Solution of triangles

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

Solution of triangles (Latin: solutio triangulorum) is the main trigonometric problem of finding the characteristics of a triangle (angles and lengths of sides), when some of these are known. The triangle can be located on a plane or on a sphere. Applications requiring triangle solutions include geodesy, astronomy, construction, and navigation.

Solving plane triangles

[edit]

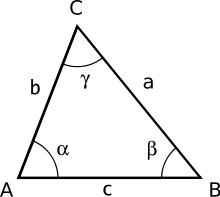

A general form triangle has six main characteristics (see picture): three linear (side lengths a, b, c) and three angular (α, β, γ). The classical plane trigonometry problem is to specify three of the six characteristics and determine the other three. A triangle can be uniquely determined in this sense when given any of the following:[1][2]

- Three sides (SSS)

- Two sides and the included angle (SAS, side-angle-side)

- Two sides and an angle not included between them (SSA), if the side length adjacent to the angle is shorter than the other side length.

- A side and the two angles adjacent to it (ASA)

- A side, the angle opposite to it and an angle adjacent to it (AAS).

For all cases in the plane, at least one of the side lengths must be specified. If only the angles are given, the side lengths cannot be determined, because any similar triangle is a solution.

Trigonomic relations

[edit]

The standard method of solving the problem is to use fundamental relations.

There are other (sometimes practically useful) universal relations: the law of cotangents and Mollweide's formula.

Notes

[edit]- To find an unknown angle, the law of cosines is safer than the law of sines. The reason is that the value of sine for the angle of the triangle does not uniquely determine this angle. For example, if sin β = 0.5, the angle β can equal either 30° or 150°. Using the law of cosines avoids this problem: within the interval from 0° to 180° the cosine value unambiguously determines its angle. On the other hand, if the angle is small (or close to 180°), then it is more robust numerically to determine it from its sine than its cosine because the arc-cosine function has a divergent derivative at 1 (or −1).

- We assume that the relative position of specified characteristics is known. If not, the mirror reflection of the triangle will also be a solution. For example, three side lengths uniquely define either a triangle or its reflection.

Three sides given (SSS)

[edit]

Let three side lengths a, b, c be specified. To find the angles α, β, the law of cosines can be used:[3]

Then angle γ = 180° − α − β.

Some sources recommend to find angle β from the law of sines but (as Note 1 above states) there is a risk of confusing an acute angle value with an obtuse one.

Another method of calculating the angles from known sides is to apply the law of cotangents.

Area using Heron's formula: where

Heron's formula without using the semiperimeter:

Two sides and the included angle given (SAS)

[edit]

Here the lengths of sides a, b and the angle γ between these sides are known. The third side can be determined from the law of cosines:[4] Now we use law of cosines to find the second angle: Finally, β = 180° − α − γ.

Two sides and non-included angle given (SSA)

[edit]

This case is not solvable in all cases; a solution is guaranteed to be unique only if the side length adjacent to the angle is shorter than the other side length. Assume that two sides b, c and the angle β are known. The equation for the angle γ can be implied from the law of sines:[5] We denote further D = c/b sin β (the equation's right side). There are four possible cases:

- If D > 1, no such triangle exists because the side b does not reach line BC. For the same reason a solution does not exist if the angle β ≥ 90° and b ≤ c.

- If D = 1, a unique solution exists: γ = 90°, i.e., the triangle is right-angled.

- If D < 1 two alternatives are possible.

- If b ≥ c, then β ≥ γ (the larger side corresponds to a larger angle). Since no triangle can have two obtuse angles, γ is an acute angle and the solution γ = arcsin D is unique.

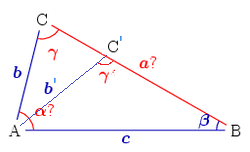

- If b < c, the angle γ may be acute: γ = arcsin D or obtuse: γ′ = 180° − γ. The figure on right shows the point C, the side b and the angle γ as the first solution, and the point C′, side b′ and the angle γ′ as the second solution.

Once γ is obtained, the third angle α = 180° − β − γ.

The third side can then be found from the law of sines:

or from the law of cosines:

A side and two adjacent angles given (ASA)

[edit]

The known characteristics are the side c and the angles α, β. The third angle γ = 180° − α − β.

Two unknown sides can be calculated from the law of sines:[6]

A side, one adjacent angle and the opposite angle given (AAS)

[edit]The procedure for solving an AAS triangle is same as that for an ASA triangle: First, find the third angle by using the angle sum property of a triangle, then find the other two sides using the law of sines.

Other given lengths

[edit]In many cases, triangles can be solved given three pieces of information some of which are the lengths of the triangle's medians, altitudes, or angle bisectors. Posamentier and Lehmann[7] list the results for the question of solvability using no higher than square roots (i.e., constructibility) for each of the 95 distinct cases; 63 of these are constructible.

Solving spherical triangles

[edit]

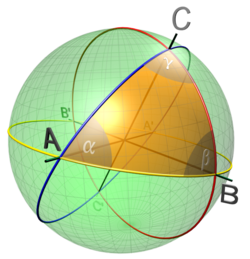

The general spherical triangle is fully determined by three of its six characteristics (3 sides and 3 angles). The lengths of the sides a, b, c of a spherical triangle are their central angles, measured in angular units rather than linear units. (On a unit sphere, the angle (in radians) and length around the sphere are numerically the same. On other spheres, the angle (in radians) is equal to the length around the sphere divided by the radius.)

Spherical geometry differs from planar Euclidean geometry, so the solution of spherical triangles is built on different rules. For example, the sum of the three angles α + β + γ depends on the size of the triangle. In addition, similar triangles cannot be unequal, so the problem of constructing a triangle with specified three angles has a unique solution. The basic relations used to solve a problem are similar to those of the planar case: see Spherical law of cosines and Spherical law of sines.

Among other relationships that may be useful are the half-side formula and Napier's analogies:[8]

Three sides given (spherical SSS)

[edit]Known: the sides a, b, c (in angular units). The triangle's angles are computed using the spherical law of cosines:

Two sides and the included angle given (spherical SAS)

[edit]Known: the sides a, b and the angle γ between them. The side c can be found from the spherical law of cosines:

The angles α, β can be calculated as above, or by using Napier's analogies:

This problem arises in the navigation problem of finding the great circle between two points on the earth specified by their latitude and longitude; in this application, it is important to use formulas which are not susceptible to round-off errors. For this purpose, the following formulas (which may be derived using vector algebra) can be used: where the signs of the numerators and denominators in these expressions should be used to determine the quadrant of the arctangent.

Two sides and non-included angle given (spherical SSA)

[edit]This problem is not solvable in all cases; a solution is guaranteed to be unique only if the side length adjacent to the angle is shorter than the other side length. Known: the sides b, c and the angle β not between them. A solution exists if the following condition holds: The angle γ can be found from the spherical law of sines: As for the plane case, if b < c then there are two solutions: γ and 180° - γ.

We can find other characteristics by using Napier's analogies:

A side and two adjacent angles given (spherical ASA)

[edit]Known: the side c and the angles α, β. First we determine the angle γ using the spherical law of cosines:

We can find the two unknown sides from the spherical law of cosines (using the calculated angle γ):

or by using Napier's analogies:

A side, one adjacent angle and the opposite angle given (spherical AAS)

[edit]Known: the side a and the angles α, β. The side b can be found from the spherical law of sines:

If the angle for the side a is acute and α > β, another solution exists:

We can find other characteristics by using Napier's analogies:

Three angles given (spherical AAA)

[edit]Known: the angles α, β, γ. From the spherical law of cosines we infer:

Solving right-angled spherical triangles

[edit]The above algorithms become much simpler if one of the angles of a triangle (for example, the angle C) is the right angle. Such a spherical triangle is fully defined by its two elements, and the other three can be calculated using Napier's Pentagon or the following relations.

- (from the spherical law of sines)

- (from the spherical law of cosines)

- (also from the spherical law of cosines)

Some applications

[edit]Triangulation

[edit]

If one wants to measure the distance d from shore to a remote ship via triangulation, one marks on the shore two points with known distance l between them (the baseline). Let α, β be the angles between the baseline and the direction to the ship.

From the formulae above (ASA case, assuming planar geometry) one can compute the distance as the triangle height:

For the spherical case, one can first compute the length of side from the point at α to the ship (i.e. the side opposite to β) via the ASA formula and insert this into the AAS formula for the right subtriangle that contains the angle α and the sides b and d: (The planar formula is actually the first term of the Taylor expansion of d of the spherical solution in powers of ℓ.)

This method is used in cabotage. The angles α, β are defined by observation of familiar landmarks from the ship.

As another example, if one wants to measure the height h of a mountain or a high building, the angles α, β from two ground points to the top are specified. Let ℓ be the distance between these points. From the same ASA case formulas we obtain:

The distance between two points on the globe

[edit]

To calculate the distance between two points on the globe,

- Point A: latitude λA, longitude LA, and

- Point B: latitude λB, longitude LB

we consider the spherical triangle ABC, where C is the North Pole. Some characteristics are: If two sides and the included angle given, we obtain from the formulas Here R is the Earth's radius.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Solving Triangles". Maths is Fun. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Solving Triangles". web.horacemann.org. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Solving SSS Triangles". Maths is Fun. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Solving SAS Triangles". Maths is Fun. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Solving SSA Triangles". Maths is Fun. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ "Solving ASA Triangles". Maths is Fun. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Alfred S. Posamentier and Ingmar Lehmann, The Secrets of Triangles, Prometheus Books, 2012: pp. 201–203.

- ^ Napier's Analogies at MathWorld

- Euclid (1956) [1925]. Sir Thomas Heath (ed.). The Thirteen Books of the Elements. Volume I. Translated with introduction and commentary. Dover. ISBN 0-486-60088-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit]- Trigonometric Delights, by Eli Maor, Princeton University Press, 1998. Ebook version, in PDF format, full text presented.

- Trigonometry by Alfred Monroe Kenyon and Louis Ingold, The Macmillan Company, 1914. In images, full text presented. Google book.

- Spherical trigonometry on Math World.

- Intro to Spherical Trig. Includes discussion of The Napier circle and Napier's rules

- Spherical Trigonometry — for the use of colleges and schools by I. Todhunter, M.A., F.R.S. Historical Math Monograph posted by Cornell University Library.

- Triangulator – Triangle solver. Solve any plane triangle problem with the minimum of input data. Drawing of the solved triangle.

- TriSph – Free software to solve the spherical triangles, configurable to different practical applications and configured for gnomonic.

- Spherical Triangle Calculator – Solves spherical triangles.

- TrianCal – Triangles solver by Jesus S.

KSF

KSF

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\alpha &=\arccos {\frac {b^{2}+c^{2}-a^{2}}{2bc}}\\[4pt]\beta &=\arccos {\frac {a^{2}+c^{2}-b^{2}}{2ac}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/468caceefca9cadbcccf4071a44d9c3107dd5b33)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=c\ {\frac {\sin \alpha }{\sin \gamma }}=c\ {\frac {\sin \alpha }{\sin(\alpha +\beta )}}\\[4pt]b&=c\ {\frac {\sin \beta }{\sin \gamma }}=c\ {\frac {\sin \beta }{\sin(\alpha +\beta )}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5a1c29dcb0becc667ec27c3b326704a8f7311fb1)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\alpha &=\arccos {\frac {\cos a-\cos b\ \cos c}{\sin b\ \sin c}},\\[4pt]\beta &=\arccos {\frac {\cos b-\cos c\ \cos a}{\sin c\ \sin a}},\\[4pt]\gamma &=\arccos {\frac {\cos c-\cos a\ \cos b}{\sin a\ \sin b}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f8146ca926b00d06a044d271ab5c7df1a35ac820)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\alpha &=\arctan \ {\frac {2\sin a}{\tan {\frac {1}{2}}\gamma \,\sin(b+a)+\cot {\frac {1}{2}}\gamma \,\sin(b-a)}},\\[4pt]\beta &=\arctan \ {\frac {2\sin b}{\tan {\frac {1}{2}}\gamma \,\sin(a+b)+\cot {\frac {1}{2}}\gamma \,\sin(a-b)}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9e2b78e0b7ef699aa8af5da266bb72622878b1bb)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}c&=\arctan {\frac {\sqrt {(\sin a\cos b-\cos a\sin b\cos \gamma )^{2}+(\sin b\sin \gamma )^{2}}}{\cos a\cos b+\sin a\sin b\cos \gamma }},\\[4pt]\alpha &=\arctan {\frac {\sin a\sin \gamma }{\sin b\cos a-\cos b\sin a\cos \gamma }},\\[4pt]\beta &=\arctan {\frac {\sin b\sin \gamma }{\sin a\cos b-\cos a\sin b\cos \gamma }},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/676ea5979c99d815741d6c46f6521df506b7ab6c)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=2\arctan \left[\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(b-c)\ {\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(\beta +\gamma )}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(\beta -\gamma )}}\right],\\[4pt]\alpha &=2\operatorname {arccot} \left[\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(\beta -\gamma )\ {\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(b+c)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(b-c)}}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1fcf728f4773fd11e17d9277dda271af8f43fcf0)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=\arccos {\frac {\cos \alpha +\cos \beta \cos \gamma }{\sin \beta \sin \gamma }},\\[4pt]b&=\arccos {\frac {\cos \beta +\cos \alpha \cos \gamma }{\sin \alpha \sin \gamma }},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e470edadf64a525545cbc0e7d2bb7d4d372a5dc8)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=\arctan {\frac {2\sin \alpha }{\cot {\frac {1}{2}}c\,\sin(\beta +\alpha )+\tan {\frac {1}{2}}c\,\sin(\beta -\alpha )}},\\[4pt]b&=\arctan {\frac {2\sin \beta }{\cot {\frac {1}{2}}c\,\sin(\alpha +\beta )+\tan {\frac {1}{2}}c\,\sin(\alpha -\beta )}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/27f2427d28ff2add6a071ea143c932158667a7da)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}c&=2\arctan \left[\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)\ {\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(\alpha +\beta )}{\sin {\frac {1}{2}}(\alpha -\beta )}}\right],\\[4pt]\gamma &=2\operatorname {arccot} \left[\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(\alpha -\beta )\ {\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)}{\sin {\frac {1}{2}}(a-b)}}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/235ec9d0e90a8baeae97e513ccb5448b054cc0e5)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=\arccos {\frac {\cos \alpha +\cos \beta \cos \gamma }{\sin \beta \sin \gamma }},\\[4pt]b&=\arccos {\frac {\cos \beta +\cos \gamma \cos \alpha }{\sin \gamma \sin \alpha }},\\[4pt]c&=\arccos {\frac {\cos \gamma +\cos \alpha \cos \beta }{\sin \alpha \sin \beta }}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6c8492b87f5c7df61063d1ef43b69d3737457f74)

![{\displaystyle {\overline {AB}}=R\arccos \!{\Bigr [}\sin \lambda _{A}\sin \lambda _{B}+\cos \lambda _{A}\cos \lambda _{B}\cos(L_{A}-L_{B}){\Bigr ]}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/76ad6de4332b7972068af1b25934e5e3b1b682cd)