SpaceX

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 71 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 71 min

Company headquarters, SpaceX Starbase in Starbase, Texas | |

| SpaceX | |

| Company type | Private |

| Industry | |

| Founded | March 14, 2002 in El Segundo, California, U.S.[1] |

| Founder | Elon Musk |

| Headquarters | SpaceX Starbase, , U.S. |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Owner |

|

Number of employees | 13,000+[8] (September 2023) |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | spacex.com |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Companies Politics |

||

Space Exploration Technologies Corp., commonly referred to as SpaceX, is an American space technology company headquartered at the Starbase development site in Starbase, Texas.[10] Since its founding in 2002, the company has made numerous advances in rocket propulsion, reusable launch vehicles, human spaceflight and satellite constellation technology. As of 2025[update], SpaceX is the world's dominant space launch provider, its launch cadence eclipsing all others, including private competitors and national programs like the Chinese space program.[11] SpaceX, NASA, and the United States Armed Forces work closely together by means of governmental contracts.[12]

SpaceX was founded by Elon Musk in 2002 with a vision of decreasing the costs of space launches, paving the way to a self-sustaining colony on Mars. In 2008, Falcon 1 successfully launched into orbit after three failed launch attempts. The company then moved towards the development of the larger Falcon 9 rocket and the Dragon 1 capsule to satisfy NASA's COTS contracts for deliveries to the International Space Station. By 2012, SpaceX finished all COTS test flights and began delivering Commercial Resupply Services missions to the International Space Station. Also around that time, SpaceX started developing hardware to make the Falcon 9 first stage reusable. The company demonstrated the first successful first-stage landing in 2015 and re-launch of the first stage in 2017. Falcon Heavy, built from three Falcon 9 boosters, first flew in 2018 after a more than decade-long development process. As of May 2025, the company's Falcon 9 rockets have landed and flown again more than 450 times, reaching 1–3 launches a week.

These milestones delivered the company much-needed investment and SpaceX sought to diversify its sources of income. In 2019, the first operational satellite of the Starlink internet satellite constellation came online. In subsequent years, Starlink generated the bulk of SpaceX's income and paved the way for its Starshield military counterpart. In 2020, SpaceX began to operate its Dragon 2 capsules to deliver crewed missions for NASA and private entities. Around this time, SpaceX began building test prototypes for Starship, which is the largest launch vehicle in history and aims to fully realize the company's vision of a fully reusable, cost-effective and adaptable launch vehicle. SpaceX is also developing its own space suit and astronaut via its Polaris program[13] as well as developing the human lander for lunar missions under NASA's Artemis program.[14] SpaceX is not publicly traded; a space industry newspaper estimated that SpaceX has a revenue of over $10 billion in 2024.[4]

History

[edit]2001–2004: Founding

[edit]In early 2001, Elon Musk met Robert Zubrin and donated $100,000 to his Mars Society, joining its board of directors for a short time.[15]: 30–31 He gave a plenary talk at their fourth convention where he announced Mars Oasis, a project to land a greenhouse and grow plants on Mars.[16][17] Musk initially attempted to acquire a Dnepr launch vehicle for the project through Russian contacts from Jim Cantrell.[18]

Musk returned with his team to Moscow, this time bringing Michael Griffin, who later became the 11th Administrator of NASA, but found the Russians increasingly unreceptive.[19][20] On the flight home, Musk announced he could start a company to build the affordable rockets they needed instead.[20] By applying vertical integration,[19] using inexpensive commercial off-the-shelf components when possible,[20] and adopting the modular approach of modern software engineering, Musk believed SpaceX could significantly cut launch costs.[20]

In early 2002, Elon Musk started to look for staff for his company, soon to be named SpaceX. Musk approached five people for the initial positions at the fledgling company, including Griffin, who declined the position of Chief Engineer,[21]: 11 Jim Cantrell and John Garvey (Cantrell and Garvey later founded the company Vector Launch), rocket engineer Tom Mueller, and Chris Thompson.[21][22] SpaceX was first headquartered in a warehouse in El Segundo, California. Early SpaceX employees, such as Tom Mueller (CTO), Gwynne Shotwell (COO), and Chris Thompson (VP of Operations), came from neighboring TRW and Boeing corporations. By November 2005, the company had 160 employees.[23] Musk personally interviewed and approved all of SpaceX's early employees.[21]: 22

Musk has stated that one of his goals with SpaceX is to decrease the cost and improve the reliability of access to space, ultimately by a factor of ten.[24]

2005–2009: Falcon 1 and first orbital launches

[edit]

SpaceX developed its first orbital launch vehicle, the Falcon 1, with internal funding.[25][26] The Falcon 1 was an expendable two-stage-to-orbit small-lift launch vehicle. The total development cost of Falcon 1 was approximately $90 million[27] to $100 million.[21]: 215

The Falcon rocket series was named after Star Wars's Millennium Falcon fictional spacecraft.[28]

In 2004, SpaceX protested against NASA to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) because of a sole-source contract awarded to Kistler Aerospace. Before the GAO could respond, NASA withdrew the contract, and formed the COTS program.[21]: 109–110 [29] In 2005, SpaceX announced plans to pursue a human-rated commercial space program through the end of the decade, a program that would later become the Dragon spacecraft.[30] In 2006, the company was selected by NASA and awarded $396 million to provide crew and cargo resupply demonstration contracts to the International Space Station (ISS) under the COTS program.[31]

The first two Falcon 1 launches were purchased by the United States Department of Defense under the DARPA Falcon Project which evaluated new U.S. launch vehicles suitable for use in hypersonic missile delivery for Prompt Global Strike.[26][32][33] The first three launches of the rocket, between 2006 and 2008, all resulted in failures, which almost ended the company. Financing for Tesla Motors had failed, as well,[34] and consequently Tesla, SolarCity, and Musk personally were all nearly bankrupt at the same time.[21]: 178–182 Musk was reportedly "waking from nightmares, screaming and in physical pain" because of the stress.[21]: 216

The financial situation started to turn around with the first successful launch achieved on the fourth attempt on September 28, 2008. Musk split his remaining $30 million between SpaceX and Tesla, and NASA awarded the first Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract awarding $1.6 billion to SpaceX in December, thus financially saving the company.[21]: 217–221 Based on these factors and the further business operations they enabled, the Falcon 1 was soon retired following its second successful, and fifth total, launch in July 2009. This allowed SpaceX to focus company resources on the development of a larger orbital rocket, the Falcon 9.[35] Gwynne Shotwell was also promoted to company president at the time, for her role in successfully negotiating the CRS contract with the NASA Associate Administrator Bill Gerstenmaier.[36][21]: 222

2010–2012: Falcon 9, Dragon, and NASA contracts

[edit]SpaceX originally intended to follow its light Falcon 1 launch vehicle with an intermediate capacity vehicle, the Falcon 5.[37] The company instead decided in 2005 to proceed with the development of the Falcon 9, a reusable heavier lift vehicle. Development of the Falcon 9 was accelerated by NASA, which committed to purchasing several commercial flights if specific capabilities were demonstrated. This started with seed money from the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program in 2006.[38] The overall contract award was $278 million to provide development funding for the Dragon spacecraft, Falcon 9, and demonstration launches of Falcon 9 with Dragon.[38] As part of this contract, the Falcon 9 launched for the first time in June 2010 with the Dragon Spacecraft Qualification Unit, using a mockup of the Dragon spacecraft.

The first operational Dragon spacecraft was launched in December 2010 aboard COTS Demo Flight 1, the Falcon 9's second flight, and safely returned to Earth after two orbits, completing all its mission objectives.[39] By December 2010, the SpaceX production line was manufacturing one Falcon 9 and Dragon every three months.[40]

In April 2011, as part of its second-round Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program, NASA issued a $75 million contract for SpaceX to develop an integrated launch escape system for Dragon in preparation for human-rating it as a crew transport vehicle to the ISS.[41] NASA awarded SpaceX a fixed-price Space Act Agreement (SAA) to produce a detailed design of the crew transportation system in August 2012.[42]

In early 2012, approximately two-thirds of SpaceX stock was owned by Musk[43] and his seventy million shares were then estimated to be worth $875 million on private markets,[44] valuing SpaceX at $1.3 billion.[45] In May 2012, with the Dragon C2+ launch, Dragon became the first commercial spacecraft to deliver cargo to the International Space Station.[46] After the flight, the company private equity valuation nearly doubled to $2.4 billion or $20/share.[47][48] By that time, SpaceX had operated on total funding of approximately $1 billion over its first decade of operation. Of this, private equity provided approximately $200 million, with Musk investing approximately $100 million and other investors having put in about $100 million.[49]

SpaceX's active reusability test program began in late 2012 with testing low-altitude, low-speed aspects of the landing technology.[50] The Falcon 9 prototypes performed vertical takeoffs and landings (VTOL). High-velocity, high-altitude tests of the booster atmospheric return technology began in late 2013.[50]

2013–2015: Commercial launches and rapid growth

[edit]

SpaceX launched the first commercial mission for a private customer in 2013. In 2014, SpaceX won nine contracts out of the 20 that were openly competed worldwide.[51] That year Arianespace requested that European governments provide additional subsidies to face the competition from SpaceX.[52][53] Beginning in 2014, SpaceX capabilities and pricing also began to affect the market for launch of U.S. military payloads, which for nearly a decade had been dominated by the large U.S. launch provider United Launch Alliance (ULA).[54] The monopoly had allowed launch costs by the U.S. provider to rise to over $400 million over the years.[55] In September 2014, NASA's Director of Commercial Spaceflight, Kevin Crigler, awarded SpaceX the Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) contract to finalize the development of the Crew Transportation System. The contract included several technical and certification milestones, an uncrewed flight test, a crewed flight test, and six operational missions after certification.[42]

In January 2015, SpaceX raised $1 billion in funding from Google and Fidelity Investments, in exchange for 8.33% of the company, establishing the company valuation at approximately $12 billion.[56] The same month SpaceX announced the development of a new satellite constellation, called Starlink, to provide global broadband internet service with 4,000 satellites.[57]

The Falcon 9 had its first major failure in late June 2015, when the seventh ISS resupply mission, CRS-7 exploded two minutes into the flight. The problem was traced to a failed two-foot-long steel strut that held a helium pressure vessel, which broke free due to the force of acceleration. This caused a breach and allowed high-pressure helium to escape into the low-pressure propellant tank, causing the failure.[58]

2015–2017: Reusability milestones

[edit]

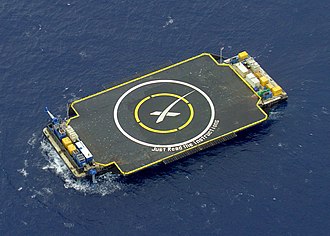

SpaceX first achieved a successful landing and recovery of a first stage in December 2015 with Falcon 9 Flight 20.[59] In April 2016, the company achieved the first successful landing on the autonomous spaceport drone ship (ASDS) Of Course I Still Love You in the Atlantic Ocean.[60] By October 2016, following the successful landings, SpaceX indicated they were offering their customers a 10% price discount if they choose to fly their payload on a reused Falcon 9 first stage.[61]

A second major rocket failure happened in early September 2016, when a Falcon 9 exploded during a propellant fill operation for a standard pre-launch static fire test. The payload, the AMOS-6 communications satellite valued at $200 million, was destroyed.[62] The explosion was caused by the liquid oxygen that is used as propellant turning so cold that it solidified and ignited with carbon composite helium vessels.[63] Though not considered an unsuccessful flight, the rocket explosion sent the company into a four-month launch hiatus while it worked out what went wrong. SpaceX returned to flight in January 2017.[64]

In March 2017, SpaceX launched a returned Falcon 9 for the SES-10 satellite. This was the first time a re-launch of a payload-carrying orbital rocket went back to space.[65] The first stage was recovered again, also making it the first landing of a reused orbital class rocket.[66]

2017–2018: Leading global commercial launch provider

[edit]In July 2017, the company raised $350 million, which raised its valuation to $21 billion.[67] In 2017, SpaceX achieved a 45% global market share for awarded commercial launch contracts.[68] By March 2018, SpaceX had more than 100 launches on its manifest representing about $12 billion in contract revenue.[69] The contracts included both commercial and government (NASA/DOD) customers.[70] This made SpaceX the leading global commercial launch provider measured by manifested launches.[71]

In 2017, SpaceX formed a subsidiary, The Boring Company,[72] and began work to construct a short test tunnel on and adjacent to the SpaceX headquarters and manufacturing facility, using a small number of SpaceX employees,[73] which was completed in May 2018,[74] and opened to the public in December 2018.[75] During 2018, The Boring Company was spun out into a separate corporate entity with 6% of the equity going to SpaceX, less than 10% to early employees, and the remainder of the equity to Elon Musk.[75]

Since 2019: Starship, first crewed launches, Starlink and general

[edit]In 2019 SpaceX raised $1.33 billion of capital across three funding rounds.[76] By May 2019, the valuation of SpaceX had risen to $33.3 billion[77] and reached $36 billion by March 2020.[78]

On August 19, 2020, after a $1.9 billion funding round, one of the largest single fundraising pushes by any privately held company, SpaceX's valuation increased to $46 billion.[79][80][81]

In February 2021, SpaceX raised an additional $1.61 billion in an equity round from 99 investors[82] at a per share value of approximately $420,[81] raising the company valuation to approximately $74 billion. By 2021, SpaceX had raised more than $6 billion in equity financing. Most of the capital raised since 2019 has been used to support the operational fielding of the Starlink satellite constellation and the development and manufacture of the Starship launch vehicle.[82] By October 2021, the valuation of SpaceX had risen to $100.3 billion.[83] On April 16, 2021, Starship HLS won a contract to play a critical role in the NASA crewed spaceflight Artemis program.[84] By 2021, SpaceX had entered into agreements with Google Cloud Platform and Microsoft Azure to provide on-ground computer and networking services for Starlink.[85] A new round of financing in 2022 valued SpaceX at $127 billion.[86]

In July 2021, SpaceX unveiled another drone ship named A Shortfall of Gravitas, landing a booster from CRS-23 on it for the first time on August 29, 2021.[87] Within the first 130 days of 2022, SpaceX had 18 rocket launches and two astronaut splashdowns. On December 13, 2021, company CEO Elon Musk announced that the company was starting a carbon dioxide removal program that would convert captured carbon into rocket fuel,[88][89] after he announced a $100 million donation to the X Prize Foundation the previous February to provide the monetary rewards to winners in a contest to develop the best carbon capture technology.[90][91]

In August 2022, Reuters reported that the European Space Agency (ESA) began initial discussions with SpaceX that could lead to the company's launchers being used temporarily, given that Russia blocked access to Soyuz rockets amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[92] Since that invasion and in the greater war between Russia and Ukraine, Starlink was extensively used.[93]

In 2022, SpaceX's Falcon 9 also became the world record holder for the most launches of a single vehicle type in a single year.[94][95][non-primary source needed] SpaceX launched a rocket approximately every six days in 2022, with 61 launches in total. All but one (a Falcon Heavy in November) was on a Falcon 9 rocket.[94]

In November 2023, SpaceX announced it would acquire its parachute supplier Pioneer Aerospace out of bankruptcy for $2.2 million.[96][97]

On July 16, 2024, Elon Musk posted on X that SpaceX would move its headquarters from Hawthorne, California, to SpaceX Starbase in Brownsville, Texas. Musk said this was because the recently passed California AB1955 bill "and the many others that preceded it, attacking both families and companies".[98] This new law in California bans school districts from requiring that teachers notify parents about changes to a student's sexual orientation and gender identity.[99] The headquarters officially moved to Brownsville, Texas in August 2024, according to records filed with the California Secretary of State.[100] The move to relocate SpaceX's headquarters was seen as largely symbolic, at least in the short term. The Hawthorne facility continues to support the company's Falcon launch vehicles, which was SpaceX's workhorse product in 2024.[101]

SpaceX's 2024 Polaris Dawn mission featured the first-ever private spacewalk, marking a major milestone in commercial space exploration.[102]

In 2025 ProPublica reported that Chinese investors were investing in SpaceX via offshore entities, such as the Cayman Islands. Experts speculated that this might raise national security concerns with regulators.[103]

By July 2025, as part of $5 Billion equity raise SpaceX agreed to invest $2 billion in xAI.[104]

Starship

[edit]

In January 2019, SpaceX announced it would lay off 10% of its workforce to help finance the Starship and Starlink projects.[105] The purpose of the Starship vehicle is to enable large-scale transit of humans and cargo to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.[106] SpaceX's Starship is the largest and most powerful rocket ever flown, with a planned payload capacity of 100+ tons.[107][108] Construction of initial prototypes and tests for Starship started in early 2019 in Florida and Texas. All Starship construction and testing moved to the new SpaceX South Texas launch site later that year.

On April 20, 2023, Starship's first orbital flight test ended in a mid-air explosion over the Gulf of Mexico before booster separation. After launch, multiple engines in the booster progressively failed, causing the vehicle to reach max q later than planned. "Max q" is the theoretical point of maximal mechanical stress which occurs during the launch sequence of a space vehicle. In the case of a rocket that must be self-destructed during its ascent, max q occurs at the point of self-destruction. Eventually, the vehicle lost control and spun erratically until the automated flight termination system was activated, which intentionally destroyed the rocket. Elon Musk, SpaceX, and other individuals familiar with the space industry have referred to the test flight as a success.[109][110]

Musk said at the time that it would take "six to eight weeks" to get the infrastructure prepared for another launch. In October 2023, a senior SpaceX executive stated the company had been ready to launch the next test flight since September. He accused government regulators of disrupting the project's progress, adding the delay could lead to China beating U.S. astronauts back to the Moon.[111][112]

On November 18, 2023, SpaceX launched Starship on its second flight test, with both vehicles flying for a few minutes before separately exploding.[113][114][115][116]

In early March 2024 SpaceX announced that it was targeting March 14 as the tentative launch date for its next uncrewed Starship launch configuration flight test, pending the issuance of a "launch license" by the FAA. This license was granted on March 13, 2024.[117] On March 14, 2024, at 13:25 UTC, Starship launched for the third time and for the first time Starship reached its planned suborbital trajectory. The flight ended with the booster experiencing a malfunction shortly before landing and the ship being lost during re-entry over the Indian Ocean.[107][108]

On June 4, 2024, SpaceX received the launch license for Starship's fourth flight test. The licensure itself was notable in that it was the first time that the FAA included a clause that would allow SpaceX to launch subsequent test flights without a mishap investigation, provided that they met a similar launch profile and used the same specification of hardware. The provision could prove to speed the development timeline.[118]

On October 12, 2024, SpaceX received FAA approval for Starship's fifth flight test.[119] The flight was the first without engine failures, and the first successful tower catch.[120]

SpaceX launched Starship on its sixth flight test on November 19, 2024.[121] The booster aborted the catch attempt, while the ship conducted a relight in space.[122][123]

On January 16, 2025, SpaceX launched Starship on its seventh flight test, with the first Block 2 Ship, Ship 33 (standing at 403 ft or 123 meters). This test also carried a demonstration payload, a Starlink V3 simulator. The test launched at 22:37 UTC. The test resulted in the second catch of the Super Heavy booster, B14, but after 8 minutes, SpaceX lost contact with 'Ship', which is the upper stage of the Starship which resulted in the failure of the ship during the ascent. The spacecraft reportedly exploded around 8.5 minutes after launch over the Atlantic Ocean near the Turks and Caicos Islands. The FAA, on January 18, required a mishap investigation of the failure.[124]

On March 7, 2025, SpaceX launched another Starship rocket, this time from Texas. Contact was lost minutes into the test flight and the spacecraft came tumbling down and broke apart, with wreckage seen across Florida's skies.[125] As per preliminary investigation, Starship’s 7th test flight was disrupted by an oxygen leak, flashes and sustained fires in its aft section, which caused the rocket’s engines to shut down and turn on the spacecraft’s self-destruct system.[126]

On June 18, 2025, a SpaceX Starship rocket exploded during a static fire test at the company’s Starbase facility in Texas, following what the company described as a “major anomaly”.[127]

Crewed launches

[edit]

A significant milestone was achieved in May 2020, when SpaceX successfully launched two NASA astronauts (Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken) into orbit on a Crew Dragon spacecraft during Crew Dragon Demo-2, making SpaceX the first private company to send astronauts to the International Space Station and marking the first crewed orbital launch from American soil in 9 years.[128][129] The mission launched from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) in Florida.[130]

Starlink

[edit]In May 2019, SpaceX launched the first large batch of 60 Starlink satellites, beginning to deploy what would become the world's largest commercial satellite constellation the following year.[131] In 2022, most SpaceX launches focused on Starlink, a consumer internet business that sends batches of internet-beaming satellites and now has over 6,000 satellites in orbit.[132]

On July 16, 2021, SpaceX entered an agreement to acquire Swarm Technologies, a private company building a low Earth orbit satellite constellation for communications with Internet of things (IoT) devices, for $524 million.[133][134]

In December 2022, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the launch of up to 7,500 of SpaceX's next-generation satellites in its Starlink internet network.[135]

Summary of achievements

[edit]| Date | Achievement | Flight |

|---|---|---|

| September 28, 2008 | First privately funded, fully liquid-fueled rocket to reach orbit.[136] | Falcon 1 Flight 4 |

| July 14, 2009 | First privately funded, fully liquid-fueled rocket to put a commercial satellite in orbit. | Falcon 1 Flight 5 |

| December 9, 2010 | First private company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft. | SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 1 |

| May 25, 2012 | First private company to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS).[137] | SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 2 |

| December 22, 2015 | First landing of an orbital-class rocket's first stage on land. | Falcon 9 Flight 20 |

| April 8, 2016 | First landing of an orbital-class rocket's first stage on an ocean platform. | SpaceX CRS-8 |

| March 30, 2017 | First reuse and (second) landing of an orbital first stage.[65] | SES-10 |

| First controlled flyback and recovery of a payload fairing.[138] | ||

| June 3, 2017 | First reuse of a commercial cargo spacecraft.[139] | SpaceX CRS-11 |

| February 6, 2018 | First private spacecraft launched into heliocentric orbit. | Falcon Heavy test flight |

| March 2, 2019 | First private company to send a human-rated spacecraft to orbit. | Crew Dragon Demo-1 |

| March 3, 2019 | First private company to autonomously dock a human-rated spacecraft to the ISS. | |

| July 25, 2019 | First flight of a full-flow staged combustion cycle engine (Raptor).[140] | Starhopper |

| November 11, 2019 | First reuse of a payload fairing.[141] | Starlink 2 v1.0 |

| May 30, 2020 | First private company to send humans into orbit.[142] | Crew Dragon Demo-2 |

| First private company to send humans to the ISS.[143] | ||

| January 24, 2021 | Most spacecraft launched on a single mission, 143 satellites.[a][144] | Transporter-1 |

| April 23, 2021 | First reuse of a crewed space capsule.[145] | SpaceX Crew-2 / Endeavour |

| First reused booster to send humans into orbit. | ||

| June 17, 2021 | First reused booster to launch a 'national security' mission.[146] | GPS III-05 |

| September 16, 2021 | First orbital launch of an all-private crew.[147][148] | Inspiration4 |

| November 24, 2021 | Longest streak of orbital launches without a mission failure or partial failure for a single rocket type (Falcon 9, 101 launches).[149] | Double Asteroid Redirection Test |

| April 9, 2022 | First all-private crew to dock with the International Space Station.[150] | Axiom Mission 1 |

| October 20, 2022 | Highest number of launches of a single rocket type in a calendar year (Falcon 9, 48 launches).[151] | Starlink 4-36 |

| April 20, 2023 | Tallest, most massive, most powerful rocket to ever launch.[152][153] | SpaceX Starship orbital test flight |

| March 14, 2024 | Starship reaches intended orbital velocity for the first time.[154] | SpaceX Starship integrated flight test 3 |

| April 12, 2024 | A single Falcon 9 booster reused for the 20th time.[155] | Booster 1062 |

| September 12, 2024 | First commercial spacewalk | Polaris Dawn |

| October 13, 2024 | First Super Heavy booster catch | Starship flight test 5 |

| November 19, 2024 | First in space relight of a full-flow staged combustion cycle engine (Raptor).[122] | Starship flight test 6 |

- ^ Excluding the passive objects launched as part of Project West Ford

Hardware

[edit]Launch vehicles

[edit]

SpaceX has developed three launch vehicles. The small-lift Falcon 1 was the first launch vehicle developed and was retired in 2009. The medium-lift Falcon 9 and the heavy-lift Falcon Heavy are both operational.

Falcon 1 was a small rocket capable of placing several hundred kilograms into low Earth orbit. It launched five times between 2006 and 2009, of which two were successful.[156] The Falcon 1 was the first privately funded, liquid-fueled rocket to reach orbit.[136]

Falcon 9 is a medium-lift launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 22,800 kilograms (50,265 lb) to orbit, competing with the Delta IV and the Atlas V rockets, as well as other launch providers around the world. It has nine Merlin engines in its first stage. The Falcon 9 v1.0 rocket successfully reached orbit on its first attempt on June 4, 2010. Its third flight, COTS Demo Flight 2, launched on May 22, 2012, and launched the first commercial spacecraft to reach and dock with the International Space Station (ISS).[46] The vehicle was upgraded to Falcon 9 v1.1 in 2013, Falcon 9 Full Thrust in 2015, and finally to Falcon 9 Block 5 in 2018. The first stage of Falcon 9 is designed to retro propulsively land, be recovered, and flown again.[157]

Falcon Heavy is a heavy-lift launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 63,800 kg (140,700 lb) to Low Earth orbit (LEO) or 26,700 kg (58,900 lb) to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). It uses three slightly modified Falcon 9 first-stage cores with a total of 27 Merlin 1D engines.[158][159] The Falcon Heavy successfully flew its inaugural mission on February 6, 2018, launching Musk's personal Tesla Roadster into heliocentric orbit.[160]

Both the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy are certified to conduct launches for the National Security Space Launch (NSSL).[161][162] As of August 14, 2025, the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy have been launched 527 times, resulting in 524 full mission successes, one partial success, and one in-flight failure. In addition, a Falcon 9 experienced a pre-flight failure before a static fire test in 2016.[163][164]

SpaceX is developing a fully reusable super-heavy lift launch system known as Starship. It comprises a reusable first stage, called Super Heavy, and the reusable Starship second stage space vehicle. As of 2017[update], the system was intended to supersede the company's existing launch vehicle hardware by the early 2020s.[165][166]

Rocket engines

[edit]

Since the founding of SpaceX in 2002, the company has developed several rocket engines – Merlin, Kestrel, and Raptor – for use in launch vehicles,[167][168] Draco for the reaction control system of the Dragon series of spacecraft,[169] and SuperDraco for abort capability in Crew Dragon.[170]

Merlin is a family of rocket engines that uses liquid oxygen (LOX) and RP-1 propellants. Merlin was first used to power the Falcon 1's first stage and is now used on both stages of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy vehicles.[171] Kestrel uses the same propellants and was used as the Falcon 1 rocket's second-stage main engine.[168][172]

Draco and SuperDraco are hypergolic liquid-propellant rocket engines. Draco engines are used on the reaction control system of the Dragon and Dragon 2 spacecraft.[169] The SuperDraco engine is more powerful, and eight SuperDraco engines provide launch escape capability for crewed Dragon 2 spacecraft during an abort scenario.[173]

Raptor is a new family of liquid oxygen and liquid methane-fueled full-flow staged combustion cycle engines to power the first and second stages of the in-development Starship launch system.[167] Development versions were test-fired in late 2016,[174] and the engine flew for the first time in 2019, powering the Starhopper vehicle to an altitude of 20 m (66 ft).[175]

Dragon spacecraft

[edit]

SpaceX has developed the Dragon spacecraft to transport cargo and crew to the International Space Station (ISS).

The first-generation Dragon 1 spacecraft was used only for cargo operations. It was developed with financial support from NASA under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program. After a successful COTS demonstration flight in 2010, SpaceX was chosen to receive a Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract.[39]

The currently operational second-generation Dragon 2 spacecraft conducted its first flight, without crew, to the ISS in early 2019, followed by a crewed flight of Dragon 2 in 2020.[128] It was developed with financial support from NASA under the Commercial Crew Program program. The cargo variant of Dragon 2 flew for the first time in December 2020, for a resupply to the ISS as part of the CRS contract with NASA.[176]

In March 2020 SpaceX revealed the Dragon XL, designed as a resupply spacecraft for NASA's planned Lunar Gateway space station under a Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) contract.[177] Dragon XL is planned to launch on the Falcon Heavy, and is able to transport over 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) to the Gateway. Dragon XL will be docked at the Gateway for six to twelve months at a time.[178]

SpaceX designed a spacesuit to be worn inside the Dragon spacecraft to protect from possible depressurization.[179] On May 4, 2024, SpaceX unveiled a second spacesuit designed for extravehicular activity, planned to be used for a spacewalk during the Polaris Dawn mission.[180]

Autonomous spaceport drone ships

[edit]

SpaceX routinely returns the first stage of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets after orbital launches. The rocket lands at a predetermined landing site using only its propulsion systems.[181] When propellant margins do not permit a return to a launch site (RTLS), rockets return to a floating landing platform in the ocean, called autonomous spaceport drone ships (ASDS).[182]

SpaceX also had plans to introduce floating launch platforms, which would be modified oil rigs provide a sea launch option for their Starship launch vehicle. As of February 2023, SpaceX had sold the oil rigs, but had not ruled out sea-based platforms for future use.[183]

Starlink

[edit]

Starlink is an internet satellite constellation under development by Starlink Services, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of SpaceX,[9][184] that consists of thousands of cross-linked communications satellites in ~550 km orbits. Its goal is to address the significant unmet demand worldwide for low-cost broadband capabilities.[185] Development began in 2015, and initial prototype test-flight satellites were launched on the SpaceX Paz satellite mission in 2017. In May 2019, SpaceX launched the first batch of 60 satellites aboard a Falcon 9.[186] Initial test operation of the constellation began in late 2020[187] and first orders were taken in early 2021.[188] Customers were told to expect internet service speeds of 50 Mbit/s to 150 Mbit/s and latency from 20 ms to 40 ms.[189] In December 2022, Starlink reached over 1 million subscribers worldwide.[190]

The planned large number of Starlink satellites has been criticized by astronomers due to concerns over light pollution,[191][192][193] with the brightness of Starlink satellites in both optical and radio wavelengths interfering with scientific observations.[194] In response, SpaceX has implemented several upgrades to Starlink satellites aimed at reducing their brightness.[195] The large number of satellites employed by Starlink also creates long-term dangers of space debris collisions.[196][197] However, the satellites are equipped with krypton-fueled Hall thrusters which allow them to de-orbit at the end of their life. They are also designed to autonomously avoid collisions based on uplinked tracking data.[198]

In December 2022, SpaceX announced Starshield, a program to incorporate military or government entity payloads on board a Starlink-derived satellite bus. The Space Development Agency is a key customer procuring satellites for a space-based missile defense system.[199][200]

In June 2024, SpaceX introduced a compact version of its Starlink antennas, the "Starlink Mini", designed for mobile satellite internet use. Offered for $599 in an early access release, it was more expensive than the base model. The Mini antenna, half the size and one-third the weight of the Standard version, featured a built-in WiFi router, lower power consumption, and over 100 Mbit/s download speeds.[201]

Other projects

[edit]Hyperloop

[edit]In June 2015, SpaceX announced that it would sponsor a Hyperloop competition, and would build a 1.6 km (0.99 mi) long subscale test track near SpaceX's headquarters for the competitive events.[202][203] The company held the annual competition from 2017 to 2019.[204]

COVID-19 antibody-testing program

[edit]In collaboration with doctors and academic researchers, SpaceX invited all employees to participate in the creation of a COVID-19 antibody-testing program in 2020. As such, 4300 employees volunteered to provide blood samples resulting in a peer-reviewed scientific paper crediting eight SpaceX employees as coauthors and suggesting that a certain level of COVID-19 antibodies may provide lasting protection against the virus.[205][206]

Other

[edit]In July 2018, Musk arranged for his employees to build a mini-submarine to assist the rescue of children stuck in a flooded cavern in Thailand.[207] Richard Stanton, leader of the international rescue diving team, encouraged Musk to facilitate the construction of the vehicle as a backup in case flooding worsened. However, Stanton later concluded that the mini-submarine would not work and said that Musk's involvement "distracted from the rescue effort".[208][209] Engineers at SpaceX and The Boring Company built the mini-submarine from a Falcon 9 liquid oxygen transfer tube in eight hours and personally delivered it to Thailand.[210][211] Thai authorities ultimately declined to use the submarine, stating that it wasn't practical for the rescue mission.[207]

Facilities

[edit]SpaceX is headquartered at the SpaceX Starbase near Brownsville, Texas, where it manufactures and launches its Starship vehicle. However most of the company's operations are based out of its office in Hawthorne, California where it was previously headquartered, where it builds Falcon rockets and Dragon spacecraft, and where it houses its mission control.

The company also operates a Starlink satellite manufacturing facilities in Redmond, Washington, a rocket development and test facility in McGregor, Texas,[212] and maintains an office in the Washington, D.C. area, close to key government customers.[213]

SpaceX has two active launch sites in Florida, one active launch site in California and one active launch site at Starbase in Texas.

Hawthorne, CA: Falcon and Dragon manufacturing, mission control

[edit]

SpaceX operates a large facility in the Los Angeles suburb of Hawthorne, California. The three-story building, originally built by Northrop Corporation to build Boeing 747 fuselages,[214] houses SpaceX's office space, mission control, and Falcon 9 manufacturing facilities.[215]

The area has one of the largest concentrations of space sector headquarters, facilities, and subsidiaries in the U.S., including Boeing/McDonnell Douglas main satellite building campuses, The Aerospace Corporation, Raytheon, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, United States Space Force's Space Systems Command at Los Angeles Air Force Base, Lockheed Martin, BAE Systems, Northrop Grumman, and AECOM, etc., with a large pool of aerospace engineers and recent college engineering graduates.[214]

SpaceX uses a high degree of vertical integration in the production of its rockets and rocket engines.[19] SpaceX builds its rocket engines, rocket stages, spacecraft, principal avionics and all software in-house in their Hawthorne facility, which is unusual for the space industry.[19]

The Hawthorne facility was SpaceX's headquarters until August 2024. However, the move to relocate SpaceX's headquarters was seen as largely symbolic, at least in the short term, as the facility will remain to the company's operations.[216]

Starbase, TX: Starship manufacturing, launch

[edit]

SpaceX manufactures and flies Starship test vehicles from the SpaceX Starbase in Boca Chica near Brownsville, Texas, having announced first plans for the launch facility in August 2014.[217][218] The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued the permit in July 2014.[219] SpaceX broke ground on the new launch facility in 2014 with construction ramping up in the latter half of 2015,[220] with the first suborbital launches from the facility in 2019[215] and orbital launches starting in 2023.

SpaceX has faced increased scrutiny over the environmental impact of its Starbase facility.[221][222][223] In August 2024, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality cited SpaceX for violating environmental regulations by repeatedly releasing pollutants into water near the Boca Chica launch site.[224] The EPA fined SpaceX approximately $150,000 for allegedly discharging "industrial wastewater" and violating the Clean Water Act.[225]

McGregor, TX: Rocket Development and Test Facility

[edit]

SpaceX's Rocket Development and Test Facility in McGregor, Texas is a rocket engine test facility. Every rocket engine and thruster manufactured by SpaceX must pass through McGregor for final testing being used on flight missions.[226][227] The facility also serves as a testing ground for various components and engines during the research and development process.[228] In addition to engine testing, after splashdown and recovery, Dragon spacecraft make a stop at McGregor to have their hazardous hypergolic propellant fuels removed, before the capsules continue on to Hawthorne for refurbishment.[226]

SpaceX calls the facility the most advanced and active rocket engine test facility in the world, and said that as of 2024[update], over 7,000 tests had been conducted at the facility since it opened, with seven engine test fires on a typical day, across more than a dozen test stands.[229] Despite its low-profile compared to the company's other facilities, is a critical part of SpaceX's operations, and company president and COO Gwynne Shotwell maintains her primary office in McGregor.[230][226]

Originally the site of the Bluebonnet Ordnance Plant during World War II,[228] the facility was later used by Beal Aerospace before being leased by SpaceX in 2003.[231] The company has since expanded it significantly from 256 acres (104 ha) in 2003[228] to 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) by 2015.[229] In July 2021, SpaceX announced plans to build a second production facility for Raptor engines at McGregor. This expansion is expected to significantly increase SpaceX's production capacity, with the goal of producing 800 to 1,000 Raptor engines per year.[232][233]

Starlink manufacturing facilities

[edit]

SpaceX's Starlink subsidiary operates over two main facilities. Satellite manufacturing takes place near Seattle, Washington while user terminal manufacturing takes place near Austin, Texas.

Starlink's satellite development and manufacturing operations campus occupies over 314,000 square feet (29,200 m2) in at least six buildings located in Redmond, Washington, east of Seattle. The first building opened in early 2015,[234] and the company later expanded into five buildings on the Redmond Ridge Corporate Center.[235][236]

Starlink opened a user terminal manufacturing facility just outside of Bastrop, Texas, east of Austin in December 2023. In its first nine months of operation, the one-million-square-foot (93,000 m2) facility produced one million user terminals and was on track to become the largest factory for printed circuit boards in the United States.[237]

Launch facilities

[edit]

SpaceX operates four orbital launch sites, at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Kennedy Space Center in Florida and Vandenberg Space Force Base in California for Falcon rockets, and Starbase near Brownsville, Texas for Starship. SpaceX has indicated that they see a niche for each of the four orbital facilities and that they have sufficient launch business to fill each pad.[238] The Vandenberg launch site enables highly inclined orbits (66–145°), while Cape Canaveral and Kennedy enable orbits of medium inclination (28.5–55°).[239] Larger inclinations, including SSO, are possible from Florida by overflying Cuba.[240]

Before it was retired, all Falcon 1 launches took place at the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Omelek Island of the Marshall Islands.[241]

In April 2007, the Pentagon approved the use of Cape Canaveral Space Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40) by SpaceX.[242] The site has been used since 2010 for Falcon 9 launches, mainly to low Earth and geostationary orbits. The former Launch Complex 13 at Cape Canaveral, now renamed Landing Zones 1 and 2, has since 2015 been used for Falcon 9 first-stage booster landings.[243] Later on, SpaceX will retire these two landing zones and add three landing zones for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets to conduct to "Return-to-launch-site" landings, two at LC-39A and one at SLC-40.[244][245][246]

Vandenberg Space Launch Complex 4 (SLC-4E) was leased from the military in 2011 and is used for payloads to polar orbits. The Vandenberg site can launch both Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy vehicles,[247] but cannot launch to low inclination orbits. The neighboring SLC-4W was converted to Landing Zone 4 in 2015 for booster landings.[248]

On April 14, 2014, SpaceX signed a 20-year lease for Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A.[249] The pad was subsequently modified to support Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches. As of 2024[update] it is the only pad that supports Falcon Heavy launches. SpaceX launched its first crewed mission to the ISS from Launch Pad 39A on May 30, 2020.[250] Pad 39A has been prepared since 2019 to eventually accommodate Starship launches. With delays in launch FAA permits for Boca Chica, Texas, the 39A Starship preparation was accelerated in 2022.[251]

Contracts

[edit]SpaceX won demonstration and actual supply contracts from NASA for the International Space Station (ISS) with technology the company developed. SpaceX is also certified for U.S. military launches of Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle-class (EELV) payloads. With approximately thirty missions on the manifest for 2018 alone, SpaceX represented over $12 billion under contract.[70]

Cargo to ISS

[edit]

In 2006, SpaceX won a NASA Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) Phase 1 contract to demonstrate cargo delivery to the ISS, with a possible contract option for crew transport.[252] Through this contract, designed by NASA to provide "seed money" through Space Act Agreements for developing new capabilities, NASA paid SpaceX $396 million to develop the cargo configuration of the Dragon spacecraft, while SpaceX developed the Falcon 9 launch vehicle with their resources.[253] These Space Act Agreements have been shown to have saved NASA millions of dollars in development costs, making rocket development 4–10 times less expensive than if produced by NASA alone.[254]

In December 2010, with the launch of the SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 1 mission, SpaceX became the first private company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft.[255] Dragon successfully berthed with the ISS during SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 2 in May 2012, a first for a private spacecraft.[256]

Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) is a series of contracts awarded by NASA from 2008 to 2016 for the delivery of cargo and supplies to the ISS on commercially operated spacecraft. The first CRS contracts were signed in 2008 and awarded $1.6 billion to SpaceX for 12 cargo transport missions, covering deliveries to 2016.[257] SpaceX CRS-1, the first of the 12 planned resupply missions, launched in October 2012, achieved orbit, berthed, and remained on station for 20 days, before re-entering the atmosphere and splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.[258]

CRS missions have flown approximately twice a year to the ISS since then. In 2015, NASA extended the Phase 1 contracts by ordering an additional three resupply flights from SpaceX, and then extended the contract further for a total of twenty cargo missions to the ISS.[259][257][260] The final Dragon 1 mission, SpaceX CRS-20, departed the ISS in April 2020, and Dragon was subsequently retired from service. A second phase of contracts was awarded in January 2016 with SpaceX as one of the awardees. SpaceX will fly up to nine additional CRS flights with the upgraded Dragon 2 spacecraft.[261][262] In March 2020, NASA contracted SpaceX to develop the Dragon XL spacecraft to send supplies to the Lunar Gateway space station. Dragon XL will be launched on a Falcon Heavy.[263]

Crewed

[edit]

SpaceX is responsible for the transportation of NASA astronauts to and from the ISS. The NASA contracts started as part of the Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program, aimed at developing commercially operated spacecraft capable of delivering astronauts to the ISS. The first contract was awarded to SpaceX in 2011,[264][265] followed by another in 2012 to continue development and testing of its Dragon 2 spacecraft.[266]

In September 2014, NASA chose SpaceX and Boeing as the two companies that would be funded to develop systems to transport U.S. crews to and from the ISS.[267] SpaceX won $2.6 billion to complete and certify Dragon 2 by 2017. The contracts called for at least one crewed flight test with at least one NASA astronaut aboard. Once Crew Dragon received NASA human-spaceflight certification, the contract required SpaceX to conduct at least two, and as many as six, crewed missions to the space station.[267]

SpaceX completed the first key flight test of its Crew Dragon spacecraft, a Pad Abort Test, in May 2015,[268] and successfully conducted a full uncrewed test flight in early 2019. The capsule docked to the ISS and then splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean.[269] In January 2020, SpaceX conducted an in-flight abort test, the last test flight before flying crew, in which the Dragon spacecraft fired its launch escape engines in a simulated abort scenario.[270]

On May 30, 2020, the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission was launched to the International Space Station with NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, the first time a crewed vehicle had launched from the U.S. since 2011, and the first SpaceX commercial crewed launch to the ISS.[271] The Crew-1 mission was successfully launched to the International Space Station on November 16, 2020, with NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker along with JAXA astronaut Soichi Noguchi,[272] all members of the Expedition 64 crew.[273] On April 23, 2021, Crew-2 was launched to the International Space Station with NASA astronauts Shane Kimbrough and K. Megan McArthur, JAXA astronaut Akihiko Hoshide, and ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet.[274] The Crew-2 mission successfully docked on April 24, 2021.[275]

SpaceX also offers paid crewed spaceflights for private individuals. The first of these missions, Inspiration4, launched in 2021 on behalf of Shift4 Payments CEO Jared Isaacman. The mission launched the Crew Dragon Resilience from the Florida Kennedy Space Center's Launch Complex 39A atop a Falcon 9 launch vehicle, placed the Dragon capsule into low Earth orbit, and ended successfully about three days later when the Resilience splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean. All four crew members received commercial astronaut training from SpaceX. The training included lessons in orbital mechanics, operating in a microgravity environment, stress testing, emergency-preparedness training, and mission simulations.[276]

National defense

[edit]

In 2005, SpaceX announced that it had been awarded an Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract, allowing the United States Air Force to purchase up to $100 million worth of launches from the company.[277] Three years later, NASA announced that it had awarded an IDIQ Launch Services contract to SpaceX for up to $1 billion, depending on the number of missions awarded.[278] In December 2012, SpaceX announced its first two launch contracts with the United States Department of Defense (DoD). The United States Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center awarded SpaceX two EELV-class missions: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) and Space Test Program 2 (STP-2). DSCOVR was launched on a Falcon 9 launch vehicle in 2015, while STP-2 was launched on a Falcon Heavy on June 25, 2019.[279]

The Falcon 9 v1.1 was certified for National Security Space Launch (NSSL) in 2015, allowing SpaceX to contract launch services to the Air Force for any payloads classified under national security.[161] This broke the monopoly held since 2006 by United Launch Alliance (ULA) over U.S. Air Force launches of classified payloads.[280] In April 2016, the U.S. Air Force awarded the first such national security launch to SpaceX to launch the second GPS III satellite for $82.7 million.[281] This was approximately 40% less than the estimated cost for similar previous missions.[282] SpaceX also launched the third GPS III launch on June 20, 2020.[283] In March 2018, SpaceX secured an additional $290 million contract from the U.S. Air Force to launch another three GPS III satellites.[284]

The U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) also purchased launches from SpaceX, with the first taking place on May 1, 2017.[285] In February 2019, SpaceX secured a $297 million contract from the U.S. Air Force to launch another three national security missions, all slated to launch no earlier than FY 2021.[286] In August 2020, the U.S. Space Force awarded its National Security Space Launch (NSSL) contracts for the following 5–7 years. SpaceX won a contract for $316 million for one launch. In addition, SpaceX will handle 40% of the U.S. military's satellite launch requirements over the period.[287]

SpaceX also designs and launches custom military satellites for the Space Development Agency as part of a new missile defense system in low Earth orbit.[288] The constellation would give the United States capabilities to sense, target and potentially intercept nuclear missiles and hypersonic weapons launched from anywhere on Earth.[289] Both China and Russia brought concerns to the United Nations about the program,[290] and various organizations warn it could be destabilizing and trigger an arms race in space.[291][292]

In March 2024, Reuters reported that, as part of a $1.8 billion contract signed with the National Reconnaissance Office in 2021, SpaceX is building a network of hundreds of spy satellites. This new network, Reuters reported, would be able to operate as a swarm in low orbits.[293]

In December 2024, WSJ reported that Musk didn't have access to government secrets.[294]

Launch market competition and pricing pressure

[edit]SpaceX's low launch prices, especially for communications satellites flying to geostationary transfer orbit (GTO), have resulted in market pressure on its competitors to lower their own prices.[19] Prior to 2013, the openly competed comsat launch market had been dominated by Arianespace (flying the Ariane 5) and International Launch Services (flying the Proton).[295] With a published price of $56.5 million per launch to low Earth orbit, Falcon 9 rockets were the least expensive in the industry.[296] European satellite operators are pushing the ESA to reduce launch prices of the Ariane 5 and Ariane 6 rockets as a result of competition from SpaceX.[297]

SpaceX ended the United Launch Alliance (ULA) monopoly of U.S. military payloads when it began to compete for national security launches. In 2015, anticipating a slump in domestic, military, and spy launches, ULA stated that it would go out of business unless it won commercial satellite launch orders.[298] To that end, ULA announced a major restructuring of processes and workforce to decrease launch costs by half.[299][300]

Congressional testimony by SpaceX in 2017 suggested that the NASA Space Act Agreement process of "setting only a high-level requirement for cargo transport to the space station [while] leaving the details to industry" had allowed SpaceX to design and develop the Falcon 9 rocket on its own at a substantially lower cost. According to NASA's own independently verified numbers, SpaceX's total development cost for the Falcon 9 rocket, including the Falcon 1 rocket, was estimated at $390 million. In 2011, NASA estimated that it would have cost the agency about $4 billion to develop a rocket like the Falcon 9 booster based upon NASA's traditional contracting processes, about ten times more.[254] In May 2020, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine remarked that thanks to NASA's investments into SpaceX, the United States has 70% of the commercial launch market, a major improvement since 2012 when there were no commercial launches from the country.[301]

As of 2024, SpaceX operates a Rideshare and Bandwagon (mid inclination) programs. This provides additional competition for small satellite launchers.[302]

Corporate affairs

[edit]Business trends

[edit]| Year | Revenue (billion USD) |

Valuation (billion USD) |

Number of employees |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | ca. 30[303] | ||

| 2003 | |||

| 2004 | |||

| 2005 | ca. 90 (Feb.)[304] ca. 160 (Nov.)[305] | ||

| 2006 | |||

| 2007 | ca. 350 (Aug.)[306] | ||

| 2008 | ca. 600 (Dec.)[307] | ||

| 2009 | > 800 (Dec.)[308] | ||

| 2010 | > 1,000 (June)[309] | ||

| 2011 | ca. 1,300 (Jan.)[310] | ||

| 2012 | 2.4 (June)[311] | ca. 1,800 (May)[312] | |

| 2013 | ca. 3,800 (Oct.)[313] | ||

| 2014 | 10 (Aug.)[314] | ||

| 2015 | 12 (Jan.)[315] | ||

| 2016 | 15 (Nov.)[316] | ca. 5,000 (Nov.)[317] | |

| 2017 | 21 (Nov.)[318] | ca. 7,000 (Nov.)[319] | |

| 2018 | 27 (Apr.)[320] | ||

| 2019 | 33 (May)[321] | > 6,000 (July)[322] | |

| 2020 | 1.8[323] | 46 (Aug.)[324] | |

| 2021 | 2.3[323] | 74 (Feb.)[324] 100 (Oct.)[324] |

> 9,500 (March)[325] |

| 2022 | 4.6[326] | 127 (Aug.)[327] | ca. 12,000 (April)[328] |

| 2023 | 9[329] | 137 (Jan.)[330] 180 (Dec.)[331] |

> 13,000 (Sept.)[332] |

| 2024 | 13.1[4] |

350 (Dec.)[324] | |

| 2025 | ca. 15.5[333] |

ca. 400 (July)[334] |

Board of directors

[edit]| Joined board | Name | Titles |

|---|---|---|

| 2002[336] | Elon Musk | Founder, chairman, CEO and CTO of SpaceX; CEO, Product Architect, and former chairman of Tesla; former chairman of SolarCity[336] |

| 2002[337] | Kimbal Musk | Board member, Tesla[338] |

| 2009[339] | Gwynne Shotwell | President and COO of SpaceX[340] |

| Luke Nosek | Co-founder, PayPal[341] | |

| Steve Jurvetson | Co-founder, Future Ventures fund[342] | |

| 2010[343] | Antonio Gracias | CEO and Chairman of the Investment Committee at Valor Equity Partners[344] |

| 2015[345] | Donald Harrison | President of global partnerships and corporate development, Google[346] |

Leadership changes

[edit]In November 2022, the company announced COO Gwynne Shotwell and vice president Mark Juncosa would oversee Starbase, its Texas launch facility, along with Omead Afshar, who at the time oversaw operations for Tesla in Texas. Shyamal Patel, who was senior director of operations at the site, would shift to its Cape Canaveral site. CNBC reported that these executive moves demonstrated "the sense of urgency within the company to get Starship flying".[347][348][349]

Workplace culture

[edit]

According to former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, the company overall has a male-dominated employee culture, similar to that of the spaceflight industry in general.[350] In December 2021, claims of workplace sexual harassment from five former SpaceX employees, ranging from interns to full engineers, were published.[351] The former employees claimed to have experienced unwanted advances and uncomfortable interactions.[352] Additionally, the accounts included claims of a culture of sexual harassment existing at the company and one where complaints made to executives, managers, and human resources officers went largely unaddressed.[353]

In May 2022, a Business Insider article alleged that Musk engaged in sexual misconduct with a SpaceX flight attendant in a private jet in 2016 citing an anonymous friend of the flight attendant.[354] In response, some employees collaborated on an open letter condemning "Elon's harmful Twitter behavior".[355] It also asks the company to clearly define SpaceX's "no-asshole" and "zero tolerance" policies, which it says is unequally enforced from one employee to the next. The next day, Gwynne Shotwell announced that those employees who were involved with the letter had been terminated and claimed that unsponsored, unsolicited surveys were sent to employees during the work day and that some felt pressured to sign the letter.[356]

The company has also been described as having a work culture that pushes employees to work excessively and is described as fostering a burnout culture.[357] According to a memo by Blue Origin, a rival aerospace company with a history of lawsuits and anti-SpaceX political lobbying,[358][359][360] SpaceX expected very long work hours, work on weekends, and limited use of holidays.[357]

"SpaceX employees say they’re paying the price for the billionaire’s push to colonize space at breakneck speed" reported Reuters in 2023. An examination of OSHA's records revealed injury rates higher than the industry's averages. In addition, Reuters documented at least 600 previously unreported workplace injuries at SpaceX, including "crushed limbs, amputations, electrocutions, head and eye wounds and one death."[361] [362] The person who died was Lonnie LeBlanc, a former United States Marine.

In June 2024, eight ex-employees, the same who had previously been fired for penning the open letter against Elon Musk, filed a lawsuit against Musk and SpaceX alleging sexual harassment and discrimination.[363][364][365] The lawsuit has since stalled on headquarter jurisdiction grounds. [366][367]

Federal investigations

[edit]In August 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a lawsuit against SpaceX for discriminating against refugees and asylum seekers in its hiring process, alleging that the company violated the Immigration and Nationality Act by rejecting refugees and asylum recipients and hiring only U.S. citizens and permanent residents.[368] SpaceX denied wrongdoing, citing U.S. export control law.[369] In February 2025, the DOJ filed a motion to dismiss the case with prejudice.[369][370]

In December 2024, federal agencies investigated SpaceX for security violations as well as Musk's alleged drug use.[371][372]

Environmental impact

[edit]According to an investigation conducted by NPR, "SpaceX has sometimes ignored environmental regulations as it rushed to fulfill its founder’s vision. With each of its launches, records show, the company discharged tens of thousands of gallons of what regulators classify as industrial wastewater into the surrounding environment."[373] In addition to endangering nearby people, the wastewater poses significant threats to wildlife.[374]

The 2025 SpaceX Starship Flight 7 rocket explosion sent debris into the atmosphere that was spread across the Caribbean Sea. The incident also "released significant amounts of harmful air pollution into the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere."[375]

References

[edit]- ^ "Delaware Business Search (File # 3500808 – Space Exploration Technologies Corp)". Delaware Department of State: Division of Corporations. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "Who is Elon Musk, and what made him big? | Business| Economy and finance news from a German perspective". Deutsche Welle. May 27, 2020. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ "Gwynne Shotwell: Executive Profile & Biography". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c Kuhr, Jack (January 29, 2025). "Estimating SpaceX's 2024 Revenue". Payload. Payload Space Inc. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ "SpaceX". sacra. SACRA, INC. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ Smith, Rich. "How Much Money Did SpaceX Make in 2024?". Nasdaq. The Motley Fool. Retrieved July 10, 2025.

- ^ Maidenberg, Micah; Higgins, Tim (September 5, 2023). "Elon Musk Borrowed $1 Billion From SpaceX in Same Month of Twitter Acquisition". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ "Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief" (PDF). United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023 – via courtlistener.com.

- ^ a b "Order on Review (FCC 23-105)" (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. December 12, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 24, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

After the auction, SpaceX assigned its winning bids to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Starlink.

- ^ Yañez, Alejandra (May 20, 2025). "Cameron County Commissioners Court approves Starbase as new city". Retrieved May 20, 2025.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (June 28, 2024). "Rocket Report: China flies reusable rocket hopper; Falcon Heavy dazzles". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (March 1, 2019). "The marriage of SpaceX and NASA hasn't been easy—but it's been fruitful". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Berger, Eric (September 15, 2024). "So what are we to make of the highly ambitious, private Polaris spaceflight?". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (April 16, 2021). "NASA selects SpaceX to develop crewed lunar lander". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Zubrin, Robert (May 14, 2019). The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-63388-534-9. OCLC 1053572666.

- ^ Mars Society (August 23, 2001). "The Mars Society Inc. Fourth International Convention" (PDF). Mars Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Musk, Elon (May 30, 2009). "Risky Business". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (August 30, 2001). "Millionaires and billionaires: the secret to sending humans to Mars?". SPACEREF. Retrieved March 1, 2022.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e Chaikin, Andrew (January 2012). "Is SpaceX Changing the Rocket Equation?". Air & Space Smithsonian. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Vance, Ashlee (May 14, 2015). "Elon Musk's space dream almost killed Tesla". Bloomberg L. P. Archived from the original on February 11, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Berger, Eric (2021). Liftoff. William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-06-297997-1.

- ^ Belfiore, Michael (September 1, 2009). "Behind the Scenes With the World's Most Ambitious Rocket Makers". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Podcast: SpaceX COO On Prospects For Starship Launcher Archived June 10, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Aviation Week, Irene Klotz, May 27, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation". SpaceX. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Maney, Kevin (June 17, 2005). "Private sector enticing public into final frontier". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Carl (May 22, 2007). "Elon Musk Is Betting His Fortune on a Mission Beyond Earth's Orbit". Wired. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ "Commercial Market Assessment for Crew and Cargo Systems" (PDF). nasa.gov. NASA. April 27, 2011. p. 40. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

SpaceX has publicly indicated that the development cost for Falcon 9 launch vehicle was approximately $300 million. Additionally, approximately $90 million was spent developing the Falcon 1 launch vehicle which did contribute to some extent to the Falcon 9, for a total of $390 million. NASA has verified these costs.

- ^ Ray, Justin (January 20, 2005). "Cape launch site could host new commercial rocket fleet". spaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2023. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ Berger, Brian (October 3, 2005). "Kistler Teeters on the Brink After Main Investor Withdraws Support". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on April 3, 2024. Retrieved October 7, 2023.

- ^ Belfiore, Michael (January 18, 2005). "Race for Next Space Prize Ignites". Wired. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Berger, Eric (August 11, 2021). "This is probably why Blue Origin keeps protesting NASA's lunar lander award". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "Falcon 1 Reaches Space But Loses Control and is Destroyed on Re-Entry". Satnews.com. March 21, 2007. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Graham Warwick and Guy Norris, "Blue Sky Thinking: DARPA at 50," Aviation Week & Space Technology, Aug 18–25, 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Levin, Steve (January 12, 2022). "Elon Musk, man behind Tesla, Paypal, speaks to packed crowd at CSUB". The Bakersfield Californian. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Graham, William (December 20, 2017). "SpaceX at 50 – From taming Falcon 1 to achieving cadence in Falcon 9". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (January 15, 2009). "Planetspace officially protest NASA's CRS selection". NSF. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ David, Leonard (September 9, 2005). "SpaceX tackles reusable heavy launch vehicle". MSNBC. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: David J. Frankel (April 26, 2010). "Minutes of the NAC Commercial Space Committee" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: David J. Frankel (April 26, 2010). "Minutes of the NAC Commercial Space Committee" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Private space capsule's maiden voyage ends with a splash". BBC News. December 8, 2010. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Chow, Denise (December 8, 2010). "Q & A with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk: Master of Private Space Dragons". Space.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

- ^ Chow, Denise (April 18, 2011). "Private Spaceship Builders Split Nearly $270 Million in NASA Funds". Space.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Koenigsmann, Hans (January 17, 2018). "Statement of Dr. Hans Koeningsmann Vice President, Build and Flight Reliability Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2018.

- ^ Melby, Caleb (March 12, 2012). "How Elon Musk Became A Billionaire Twice Over". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Elon Musk Anticipates Third IPO in Three Years With SpaceX". Bloomberg L. P. February 11, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Watts, Jane (April 27, 2012). "Elon Musk on Why SpaceX Has the Right Stuff to Win the Space Race". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b "Private SpaceX rocket blasts off for space station Cargo ship reaches orbit 9 minutes after launch". CBC News. The Canadian Press. May 22, 2012. Archived from the original on March 13, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Privately-held SpaceX Worth Nearly $2.4 Billion or $20/Share, Double Its Pre-Mission Secondary Market Value Following Historic Success at the International Space Station". privco.com. June 7, 2012. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Bilton, Ricardo (June 10, 2012). "SpaceX's worth skyrockets to $4.8 billion after successful mission". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "SpaceX overview on second market". SecondMarket. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Fernholz, Tim. "The complete visual history of SpaceX's single-minded pursuit of rocket reusability". Quartz. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (January 12, 2015). "Arianespace, SpaceX Battled to a Draw for 2014 Launch Contracts". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Svitak, Amy (February 11, 2014). "Arianespace To ESA: We Need Help". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (April 14, 2014). "Satellite Operators Press ESA for Reduction in Ariane Launch Costs". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Petersen, Melody (November 25, 2014). "SpaceX may upset firm's monopoly in launching Air Force satellites". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Air Force budget reveals how much SpaceX undercuts launch prices". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Berger, Brian (January 20, 2015). "SpaceX Confirms Google Investment". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on February 20, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Kang, Cecilia; Davenport, Christian (June 9, 2015). "SpaceX founder files with government to provide Internet service from space". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Masunaga, Samantha; Petersen, Melody (September 2, 2016). "SpaceX rocket exploded in an instant. Figuring out why involves a mountain of data". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Musk, Elon (December 21, 2015). "Background on tonight's launch". SpaceX. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Wright, Robert (April 9, 2016). "SpaceX rocket lands on drone ship". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ de Selding, Peter B. (October 5, 2016). "SpaceX's Shotwell on Falcon 9 inquiry, discounts for reused rockets and Silicon Valley's test-and-fail ethos". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Santana, Marco (September 6, 2016). "SpaceX customer vows to rebuild satellite in explosion aftermath". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Grush, Loren (November 5, 2016). "Elon Musk says SpaceX finally knows what caused the latest rocket failure". The Verge. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Anomaly Updates". SpaceX. September 1, 2016. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Davenport, Christian (March 30, 2017). "Elon Musk's SpaceX makes history by launching a 'flight-proven' rocket". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ "SpaceX successfully launches, lands a recycled rocket". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ "SpaceX Is Now One of the World's Most Valuable Privately Held Companies". The New York Times. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ "As the SpaceX steamroller surges, European rocket industry vows to resist". July 20, 2018. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ spacexcmsadmin (November 27, 2012). "Company". SpaceX. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Spacexcmsadmin (November 27, 2012). "Company | SpaceX". SpaceX. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Hughes, Tim (July 13, 2017). "Statement of Tim Hughes Senior Vice President for Global Business and Government Affairs Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 23, 2017.

- ^ Agenda Item No. 9, City of Hawthorne City Council, Agenda Bill Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, September 11, 2018, Planning and Community Development Department, City of Hawthorne. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Nelson, Laura J. (November 21, 2017). "Elon Musk's tunneling company wants to dig through L.A." Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Nothing "Boring" About Elon Musk's Newly Revealed Underground Tunnel". cbslocal.com. May 11, 2018. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Copeland, Rob (December 17, 2018). "Elon Musk's New Boring Co. Faced Questions Over SpaceX Financial Ties". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

When the Boring Co. was earlier this year spun into its own firm, more than 90% of the equity went to Mr. Musk and the rest to early employees... The Boring Co. has since given some equity to SpaceX as compensation for the help... about 6% of Boring stock, "based on the value of land, time and other resources contributed since the creation of the company".