Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

| Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Queen consort of Denmark and Norway | |

| Tenure | 20 July 1572 – 4 April 1588 |

| Born | 4 September 1557 Wismar |

| Died | 4 October 1631 (aged 74) Nykøbing Castle, Falster |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Mecklenburg-Schwerin |

| Father | Ulrich III of Mecklenburg-Güstrow |

| Mother | Elizabeth of Denmark |

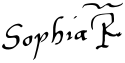

| Signature |  |

Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow (Sophia; 4 September 1557 – 4 October 1631) was Queen of Denmark and Norway by marriage to Frederick II of Denmark. She was the mother of King Christian IV of Denmark and Anne of Denmark. She was Regent of Schleswig and Holstein from 1590 to 1594.[1]

The only child of Ulrich III of Mecklenburg and Elizabeth of Denmark, Sophie married her cousin, Frederick II of Denmark, in 1572, and their marriage was remarkably happy.[2][3] She had little political influence during their marriage, although she maintained her own court and exercised a degree of autonomy over patronages.[4] Sophie developed an interest in astrology, chemistry, alchemy and iatrochemistry,[5] supporting and visiting Tycho Brahe on Ven in 1586 and later.[4] She has later been described as a woman "of great intellectual capacity, noted especially as a patroness of scientists".[6] She became widowed at the age of 31 and in the first few years after Frederick's death, Sophie vigorously endeavoured to consolidate her position of power. However, lacking domestic allies and faced with a power-conscious Danish nobility, this was only partially successful; while she was recognized as regent of Schleswig and Holstein, her efforts to lead the regency council of her underage son came into direct conflict with the Danish Council of the Realm and ultimately proved unsuccessful. In 1594, she retreated to her dower estate, comprising the islands of Lolland and Falster. Despite this setback, Sophie's influence did not diminish throughout her widowhood; on the contrary, she was unwilling to be sidelined from political affairs,[7] and she greatly strengthened her status through enormous and ever-expanding monetary leverage.[8]

Through the skilful management of her vast widowed estate, she amassed an enormous fortune, becoming the richest woman in Northern Europe[9] and the second wealthiest individual in Europe after Maximillian I of Bavaria.[10] From the outset, Sophie displayed exceptional enterprise and determination, implementing wide-scale agrarian reforms to increase the yield and revenue of her estate. Frequently disbursing funds from her "inexhaustible coffers", Sophie financially supported her son, as well as the Council of the Realm, and thereby effectively the entire Danish-Norwegian state.[11][12][13] She maintained a large lending business, earning interest, and extending loans to, among others her son Christian IV, her son-in-law King James VI & I, her grandson Duke Frederick Ulrich of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and several other principalities of the Holy Roman Empire.[8] When she died in 1631, James Howell, secretary to the English Ambassador in Denmark, remarked that she was the "richest Queen in Christendom".[14]

Queen Sophie exerted significant political influence both domestically and internationally during her widowhood.[15] She strengthened the Protestant alliances of Denmark through the arrangement of influential marriages for her daughters, often contributing substantial funds for the dowry and jewellery herself. She also conducted extensive correspondence with rulers and nobles across northern Europe, and through her strategic economic dealings, she "[financed] diplomacy and war", as described by historian Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks.[16] Sophie played a crucial role in shaping the foreign relations of Denmark, notably during the Thirty Years' War, influencing peace negotiations and ultimately contributing to the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629.[17][18]

Some historians, especially earlier ones, have either disregarded Sophie or dismissed her as power-hungry and rapacious.[19] However, 19th-century writers including Ellen Jørgensen considered her a woman of "unparalleled skill" and "indomitable resourcefulness".[20] Recent reassessments recognize her remarkable entrepreneurship as a dowager, and in particular her ability to entrench herself as a pervasive power in the political landscape of late Reformation Denmark and Europe.[8][21]

Early life

[edit]Born in Wismar, she was the daughter of Duke Ulrich III of Mecklenburg-Güstrow and Princess Elizabeth of Denmark (a daughter of Frederick I and Sophie of Pomerania). Through her father, a grandson of Elizabeth of Denmark, she descended from King John of Denmark, the brother of Frederick I. Like Ulrich, she had a great love of knowledge. Later, she would be known as one of the most learned Queens of the time.

Queen

[edit]

At the age of fourteen Sophie, on 20 July 1572, married Frederick II of Denmark in Copenhagen; he was thirty-eight. She was crowned the following day.[22] They were first half-cousins, through their grandfather, Frederick I, King of Denmark and Norway. They met at Nykøbing Castle, when it had been arranged for the king to meet with Margaret of Pomerania, daughter of Philip I of Pomerania. She was brought to Denmark by Sophie's parents, who decided to also bring their own daughter.[23] Sophie found favour with the king, who betrothed himself to her, and married her six months later.[24] King Frederick had been in love with the noblewoman Anne Corfitzdatter Hardenberg for many years, but was unable to marry her due to her being a noblewoman, not a princess, the opposition of the Danish Privy Council as well as eventually Anne herself.[23]

Despite the age difference between Sophie and Frederick, the marriage was a happy one. Queen Sophie was a loving mother, nursing her children personally during their illnesses. When Frederick was sick with malaria in 1575, she personally nursed him and wrote many worried letters to her father about his progress.[25][23] King Frederick was well known for being fond of drinking and hunting,[23] but he was a loving spouse to Sophie, writing of her with great fondness in his personal diary (where he kept careful track of where she and their children were in the country[26]) and there is no evidence of extramarital affairs on the part of either spouse.[27] Their marriage is described as having been harmonious.[27][23] All of their children were sent to live with her parents in Mecklenburg for the first years of their lives, with the possible exception of the last son, Hans, as it was the belief at the time that the parents would indulge their children too much.[23][27] She showed a keen interest in science and visited the astronomer Tycho Brahe.[27] She was also interested in the old songs of folklore.[27]

Matchmaker

[edit]Around the time of Frederick's death, Sophie's most important function was as a matchmaker for her children. Her daughter, Anne of Denmark, married James VI of Scotland and became queen consort in 1589. She arranged the marriage against the will of the council. When James VI came to Denmark, she gave him a present of 10,000 dalers.[28] She was also deeply involved in the negotiations that led to the wedding of Princess Elizabeth to Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. She oversaw the levying of 150,000 dalers for the two weddings and other expenses, and spent herself 50,000 on jewellery.[29]

In 1596, she arranged the marriage of her daughter Princess Augusta to John Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, which improved Denmark's connections to the north German Lutheran states. Finally, in 1602, she negotiated the marriage of Hedwig to Christian II, Elector of Saxony. She also played a key role in finding appropriate spouses for her younger sons.[29] She was the main negotiator in the marriage arrangements between her son Christian, heir to the throne, and Princess Anne Catherine of Brandenburg, whom Sophie called a "pure pearl".[30]

Widowhood and queen-dowager

[edit]

Regency and conflicts with the Council of the Realm

[edit]Queen Sophie had no political power during the lifetime of her spouse.[27] When her underage son Christian IV became king in 1588, she was given no place in the regency council in Denmark itself.[27] From 1590, however, she acted as regent for the duchies of Schleswig-Holstein for her son.[27]

She organized a grand funeral for her spouse, arranged for the dowries for her daughters and for her own allowance, all independently and against the will of the council.[27] She engaged in a power struggle with the regents of Denmark and with the Council of State, which had Christian declared of age in 1593.[27] She wished the duchies to be divided between her younger sons, which caused a conflict.[27] Sophie only gave up her position the following year, 1594. In response, Sophie began securing the resources she would need to remain an influential figure within Denmark.

Landowner and successful entrepreneur

[edit]

As dowager-queen, Sophie was entitled to 'Dowager-pension' (Danish: Livgeding, lit. 'support of life') as well as the castles that comprised her morning gift. These vast estates included Denmark's fourth-largest island Lolland, and the neighbouring island Falster, on which the castle of Nykøbing was situated, which she also received.[15] She also received Aalholm Castle, Halsted Priory, Vennerslund, Ravnsborg, and the fiefs belonging thereto. She succeeded in obtaining 30,000 rigsdaler from her late husband's liquid assets, as well as an annual income of 8,000 rigsdaler from the Sound Dues.[31] Over a number of years, her crown property on Lolland and Falster was expanded, with large properties being transferred to the widow's estate, including Corselitze and Skørringe, whose holdings on Falster totalled over 100 farm estates.[32]

During her long widowhoow, Sophie mainly devoted herself to managing her estates, where she was effectively an independent ruler. She protected the residents of her dowerlands and engaged in large-scale trade and in money-lending.[27] She took a keen interest in new agricultural technology, converted her land to large-scale farming, sold grain and cattle to northern Germany through her large established network in the principalities, built mills and was especially interested in cattle breeding, which was an important source of income during this period.[33] The still existing Queen's Warehouse in Nakskov was constructed for her in 1589–1591.[34]

The Dowager Queen Sophie managed her estates in Lolland-Falster so well, that her son could borrow money from her on several occasions for his wars.[27] She helped to fund her son Christian IV's military campaign against Sweden in 1611, the Kalmar War, and his entry into the Thirty Years War in 1615. Likewise, she also assisted her son with a loan in 1605 of 140,000 Danish rigsdaler, whereupon Christian launched a series of expeditions to Greenland. In 1614, Christian IV took out another loan of 210,000 rigsdaler from his mother.[11] In 1621, the Danish Council of the Realm obtained two loans of 100,000 and 280,000 rigsdaler respectively from the Dowager Queen, to cover the state's deficit.[35][11] The majority of the Dowager Queen's loans to her son were never repaid.[11]

In 1620–21, Dowager Queen Sophie was the main contributor of a loan of 300,000 rigsdaler from the Danish state under Christian IV, to England under her son-in-law James VI and I.[11] The interest rate was the "extremely favourable" 6%.[36] In addition to her liquid assets amounting to millions of guilders, she also had extensive properties in the north of the Holy Roman Empire, pledged by princely creditors. The queen inspected these estates during her numerous journeys.[37]

Political influence as widow

[edit]

Because of her great wealth, Dowager Queen Sophie was able to exercise considerable influence on both Danish domestic affairs and the international politics of Northern Europe during the reign of her son, Christian IV (reigned 1596–1648). During a period from the death of her husband in 1588 until her death forty-three years later, she was active in the political life of Denmark.[15] The queen dowager maintained a constant awareness of the current political developments in Europe and in the empire, through intensive correspondence with Protestant princes and her Mecklenburg relatives.[37]

Domestically, Sophie influenced and supported the realm through continuous financial loans. Correspondence also shows that Sophie engaged in financial discussions with her son about the levying of taxes.[38] Interestingly, the Danish Privy Council also granted her the concession that she was allowed to receive ambassadors and thus essentially conduct diplomacy on behalf of Denmark.[39] Her extensive territories in southern Denmark also included the jurisdiction over a number of birks (judicial districts), where she held executive powers to appoint judges (Danish: birkedommer; viz. judge of a Danish District Court).[40]

The Dowager Queen had notable political influence internationally as a consequence of her loans to several principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, whereby she "[financed] diplomacy and war", as described by historian Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks.[16] During the Thirty Years' War, she lent money to several German Protestant princes, and among her creditors was her grandson Duke Frederick Ulrich of Brunswick-Lüneburg, who owed her 300,000 Danish rigsdaler,[38] as well as her son-in-law John Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, to whom she also lent 300,000 rigsdaler.[41] She also conducted financial dealings with the leader of the Catholic forces, Count Tilly, with whom she wanted to form a joint creditors' front.[42]

In 1620, her grandson-in-law, Frederick V of the Palatinate, husband to her granddaughter Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, was deposed. The couple soon fled Prague and settled in The Hague, and during this period, Elizabeth and Sophie maintained frequent correspondence. In 1621, Queen Dowager Sophie engaged her connections in Hamburg and with "a mootherlie Caire", as described by Sir Robert Antrusther, she provided £20.000 (equivalent to approximately £4,500,000 today[43]) to support the couple's immediate needs and "to serve the present want of heere highnes", as Sophie wrote.[44]

During the latter stages of the Danish participation in the Thirty Years' War, Dowager Queen Sophie played a diplomatic role by engaging in extensive correspondence with various parties involved. She corresponded with, among others, numerous electors of the Holy Roman Empire, including John George I, Elector of Saxony, Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, Ferdinand of Bavaria, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, Philipp Christoph von Sötem, Archbishop-Elector of Trier and Georg Friedrich von Greiffenklau, Archbishop-Elector of Mainz, through which she established numerous declarations from German princes for their assistance in the promotion and intervention on behalf of peace, and to send delegates to participate in peace negotiations in Lübeck, which in May 1629 led to the Treaty of Lübeck, ending the Danish intervention in the Thirty Years' War.[45]

She also corresponded with Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, notably concerning her displeasure at the inadequate protection of her financial interests during the Thirty Years' War, where imperial supreme commander, Albrecht von Wallenstein, had seized the Mecklenburg territories of her debtors, and refused to pay interest or installments on the debt.[46] Wallenstein had deposed her cousins and loanees, John Albert II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, and Adolphus Frederick I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1628, and Sophie provided “active support”, interceding on behalf of the dukes, and became deeply involved in the situation. She repeatedly pleaded the case before the emperor, and by exerting her influence with her son, Christian IV, she was able to secure them temporary aid.[47] Personally, she deferred interest and provided additional loans to the dukes, in addition to receiving Adolphus Frederick's wife and children at Nykøbing Castle, as the situation became unsafe in Schwerin.[48] At the end of 1629, lively but inconclusive negotiations with the Imperial Court had taken place on the subject. Emperor Ferdinand II acquiesced to Sophie's requests and wrote several times to Wallenstein, but with no favourable outcome for the Dowager Queen.[46]

Later life

[edit]She often visited Mecklenburg, and attended the wedding of her daughter, Princess Hedwig, to Christian II, Elector of Saxony, in Dresden in 1602. She travelled with her family to Bützow in March 1624, to attend the funeral of her son, Ulrik, Prince-Bishop of Schwerin. In 1603 she became involved in an inheritance dispute with her uncle, which remained unsolved at his death in 1610.[27] In 1608, she managed to soften the punishment of Rigborg Brockenhuus, and in 1628, she was one of the influential people who prevented her son from having her grandson's lover, Anne Lykke, accused of witchcraft.[27]

Death, fortune and inheritance disputes

[edit]

At the end of September 1631, Christian IV arrived in Nykøbing. The Queen Dowager was seriously ill and was attended by the royal physician, Dr. Henning Arsenius. On 3 October the keys to the castle were handed over to the king's sister, Duchess Augusta, “because there is nothing more to hope for now than certain death”. Sophie died the following day.[50]

When Sophie died in 1631 at Nykøbing Falster, at the age of seventy-four, she was the richest woman in Europe.[42] She left three children, Christian, Hedwig and Augusta, four had died before her. All three attended the funeral, said to be conducted with great splendour. Her body was brought from Nykøbing via Vordingborg to Copenhagen, and a solemn funeral service took place in the Church of Our Lady on 13 November 1631. The next day the body was taken to Roskilde Cathedral, and laid to rest in the Chapel of the Magi, beside her long-deceased husband.[51] The coffin with the queen's remains has since been transferred to the crypt underneath the actual chapel.[52]

Fortune and inheritance

[edit]Sophie left an absolutely enormous inheritance, which was valued at well over 5.5 million Danish rigsdaler,[53][42] an amount difficult to convert to the present day, but at the time it was equivalent to approximately 10 times the annual government revenue of the Danish-Norwegian state, compared to the period 1620–1622.[54] In 1775, historian Johann Heinrich Schlegel estimated that the liquid assets of her fortune in 1631, was equivalent to 27 tons of gold in 1775.[55] Corrected for inflation, her combined fortune would thus be equivalent to several billion pounds.

The Dowager Queen had left no actual testament, but in a letter to her son King Christian, she had declared that her three living children should receive a sizeable pre-legacy, a non-distributable portion (Danish: forlods), the rest to be divided according to law,[51] with the exception of a few bequests, including to Sorø Academy.[56] The prelegacy consisted of all silverware in the Queen's chambers at Nykøbing Castle, all royal gold in her possession and her personal jewellery, clothes and linen, which were given to her daughters. The gold was divided equally between the king and his two sisters. This pre-distribution took place on 4 December 1631 at Nykøbing, a month after her funeral.[57]

After the distribution of the prelegacy, the main estate itself was to be divided. The assets consisted of outstanding capital, interest, considerable cash, jewellery, coins and sizeable collateralized territories in Mecklenburg – her dowerlands of Lolland and Falster reverted to the Crown. Her jewellery and valuables alone are believed to be worth over a million rigsdaler, and were stored in 45 large wooden chests.[58] Actively engaged in money lending to the end, a considerable part of Sophie's assets consisted of her outstanding capital. The largest borrower was her son, Christian IV, who in 1631 owed his mother more than a million Danish rigsdaler. In addition, other family members such as her grandsons, Frederick III, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp owed almost 600,000 rigsdaler, Frederick Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg over 300,000 rigsdaler, and her cousins, John Albert II, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, and Adolphus Frederick I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, each owed 220,000 rigsdaler and almost 140,000 rigsdaler, respectively. The city of Rostock itself also had an unpaid debt of 20,000 rigsdaler.[59]

Furthermore, there was considerable interest to be recovered from her European lending business. In total, this amounted to well over 215,000 rigsdaler, including interest from Albrecht von Wallenstein, who owed the Queen 63,000 rigsdaler for his time as mortgage holder of the Duchy of Mecklenburg.[60]

Claims and disputes

[edit]Upon Sophie's death, a dispute quickly arose over her inheritance.[61] As news of Sophie's demise spread across Northern Europe, several German principalities began dispatching envoys to Copenhagen to negotiate and settle inheritance claims.[50] By letter of 31 December 1631, Christian IV summoned all heirs for the division of the main estate, and scheduled this for the following April (in 1632) at Nykøbing Castle, Falster. Altogether, the inheritance settlement was completed by June 1632, although not without controversy.[62]

Some initial disputes even required imperial intervention. During the process of recording all the valuables Sophie left behind, it became known that her daughter, Duchess Augusta, retained one of the two original handwritten inventories of the estate, from when she was handed the keys to Nykøbing Castle. Since amicable means of obtaining the inventory from the Duchess failed, an imperial mandate from Ferdinand II, was issued to her, dated 5 November 1635, in Vienna.[63]

Discussions on the distribution of the estate primarily concerned the extent of inheritance rights for the grandchildren of Sophie, more specifically the offspring of Sophie's two predeceased daughters Anne and Elizabeth. Her grandson, Charles I of England, ordered the English court to enter into mourning,[64] and immediately deployed an ambassador extraordinaire, Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester, to the Danish court to offer condolences, and claim part of the inheritance.[65] Sophie's granddaughter, Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, also sought a portion of the inheritance. Unlike her brother Charles, she had not inherited from her mother, Anne of Denmark, and therefore argued that she should receive part of her brother's inheritance from their late grandmother. Initially Charles was accepting of this, but after he found out the vast size of the inheritance, totalling over 430.000 rigsdaler, he changed his mind.[66] However, Christian IV quickly appropriated most of their inheritance, claiming that what he had seized only served to pay part of the English debt from 1620.[67]

During the spring of 1632, several representatives from Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Prussia, Holstein-Gottorp and Mecklenburg, began to arrive at the Danish Court to lodge inheritance demands on behalf of Elizabeth of Denmark's children. Ultimately, the majority of the principal heirs of the body were denied inheritance because they were simultaneously debtors of her estate. This included Charles I, the Dukes of Holstein-Gottorp, Brunswick-Lüneburg, Mecklenburg-Güstrow, and Mecklenburg-Schwerin, but with some exceptions, such as her daughter, Hedwig of Denmark, Electress of Saxony, who received the outstanding Mecklenburg assets, totalling over 360.000 rigsdaler.[68] Most accepted this settlement, while others disputed it fiercely. In particular, Sophie Hedwig, Countess of Nassau-Dietz and Hedwig, Duchess of Pomerania made tenacious demands, and wistfully lamented that they were left empty-handed due to their brother, Frederick Ulrich's debt, from which they themselves had not benefited.[69]

The disputes over inheritance persisted long after Sophie's passing.[50] In 1654, over 20 years after her death, William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz, the son of the aforementioned Countess of Nassau-Diez and Count Ernest Casimir I, launched an appeal to recover his mother’s share of Queen Sophia's inheritance. A Danish envoy was dispatched from the court of Sophie's grandson, Frederick III, and a favourable settlement was negotiated between the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Nassau-Diez.[70]

In the end, Christian IV emerged as the unsurpassed principal beneficiary of Sophie's disposable fortune, but he quickly squandered the inheritance on costly wars with Sweden, his eldest son's wedding and construction activities.[71]

Character and legacy

[edit]

Sophie of Mecklenburg was initially described as a "prudent and capable" woman,[72] but reserved and uninterested in political power.[73] However, this changed dramatically in her widowhood, when she became an assertive figure in conflicts with the Council of the Realm. This transformation earned her descriptions such as "a fury of a mother"[74] and, later in life, a "confident old lady".[75]

Contemporary and historical portrayal

[edit]Contemporary accounts of Sophie's character are divergent, though largely positive in nature, especially from foreign observers. The majority of the limited contemporaneous sources portray her positively. In 1588, Daniel Rodgers, an Anglo-Flemish diplomat employed for Lord Burghley, as a spy to report the characters of the Danish royal family, wrote of Queen Sophie; "She is a right virtous and godly princess, who with a motherly care and great wisdom, ruleth her children".[76][77] When a canon of Lübeck, Hermann von Zesterfleth, visited Denmark in 1600, he noted that the dowager queen was able to extract large sums of revenue from her estate because of her highly efficient agricultural operations and management.[78] When she died in 1631, observers described her as "a lady of great thrift and enterprise", and the secretary to the English Ambassador in Denmark, James Howell, remarked that she was the "richest Queen in Christendom".[14][79]

However, domestic political power dynamics have resulted in a more negative perception of her character, which has left its mark on Danish history.[21] Because of her significant wealth and consequent influence, and undoubtedly exacerbated by earlier disputes with the Council of the Realm about the maturity and regency of Christian IV, she was viewed by some contemporary Danish nobles as being cynical, greedy and avaricious. Later, predominantly male historians echoed these sentiments, dismissing Sophie as having an "economic sense that bordered on avarice,"[80] an "imperious character,"[81] and describing her as being in the grip of her emotions, with a bitter passion, a violent combativeness, and a fierce temperament.[21][33][82] Other historians have treated Sophie superficially or somewhat perfunctorily in footnotes. Historian G.L. Baden, in his History of the Kingdom of Denmark, succinctly described Sophie as "talented".[83]

Sophie's legacy has largely been overshadowed by the story of Frederick II's youthful love affair with the noblewoman Anne Hardenberg. The royal couple's relationship has even been portrayed as unhappy, including by the Danish author H.F. Ewald, who wrote a number of historical novels, including Anna Hardenberg (1880), which brought this flawed narrative into many Danish homes. Likewise, her claim to the role of guardian (and regent) has been judged negatively by earlier historians.[19]

Modern characterization and reappraisals

[edit]Recent reevaluations of Sophie’s life present her in a much more nuanced light. She is now acknowledged as intelligent, industrious and strategic, and determined to consolidate her political influence in the Danish-Norwegian realm, after the Council of the Realm rejected her as guardian of her son in 1588 - something she successfully achieved through immense financial leverage.[21]

She is chiefly remembered for her impressive financial acumen and as the eternal source of pecuniary support for her son Christian IV.[12] She funded some of the greatest Renaissance constructions in Denmark, including Rundetårn, Børsen, and Rosenborg Castle,[84] and also subsidized the rebuilding and expansion of Frederiksborg Castle as well as the restoration of Kronborg following the 1629 fire, that destroyed much of it.[84][85] Although often described as avaricious, this view has since been firmly rejected. As early as 1910, Ellen Jørgensen and Johanne Skovgaard, in their work on Danish queens, emphasized that "Queen Sophie (...) can hardly justifiably be accused of having been mean or ungenerous. Her financial sense was of an active rather than a passive nature, and the significant profits were due to an enterprise that was abundant in initiative rather than in anxious frugality". She funded considerable charitable causes in her estate, notably the construction of hospitals and substantial grants to schools.[86]

Danish historian Benito Scocozza describes her management of the dower estate as having a “firmness and ruthlessness that hardly made her popular on the islands (Lolland and Falster)”,[87] while other historians note that under her authority, "the dowerlands became her little principality, where she was dedicated to the welfare of her subjects and protected them from external enemies and local bailiffs".[88] Sophie is now recognized as "arguably the most prominent landowner of the era". Upon the death of her husband, she "stepped forward authoritatively",[89] and with "tremendous energy" she engaged in a "bitter struggle" to secure her children's economic and political future.[90] Her ability to conduct "able politicking" even influenced her daughter Anne, Queen of Scotland and England, as noted in Nadine Akkermann's 2013 book on court cultures in the early Middle Ages.[91] Literary historian John Leeds Barroll, also describes her as "a highly gifted woman".[39]

Historian Sybil Jack has posited some motives for Sophie's endeavors during her widowhood: denied formal executive political power by the Danish nobility, Sophie became determined to seize economic power. And contrary to her previous undertakings, Sophie was absolutely successful in this regard.[21][8]

Interests

[edit]Sophie was a fervent Lutheran Protestant. Raised by strongly Protestant parents, Sophie was particularly influenced by her attachment to orthodox lutheranism and her animosity towards the "calvinistic religion", which she considered to be the work of the devil.[92] She and her husband were markedly anti-Catholic and supported the teachings of Niels Hemmingsen, but their primary focus was on ensuring religious stability and conformity in Denmark rather than engaging in detailed theological debate.[93]

Sophie’s intellectual interests were diverse. She was highly erudite, with a particular affinity for books of a theological nature, but she also had a strong interest in folk culture and music. She occupies a very special place in history as the driving force behind Anders Sørensen's ‘Hundred Song Book’ (Danish: Hundredvisebogen) from 1591, Europe's first ever printed collection of traditional ballads.[94][95]

In addition to her literary pursuits, Sophie was actively involved in extensive correspondence and gift exchanges, described as favoring "a certain magnanimity in gifts".[96] She was referred to as a "splendid lady" who exchanged gifts with various German princely houses and even with the Emperor and the Imperial Court in Prague and Vienna.[97]

Issue

[edit]Sophie and Frederick had seven children:

| Name | Portrait | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elizabeth of Denmark |

|

25 August 1573 | 19 June 1625 | She married on 19 April 1590 Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. They had 10 children. |

| Anne of Denmark |

|

12 December 1574 | 2 March 1619 | She married on 23 November 1589 King James VI of Scotland (later also King James I of England). They had 7 children. |

| Christian IV, King of Denmark and Norway |

|

12 April 1577 | 28 February 1648 | He married firstly on 27 November 1597 Anne Catherine of Brandenburg. They had 7 children.

He married secondly, morganatically, Kirsten Munk. They had 12 children. Christian had at least 5 other illegitimate children. |

| Ulrik of Denmark |

|

30 December 1578 | 27 March 1624 | He became last Bishop of the old Schleswig see (1602–1624),

He became Ulrich II as Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Schwerin (1603–1624). He married Lady Catherine Hahn-Hinrichshagen. |

| Augusta of Denmark |

|

8 April 1580 | 5 February 1639 | She married on 30 August 1596 John Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. They had 8 children. |

| Hedwig of Denmark |

|

5 August 1581 | 26 November 1641 | She married on 12 September 1602 Christian II, Elector of Saxony. The marriage was childless |

| John of Denmark, Prince of Schleswig-Holstein |

|

9 July 1583 | 28 October 1602 | He was betrothed to Tsarevna Ksenia (Xenia) daughter of Boris Godunov, Tsar of Russia, but died before the marriage could take place. |

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon

- ^ "Frederik 2. - Kronborg Slot". kongeligeslotte.dk. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Bach-Nielsen, Carsten (29 June 2015). "Frederik II of Denmark and Sophie of Mecklenburg – a Renaissance Star Couple. A German Royal Representational Form in Denmark?". ICO Iconographisk Post. Nordisk tidskrift för bildtolkning – Nordic Review of Iconography (2): 39–65. ISSN 2323-5586.

- ^ a b Jack 2019, p. 100.

- ^ Danneskiold-Samsøe, Jakob (2004). Muses and Patrons : Cultures of Natural Philosophy in Seventeenth Century Scandinavia (thesis/docmono thesis). Lund University. Page 141

- ^ Gun, W. T. J. (1930). "The heredity of the stewarts: A remarkably varied family". The Eugenics Review. 22 (3): 196. PMC 2984956. PMID 21259951.

- ^ Veerapen 2024, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d Jack 2019, p. 105-106.

- ^ Lockhart 2007, p. 133.

- ^ Dickinson, Fraser John (2021). Anglo-French Relations and the 'Protestant Party': The Earl of Leicester and His Circle, 1636-41 (Doctoral thesis). University of Buckingham. Page 26

- ^ a b c d e Petersen, E. Ladewig (1 January 1982). "Defence, war and finance: Christian iv and the council of the realm 1596–1629". Scandinavian Journal of History. 7 (1–4): 277–313. doi:10.1080/03468758208579010. ISSN 0346-8755.

- ^ a b Petersen, E. Ladewig (1974). Christian IV.s pengeudlån til danske adelige. Kongelig foretagervirksomhed og adelig gældstiftelse 1596-1625 [Christian IV's money lending to Danish nobles. Royal enterprise and noble indebtedness 1596-1625.]. Publikation - Institut for økonomsk historie, Københavns universitet ; nr. 8 (in Danish). Institute of Economic History, University of Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag. p. 54. ISBN 978-87-500-1474-4.

Denne evigt uudtømmelige rigdomskilde fik da i praksis karakter af direkte eller indirekte subsidier til den kongelige kabinetspolitik.

- ^ Adams 1997, p. 65.

- ^ a b Taylor 1874, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Jack 2019, p. 105.

- ^ a b Wiesner-Hanks 2024, p. 31.

- ^ Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters (1847). Regesta diplomatica historiae danicae. Index chronologicus diplomatum et literarum, historiam danicam ab antiquissimis temporibus usque ad annum 1660. University of California. Havniae, J.D. Qvist. pp. 774–775.

- ^ Federicia, Julius Albert (1876). Danmarks ydre politiske historie i tiden fra freden i Lybek til freden i Kjøbenhavn (1629-1660). Harvard University. Kjøbenhaven, Hoffensberg, Jespersen & F. Traps etab. pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Bisgaard 2004, p. 141-142.

- ^ Jørgensen & Skovgaard 1910, p. 139 & 124.

- ^ a b c d e "DRTV - På sporet af dronningerne: Sophie af Mecklenburg, 1557-1631". www.dr.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ Jack 2019, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f Grinder-Hansen, Poul (2013). Frederik II - Danmarks Renæssancekonge. Gyldendal. pp. See Chapter 12, Kærlighed, chapter 24, Private notater. ISBN 978-87-02-13569-5.

- ^ Skaarup, Bi (1994). "Soffye". Skalk - NYT Fra Fortiden. 5 – via Skalk.dk.

- ^ Frederica, J.A. (1892). "Nogle Breve fra Frederik IIs Dronning Sofie til hendes Fader, hertug Ulrich af Meklenborg". Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift. Tredie Række: 1–8.

- ^ Otto, Carøe (1 January 1873). "Kong Frederik II's Kalenderoptegnelser for Aarene 1583, 1584 og 1587". Historisk Tidsskrift. 4 række, 3 bind.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon

- ^ Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts, 1588-1596', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 35.

- ^ a b Jack 2019, p. 104.

- ^ Lolland-Falsters Aarbog 1933. Vol. XXI. Lolland-Falsters Historiske Samfund. 1933. p. 119.

- ^ "Formynderstyre | lex.dk". Danmarkshistorien (in Danish). 23 February 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Mackeprang 1902, p. 528.

- ^ a b Larsen, Birgitte Stoklund; Foredragsholder, Stiftskonsulent Og (27 January 2022). "Hamlet og Holger Danske må vige pladsen: Renæssancen havde sin helt egen wonderwoman på Kronborg". Kristeligt Dagblad (in Danish). Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ "Sag: Dronningens Pakhus, Nakskov". Visit Lolland-Falster (in Danish). Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Erslev 1883, p. 309.

- ^ Ashton 1960, p. 164.

- ^ a b Joost, Sebastian (2010). "Sophie - Deutsche Biographie". www.deutsche-biographie.de. 24 (in German). Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ a b Hanks & Chojnacka 2002, p. Two letters from the dowager queen, Denmark seventeenth century.

- ^ a b Barroll 2005, p. 193.

- ^ "Women in power 1570-1600". www.guide2womenleaders.com. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ Petersen, E. Ladewig (1974). Christian IV.s pengeudlån til danske adelige. Kongelig foretagervirksomhed og adelig gældstiftelse 1596-1625 [Christian IV's money lending to Danish nobles. Royal enterprise and noble indebtedness 1596-1625.]. Publikation - Institut for økonomsk historie, Københavns universitet ; nr. 8 (in Danish). Akademisk Forlag, Institute of Economic History, University of Copenhagen. p. 42. ISBN 978-87-500-1474-4.

- ^ a b c Lauring 2016.

- ^ "Inflation calculator". www.bankofengland.co.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Akkerman 2021, p. 161.

- ^ Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters (1847). Regesta diplomatica historiae danicae. Index chronologicus diplomatum et literarum, historiam danicam ab antiquissimis temporibus usque ad annum 1660. University of California. Havniae, J.D. Qvist. pp. 774–775.

- ^ a b Federicia, Julius Albert (1876). Danmarks ydre politiske historie i tiden fra freden i Lybek til freden i Kjøbenhavn (1629-1660). Harvard University. Kjøbenhaven, Hoffensberg, Jespersen & F. Traps etab. pp. 193–194.

- ^ Federicia, Julius Albert (1876). Danmarks ydre politiske historie i tiden fra freden i Lybek til freden i Kjøbenhavn (1629-1660). Harvard University. Kjøbenhaven, Hoffensberg, Jespersen & F. Traps etab. pp. 124–125.

- ^ Schulenburg, Otto (1892). Die Vertreibung der mecklenburgischen Herzöge Adolf Friedrich und Johann Albrecht durch Wallenstein und ihre Restitution [The expulsion of the Mecklenburg dukes Adolf Friedrich and Johann Albrecht by Wallenstein and their restitution] (in German). Rostock. p. 76.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Olesen, Bernhard (1889). "Dronning Sophies Portrætter på Frederiksborg og Mauritshuis" [Portraits of Queen Sophie at Frederiksborg and Mauritshuis] (PDF). Illustreret Tidende. 40 (14): 226 – via Royal Library, Denmark.

- ^ a b c Scocozza 1987, p. 209.

- ^ a b Friis 1901, p. 138.

- ^ Nielsen & Askholm 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Carøe 1912

- ^ Petersen 2008, p. 296

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 146.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 149.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 142.

- ^ Friis 1901, p. 139.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 147-149.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 148.

- ^ Olsen, Rikke Agnete (2005). Kongerækken [List of Kings]. Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 87-595-2525-8. OCLC 255289738.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 152.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 143.

- ^ Office, Great Britain Public Record (1864). Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Relating to English Affairs, Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy: 1629-1632. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green. p. 569.

- ^ Howell 1892, p. 38.

- ^ Akkerman 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Hull 1993, p. 47.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 154.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 156.

- ^ Schlegel 1775, p. 159-160.

- ^ "Dronning Sophie | Kongernes Samling". www.kongernessamling.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Hougaard, O.; Wedderkop Hedegaard, A., eds. (1918). "Nykøbing-Falster". Købstæderne i Lolland-Falsters Stift (PDF) (in Danish) (I.-VII. ed.). Odense: Dansk Handel & Industri Forlag. pp. 15–17.

- ^ Jørgensen & Skovgaard 1910, p. 121.

- ^ Helleberg, Maria (8 September 2016). Et herregårdsliv - Brahetrolleborg (in Danish). Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 978-87-11-49004-4.

- ^ Poulsen, Vagn; Lassen, Erik (1973). Dansk kunsthistorie: Lassen, E. [and others] Rigets mænd lader sig male, 1500-1750 (in Danish). Politiken. p. 146. ISBN 978-87-567-1603-1.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes (1851). Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman conquest [microform] : now first published from official records & other authentic documents, private as well as public. Canadiana.org. London : Colburn. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-665-49790-2.

- ^ Ellis, Henry (1827). Original Letters, Illustrative of English History. Harding and Lepard. p. 149.

- ^ Scocozza 1989, p. 14-15.

- ^ Repplier, Agnes (1 November 1906). "His Reader's Friend". The Atlantic. ISSN 2151-9463. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Sophie – født 1557". Dansk Biografisk Leksikon | Lex (in Danish). 18 July 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Liisberg, Henrik Carl Bering (1891). Christian IV, Danmarks og Norges konge (in Danish). Bojesen.

- ^ Nielsen & Askholm 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Baden, G. L. (Gustav Ludvig) (1829). Danmarks riges historie [History of the Kingdom of Denmark] (in Danish). New York Public Library. Kjøbenhavn, J.H. Schubothe. p. 435.

- ^ a b "Sophie af Mecklenburg - Dansk dronning 1572-1631 - Lex". Den Store Danske | Lex (in Danish). 12 September 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Nykøbing Falster Turistforenings (2020). "I Dronning Sophies fodspor" (PDF). nykobingfalster.dk. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Jørgensen & Skovgaard 1910, p. 136-138.

- ^ Scocozza 1987, p. 207.

- ^ Jespersen 2022, p. 43.

- ^ Larsen 2021, p. 29.

- ^ Thiedecke 2021, p. Overklassefruerne 6. De Adelige Fruer.

- ^ Fry 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Danmarks riges historie: 1588-1699 af J.A. Fridericia (in Danish). Gyldendalske boghandel. 1907. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Jack 2019, p. 103.

- ^ "Hundredvisebogen". Dansk litteraturs historie | Lex (in Danish). 29 May 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Dahlerup, Pil (30 January 2024). Dansk litteratur. Middelalder 2. Verdslig litteratur (in Danish). Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 978-87-27-13007-1.

- ^ Troels-Lund 1903, p. 44.

- ^ Liisberg, H. C. Bering (21 October 2020). Christian den Fjerde og Guldsmedene (in Danish). Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 978-87-26-30656-9.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Simon (1997). The Thirty Years' War. Routledge & Kegan. ISBN 978-0-7100-9788-0.

- Akkerman, Nadine (2011). The Correspondence of Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia. Vol. II (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199551088.

- Akkerman, Nadine (2021). Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Hearts. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966830-4.

- Ashton, Robert (1960). The Crown and the money market, 1603-1640. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198282198.

- Barroll, John Leeds (2005). "The Court of the first Stuart Queen". In Peck, Linda Levy (ed.). The Mental World of the Jacobean Court. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521021049.

- Bisgaard, Lars (2004). "Den Oldenborgske Linje: Sophie". In Bjørn, Claus; J. V. Jespersen, Knud; Bregnsbo, Michael; Harding, Merete; Bisgaard, Lars (eds.). Danmarks Konger og Dronninger [Denmark's Kings and Queens] (in Danish) (1st ed.). Denmark: Gyldendal. ISBN 8700794759.

- Carøe, Kristian (1912). Studier til dansk medicinalhistorie [Studies in Danish Medical History] (in Danish). Lindhardt & Ringhof. ISBN 9788726428353.

- Erslev, Kristian (1883). Aktstykker og Oplysninger til Rigsraadets og Stændermødernes Historie i Kristian IV's Tid [Documents and Information on the History of the Council of State and the Meetings of the Estates in the Time of Christian IV]. Selskabet for Udgivelse af Kilder til dansk Historie. OL 23378582M.

- Friis, Hans Emil (1901). Brudstykker af det Oldenborgske kongehus' historie [Fractions of the history of the Oldenborg Royal House] (in Danish). H. Hagerups Forlag. OCLC 1178913739.

- Fry, Cynthia (2014). "Perceptions of influence: the Catholic diplomacy of Queen Anna and her ladies, 1601-1604". In Akkerman, Nadine; Houben, Birgit (eds.). The Politics of Female Households. Brill. ISBN 978-9004236066.

- Hanks, Merry Wiesner; Chojnacka, Monica (2002). Ages of Woman, Ages of Man: Sources in European Social History (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9780582418738.

- Howell, James (1892). Jacobs, Joseph (ed.). Epistolae Ho-Elianae. Correspondence. London: D. Nutt.

- Hull, Felix (1993). "Sidney of Penshurst - Robert, 2nd Earl of Leicester". Archaeologia Cantiana. 111: 43–56.

- Jack, Sybil (2019). "Katarina Jagiellonica and Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow: Power, piety, and patronage". In Schutte, Valerie; Paranque, Estelle (eds.). Forgotten Queens in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Political Agency, Myth-Making, and Patronage. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-08545-9.

- Jespersen, Mikkel Leth (2022). Dronningen griber magten: 1387 [The Queen Seizes Power: 1387] (in Danish). Aarhus Universitetsforlag. ISBN 978-8772198064.

- Jørgensen, Ellen; Skovgaard, Johanne (1910). Danske Dronninger: fortaellinger og karakteristikker [Danish Queens: stories and characterisations] (in Danish). H. Hagerup.

- Larsen, Pernille Helena (2021). Glimt af kvindeliv i Danmark gennem 1000 år [Glimpses of women's lives in Denmark over 1000 years] (in Danish). Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 9788728023488.

- Lauring, Palle (2016). Dronninger og andre kvinder i Danmarkshistorien [Queens and other women in Danish history]. Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 9788711622513.

- Lockhart, Paul Douglas (2007). Denmark, 1513-1660: The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927121-4.

- Mackeprang, Mouritz (1902). "Dronning Sofie og livgedinget" [Queen Sofie and the Jointure]. Historisk Tidsskrift (Denmark). 3 (7): 527–555. ISSN 0106-4991.

- Nielsen, Kay; Askholm, Ib (2007). Danmarks Kongelige Familier i 1000 år [Denmark's Royal Families in 1000 years] (in Danish) (1st ed.). Rødovre: Askholmds Forlag. ISBN 9788791679094.

- Petersen, E. Ladewig (1974). "Christian IV.s pengeudlån til danske adelige. Kongelig foretagervirksomhed og adelig gældstiftelse 1596-1625" [Christian IV's money lending to Danish nobles. Royal enterprise and noble indebtedness 1596-1625.]. Akademisk Forlag. 8. Department of Economic History, University of Copenhagen.

- Petersen, E. Ladewig (2008). "Defence, war and finance: Christian IV and the council of the realm 1596–1629". Scandinavian Journal of History. 7 (1–4): 277–313. doi:10.1080/03468758208579010.

- Schlegel, Johann Heinrich (1775). Samlung zur Dänischen Geschichte, Münzkenntniss, Oekonomie und Sprache [Collection on Danish history, coinage, economics and language] (in German). Vol. 2. Copenhagen: H. C. Sander & J. F. Morthorst.

- Scocozza, Benito (1987). Christian 4 (in Danish) (4th ed.). Copenhagen: Politikens Forlag. ISBN 9788756743518.

- Scocozza, Benito (1989). Olsen, Olaf (ed.). Gyldendal og Politikens Danmarkshistorie [Gyldendal and Politiken's History of Denmark] (in Danish). Vol. 8: Ved afgrundens rand. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag. ISBN 978-87-89068-10-7.

- Taylor, Tom (1874). Leicester Square: Its Associations and Its Worthies. Bickers & Son. ISBN 9781142563264.

- Thiedecke, Johnny (2021). Satans store port. Kvinderne og børnene i renæssancens Danmark [The Great Gate of Satan. Women and children in Renaissance Denmark] (in Danish). Lindhardt & Ringhof. ISBN 978-8726711769.

- Troels-Lund, Troels (1903). Dagligt Liv i Norden i det sekstende Århundrede [Daily Life in the Nordics in the Sixteenth Century] (in Danish) (8–10 ed.). Copenhagen: Gyldendal – via New York Public Library.

- Veerapen, Steven (2024). The Wisest Fool: The Lavish Life of James VI and I (1st ed.). Birlinn General. ISBN 978-1780278735.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2024). Women and the Reformations: A Global History (1st ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300268232.

- Wittendorff, Alex (1989). Olsen, Olaf (ed.). Gyldendal og Politikens Danmarkshistorie [Gyldendal and Politiken's History of Denmark] (in Danish). Vol. 7: På Guds og Herskabs nåde. Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag.

KSF

KSF