Spherical trigonometry

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 27 min

Spherical trigonometry is the branch of spherical geometry that deals with the metrical relationships between the sides and angles of spherical triangles, traditionally expressed using trigonometric functions. On the sphere, geodesics are great circles. Spherical trigonometry is of great importance for calculations in astronomy, geodesy, and navigation.

The origins of spherical trigonometry in Greek mathematics and the major developments in Islamic mathematics are discussed fully in History of trigonometry and Mathematics in medieval Islam. The subject came to fruition in Early Modern times with important developments by John Napier, Delambre and others, and attained an essentially complete form by the end of the nineteenth century with the publication of Isaac Todhunter's textbook Spherical trigonometry for the use of colleges and Schools.[1] Since then, significant developments have been the application of vector methods, quaternion methods, and the use of numerical methods.

Preliminaries

[edit]

Spherical polygons

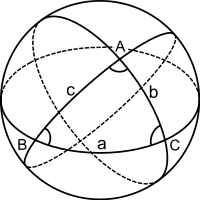

[edit]A spherical polygon is a polygon on the surface of the sphere. Its sides are arcs of great circles—the spherical geometry equivalent of line segments in plane geometry.

Such polygons may have any number of sides greater than 1. Two-sided spherical polygons—lunes, also called digons or bi-angles—are bounded by two great-circle arcs: a familiar example is the curved outward-facing surface of a segment of an orange. Three arcs serve to define a spherical triangle, the principal subject of this article. Polygons with higher numbers of sides (4-sided spherical quadrilaterals, 5-sided spherical pentagons, etc.) are defined in similar manner. Analogously to their plane counterparts, spherical polygons with more than 3 sides can always be treated as the composition of spherical triangles.

One spherical polygon with interesting properties is the pentagramma mirificum, a 5-sided spherical star polygon with a right angle at every vertex.

From this point in the article, discussion will be restricted to spherical triangles, referred to simply as triangles.

Notation

[edit]

- Both vertices and angles at the vertices of a triangle are denoted by the same upper case letters A, B, and C.

- Sides are denoted by lower-case letters: a, b, and c. The sphere has a radius of 1, and so the side lengths and lower case angles are equivalent (see arc length).

- The angle A (respectively, B and C) may be regarded either as the dihedral angle between the two planes that intersect the sphere at the vertex A, or, equivalently, as the angle between the tangents of the great circle arcs where they meet at the vertex.

- Angles are expressed in radians. The angles of proper spherical triangles are (by convention) less than π, so that (Todhunter,[1] Art.22,32).

In particular, the sum of the angles of a spherical triangle is strictly greater than the sum of the angles of a triangle defined on the Euclidean plane, which is always exactly π radians.

- Sides are also expressed in radians. A side (regarded as a great circle arc) is measured by the angle that it subtends at the centre. On the unit sphere, this radian measure is numerically equal to the arc length. By convention, the sides of proper spherical triangles are less than π, so that (Todhunter,[1] Art.22,32).

- The sphere's radius is taken as unity. For specific practical problems on a sphere of radius R the measured lengths of the sides must be divided by R before using the identities given below. Likewise, after a calculation on the unit sphere the sides a, b, and c must be multiplied by R.

Polar triangles

[edit]

The polar triangle associated with a triangle △ABC is defined as follows. Consider the great circle that contains the side BC. This great circle is defined by the intersection of a diametral plane with the surface. Draw the normal to that plane at the centre: it intersects the surface at two points and the point that is on the same side of the plane as A is (conventionally) termed the pole of A and it is denoted by A'. The points B' and C' are defined similarly.

The triangle △A'B'C' is the polar triangle corresponding to triangle △ABC. The angles and sides of the polar triangle are given by (Todhunter,[1] Art.27) Therefore, if any identity is proved for △ABC then we can immediately derive a second identity by applying the first identity to the polar triangle by making the above substitutions. This is how the supplemental cosine equations are derived from the cosine equations. Similarly, the identities for a quadrantal triangle can be derived from those for a right-angled triangle. The polar triangle of a polar triangle is the original triangle.

If the 3 × 3 matrix M has the positions A, B, and C as its columns then the rows of the matrix inverse M−1, if normalized to unit length, are the positions A′, B′, and C′. In particular, when △A′B′C′ is the polar triangle of △ABC then △ABC is the polar triangle of △A′B′C′.

Cosine rules and sine rules

[edit]Cosine rules

[edit]The cosine rule is the fundamental identity of spherical trigonometry: all other identities, including the sine rule, may be derived from the cosine rule:

These identities generalize the cosine rule of plane trigonometry, to which they are asymptotically equivalent in the limit of small interior angles. (On the unit sphere, if set and etc.; see Spherical law of cosines.)

Sine rules

[edit]The spherical law of sines is given by the formula These identities approximate the sine rule of plane trigonometry when the sides are much smaller than the radius of the sphere.

Derivation of the cosine rule

[edit]

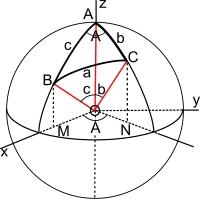

The spherical cosine formulae were originally proved by elementary geometry and the planar cosine rule (Todhunter,[1] Art.37). He also gives a derivation using simple coordinate geometry and the planar cosine rule (Art.60). The approach outlined here uses simpler vector methods. (These methods are also discussed at Spherical law of cosines.)

Consider three unit vectors OA→, OB→, OC→ drawn from the origin to the vertices of the triangle (on the unit sphere). The arc BC subtends an angle of magnitude a at the centre and therefore OB→ · OC→ = cos a. Introduce a Cartesian basis with OA→ along the z-axis and OB→ in the xz-plane making an angle c with the z-axis. The vector OC→ projects to ON in the xy-plane and the angle between ON and the x-axis is A. Therefore, the three vectors have components:

The scalar product OB→ · OC→ in terms of the components is Equating the two expressions for the scalar product gives This equation can be re-arranged to give explicit expressions for the angle in terms of the sides:

The other cosine rules are obtained by cyclic permutations.

Derivation of the sine rule

[edit]This derivation is given in Todhunter,[1] (Art.40). From the identity and the explicit expression for cos A given immediately above Since the right hand side is invariant under a cyclic permutation of a, b, and c the spherical sine rule follows immediately.

Alternative derivations

[edit]There are many ways of deriving the fundamental cosine and sine rules and the other rules developed in the following sections. For example, Todhunter[1] gives two proofs of the cosine rule (Articles 37 and 60) and two proofs of the sine rule (Articles 40 and 42). The page on Spherical law of cosines gives four different proofs of the cosine rule. Text books on geodesy[2] and spherical astronomy[3] give different proofs and the online resources of MathWorld provide yet more.[4] There are even more exotic derivations, such as that of Banerjee[5] who derives the formulae using the linear algebra of projection matrices and also quotes methods in differential geometry and the group theory of rotations.

The derivation of the cosine rule presented above has the merits of simplicity and directness and the derivation of the sine rule emphasises the fact that no separate proof is required other than the cosine rule. However, the above geometry may be used to give an independent proof of the sine rule. The scalar triple product, OA→ · (OB→ × OC→) evaluates to sin b sin c sin A in the basis shown. Similarly, in a basis oriented with the z-axis along OB→, the triple product OB→ · (OC→ × OA→), evaluates to sin c sin a sin B. Therefore, the invariance of the triple product under cyclic permutations gives sin b sin A = sin a sin B which is the first of the sine rules. See curved variations of the law of sines to see details of this derivation.

Differential variations

[edit]When any three of the differentials da, db, dc, dA, dB, dC are known, the following equations, which are found by differentiating the cosine rule and using the sine rule, can be used to calculate the other three by elimination:[6]

Identities

[edit]Supplemental cosine rules

[edit]Applying the cosine rules to the polar triangle gives (Todhunter,[1] Art.47), i.e. replacing A by π − a, a by π − A etc.,

Cotangent four-part formulae

[edit]The six parts of a triangle may be written in cyclic order as (aCbAcB). The cotangent, or four-part, formulae relate two sides and two angles forming four consecutive parts around the triangle, for example (aCbA) or BaCb). In such a set there are inner and outer parts: for example in the set (BaCb) the inner angle is C, the inner side is a, the outer angle is B, the outer side is b. The cotangent rule may be written as (Todhunter,[1] Art.44) and the six possible equations are (with the relevant set shown at right): To prove the first formula start from the first cosine rule and on the right-hand side substitute for cos c from the third cosine rule: The result follows on dividing by sin a sin b. Similar techniques with the other two cosine rules give CT3 and CT5. The other three equations follow by applying rules 1, 3 and 5 to the polar triangle.

Half-angle and half-side formulae

[edit]With and

Another twelve identities follow by cyclic permutation.

The proof (Todhunter,[1] Art.49) of the first formula starts from the identity using the cosine rule to express A in terms of the sides and replacing the sum of two cosines by a product. (See sum-to-product identities.) The second formula starts from the identity the third is a quotient and the remainder follow by applying the results to the polar triangle.

Delambre analogies

[edit]The Delambre analogies (also called Gauss analogies) were published independently by Delambre, Gauss, and Mollweide in 1807–1809.[7]

Another eight identities follow by cyclic permutation.

Proved by expanding the numerators and using the half angle formulae. (Todhunter,[1] Art.54 and Delambre[8])

Napier's analogies

[edit]

Another eight identities follow by cyclic permutation.

These identities follow by division of the Delambre formulae. (Todhunter,[1] Art.52)

Taking quotients of these yields the law of tangents, first stated by Persian mathematician Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274),

Napier's rules for right spherical triangles

[edit]

When one of the angles, say C, of a spherical triangle is equal to π/2 the various identities given above are considerably simplified. There are ten identities relating three elements chosen from the set a, b, c, A, and B.

Napier[9] provided an elegant mnemonic aid for the ten independent equations: the mnemonic is called Napier's circle or Napier's pentagon (when the circle in the above figure, right, is replaced by a pentagon).

First, write the six parts of the triangle (three vertex angles, three arc angles for the sides) in the order they occur around any circuit of the triangle: for the triangle shown above left, going clockwise starting with a gives aCbAcB. Next replace the parts that are not adjacent to C (that is A, c, and B) by their complements and then delete the angle C from the list. The remaining parts can then be drawn as five ordered, equal slices of a pentagram, or circle, as shown in the above figure (right). For any choice of three contiguous parts, one (the middle part) will be adjacent to two parts and opposite the other two parts. The ten Napier's Rules are given by

- sine of the middle part = the product of the tangents of the adjacent parts

- sine of the middle part = the product of the cosines of the opposite parts

The key for remembering which trigonometric function goes with which part is to look at the first vowel of the kind of part: middle parts take the sine, adjacent parts take the tangent, and opposite parts take the cosine. For an example, starting with the sector containing a we have: The full set of rules for the right spherical triangle is (Todhunter,[1] Art.62)

Napier's rules for quadrantal triangles

[edit]

A quadrantal spherical triangle is defined to be a spherical triangle in which one of the sides subtends an angle of π/2 radians at the centre of the sphere: on the unit sphere the side has length π/2. In the case that the side c has length π/2 on the unit sphere the equations governing the remaining sides and angles may be obtained by applying the rules for the right spherical triangle of the previous section to the polar triangle △A'B'C' with sides a', b', c' such that A' = π − a, a' = π − A etc. The results are:

Five-part rules

[edit]Substituting the second cosine rule into the first and simplifying gives: Cancelling the factor of sin c gives

Similar substitutions in the other cosine and supplementary cosine formulae give a large variety of 5-part rules. They are rarely used.

Cagnoli's Equation

[edit]Multiplying the first cosine rule by cos A gives Similarly multiplying the first supplementary cosine rule by cos a yields Subtracting the two and noting that it follows from the sine rules that produces Cagnoli's equation which is a relation between the six parts of the spherical triangle.[10]

Solution of triangles

[edit]Oblique triangles

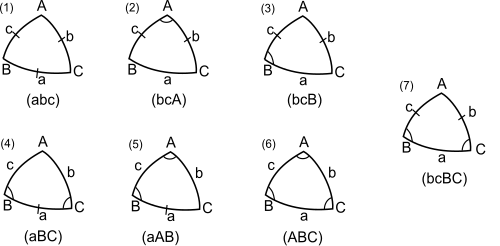

[edit]The solution of triangles is the principal purpose of spherical trigonometry: given three, four or five elements of the triangle, determine the others. The case of five given elements is trivial, requiring only a single application of the sine rule. For four given elements there is one non-trivial case, which is discussed below. For three given elements there are six cases: three sides, two sides and an included or opposite angle, two angles and an included or opposite side, or three angles. (The last case has no analogue in planar trigonometry.) No single method solves all cases. The figure below shows the seven non-trivial cases: in each case the given sides are marked with a cross-bar and the given angles with an arc. (The given elements are also listed below the triangle). In the summary notation here such as ASA, A refers to a given angle and S refers to a given side, and the sequence of A's and S's in the notation refers to the corresponding sequence in the triangle.

- Case 1: three sides given (SSS). The cosine rule may be used to give the angles A, B, and C but, to avoid ambiguities, the half angle formulae are preferred.

- Case 2: two sides and an included angle given (SAS). The cosine rule gives a and then we are back to Case 1.

- Case 3: two sides and an opposite angle given (SSA). The sine rule gives C and then we have Case 7. There are either one or two solutions.

- Case 4: two angles and an included side given (ASA). The four-part cotangent formulae for sets (cBaC) and (BaCb) give c and b, then A follows from the sine rule.

- Case 5: two angles and an opposite side given (AAS). The sine rule gives b and then we have Case 7 (rotated). There are either one or two solutions.

- Case 6: three angles given (AAA). The supplemental cosine rule may be used to give the sides a, b, and c but, to avoid ambiguities, the half-side formulae are preferred.

- Case 7: two angles and two opposite sides given (SSAA). Use Napier's analogies for a and A; or, use Case 3 (SSA) or case 5 (AAS).

The solution methods listed here are not the only possible choices: many others are possible. In general it is better to choose methods that avoid taking an inverse sine because of the possible ambiguity between an angle and its supplement. The use of half-angle formulae is often advisable because half-angles will be less than π/2 and therefore free from ambiguity. There is a full discussion in Todhunter. The article Solution of triangles#Solving spherical triangles presents variants on these methods with a slightly different notation.

There is a full discussion of the solution of oblique triangles in Todhunter.[1]: Chap. VI See also the discussion in Ross.[11] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was the first to list the six distinct cases (2–7 in the diagram) of a right triangle in spherical trigonometry.[12]

Solution by right-angled triangles

[edit]Another approach is to split the triangle into two right-angled triangles. For example, take the Case 3 example where b, c, and B are given. Construct the great circle from A that is normal to the side BC at the point D. Use Napier's rules to solve the triangle △ABD: use c and B to find the sides AD and BD and the angle ∠BAD. Then use Napier's rules to solve the triangle △ACD: that is use AD and b to find the side DC and the angles C and ∠DAC. The angle A and side a follow by addition.

Numerical considerations

[edit]Not all of the rules obtained are numerically robust in extreme examples, for example when an angle approaches zero or π. Problems and solutions may have to be examined carefully, particularly when writing code to solve an arbitrary triangle.

Area and spherical excess

[edit]

Consider an N-sided spherical polygon and let An denote the n-th interior angle. The area of such a polygon is given by (Todhunter,[1] Art.99)

Via triangulation of the spherical polygon, the proof of this theorem can be reduced to a proof for a spherical triangle. For the case of a spherical triangle with angles A, B, and C this is Girard's theorem where E is the amount by which the sum of the angles exceeds π radians, called the spherical excess of the triangle. This theorem is named after its author, Albert Girard.[13] An earlier proof was derived, but not published, by the English mathematician Thomas Harriot in 1603.[14] On a sphere of radius R both of the above area expressions are multiplied by R2. The definition of the excess is independent of the radius of the sphere.

The converse result may be written as

Since the area of a triangle cannot be negative the spherical excess is always positive. It is not necessarily small, because the sum of the angles may attain 5π (3π for proper angles). For example, an octant of a sphere is a spherical triangle with three right angles, so that the excess is π/2. In practical applications it is often small: for example the triangles of geodetic survey typically have a spherical excess much less than 1' of arc.[15] On the Earth the excess of an equilateral triangle with sides 21.3 km (and area 393 km2) is approximately 1 arc second.

There are many formulae for the excess. For example, Todhunter,[1] (Art.101—103) gives ten examples including that of L'Huilier: where . This formula is reminiscent of Heron's formula for planar triangles.

Because some triangles are badly characterized by their edges (e.g., if ), it is often better to use the formula for the excess in terms of two edges and their included angle

When triangle △ABC is a right triangle with right angle at C, then cos C = 0 and sin C = 1, so this reduces to

Angle deficit is defined similarly for hyperbolic geometry.

From latitude and longitude

[edit]The spherical excess of a spherical quadrangle bounded by the equator, the two meridians of longitudes and and the great-circle arc between two points with longitude and latitude and is

This result is obtained from one of Napier's analogies. In the limit where are all small, this reduces to the familiar trapezoidal area, .

The area of a polygon can be calculated from individual quadrangles of the above type, from (analogously) individual triangle bounded by a segment of the polygon and two meridians,[16] by a line integral with Green's theorem,[17] or via an equal-area projection as commonly done in GIS. The other algorithms can still be used with the side lengths calculated using a great-circle distance formula.

See also

[edit]- Air navigation

- Celestial navigation

- Ellipsoidal trigonometry

- Great-circle distance or spherical distance

- Lenart sphere

- Schwarz triangle

- Spherical geometry

- Spherical polyhedron

- Triangulation (surveying)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Todhunter, Isaac (1886). Spherical Trigonometry (5th ed.). MacMillan. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- ^ Clarke, Alexander Ross (1880). Geodesy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 2484948 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Smart, W.M. (1977). Text-Book on Spherical Astronomy (6th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Chapter 1 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Spherical Trigonometry". MathWorld. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Banerjee, Sudipto (2004), "Revisiting Spherical Trigonometry with Orthogonal Projectors", The College Mathematics Journal, 35 (5), Mathematical Association of America: 375–381, doi:10.1080/07468342.2004.11922099, JSTOR 4146847, retrieved 2016-01-10

- ^ William Chauvenet (1887). A Treatise on Plane and Spherical Trigonometry (9th ed.). J.B. Lippincott Company. p. 240. ISBN 978-3-382-17783-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Todhunter, Isaac (1873). "Note on the history of certain formulæ in spherical trigonometry". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 45 (298): 98–100. doi:10.1080/14786447308640820.

- ^ Delambre, J. B. J. (1807). Connaissance des Tems 1809. p. 445. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ^ Napier, J (1614). Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Constructio. p. 50. Retrieved 2016-05-14. Translated by William Rae Macdonald (1889) The Construction of the Wonderful Canon of Logarithms. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons.

- ^ Chauvenet, William (1867). A Treatise on Plane and Spherical Trigonometry. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 165. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ Ross, Debra Anne. Master Math: Trigonometry, Career Press, 2002.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Nasir al-Din al-Tusi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews "One of al-Tusi's most important mathematical contributions was the creation of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right rather than as just a tool for astronomical applications. In Treatise on the quadrilateral al-Tusi gave the first extant exposition of the whole system of plane and spherical trigonometry. This work is really the first in history on trigonometry as an independent branch of pure mathematics and the first in which all six cases for a right-angled spherical triangle are set forth"

- ^ Another proof of Girard's theorem: Polking (1999) "The area of a spherical triangle. Girard's Theorem." (Mirror of a personal website).

- ^ Arianrhod, Robyn (2019). Thomas Harriot: a life in science. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-027185-5.

- ^ This follows from Legendre's theorem on spherical triangles whenever the area of the triangle is small relative to the surface area of the entire Earth; see Clarke, Alexander Ross (1880). Geodesy. Clarendon Press. (Chapters 2 and 9).

- ^ Chamberlain, Robert G.; Duquette, William H. (17 April 2007). Some algorithms for polygons on a sphere. Association of American Geographers Annual Meeting. NASA JPL. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Surface area of polygon on sphere or ellipsoid – MATLAB areaint". www.mathworks.com. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Spherical Trigonometry". MathWorld. a more thorough list of identities, with some derivation

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Spherical Triangle". MathWorld. a more thorough list of identities, with some derivation

- TriSph A free software to solve the spherical triangles, configurable to different practical applications and configured for gnomonic

- "Revisiting Spherical Trigonometry with Orthogonal Projectors" by Sudipto Banerjee. The paper derives the spherical law of cosines and law of sines using elementary linear algebra and projection matrices.

- "A Visual Proof of Girard's Theorem". Wolfram Demonstrations Project. by Okay Arik

- "The Book of Instruction on Deviant Planes and Simple Planes", a manuscript in Arabic that dates back to 1740 and talks about spherical trigonometry, with diagrams

- Some Algorithms for Polygons on a Sphere Robert G. Chamberlain, William H. Duquette, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The paper develops and explains many useful formulae, perhaps with a focus on navigation and cartography.

- Online computation of spherical triangles

KSF

KSF

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cos a&=\cos b\cos c+\sin b\sin c\cos A,\\[2pt]\cos b&=\cos c\cos a+\sin c\sin a\cos B,\\[2pt]\cos c&=\cos a\cos b+\sin a\sin b\cos C.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9577fb285783273a9f934fa5aa9244afc51b67a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin ^{2}A&=1-\left({\frac {\cos a-\cos b\cos c}{\sin b\sin c}}\right)^{2}\\[5pt]&={\frac {(1-\cos ^{2}b)(1-\cos ^{2}c)-(\cos a-\cos b\cos c)^{2}}{\sin ^{2}\!b\,\sin ^{2}\!c}}\\[5pt]{\frac {\sin A}{\sin a}}&={\frac {\sqrt {1-\cos ^{2}\!a-\cos ^{2}\!b-\cos ^{2}\!c+2\cos a\cos b\cos c}}{\sin a\sin b\sin c}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32a58ccdc18cbb4901cf8290690f7ea26795da0f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{alignedat}{5}{\text{(CT1)}}&&\qquad \cos b\,\cos C&=\cot a\,\sin b-\cot A\,\sin C\qquad &&(aCbA)\\[0ex]{\text{(CT2)}}&&\cos b\,\cos A&=\cot c\,\sin b-\cot C\,\sin A&&(CbAc)\\[0ex]{\text{(CT3)}}&&\cos c\,\cos A&=\cot b\,\sin c-\cot B\,\sin A&&(bAcB)\\[0ex]{\text{(CT4)}}&&\cos c\,\cos B&=\cot a\,\sin c-\cot A\,\sin B&&(AcBa)\\[0ex]{\text{(CT5)}}&&\cos a\,\cos B&=\cot c\,\sin a-\cot C\,\sin B&&(cBaC)\\[0ex]{\text{(CT6)}}&&\cos a\,\cos C&=\cot b\,\sin a-\cot B\,\sin C&&(BaCb)\end{alignedat}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90d13969a2c9bbfa8f85f314d58b3919ec6e5f75)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{alignedat}{5}\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}A&={\sqrt {\frac {\sin(s-b)\sin(s-c)}{\sin b\sin c}}}&\qquad \qquad \sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}a&={\sqrt {\frac {-\cos S\cos(S-A)}{\sin B\sin C}}}\\[2ex]\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}A&={\sqrt {\frac {\sin s\sin(s-a)}{\sin b\sin c}}}&\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}a&={\sqrt {\frac {\cos(S-B)\cos(S-C)}{\sin B\sin C}}}\\[2ex]\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}A&={\sqrt {\frac {\sin(s-b)\sin(s-c)}{\sin s\sin(s-a)}}}&\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}a&={\sqrt {\frac {-\cos S\cos(S-A)}{\cos(S-B)\cos(S-C)}}}\end{alignedat}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/df42fe32e35222a02674b0673823555f736001d4)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}C}}={\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}c}}&\qquad \qquad &{\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}C}}={\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}c}}\\[2ex]{\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}C}}={\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}c}}&\qquad &{\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}C}}={\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}c}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7173d7a1760fde7fae2dbe91bb9835d291a625ae)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)={\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)}}\cot {\tfrac {1}{2}}C&\qquad &\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)={\frac {\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)}{\cos {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)}}\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}c\\[2ex]\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)={\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a+b)}}\cot {\tfrac {1}{2}}C&\qquad &\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}(a-b)={\frac {\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A-B)}{\sin {\tfrac {1}{2}}(A+B)}}\tan {\tfrac {1}{2}}c\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/596487869380112ba5168fe57b6589617320d21f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sin a&=\tan({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-B)\,\tan b\\[2pt]&=\cos({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-c)\,\cos({\tfrac {\pi }{2}}-A)\\[2pt]&=\cot B\,\tan b\\[4pt]&=\sin c\,\sin A.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3b83237799af2d4a6cc604b645f77c1faefd6a06)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cos a&=(\cos a\,\cos c+\sin a\,\sin c\,\cos B)\cos c+\sin b\,\sin c\,\cos A\\[4pt]\cos a\,\sin ^{2}c&=\sin a\,\cos c\,\sin c\,\cos B+\sin b\,\sin c\,\cos A\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd9fda3ed16f39eb41d0b094803de2b99b16b85d)