Standing on the shoulders of giants

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 13 min

The phrase "standing on the shoulders of giants" is a metaphor which means "using the understanding gained by major thinkers who have gone before in order to make intellectual progress".[1]

It is a metaphor of dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants (Latin: nani gigantum humeris insidentes) and expresses the meaning of "discovering truth by building on previous discoveries".[2] This concept has been dated to the 12th century and, according to John of Salisbury, is attributed to Bernard of Chartres. But its most familiar and popular expression occurs in a 1675 letter by Isaac Newton: "if I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."[3]

Early references

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]The earliest documented attestation of this aphorism appears in 1123 in William of Conches's Glosses on Priscian's Institutiones grammaticae.[4] Where Priscian says quanto juniores, tanto perspicaciores (young men simply can see more sharply), William writes:

The ancients had only the books which they themselves wrote, but we have all their books and moreover all those which have been written from the beginning until our time.… Hence we are like a dwarf perched on the shoulders of a giant. The former sees further than the giant, not because of his own stature, but because of the stature of his bearer. Similarly, we [moderns] see more than the ancients, because our writings, modest as they are, are added to their great works.[5]

The same aphorism was attributed to Bernard of Chartres by John of Salisbury, who in 1159 wrote:

Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature.[9][10]

According to medieval historian Richard William Southern, Bernard was comparing contemporary 12th century scholars to the ancient scholars of Greece and Rome.[11] A similar conceit also appears in a contemporary work on church history by Ordericus Vitalis.[12]

[The phrase] sums up the quality of the cathedral schools in the history of learning, and indeed characterizes the age which opened with Gerbert (950–1003) and Fulbert (960–1028) and closed in the first quarter of the 12th century with Peter Abelard. [The phrase] is not a great claim; neither, however, is it an example of abasement before the shrine of antiquity. It is a very shrewd and just remark, and the important and original point was the dwarf could see a little further than the giant. That this was possible was above all due to the cathedral schools with their lack of a well-rooted tradition and their freedom from a clearly defined routine of study.

Religious texts

[edit]

The visual image (from Bernard of Chartres) appears in the stained glass of the south transept of Chartres Cathedral. The tall windows under the rose window show the four major prophets of the Hebrew Bible (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel) as gigantic figures, and the four New Testament evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) as ordinary-size people sitting on their shoulders. The evangelists, though smaller, "see more" than the huge prophets (since they saw the Messiah about whom the prophets spoke).

The phrase also appears in the works of the Jewish tosaphist Isaiah di Trani (c. 1180 – c. 1250):[13]

Should Joshua the son of Nun endorse a mistaken position, I would reject it out of hand, I do not hesitate to express my opinion, regarding such matters in accordance with the modicum of intelligence allotted to me. I was never arrogant claiming "My Wisdom served me well". Instead I applied to myself the parable of the philosophers. For I heard the following from the philosophers, The wisest of the philosophers was asked: "We admit that our predecessors were wiser than we. At the same time we criticize their comments, often rejecting them and claiming that the truth rests with us. How is this possible?" The wise philosopher responded: "Who sees further a dwarf or a giant? Surely a giant for his eyes are situated at a higher level than those of the dwarf. But if the dwarf is placed on the shoulders of the giant who sees further? ... So too we are dwarfs astride the shoulders of giants. We master their wisdom and move beyond it. Due to their wisdom we grow wise and are able to say all that we say, but not because we are greater than they.

Early modern and modern references

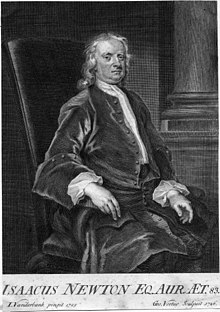

[edit]Isaac Newton

[edit]

Isaac Newton remarked in a letter to his rival Robert Hooke written in 5 February 1675 and published in 1855:

What Des-Cartes [sic] did was a good step. You have added much several ways, & especially in taking the colours of thin plates into philosophical consideration. If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.[14]

This has recently been interpreted by a few writers as a sarcastic remark directed at Hooke's appearance.[15] Although Hooke was not of particularly short stature, he was of slight build and had been afflicted from his youth with a severe kyphosis.

Others

[edit]Juan Luis Vives quotes the phrase "on shoulders of giants" in his De causis corruptarum artium (1531) with disapproval:

For it is a false and fond similitude, which some writers adopt, though they think it witty and suitable, that we are, compared with the ancients, as dwarfs upon the shoulders of giants. It is not so. Neither are we dwarfs, nor they giants, but we are all of one stature, save that we are lifted up somewhat higher by their means, provided that there be found in us the same studiousness, watchfulness and love of truth, as was in them. If these conditions be lacking, then we are not dwarfs, nor set on the shoulders of giants, but men of a competent stature, grovelling on the earth.[16]

Diego de Estella took up the quotation in 1578 and by the 17th century it had become commonplace. Robert Burton, in the second edition of The Anatomy of Melancholy (1624), quotes Stella thus:

I say with Didacus Stella, a dwarf standing on the shoulders of a giant may see farther than a giant himself.

Later editors of Burton misattributed the quotation to Lucan; in their hands Burton's attribution Didacus Stella, in luc 10, tom. ii "Didacus on the Gospel of Luke, chapter 10; volume 2" became a reference to Lucan's Pharsalia 2.10. No reference or allusion to the quotation is found there.[17]

In 1634, Marin Mersenne quoted the expression in his Questions harmoniques:

... comme l'on dit, il est bien facile, & mesme necessaire de voir plus loin que nos devanciers, lors que nous sommes montez sur leur espaules ...[18]

Blaise Pascal, in the "Preface to the Treatise on the Vacuum" expresses the same idea, without talking about shoulders, but rather about the knowledge handed down to us by the ancients as steps that allow us to climb higher and see farther than they could:

C'est de cette façon que l'on peut aujourd'hui prendre d'autres sentiments et de nouvelles opinions sans mépris et sans ingratitude, puisque les premières connaissances qu'ils nous ont données ont servi de degrés aux nôtres, et que dans ces avantages nous leur sommes redevables de l'ascendant que nous avons sur eux; parce que s'étant élevés jusqu'à un certain degré où ils nous ont portés, le moindre effort nous fait monter plus haut, et avec moins de peine et moins de gloire nous nous trouvons au-dessus d'eux. C'est de là que nous pouvons découvrir des choses qu'il leur était impossible d'apercevoir. Notre vue a plus d'étendue; et, quoiqu'ils connussent aussi bien que nous tout ce qu'ils pouvaient remarquer de la nature, ils n'en connaissaient pas tant néanmoins, et nous voyons plus qu'eux.[19]

Later in the 17th century, George Herbert, in his Jacula Prudentum (1651), wrote "A dwarf on a giant's shoulders sees farther of the two."

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in The Friend (1828), wrote:

The dwarf sees farther than the giant, when he has the giant's shoulder to mount on.

Against this notion, Friedrich Nietzsche argues that a dwarf (the academic scholar) brings even the most sublime heights down to his level of understanding. In the section of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1882) entitled "On the Vision and the Riddle", Zarathustra climbs to great heights with a dwarf on his shoulders to show him his greatest thought. Once there however, the dwarf fails to understand the profundity of the vision and Zarathustra reproaches him for "making things too easy on [him]self." If there is to be anything resembling "progress" in the history of philosophy, Nietzsche in "Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks" (1873) writes, it can only come from those rare giants among men, "each giant calling to his brother through the desolate intervals of time", an idea he got from Schopenhauer's work in Der handschriftliche Nachlass.[20]

Contemporary references

[edit]- NASA's official film of the Apollo 17 lunar landing mission was titled On the Shoulders of Giants.[21]

- Standing on the Shoulder of Giants is the title of the fourth studio album by English rock band Oasis. The title was actually a misquote by Noel Gallagher after seeing the quote on the British two pound coin while in a pub.[22]

- The British two pound coin bears the inscription STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS on its edge; this is intended as a quotation of Newton.[23]

- R.E.M. references the phrase in the chorus of their song "King Of Birds" - "Standing on the shoulders of giants leaves me cold"

- Stephen Hawking stated: "Each generation stands on the shoulders of those who have gone before them, just as I did as a young PhD student in Cambridge, inspired by the work of Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell and Albert Einstein."[24] Additionally, Hawking wrote a book called On the Shoulders of Giants, which explores the major works of physics and astronomy that inspired him.[25]

- Google Scholar, a search engine for academic literature, displays the phrase "Stand on the shoulders of giants" below the search field.[26][27]

- Umberto Eco writes in his 1980 novel The Name of the Rose, that Nicholas of Morimondo laments, "We no longer have the learning of the ancients, the age of giants is past!" To which the protagonist, William of Baskerville, replies: "We are dwarfs, but dwarfs who stand on the shoulders of those giants, and small though we are, we sometimes manage to see farther on the horizon than they."

See also

[edit]- Collective intelligence

- Derivative work

- Distributed cognition

- Great Conversation

- School of Chartres

- Stigler's law of eponymy

Notes

[edit]- ^ The meaning and origin of the expression: Standing on the shoulders of giants, The Phrase Finder.

- ^ Keith, Bonnie (2016). Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137552204. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Letter from Sir Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ Merton, Robert K. (1993). On the Shoulders of Giants. A Shandean Postscript. The Post-Italianate Edition. With a Foreword by Umberto Eco. University of Chicago Press. p. xiv.

- ^ Jeauneau, Édouard (2009). Rethinking the School of Chartres. Univ. of Toronto Press. p. 50.

- ^ Llano, Ignacio Cabello (31 May 2022). "«Como enanos a hombros de gigantes»: la frase atribuida a Bernardo de Chartres en su contexto (1159)". Fontes Medii Aevi (in Spanish). doi:10.58079/osqr.

- ^ Wirth, Karl August (1992). "Lateinische und deutsche Texte in einer Bilderhandschrift aus der Frühzeit des 15. Jahrhunderts". In Henkel, Nikolaus; Palmer, Nigel F. (eds.). Latein und Volkssprache im deutschen Mittelalter, 1100 - 1500 (in German). Max Niemeyer Verlag. pp. 256–295.

- ^ Castelberg, Marcus; Fasching, Richard F., eds. (2013). Die, Süddeutsche Tafelsammlung': Edition Der Handschrift Washington, D.C., Library of Congress, Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection, Ms. No. 4: 34 (in German). De Gruyter.

- ^ John of Salisbury (1159). Metalogicon. folio 217 recto (f 217r).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ MacGarry, Daniel Doyle, ed. (1955). The Metalogicon of John Salisbury: A Twelfth-century Defense of the Verbal and Logical Arts of the Trivium. Translated by MacGarry, Daniel Doyle. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 167.

- ^ Southern, Richard William (1952). Making of the Middle Ages. Yale University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0300002300.

- ^ Marjorie Chibnall (ed.), The Ecclesiastical History of Ordericus Vitalis, Oxford University Press, 1973 Bk.8, ch.7 p.238.

- ^ Teshuvot (responsa) haRid, responsum 62, columns 301–303. See Shnayer Z. Leiman, Dwarfs on the Shoulders of Giants, Tradition Spring 1993

- ^ Turnbull, H. W. ed., 1959. The Correspondence of Isaac Newton: 1661–1675, Volume 1, London, UK: Published for the Royal Society at the University Press. p. 416

- ^ Crease, Robert P. (2008). The Great Equations: The hunt for cosmic beauty in numbers. Constable and Robinson. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-84529-281-2.

- ^ Vives, Juan Luis; Watson, Foster (1913). Vives, on education : a translation of the De tradendis disciplinis of Juan Luis Vives. Cambridge : The University Press. pp. cv–cvi.

- ^ Estella, Diego (1582). "Caput. X". Enarrationes (tomus secundum) (in Latin). p. 24.

Bene tamen scimus pygmeos gigantum humeris impositos, plus quam ipsos gigantes videre.

- ^ Questions harmoniques, dans lesquelles sont contenuës plusieurs choses remarquables pour la physique, pour la morale, et pour les autres sciences (in French).

- ^ Pascal, Blaise (1887). Opuscules philosophiques, pub. avec une vie de Pascal (in French). Hachette et cie.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, Keith Ansell-Pearson, and Duncan Large. "Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks". The Nietzsche Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2006. 101–13. Print.

- ^ Service, NASA+ Streaming (31 October 2023). "Apollo 17: On the Shoulders of Giants". NASA+. Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ "Oasis - Official website". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- ^ "United Kingdom Two Pound Coin Design". Royal Mint. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (22 October 2017). "Stephen Hawking's 1966 doctoral thesis made available for first time". the Guardian.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen (2002). On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy. Running Press. ISBN 9780762416981.

- ^ "On the shoulders of giants: Why include data citations in research?". National Snow and Ice Data Center. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Standing on the shoulders of the Google giant: Sustainable discovery and Google Scholar's comprehensive coverage". Impact of Social Sciences. 19 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

References

[edit]- Jeauneau, Édouard (1973). Lectio philosophorum: recherches sur l'Ecole de Chartres. Hakkert.

- Jeauneau, Édouard (2009). Rethinking the School of Chartres. University of Toronto Press.

- Merton, Robert King; Eco, Umberto; Donoghue, Denis (1993). On the shoulders of giants: a Shandean postscript. University of Chicago press.

KSF

KSF