Socialist Party of Washington

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 58 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 58 min

The Socialist Party of Washington was the Washington state section of the Socialist Party of America (SPA), an organization originally established as a federation of semi-autonomous state organizations.

During the 1910s, the Socialist Party of Washington was one of the largest state affiliates of the SPA in the Western United States, touting a membership which peaked with more than 6,200 paid members.[1] The Socialist Party of Washington is remembered today for its place in the free speech fights of the first decade of the 20th century, during which it was closely connected with the Industrial Workers of the World. It was also the organizational home of a number of key leaders of the early Communist Party of America.

Organizational history

[edit]Puget Sound Cooperative Colony

[edit]Washington was the home of a number of utopian socialist experiments in the 19th century, beginning with the establishment of Puget Sound Cooperative Colony near Port Angeles in 1887.[2] The project was established by Daniel Cronin, an organizer for the Knights of Labor, and George Venable Smith, an attorney – both new arrivals from California. Peter Peyto Good is also cited as a founder of the colony. Despite being progressive advocates of labor rights, Good and Smith were also instigators of anti-Chinese riots and they resented Chinese workers.[3] One hundred thousand dollars were raised through the sale of stock in the project, and 25 full blocks of land on the Ennis Creek platted for future expansion of Port Angeles were purchased from a son of the town's founder.[4]

On January 1, 1887, 22 members of the new community were on the town site, a number which had swelled to 239 six months later.[5] The aim of the community was to provide each newcomer with "shelter, food, and occupation", and by that summer rudimentary buildings sprung forth as members of the community worked as loggers, carpenters, farmers, cooks, and specialized professions.[6] Three pay grades were established for all workers, including officers of the colony, with payment made on the basis of an 8-hour workday (6-hour for women). Payment was made in colony scrip, with legal tender reserved for the colony's purchases from the outside world.[7] The colonists worked furiously to construct their own community from nothingness.[citation needed]

By the coming of winter, the deficiencies of the colony became apparent. Money pledged for the purchase of stock had not come in, housing was inadequate, and expenses of nearly $200 a day drained the colony's resources. Disillusionment set in among many of the participants that the enterprise, far from establishing a cooperative community of secure work and plenty, was little more than a land speculation scheme in a new guise.[8] If this was not the original intent of the founders, within two years it became the practical reality of the enterprise, as the colony platted an overlooking bluff and sold lots there to outsiders as part of a subdivision called "Edgewood".[9] Amidst squabbling over finances and a shortage of ready cash, a wave of lawsuits ensued with 336 legal claims filed against the heavily mortgaged colony and its 196 separate notes and debts.[10] Liquidation and the settlement of claims took nearly a decade.[citation needed] The last surviving member of the colony, C. S. Stakemiller, died in 1958.[11]

Equality Colony

[edit]

If the Puget Sound Cooperative Colony was a matter of local import, a somewhat later attempt at socialist colonization of Washington by the Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth drew national attention. As early as 1894 the idea had been floated among Eastern socialists that one possible means for achieving a socialist society would be to flood a single state of the union with organized socialist colonies.[12] They argued that, through practical experience, the superiority of socialist organization of production and distribution and the virtues of pure democratic government would be demonstrated to hesitant Americans. Once the case was proven in one state, and its elected government won by socialist political candidates, the example would spread to neighboring states and across America, ushering in the Cooperative Commonwealth in America, its participants hoped.

Discussion of this idea began to take place in earnest in the pages of the pioneer radical publication The Coming Nation, published by J.A. Wayland, forerunner of the popular Kansas weekly The Appeal to Reason. By the fall of 1895, a concrete proposal had begun to take shape, advanced by Maine resident Norman Wallace Lermond – a disciple of Edward Bellamy and Laurence Gronlund.[12] Lermond called for the formation of a membership organization to carry on such a colonization program in an unnamed Western state, and he issued a call in the pages of the socialist press for a convention to establish a new organization called the Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth (BCC). This call was endorsed by an impressive list of 143 of the nation's leading social reformers, including the journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd, union organizer Eugene V. Debs, and religious leader Rev. William D.P. Bliss.[12]

From July 24–26, 1896, an organizational convention for the BCC was held in St. Louis, Missouri, site of a simultaneous gathering of the People's Party, the so-called "Populists". It was hoped that by holding the BCC convention at the same time and place, a large pool of like-minded persons would be assured.[13] However, the Populist convention proved to be a protracted and contentious affair, as the people were divided over the question of endorsement of Democrat William Jennings Bryan; this absorbed the attention of Lermond, Maine's People's Party delegate.[14] The BCC convention was effectively reduced to an announcement of candidates for officers and the construction of a constitution to be voted on by mail.[15]

Officers were elected on September 19, 1896, a list which included Debs as organizer. He converted to the ideas of socialism while in jail as a result of the 1894 Pullman Strike, and he also saw in the BCC's colonization plan a possibility for gainful employment for railroad workers blacklisted for membership in his failing American Railway Union. (ARU)[16] The Coming Nation continued to beat the drum of publicity for the project.[citation needed] The colony in Skagit County, near the small town of Edison, was established in the November 1897.[17] Three members of the "Equality" colony would go on to become important leaders in the early Socialist Party of Washington — Harry Ault, an associate editor of The Socialist and later editor of the Seattle Union Record; George Boomer, a left winger who was the first representative of the SPW to the National Committee of the Socialist Party of America; and David Burgess, an organizer in the early days of the party and later State Secretary of the organization.[18]

Burley Colony

[edit]

While supportive of the idea of socialists targeting a single state for colonization, Eugene Debs was also committed to building a political party. The scheduled June 1897 convention of the ARU in Chicago proved to be the group's last. On Tuesday, June 15, a speech by Debs began a three-day summation of the union's activities and a wrapping up of loose ends. Three days later, the organization formally declared itself the Social Democracy of America and opened its doors to outside participation, including representatives of the Socialist Labor Party of America, its trade union arm the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance, the Scandinavian Cooperative League, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, the Chicago Labor Union Exchange, and other groups. The gathering adopted a declaration of principles and elected officers, with a 5-member Executive Board which included Debs as governing chairman of the organization.[19]

The Social Democracy of America was initially oriented towards a policy of colonization; they named a 3-member "Colonization Committee" on August 1, 1897, consisting of Col. Richard J. Hinton (Washington, DC), Wilfred P. Borland (Bay City, MI), and Cyrus Field Willard (Chicago, IL). This trio moved their focus for a colony to seed the future "Cooperative Commonwealth" from Washington state to the Cumberland plateau of Tennessee.[20]

At its so-called "First National Convention" in June 1898, the Social Democracy of America split over the colonization issue, with Debs and his brother Theodore, Victor Berger, and others bolting the gathering to establish the Social Democratic Party of America. The majority of the Social Democracy plowed ahead with their colonization scheme, turning their focus once again to Washington state.[citation needed] They assigned Cyrus Field Willard the task of locating a site for their initial colony and gave him authority to "do what in his judgment appeared the right thing to do."[This quote needs a citation]

Willard went to Seattle to consult with SDA member J.B. Fowler, who pointed out the good harbors on southern Puget Sound. There they found Henry W. Stein, who was sympathetic to them politically and had just become the executor of land in rural Kitsap County that was open for sale. In September 1898 the SDA re-incorporated in Seattle as the Co-Operative Brotherhood and on October 18 they purchased 260 acres (1.1 km2) for $6,000. The first colonists arrived on October 20, 1898.[21]

By 1901 the colony had grown to include 115 participants, including 45 men, 25 women, and 45 children.[22] This group living at Burley was supported by a network of about 1,000 others nominally participating in the organization off site.[22]

Originally named "Brotherhood", the inhabitants gradually began to refer to it as "Burley" after the nearby Burley creek. A colony scrip was created that included a $1 denomination for an eight-hour work day and smaller units, called minims, for minutes worker over or less than six hours.[23] "Circle City" was the informal name of a group of buildings near the water.[24]

The colony subsisted on agriculture, fishing and logging; they also made income selling cigars, jam, subscriptions of its magazines, and membership in the B.C. It rented out use of its mill and rooms in its "Commonwealth Hotel" for visitors.[25] The colony's newspaper, the Co-operator stayed in publication from December 1898 to June 1906. Originally an 8-page weekly, it changed to a 32-page monthly in 1902 and to a 16-page magazine in October 1903.[26]

The colony went into decline in the early twentieth century. In December 1904 some members abandoned the communal concept and reorganized as the Burley Rochdale Mercantile Association, and three months later the Co-operative Brotherhood itself re-organized into a joint stock company. By 1908 there were 150 members of the Brotherhood, only 17 of them residents of the colony. The trustees called a meeting of stockholders to dissolve the Brotherhood in late 1912, but it lacked the two-thirds majority, whereupon those who were in favor of disbanding took the company to court. On January 10, 1913 Judge John P. Young ordered the Cooperative Brotherhood dissolved and put its assets into receivership. The last of its properties were sold off in 1924.[27]

Establishment

[edit]Social Democracy of America

[edit]The Social Democracy of America (SDA), established in 1897 from the remnants of the American Railway Union headed by Eugene V. Debs, maintained an existence in the new state of Washington, with Washington Local Branch No. 1 established in the town of Palouse. Washington Local Branch No. 3, based in Seattle, was the most important of the fledgling local organizations in the state, holding Tuesday evening meetings at 1118 Third Avenue.[28] The Seattle branch included both male and female members, including two women who played mandolin and guitar for the well attended meetings each week.[28]

Under the constitution of the SDA, the various local branches of Washington state would have been organized under the aegis of a superior body called the "State Union," a sort of state executive committee including one representative from each local branch in Washington that would have met annually on the first Tuesday in May.[29]

Social Democratic Party of Washington

[edit]By 1900, the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP) was established in Washington, probably as a continuation of a previously existing Socialist Labor Party organization in the state. The Washington state organization was affiliated with the faction of the SDP based in Springfield, Massachusetts, a national organization which had sprung from those SLP dissidents who had seceded in 1899 over the issues of inner-party democracy and trade union tactics.[30] In 1900, the SDP of Washington held a founding convention which composed a Washington state platform endorsing "the principles of international Socialism, based on the irrepressible struggle of wage-labor against modern capitalism" and expressing approval of the nomination of the Debs-Harriman ticket for President and Vice President.

Candidate Debs mutually admired the Washington Socialists, proclaiming in a March 1900 article in the Appeal to Reason that the Social Democratic Party's progress had been "the greatest in the states of Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and Washington" and declaring that "these three states are marked for early conquest."[31]

The vision of the Washington Socialists was particularly radical. No ameliorative reforms whatsoever were part of the 1900 Washington platform, which declared:

We are fighting for no half-way measures. We will not be content until every workingman understands how he is exploited and robbed by the capitalist and understands also that he has an immediate weapon in the ballot whereby to achieve his own emancipation.

We propose to show every worker with hand or head that he is being expropriated by his capitalist masters, and that the time has come when the expropriators must be expropriated.[32]

While the great majority of Washington socialists supported the Springfield Social Democratic Party, an effort was made by the rival Chicago party to organize "loyal members," with the effort conducted by L.W. Kidd of Seattle,[33] thereby establishing for a time parallel party organizations.

A full slate of state candidates were put forward by the SDP in the fall of 1900, headed by Seattle carpenter W.C.B. Randolph for Governor and William Hogan of Equality Colony and Dr. Hermon F. Titus of Seattle for Congress.[34] The SDP of Washington was governed by a five-member State Executive Committee, with State Treasurer Ida W. Mudgett of Tacoma handling the distribution of membership cards and dues stamps.[35] State Secretary was J.D. Curtis and State Organizer was Hermon F. Titus. The SDP boasted 32 locals in the state early in 1901.[36]

The SDP of Washington held a second (and final) state convention at party headquarters, located at 220 Union Street in Seattle, on Sunday June 30. Delegates were present representing 16 locals of the Washington party.[37] At this gathering E. Lux of Whatcom was selected as the representative of the party to the Socialist Unity Convention in Indianapolis in August. The convention opined in favor of the name "Socialist Party" and instructed Lux "to vote first, last and all the time for organic union of the Socialist movement of the United States; and also to vote for the elimination from our platform of all immediate demands and to confine it to a plain statement of our aims and objects".[38] A new five member State Committee was elected which included four members from Seattle and one from the town of Fairhaven, Washington.[37]

Birth of the unified party

[edit]

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was established in August 1901 at a "Socialist Unity Convention" which brought together the Chicago-based Social Democratic Party headed by railroad union organizer Eugene V. Debs and socialist newspaper publisher Victor L. Berger with a similarly named East Coast organization of expatriates from the Socialist Labor Party, featuring prominently Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit. United by a distaste for the centralism and enforced uniformity of the Socialist Labor Party of Daniel DeLeon, the new SPA was founded on the principle of "state autonomy" – a federation of state organizations each conducting their own electoral and educational affairs as they best saw fit, while combining under a national umbrella for presidential campaigns and major political projects.[citation needed]

The foundation of the new SPA in 1901 "rebranded" the already-existing socialist movement in Washington state as the Socialist Party of Washington (SPW). A formal charter was granted to the state organization in the last days of September 1901.[39] For all the national hoopla, the size and structure of the local groups themselves experienced very little in the way of fundamental change under the banner of the "new" party.[40] By the end of 1902, the SPW consisted of approximately 45 locals and 1,000 members,[41] and by the spring of 1904, a total of 55 locals had been established, with the largest of these, Seattle, incorporated into no fewer than 7 branches.[42]

The SPW's first plunge into electoral politics came in the fall of 1901, when two party members, medical doctor-turned-radical newspaper publisher Hermon Titus and John T. Oldman, ran for the King County Board of Education in Seattle. Together the pair received about 25 percent of the vote in a losing effort.[43] By 1904, the Washington Socialists were sufficiently organized to run a practically full slate, with 55 of the organization's members standing as candidates for various state and county offices.[43]

From its earliest days, the Socialist Party of Washington was divided along factional lines between those who saw electoral politics as the direct means for the working class and its allies to gain control of the political system and to thus establish socialism as opposed to those who harbored few illusions about the efficacy of elections and who instead viewed the electoral process as a means of bringing socialist ideas to erstwhile voters on the road to a future socialist revolution. The electorally oriented, moderate faction described themselves as "constructive socialists," while besmirching their opponents as "impossibilists", whereas the more radical and confrontationalist faction self-described as "Reds," while denigrating their inner-party foes as "Yellows."[44] The history of the SPW over its first two decades proved to be an almost ceaseless bedlam of factional warfare between these two groups.[citation needed]

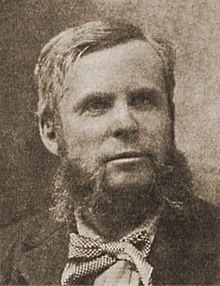

The radical faction was centered around Hermon F. Titus, born in 1852 and an 1873 graduate of Madison University and later its theological seminary. After graduating the seminary, Titus had spent over a decade as a Baptist preacher in Ithaca, New York and Newton, Massachusetts before leaving the church owing to feelings that it did not adequately represent the teachings of Jesus. Thereafter, Titus decided to become a medical doctor, enrolling in Harvard Medical School, from which he graduated in 1890. Upon graduation, Titus practiced medicine for two years in Newton before moving to Seattle in 1892, where he continued to work as a medical practitioner for the rest of the decade.[45]

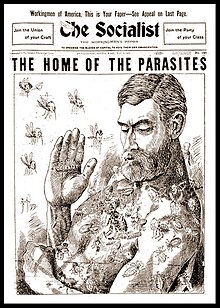

In the Pacific Northwest, Titus' interests turned towards politics, and he established an independent "Seattle Citizens' Movement" in 1900, turning to the Social Democratic Party and their successor, the Socialist Party, when that attempt failed to garner enduring support.[45] On August 12, 1900, he launched Seattle's first explicitly socialist weekly newspaper under the simple and direct title The Socialist. He quickly became an aggressive opponent of the neo-Populist agrarian-oriented socialism professed by J.A. Wayland and his newspaper, The Appeal to Reason, and soon became a leading national voice for a more assertive "proletarian" orientation.[45] Young enthusiasts gathered around Titus and his newspaper, with him continuing to play the role of leader of the SPW's "Red faction" until about 1909.[46] He aggressively hammered those whom he deemed insufficiently stalwart in their commitment to revolutionary socialism, running on his front page the fire-breathing 1903 platform of Local Seattle next to the civic reform-oriented platform of Local Spokane under the headings "As Much Socialism as Possible" and "As Little Socialism as Possible," respectively.[47] Public ridicule of this sort at the expense of erstwhile comrades did little to advance the goal of a united Socialist Party of Washington. To his supporters, on the other hand, Titus's unflinching salvos at the temporizing half-measures of others were red meat for the faithful.[citation needed]

The Socialist Party of Washington did not limit itself to dry group meetings and polemicizing in the party press. Special events such as May Day were the cause for mass meetings with a parade of energetic speakers who stirred the juices of the crowd.[48] Dances were sponsored regularly on Saturday night in Seattle, at which young Socialists could socialize, and the effort was made to put together a Socialist orchestra and a Socialist choir.[48] Such activities doubtlessly helped to foster unity within the state's numerically dominant Seattle local.[original research?]

Factional war commences

[edit]

No amount of vocal harmonizing could hide the fact that the Socialist Party of Washington was the venue for an ongoing factional war between one-step-at-a-time moderates and workers-of-the-world-unite radicals, however. In the election of 1902, two members of the moderate Local Spokane were elected to public office under the banner of the Democratic Party. The pair dutifully resigned from the Socialist Party, which prohibited membership in any other political organization owing to the bitter experience of the People's Party ("Populists") whom, it was believed, had destroyed their organization through political "fusion" with the Democrats. Local Spokane refused to accept the resignations of its newly elected Democratic members, however, prompting a party crisis.[citation needed] A referendum election was launched calling for the revocation of Local Spokane's SPW charter by the State Committee. On April 18, 1903, Local Spokane's charter was pulled by the organization by a vote of 164–87. Most locals were unanimous one way or the other on the question; the Finnish Branch of Local Seattle, half of Central Branch Seattle, Local Tacoma, and several Eastern Washington branches joined Local Spokane in its losing effort to avoid disestablishment.[49]

Similar action against "fusionism" was taken against Local Northport, a town located in Northeastern Washington, which likewise had its charter revoked for collaboration with another party during the 1902 campaign. In a third action, Thomas Neill, the newly elected city prosecutor of Colfax suffered a more severe fate via referendum vote, as he was expelled from the party for violation of the group's constitution when he accepted nomination for office independently of the SPW.[49] Voting in all three of these actions against "fusionism" by Eastern Washington locals and individuals was similar, coming down approximately 2-to-1 in favor of sanctions; locals largely cast their votes en bloc one way or the other, with Eastern Washington and Seattle's Finnish branch supporting the moderates' pro-"fusionist" position, while locals in Western Washington tended to back the radicals' demand for sanctions.[citation needed]

Despite having one three referendum victories on matters of "political fusion", Titus was enraged by the method of reorganization put in place by the State Executive Committee, which instead of following the direction of the referendum "that an organizer be sent to organize a Local of such members as believe in the uncompromising and independent political action of the Socialist Party", instead elected to issue a call for new applications for a charter from both cities. The Local Quorum [Executive Committee] of the State Committee had "not obeyed the will of the party expressed in its highest form by a deliberate Referendum", Titus declared.[49] This criticism caused a quick reversal by the Local Quorum, which caused left wing State Secretary U.G. Moore to state in The Socialist on June 2: "I want to apologize to the comrades of the state for any part I took in such action."[50] The other two members of the Local Quorum, the moderates William McDevitt[51] and Scott, held a session in State Secretary Moore's absence and appointed H.B. Jory, an opponent of the sanctions against Locals Spokane and Northport, as the special organizer in charge of reestablishing the two groups. This action fulfilled the directive of the party referendums while at the same time attempting to subvert its intent, Titus charged.[52] Jory declined to perform the reorganization demanded of him, however, forcing the Local Quorum to make another selection for the reorganization, that being J.H.C. Scurlock of Dupont, Idaho.[53]

Decline and move of Titus' newspaper

[edit]As his anger with the State Committee for its failure to decisively cleanse the SPW of the friends of "fusionism" in Eastern Washington, Titus began to show signs of dissatisfaction the financial drain from The Socialist. In a handwritten appeal "To All Friends of The Socialist" (May 20, 1903) and reproduced in facsimile in the paper's pages, Titus announced that with the third anniversary of his publication in the offing, circulation remained stuck at 7,000 copies.[54] He announced:

It is not enough to pay expenses. I have given my services freely for three years, besides meeting all deficits. If you want this paper to continue, you must lend a hand and increase its circulation to Twenty Five Thousand before Aug. 12th. Our working class policy has made enemies who are working to kill the paper. Will its friends stand pat?[54]

This began a year of financial difficulty for the publication as some in the Washington Socialist movement moved to distance themselves from the radical Seattle paper. Part of Titus' financial difficulty was beyond the factional division of the Socialist Party of Washington and instead was related to Titus' stubborn insistence on maintaining a nominal subscription rate of just 50 cents per year, an artificially low price which mandated mass circulation akin to that of his rival, Wayland's Appeal to Reason: Titus declared it essential for his paper to expand to the 25,000 subscriber mark in order to survive at the current subscription rate.[55] While this circulation target was not reached, The Socialist nevertheless managed to weather its difficult economic position for another year.[citation needed]

The paper's financial crisis came to a head in the summer of 1904. Effective with its June 26, 1904 issue, The Socialist abruptly shifted from a heavily illustrated 4-page format to a sparse 2-page sheet, running a headline on the front entitled "Shall The Socialist Live or Die?" This article noted that, while the publication had been basically covering its expenses over a period of several months, for the past two months the publication had suddenly begun running at a deficit of $100 per month, an amount deemed unsustainable by the 35 members of the "Socialist Educational Union" headed by Titus back of the publication.[56] Noting that the circulation of the paper now stood at around 5,000 regular subscribers, with bundle orders of special issues occasionally pushing the total as high as 12,000, the article outlined the situation for the publication's readership:

Our expenses have been kept down to the lowest possible notch consistent with the high standards of the paper. Our paper has been purchased by the ton so as to get low rates. The lowest bidders for our printing have always had the contract. Almost nothing has been paid for salaries, the three comrades who have worked in the office at times the last year getting only five dollars a week and a bed. Our high item of expense has been our cartoons.... We have had on our staff about all the successful cartoonists among the Socialists, and many of these have contributed their work without pay. But our engraving comes high and at a price.[56]

While readers were encouraged to make the publication sustainable through a fourfold increase in circulation, switch to a subscription rate of $1 per year was openly mooted.[citation needed]

The subsequent issue featured an article by Debs titled "To The Socialist and its Readers," in which the party's leading orator came down firmly in support of a rate hike. Debs decried the inconsistency of Socialists who "talk continually about 'education' while they let their own press starve to death" and noted that The Socialist, at a rate of 50 cents per year, "cannot pay legitimate expenses". Debs added, "I want to see a substantial paper, the best that can be produced, and a reasonable price paid for it, instead of a flimsy sheet on crutches that manages to limp from one issue to another like a walking epitaph."[57] Then, in August 1904, at the semi-annual meeting of the Washington Socialists who assisted Titus with the publication of The Socialist, a different solution to the financial problem was chosen. They decided to change the name and focus of the publication, thereby boosting circulation to a level which could sustain the 50 cent subscription rate. Effective September 1, 1904, it was announced that the name of The Socialist would change to Next, and its orientation would change from a party paper "published for Socialists first" to a propaganda paper "published primarily for non-Socialists".[58] Titus declared:

For four years The Socialist, or The Seattle, as so many comrades call it, has fought squarely against all middle class tendencies in the party. This paper has borne a conspicuous part in driving all such tendencies to the read. Now that they ware in the rear and the working class elements represented by [Socialist Party ticket heads] Debs and Hanford are in full control, the mission of The Socialist may be considered fulfilled.[58]

The interlude of Titus' paper as Next proved to be short-lived, however. On March 18, 1905, Titus' paper reemerged in Toledo, Ohio as a "party paper" called The Socialist. In this new permutation of his publishing project, Titus joined with William Mailly, former Executive Secretary of the Socialist Party and a left-winger in political temperament who had been replaced by centrist J. Mahlon Barnes on February 1 that same year.[citation needed] Although the new Ohio incarnation of The Socialist continued to give a place to news of the Socialist Party of Washington, the organization felt its loss. A referendum was subsequently conducted amongst the SPW's membership in 1905 on the question of whether a party-owned paper should be established – a proposal which carried by a majority of 70 votes.[59]

Parallel party organizations emerge

[edit]

While Hermon Titus sought an enlarged press run and a national role for his weekly newspaper and stood satisfied with the 1903 battle against so-called "fusionism" culminated by victory at the July 1903 State Convention, the moderate wing of the party continued to battle for its own vision of socialism. Winning majority control of Central Branch of Local Seattle — one of 7 branches in the city, albeit the largest — William McDevitt and his associates brought Walter Thomas Mills to town on a speaking engagement in July 1903. Mills was anathema to Titus and the left wingers around him, depicted as a devotee of middle class reformism and regarded by one historian of the period as an oratorial gun for hire used by moderate factionalists in various states to rally the troops.[60]

After hearing Mills' presentation, a committee of the Local Seattle, Central Branch, headed by McDevitt, drafted a resolution endorsing Mills as "an uncompromising, class-conscious, and revolutionary Socialist" and upbraiding Hermon Titus's newspaper for participating in a "plan to silence Mills by driving him off the Socialist lecture platform, and by blacklisting him in the eyes of the Socialist Party."[61]

This proved to be a red flag to the Reds. Titus railed against "the Mills men" using "packed" meetings to gain control of the Central Branch and the Seattle City Central Committee in the absence of other delegates. "They will stop at nothing in the way of injustice," Titus indignantly proclaimed.[61]

Local Seattle remained divided between radical and moderate socialists, with some branches, such as the Pike Street Branch, dominated by the left wing, while others, such as the Finnish branch, were firmly on the side of the centrist forces which had steadily come to dominate the national Socialist Party. The situation seems to shown signs of developing into two parallel organizations, one dedicated to agitation, propaganda, and the cultivation of the working class into the SPW, the other devoted to trying to build a successful electoral organization by building a multi-class alliance around common desires.

Birth of the IWW

[edit]The birth of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1905, espousing the notion of "One Big Union" of all the workers, organized according to industries in accord with the principles of industrial unionism, excited a portion of the membership of the Socialist Party of Washington. As early as January 1906 the idea began to be voiced among some of the left wing of SPW that the organization should go on the record as endorsing the new alternative to the American Federation of Labor (AF of L), an alliance of craft unions together with state and local labor federations. This potentially divisive groundswell of support for the fledgling IWW prompted influential left winger Alfred Wagenknecht to make an impassioned case for neutrality to the party press:

The IWW and AF of L are economic organizations. They are not political. They do not and should not enter the field of politics. Their membership is not pledged to support any particular political party. It is safe to say that part of the membership of both organizations is not revolutionary, knows nothing about abolishing the wages system, and is not class conscious politically.

The question is not whether or not the IWW is a better organization than the AF of L. It is not a question of whether or not the Socialist Party needs an economic organization to help accomplish the revolution. It is a question of whether or not the Socialist Party as a political organization is going to violate the reason for its existence and endorse an unknown political quantity, be it IWW or AF of L.[62]

Moderates capture Local Seattle

[edit]

In 1905 came a movement in Local Seattle to adopt a new constitution, breaking up the branches as previously constituted in favor of branches according to electoral districts, combined with the Local taking possession of all property belonging to the various branches.[63] This proposal was bitterly fought by Titus and the Pike Street Branch, which actively campaigned for defeat of the proposal, including at attempt to get members who had already voted in favor of the measure to retract their votes. When the Seattle City Central Committee refused to provide adequate ballots for this purpose to the Pike Street Branch, Titus had small forms printed declaring the intention of the signatory to vote against the proposal. This provoked Titus's enemies in Central Branch of Local Seattle to prefer charges against Titus and the Pike Street Branch for election fraud for this and other smaller technical matters.

When Titus was cleared of these charges at a meeting of the full Seattle City Central Committee, a heated gathering which lasted 7 hours, Central Branch launched a statewide referendum vote against Titus. This vote closed on June 1, 1905, and exonerated Titus by a vote of 4-to-1. Of the 41 votes cast against Titus in the state, fully 35 came from Seattle Central Branch.[64]

Despite loss of their proposed bylaws revision by referendum vote, the moderate faction of Local Seattle made use of the City Central Committee to nevertheless abolish branch organizations in the fall of 1905. "This practically puts control of [the] Local into hands of [a] small number of people who can and will attend meetings and who live close to meeting place," a representative of the left wing charged.[65]

The moderates attempted to further expand their control of the Washington organization in November 1905 with a proposal to the State Quorum that Local Seattle effectively take over the State Office, eliminating the salary attached to the State Secretary's position and vacating state headquarters in the name of economy. Corinne Wolfe of Local Seattle would thereafter effectively perform the duties of Secretary-Treasurer, until such time that the party emerged from indebtedness. This proposal was defeated by the Local Quorum by a 4–1 vote.[66]

With the State Secretary's position, and majorities of the State Committee and the Local Quorum ensconced in the hands of the left wing, the moderate faction seems to have engaged in a program of passive resistance. The February 1906 monthly meeting of the Local Quorum, amid charges of misadministration levied by moderate-dominated Local Seattle, read a report from Local Mt. Pleasant indicating that they would no longer pay dues to the State Office, instead retaining the funds for use on propaganda activities in their own vicinity.[67] Meanwhile, State Secretary-Treasurer Martin reported that only 29 locals — about half the total — had filed their monthly reports for January. Paid membership stood at just 615, with more than half the state organization, 942 members, standing in arrears.[67] For their part, the left wing majority kept the pot boiling by launching an investigation of Tacoma moderate Irene Smith for having allegedly declared in a Socialist stump speech that the platform of New York Mayoral candidate William Randolph Hearst was "good enough for any Socialist."[68]

The left strikes back

[edit]

With the semi-autonomous Pike Street Branch effectively shut down by the moderate-controlled Seattle City Central Committee it seems that a number of left wing stalwarts redirected their attention to Everett, the headquarters city of the SPW. Everett was a mill town situated 25 miles (40 km) north of Seattle and the county seat of Snohomish County — a sufficient distance for the "Reds" to dodge any bureaucratic machinations of the now dominant Central Branch moderates. Local Everett became the de facto new Pike Street Branch, with reports regularly made to Hermon Titus's weekly detailing their exploits.[69]

Throughout the ensuing years a sort of "dual power" would exist in the state, pitting Seattle moderates and Everett radicals.

While moderate Central Branch successfully used the cudgel of the Seattle City Central Committee to eradicate the left wing Pike Street Branch, eliminating Branches and thus gaining control of Local Seattle, they were by no means victorious. The left wing retaliated in a similar manner, making use of their 4-1 majority of the Local Quorum, the de facto State Executive Committee, and a comfortable majority of the State Executive Committee, to take action against Local Seattle.

The pretext for the charges against Local Seattle involved allegations that three of its members had on January 20, 1906, signed fictitious names to a pledge to support the new Seattle "Municipal Ownership Party" so as to be able to attend its convention — seen as a clear act of "political fusionism." The three did not deny this activity but claimed that by signing false names they did not violate their pledge to support exclusively the Socialist Party.[70]

Charges had been preferred against the trio involved by Local Everett, but Local Seattle had refused to take action against them, thereby opening themselves as a unit up to charges of unconstitutional behavior.

At the April 8, 1906 the regular weekly meeting of the Local Quorum met in Everett. Quorum member Alfred Wagenknecht made application to transfer his status from Local Seattle — which was facing suspension for "condoning political compromise"— to member-at-large status. After discussion, this proposal was accepted, with Quorum member J.C. Robbins giving notice that he would appeal the decision to the rank-and-file membership via a state referendum.[71]

At this same meeting it was announced that a vote of the State Committee revoking the charter of Local Seattle had passed. The decision was appealed to the membership of the party by referendum vote.

On Wednesday, April 11, a meeting of moderate Local Seattle was held at which an answer to the left wing State Committee was discussed. The group also began publishing a weekly bulletin in order to present its side of the case, attempting to demonstrate that a "conspiracy" was at work backed by Hermon Titus.[70]

At the meeting of April 22, 1906, it was announced that an application for a new charter for Local Seattle had been made by J.H. Steele and 32 additional applicants. Robbins moved that no charter be granted while a referendum was pending on the status of the charter of the old Local Seattle. A substitution motion was made by Elmer Allison recognizing the new application. A "general and vigorous discussion, participated in by members of the quorum and visitors" followed, with Allison's substitute motion passing. The Secretary of the new, left wing Local Seattle was Annie I. Steele, with William Cook the organizer.[72]

Late in 1906, moderate forces in the party persuaded Hermon Titus's old nemesis, Walter Thomas Mills, to leave Chicago to take charge of their efforts in Washington to win control of the party.[73] Mills relocated to Seattle and in the next year began publication of a newspaper reflective of the views of the "constructive Socialists," the blandly named Saturday Evening Tribune.[73] Mills advocated the adoption of a "good government" program by the SPW in lieu of the divisive "free speech" fight being waged by the left, seeking to win the support of "solid, earnest citizens" instead of limiting the party's appeal to the unemployed and the working class.[73]

Titus's paper The Socialist had returned to the city at this time, with Alfred Wagenknecht, formerly the first paid Secretary of Local Seattle, leaving to join The Socialist as its Business Manager.[74]

In February 1907, the Socialist Party of Washington was able to report that the new reorganized Local Seattle had grown to a membership of "over 300." The party's Finnish Branch had built a new hall on a lot on the corner of Madison Street and Washington Boulevard which had been purchased for the purpose.[74]

A new constitution for Local Seattle was voted upon in February 1907. The new constitution abolished the unified City Central Committee in favor of five Central Committees, four specialized groups including one member from each electoral Ward Branch and a "Trustees Committee" of 5 elected by referendum vote of the entire Local.

The Trustees Committee was the de facto Executive Committee in the new scheme, holding all property, auditing all accounts, conducting referendums, electing the Local Secretary, and transacting all business with other Locals as well as the state and national party organizations.[74] The only constraint upon its powers was to be a monthly "Mass Convention" of the general membership of Local Seattle.[74]

At the time of the 1907 constitutional revision, Local Seattle consisted of 12 Ward Branches and a Finnish Branch. The Ward Branches met on various nights of the week, according to local preference, Sunday night at 8 pm reserved for a general propaganda meeting to which the public was invited, held at the "Socialist Temple" at the corner of 4th and Pine.[74]

The Mills affair of 1907

[edit]The arrival of Walter Thomas Mills as a Seattle resident in 1906 energized the embattled moderate faction. Throughout early 1907 Mills conducted Sunday afternoon meetings independent or the regularly scheduled Sunday afternoon propaganda meetings of Local Seattle, using these gatherings as a means of making contact with Socialists discontented with the left wing state organization and leadership of the reorganized Local Seattle.[75] The faction, which included many of those expelled from Local Seattle in 1906 for "fusionism," organized itself as the Propaganda Club of Seattle, which Mills persuade to rejoin the organization en bloc.[75]

The situation was complicated in March 1907, when Mills was charged by the British Columbia Dominion Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of Canada with having advocated "compromise and fusion" in a speech delivered in Victoria on December 28, 1906, in which Mills urged support of the Canadian Labor Party. Having gotten wind of Mills' heresy, Local Quorum member Alfred Wagenknecht wrote to the BC Dominion Executive Committee on February 20, 1907, encouraging them to file a complaint against Mills.[76] The Dominion Executive Committee complied on March 6 with a letter to the Washington State Executive Committee making complaint about Mills. This led to charges being preferred against Mills, with Local Seattle placed under the shadow of perhaps once again facing the loss of its charter if it failed to take action on the matter.[75] Both sides began to organize frantically for the May Washington State Convention, which was seen as the means by which the dilemma could be overcome by Mills forces — a majority at the convention for the moderates would mean a new State Committee and an end to pressure.

Mills and his close associate A. Hutchinson put forward full slates of 20 delegates and 20 alternates at the meeting of Local Seattle held in April to select delegates to the forthcoming state convention.[77] A so-called "No Compromise Slate" was put forward in opposition to the moderates, a ticket which combined the forces of the left wing and the Finnish Branch, which was allotted 4 of the 20 delegates in play by previous agreement.[77]

Sensing imminent defeat, the Mills forces fought for two hours to shut out the Finnish attendees, who had been unable to obtain dues stamps despite assurances of the branch secretary as to their current status as fully paid members, but heated debate and a series of parliamentary maneuvers were narrowly defeated again and again by the left wing. Finally at 2 pm a final vote was taken, with the "No Compromise Ticket" defeating the Mills-Hutchinson "List of Delegates" 81 to 72, with 5 more ballots cast for the "No Compromise" slate sans two or three candidates.[77]

With his ticket defeated and no hope in delay for a new State Committee, Mills was brought to trial before the Local Seattle on Sunday, April 28, 1907 at 10 am on the Victoria speech.[78] Before the largest mass meeting of Local Seattle in the organization's history, charges were read by J.G. Morgan, Secretary of the Socialist Party of Canada. Mill pleaded "not guilty" and the point was reached where Morgan was to make his opening statement and to introduce his evidence. Suddenly, Mills was given the floor and he made a motion of adjournment, which was quickly seconded and carried amid the whooping and shouting of his supporters.[79]

The point should be emphasized that although the revolutionary socialists had pulled the charter of Local Seattle and "reorganized" it in April 1906, within a year the moderates had once again achieved primacy — a point emphasized by Harry Ault in his June 1, 1907 column, in which he lamented the "steadily diminished" crowds being drawn by Local Seattle to its regular Sunday evenings propaganda meetings. These meetings had been undercut by the heavily promoted Sunday afternoon sessions of the Mills faction, Ault believed. "This is a great setback from the time when the revolutionary element had absolute control in the party some four or five months ago," Ault declared.[80]

State Secretary Richard Krueger echoed the same sentiments, blaming Local Seattle's incapacitating factionalism on Mills' presence and waxing poetical about the party's bygone days:

The [Sunday] propaganda meetings were a big success from every point of view. They were well attended, in fact, so much so that it was found to be necessary to procure larger quarters....

The attendance at these meetings in this hall soon taxed the full seating capacity. Two hundred extra chairs were rented from a furniture house and crowded into the hall to accommodate the public. The meetings began at 8 pm, and the crowds began to come at 6, constantly in fear not to be fortunate enough to secure a seat.[81]

Despite being outnumbered in the city of Seattle and unable to discipline Mills through Local Seattle, the left wing still held the reins of the State Committee, which continued to mull over the situation into June. At its June 10, 1907 meeting, the State Executive Committee (formerly the Local Quorum) discussed the situation at length and telegraphed a forthcoming action to the membership in a tersely worded report by State Secretary Richard Krueger that he had been instructed "to communicate with all the state committeemen and inform said committeemen of all the facts" regarding the failure of Local Seattle to "deal in a constitutional manner with the charges against Walter Thomas Mills."[82]

At its regularly scheduled June 23, 1907 meeting the State Executive Committee tabulated a poll of the members of the State Committee on the question of Local Seattle and the decision made to proceed with charges against Local Seattle. The State Secretary was instructed to prepare evidence in proper documentary form and to notify Local Seattle to do likewise, with the deadline for submission of its defense given of 30 minutes before the start of the next scheduled meeting of the SEC.[83]

The evidence from both sides was presented at the July 7, 1907 meeting of the SEC, and State Secretary Krueger instructed to present the same to the membership of the party. At this same session, the results of membership voting were announced, thereby electing a new 5 member State Executive Committee and moving state headquarters from Everett, north of Seattle, to Tacoma, about 30 miles (48 km) to the city's south.[84] Despite the change of composition and locale, the left wing still retained majority control over the SEC.

A vote of the State Committee on the Seattle situation was counted and declared official at a meeting of the State Executive Committee held at its new Tacoma headquarters on Sunday, July 21, 1907. By a unanimous vote of the left wing-dominated committee, the charter of Local Seattle was once again revoked, this time for its failure to take action against Walter Thomas Mills.[85] Hermon Titus's right-hand man at the Seattle Socialist, Harry Ault, claimed to speak for "a large number of members of Local Seattle, perhaps even a majority" when he declared:

These comrades are disgusted with the rule or ruin policy of the opportunists, who, though they have been defeated in every state convention and in every referendum in which they have crossed swords with the revolutionists, persist in creating strife and dissension in the party in this state.

The importation of Walter Thomas Mills is merely the culminating act of a band of desperate filibusterers, who, having been foiled in their attempts to control the party, resort to this means to disrupt it and organize it anew upon their plan.[85]

Local Seattle was once again cast adrift by the Socialist Party of Washington, a deep split which deprived the SPW of its largest Local and virtually insured that the matter would be appealed to the national level at the forthcoming convention of 1908. For his part, Mills announced plans to establish a "New Socialist Party" using the members of suspended Local Seattle as a core, with a goal of 1,000 members within a year.[86]

The 1908 National Convention

[edit]In November 1907, with bitter factional battles disrupting the organization in several states, the Socialist Party of America adopted a constitutional amendment which specified that the NEC of the national party should hold a referendum in any state in which two factions requested official recognition upon receipt of a petition of one-third the membership of said state requesting such a vote.[87] No such valid petition was received by the NEC prior to the May 1908 national convention, however, though the predominantly left wing delegates sent to the gathering were challenged, forcing the Washington issue to the convention floor.

As the National Executive Committee had not been able to meet prior to the convention, as planned, the Washington matter was taken up in a special meeting held after the conclusion of the May 11 session of the national conclave, with a report brought to the floor to open business on May 12. Speaking for the NEC, John M. Work of Iowa announced the rejection of the delegate challenge by the moderate faction and their appeal for a referendum vote. Instead, Work diplomatically stated, the NEC recommended "that the national organization offer its good services to the State Committee in Washington against which the protest is made in an effort to bring about unity between the contending sides."[87]

National lecturer George Goebel of New Jersey, who had run afoul of the Washington left wing during two previous speaking tours there, objected to the "beautifully worded program" of the NEC, in which "everybody gets the glad hand." The constructive socialist Goebel presciently warned:

It does not amount to shucks in Washington. I have been to Washington and I tell you that all that this action of the National Executive Committee does is simply to say that a fight is going on. I stand here to tell you, no matter what you do, I stand here to make a prophecy that if this convention adjourns without taking definite action one way or the other in the case of Washington, then inside of a month you will read in the party press of another row in Washington. We have got to deal with the situation. * * *

I believe both sides are absolutely honest. Both sides simply make the mistake of believing that some power above has ordained them masters to save the Socialist rank and file of Washington from being stolen by some crooked capitalist method. That being the case, both sides having made mistakes and properly having come here and stated that they are unable to settle these factional fights within the state, the controversy is for the National Office to adjust. * * *

I call your attention to this: read the state constitution of Washington. They think they have a democratic organization. In that state the State Secretary is not nominated by the rank and file. The State Committee is not nominated by the rank and file; it is nominated by a delegate body, a State Convention... [W]e will settle that; we will have a vote of that rank and file, and then make them stand by that vote of the rank and file. * * *

You can do as you see fit, but you are simply putting off the day for this national action, for the National Executive Committee to step in...[88]

Goebel was answered by the venerable Barney Berlyn of Illinois, one of the only delegates over age 60 and widely respected by all factions as a wise party elder, who declared:

This demand that came to us...of reorganizing every state and making threats to the conflicting factions, where will we stop? Let us pass a general resolution and reorganize, and we will be up in the air. We have got a wise provision of State Autonomy.... In Washington it seems to me they have a fine lot of fish to fry. I do not admire much, either, the way they work it. Some of the people on either side I am perfectly disgusted with, but I feel willing to let that trouble stay in Washington; I do not want any of it in Illinois, and I do not believe anybody wants it settled except in their own state so that they can work harmoniously.[89]

The stage was set for the forthcoming 1909 annual convention of the SPW for what promised to be a decisive battle.

The 1909 Washington State Convention

[edit]The showdown came at the 1909 State Convention of the SPW, held in Everett in July. Both factions campaigned actively and aggressively for delegates.[90] Future Communist Party leader William Z. Foster was then a Socialist Party activist who had moved to Washington from Portland, Oregon during the economic crisis of 1907. He recalled the bitter division that split the state in a memoir published three decades later. Although doubtlessly tendentious in his analysis, left winger William Z. Foster captured something of the flavor of the campaign:

The left wing was supported mostly by lumber workers, city laborers, and semi-proletarian 'stump' farmers. The rights had the backing of the petty businessmen, intellectuals, skilled workers, and better-off farmers. Doubtless the left wing actually polled the majority of votes, but when the convention assembled the right wing had managed to collect a substantial majority of the delegates.

The left wing at once made the charge, with justice, that the rights had utilized their control of the party machinery to pack the convention. Good tactics, however, would have required that the lefts temporarily submit to this manufactured majority and then use the situation to organize the struggle further locally and nationally. But the impulsive 'leftist' Titus was too hasty for that. Under his leadership the left wing refused to participate in the convention, withdrew its delegates, held its own convention, and elected a State Secretary. There were thus two Socialist Parties in Washington.[90]

For the first time in the state's history the moderate faction of the Socialist Party of Washington controlled the organization's annual convention.[91]

Having formed its parallel organization, the left wing attempted to launch a referendum to poll the membership on which State Committee had the support of a majority of the SPW. This proved to be a critical tactical blunder, however, as before the referendum could be completed, the National Executive Committee of the SPA intervened, declaring the balloting unconstitutional and officially recognizing the State Committee headed by the Seattle dentist Dr. E.J. Brown elected by the moderates at the convention from which the left had bolted.[92] Adherents of the left wing dual organization were faced with the daunting task of rejoining the party as individuals under the scrutiny of the moderate-controlled state party apparatus. Many did not.[93]

Hermon Titus and many of his associates thereby abandoned the SPW as no longer worthy of further support. Emphasizing his change of status with respect to the Socialist Party, the name of The Socialist was changed to The Workingman's Paper.[94] Within a year it would be defunct.

The left wing reorganizes itself

[edit]Now outside of the national Socialist Party, the bolting left wing of the Socialist Party of Washington faced the important question of how to proceed. Consideration was made to join the rival Socialist Labor Party, which shared the disdain of the "Reds" for the ameliorative reform and broad political alliance touted by the moderates.[93] Ultimately, however, the domination of the SLP by the personality of Daniel DeLeon and the organization's insistence on establishing dual unions weighed against it.[95]

Instead, a new organization was formed, the Wage Workers Party (WWP). William Z. Foster documented the ideas of this short-lived organization for posterity:

The WWP was sort of a hybrid between the SLP and the IWW. It put in the center of its program its main demand in the fight within the SP. That is, the WWP sought to solve the question of proletarian versus petty bourgeois control of the party by restricting its membership solely to wage workers. It called itself 'a political union,' and its membership provisions specifically excluded 'capitalists, lawyers, preachers, doctors, dentists, detectives, soldiers, factory owners, policemen, superintendents, foremen, professors, and store-keepers.' It barred 'all with power to hire and fire,' but it evaded reference to farmers.'

The program placed great stress upon industrial unionism, which in those times meant the IWW. It opposed the formation of a labor party. Its manifest anti-parliamentarianism was but thinly veiled. It outlined no immediate political demands and showed no conception of the role of the party in fighting for such demands...; the program contented itself with saying vaguely that it would support all struggles of the workers. The whole stress of the party work was placed upon industrial union action and revolutionary agitation and propaganda for the abolition of the capitalist system.[96]

The WWP proved to be stillborn, extant for only a few months — long enough to issue but one issue of its newspaper, The Wage Worker.[96] Few of the leaders of the WWP went back to the Socialist Party, with some, like Harry Ault, going into the mainstream labor movement while others, like Foster and his future son-in-law, Joseph Manley, joining the IWW.[97]

The factional war of the 1910s

[edit]

The departure of Hermon Titus did not end the division within the Socialist Party of Washington, however. It was not long before the battle between Left and Center erupted again in a new form.

Prior to the 1912 Washington state primary election, the state legislature passed a new primary law mandating the election of Precinct Committeemen and the governance of party organizations by those elected officials. The regular Socialist Party of Washington refused to recognize such a mandate from the legislature, contending instead that they were a dues-paying voluntary membership organization under the law, not subject to such regulation. However, a dissident moderate faction based in Seattle and headed by attorney E.J. Brown saw in this new law a means to take control of the state party apparatus. The dissidents used write-in ballots to elect themselves as a dual State Central Committee.[98]

Factional war waged for the next two years, with supporters of Brown's effort expelled from the SPW en masse.

In 1913, L.E. Katterfeld, until recently the head of the Socialist Party's recently terminated national speakers' bureau moved from Chicago to Washington state where he became active in the SPW.

In accordance with the wishes of the National Executive Committee of the SPA, a "Unity Conference" was held on June 18, 1914, a meeting intended to unite the bitter factions of the Washington state party was held. The gathering elected the newcomer Katterfeld as the new State Secretary of the SPW, a post in which he served through 1915.[99]

The SPW during World War I

[edit]A number of activists of the Socialist Party of Washington were embroiled in legal difficulties for their antiwar activity during World War I. On April 16, 1918, Nils Osterberg, secretary of the party's local at Darrington, was arrested for alleged violation of the Espionage Act of 1917 for statements he is said to have on February 1 "unlawfully, willfully, and knowingly" made or conveyed "false reports or false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military...in its war against the Imperial German Government."[100] Osterberg was held in lieu of $20,000 bail in the case.[100]

Osterberg remained in jail for two weeks, unable to raise the substantial bail in his case, before being abruptly released on May 1 when the grand jury to which his case had been presented failed to find sufficient evidence to hold him for trial.[101]

The Farmer-Labor Party and demise of the SPW

[edit]In 1920 the Farmer-Labor Party was organized on a national basis. The organization was particularly strong in Washington state, growing rapidly and very nearly completely absorbing the membership of the Socialist Party of Washington.[102] This burst of energy and activity proved to be short-lived, however, and by the end of 1923 the party had lost its momentum and dissipated.[102]

The Socialist Party of Washington atrophied to the point that it failed to name a ticket for Congressional and State political offices in the 1920 and 1922 campaigns.[102] This weakness was paralleled in the states of Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, which in 1923 were combined as part of a "Northwest Regional" group under the guidance of party veteran Emil Herman.

Electoral performance

[edit]Despite its unending factional acrimony, the Pacific Northwest in general and the Socialist Party of Washington in particular was perhaps the SPA's brightest spot in terms of gathering votes during the first two decades of the 20th century. The state cast 1.9% of its vote for the Debs/Harriman ticket in the Social Democratic Party's 1900 campaign, the second highest percentage total of any state, behind the 2.3% of Massachusetts.[103]

Despite the party falling from 2.98% of the vote in 1904 to 2.82% in 1908 nationwide, the Pacific Northwest managed to outstrip these figures, gaining nearly 5,700 votes in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana combined.[104] Washington was the only state in the entire nation to increase its percentage of Socialist support for Eugene Debs in 1908, with his share of the vote growing from 6.9% in 1904 to 7.7%.[104]

The free speech fights

[edit]

The involvement of the Socialist Party of Washington in the free speech movement of the 1900s seems to have begun naturally, rather than as an intentional provocation of city authorities. In November 1903 the young Organizer of the Pike Street Branch of Local Seattle, Alfred Wagenknecht, announced that he would henceforth be coordinating three "street meetings" featuring teams of soapbox propagandists on street corners prior to each "hall meeting" of the branch — one on the corner of 4th and Pike, another on the corner of 1st and University, and a third on the corner of 2nd and Pike.[105] "The audiences at these street meetings will be invited to attend the hall meetings and in that manner effective work is expected," Wagenknecht noted.[105] Within a short period of time, the Pike Street branch decided to concentrate its efforts on a single street meeting each week, held 2:30 pm each Sunday on the corner of 2nd and Pike.[106]

Matters came to a head in July 1905, when the SPW brought orators Arthur Morrow Lewis and his wife Lena Morrow Lewis to town from San Francisco to address meetings and help build party membership. Arthur Morrow's speeches drew a crowd and he was arrested twice for soapbox speaking on the charge of obstructing the streets, with Local Seattle member M.J. Kennedy and four bystanders were hauled in on the same charge on the third evening. When it became clear that the Socialists planned on making a public issue of the matter, all were ultimately released without trial.[107]

In response, in August 1905 the mayor of Seattle sought to limit public speaking to just two places — a condition rejected by the socialists of Local Seattle as unacceptable as "the streets are for communication as well as transportation and no mayor has any such authority..."[108] The authorities seem to have yielded and no further reports of trouble made their way to the Socialist press.

The second round of the battle between Socialist soapboxers and the forces of "law and order" came late in the summer of 1907 and marked a major escalation. At about 8:30 pm on Tuesday, September 3, blind socialist J.B. Osborne mounted a platform on Pike Street west of First Avenue, just south of the city's new Pike Place Market, which had debuted about two weeks previously.[109] A crowd of about 75 gathered around the street corner orator when he was approached by a uniformed policeman, who told the speaker to apply for a permit at city hall. Osborne discontinued speaking.[109]

Two Seattle Socialists saw Chief of Police Charles "Wappy" Wappenstein the next day and demanded the Socialist Party be granted the same freedom to speak in public allowed the Salvation Army and other organizations. Wappenstein refused, telling the Socialists to "hire a hall."[109]

That night Osborne again mounted the rostrum, and spoke to an audience of 200 for about 20 minutes before a policeman again approached him and told him to quit. Osborne refused and was immediately arrested.[109] His party comrades arrived immediately with money for bail, but regular bail at the jail was refused by orders of the Chief and Osborne was held overnight in the Seattle city jail — a decision which further provoked the Socialists and led to banner headlines in the Seattle Socialist detailing the affair.[109] A protest meeting was scheduled for Sunday night by the party, who saw a fight against the new public speaking rules on Pike Street as a matter of fundamental principle.

Walter Thomas Mills, the nemesis of the "Reds," rather predictably weighed in on the side of order. Mills was quoted in the Republican Seattle Post-Intelligencer as declaring:

No benefit can accrue to Socialism by barking at street corners. I wouldn't give 15 cents for all the street meetings you can hold.... The only way we can go ahead is by determined and persistent canvassing of the individual citizens. We must get persons of intelligence to meet the citizens in their homes and pledge them to cooperation with us....

This scheme of being arrested is the same old farce that was worked here in the past. It has been played elsewhere and nowhere has it brought success....

The men who have been speaking on the streets and hawking their wares have not made any effort to get at the solid, earnest citizens. If we, by thorough canvass reach them, we can build up a party that will mean something and which will stand for something before the city.[110]

Simultaneously in the Eastern part of the state, national lecturer Ida Crouch-Hazlett was arrested in Spokane on a charge of "obstructing the streets" while speaking on a street corner on the evening of Sunday, September 8, 1907. Crouch-Hazlett had just finished speaking from atop a soap box and announced a money collection when, she later recounted, "a policeman with the usual porcine proportions came up and said I would have to clear the sidewalk."[111] The crowd complied for the request for sidewalk clearance by opening a pathway, but this proved insufficient for the officer, who jerked Crouch-Hazlett down from the box.[111] Crouch-Hazlett was arrested while a vast crowd swarmed around her and the arresting officers, screaming "Shame!" and "Cowards!"[111] Crouch-Hazlett was taken to police headquarters and a $25 bond declared, which was quickly offered by a city attorney, who was not himself a Socialist.[111] A crowd reported in the press as 2,000 persons gathered to demand Crouch-Hazlett's release, with the Spokane Fire Department called out to help disburse the gathering. Crouch-Hazlett was released on $25 bail and escorted by a happy throng to her hotel.[112]

Crouch-Hazlett appeared before a judge on Monday amidst a packed courtroom. Declaring that he "didn't want any sensations," the case against Crouch-Hazlett was continued until Thursday and she was roughly escorted from the courtroom by the bailiff.[111] On the scheduled day the judge heard initial arguments and then declared that he wanted to hear the case fully argued and scheduled a trial for Wednesday, September 18, thereby holding Crouch-Hazlett in the city for 10 full days on a charge of blocking the sidewalk.[111]

The Seattle mass arrest

[edit]Back in Seattle the battle continued throughout the fall. Blind orator J.B. Osborne was arrested twice more attempting to speak, running his arrest count to 3, and the Seattle Socialists and their supporters paying out $270 in fines by the first week of October.[113] Further expense was in the offing, as three of Osborne's Police Court cases were headed for appeal by jury trial in County Court.[113] The party telegraphed its next move, publishing in dark type in the pages of The Socialist an appeal for "Volunteers for Jail." "Spring bed Socialism is past in Seattle," the announcement declared: "It means cement floor in jail from now on. Either that or cowardly surrender."[113] Civil disobedience was in the wind.

At 7:30 pm on Monday evening, October 28, 1907, a band of Seattle Socialists braved the pouring rain and headed for the city's new Pike Street Market, bustling with 1500 shoppers.[114] SPW State Chairman John Downie went first, ascending a wooden box in an unused part of the marketplace. A cheer erupted from the crowd which encircled the speaker, and more came running, expecting fireworks. Downie told the crowd of a planned march to the City Council Chamber later that evening — and was promptly arrested.[114] Next came James Lund of Redondo, Washington, who got no further before he, too, was arrested and taken away.[114] Elmer Allison of Local Bangor, A.G. Ball of Portland, Oregon, and Harry Ault and Hulet Wells of Seattle each ascended the box in turn, said a few choice words, and were escorted away by police.[114]

State conventions

[edit]

The Socialist Party of Washington was governed by an annual State Convention. The basis for participation in this body was established by the State Constitution, which originally specified the election of one delegate for every local, and one for every additional 15 members in good standing, or fraction thereof.[115]

1902 Convention: a convention was held in Seattle at state party headquarters on June 29, 1902, the first held under the auspices of the new national SPA, although reckoned as the "third" at the time of the event, taking into account the two previous gatherings of the Social Democratic Party.[116] The gathering featured a heated debated between the radical and moderate wings of the SPW, with the left wing garnering a majority.[117] The convention used a proxy voting system; every member of the SPW was entitled to attend, and delegates could collect mandates from non-attending members and vote in their stead. A total of 244 "votes" were present at the convention, based upon this system.[116] The proxy voting system was eliminated the subsequent year, in favor of required attendance for participation and a limit of one vote to be cast per delegate.[118] the convention adopted a state platform, which again did not include any proposals for ameliorative reform.[119]

The 3rd Annual Washington State Convention was held on July 4, 1903, at Foresters' Hall, located at the corner of Pacific Avenue and 11th Street in Tacoma and was the first held under the terms of the new constitution, which called for 1 delegate for each local plus one additional delegate for every 15 members in good standing or major fraction thereof. The convention was attended by 56 delegates. A motion aimed at repudiating Hermon Titus's Seattle weekly newspaper was tabled by the gathering.[117] Because it was an electoral off-year, no nominations were made by the party for political office. the convention placed a limitation on the compensation of the SPW for all regular organizers and speakers, capping their compensation at $3 per day with an additional $2 for expenses.[117] A series of proposed amendments to the state constitution were made, including those prohibiting members from accepting appointments to political office from other than the Socialist Party, requiring one year's previous membership for party candidates for public office, and requiring the expulsion of "any member advocating fusion with any party or faction not representing revolutionary Socialism."[117] Seattle was reestablished as party headquarters and a new Local Quorum elected. Left-winger George Boomer of Prosser was renominated for National Committee member, with moderate William McDevitt selected to run against him.[117]

The 5th Annual Washington State Convention was held July 2–3, 1905 in Seattle. The gathering was easily controlled by the left wing faction, which removed Central Branch moderates M. Parsons and George W. Scott from the Seattle-based Local Quorum, which acted as an Executive Committee, and declared Irene Smith's contested election to the National Committee to be void. Owing to the resignation of D. Burgess, who moved to Ohio, this left both of the states seats on the National Committee open for vote, with 6 nominations made for the two positions. Constitutional restructuring was proposed which called for a State Committee of 15, with no 2 of these from the same Local, and an expanded Local Quorum of 5, including left winger Alfred Wagenknecht from Seattle.[120] Following the convention, the outgoing State Committee, populated with members from the moderate faction, launched a last-ditch effort at the removal of State Secretary E.E. Martin, with a referendum for his removal launched by J.W. Smith of Tacoma, husband of embattled National Committee member Irene Smith. This was short-circuited by the accelerated removal of the Parsons and Scott by the rest of the State Committee in August, followed later that month by the formal election of a new Local Quorum for the state which included left wingers Wagenknecht and his brother-in-law Elmer Allison, along with three others, only one of who owed factional allegiance to the moderates.

The 7th Annual Washington State Convention was held May 4–5, 1907 in Seattle. The first test of strength came shortly after the 10:10 am opening, when moderate T.E. Latimer and left winger David Burgess stood off in an election for temporary chairman. Latimer was narrowly defeated by Burgess by a count of 25 to 23 — the best show of strength for the moderates of the convention.[121] The Credentials Committee again brought up the case of Walter Thomas Mills, with the majority reporting that Mills should be denied his seat because he was under charges. This was followed by a resolution by Seattle left wing delegate J.A. McCorkle that the convention officially note that Mills stood under charges preferred by the Socialist Party of Canada for supporting candidates opposed to that party in the recent British Columbia provincial elections. A massive storm of protest erupted, with heated debate occupying the entire afternoon session. In the evening session the question was finally called and the convention voted that Mills was indeed under charges by a vote of 47 to 27.[121] Mills recorded a formal protest and an alternate delegate was seated in his stead.[121] The convention reaffirmed the SPW's strict anti-fusion policies and moved state headquarters from Everett to Tacoma. A new State Executive Committee was elected by referendum vote of the membership following completion of the convention.