Slovak phonology

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Slovak language.

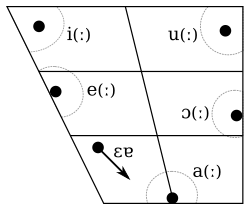

Vowels

[edit]

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː |

| Mid | e | (eː) | ɔ | (ɔː) |

| Open | (æ) | a | aː | |

| Diphthongs | (ɪu) ɪe ɪɐ ʊɔ | |||

- Vowel length is phonemic in standard Slovak. Both short and long vowels have the same quality.[1] However, in native words, it is contrastive mostly in the case of the close /i, iː, u, uː/ and the open back /a, aː/ (but not the open front /æ/, which occurs only as short). Outside of adjective endings, the front long mid vowel /eː/ appears in loanwords along with one native word (dcéra), whereas the back long mid vowel /ɔː/ appears only in loanwords.

- Eastern dialects lack the short–long opposition entirely.[2][3] In Western dialects, vowels that are short due to the rhythmical rule are often realized as long, thus violating the rule.[4]

- The falling diphthongs /ɪe/, /ɪɐ/ as well as /ɪu/ mostly replace /eː/, /aː/ and /uː/ after soft consonants, though there are exceptions such as jún /juːn/ 'June'. /aː/ can also occur after /j/ in some cases. Furthermore, at least /ɪe/ and /ɪɐ/ can also occur after hard consonants, as in kvietok /ˈkvɪetɔk/ 'little flower' and piatok /ˈpɪɐtɔk/ 'Friday', though it is unclear whether there are any minimal pairs that distinguish /ɪe/ from /eː/ as well as /ɪɐ/ from /aː/ purely by vowel quality. /ɪu/ occurs only in a few morphologically conditioned environments.[5][4]

- The front rounded vowels /y, yː, œ, œː/ occur only in loanwords.[3][6] Just as other mid vowels, /œ, œː/ are phonetically true-mid [œ̝, œ̝ː].[7] The occurrence of these vowels has been reported only by Kráľ (1988), who states that the front rounded vowels appear only in the high register and medium register. However, in the medium register, /y, yː/ and /œ, œː/ are often either too back, which results in realizations that are phonetically too close to, respectively, /u, uː/ and /ɔ, ɔː/, or too weakly rounded, yielding vowels that are phonetically too close to, respectively, /i, iː/ and /e, eː/.[8]

- /æ/ is phonetically a diphthong [ɛɐ]. It is shorter than other diphthongs; in fact, it has the length typical of short monophthongs. It occurs only after /m, p, b, v/.[9][3][10] There is not a full agreement about its status in the standard language:

- Kráľ (1988) states that the correct pronunciation of /æ/ is an important part of the high register, but in medium and low registers, /æ/ is monophthongized to /e/, or, in some cases, to /a/.[10]

- Short (2002) states that only about 5% of speakers have /æ/ as a distinct phoneme, and that even when it is used in formal contexts, it is most often a dialect feature.[11]

- Hanulíková & Hamann (2010) state that the use of /æ/ is becoming rare, and that it often merges with /e/.[3]

Phonetic realization

[edit]- The close /i, iː, u, uː/ are typically more open [i̞, i̞ː, u̞, u̞ː] than the corresponding cardinal vowels. The quality of the close front vowels is akin to that of the monophthongal allophone of RP English /iː/.[12]

- The mid front /e, eː/ are typically higher than in Czech, and they are closer to cardinal [e] (but still not as close, so [e̞]) than [ɛ]. In turn, the mid back /ɔ, ɔː/ are typically more open than their front counterparts, which means that their quality is close to cardinal [ɔ].[1]

- The open front vowel /æ/ is a phonetic diphthong, transcribed [ɛɐ] in this article. A narrower transcription is [ɛ̠ɐ̟], as it is a diphthong that starts below and more central than /e/ and glides to the frontest and closest allophone of /a/.[9]

- The open back vowels /a, aː/ are phonetically central [ä, äː].[13]

- Under Hungarian influence, some speakers realize /ɔː/ as close-mid [oː] and /a/ as open back rounded [ɒ]. The close-mid realization of /ɔː/ occurs also in southern dialects spoken near the river Ipeľ.[14]

- /ɪu, ɪe, ɪɐ, ʊɔ/ are all rising, i.e. their second elements have more prominence.[4][15]

- The phonetic quality of Slovak diphthongs is as follows:

- /ɪe/ and /ɪu/ have the same starting point, the same as the short /i/. The former glides to the short /e/ ([ɪ̟e̞]), whereas the latter glides to the position more front than /u/ ([ɪ̟ʊ]), so that /ɪu/ ends more front than the starting point of /ʊɔ/.[16]

- /ɪɐ/ is typically a glide from the position between /i/ and /e/ to the ending point of /æ/ ([e̝ɐ̟]).[17]

- /ʊɔ/ is typically a glide from /u/ to the closest allophone of /ɔ/ ([ʊ̠o̞]).[16]

- There are many more phonetic diphthongs, such as [aw] in Miroslav [ˈmirɔslaw] and [ɔw] in Prešov [ˈpreʂɔw]. Phonemically, these are interpreted as sequences of /v/ preceded by a vowel. This [w] is phonetically [ȗ̞] and it is very similar to the first element of /ʊɔ/.[18][19]

Transcriptions

[edit]Sources differ in the way they transcribe Slovak. The differences are listed below.

| This article | Short 2002[11] | Pavlík 2004[20] | Krech et al 2009[21] | Hanulíková & Hamann 2010[4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | i | i̞ | i | i̞ |

| iː | iː | i̞ː | iː | i̞ː |

| u | u | u̞ | u | u̞ |

| uː | uː | u̞ː | uː | u̞ː |

| e | e | e̞ | ɛ | ɛ |

| eː | eː | e̞ː | ɛː | ɛː |

| ɔ | o | ɔ̝ | ɔ | ɔ |

| ɔː | oː | ɔ̝ː | ɔː | ɔː |

| æ | æ | ɛ̠̆ɐ̟̆ | æ | æ |

| a | a | ɐ̞ | a | a |

| aː | aː | ɐ̞ː | aː | aː |

| ɪu | iu | ĭ̞ʊ | — | ɪ̯u̞ |

| ɪe | ie | ĭ̞e̞ | i̯ɛ | ɪ̯ɛ |

| ɪɐ | ia | ɪ̟̆a̽ | i̯a | ɪ̯a |

| ʊɔ | uo | ŭ̞o̞ | u̯ɔ | ʊ̯ɔ |

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c [22] | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɟ [22] | ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʂ | |||||

| voiced | dz | dʐ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʂ | x | |||

| voiced | v | z | ʐ | ɦ | ||||

| Approximant | plain | j | ||||||

| lateral | short | l | ʎ | |||||

| geminated | lː | |||||||

| Trill | short | r | ||||||

| geminated | rː | |||||||

- Voiceless stops and affricates are unaspirated.

- Voiced stops and affricates are fully voiced.

- /n/ is apical alveolar [n̺].[23]

- /c, ɟ/ are not always pure palatal plosives, but as the author describes, those are the ideal and standard sounds based on their main characteristics. [22]

- /t, d, ts, dz, s, z, ɲ/ are laminal [t̻, d̻, t̻s̻, d̻z̻, s̻, z̻, ɲ̻].[24]

- /t, d/ are alveolar [t, d] or denti-alveolar [t̪, d̪].[25][26]

- /ts, dz, s, z/ are alveolar [ts, dz, s, z].[27][28]

- Word-initial /dz/ occurs only in two words: dzekať and dziny.[19]

- /tɕ, dʑ/ are alveolo-palatal affricates that are often classified as stops. Their usual IPA transcription is ⟨c, ɟ⟩. As in Serbo-Croatian, the corresponding alveolo-palatal fricatives [ɕ, ʑ] do not occur in the standard language, thus making the system asymmetrical. The corresponding nasal is alveolo-palatal as well: [ɲ̟], but it can also be dento-alveolo-palatal.[29][30][31][32][33]

- /ʎ/ is palatalized laminal denti-alveolar [l̪ʲ],[34] palatalized laminal alveolar [l̻ʲ][19][34][35] or palatal [ʎ].[19][34][35] The palatal realization is the least common one.[19][35]

- Pavlík (2004) describes an additional realization, namely a weakly palatalized apical alveolar approximant [l̺ʲ]. According to this scholar, the palatal realization [ʎ] is actually alveolo-palatal [ʎ̟].[18]

- The /ʎ–l/ contrast is neutralized before front vowels, where only /l/ occurs. This neutralization is taken further in western dialects, in which /ʎ/ merges with /l/ in all environments.[19]

- /l, r/ are apical alveolar [l̺, r̺].[36]

- The retroflexes are less often realized as palato-alveolar [tʃ, dʒ, ʃ, ʒ].[19]

- /dʐ/ occurs mainly in loanwords.[19]

- /v/ is realized as:

- /j/ is an approximant, either palatal or alveolo-palatal.[39] Between open central vowels, it can be a quite lax approximant [j˕].[40]

Some additional notes includes the following (transcriptions in IPA unless otherwise stated):

- /r, l/ can be syllabic: /r̩, l̩/. When they are long (indicated in the spelling with the acute accent: ŕ and ĺ), they are always syllabic, e.g. vlk (wolf), prst (finger), štvrť (quarter), krk (neck), bisyllabic vĺča—vĺ-ča (wolfling), vŕba—vŕ-ba (willow-tree), etc.

- /m/ has the allophone [ɱ] in front of the labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/.

- /n/ in front of (post)alveolar fricatives has a postalveolar allophone [n̠].

- /n/ can be [ŋ] in front of the velar plosives /k/ and /ɡ/.

Stress

[edit]In the standard language, the stress is always on the first syllable of a word (or on the preceding preposition, see below). This is not the case in certain dialects. Eastern dialects have penultimate stress (as in Polish), which at times makes them difficult to understand for speakers of standard Slovak. Some of the north-central dialects have a weak stress on the first syllable, which becomes stronger and moves to the penultimate in certain cases. Monosyllabic conjunctions, monosyllabic short personal pronouns and auxiliary verb forms of the verb byť (to be) are usually unstressed.

Prepositions form a single prosodic unit with the following word, unless the word is long (four syllables or more) or the preposition stands at the beginning of a sentence.

Official transcriptions

[edit]Slovak linguists do not usually use IPA for phonetic transcription of their own language or others, but have their own system based on the Slovak alphabet. Many English language textbooks make use of this alternative transcription system. In the following table, pronunciation of each grapheme is given in this system as well as in the IPA.

| grapheme | IPA | transcr. | example |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | a | mama ('mother') |

| á | /aː/ | á | láska ('love') |

| ä | /æ/ | a, e, ä | mäso ('meat, flesh') |

| b | /b/ | b | brat ('brother') |

| c | /ts/ | c | cukor ('sugar') |

| č | /tʂ/ | č | čaj ('tea') |

| d | /d/ | d | dom ('house') |

| ď | /ɟ/ | ď | ďakovať ('to thank') |

| dz | /dz/ | ʒ | bryndza ('sheep cheese') |

| dž | /dʐ/ | ǯ | džem ('jam') |

| e | /e/ | e | meno ('name') |

| é | /eː/ | é | bazén ('pool') |

| f | /f/ | f | farba ('colour') |

| g | /ɡ/ | g | egreš ('gooseberry') |

| h | /ɦ/ | h | hlava ('head') |

| ch | /x/ | x | chlieb ('bread') |

| i | /i/ | i | pivo ('beer') |

| í | /iː/ | í | gombík ('button') |

| j | /j/ | j | jahoda ('strawberry') |

| k | /k/ | k | kniha ('book') |

| l | /l/, /l̩/ | l | plot ('fence') |

| ĺ | /l̩ː/ | ĺ | mĺkvy ('prone to silence') ⓘ |

| ľ | /ʎ/ | ľ | moľa ('clothes moth') ⓘ |

| m | /m/ | m | pomoc ('n. help') |

| n | /n/ | n | nos ('nose') |

| ň | /ɲ/ | ň | studňa ('n. well') |

| o | /ɔ/ | o | kostol ('church') |

| ó | /ɔː/ | ó | balón ('balloon') |

| ô | /ʊɔ/ | ŭo | kôň ('horse') ⓘ |

| p | /p/ | p | lopta ('ball') |

| q | /kv/ | kv | squash (squash) |

| r | /r/, /r̩/ | r | more ('sea') |

| ŕ | /r̩ː/ | ŕ | vŕba ('willow tree') |

| s | /s/ | s | strom ('tree') |

| š | /ʂ/ | š | myš ('mouse') |

| t | /t/ | t | stolička ('chair') |

| ť | /c/ | ť | ťava ('camel') |

| u | /u/ | u | ruka ('arm') |

| ú | /uː/ | ú | dúha ('rainbow') |

| v | /v/ | v | veža ('tower') |

| w | v | whiskey ('whiskey') | |

| x | /ks/ | ks | xylofón ('xylophone') |

| y | /i/ | i | syr ('cheese') |

| ý | /iː/ | í | rým ('rhyme') |

| z | /z/ | z | koza ('goat') |

| ž | /ʐ/ | ž | žaba ('frog') |

Sample

[edit]The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun. The transcription is based on a recording of a 28-year-old female speaker of standard Slovak from Bratislava.[41]

Phonemic transcription

[edit]/ˈras sa ˈseveraːk a ˈsl̩nkɔ ˈɦaːdali | ˈktɔ z ɲix je ˈsilɲejʂiː/

Phonetic transcription

[edit][ˈras sa ˈseʋeraːk a ˈsl̩ŋkɔ ˈɦaːdali | ˈktɔ z ɲiɣ je ˈsilɲejʂiː][42]

Orthographic version

[edit]Raz sa severák a slnko hádali, kto z nich je silnejší.[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pavlík (2004), pp. 93–95.

- ^ Short (2002), p. 535.

- ^ a b c d Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 375.

- ^ a b c d Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 376.

- ^ Short (2002), pp. 534–535.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), p. 64.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 57, 64–65, 103.

- ^ a b Pavlík (2004), p. 94.

- ^ a b Kráľ (1988), p. 55.

- ^ a b Short (2002), p. 534.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 93, 95.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 54, 92.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), p. 95.

- ^ a b Pavlík (2004), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 95, 97.

- ^ a b Pavlík (2004), p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 374.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 95–96.

- ^ Krech et al. (2009), p. 201.

- ^ a b c Pavlík (2004), pp. 99, 106.

- ^ Kráľ (1988:73). The author describes /n/ as apical alveolar, but the corresponding image shows a laminal denti-alveolar pronunciation (which he does not discuss).

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 72, 74–75, 80–82.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), p. 72.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 98–99.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Dvončová, Jenča & Kráľ (1969:?), cited in Hanulíková & Hamann (2010:374)

- ^ Pauliny (1979), p. 112.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 80–82.

- ^ Pavlík (2004:99–100, 102). This author transcribes the fricative part with ⟨ç, ʝ⟩, which is incorrect as alveolo-palatal fricatives can only be sibilant (thus [ɕ, ʑ]).

- ^ Recasens (2013), pp. 11, 13.

- ^ a b c Kráľ (1988), p. 82.

- ^ a b c Dvončová, Jenča & Kráľ (1969), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), pp. 78–79.

- ^ Kráľ (1988), p. 80.

- ^ Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), pp. 374, 376.

- ^ Recasens (2013), p. 15.

- ^ Pavlík (2004), p. 106.

- ^ Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 373.

- ^ Based on the transcription in Hanulíková & Hamann (2010:377). Some symbols were changed to keep the article consistent – see the section above.

- ^ Hanulíková & Hamann (2010), p. 377.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dvončová, Jana; Jenča, Gejza; Kráľ, Ábel (1969), Atlas slovenských hlások, Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied

- Hanulíková, Adriana; Hamann, Silke (2010), "Slovak" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 40 (3): 373–378, doi:10.1017/S0025100310000162

- Kráľ, Ábel (1988), Pravidlá slovenskej výslovnosti, Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo

- Krech, Eva Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz-Christian (2009), "7.3.15 Slowakisch", Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6

- Pauliny, Eugen (1979), Slovenská fonológia, Bratislava: Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo

- Recasens, Daniel (2013), "On the articulatory classification of (alveolo)palatal consonants" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 1–22, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000199, S2CID 145463946

- Rubach, Jerzy (1993), The Lexical Phonology of Slovak, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198240006

- Short, David (2002), "Slovak", in Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville G. (eds.), The Slavonic Languages, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 533–592, ISBN 9780415280785

- Pavlík, Radoslav (2004), Bosák, Ján; Petrufová, Magdaléna (eds.), "Slovenské hlásky a medzinárodná fonetická abeceda" [Slovak Speech Sounds and the International Phonetic Alphabet] (PDF), Jazykovedný časopis [The Linguistic Journal] (in Slovak) (55/2), Bratislava: Slovak Academic Press, spol. s r. o.: 87–109, ISSN 0021-5597

Further reading

[edit]- Bujalka, Anton; Baláž, Peter; Rýzková, Anna (1996), Slovenský jazyk I. Zvuková stránka jazyka. Náuka o slovnej zásobe, Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského

- Ďurovič, Ľubomír (1975), "Konsonantický systém slovenčiny", International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics, 19: 7–29

- Hála, Bohuslav (1929), Základy spisovné výslovnosti slovenské a srovnání s výslovností českou, Prague: Universita Karlova

- Isačenko, Alexandr Vasilievič (1968), Spektrografická analýza slovenských hlások, Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied

- Pauliny, Eugen (1963), Fonologický vývin slovenčiny, Bratislava: Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied

- Pauliny, Eugen; Ru̇žička, Jozef; Štolc, Jozef (1968), Slovenská gramatika, Slovenské pedagogické nakladateľstvo

- Rendár, Ľubomír (2006), "Dištinkcia mäkkeho ľ" (PDF), in Olšiak, Marcel (ed.), Varia XIV: Zborník materiálov zo XIV. kolokvia mládych jazykovedcov, Bratislava: Slovenská jazykovedná spoločnosť pri SAV a Katedra slovenského jazyka FF UKF v Nitre., pp. 51–59, ISBN 80-89037-04-6

- Rendár, Ľubomír (2008), "Hlasový začiatok v spravodajstve" (PDF), in Kralčák, Ľubomír (ed.), Hovorená podoba jazyka v médiách, Nitra: Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa v Nitre, pp. 184–191, ISBN 978-80-8094-293-9

- Rendár, Ľubomír (2009), "Fonácia a hlasové začiatky" (PDF), in Ološtiak, Martin; Ivanová, Martina; Gianitsová-Ološtiaková, Lucia (eds.), Varia XVIII: zborník plných príspevkov z XVIII. kolokvia mladých jazykovedcov (Prešov–Kokošovce-Sigord 3.–5. 12. 2008)., Prešov: Prešovská univerzita v Prešove, pp. 613–625

- Rubach, Jerzy (1995), "Representations and the organization of rules in Slavic phonology", in Goldsmith, John A. (ed.), The handbook of phonological theory (1st ed.), Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 848–866, ISBN 978-0631180623

- Sabol, Ján (1961), "O výslovnosti spoluhlásky v", Slovenská reč, 6: 342–348

- Tabačeková, Edita (1981), "Fonetická realizácia labiodentál v spisovnej slovenčine" (PDF), Slovenská reč, 46: 279–290

- Zygis, Marzena (2003), "Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Slavic Sibilant Fricatives" (PDF), ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 3: 175–213, doi:10.21248/zaspil.32.2003.191

KSF

KSF