Steek (Sikh literature)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 12 min

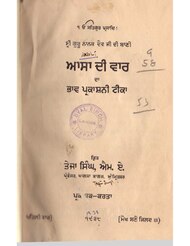

Teeka (exegesis) on the Sikh "Asa Di Vaar" Composition |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikh literature |

|---|

|

| Sikh scriptures • Punjabi literature |

A steek or teeka (other spellings may exist such as stik or tika) (Gurmukhi: ਸਟੀਕ, romanized: steek; 'Exegesis') is an exegesis or commentary on a Sikh religious text,[1][2] usually Gurbani, but can also include other writings like the ghazals of Bhai Nand Lal. An author of a steek or teeka is known as a teekakar (Gurmukhi: ਟੀਕਾਕਾਰ).[1] A steek always includes an explanation, or viakhya (Gurmukhi: ਵ੍ਯਾਖ੍ਯਾ)[1] of the specific religious text, but depending on the complexity of the steek, it can also include footnotes, commentary, and contexts to the specific verses and where they were first written/revealed (known as an "Uthanka" [Gurmukhi: ਉਥਾਨਕਾ]).

There are different characteristics and variations between steeks. Traditional Sikh commentaries on Sikh scripture are known as a Sampardai Steek/Teeka (Gurmukhi: ਸੰਪ੍ਰਦਾਈ ਟੀਕਾ/ਸਟੀਕ) and usually includes more detailed exegesis of Sikh Scripture.

Etymology

[edit]According to the Mahan Kosh, the word steek (ਸਟੀਕ) means "text with annotations, with the original text explanation,"[1] whereas the word teeka (ਟੀਕਾ) means "commentary on a granth (book), exegesis, 'read aloud with annotations.'"[1] Both words can trace their etymology to the Sanskrit language. A steek is typically a simpler translation of the text in question, whereas a teeka is typically held to be a more complex and in-depth exegesis of the religious text.

Categorization

[edit]There are four major types of Sikh scriptural interpretation techniques, they are as follows:[3]

- Teeka: commentary providing the meaning of a particular hymn or composition in layman's terms.[3] This technique is common amongst Sikh scholars.[3]

- Viakhia: extended commentary on a shabad.[3] This is the basic mode of scriptural exegesis performed at Sikh gurdwaras or deras.[3]

- Bhashya or bhash: an explanation of difficult words found in a text by the writer.[3]

- Paramarth: a glossary or "word-meanings", providing spiritual meanings of mystic and religious terms found in the scripture.[3]

History

[edit]The writings of Bhai Gurdas are considered to be the first exegeses of Sikh literature, and Bhai Gurdas is considered to be the first Sikh exegete (during the Guru Period).[4] His vaars provide in-depth commentary on Sikh theology. Later, in 1706, after the Battle of Muktsar, the army of Guru Gobind Singh camped at Sabo Ki Talwandi, today known as Takht Sri Damdamā Sahib.[5] That year, for nine months, Guru Gobind Singh performed oral exegesis of the Guru Granth Sahib, and this vidya is said to have been passed down the Sikh Sampardai.[6] In this way, traditional Sikh schools of thought (sampardai) are said to have received their knowledge and interpretations of scriptural canon from the pranali (lineage of knowledge).

There is also contemporary exegesis literature from the period that can be referenced today, such as the works of Bhai Mani Singh, which are often cited as sources for steeks.[7]

List of major Teekas and Steeks

[edit]Faridkot Teeka

[edit]When Western scholar Ernest Trumpp began to draft his English translation of the entire Sikh scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib, his approach earned him the disdain of many Sikhs.[8][9][10] Following the publication of Trumpp's work in 1877, Raja Bikram Singh, ruler of Faridkot (1842–98) and patron of the Amritsar Khalsa Diwan,[11] commissioned a full-scale commentary on the Guru Granth Sahib.[2] The revision was completed during the time of Raja Bikram Singh, but he did not live long enough to see publication of the work he had sponsored.[2] Four volumes of exegetical literature were later published (three volumes between 1905–06 and the fourth several years later[10]),[2] collectively known as the Faridkot Teeka,[12][13] due to its place of origin and exegetical nature. To this day, the Faridkot Teeka is held in high regard by many Sikhs, although many modern Sikh scholars and theologians have raised objections against the teeka, due to its Brahmanical and Vedantic leanings in explaining Sikh Theology.[2] Collectively, the teeka is over 4,000 pages of literature[14] and includes (at times) multiple arths [ਅਰਥ] (meanings) and uthankas for the various shabads (hymns) within the Guru Granth Sahib.

Shabadarath Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji

[edit]This commentary was published between 1936 and 1941.[10] It was mostly the work of Teja Singh.[10]

Santhya Sri Guru Granth Sahib

[edit]Seven volumes of commentary were published between 1958 and 1962 by Vir Singh, though the work was never finished.[10]

Garib Ganjini Teeka

[edit]The Garib Ganjini Teeka is one of the most renowned and respected commentaries within the Sikh tradition. The word "Garib Ganjini" means "to destroy ego", principally the ego of Udasi Scholar Anandghan.[2][15][16] It was authored by Kavi Santokh Singh, as a rebuttal to a work written the Udasi, who he claimed degraded the Japji Sahib and Guru Nanak.[2][15] Santokh Singh criticized Anandghan for his belief that Guru Nanak recognized 6 Gurus in succession within the Japji Sahib, as well as his esoteric interpretations of the meanings of the text.[15] The teeka only covers the Japji Sahib, and is approximately 180 pages.[17]

Sri Guru Granth Sahib Darpan

[edit]The Sri Guru Granth Sahib Darpan is a 10-volume exegetical work, with over 6,000 pages of literature in total.[18][10] The work is notable for its objective nature, achieved through Sahib Singh's (the teekakar) complete reliance on the grammar of the Guru Granth Sahib to derive meanings.[19][20] As such, this exegesis does not include uthankas. The Sri Guru Granth Sahib Darpan was published between 1962 and 1964.[20][10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Nabha, Bhai Kahan Singh. "Mahan kosh." (No Title) (1990).

- ^ a b c d e f g Virk, Hardev Singh. "Approaches to the Exegesis of Sri Guru Granth Sahib."

- ^ a b c d e f g Singh, Anoop (27 February 2005). "Part 4: Interpretations and Commentaries: A - Studies of Interpretive Traditions". A Bibliography of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji. Panthic Weekly. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Philosophical Reflections on Śabad (word): Event - Resonance - Revelation, Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair.

- ^ Dhillon, Dalbir (1988). Sikhism Origin and Development. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 152.

- ^ Singh, Nirbhai. Philosophy of Sikhism: Reality and its manifestations. Atlantic Publishers & Distri, 1990.

- ^ SGGS Academy (2019-01-13). Exegesis Of Akaal Ustat: SGGS Academy.

- ^ Hawley, John Stratton; Mann, Gurinder Singh, eds. (1993). Studying the Sikhs: issues for North America. SUNY series in religious studies. Albany, N.Y: State Univ. of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

- ^ Ballantyne, Tony (2006). Between colonialism and diaspora: Sikh cultural formations in an imperial world. Durham, N. C. London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3824-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g McLeod, William Hewat (11 August 2024). "Sikh literature". Britannica. Retrieved 25 August 2024.

- ^ Singh, Gurdarshan. "The Singh Sabha Movement." History and Culture of Punjab (1988): 95-107.

- ^ Macauliffe, Max Arthur, and Devinder Singh. "FORMULATING METHODOLOGY FOR INTERPRETING GURBANI."

- ^ McLeod, William Hewat, ed. Textual sources for the study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- ^ Gurubani. Fridkot Wala Teeka.

- ^ a b c Singh, Pashaura (2003). "5. Nirmala Pranali". The Guru Granth Sahib: Canon, Meaning and Authority. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199087730.

The origin of the Nirmala sect within the Panth is obscure, although there is some evidence that it existed during the Misal period in the late eighteenth century. There is no evidence to support the traditional claim that Guru Gobind Singh himself deputed five Sikhs to Kashi for Sanskritic learning. The first recognized Nirmala scholar was Kavi Santokh Singh, who wrote the celebrated works Nanak Prakash and Suraj Prakash in the first half of the nineteenth century. He also wrote a commentary on Japji, popularly known as Garbganjani Tika, 'A Commentary to Humble the Pride [of Udasi Anandghan].' Santokh Singh took strong exception to Anandghan's interpretation that Guru Nanak acknowledged six Gurus in a line from Japji. He was also strongly critical of the esoteric interpretation of gurbani presented in the Udasi work. It appears that the scriptural interpretation was one focus of conflict among various sects within the Panth in the nineteenth century. Like Udasis, however, the Nirmala scholars were equally inclined towards Vedantic interpretations of gurbani. They maintained that gurbani was essentially an expression of the Vedic teachings in the current vernacular language (bhakha). In his commentary on Japji, for instance, Santokh Singh frequently employed the Puranic myths and examples from the Vedas to make a point. Basically, he interpreted certain key Sikh doctrines from a brahminical perspective.

- ^ Mandair, Arvind (2009). Shared Idioms, Sacred Symbols, and the Articulation of Identities in South Asia. Volume 11 of Routledge Studies in Religion. Vol. 11. Michael Nijhawan, Kelly Pemberton. New York: Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-203-88536-9. OCLC 1082242146.

- ^ Kavi Santokh Singh. Garab Ganjinee Teeka - Searchable in Unicode - Punjabi - Vichar and Exegsis.

- ^ www.DiscoverSikhism.com. Sri Guru Granth Sahib Darpan (in Punjabi).

- ^ Singh, Devinder. "FORMULATING METHODOLOGY FOR INTERPRETING GURBANI POSSIBLE CAUSES AND/OR EXCUSES."

- ^ a b Staff, Anoop Singh-Panthic Weekly. "Bibliography of Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji."

KSF

KSF