (Vetren); "Ihtimon" (Ihtiman), with mixed population of Turks and Bulgarians; Kazidzham (Kazichene), a Bulgarian village; Sofia, a big city populated by Bulgarians, Greeks, Turks, Jews and Ragusans; Dragomanlii (Dragoman), a small, purely Bulgarian village; Dimitrovgrad, a Bulgarian village; Pirot, mostly Turkish with a minority of Bulgarians; Kuruçeşme (Bela Palanka), a purely Bulgarian village, and, finally, Nissa (Niš), where only few Christians lived, and most of them Serbs—"because this is where Bulgaria ends and Serbia begins".[21]

Another German, Wolf Andreas von Steinach, on his way home from Constantinople in 1583, placed the boundary between Bulgarian and Serbs just west of Niš.[22] The same thing was done in the 1621 journal of yet another traveller, French diplomat Louis Deshayes, Baron de Courmemin, who emphasised that the boundary had been shown to him "by locals".[23]

In the 1590s, Austrian apothecary Hans Seidel wrote about hundreds of chopped-off heads of Bulgarian villagers rolling along the road from Sofia to Niš.[24] In 1664, Englishman John Burberry was baffled by several Bulgarian women in Bela Palanka who threw pieces of butter with salt in front of his company (probably wishing them a safe journey).[25] In 1673, another Austrian traveller, Hans Hönze, described Pirot as the "main city of all of Bulgaria".[26] A decade or so later, Italian military specialist in Austrian service Luigi Ferdinando Marsili described Dragoman, Kalotina and Dimitrovgrad as "Bulgarian villages".[27]

Other travellers who put the ethnographic boundary between Serbs and Bulgarians at Niš include German George Christoff Von Neitzschitz, in 1631;[28] Austrian diplomat Paul Taffner, as part of an embassy to the Sublime Porte, in 1665;[29] German diplomat Gerard Cornelius Von Don Driesch, sent on a mission to Constantinople on the orders of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1723;[30] Armenian geographer Hugas Injejian in 1789, etc. etc.[31] Several maps at the end of the 1700s also place the border between Serbia and Bulgaria around Niš, sometimes west and sometimes east of it.[32][33][34]

When traveling across Bulgaria in 1841, French scholar Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui described the population of the Sanjak of Niš and the Sanjak of Sofia as Bulgarian.[35] The author further designated the population of Niš as Bulgarian and the Niš rebellion (1841) as a Bulgarian uprising.[36] During his travels across European Turkey, French geologist Ami Boué also placed the boundary between Serbs and Bulgarians just north of Niš and identified the towns of Niš, Pirot, Leskovac, Bela Palanka, Dimitrovgrad, Dupnitsa, Blagoevgrad, Radomir, Sofia and Etropole as Bulgarian.[37]

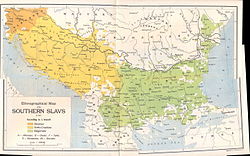

With the launch of the Tanzimat reforms and the tentative opening of the Ottoman Empire to Europe in 1839, the Balkans attracted a large number of European ethnographers, linguists, and geographers, who wanted to study the population of European Turkey. A total of eleven primary ethnic maps of the Balkans were produced between 1842 and 1877: by Slovak philologist Pavel Jozef Šafárik in 1842, Ami Boué in 1847, French ethnographer Guillaume Lejean in 1861, English travel writers Georgina Muir Mackenzie and Paulina Irby in 1867, Russian ethnographer Mikhail Mirkovich in 1867, Czech folklorist Karel Jaromír Erben in 1868, German cartographer August Heinrich Petermann in 1869, renowned German geographer Heinrich Kiepert in 1876, British mapmaker Edward Stanford, French railway engineer Bianconi and Austrian diplomat Karl Sax, all three in 1877.

With the exception of Bianconi and Stanford's maps that portrayed all of Thrace, Macedonia and southern Albania as ethnically Greek and are generally described as having a pro-Greek bias, all other nine maps establish the Serbo-Bulgarian ethnic boundary along the Timok, then just north of Niš and finally along the Šar Mountains, thus defining the entire Shopluk as Bulgarian.[38]

Of interest is also the retroactive study of Bulgaria's population in the 1860s by Russian philologist and dialectologist Afanasiy Selischev, which concluded that the valleys extending from Niš through Pirot and Sofia to the Gate of Trajan near Ihtiman, i.e., the central Shopluk featured the largest concentration of Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire.[39] In recognition of this and as a result of the active participation of the Shopluk in the Bulgarian Church struggle (the first rebellion against a Greek bishop took place in Vratsa in 1828), the entire Shopluk as well as the Pomoravie were included in the territory of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870 and in the Bulgarian autonomous vilayets proposed at the 1876–77 Constantinople Conference.[40]

Modern ethnographic accounts

[edit]According to Serbian historian Miloš Jagodić per Ottoman inventory, made in 1873, the urban population of Niš consisted of 17,107 Christian and 4,291 Muslim males, with total number of 3,500 Serbian houses and 2,000 Muslim houses per Pirot consisted of 29,741 Christian and 5,772 Muslim males, with total number of 3,000 Serbian houses and 400 Muslim houses and Leskovac had 2,500 Serbian and 1,000 Muslim houses.[41] After the Serbian-Ottoman war in 1878 the population of Pirot changed via emigration process of Muslim population, In 1884. Pirot had 77,922 inhabitants, 76,545 being Serbs and 36 Turks. According to Serbian researcher Djordje Stefanović the demographics of Niš underwent change whereby Serbs who formed half the urban population prior to 1878 became 80 percent in 1884.[42].[43] Per Jagodić, in Leskovac of about 5,000 Muslims who had previously lived in the town, 120 were still living there in 1879 and the rest were expelled.[44][45]

The Serbian claim

[edit]Some Serbian sources from the mid 19th century, claimed, the areas southeast of Niš, were mainly Bulgarian populated. The Serbian newspaper Srbske Narodne Novine (Year IV, pp. 138 and 141-43, May 4 and 7, 1841), described the towns of Niš, Leskovac, Pirot, and Vranje as lying in Bulgaria, and styles their inhabitants Bulgarians. On a map made by Dimitrije Davidović called „Territories inhabited by Serbians” from 1828 Macedonia, but also the towns Niš, Leskovac, Vranje, Pirot, etc. were situated outside the boundaries of the Serbian nation. The map of Constantine Desjardins (1853), French professor in Serbia represents the realm of the Serbian language. The map was based on Davidović‘s work placing Serbians into the limited area north of Šar Planina. Per Serbian newspaper, Vidovdan (No. 38, March 29, 1862), the future Bulgarian-Serbian frontier would extend from the Danube in North, along the Timok and South Morava, and then on the ridge of Shar Mountain towards the Black Drin River to the Lake of Ohrid in South.[46]

According to Bulgarian historian Stoyan Raychevski in 1867, Serbia launched a massive campaign to open Serbian schools across the Niš and Pirot regions.[47] Serbia's main competitive advantage was that it offered subsidized teacher salaries, while the Exarchate financed its schools with the membership dues of its parishioners.[48] While some towns like Pirot repeatedly thwarted Serbian attempts to establish schools, due to the proximity of the border and their many refugees in Serbia, both Niš and Leskovac were influenced by Serbian policies within a few years.[49]

Per Raychevski at the Congress of Berlin, the Serbian diplomacy managed to skillfully navigate the conflicting objectives of the Great Powers and by waiving its claims to the Sanjak of Novi Pazar in favour of Austria-Hungary, it managed to gain not only Niš and Leskovac, but also Vranje and even the staunchly Bulgarian Pirot.[50] In this connection, Felix Kanitz noted that back in 1872 the inhabitants of the city would have never imagined that they would be free of the Turks so soon only to end up under foreign rule again.[51] Having their Bulgarian schools closed and the Bulgarian bishop expelled, a large portion of the Bulgarians in Pirot left the town and settled in Sofia, Dimitrovgrad, Vidin, etc.[52][53]

This success encouraged Serbian scholars to further expand their claims beyond the Torlaks and to claim even the Šopi (also known as Šopovi)[54] as a subgroup of the Serbian ethnos, portraying them as closer to the Serbs than to the Bulgarians.[55][56] For example, Serbian ethnographer Jovan Cvijić, presented a study at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where he divided the Shopluk into three groups: Serbs, mixed population, and a group closer to Bulgarians. However, given that his two earlier maps of 1909 and 1913 established the boundary between Bulgarians and Serbs along the state border, his claim has been regarded as little more than a political manoeuvre to justify Serbian territorial claims against Bulgaria.[57]

Then, according to Aleksandar Belić and Tihomir Đorđević, again in 1919, the Shopi were a mixed Serbo-Bulgarian people in Western Bulgaria of Serbian origin.[58] This Serbian ethnographical group, according to them, inhabited a region east of the border as far as the line Bregovo-Kula-Belogradchik-Iskrets, thence towards Radomir and to the east of Kyustendil; to the east of that limit the Serbian population, blended with the Bulgarian element, reached the Iskar banks and the line which linked it to Ihtiman.[58]

Present-day situation

[edit]At present, no Serbian or international linguist supports the claims of Cvijić and Belić, and the border between Serbian and Bulgarian is unanimously defined as the state border between the two countries, except for the districts of Bosilegrad and Dimitrovgrad, which were ceded to Serbia after World War I, where the border follows the old Serbo-Bulgarian border before 1919.[59][60][61]

Similarly, Bulgarian linguistics no longer claims the Serbian Torlakian dialects as Bulgarian. While they were indeed included in the Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects and the adjoining map, both the atlas and the map explicitly state that they present the historical distribution of Bulgarian dialects, i.e., where Bulgarian dialects are or have historically been spoken.[62] Isoglosses are based on 19th and early 20th century records rather than on current data, and Transdanubian settler dialects in Banat and Bessarabia are therefore excluded.

With the establishment of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and the codification of a separate Macedonian language in the 1940s, the bipartite division of the Shopluk has become tripartite. Thus, there are now Shopi who identify as Bulgarians, Serbs and Macedonians and who speak dialects identified as Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian, yet still maintain a regional or ethnographic identity as Shopi. And as modern sociolinguistics places an equally big, if not bigger, emphasis on self-identification and other social factors as on purely linguistic criteria, groups of people speaking the same or similar dialects can still speak different languages—which is the case along much of the shared borders of the three countries.[63]

Most of the area traditionally inhabited by the Shopi is within Bulgaria, while the western borderlines are split between Serbia and the Republic of North Macedonia. The majority of the Shopi (those in Bulgaria, as well in the Bulgarian territories annexed by Serbia in 1919) identify as Bulgarians, those in the pre-1919 territory of Serbia—as Serbs and those in North Macedonia—as ethnic Macedonians.

At the 2011 census in Serbia, they were registered as a separate ethnicity[64] and 142 people declared themselves as belonging to this ethnicity.[65]

Dialects

[edit]Only a minority of the people, whose dialects are referenced here, self-identify as "Shopi". This is particularly true for northwestern Bulgaria, but even in areas close to Sofia, the local population identifies in different ways, e.g., as граовци (graovci) around Pernik and Breznik, знеполци (znepolci) around Tran, торлаци (Torlaks) on the northern and southern side of the Balkan mountain, etc.[11]

Nor are the dialects spoken by this population particularly close to each other: in the Shopluk, there are no fewer than three reflexes of the big yus (ѫ): /ɤ/, /u/ and /a/;[66] three reflexes of Old Bulgarian's syllabic r (ръ~рь): syllabic r, ръ (rɤ) and ър (ɤr);[67] and the whopping five reflexes of Old Bulgarian's syllabic l (лъ~ль): syllabic l, лъ (ɫɤ), ъл (ɤɫ), ъ (/ɤ/) and у (/u/).[68] Even the clearly predominant щ~жд (ʃt~ʒd) reflex of Pra-Slavic *tʲ~*dʲ (as in standard Bulgarian) is challenged by the typically Torlak ч~дж (t͡ʃ~d͡ʒ) along the border with Serbia, by шч~жџ (ʃtʃ~dʒ) in eastern North Macedonia and even by the typically Macedonian ќ~ѓ (c~ɟ) around Kriva Palanka and Kratovo.[69]

The few unifying characterics of the dialects are that they belong to the "et" (western) group of Bulgarian dialects and that they are extremely analytical (i.e., are part of Balkan Slavic). Even though the range presented here does include several dialects which Serbian dialectology refers to as Torlakian and that both terms are often used interchangeably in Serbian, Torlakian and Shopski, in a strictly linguistic sense, refer to entirely different things. The Torlakian dialects, along with the Northwestern Bulgarian dialects and the Northern Macedonian dialects share features of and are transitional between Western and Eastern South Slavic. They also generally shade more and more towards Serbian, Bulgarian and Macedonian the further west, east and south you go.

On the other hand, "Shopski" is just an alternative (and rather incorrect) designation for the Western Bulgarian dialects, and though they are part of the South Slavic dialectal continuum, they are not transitional to any language.[70] Instead, Western Bulgarian dialects are divided into Southwestern, spoken in Central Western and Southwestern Bulgaria, except for the region around Sofia; Northwestern, spoken in Northwestern Bulgaria and around Sofia and Outer Northwestern, spoken along the border with Serbia and by the Bulgarian minority in the Western Outlands in Serbia. It is only the latter group that is transitional to Torlak and therefore Serbian, which is why it is sometimes referred to as "Transitional dialects".

The Torlak dialects spoken by Serbs are also classified by Bulgarian linguists as part of the Transitional Bulgarian dialect, although Serbian linguists deny this. The speech that tends to be closely associated with that term and to match the stereotypical idea of "Shopski" speech are the South-Western Bulgarian dialects which are spoken from Rila mountain and the villages around Sofia to Danube towns such as Vidin.

People from Eastern Bulgaria also refer to those who live in Sofia as Shopi, but as a result of migration from the whole of Bulgaria, Shopski is no longer a majority dialect in Sofia. Instead, most Sofia residents speak the standard literary Bulgarian language with some elements of Shopski, which remains a majority dialect in Sofia's villages and throughout western Bulgaria, for example the big towns and cities of: (Sofia and Pleven- transitional speech with literary Bulgarian language), Pernik, Kyustendil, Vratsa, Vidin, Montana, Dupnitsa, Samokov, Lom, Botevgrad.

The exposition below is based on Stoyko Stoykov's Bulgarian dialectology (2002, first ed. 1962),[70] and the four volumes of the Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects[71][72] although other examples are used. It describes linguistic features and references them, where relevant, with the respective features in standard Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian.

Features of Shopski shared by all or most western Bulgarian dialects

[edit]Phonology

[edit]- Proto-Slavic *tʲ~*dʲ (the main marker of differentiation between the different Slavic languages) has resulted in щ~жд (ʃt~ʒd) (as in Standard Bulgarian) - леща, между (lentils, between), except for the extreme western parts of the region located in Serbia and North Macedonia, where it shades into ч~дж (t͡ʃ~d͡ʒ) and шч~жџ (ʃtʃ~dʒ), which are transitional to the reflexes in standard Serbian/Macedonian.[73]

- The variable known as /ja/ (променливо я), which corresponds to the Old Bulgarian yat vowel and is realised, in the standard language, as /ja/ or /ʲa/ (/a/ with palatalisation of the preceding consonant) in some positions and /e/ in others, is always pronounced /e/ in Shopski. Example: fresh milk in Shopski presno mleko (пресно млеко) compared with standard Bulgarian - prjasno mljako (прясно мляко) [as in Ekavian Serbian and Macedonian]. However, the existence of numerous cases of "a" after hardened "ц" (t͡s) indicates that the yat line in the past has run west of Vratsa, Sofia, Kyustendil and even Štip in North Macedonia.[74]

- The verbal endings for first person singular and third person plural have no palatalisation. Example: to sit in Shopski - seda, sedǎ (седа/седъ) but in standard Bulgarian, sedjǎ (седя)

- Most dialects have little or no reduction of unstressed vowels (as in Serbian), with the exception of the Torlak dialects in Serbian, which, on the other hand, do have reduction (as in Bulgarian)[75]

- All dialects, irrespective of which country they are located in, have dynamic stress and lack either phonetic pitch or length (as in standard Bulgarian and unlike Serbian and Macedonian)

- Historical /l/ in coda position has been preserved in all dialects, as in standard Bulgarian and unlike Serbian, where it is pronounced as o (бил vs. био [was])

- Palatalized /kʲ/ occurs in some cases where it is absent in the standard language. Examples: mother in Shopski is majkja (майкя) and in standard Bulgarian, majka (майка); Bankja (Банкя), the name of a town near Sofia, derived from Ban'-ka (Бань-ка), with a transfer of the palatal sound from /n/ to /k/.

Morphology

[edit]- There are no cases, as in most Bulgarian dialects as well as standard Bulgarian (and unlike Serbian)

- There are definite articles, as in all Bulgarian dialects as well as standard Bulgarian (and unlike Serbian)

- The old Slavic tenses have been kept in full and have been supplemented with additional (inferential) forms, as in all Bulgarian dialects as well as standard Bulgarian (and unlike Serbian)

- The comparative and superlative form of adjectives are expressed analytically, by adding по /po/ and най /nay/, as in all Bulgarian dialects as well as standard Bulgarian (and unlike Serbian)[76]

- There is only one plural form for adjectives, as in all Bulgarian dialects as well as standard Bulgarian (and unlike Serbian)

- The ending for first person plural is always -ме (-me), while in standard Bulgarian some verbs have the ending -м (-m). This feature however also appears in some Southern dialects.[77]

- The definite article for masculine nouns varies. In northwestern Bulgaria, it is ǎ (-ъ). In the Extreme Northwestern Dialects and the Torlak dialects in Serbia, it is -ǎt (-ът), as in Standard Bulgarian. In the Pirdop, Botevgrad and Ihtiman dialect, it is -a (-а). In the rest of the mesoregion, it is -o (-о) as in the Moesian dialects in northeastern Bulgaria.[78]

- The preposition (and prefix) u (у) is used instead of v (в). Example: "in town" is Shopski u grado (у градо) vs. standard Bulgarian v grada (в града), cf. Serbian u gradu.

- 2nd and 3rd personal pronouns across the entire region, including Torlak-speaking areas in Serbia conform to standard Bulgarian/Macedonian forms (e.g. nie (ние) [we], vie (вие) [you]) in contrast with Serbian mi and vi.[79]

- In turn, the 1st person sing. pronoun is ja (я), as in Serbian, instead of az (аз), as in Bulgarian.[80] Similarly, the 3rd person, sing. and pl. pronouns are on (он), ona (она); ono (оно), oni (они), as in Serbian.[81] However, ja is also the pronoun that is used across Southern Bulgaria, all the way to the Black Sea, whereas on, ona, ono, oni were the original pronouns in Old Bulgarian (modern toj, tja, to, te developed in the 11th-12th centuries in some dialects from demonstrative pronouns), so Serbian influence in this particular case is unlikely[82]

- The plural for single-syllable masculine names across the entire region is -ove, i.e., grad > gradove (град > градове) (town > towns) as in standard Bulgarian; in Serbian/Macedonian, the plural suffix is -ovi > gradovi (градови)[83]

- The plural for multiple-syllable masculine names across almost the entirety of the region (except for parts of the Kyustendil dialect) is -e, i.e., učitel > učitele (учител > учителе, teacher > teachers) unlike Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian, which all use the suffix -i.[84] This plural form is a typical Western and Southern Bulgarian feature.

- The plural for feminine nouns ending in -a is -i in most of the region, i.e., žena > ženi (woman > women) as in both standard Bulgarian and standard Macedonian, with the exception of the Outer Northwestern Bulgarian dialects and the adjoining Serbian Torlakian dialects, where it is -e, i.e., žena > žene, as in standard Serbian.[85]

Features characteristic for the South-West Bulgarian dialect group

[edit]Phonology

[edit]- In most (though not all) forms of Shopski, the stressed "ъ" (/ɤ/) sound of standard Bulgarian (which corresponds to Old Bulgarian big yus) or yer) is substituted with /a/ or /o/. Example: Shopski моя/мойо маж ме лаже (moja/mojo maž me laže), че одим навонка (če odim navonka) vs standard Bulgarian моят мъж ме лъже, ще ходя навън/ка) (mojǎt mǎž me lǎže, šte hodja navǎn/ka), (my husband is lying to me, I'll be going out). However, this is not typical either for the Northwestern Bulgarian dialects which have (/ɤ/) for both the big yus or yer, nor for the Bulgarian Extreme Northwestern dialects and the Torlak dialects in Serbia, which have (/ɤ/) for yer.

Morphology

[edit]- The definite article for masculine nouns varies. In the Pirdop, Botevgrad and Ihtiman dialect, it is -a (-а). In the rest of the mesoregion, it is -o (-о) as in northeastern Bulgaria (the Moesian dialects and unlike standard Macedonian, where it is -ot (-oт).[86] Example: otivam u grado (отивам у градо) vs standard Bulgarian otivam v grada (отивам в града), "I am going in town"

- The past passive participle ending varies, depending on participle, for example, for "married" the Northwestern Bulgarian dialects, the Bulgarian Kyustendil dialect and Maleshevo-Pirin dialect and the Timok-Luznica dialect in Serbia use -en/-jen (-ен/-йен), i.e. "женен", as in standard Bulgarian, whereas the Sofia, Tran, Dupnitsa and Elin Pelin dialects use -t (-т), i.e. "женет", as in standard Macedonian.[87] In other cases, -en/-jen (-ен/-йен) is the preferred ending in most of the central and southern parts of the region, as in most southern Bulgarian, i.e. Rup dialects as well as Standard Serbian and Macedonian

- In the past aorist tense and in the past active participle the stress falls always on the ending and not on the stem. Example: Shopski gle'dah (гле'дах), gle'dal (гле'дал) vs standard Bulgarian 'gledah ('гледах), 'gledal ('гледал), "[I] was watching; [he, she, it] watched"

Features characteristic of the Sofia and Elin Pelin dialects

[edit]Morphology

[edit]- In the present tense for the first and second conjugation, the ending for the first person singular is always -м (-m) as in Serbian while in standard Bulgarian some verbs have the ending -а/я (-a/ja). Example: Shopski я седим (ja sedim) vs standard Bulgarian аз седя (az sedja) (I am sitting, we are sitting)

- In the third person singular, present tense, the ending is -ат (-at), as in standard Bulgarian.[88]

- All conjugation forms for the aorist and imperfect follow entirely the standard Bulgarian conjugation pattern, including with ending -ха (-ha) for 3rd person plural for both aorist and imperfect (hu and še in Serbian, respectively)[89]

- Most often the particle for the forming of the future tense is че (če) (Sofia dialect), ке (k'e) or ше (še) (Elin Pelin dialect), instead of standard ще (šte). The form še is used in the more urbanized areas and is rather common in the colloquial speech of Sofia in general. Example: Shopski че одим, ше ода, ке ода/одим (ше) ода (če odim, še oda, k'е oda/odim) vs standard Bulgarian ще ходя (šte hodja) (I will be going)

- Lack of past imperfect active participle, used to form the renarrative mood. In other words, in these dialects there are forms like дал (dal), писал (pisal), мислил (mislil), пил (pil) (past aorist active participles), but no дадял (dadyal), пишел (pishel), мислел (mislel), пиел (piel)

Other features

[edit]The /x/-sound is often omitted. Despite being particularly associated with Shopski, this is actually characteristic of most rural Bulgarian dialects. Example: Shopski леб (leb), одиа (odia) vs standard Bulgarian хляб (hljab), ходиха (hodiha) (bread, they went)

Vocabulary

[edit]There are plenty of typical words for the Shop dialect in particular, as well as for other western dialects in general. Some examples are:

| "Shop" dialects | standard Bulgarian | standard Serbian | standard Macedonian | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| оти?, за какво?, за кво?, що? (oti?, za kakvo?, za kvo?, što?)[citation needed] |

защо?, за какво?, що? (colloq.) (zašto?, za kakvo? što?) |

зашто?, што? (zašto?, što?) |

зошто?, оти? (zošto?, oti?) |

why? |

| сакам (north & centre), искам (south) (sakam, iskam)[90] |

искам, желая (iskam, želaja) |

хоћу, желим, иштем (obsolete) (hoću, želim, ištem) |

сакам (sakam) |

(I) want |

| чиним, правим, работим (činim, pravim, rabotim)[citation needed] |

чиня, правя, работя (činja, pravja, rabotja) |

радим, чиним - do; правим- make (radim, činim pravim) |

работам, чинaм - do, правам - make (rabotam, činam, pravam) |

(I) do/make |

| прашам, питуем (prašam, pituem)[citation needed] |

питам (pitam) |

питам, питуjем (obsolete) (pitam pitujem) |

прашувам (prašuvam) |

(I) ask |

| чувам, пазим (čuvam, pazim)[citation needed] |

пазя (pazja) |

чувам, пазим (čuvam, pazim) |

чувам, пазам (čuvam, pazam) |

(I) keep, bring up, raise (a child) |

| спийем, спим (spijem, spim)[citation needed] |

спя (spja) |

спавам, спим (obsolete) (spavam, spim) |

спиjaм (spijam) |

(I) sleep |

| ядем, ручам (jadem, ručam)[citation needed] |

ям (jam) |

jедем, ручам (jedem, ručam) |

jадам, ручам (jadam, ručam) |

(I) eat |

| варкам, бързам (varkam, bǎrzam)[91] |

бързам (bǎrzam) |

журим (žurim) |

брзам, во брзање сум (brzam, vo brzanje sum) |

(I) search |

| тражим, дирим (tražim, dirim)[citation needed] |

търся, диря (tǎrsja, dirja) |

тражим (tražim) |

барам (baram) |

(I) search |

| барам (baram) |

пипам, докосвам (pipam, dokosvam) |

осећам (osećam) |

чувствувам (čuvstvuvam) |

(I) feel, (I) touch |

| вали, иде, капе (vali, ide, kape)[92] |

вали, капе (vali, kape) |

пада киша (pada kiša) |

врне (vrne) |

(it) is raining / rains |

| окам, викам (okam, vikam)[citation needed] |

викам, крещя (vikam, kreštja) |

вичем, викам (vičem, vikam) |

викам (vikam) |

(I) shout |

| рипам (ripam) |

скачам, рипам (skačam, ripam) |

скачем, рипим (obsolete) (skačеm, ripim) |

скокам, рипам (skokam, ripam) |

(I) jump |

| зборуем, зборувам, приказвам, оратим, говора, вревим, думам (zboruem, zboruvam, prikazvam, oratim, govora, vrevim, dumam) |

говоря, приказвам, думам (obsolete) (govorja, prikazvam, dumam) |

говорим, причам, зборим (archaic) (govorim, pričam, zborim) |

зборувам, говорам, прикажувам, думам, вревам (zboruvam, govoram, prikazhuvam, dumam, vrevam) |

(I) speak |

| кукуруз (north), морус (west), царевица (centre & south), мисирка (extreme south) (kukuruz, morus, carevica, misirka)[93] |

царевица (carevica) |

кукуруз (kukuruz) |

пченка (pčenka) |

maize, corn |

| мачка (mačka) |

котка (kotka) |

мачка (mačka) |

мачка (mačka) |

cat |

| псе, куче (pse, kuče) |

куче, пес, псе (pejorative) (kuče, pes, pse) |

пас, псето, куче (pas, pseto (both pejorative), kuče) |

пес, куче (pes, kuče) |

dog |

| мишка (north & south), поганец (centre) (miška, poganec)([94] |

мишка (miška) |

миш (miš) |

глувче (glufče) |

mouse |

| песница (north & centre), юмрук (south) (pesnica, jumruk)[95] |

юмрук, песница (jumruk, pesnica) |

песница (pesnica) |

тупаница (tupanica) |

fist |

| кошуля, риза (rarely) (košulja, riza) |

риза (riza) |

кошуља (košulja) |

кошула, риза (košula, riza) |

shirt |

Culture

[edit]

The Shopi have a very original and characteristic folklore. The traditional male costume of the Shopi is white, while the female costumes are diverse. White male costumes are spread at the western Shopluk. The hats they wear are also white and tall (called gugla). Traditionally Shopi costume from the Kyustendil region are in black and they are called Chernodreshkovci — Blackcoats. Some Shope women wear a special kind of sukman called a litak, which is black, generally is worn without an apron, and is heavily decorated around the neck and bottom of the skirt in gold, often with great quantities of gold-colored sequins. Embroidery is well developed as an art and is very conservative. Agriculture is the traditional main occupation, with cattle breeding coming second.

The traditional Shop house that has a fireplace in the centre has only survived in some more remote villages, being displaced by the Middle Bulgarian type. The villages in the plains are larger, while those in the higher areas are somewhat straggling and have traditionally been inhabited by single families (zadruga). The unusually large share of placenames ending in -ovci, -enci and -jane evidence for the preservation of the zadruga until even after the 19th century.

Artistic culture

[edit]In terms of music, the Shopi have a complex folklore with the heroic epic and humor playing an important part. The Shopi are also known for playing particularly fast and intense versions of Bulgarian dances. The gadulka; the kaval and the gaida are popular instruments; and two-part singing is common. Minor second intervals are common in Shop music and are not considered dissonant.

Two very popular and well-known fоlklore groups are Poduenski Babi and Bistrishki Babi — the Grandmothers of Poduene and Bistritsa villages.

Cuisine

[edit]A famous Bulgarian dish, popular throughout the Balkans and Central Europe is the Shopska salad, named after the ethnographic group.[96][97][98] The salad was created by state tourist agency "Balkantourist" in 1955,[99][100] as part of an effort to popularize a unique Bulgarian tourist brand.[101] Thus, it has no connection with either the Shopi or the Shopluk.

Social

[edit]

In the 19th century, around Vidin, it was not unusual for a woman in her mid 20s and 30s to have a man of 15–16 years.[7]

The Shopi in literature and anecdotes

[edit]The Shopi — especially those from near Sofia — have the widespread (and arguably unjustified) reputation of stubborn and selfish people[citation needed]. They were considered conservative and resistant to change. There are many proverbs and anecdotes about them, more than about all other regional groups in Bulgaria.

A distinguished writer from the region is Elin Pelin who actually wrote some comic short stories and poems in the dialect, and also portrayed life in the Shopluk in much of his literary work.

Anecdotes and proverbs

[edit]- "There is nothing deeper than the Iskar River, and nothing higher than the Vitosha Mountain." (От Искаро по-длибоко нема, от Витоша по-високо нема!).

- This saying pokes fun at a perceived facet of the Shop's character, namely that he's never traveled far from his home.

- Once a Shop went to the zoo and saw a giraffe. He watched it in amazement and finally said: "There is no such animal!" (Е, те такова животно нема!)

- So even seeing the truth with his own eyes, he refuses to acknowledge it.

- Once a Shop went to the city, saw aromatic soaps on a stand and, thinking that they were something to eat, bought a piece. He began to eat it but soon his mouth was filled with foam. He said: "Foam or not, it cost money, I shall eat it." (Пеняви се, не пеняви, пари съм давал, че го ядем.)

- When money is spent, even unpleasant things should be endured.

- How was the gorge of the Iskǎr River formed? As the story goes, in ancient times the Sofia Valley was a lake, surrounded with mountains. The ancient Shopi were fishermen. One day, while fishing with his boat one of them bent over in order to take his net out of the water. But the boat was floating towards the nearby rocks on the slope of the Balkan Mountains. Consequently, the Shop hit his head on the rocks and the entire mountain split into two. The lake flew out and the gorge was formed.

- There is a saying throughout Bulgaria that the Shopi's heads are wooden (дървена шопска глава, dǎrvena šopska glava), meaning they are too stubborn. In Romania there is such saying about Bulgarians in general.

- Once upon a time three Shopi climbed on top of the Vitosha Mountain. There was a thick fog in the valley so they thought it was cotton. They jumped down and perished.

- This is to show three points: the Shopi are not very smart after all; Vitosha is very high; and, as a serious point, it is common to see Vitosha standing over low clouds shrouding the high plains and valleys of Western Bulgaria; this is a temperature inversion.

- Another example of the Shopi's stubbornness: Once, in the middle of summer, a Shop wore a very thick coat. When asked if it wasn't too hot, he answered: It's not because of the coat but because of the weather.

- The Shopi had a reputation of being good soldiers nevertheless there was a proverb: "A Shop will only fight if he can see the roof of his house from the battlefield", meaning he will only fight if he can see his personal interests in the fight. A proverb that wants to demonstrate the Shopi's selfishness, but may rather point to their conservatism, lack of interest to the outside world.

- Some Shop shepherds are said to have observed over 40 or 50 years from their meadows on the Vitosha mountain how the capital city - Sofia situated few kilometers downhill grew from 80 000 to 300 000 in the 1930s, how new buildings and parks sprang... but never took interest to go and see the city themselves.

- In other parts of Bulgaria all locals from Sofia are called, somewhat scornfully, "Shopi", although the majority of the city's population are not descendants of the real vernacular minority but of migrants from other regions.

- In addition, in other parts of Bulgaria there exists the use of the derisive form "Shopar" for Shop and "Shoparism" for untidy, outdated or primitive circumstances (which show some similarity to the employ of the term "Hillbilly" in the USA). Actually the word "shopar" in Bulgarian means "young boar" and has nothing to do with the Shopi. It is a term for untidiness, since the boar is a close relative to the pig.

- The sayings about the Shopi does not seize in modern day. There are popular sayings from communist period of Bulgaria such as:

- Even if the gasoline price grows to $100 I'll still drive my car. Even if the price drops to a penny, I am not buying it still.

- I will set my house on fire so the fire spread over my neighbor's barn.

- They pretend to pay me decent salary; I pretend that I am working (also very common in the former USSR).

- I take a look behind me – nothing; I take a look around me – nothing; and I am thinking – there is something. (It shows the paranoia of the Shop that the world is out to get him/her)

- A traveler came upon two Shopi sitting in the village square. Since he was traveling to Istanbul he asked one of them for directions in English. The Shopi made a clicking sound with his mouth and shook head, I don't understand. The traveler attempted the same question in French, German, Russian, Spanish and other languages, but had the same result. Aggravated, the traveler started going in one direction that happened to be wrong. The second Shopi, observing this scene, lamented to his buddy “Ah, this guy knows so many languages and you knew none of them.” The first Shopi said “And what good did it do him?”.

Honours

[edit]Shopski Cove in Antarctica is named after the Shop region.[102]

See also

[edit]- Torlakian dialect, a transitional dialect of Serbian, Bulgarian and Macedonian.

References

[edit]- ^ Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Volume 1 (2010), p. 19, LIT Verlag Münster

- ^ Places to exchange cultural patterns, p. 4

- ^ "Още турският султан проклетисвал шопите. Не замръквайте под открито небе, че няма и да осъмнете читави предупреждава Селим Страшни през 1522". 28 May 2023.

- ^ Bulgarian folklore regions

- ^ "Шопи".

- ^ Balcanica, 2006 (37):111-124, The establishment of Serbian local government in the counties of Niš, Vranje, Toplica and Pirot subsequent to the Serbo-Turkish wars of 1876-1878, [1]

- ^ a b Franjo Rački, Josip Torbar, Književnik (1866), p. 13. Brzotiskom Dragutina Albrechta (in Croatian)

- ^ Karen Ann Peters, Macedonian folk song in a Bulgarian urban context: songs and singing in Blagoevgrad, Southwest Bulgaria (2002), "shopluk" Google books link, Madison

- ^ a b c d Namichev 2005.

- ^ a b Bulletin of the Ethnographical Institute, Volume 41, 1992 p. 140

- ^ a b c Hristov, Petko (2019). "Шопи". Bulgarian Ethnography (in Bulgarian).

- ^ Places to exchange cultural patterns, p. 1

- ^ Institut za balkanistika (Bŭlgarska akademii͡a͡ na naukite) (1993). Balkan studies, Volume 29. Édition de lA̕cadémie bulgare des sciences. p. 106.

Ethnography has long established that every ethnographic group, even every single village, considers its dialect, manners and customs "true" and "pure", while those of the neighbours, of the rest — even when they are "our people" — still are neither as "true", nor as "pure". In the Shopi villages you will hear that the Shopi are the true and most pure Bulgarians, while the inhabitants of the mountains around Turnovo will claim that theirs is the land of true Bulgarians from time immemorial, etc.

- ^ Newspaper clipping Retrieved 30 March 2023

- ^ Tchavdar Marinov. In Defense of the Native Tongue: The Standardization of the Macedonian Language and the Bulgarian-Macedonian Linguistic Controversies. in Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume One. doi:10.1163/9789004250765_010 p. 443

- ^ The Encyclopædia Britannica: A-ZYM (20 ed.). Werner. 1903. p. 149.

The Upper Mccsian dialect is also called the Shopsko narechie or dialect of the Shopi. Jireček says that these Shopi differ very much in language, dress, and habits from the other Bulgarians, who regard them as simple folk. Their name he connects with the old Thracian tribe of the Sapsei.

- ^ American Association for South Slavic Studies, American Association for Southeast European Studies, South East European Studies Association (1993). Balkanistica, Volume 8. Slavica Publishers. p. 201.

The loci of this commentary are two well-studied Bulgarian villages, Dragalevtsy and Bistritsa, on the western flank of Mount Vitosha.3 Geographically they are a mere eight kilometers apart. Ethnically their base populations are similar, identified by other Bulgarians as Shopi. Shopi are a recognized and distinct sub-group within the relative homogeneity of Bulgaria at large. Being Shop continues to imply conservatism, despite proximity to Sofia. Our concern is with the ethnography of communication in these two village communities. Both experience considerable influences of urbanization, from students and ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert Lee Wolff (1974). The Balkans in our time. Harvard University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780674060517.

The inhabitants of one group of villages near Sofia, the so-called Shopi, were popularly supposed to be descendants of the Pechenegs.

- ^ Edmund O. Stillman (1967). The Balkans. Time Inc. p. 13.

internally by distinctions of dialect and religion, so that the Orthodox Shopi, peasants dwelling in the hills surrounding Bulgaria's capital of Sofia, are alleged to be descendants of the Pecheneg Turks who invaded the Balkans in the 10th ...

- ^ Marshall Lang, David (1976). The Bulgarians. From Pagan Times to the Ottoman Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 41. ISBN 0891585303.

The Pechenegs still survive in Bulgaria, in the plain of Sofia, and are known as 'Sops'. The Oxford historian C. A. Macartney studied these 'Sops' in the 1920s, and reported that they were despised by the other inhabitants of Bulgaria for their stupidity and bestiality, and dreaded for their savagery. They are a singularly repellent race, short-legged, yellow-skinned, with slanting eyes and projecting cheek-bones. Their villages are generally filthy, but the women's costumes show a barbaric profusion of gold lace.

- ^ Gerlach, Stephan (1976). Дневник на едно пътуване до Османската порта в Цариград [Diary of a Trip to the Ottoman Gate]. Sofia. pp. 261–269.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Чужди Пътеписи За Балканите, Том 3 - Немски и австрийски пътеписи за Балканите ХV-ХVІ В. [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 3: German and Austrian Travelogues, 1400–1600]. Наука и изкуство. 1979. p. 431.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите —Френски Пътеписи за Балканите 15-18 в. [Foreign Travel Notes on the Balkans: French Travel Notes on the Balkans]. Sofia: Наука и изкуство. 1975. pp. 39, 199.

- ^ Seide, Friedrich (1711). Denkwürdige Gesandtschaft an die Ottomanische Pforte, Welche auf Rudolphi, II. Befehl Herr Friedrich von Kreckwitz verrichtet [A Memorable Embassy to the Sublime Porte, carried out by Mr. Friedrich von Kreckwitz on the orders of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor]. Görlitz. pp. 84–85.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите. Том 7: Английски пътеписи за Балканите (края на ХVІ в. - 30-те години на ХІХ в.) [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 7: English Travelogues (from the Late 1500s to the 1930s)]. Наука и изкуство. 1987. p. 150.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите: Немски и австрийски пътеписи за Балканите XVII-средата на XVIII в. [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 3: German and Austrian Travelogues, 1600–1750]. Sofia: Наука и изкуство. 1989. p. 159.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите: Немски и австрийски пътеписи за Балканите XVII-средата на XVIII в. [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 3: German and Austrian Travelogues, 1600–1750]. Vol. 6. Sofia: Наука и изкуство. 1989. p. 170.

- ^ Christoff Von Neitzschitz, George (1674). Sieben-jährige und gefährliche neu-verbesserte Europae, Asiat und Afrikanische welt beschreibung [Seven Years of Perilous Travel across Europe, Asia and Africa, a New Description of the World]. Nuremberg. p. 73.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите: Немски и австрийски пътеписи за Балканите XVII-средата на XVIII в. [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 3: German and Austrian Travelogues, 1600–1750]. Sofia: Наука и изкуство. 1989. p. 103.

- ^ Driesch, Gerard Cornelius Von Don (1723). Historische Nachricht Von Der Rom, Kayserl, Gross-Botschaft Nach Constaninopel [Historical Message from the Holy Roman Imperial Embassy to Constantinople]. Nuremberg. p. 79.

- ^ Чужди пътеписи за Балканите. Том 5: Арменски пътеписи за Балканите XVII-XIX в. [Foreign Travelogues on the Balkans, Volume 5: Armenian Travelogues, 1600s–1800s]. Sofia: Наука и изкуство. 1984. p. 115.

- ^ Robert de Vaugondy, Gilles; Robert de Vaugondy, Didier (1757). L'Europe divisee en ses principaux Etats [Europe Divided into its Main Constituent States] (Map). 1:9,500,000. Paris: Les Auteurs.

- ^ Kininger, Vinzenz Georg (1795). XXII. Karte von dem Oschmanischen Reiche in Europa [XXII. Map of the Ottoman Empire in Europe] (Map). 1:3,200,000. Vienna.

- ^ Arrowsmith, Aaron (1798). 1798 Arrowsmith Wall Map of Europe (Map). 1:3,200,000. London.

- ^ Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui, „Voyage en Bulgarie pendant l'année 1841“ (Жером-Адолф Бланки. Пътуване из България през 1841 година. Прев. от френски Ел. Райчева, предг. Ив. Илчев. София: Колибри, 2005, 219 с. ISBN 978-954-529-367-2.)

- ^ "Рая Заимова - Пътуване из България".

- ^ Boué, Ami (1854). Recueil d'Itinéraires Dans La Turquie d'Europe, Vol. 1: Détails Géographiques, Topographiques Et Statistiques Sur Cet Empire [Collection of Itineraries in European Turkey, Vol. 1: Geographic, Topographical and Statistical Details of the Empire]. Vienna. pp. 60–62, 76–92, 220–242.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wilkinson 1951, pp. 34, 36, 44, 50, 53, 54, 55, 66, 70, 71, 75.

- ^ Selischev, Afanasiy (1930). Описание Болгарии в 60-х годах прошлого века [A Description of Bulgaria in the 1860s] (in Russian). Sofia. p. 184.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Other of the evidences, again both foreign and native, follow from 1870 on after the creation of the Bulgarian Exarchate; after the decisions of an European conference in Constantinople (Dec. 1876 — Jan. 1877) for creating two autonomous Bulgarian provinces from the line Timok—Nish—Gnilane—Debar—Kostur, toward the east to the Black sea below Lozengrad; For more see: Johann Georg von Hahn, Bulgarians in Southwest Morava, reissued by Aleksandar Teodorov-Balan (1917) Al. Paskaleff & Co. publishers, Sofia, pp. 26-27.

- ^ Jagodić, Miloš (1998-12-01). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires. 2 (2). doi:10.4000/balkanologie.265. ISSN 1279-7952. S2CID 262022722.

- ^ Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 465–492. doi:10.1177/0265691405054219. hdl:2440/124622. S2CID 144497487. "Prior to 1878, the Serbs comprised not more than one half of the population of Nis, the largest city in the region; by 1884 the Serbian share rose to 80 per cent."

- ^ Hoare, M.A. (2024). Serbia: A Modern History. Hurst Publishers. p. 224.

- ^ Hahn, J. G. von (2015). Rober Elsie (ed.). The discovery of Albania : travel writing and anthropology in the nineteenth-century Balkans. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350154681.

- ^ Jagodić, Miloš (1998-12-01). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires. 2 (2). doi:10.4000/balkanologie.265. ISSN 1279-7952. S2CID 262022722.

- ^ Ethnic Mapping on the Balkans (1840–1925): a Brief Comparative Summary of Concepts and Methods of Visualization, Demeter, Gábor and al. (2015) In: (Re)Discovering the Sources of Bulgarian and Hungarian History. Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia; Budapest, p. 85.

- ^ Raychevski 2004, pp. 144.

- ^ Raychevski 2004, pp. 151.

- ^ Raychevski 2004, pp. 149.

- ^ Raychevski 2004, pp. 170.

- ^ Felix Kanitz, (Das Konigreich Serbien und das Serbenvolk von der Romerzeit bis dur Gegenwart, 1904, in two volumes) # "In this time (1872) they (the inhabitants of Pirot) did not presume that six years later the often damn Turkish rule in their town will be finished, and at least they did not presume that they will be include in Serbia, because they always feel that they are Bulgarians. ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, p. 215)...And today (in the end of 19th century) among the older generation there are many fondness to Bulgarians, that it led him to collision with Serbian government. Some hesitation can be noticed among the youngs..." ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, c. 218; Serbia - its land and inhabitants, Belgrade 1986, p. 218)

- ^ История на България, том седми - Възстановяване и утвърждаване на Българската държава. Национално-освободителни борби /1878-1903/, София, 1991, с. 421-423.

- ^ Българите от Западните покрайнини (1878-1975), Главно управление на архивите, Архивите говорят, т. 35, София 2005, с. 62-64 - А list of immigrants from Pirot in Bulgaria containing 160 names of heads of families.

- ^ Hrvatsko filološko društvo, Filologija, Volumes 1-3 (1957) p. 244, Jugoslavenska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti (in Serbo-Croatian)

- ^ Srpski etnos i velikosrpstvo, pp. 261-262 Jovan Cvijic:Selected statements]

- ^ Cartography in Central and Eastern Europe: Selected Papers of the 1st ICA Symposium on Cartography for Central and Eastern Europe; Georg Gartner, Felix Ortag; 2010; p.338

- ^ Wilkinson 1951, pp. 202 [Cvijić never adequately explained these modificiations. It would seem that in 1913 he had regarded the Bulgarian boundary as inviolable, but by 1918 explansion of Serbia at the cost of Bulgaria had, in estimation, become feasible. Cvijić himself had always been an advocate of ethno-political boundaries, so he appears to have modified his ethnic dispositions, in an endeavour to prepare the way for Serbian claims on Bulgaria. By such a manoeuvre, the Serbian demands for a strategic Serbo-Bulgarian boundary and, in particular, for the incorporation of the Strumica salient within Serbia, were given support].

- ^ a b Crawfurd Price (1919). Eastern Europe ...: a monthly survey of the affairs of central, eastern and south-eastern Europe, Volume 2. Rolls House Pub. Co.

By A. Belitch and T. Georgevitch To the east of the Serbo-Bulgarian frontier, in Western Bulgaria, extends a zone still peopled to-day by a population of Serb origin, presenting a mixed Serbo-Bulgar type, and known under the name of " Chopi " (Shopi). The Serbian ethnographical element left in Bulgaria by the political frontier established at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, maintains itself in its fundamental characteristics, as far as the line joining up Bregovo, Koula, Belogratchik, and Iskretz, and proceeding thence towards Radomir and to the east of Kustendil; to the east of that limit the Serb population, blended with the Bulgar element, reaches the banks of the Isker and the line which links it to Ihtiman.

- ^ Crystal, David (1998) [1987]. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Matasović, Ranko (2008). Poredbenopovijesna gramatika hrvatskoga jezika. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. ISBN 978-953-150-840-7.

- ^ Стойков, Стойко: Българска диалектология, Акад. изд. "Проф. Марин Дринов", 2006, pp. 76-77 [2]

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2016, pp. 11.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-230-29473-8.

Until 1990, the Moldovan language was written in Cyrillic. After adopting the Latin alphabet, Moldovans have virtually the same language as the Romanians. For political reasons, the Moldovan Constitution recognizes Moldovan as the national language of Moldova. This political act alone makes the Moldovan language separate from the Romanian (King 1999). Low German (Plattdeutsch), spoken in northern Germany, is incomprehensible to the speakers of Allemanian German (Allemanisch), which is used in western Austria and southwestern Bavaria. But both are considered to be dialects of the same German language. Low German is virtually identical with Dutch, but the different national identities of the speakers keep them either from proclaiming Low German a dialect of Dutch, or Dutch a dialect of German, or from creating a common Dutch-Low German language.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia, ETHNICITY Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2012. p. 12.

- ^ "Ethnic communities with less than 2000 members and dually declared" (PDF). Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, pp. 199 [3].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, pp. 205–210 [4].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, pp. 208 [5].

- ^ a b Стойков, С. (2002) Българска диалектология, 4-то издание. стр. 143, 186. Also available online

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2016.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 217 [6].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, pp. 95 [7].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2001, pp. 140 [8].

- ^ "Bulgarian Grammar - Comparatives and Superlatives". polyglotclub.com. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ "St. Stojkov - Bylgarska dialektologija - 2 B 4".

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2016, p. 56 [9].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 98 [10].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2016, pp. 85 [11].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 88, 92, 97, 105 [12].

- ^ "Modern Paleoslavistics and Medievalistics, Online Dictionary and Grammar of Old Bulgarian". Cyrillomethodiana. Sofia University St. Clement of Ohrid. 2011–2013.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 32 [13].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 38 [14].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects 2016, pp. 45 [15].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 57 [16].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 161 [17].

- ^ "Електронна библиотека Българско езикознание". ibl.bas.bg. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 152, 155 [18].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 480 [19].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), p. 484.

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2016), pp. 487 [20].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 424 [21].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 436 [22].

- ^ Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects (2001), pp. 468 [23].

- ^ Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity Diversity And Dialogue, Stephen Mennell, Darra J. Goldstein, Kathrin Merkle, Fabio Parasecoli, Council of Europe, 2005, ISBN 9287157448, p. 101.

- ^ Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia, Ken Albala, ABC-CLIO, 2011, ISBN 0313376263, p. 67.

- ^ Mangia Bene! New American Family Cookbooks, Kate DeVivo, Capital Books, 2002, ISBN 1892123851, p. 170.

- ^ That Salad was created by professional chefs from "Balkanturist" in 1956 at the restaurant "Chernomorets" in the then resort "Druzhba", now "Saint Konstantin and Elena" near Varna, Bulgaria. For the first time, the salad recipe appeared in 1956 in a "Book of the hostess" of P. Cholcheva and Al.Ruseva and it contained all the components of today Shopska except the cheese. In the following years, there were undergoing series of modifications to the recipe - in 1970 in the book "Recipe for cooking and confectionery" were given four options for Shopska salad - with onion and cheese; without onion and cheese; with roasted peppers and cheese; not sweet, but with chili pepper and cheese. In the early 1970s, roasted peppers and grated cheese were imposed as a mandatory component. Initially, the salad was served only in restaurants of "Balkanturist" and later it became popular in the home kitchens in the country. It became a national culinary symbol in Bulgaria during the 1970s and 1980s. For more see: Albena Shkodrova, Socialist gourmet, Janet 45, Sofia, 2014, ISBN 9786191860906, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Дечев, Стефан. Българска, но не точно шопска. За един от кулинарните символи, Български фолклор, год. ХХХVІ, 2010, кн. 1, с. 130 – 131, 133, 136.

- ^ Raymond Detrez, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, 3rd ed, 2015, ISBN 978-1-4422-4179-4, p. 451

- ^ Shopski Cove. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer.

Sources

[edit]- Ethnologia Balkanica (2005), Vol. 9; Places to exchange cultural patterns by Petko Hristov, pp. 81-90, Journal for Southeast European Anthropology, Sofia

- Stanko Žuljić, Srpski etnos i velikosrpstvo (1997), Google Books link

- Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. I–III. Фонетика, Акцентология, Лексика [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects. Generalising volume. Vol. I – III. Phonetics. Accentuation. Lexicology] (in Bulgarian). София: Книгоиздателска къща „Труд“ / Trud publishing house. 2001. ISBN 954-90344-1-0. OCLC 48368312.

- Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. IV. Морфология. [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects. Generalising volume. Vol. IV. Morphology] (in Bulgarian). София: BAS Academic Press Marin Drinov. 2016. ISBN 978-954-322-857-7.

- Namichev, Petar (2005). "Народното градителство на шопската етничка заедница во Источна Македонија" [The National Building of the Shop Ethnic Community in Eastern Macedonia]. Skopje. ISSN 1409-6404.

- Raychevski, Stoyan (2004). Нишавските българи [The Bulgarians from the Valley of Nishava]. Sofia: Balkani. ISBN 954-8353-79-2.

- Wilkinson, H.R. (1951). Maps and Politics; a Review of the Ethnographic Cartography of Macedonia (PDF). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780853230724.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

KSF

KSF