Species

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 42 min

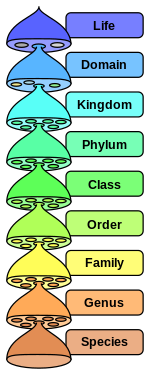

A species (pl. species) is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. Other ways of defining species include their karyotype, DNA sequence, morphology, behaviour, or ecological niche. In addition, palaeontologists use the concept of the chronospecies since fossil reproduction cannot be examined. The most recent rigorous estimate for the total number of species of eukaryotes is between 8 and 8.7 million.[1][2][3] About 14% of these had been described by 2011.[3] All species (except viruses) are given a two-part name, a "binomen". The first part of a binomen is the name of a genus to which the species belongs. The second part is called the specific name or the specific epithet (in botanical nomenclature, also sometimes in zoological nomenclature). For example, Boa constrictor is one of the species of the genus Boa, with constrictor being the specific name.

While the definitions given above may seem adequate at first glance, when looked at more closely they represent problematic species concepts. For example, the boundaries between closely related species become unclear with hybridisation, in a species complex of hundreds of similar microspecies, and in a ring species. Also, among organisms that reproduce only asexually, the concept of a reproductive species breaks down, and each clonal lineage is potentially a microspecies. Although none of these are entirely satisfactory definitions, and while the concept of species may not be a perfect model of life, it is still a useful tool to scientists and conservationists for studying life on Earth, regardless of the theoretical difficulties. If species were fixed and distinct from one another, there would be no problem, but evolutionary processes cause species to change. This obliges taxonomists to decide, for example, when enough change has occurred to declare that a fossil lineage should be divided into multiple chronospecies, or when populations have diverged to have enough distinct character states to be described as cladistic species.

Species and higher taxa were seen from Aristotle until the 18th century as categories that could be arranged in a hierarchy, the great chain of being. In the 19th century, biologists grasped that species could evolve given sufficient time. Charles Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species explained how species could arise by natural selection. That understanding was greatly extended in the 20th century through genetics and population ecology. Genetic variability arises from mutations and recombination, while organisms are mobile, leading to geographical isolation and genetic drift with varying selection pressures. Genes can sometimes be exchanged between species by horizontal gene transfer; new species can arise rapidly through hybridisation and polyploidy; and species may become extinct for a variety of reasons. Viruses are a special case, driven by a balance of mutation and selection, and can be treated as quasispecies.

Definition

[edit]Biologists and taxonomists have made many attempts to define species, beginning from morphology and moving towards genetics. Early taxonomists such as Linnaeus had no option but to describe what they saw: this was later formalised as the typological or morphological species concept. Ernst Mayr emphasised reproductive isolation, but this, like other species concepts, can be hard or even impossible to test for groups of organisms separated in space or time.[4][5] Later biologists have tried to refine Mayr's definition with the recognition and cohesion concepts, among others.[6] Many of the concepts are quite similar or overlap, so they are not easy to count: the biologist R. L. Mayden recorded about 24 concepts,[7] and the philosopher of science John Wilkins counted 26.[4] Wilkins further grouped the species concepts into seven basic kinds of concepts: (1) agamospecies for asexual organisms (2) biospecies for reproductively isolated sexual organisms (3) ecospecies based on ecological niches (4) evolutionary species based on lineage (5) genetic species based on gene pool (6) morphospecies based on form or phenotype and (7) taxonomic species, a species as determined by a taxonomist.[8]

Typological or morphological species

[edit]

A typological species is a group of organisms in which individuals conform to certain fixed properties (a type, which may be defined by a chosen 'nominal species'), so that even pre-literate people often recognise the same taxon as do modern taxonomists.[10][11] Modern-day field guides and identification websites such as iNaturalist use this concept. The clusters of variations or phenotypes within specimens (such as longer or shorter tails) would differentiate the species. This method was used as a "classical" method of determining species, such as with Linnaeus, early in evolutionary theory. However, different phenotypes are not necessarily different species (e.g. a four-winged Drosophila born to a two-winged mother is not a different species). Species named in this manner are called morphospecies.[12][13]

In the 1970s, Robert R. Sokal, Theodore J. Crovello and Peter Sneath proposed a variation on the morphological species concept, a phenetic species, defined as a set of organisms with a similar phenotype to each other, but a different phenotype from other sets of organisms.[14] It differs from the morphological species concept in including a numerical measure of distance or similarity to cluster entities based on multivariate comparisons of a reasonably large number of phenotypic traits.[15]

Recognition and cohesion species

[edit]A mate-recognition species is a group of sexually reproducing organisms that recognise one another as potential mates.[16][17] Expanding on this to allow for post-mating isolation, a cohesion species is the most inclusive population of individuals having the potential for phenotypic cohesion through intrinsic cohesion mechanisms; no matter whether populations can hybridise successfully, they are still distinct cohesion species if the amount of hybridisation is insufficient to completely mix their respective gene pools.[18] A further development of the recognition concept is provided by the biosemiotic concept of species.[19]

Genetic similarity and barcode species

[edit]

Single locus (barcoding)

[edit]In microbiology, genes can move freely even between distantly related bacteria, possibly extending to the whole bacterial domain. As a rule of thumb, microbiologists had assumed that members of Bacteria or Archaea with 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences more similar than 97% to each other need to be checked by DNA–DNA hybridisation to decide if they belong to the same species.[20] This concept was narrowed in 2006 to a similarity of 98.7%.[21]

The 16S sequence is an example of a single locus which is simple enough for non-specialists to apply and, in most cases, sufficient to distinguish species. Using a single easy-to-use locus to distinguish taxa is called DNA barcoding.[22] One of the barcodes for eukaryotes is a region of mitochondrial DNA within the gene for cytochrome c oxidase. A database, Barcode of Life Data System, contains DNA barcode sequences from over 190,000 species.[23][24] However, scientists such as Rob DeSalle have expressed concern that classical taxonomy and DNA barcoding, which they consider a misnomer, need to be reconciled, as they delimit species differently.[25] Genetic introgression mediated by endosymbionts and other vectors can further make barcodes ineffective in the identification of species.[26]

A singular locus can be a good proxy of time of divergence assuming the chosen locus evolved like most of the rest of the genome. This assumption can be broken by horizontal gene transfer affecting the locus itself. Rapid modes of evolution separating biological species (speciation) over a short timespan would also decouple the species concept from time itself. Among bacteria, there are several cases where very different genomes share 99.9% 16S identity.[27]

Multilocus comparison

[edit]Using multiple (usually fewer than 10) loci for comparison provides more phylogenetic signal compared to comparing versions of the same loci as more mutations can be captured. As a result, it provides improved taxonomic resolution compared to single-locus comparison, giving results more similar to the expensive "gold standard" of whole genome comparison at a small increase in cost.[28]

Even when whole genomes are available, there are good reasons to only compare select genes: many genes are not universally found in all genomes, so they provide limited taxonomic signal while still adding to the computational cost of comparison. In situations like this, tens to hundreds of loci may be extracted from each genome and used together. As with comparisons with fewer loci, marker genes used for this purpose should be genes with low rates of horizontal transfer and gene duplication, few known instances of horizontal transfer, and high occurrence in the sampled genomes.[29][30] With prokaryotes, marker genes can be used to delimit taxa down to the genus level, with whole-genome comparison reserved to separate species from each other.[31]

Whole genome comparison

[edit]The surefire way to capture all gene flow among populations is to compare their entire genomes. The average nucleotide identity (ANI) method quantifies genetic distance between entire genomes, using regions of about 10,000 base pairs. With enough data from genomes of one genus, algorithms can be used to categorize species, as for Pseudomonas avellanae in 2013,[32] and for all sequenced bacteria and archaea since 2020.[33] Observed ANI values among prokaryotic sequences appear to have an "ANI gap" at 85–95%, suggesting that a genetic boundary suitable for defining a species concept is present.[34]

Phylogenetic or cladistic species

[edit]

A phylogenetic or cladistic species is "the smallest aggregation of populations (sexual) or lineages (asexual) diagnosable by a unique combination of character states in comparable individuals (semaphoronts)".[35] The empirical basis – observed character states – provides the evidence to support hypotheses about evolutionarily divergent lineages that have maintained their hereditary integrity through time and space.[36][37][38][39] Molecular markers may be used to determine diagnostic genetic differences in the nuclear or mitochondrial DNA of various species.[40][35][41] For example, in a study done on fungi, studying the nucleotide characters using cladistic species produced the most accurate results in recognising the numerous fungi species of all the concepts studied.[41][42] Versions of the phylogenetic species concept that emphasise monophyly or diagnosability[43] may lead to splitting of existing species, for example in Bovidae, by recognising old subspecies as species, despite the fact that there are no reproductive barriers, and populations may intergrade morphologically.[44] Others have called this approach taxonomic inflation, diluting the species concept and making taxonomy unstable.[45] Yet others defend this approach, considering "taxonomic inflation" pejorative and labelling the opposing view as "taxonomic conservatism"; claiming it is politically expedient to split species and recognise smaller populations at the species level, because this means they can more easily be included as endangered in the IUCN red list and can attract conservation legislation and funding.[46]

Unlike the biological species concept, a cladistic species does not rely on reproductive isolation – its criteria are independent of processes that are integral in other concepts.[35] Therefore, it applies to asexual lineages.[40][41] However, it does not always provide clear cut and intuitively satisfying boundaries between taxa, and may require multiple sources of evidence, such as more than one polymorphic locus, to give plausible results.[41]

Evolutionary species

[edit]An evolutionary species, suggested by George Gaylord Simpson in 1951, is "an entity composed of organisms which maintains its identity from other such entities through time and over space, and which has its own independent evolutionary fate and historical tendencies".[7][47] This differs from the biological species concept in embodying persistence over time. Wiley and Mayden stated that they see the evolutionary species concept as "identical" to Willi Hennig's species-as-lineages concept, and asserted that the biological species concept, "the several versions" of the phylogenetic species concept, and the idea that species are of the same kind as higher taxa are not suitable for biodiversity studies (with the intention of estimating the number of species accurately). They further suggested that the concept works for both asexual and sexually-reproducing species.[48] A version of the concept is Kevin de Queiroz's "General Lineage Concept of Species".[49]

Ecological species

[edit]An ecological species is a set of organisms adapted to a particular set of resources, called a niche, in the environment. According to this concept, populations form the discrete phenetic clusters that we recognise as species because the ecological and evolutionary processes controlling how resources are divided up tend to produce those clusters.[50]

Genetic species

[edit]A genetic species as defined by Robert Baker and Robert Bradley is a set of genetically isolated interbreeding populations. This is similar to Mayr's Biological Species Concept, but stresses genetic rather than reproductive isolation.[51] In the 21st century, a genetic species could be established by comparing DNA sequences. Earlier, other methods were available, such as comparing karyotypes (sets of chromosomes) and allozymes (enzyme variants).[52]

Evolutionarily significant unit

[edit]An evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) or "wildlife species"[53] is a population of organisms considered distinct for purposes of conservation.[54]

Chronospecies

[edit]

In palaeontology, with only comparative anatomy (morphology) and histology[55] from fossils as evidence, the concept of a chronospecies can be applied. During anagenesis (evolution, not necessarily involving branching), some palaeontologists seek to identify a sequence of species, each one derived from the phyletically extinct one before through continuous, slow and more or less uniform change. In such a time sequence, some palaeontologists assess how much change is required for a morphologically distinct form to be considered a different species from its ancestors.[56][57][58][59]

Viral quasispecies

[edit]Viruses have enormous populations, are doubtfully living since they consist of little more than a string of DNA or RNA in a protein coat, and mutate rapidly. All of these factors make conventional species concepts largely inapplicable.[60] A viral quasispecies is a group of genotypes related by similar mutations, competing within a highly mutagenic environment, and hence governed by a mutation–selection balance. It is predicted that a viral quasispecies at a low but evolutionarily neutral and highly connected (that is, flat) region in the fitness landscape will outcompete a quasispecies located at a higher but narrower fitness peak in which the surrounding mutants are unfit, "the quasispecies effect" or the "survival of the flattest". There is no suggestion that a viral quasispecies resembles a traditional biological species.[61][62][63] The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses has since 1962 developed a universal taxonomic scheme for viruses; this has stabilised viral taxonomy.[64][65][66]

Mayr's biological species concept

[edit]

Most modern textbooks make use of Ernst Mayr's 1942 definition,[67][68] known as the biological species concept, as a basis for further discussion on the definition of species. It is also called a reproductive or isolation concept. This defines a species as[69]

groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, which are reproductively isolated from other such groups.[69]

It has been argued that this definition is a natural consequence of the effect of sexual reproduction on the dynamics of natural selection.[70][71][72][73] Mayr's use of the adjective "potentially" has been a point of debate; some interpretations exclude unusual or artificial matings that occur only in captivity, or that involve animals capable of mating but that do not normally do so in the wild.[69]

The species problem

[edit]It is difficult to define a species in a way that applies to all organisms.[74] This debate about species concepts is called the species problem.[69][75][76][77] The problem was recognised even in 1859, when Darwin wrote in On the Origin of Species:

I was much struck how entirely vague and arbitrary is the distinction between species and varieties.[78]

He went on to write:

No one definition has satisfied all naturalists; yet every naturalist knows vaguely what he means when he speaks of a species. Generally the term includes the unknown element of a distinct act of creation.[79]

Problems with simple definitions of species

[edit]

Many authors have argued that a simple textbook definition, following Mayr's concept, works well for most multi-celled organisms, but breaks down in several situations:

- When organisms reproduce asexually, as in single-celled organisms such as bacteria and other prokaryotes,[80] and parthenogenetic or apomictic multi-celled organisms. DNA barcoding and phylogenetics are commonly used in these cases.[81][82][83] The term quasispecies is sometimes used for rapidly mutating entities like viruses.[84][85]

- When scientists do not know whether two morphologically similar groups of organisms are capable of interbreeding; this is the case with all extinct life-forms in palaeontology, as breeding experiments are not possible.[86]

- When hybridisation permits substantial gene flow between species.[87]

- In ring species, when members of adjacent populations in a widely continuous distribution range interbreed successfully but members of more distant populations do not.[88]

Species identification is made difficult by discordance between molecular and morphological investigations; these can be categorised as two types: (i) one morphology, multiple lineages (e.g. morphological convergence, cryptic species) and (ii) one lineage, multiple morphologies (e.g. phenotypic plasticity, multiple life-cycle stages).[89] In addition, horizontal gene transfer (HGT) makes it difficult to define a species.[90] All species definitions assume that an organism acquires its genes from one or two parents very like the "daughter" organism, but that is not what happens in HGT.[91] There is strong evidence of HGT between very dissimilar groups of prokaryotes, and at least occasionally between dissimilar groups of eukaryotes,[90] including some crustaceans and echinoderms.[92]

The evolutionary biologist James Mallet concludes that

there is no easy way to tell whether related geographic or temporal forms belong to the same or different species. Species gaps can be verified only locally and at a point of time. One is forced to admit that Darwin's insight is correct: any local reality or integrity of species is greatly reduced over large geographic ranges and time periods.[18]

The botanist Brent Mishler[93] argued that the species concept is not valid, notably because gene flux decreases gradually rather than in discrete steps, which hampers objective delimitation of species.[94] Indeed, complex and unstable patterns of gene flux have been observed in cichlid teleosts of the East African Great Lakes.[95] Wilkins argued that "if we were being true to evolution and the consequent phylogenetic approach to taxa, we should replace it with a 'smallest clade' idea" (a phylogenetic species concept).[96] Mishler and Wilkins[97] and others[98] concur with this approach, even though this would raise difficulties in biological nomenclature. Wilkins cited the ichthyologist Charles Tate Regan's early 20th century remark that "a species is whatever a suitably qualified biologist chooses to call a species".[96] Wilkins noted that the philosopher Philip Kitcher called this the "cynical species concept",[99] and arguing that far from being cynical, it usefully leads to an empirical taxonomy for any given group, based on taxonomists' experience.[96] Other biologists have gone further and argued that we should abandon species entirely, and refer to the "Least Inclusive Taxonomic Units" (LITUs),[100] a view that would be coherent with current evolutionary theory.[98]

Aggregates of microspecies

[edit]The species concept is further weakened by the existence of microspecies, groups of organisms, including many plants, with very little genetic variability, usually forming species aggregates.[101] For example, the dandelion Taraxacum officinale and the blackberry Rubus fruticosus are aggregates with many microspecies—perhaps 400 in the case of the blackberry and over 200 in the dandelion in Britain alone,[102] complicated by hybridisation, apomixis and polyploidy, making gene flow between populations difficult to determine, and their taxonomy debatable.[103][104][105] Species complexes occur in insects such as Heliconius butterflies,[106] vertebrates such as Hypsiboas treefrogs,[107] and fungi such as the fly agaric.[108]

-

Blackberries belong to any of hundreds of microspecies of the Rubus fruticosus species aggregate.

-

The butterfly genus Heliconius contains many similar species.

-

The Hypsiboas calcaratus–fasciatus species complex contains at least six species of treefrog.

Hybridisation

[edit]Natural hybridisation presents a challenge to the concept of a reproductively isolated species, as fertile hybrids permit gene flow between two populations. For example, the carrion crow Corvus corone and the hooded crow Corvus cornix appear and are classified as separate species, yet they can hybridise where their geographical ranges overlap.[109]

- Hybridisation of carrion and hooded crows permits gene flow between 'species'

-

Hybrid with dark belly

Ring species

[edit]A ring species is a connected series of neighbouring populations, each of which can sexually interbreed with adjacent related populations, but for which there exist at least two "end" populations in the series, which are too distantly related to interbreed, though there is a potential gene flow between each "linked" population.[110] Such non-breeding, though genetically connected, "end" populations may co-exist in the same region thus closing the ring. Ring species thus present a difficulty for any species concept that relies on reproductive isolation.[111] However, ring species are at best rare. Proposed examples include the herring gull–lesser black-backed gull complex around the North pole, the Ensatina eschscholtzii group of 19 populations of salamanders in America,[112] and the greenish warbler in Asia,[113] but many so-called ring species have turned out to be the result of misclassification leading to questions on whether there really are any ring species.[114][115][116][117]

-

Seven "species" of Larus gulls interbreed in a ring around the Arctic.

-

Opposite ends of the ring: a herring gull (Larus argentatus) (front) and a lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) in Norway

-

A greenish warbler, Phylloscopus trochiloides

Taxonomy and naming

[edit]

Common and scientific names

[edit]The commonly used names for kinds of organisms are often ambiguous: "cat" could mean the domestic cat, Felis catus, or the cat family, Felidae. Another problem with common names is that they often vary from place to place, so that puma, cougar, catamount, panther, painter and mountain lion all mean Puma concolor in various parts of America, while "panther" may also mean the jaguar (Panthera onca) of Latin America or the leopard (Panthera pardus) of Africa and Asia. In contrast, the scientific names of species are chosen to be unique and universal (except for some inter-code homonyms); they are in two parts used together: the genus as in Puma, and the specific epithet as in concolor.[118][119]

Species description

[edit]

A species is given a taxonomic name when a type specimen is described formally, in a publication that assigns it a unique scientific name. The description typically provides means for identifying the new species, which may not be based solely on morphology[120] (see cryptic species), differentiating it from other previously described and related or confusable species and provides a validly published name (in botany) or an available name (in zoology) when the paper is accepted for publication. The type material is usually held in a permanent repository, often the research collection of a major museum or university, that allows independent verification and the means to compare specimens.[121][122][123] Describers of new species are asked to choose names that, in the words of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, are "appropriate, compact, euphonious, memorable, and do not cause offence".[124]

Abbreviations

[edit]Books and articles sometimes intentionally do not identify species fully, using the abbreviation "sp." in the singular or "spp." (standing for species pluralis, Latin for "multiple species") in the plural in place of the specific name or epithet (e.g. "Canis sp."). This commonly occurs when authors are confident that some individuals belong to a particular genus but are not sure to which exact species they belong, as is common in paleontology.[125]

Authors may also use "spp." as a short way of saying that something applies to many species within a genus, but not to all. If scientists mean that something applies to all species within a genus, they use the genus name without the specific name or epithet. The names of genera and species are usually printed in italics. However, abbreviations such as "sp." should not be italicised.[125]

When a species' identity is not clear, a specialist may use "cf." before the epithet to indicate that confirmation is required. The abbreviations "nr." (near) or "aff." (affine) may be used when the identity is unclear but when the species appears to be similar to the species mentioned after.[125]

Identification codes

[edit]With the rise of online databases, codes have been devised to provide identifiers for species that are already defined, including:

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) employs a numeric 'taxid' or Taxonomy identifier, a "stable unique identifier", e.g., the taxid of Homo sapiens is 9606.[126]

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) employs a three- or four-letter code for a limited number of organisms; in this code, for example, H. sapiens is simply hsa.[127]

- UniProt employs an "organism mnemonic" of not more than five alphanumeric characters, e.g., HUMAN for H. sapiens.[128]

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) provides a unique number for each species. The LSID for Homo sapiens is urn:lsid:catalogueoflife.org:taxon:4da6736d-d35f-11e6-9d3f-bc764e092680:col20170225.[129]

Lumping and splitting

[edit]The naming of a particular species, including which genus (and higher taxa) it is placed in, is a hypothesis about the evolutionary relationships and distinguishability of that group of organisms. As further information comes to hand, the hypothesis may be corroborated or refuted. Sometimes, especially in the past when communication was more difficult, taxonomists working in isolation have given two distinct names to individual organisms later identified as the same species. When two species names are discovered to apply to the same species, the older species name is given priority and usually retained, and the newer name considered as a junior synonym, a process called synonymy. Dividing a taxon into multiple, often new, taxa is called splitting. Taxonomists are often referred to as "lumpers" or "splitters" by their colleagues, depending on their personal approach to recognising differences or commonalities between organisms.[130][131][125] The circumscription of taxa, considered a taxonomic decision at the discretion of cognizant specialists, is not governed by the Codes of Zoological or Botanical Nomenclature, in contrast to the PhyloCode, and contrary to what is done in several other fields, in which the definitions of technical terms, like geochronological units and geopolitical entities, are explicitly delimited.[132][98]

Broad and narrow senses

[edit]The nomenclatural codes that guide the naming of species, including the ICZN for animals and the ICN for plants, do not make rules for defining the boundaries of the species. Research can change the boundaries, also known as circumscription, based on new evidence. Species may then need to be distinguished by the boundary definitions used, and in such cases the names may be qualified with sensu stricto ("in the narrow sense") to denote usage in the exact meaning given by an author such as the person who named the species, while the antonym sensu lato ("in the broad sense") denotes a wider usage, for instance including other subspecies. Other abbreviations such as "auct." ("author"), and qualifiers such as "non" ("not") may be used to further clarify the sense in which the specified authors delineated or described the species.[125][133][134]

Change

[edit]Species are subject to change, whether by evolving into new species,[135] exchanging genes with other species,[136] merging with other species or by becoming extinct.[137]

Speciation

[edit]The evolutionary process by which biological populations of sexually-reproducing organisms evolve to become distinct or reproductively isolated as species is called speciation.[138][139] Charles Darwin was the first to describe the role of natural selection in speciation in his 1859 book The Origin of Species.[140] Speciation depends on a measure of reproductive isolation, a reduced gene flow. This occurs most easily in allopatric speciation, where populations are separated geographically and can diverge gradually as mutations accumulate. Reproductive isolation is threatened by hybridisation, but this can be selected against once a pair of populations have incompatible alleles of the same gene, as described in the Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller model.[135] A different mechanism, phyletic speciation, involves one lineage gradually changing over time into a new and distinct form (a chronospecies), without increasing the number of resultant species.[141]

Exchange of genes between species

[edit]

Horizontal gene transfer between organisms of different species, either through hybridisation, antigenic shift, or reassortment, is sometimes an important source of genetic variation. Viruses can transfer genes between species. Bacteria can exchange plasmids with bacteria of other species, including some apparently distantly related ones in different phylogenetic domains, making analysis of their relationships difficult, and weakening the concept of a bacterial species.[142][90][143][136]

Louis-Marie Bobay and Howard Ochman suggest, based on analysis of the genomes of many types of bacteria, that they can often be grouped "into communities that regularly swap genes", in much the same way that plants and animals can be grouped into reproductively isolated breeding populations. Bacteria may thus form species, analogous to Mayr's biological species concept, consisting of asexually reproducing populations that exchange genes by homologous recombination.[144][145]

Extinction

[edit]A species is extinct when the last individual of that species dies, but it may be functionally extinct well before that moment. It is estimated that over 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth, some five billion species, are now extinct. Some of these were in mass extinctions such as those at the ends of the Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic and Cretaceous periods. Mass extinctions had a variety of causes including volcanic activity, climate change, and changes in oceanic and atmospheric chemistry, and they in turn had major effects on Earth's ecology, atmosphere, land surface and waters.[146][147] Another form of extinction is through the assimilation of one species by another through hybridization. The resulting single species has been termed as a "compilospecies".[148]

Practical implications

[edit]Biologists and conservationists need to categorise and identify organisms in the course of their work. Difficulty assigning organisms reliably to a species constitutes a threat to the validity of research results, for example making measurements of how abundant a species is in an ecosystem moot. Surveys using a phylogenetic species concept reported 48% more species and accordingly smaller populations and ranges than those using nonphylogenetic concepts; this was termed "taxonomic inflation",[149] which could cause a false appearance of change to the number of endangered species and consequent political and practical difficulties.[150][151] Some observers claim that there is an inherent conflict between the desire to understand the processes of speciation and the need to identify and to categorise.[151]

Conservation laws in many countries make special provisions to prevent species from going extinct. Hybridization zones between two species, one that is protected and one that is not, have sometimes led to conflicts between lawmakers, land owners and conservationists. One of the classic cases in North America is that of the protected northern spotted owl which hybridises with the unprotected California spotted owl and the barred owl; this has led to legal debates.[152]

It has been argued, that since species are not comparable, simply counting them is not a valid measure of biodiversity; alternative measures of phylogenetic biodiversity have been proposed.[153][94][154]

History

[edit]Classical forms

[edit]In his biology, Aristotle used the term γένος (génos) to mean a kind, such as a bird or fish, and εἶδος (eidos) to mean a specific form within a kind, such as (within the birds) the crane, eagle, crow, or sparrow. These terms were translated into Latin as "genus" and "species", though they do not correspond to the Linnean terms thus named; today the birds are a class, the cranes are a family, and the crows a genus. A kind was distinguished by its attributes; for instance, a bird has feathers, a beak, wings, a hard-shelled egg, and warm blood. A form was distinguished by being shared by all its members, the young inheriting any variations they might have from their parents. Aristotle believed all kinds and forms to be distinct and unchanging. More importantly, in Aristotle's works, the terms γένος (génos) and εἶδος (eidos) are relative; a taxon that is considered an eidos in a given context can be considered a génos in another, and be further subdivided into eide (plural of eidos).[155][156] His approach remained influential until the Renaissance,[157] and still, to a lower extent, today.[158]

Fixed species

[edit]

When observers in the Early Modern period began to develop systems of organization for living things, they placed each kind of animal or plant into a context. Many of these early delineation schemes would now be considered whimsical: schemes included consanguinity based on colour (all plants with yellow flowers) or behaviour (snakes, scorpions and certain biting ants). John Ray, an English naturalist, was the first to attempt a biological definition of species in 1686, as follows:

No surer criterion for determining species has occurred to me than the distinguishing features that perpetuate themselves in propagation from seed. Thus, no matter what variations occur in the individuals or the species, if they spring from the seed of one and the same plant, they are accidental variations and not such as to distinguish a species ... Animals likewise that differ specifically preserve their distinct species permanently; one species never springs from the seed of another nor vice versa.[159]

In the 18th century, the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus classified organisms according to shared physical characteristics, and not simply based upon differences.[160] Like many contemporary systematists,[161][162][163] he established the idea of a taxonomic hierarchy of classification based upon observable characteristics and intended to reflect natural relationships.[164][165] At the time, however, it was still widely believed that there was no organic connection between species (except, possibly, between those of a given genus),[98] no matter how similar they appeared. This view was influenced by European scholarly and religious education, which held that the taxa had been created by God, forming an Aristotelian hierarchy, the scala naturae or great chain of being. However, whether or not it was supposed to be fixed, the scala (a ladder) inherently implied the possibility of climbing.[166]

Mutability

[edit]In viewing evidence of hybridisation, Linnaeus recognised that species were not fixed and could change; he did not consider that new species could emerge and maintained a view of divinely fixed species that may alter through processes of hybridisation or acclimatisation.[167] By the 19th century, naturalists understood that species could change form over time, and that the history of the planet provided enough time for major changes. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, in his 1809 Zoological Philosophy, described the transmutation of species, proposing that a species could change over time, in a radical departure from Aristotelian thinking.[168]

In 1858, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace provided a compelling account of evolution and the formation of new species.[1] Darwin argued that it was populations that evolved, not individuals, by natural selection from naturally occurring variation among individuals.[169] This required a new definition of species. Darwin concluded that species are what they appear to be: ideas, provisionally useful for naming groups of interacting individuals, writing:

I look at the term species as one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other ... It does not essentially differ from the word variety, which is given to less distinct and more fluctuating forms. The term variety, again, in comparison with mere individual differences, is also applied arbitrarily, and for convenience sake.[170]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wilson, Edward O. (3 March 2018). "Opinion: The 8 Million Species We Don't Know". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Borenstein, S. (2019). "UN report: Humans accelerating extinction of other species". Associated Press.

- ^ a b Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Worm, Boris (23 August 2011). "How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?". PLOS Biology. 9 (8): e1001127. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. PMC 3160336. PMID 21886479.

- ^ a b "Species Concepts". Scientific American. 20 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Mallet, James (1995). "A species definition for the modern synthesis". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 10 (7): 294–299. Bibcode:1995TEcoE..10..294M. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(95)90031-4. PMID 21237047.

- ^ Masters, J. C.; Spencer, H. G. (1989). "Why We Need a New Genetic Species Concept". Systematic Zoology. 38 (3): 270–279. doi:10.2307/2992287. JSTOR 2992287.

- ^ a b Mayden, R. L. (1997). "A hierarchy of species concepts: the denouement of the species problem". In Claridge, M. F.; Dawah, H. A.; Wilson, M. R. (eds.). The Units of Biodiversity – Species in Practice Special Volume 54. Systematics Association.

- ^ Zachos 2016, p. 79.

- ^ Gooders, John (1986). Kingfisher Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland. Kingfisher Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-86272-139-8.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). "A Quahog is a Quahog". In: The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 204–213. ISBN 978-0-393-30023-9.

- ^ Maynard Smith, John (1989). Evolutionary Genetics. Oxford University Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-19-854215-5.

- ^ Ruse, Michael (1969). "Definitions of Species in Biology". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 20 (2): 97–119. doi:10.1093/bjps/20.2.97. JSTOR 686173. S2CID 121580839.

- ^ Lewin, Ralph A. (1981). "Three Species Concepts". Taxon. 30 (3): 609–613. Bibcode:1981Taxon..30..609L. doi:10.2307/1219942. JSTOR 1219942.

- ^ Claridge, Dawah & Wilson 1997, p. 404

- ^ Ghiselin, Michael T. (1974). "A Radical Solution to the Species Problem". Systematic Biology. 23 (4): 536–544. doi:10.1093/sysbio/23.4.536.

- ^ Claridge et al.:408–409.

- ^ Paterson, H. E. H. (1985). "Species and Speciation". In Vrba, E. S. (ed.). Monograph No. 4: The recognition concept of species. Pretoria: Transvaal Museum.

- ^ a b Mallet, James (28 September 1999). "Species, Concepts of" (PDF). In Calow, P. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Ecology and Environmental Management. Blackwell. pp. 709–711. ISBN 978-0-632-05546-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2016.

- ^ Kull, Kalevi (2016). "The biosemiotic concept of the species". Biosemiotics. 9: 61–71. doi:10.1007/s12304-016-9259-2. S2CID 18470078. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018.

- ^ Stackebrandt, E.; Goebel, B. M. (1994). "Taxonomic note: a place for DNA–DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 44 (4): 846–849. doi:10.1099/00207713-44-4-846.

- ^ Stackebrandt, E.; Ebers, J. (2006). "Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards" (PDF). Microbiology Today. 33 (4): 152–155. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2018.

- ^ "What Is DNA Barcoding?". Barcode of Life. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Ratnasingham, Sujeevan; Hebert, Paul D. N. (2007). "BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System". Molecular Ecology Notes. 7 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x. PMC 1890991. PMID 18784790.

- ^ Stoeckle, Mark (November–December 2013). "DNA Barcoding Ready for Breakout". GeneWatch. 26 (5). Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ DeSalle, R.; Egan, M. G.; Siddall, M. (2005). "The unholy trinity: taxonomy, species delimitation and DNA barcoding". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 360 (1462): 1905–1916. doi:10.1098/rstb.2005.1722. PMC 1609226. PMID 16214748.

- ^ Whitworth, T. L.; Dawson, R. D.; Magalon, H.; Baudry, E. (2007). "DNA barcoding cannot reliably identify species of the blowfly genus Protocalliphora (Diptera: Calliphoridae)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1619): 1731–1739. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0062. PMC 2493573. PMID 17472911.

- ^ Bartoš, Oldřich; Chmel, Martin; Swierczková, Iva (20 April 2024). "The overlooked evolutionary dynamics of 16S rRNA revises its role as the "gold standard" for bacterial species identification". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 9067. Bibcode:2024NatSR..14.9067B. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59667-3. PMC 11032355. PMID 38643216.

- ^ Vargas Ribera, Pablo Roberto; Kim, Nuri; Venbrux, Marc; Álvarez-Pérez, Sergio; Rediers, Hans (19 November 2024). "Evaluation of sequence-based tools to gather more insight into the positioning of rhizogenic agrobacteria within the Agrobacterium tumefaciens species complex". PLOS ONE. 19 (11): e0302954. Bibcode:2024PLoSO..1902954V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0302954. PMC 11575935. PMID 39561304.

- ^ Manni, Mosè; Berkeley, Matthew R.; Seppey, Mathieu; Zdobnov, Evgeny M. (December 2021). "BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond". Current Protocols. 1 (12). doi:10.1002/cpz1.323. PMID 34936221.

- ^ Sussfeld, D; Lannes, R; Corel, E; Bernard, G; Martin, P; Bapteste, E; Pelletier, E; Lopez, P (11 June 2025). "New groups of highly divergent proteins in families as old as cellular life with important biological functions in the ocean". Environmental Microbiome. 20 (1): 65. doi:10.1186/s40793-025-00697-3. PMC 12153180. PMID 40500757.

- ^ Parks, DH; Chuvochina, M; Rinke, C; Mussig, AJ; Chaumeil, PA; Hugenholtz, P (7 January 2022). "GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy". Nucleic Acids Research. 50 (D1): D785 – D794. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab776. PMC 8728215. PMID 34520557.

- ^ Land, Miriam; Hauser, Loren; Jun, Se-Ran; Nookaew, Intawat; Leuze, Michael R.; Ahn, Tae-Hyuk; Karpinets, Tatiana; Lund, Ole; Kora, Guruprased; Wassenaar, Trudy; Poudel, Suresh; Ussery, David W. (2015). "Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing". Functional & Integrative Genomics. 15 (2): 141–161. doi:10.1007/s10142-015-0433-4. PMC 4361730. PMID 25722247.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine license.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Archived 16 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine license.

- ^ Parks, D. H.; Chuvochina, M.; Chaumeil, P. A.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A. J.; Hugenholtz, P. (September 2020). "A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (9): 1079–1086. bioRxiv 10.1101/771964. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0501-8. PMID 32341564. S2CID 216560589.

- ^ Rodriguez-R, Luis M.; Jain, Chirag; Conrad, Roth E.; Aluru, Srinivas; Konstantinidis, Konstantinos T. (7 July 2021). "Reply to: "Re-evaluating the evidence for a universal genetic boundary among microbial species"". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4060. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4060R. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24129-1. PMC 8263725. PMID 34234115.

- ^ a b c Nixon, K. C.; Wheeler, Q. D. (1990). "An amplification of the phylogenetic species concept". Cladistics. 6 (3): 211–223. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1990.tb00541.x. S2CID 84095773.

- ^ Wheeler, Quentin D.; Platnick, Norman I. 2000. The phylogenetic species concept (sensu Wheeler & Platnick). In: Wheeler & Meier2000, pp. 55–69

- ^ Giraud, T.; Refrégier, G.; Le Gac, M.; de Vienne, D. M.; Hood, M. E. (2008). "Speciation in Fungi". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 45 (6): 791–802. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.02.001. PMID 18346919.

- ^ Bernardo, J. (2011). "A critical appraisal of the meaning and diagnosability of cryptic evolutionary diversity, and its implications for conservation in the face of climate change". In Hodkinson, T.; Jones, M.; Waldren, S.; Parnell, J. (eds.). Climate Change, Ecology and Systematics. Systematics Association Special Series. Cambridge University Press. pp. 380–438. ISBN 978-0-521-76609-8..

- ^ Brower, Andrew V. Z. and Randall T. Schuh. (2021). Biological Systematics: Principles and Applications. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

- ^ a b Giraud, T.; Refrégier, G.; Le Gac, M.; de Vienne, D. M.; Hood, M. E. (2008). "Speciation in Fungi". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 45 (6): 791–802. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2008.02.001. PMID 18346919.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, J. W.; Jacobson, D. J.; Kroken, S.; Kasuga, T.; Geiser, D. M.; Hibbett, D. S.; Fisher, M. C. (2000). "Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 31 (1): 21–32. doi:10.1006/fgbi.2000.1228. PMID 11118132. S2CID 2551424.

- ^ Taylor, J. W.; Turner, E.; Townsend, J. P.; Dettman, J. R.; Jacobson, D. (2006). "Eukaryotic microbes, species recognition and the geographic limits of species: Examples from the kingdom Fungi". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 361 (1475): 1947–1963. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1923. PMC 1764934. PMID 17062413.

- ^ Zachos 2016, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Groves, C.; Grubb, P. 2011. Ungulate taxonomy. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Heller, R.; Frandsen, P.; Lorenzen, E. D.; Siegismund, H. R. (2013). "Are there really twice as many bovid species as we thought?". Systematic Biology. 62 (3): 490–493. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syt004. hdl:10400.7/566. PMID 23362112.

- ^ Cotterill, F.; Taylor, P.; Gippoliti, S.; et al. (2014). "Why one century of phenetics is enough: Response to 'are there really twice as many bovid species as we thought?'". Systematic Biology. 63 (5): 819–832. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu003. PMID 24415680.

- ^ Laporte, L. O. F. (1994). "Simpson on species". Journal of the History of Biology. 27 (1): 141–159. doi:10.1007/BF01058629. PMID 11639257. S2CID 34975382.

- ^ Wheeler & Meier 2000, pp. 70–92, 146–160, 198–208

- ^ de Queiroz, Kevin (1998). "The general lineage concept of species, species criteria, and the process of speciation". In D. J. Howard; S. H. Berlocher (eds.). Endless forms: species and speciation. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–75.

- ^ Ridley, Mark. "The Idea of Species". Evolution (2nd ed.). Blackwell Science. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-86542-495-1.

- ^ Baker, Robert J.; Bradley, Robert D. (2006). "Speciation in Mammals and the Genetic Species Concept". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (4): 643–662. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-F-038R2.1. PMC 2771874. PMID 19890476.

- ^ Baker, Robert J.; Bradley, Robert D. (2006). "Speciation in Mammals and the Genetic Species Concept". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (4): 643–662. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-F-038R2.1. PMC 2771874. PMID 19890476.

- ^ Government of Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. "COSEWIC's Assessment Process and Criteria". Cosepac.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ DeWeerdt, Sarah (29 July 2002). "What Really is an Evolutionarily Significant Unit?". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ de Buffrénil, Vivian; de Ricqlès, Armand J; Zylberberg, Louise; Padian, Kevin; Laurin, Michel; Quilhac, Alexandra (2021). Vertebrate skeletal histology and paleohistology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. xii + 825. ISBN 978-1-351-18957-6.

- ^ "Chronospecies". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Carr, Steven M. (2005). "Evolutionary species and chronospecies". Memorial University Newfoundland and Labrador. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Dzik, J. (1985). "Typologic versus population concepts of chronospecies: implications for ammonite biostratigraphy" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 30 (1–2): 71–92. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ O'Brien, Michael J.; Lyman, R. Lee (2007). Applying Evolutionary Archaeology: A Systematic Approach. Springer. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-0-306-47468-2. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018.

- ^ Van Regenmortel, Marc H. V. (2010). "Logical puzzles and scientific controversies: The nature of species, viruses and living organisms". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 33 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:2010SyApM..33....1V. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2009.11.001. PMID 20005655.

- ^ van Nimwegen, Erik; Crutchfield, James P.; Huynen, Martijn (August 1999). "Neutral evolution of mutational robustness". PNAS. 96 (17): 9716–9720. arXiv:adap-org/9903006. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.9716V. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.17.9716. PMC 22276. PMID 10449760.

- ^ Wilke, Claus O.; Wang, Jia Lan; Ofria, Charles; Lenski, Richard E.; Adami, Christoph (2001). "Evolution of digital organisms at high mutation rates leads to survival of the flattest" (PDF). Nature. 412 (6844): 331–333. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..331W. doi:10.1038/35085569. PMID 11460163. S2CID 1482925.

- ^ Elena, S. F.; Agudelo-Romero, P.; Carrasco, P.; et al. (2008). "Experimental evolution of plant RNA viruses". Heredity. 100 (5): 478–483. Bibcode:2008Hered.100..478E. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6801088. PMC 7094686. PMID 18253158.

- ^ King, Andrew M.Q.; Lefkowitz, E.; Adams, M. J.; Carstens, E. B. (2012). Virus Taxonomy Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ Fauquet, C. M.; Fargette, D. (2005). "International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses and the 3,142 unassigned species". Virology Journal. 2: 64. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-2-64. PMC 1208960. PMID 16105179.

- ^ Gibbs, A. J. (2013). "Viral taxonomy needs a spring clean; its exploration era is over". Virology Journal. 10: 254. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-254. PMC 3751428. PMID 23938184.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1942). Systematics and the Origin of Species. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Wheeler, pp. 17–29

- ^ a b c d de Queiroz, K. (2005). "Ernst Mayr and the modern concept of species". PNAS. 102 (Supplement 1): 6600–6607. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6600D. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502030102. PMC 1131873. PMID 15851674.

- ^ Hopf, F. A.; Hopf, F. W. (1985). "The role of the Allee effect on species packing". Theoretical Population Biology. 27 (1): 27–50. Bibcode:1985TPBio..27...27H. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(85)90014-0.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Byerly, H. C.; Hopf, F. A.; Michod, R.E. (1985). "Sex and the emergence of species". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 117 (4): 665–690. Bibcode:1985JThBi.117..665B. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(85)80246-0. PMID 4094459.

- ^ Bernstein, Carol; Bernstein, Harris (1991). Aging, sex, and DNA repair. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-092860-6.

- ^ Michod, Richard E. (1995). Eros and Evolution: A Natural Philosophy of Sex. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-44232-8.

- ^ Hanage, William P. (2013), "Fuzzy species revisited", BMC Biology, 11 (41): 41, doi:10.1186/1741-7007-11-41, PMC 3626887, PMID 23587266

- ^ Koch, H. (2010). "Combining morphology and DNA barcoding resolves the taxonomy of Western Malagasy Liotrigona Moure, 1961" (PDF). African Invertebrates. 51 (2): 413–421. doi:10.5733/afin.051.0210. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2016.

- ^ De Queiroz, K. (2007). "Species concepts and species delimitation". Systematic Biology. 56 (6): 879–886. doi:10.1080/10635150701701083. PMID 18027281.

- ^ Fraser, C.; Alm, E. J.; Polz, M. F.; Spratt, B. G.; Hanage, W. P. (2009). "The bacterial species challenge: making sense of genetic and ecological diversity". Science. 323 (5915): 741–746. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..741F. doi:10.1126/science.1159388. PMID 19197054. S2CID 15763831.

- ^ . On the Origin of Species (1859) – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Darwin 1859 Chapter II, p. 59". Darwin-online.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Gevers, Dirk; Cohan, Frederick M.; Lawrence, Jeffrey G.; Spratt, Brian G.; Coenye, Tom; Feil, Edward J.; Stackebrandt, Erko; De Peer, Yves Van; Vandamme, Peter; Thompson, Fabiano L.; Swings, Jean (2005). "Opinion: Re-evaluating prokaryotic species". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (9): 733–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1236. PMID 16138101. S2CID 41706247.

- ^ Templeton, A. R. (1989). "The meaning of species and speciation: A genetic perspective". In Otte, D.; Endler, J. A. (eds.). Speciation and its Consequences. Sinauer Associates. pp. 3–27.

- ^ Edward G. Reekie; Fakhri A. Bazzaz (2005). Reproductive allocation in plants. Academic Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-12-088386-8. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ^ Rosselló-Mora, Ramon; Amann, Rudolf (January 2001). "The species concept for prokaryotes". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 25 (1): 39–67. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00571.x. PMID 11152940.

- ^ Andino, Raul; Domingo, Esteban (2015). "Viral quasispecies". Virology. 479–480: 46–51. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.022. PMC 4826558. PMID 25824477.

- ^ Biebricher, C. K.; Eigen, M. (2006). "What is a Quasispecies?". Quasispecies: Concept and Implications for Virology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 299. Springer. pp. 1–31. doi:10.1007/3-540-26397-7_1. ISBN 978-3-540-26397-5. PMID 16568894.

- ^ Teueman, A. E. (2009). "The Species-Concept in Palaeontology". Geological Magazine. 61 (8): 355–360. Bibcode:1924GeoM...61..355T. doi:10.1017/S001675680008660X. S2CID 84339122. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- ^ Zachos 2016, p. 101.

- ^ Zachos 2016, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Lahr, D. J.; Laughinghouse, H. D.; Oliverio, A. M.; Gao, F.; Katz, L. A. (2014). "How discordant morphological and molecular evolution among microorganisms can revise our notions of biodiversity on Earth". BioEssays. 36 (10): 950–959. doi:10.1002/bies.201400056. PMC 4288574. PMID 25156897.

- ^ a b c Melcher, Ulrich (2001). "Molecular genetics: Horizontal gene transfer". Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Bapteste, E.; et al. (May 2005). "Do orthologous gene phylogenies really support tree-thinking?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5 (33): 33. Bibcode:2005BMCEE...5...33B. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-33. PMC 1156881. PMID 15913459.

- ^ Williamson, David I. (2003). The Origins of Larvae. Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4020-1514-4.

- ^ Mishler, Brent D. (2022). "Ecology, evolution, and systematics in a post-species world". In Wilkins, John S.; Zachos, Frank E.; Pavlinov, Igor (eds.). Species problems and beyond: contemporary issues in philosophy and practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-367-85560-4. OCLC 1273727987.

- ^ a b Mishler, Brent D. (1999). "Getting Rid of Species?". In Wilson, R. (ed.). Species: New Interdisciplinary Essays (PDF). MIT Press. pp. 307–315. ISBN 978-0-262-73123-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2018.

- ^ Salzburger, Walter (November 2018). "Understanding explosive diversification through cichlid fish genomics". Nature Reviews Genetics. 19 (11): 705–717. doi:10.1038/s41576-018-0043-9. ISSN 1471-0064. PMID 30111830. S2CID 52008986.

- ^ a b c Wilkins, John S. (2022). "The Good Species". In Wilkins, John S.; Zachos, Frank E.; Pavlinov, Igor (eds.). Species problems and beyond: contemporary issues in philosophy and practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-367-85560-4. OCLC 1273727987.

- ^ Mishler, Brent D.; Wilkins, John S. (2018). "The Hunting of the SNaRC: A Snarky Solution to the Species Problem". Philosophy, Theory, and Practice in Biology. 10 (20220112). University of Michigan Library. doi:10.3998/ptpbio.16039257.0010.001. hdl:2027/spo.16039257.0010.001.

- ^ a b c d Laurin, Michel (3 August 2023). The Advent of PhyloCode: The Continuing Evolution of Biological Nomenclature. CRC Press. p. xv + 209. doi:10.1201/9781003092827. ISBN 978-1-003-09282-7.

- ^ Kitcher, Philip (June 1984). "Species". Philosophy of Science. 51 (2): 308–333. doi:10.1086/289182. S2CID 224836299.

I defend a view of the species category, pluralistic realism, which is designed to do justice to the insights of many different groups of systematists.

- ^ Pleijel, F.; Rouse, G. W. (22 March 2000). "Least-inclusive taxonomic unit: a new taxonomic concept for biology". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 267 (1443): 627–630. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1048. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690571. PMID 10787169.

- ^ Heywood, V. H. (1962). "The 'species aggregate' in theory and practice". In Heywood, V. H.; Löve, Á. (eds.). Symposium on Biosystematics, Montreal, October 1962. pp. 26–36.

- ^ Pimentel, David (2014). Biological Invasions: Economic and Environmental Costs of Alien Plant, Animal, and Microbe Species. CRC Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4200-4166-8. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018.

- ^ Jarvis, C. E. (1992). "Seventy-Two Proposals for the Conservation of Types of Selected Linnaean Generic Names, the Report of Subcommittee 3C on the Lectotypification of Linnaean Generic Names". Taxon. 41 (3): 552–583. Bibcode:1992Taxon..41..552J. doi:10.2307/1222833. JSTOR 1222833.

- ^ Wittzell, Hakan (1999). "Chloroplast DNA variation and reticulate evolution in sexual and apomictic sections of dandelions". Molecular Ecology. 8 (12): 2023–2035. Bibcode:1999MolEc...8.2023W. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00807.x. PMID 10632854. S2CID 25180463.

- ^ Dijk, Peter J. van (2003). "Ecological and evolutionary opportunities of apomixis: insights from Taraxacum and Chondrilla". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 358 (1434): 1113–1121. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1302. PMC 1693208. PMID 12831477.

- ^ Mallet, James; Beltrán, M.; Neukirchen, W.; Linares, M. (2007). "Natural hybridization in heliconiine butterflies: the species boundary as a continuum". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 28. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7...28M. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-28. PMC 1821009. PMID 17319954.

- ^ Ron, Santiago; Caminer, Marcel (2014). "Systematics of treefrogs of the Hypsiboas calcaratus and Hypsiboas fasciatus species complex (Anura, Hylidae) with the description of four new species". ZooKeys (370): 1–68. Bibcode:2014ZooK..370....1C. doi:10.3897/zookeys.370.6291. PMC 3904076. PMID 24478591.

- ^ Geml, J.; Tulloss, R. E.; Laursen, G. A.; Sasanova, N. A.; Taylor, D. L. (2008). "Evidence for strong inter- and intracontinental phylogeographic structure in Amanita muscaria, a wind-dispersed ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 48 (2): 694–701. Bibcode:2008MolPE..48..694G. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.04.029. PMID 18547823. S2CID 619242.

- ^ "Defining a species". University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Zachos 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Stamos, David N. (2003). The Species Problem: Biological Species, Ontology, and the Metaphysics of Biology. Lexington Books. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7391-6118-0. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ Moritz, C.; Schneider, C. J.; Wake, D. B. (1992). "Evolutionary Relationships Within the Ensatina eschscholtzii Complex Confirm the Ring Species Interpretation" (PDF). Systematic Biology. 41 (3): 273–291. doi:10.1093/sysbio/41.3.273. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2018.

- ^ Irwin, D. E.; Bensch, Staffan; Irwin, Jessica H.; Price, Trevor D. (2005). "Speciation by Distance in a Ring Species". Science. 307 (5708): 414–6. Bibcode:2005Sci...307..414I. doi:10.1126/science.1105201. PMID 15662011. S2CID 18347146.

- ^ Martens, Jochen; Päckert, Martin (2007). "Ring species – Do they exist in birds?". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 246 (4): 315–324. Bibcode:2007ZooAn.246..315M. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2007.07.004.

- ^ Alcaide, M.; Scordato, E. S. C.; Price, T. D.; Irwin, D. E. (2014). "Genomic divergence in a ring species complex". Nature. 511 (7507): 83–85. Bibcode:2014Natur.511...83A. doi:10.1038/nature13285. hdl:10261/101651. PMID 24870239. S2CID 4458956.

- ^ Liebers, Dorit; Knijff, Peter de; Helbig, Andreas J. (2004). "The herring gull complex is not a ring species". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1542): 893–901. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2679. PMC 1691675. PMID 15255043.

- ^ Highton, R. (1998). "Is Ensatina eschscholtzii a ring species?". Herpetologica. 54 (2): 254–278. JSTOR 3893431.

- ^ "A Word About Species Names ..." Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Hone, Dave (19 June 2013). "What's in a name? Why scientific names are important". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Lawley, Jonathan W.; Gamero-Mora, Edgar; Maronna, Maximiliano M.; Chiaverano, Luciano M.; Stampar, Sérgio N.; Hopcroft, Russell R.; Collins, Allen G.; Morandini, André C. (29 September 2022). "Morphology is not always useful for diagnosis, and that's ok: Species hypotheses should not be bound to a class of data. Reply to Brown and Gibbons (S Afr J Sci. 2022;118(9/10), Art. #12590)". South African Journal of Science. 118 (9/10). doi:10.17159/sajs.2022/14495. S2CID 252562185.

- ^ One example of an abstract of an article naming a new species can be found at Wellner, S.; Lodders, N.; Kämpfer, P. (2012). "Methylobacterium cerastii sp. nov., a novel species isolated from the leaf surface of Cerastium holosteoides". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 62 (Pt 4): 917–924. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.030767-0. PMID 21669927.

- ^ Hitchcock, A. S. (1921), "The Type Concept in Systematic Botany", American Journal of Botany, 8 (5): 251–255, doi:10.2307/2434993, JSTOR 2434993

- ^ Nicholson, Dan H. "Botanical nomenclature, types, & standard reference works". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ "International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, Recommendation 25C". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Winston, Judith E. (1999). Describing species. Practical taxonomic procedure for biologists. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 141–144.

- ^ "Home – Taxonomy – NCBI". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 19 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "KEGG Organisms: Complete Genomes". Genome.jp. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Taxonomy". Uniprot.org. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "ITIS: Homo sapiens". Catalogue of Life. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Simpson, George Gaylord (1945). "The Principles of Classification and a Classification of Mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 85: 23.

- ^ Chase, Bob (2005). "Upstart Antichrist". History Workshop Journal. 60 (1): 202–206. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbi042. S2CID 201790420.

- ^ Laurin, Michel (23 July 2023). "The PhyloCode: The logical outcome of millennia of evolution of biological nomenclature?" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 52 (6): 543–555. doi:10.1111/zsc.12625. ISSN 0300-3256. S2CID 260224728.

- ^ Wilson, Philip (2016). "sensu stricto, sensu lato". AZ of tree terms. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Glossary: sensu". International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b Barton, N. H. (June 2010). "What role does natural selection play in speciation?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 365 (1547): 1825–1840. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0001. PMC 2871892. PMID 20439284.

- ^ a b Vaux, Felix; Trewick, Steven A.; Morgan-Richards, Mary (2017). "Speciation through the looking-glass". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 120 (2): 480–488. doi:10.1111/bij.12872.

- ^ Zachos 2016, pp. 77–96.

- ^ Cook, Orator F. (30 March 1906). "Factors of species-formation". Science. 23 (587): 506–507. Bibcode:1906Sci....23..506C. doi:10.1126/science.23.587.506. PMID 17789700.

- ^ Cook, Orator F. (November 1908). "Evolution Without Isolation". The American Naturalist. 42 (503): 727–731. Bibcode:1908ANat...42..727C. doi:10.1086/279001. S2CID 84565616.

- ^ Via, Sara (16 June 2009). "Natural selection in action during speciation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (Suppl 1): 9939–9946. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9939V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901397106. PMC 2702801. PMID 19528641.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst (1982). "Speciation and Macroevolution". Evolution. 36 (6): 1119–1132. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1982.tb05483.x. PMID 28563569. S2CID 27401899.

- ^ Pennisi, Elizabeth (2004). "Researchers Trade Insights about Gene Swapping" (PDF). Science. 334–335: 335. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2006.

- ^ Zhaxybayeva, Olga; Peter Gogarten, J. (2004). "Cladogenesis, coalescence and the evolution of the three domains of life" (PDF). Trends in Genetics. 20 (4): 182–187. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2004.02.004. PMID 15041172. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2009.

- ^ Venton, Danielle (2017). "Highlight: Applying the Biological Species Concept across All of Life". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (3): 502–503. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx045. PMC 5381533. PMID 28391326.

- ^ Bobay, Louis-Marie; Ochman, Howard (2017). "Biological Species Are Universal across Life's Domains". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (3): 491–501. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx026. PMC 5381558. PMID 28186559.

- ^ Kunin, W. E.; Gaston, Kevin, eds. (1996). The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare–common differences. Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-63380-5. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015.

- ^ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, Stephen C. (2000). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. p. preface x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6.

- ^ Zachos 2016, p. 82.

- ^ Zachos, Frank E. (2015). "Taxonomic inflation, the Phylogenetic Species Concept and lineages in the Tree of Life – a cautionary comment on species splitting". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 53 (2): 180–184. doi:10.1111/jzs.12088.

- ^ Agapow, Paul-Michael; Bininda-Emonds, Olaf R. P.; Crandall, Keith A.; Gittleman, John L.; Mace, Georgina M.; Marshall, Jonathon C.; Purvis, Andy (2004). "The Impact of Species Concept on Biodiversity Studies" (PDF). The Quarterly Review of Biology. 79 (2): 161–179. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.2974. doi:10.1086/383542. JSTOR 10.1086/383542. PMID 15232950. S2CID 2698838. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b Hey, Jody (July 2001). "The mind of the species problem". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 16 (7): 326–329. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02145-0. PMID 11403864.

- ^ Haig, Susan M.; Allendorf, F.W. (2006). "Hybrids and Policy". In Scott, J. Michael; Goble, D. D.; Davis, Frank W. (eds.). The Endangered Species Act at Thirty, Volume 2: Conserving Biodiversity in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Washington: Island Press. pp. 150–163. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018.

- ^ Faith, Daniel P. (1 January 1992). "Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity". Biological Conservation. 61 (1): 1–10. Bibcode:1992BCons..61....1F. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Vane-Wright, R. I.; Humphries, C. J.; Williams, P. H. (1991). "What to protect? – systematics and the agony of choice". Biological Conservation. 55 (3): 235–254. Bibcode:1991BCons..55..235V. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90030-D.

- ^ Pellegrin, Pierre (1986). Aristotle's classification of animals: biology and the conceptual unity of the Aristotelian corpus. Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Pr. p. xiv + 235. ISBN 0-520-05502-0.

- ^ Laurin, Michel; Humar, Marcel (10 January 2022). "Phylogenetic signal in characters from Aristotle's History of Animals". Comptes Rendus Palevol (in French) (1). doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2022v21a1. S2CID 245863171.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie (2014). The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Rigato, Emanuele; Minelli, Alessandro (28 June 2013). "The great chain of being is still here". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 6 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1936-6434-6-18. ISSN 1936-6434.

- ^ Ray, John (1686). Historia plantarum generalis, Tome I, Libr. I. p. Chap. XX, page 40., quoted in Mayr, Ernst (1982). The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance. Belknap Press. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-674-36445-5.

- ^ Davis, P. H.; Heywood, V. H. (1973). Principles of Angiosperm Taxonomy. Huntington, NY: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. p. 17.

- ^ Magnol, Petrus (1689). Prodromus historiae generalis plantarum in quo familiae plantarum per tabulas disponuntur (in Latin). Pech. p. 79.

- ^ Tournefort, Joseph Pitton de (1694). Elemens de botanique, ou Methode pour connoître les plantes. I. [Texte.] / . Par Mr Pitton Tournefort... [T. I-III]. Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale. p. 562.

- ^ Jussieu, Antoine-Laurent de (1789). Antonii Laurentii de Jussieu ... Genera plantarum secundum ordines naturales disposita: juxta methodum in horto regio Parisiensi exaratam, anno M.DCC.LXXIV. (in Latin). Apud viduam Herissant, typographum, viâ novâ B.M. sub signo Crucis Aureæ. Et Theophilum Barrois, ad ripam Augustinianorum. p. 498.

- ^ Reveal, James L.; Pringle, James S. (1993). "7. Taxonomic Botany and Floristics". Flora of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-19-505713-3.

- ^ Simpson, George Gaylord (1961). Principles of Animal Taxonomy. Columbia University Press. pp. 56–57.

- ^ Mahoney, Edward P. (1987). "Lovejoy and the Hierarchy of Being". Journal of the History of Ideas. 48 (2): 211–230. doi:10.2307/2709555. JSTOR 2709555.

- ^ "Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778)". UCMP Berkeley. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard: Belknap Harvard. pp. 170–197. ISBN 978-0-674-00613-3.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 177–223 and passim. ISBN 978-0-520-23693-6.

- ^ Menand, Louis (2001). The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-374-70638-8.

Sources

[edit]- Claridge, M. F.; Dawah, H. A.; Wilson, M. R., eds. (1997). Species: The Units of Biodiversity. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-63120-7.

- Wheeler, Quentin; Meier, Rudolf, eds. (2000). Species Concepts and Phylogenetic Theory: A Debate. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10143-1.

- Zachos, Frank E. (2016). Species Concepts in Biology: Historical Development, Theoretical Foundations and Practical Relevance. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-44964-7.

External links

[edit]- Wikispecies – The free species directory that anyone can edit from the Wikimedia Foundation

- Barcoding of species

- Catalogue of Life

- European Species Names in Linnaean, Czech, English, German and French

- "Species" entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- VisualTaxa

KSF

KSF