Symphony (Webern)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

| Symphony, Op. 21 | |

|---|---|

| Symphony by Anton Webern | |

Incipit with labeled tone rows | |

| Opus | 21[1] |

| Period | die Neue Musik (20th-century music) |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1927–1928 |

| Dedication | Webern's youngest daughter Christine Mattl (née Webern)[2] |

| Duration | 10–20 minutes[3] |

| Movements | I. Ruhig schreitend II. Variationen |

| Scoring | 1 clarinet 1 bass clarinet 2 horns 1 harp strings without basses |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 18 December 1929 (world premiere) |

| Location | Town Hall, New York |

| Conductor | Alexander Smallens |

| Performers | Orchestra of the League of Composers |

Symphony, Op. 21 was composed by Anton Webern between 1927 and 1928. It was his first twelve-tone orchestral work.[4] The two-movement work lasts 10–20 minutes and is full of Alpine topics, abstraction, and intricate musical form, including some fixed register.[5][6] The Symphony was influenced by Gustav Mahler. Alexander Smallens conducted the world premiere at New York's Town Hall on 18 December 1929.

Historical background

[edit]Webern was an alpinist who enjoyed mountain excursions.[7] He loved the quiet otherworldliness of the altitude. He referred to these landscapes as "up there", a spiritual, utopian realm.[8] He continued Mahler's practice of portraying Alpine stillness and spaciousness in his music.[9]

His favorite mountain was the Schneealpe. Webern climbed it twice in 1928 while he was writing the Symphony, summiting only once in July. He also climbed the Hochschwab twice while he was composing the work.[10]

After finishing the Symphony, Webern wrote to the poet Hildegard Jone on 6 August 1928. Replying to her suggestion that "progress is made only inwards", he concurred, "I understand 'Art' to mean the faculty of bringing a thought into the clearest, simplest, i.e. 'most comprehensible' form." Pointing to previous masters like Beethoven, he continued, "...I have always only endeavoured to do exactly as they did: to represent as clearly as possible that which is given to me to say."[11]

Orchestration

[edit]Webern's Symphony is scored for clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 horns, harp, and strings without basses.[12] He was paring down his orchestration compared to his earlier work. In the same period, he was reducing the "extravagant" wind parts in Sechs Stücke, Op. 6.[13] In the summer of 1929, the League of Composers offered him $350 to premiere a chamber orchestra work. He suggested the newly published Symphony and indicated the strings could be performed solo despite the score markings. He confessed in his diary: "Better with multiple strings."[14]

The wind section of Webern's Symphony is limited to clarinets and horns. Both instruments have wide ranges and strong pastoral connections.[15] They are often paired together, and the horn is an archetypal symbol of wide Alpine space.[16]

Tone Row

[edit]Webern saw variations as "the primeval form" which yields "the most comprehensive unity". He pointed to the second Netherland school's use of canons as the simplest method of variation because "everyone sings the same thing", and a great deal of material can be generated through simple methods like reversing or inverting the melody.[17] Almost the entire Symphony is a series of canons, turning it into a kind of "essay in symmetry".[18]

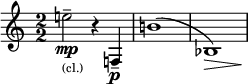

Webern used the same tone row for both movements. The material is even more cohesive because the second half of the row is derived from the first, a technique Webern relied on extensively.[19] The first six notes (hexachord) are transposed up a diminished fifth and reversed to generate the last six notes. These symmetries are part of what make the Symphony one of the most unified works of its type. Since it is a mirrored row, there are only 24 permutations instead of the usual 48.[20]

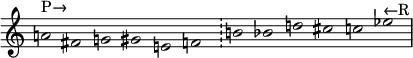

Symphony Op. 21 Tone Row

P: prime form. R: retrograde form.

I: inverted form. RI: retrograde inverted form.

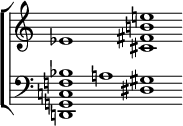

The tone row consists of the tetrachords [0,1,2,3] and [0,1,6,7]:

Its trichords are [0,1,3] and [0,1,4]:

Movements

[edit]The symphony is in two movements:

- I. Ruhig schreitend (Calmly paced)

- II. Variationen (Variations)

Webern initially planned three movements and sketched two iterations:[21]

- Rondo: lively—sun

- Variations: moderately

- Free form: very calmly—moon

- Variations

- Rondo (Scherzo, march-like)

- Slowly

Webern's first sketch for the symphony is dated November–December 1927. He finished the variations in March 1928. He wrote a canonic Adagio as the second movement that summer. He began drafting the third movement in August but quickly abandoned it. While deciding to jettison the third movement, Webern found comfort in the models of Beethoven's two-movement piano sonatas and Bach's two-movement orchestral suites. He also decided to reverse the movements, putting the adagio before the variations.[22]

I. Ruhig schreitend

[edit]The first movement consists of an inverted double canon with frequent palindromes.[23] Webern's experience in vocal writing predisposed him to compose linear, song-like material.[24] The first canon features lilting pastoral rhythms in the lower strings and Ländler-like horns. Webern's rhythms and orchestration for the second canon are less homogenous with ornaments, double stops, mutes, harmonics, pizzicati, and plucked harp. Eventually, the more chaotic second canon affects the character of the first.[25] Because the fitful canon is so attenuated and broadly dispersed among the instruments and their registers, it is difficult to perceive.[20][26]

Webern marshals his double canon into a rough sonata form with an exposition (mm. 1–26), development (mm. 25–44b), and recapitulation (mm.61–66). The sections are demarcated by tempo variations.[20] He innovates by introducing the two sonata themes simultaneously.[27] Webern also hearkens back to early sonatas by repeating both sections.[28] As the second canon finishes by itself, it functions as a kind of stretto.[29]

Exposition

[edit]Webern painstakingly sketched the first several bars through several iterations.[30] They are an archetypal example of klangfarbenmelodie. The texture is very sparse, but because of the constant timbre changes, the passage sounds dense.[31]

The symphony's opening is evocative of Mahler's Symphony No. 9 (1912). Webern enthused to Arnold Schoenberg that Mahler's Ninth was "inexpressibly beautiful". From Mahler's opening, Webern borrowed the texture of horns, harp, and low strings designed to evoke an Alpine expanse.[25] Both composers' tempo markings also allude to walking: Ruhig schreitend (calmly paced) and Andante comodo (comfortably walking).[32]

The opening horn call establishes a motif that is recognizable in subsequent phrases, even as the material is transposed and accelerated.[33]

- Opening horn fanfare, mm. 1–4

- First variant, mm. 6–8, clarinet

- Figure with acciaccatura, mm. 14–15, violin I

The motif is so strongly established that the row's tetrachords are highlighted and quite perceptible.[34] This emphasis is a counterpoint to the binary nature of the row.[20]

During the exposition, Webern limits the pitch space to a fixed register. The horn's opening A is the center of a symmetrical axis that expands outwards in increasing intervals, beginning with chromatic minor seconds and ending with fourths.[35] This organization of the musical space is another of the work's mirrors in that it reverses the interval relationships of the tonal overtone series.[26]

- Pitch space of the tone row centered on A (mm. 1–25)[35]

The pitch space can also be organized into two symmetrical columns of perfect fourths around the row's initial A.[36] Notably, both columns terminate in the only repeated note, E♭, which is also the terminal note in Webern's row.[37] Webern's conception of music was primarily linear.[38] Nevertheless, the D at the bottom of the pitch space has led some analysts to note the recurrence of D-major sonorities. Measure 13 begins with a major 10th D and F♯.[39] Webern's idyll Im Sommerwind centers on a slowly unfolded D-major triad.[40]

- Vertical arrangement of the tone row's pitch space (mm. 1–25)[36]

Development

[edit]

Webern expands the range of the piece to four and a half octaves in the development.[41] In fact, the development section ends on the highest note in the entire movement, a pianississimo 8th-note C♯ in the harp (mm. 45).[20] Webern's Fünf Geistliche Lieder also ends with a single, high, quiet harp harmonic.[42]

Webern continues developing the opening horn motif in the development. The shape is distorted but still recognizable. Illusions of tonality also persist in the development, particularly C major beginning in m. 27.[43]

Recapitulation

[edit]

Relative to that of the exposition, the music of the recapitulation is generally louder, quicker, and higher in pitch. It is more melodically fragmented, ornamented (with acciaccature), registrally expansive (by a tritone), rhythmically erratic, and timbrally varied (with harmonics and mutes) despite sharing the same tone-row structure.[44] The transmuted form of Webern's material is evident from the first statement of the recapitulation by the viola. It plays the same four notes the horn did to begin the piece, but their character is far removed from its atonal alpine call.[45]

In the stretto coda, the texture becomes leaner.[20] There are quick, shifting eighth-note figures of three to five pitches each (not including acciaccature), mostly in the violins and violas.[46] The horns play one note each.[46] The motivic material is reduced to a wisp of two notes and finally one muted tone marked with a diminuendo, an ending quite common in the slow movements of Romantic symphonies.[20]

II. Variationen

[edit]The second movement is a theme and variations with a coda. Webern indicates seven variations in the score, and each section is eleven bars for a total of 99 in the movement.[28]

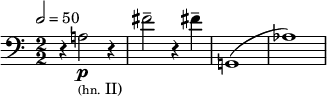

Unlike the relentlessly symmetrical fragmentation of the first movement, the theme of the second movement is stated entirely by the clarinet. The horns and the harp accompany by playing the theme in reverse, imitating a crab canon.[47] All of the variations are canons. The coda is sometimes seen as an additional variation.[48]

The fourth variation is a vague parody of the waltz and ländler.[49] It is also the midpoint of the entire movement. From there, Webern repeats the material in reverse. He described the movement as a double canon in retrograde motion.[50]

The harp's ostinato in the fifth variation was an imitation of cowbells. When Theodor Adorno recognized the allusion, Webern was "extremely happy".[51] Webern loved Mahler's use of almglocken particularly in the Nachtmusik of his Seventh Symphony. Webern's early orchestral works actually included cowbells in imitation of Mahler.[52]

There is another echo of Mahler in the violin solo that makes the last sustained statement in Webern's Symphony. It recalls the violin solo in the closing gesture of Mahler's Ninth Symphony.[53]

Tempo and total duration

[edit]The reported duration of Webern's Symphony varies substantially from approximately ten to perhaps as many as twenty minutes.[3] The published score gives a duration of ten minutes.[54] Webern wrote Schoenberg in September 1928 estimating "almost a quarter of an hour" for the first movement and "about six minutes" for the second, or "about twenty minutes of music" in total.[54] Conductors' approaches have varied significantly, but Webern's ideas about his music having a longer duration or slower tempi have generally not been realized in practice.[54] This problem is not exclusive to the Symphony, as Webern gave conductor Edward Clark estimates of seventeen minutes for the Op. 5 arrangement and ten minutes for the Op. 10 orchestral pieces, total durations nearly twice as long as what is the case in most performances.[54]

Reception

[edit]Premieres

[edit]Alexander Smallens and the Orchestra of the League of Composers gave the world premiere at New York's Town Hall on 18 December 1929, meeting jeers.[55] The New York Times ridiculed the piece as "one of those whispering, clucking, picking little pieces that Webern composes, when he whittles away at small and futile ideas, until he has achieved the perfect fruition of futility". They report, "The audience laughed it out of court..."[56] The same month, Webern wrote to Schoenberg that Otto Klemperer, Hermann Scherchen, and Leopold Stokowski had all expressed interest.[57]

At the Vienna Konzerthaus (1930), Webern himself conducted an ensemble including the Kolisch Quartet and members of the Wiener Staatsoper, flanking his Symphony with Brahms's Piano Quartet No. 2 (Eduard Steuermann, piano) and Beethoven's Septet. Josef Reitler wrote in the Neue Freie Presse that "barbaric ... soullessness is foreign [to Webern]", contrasting him with Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, and the Ernst Krenek of Jonny spielt auf.[58]

Listeners laughed in Berlin (April 1931), where Klemperer conducted.[59] He had only two weeks to prepare.[60] Heinz Tietjen was defunding the Krolloper ostensibly for its poorly attended modernist repertoire.[61]

Scherchen conducted the London premiere at the summer 1931 International Society for Contemporary Music Festival. Prompted by Schoenberg, Edward Clark had invited Webern to conduct. Webern declined, citing travel fatigue and his desire to focus on composition. There was also low remuneration, recent bad press, and as noted in his diary earlier that year: "Need for quiet and reflection."[62]

Klemperer programmed the Symphony again in 1936 Vienna, likely on Schoenberg's advice, but did not adhere to Webern's desired performance practice.[63]

Composers

[edit]Luigi Dallapiccola studied Schoenberg's and Webern's music especially after World War II.[64] He carefully read and published a review of René Leibowitz's Schoenberg et son école, which described Webern's techniques in the Symphony, like its double-inverted canons and palindromes.[65] Dallapiccola's subsequent music featured axial symmetry, canons, and four-part tone-row writing likely modeled in part on Webern's Symphony.[66] The Goethe-Lieder (1953) have palindromes.[67] An Mathilde (1954) features a tone-row form in each of four voices.[68] Parole di San Paolo (1964) and the second movement of Webern's Symphony both deploy a rest or fermata at their center (m. 50 in both cases).[69]

Karel Goeyvaerts noted proto-serial schemes of articulations, dynamics, and register in Webern's Symphony. Karlheinz Stockhausen applied the Symphony's tone row in Klavierstücke VII, IX, and X.[70] George Rochberg noted the "objectified, mensural" relation of pitch and time in Webern's later instrumental writing.[71]

References

[edit]- ^ Webern 1929, 1.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 480; Webern 1929, 2.

- ^ a b Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 326; Näf 2019, 180–194; Webern 1929, 16.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 2; Johnson 1999, 200.

- ^ Johnson 1999, 74 106, 205; Morris 2016, 74–81, 119–120, 170–174.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 154, 197, 202.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 302.

- ^ Peattie 2015, 103.

- ^ Johnson 1999, 30, 33.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 257, 301–2.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 342.

- ^ Webern 1929.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 128–129, 325.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 326–327, 344.

- ^ Hoeprich 2021, 12–16.

- ^ Johnson 1999, 53, 205.

- ^ Webern 1963, 40, 53.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 95.

- ^ Babbitt 1987, 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown 2003, 876.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 324.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 324–326.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 95-6.

- ^ Shreffler 1994, 18.

- ^ a b Spitzer 2020, 350–351.

- ^ a b Döhl 1976, 247.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, p. 155: Bailey also summarizes competing analyses of the first movement's form (pp. 66–7).

- ^ a b Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 325.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 170.

- ^ Shreffler 1994, 42.

- ^ Adler 1989, 506–8.

- ^ Johnson 1999, 205.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 165–166, paraphrasing Wolfgang Martin Stroh.

- ^ Hanninen 2012, 81–2.

- ^ a b McKenzie 1960, 403–4.

- ^ a b Borris 1966, 236.

- ^ Schulenberg 1985, 236.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 334.

- ^ Fürbeth 1998, 582.

- ^ Puffett 2001, 529.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 167.

- ^ Johnson 1999, 156–157.

- ^ Stroh 1975, 26–8.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 164, 168–169.

- ^ Stroh 1975, 29.

- ^ a b Borris 1966, 237.

- ^ Bailey Puffett 1991, 99–100.

- ^ Craft 2004.

- ^ Hood 2022, 172.

- ^ Webern 1963, 56.

- ^ Hood 2022, 170.

- ^ Peattie 2015, 102–3, 113.

- ^ Fürbeth 1998, 584.

- ^ a b c d Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 326.

- ^ Miller 2022b, "The rule"; Morgan 1993, 416.

- ^ Downes 1929.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 305.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 344.

- ^ Heyworth 1983, 246.

- ^ Heyworth 1983, 362; Moskovitz 2010, 256.

- ^ Moskovitz 2010, 249-251.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 362–364.

- ^ Moldenhauer and Moldenhauer 1978, 470–471, 679–680.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 29.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 29–30.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 30, 48, 162, 193, 293n20.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 293n20, 302n34.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 4, 162, 193.

- ^ Alegant 2010, 5, 307n7.

- ^ Maconie 2016, 38, 127, 195–196.

- ^ Rochberg 2004, 15.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adler, Samuel. The Study of Orchestration. Norton, 1989.

- Alegant, Brian. 2010. The Twelve-tone Music of Luigi Dallapiccola. Vol. 76, Eastman Studies in Music, sen. ed. Ralph P. Locke. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-325-6 (hbk).

- Babbitt, Milton. 1987. Words about Music: The Madison Lectures, eds. Stephen Dembski and Joseph N. Straus. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-10790-1 (hbk).

- Bailey Puffett, Kathryn. 1991. The Twelve-Note Music of Anton Webern: Old Forms in a New Language. Music in the Twentieth Century, gen. ed. Arnold Whittall. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39088-0 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-521-54796-3 (pbk).

- Borris, Siegfried. 1966. "Structural Analysis of Webern's Symphony Op. 21", trans. Ursula Klein. In Paul A. Pisk: Essays in his Honor, ed. John M. Glowacki, fwd. E. W. Doty. Austin: The University of Texas Press.

- Brown, A. Peter. 2003. The Second Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Brahms, Bruckner, Dvořák, Mahler, and Selected Contemporaries. Vol. 4, The Symphonic Repertoire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33488-6 (hbk).

- Döhl, Friedhelm. 1976. Weberns Beitrag zur Stilwende der Neuen Musik: Studien über Voraussetzungen, Technik und Ästhetik der "Komposition mit 12 nur aufeinander bezogenen Tönen". Vol. 12, Berliner Musikwissenschaftliche Arbeiten, gen. eds. Carl Dahlhaus and Rudolf Stephan. Munich and Salzburg: Emil Katzbichler. ISBN 978-3-87-397042-7 (pbk).

- Downes, Olin. "Music: The League of Composers", The New York Times. 19 December 1929. 31.

- Ellsworth, Jane. 2021. "From 'Little Trumpet' to Unique Voice: The Clarinet in the Concert Orchestra". The Clarinet, ed. Jane Ellsworth. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-80010-350-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-64825-017-0 (hbk).

- Fink, Robert. 1993. "Desire, Repression & Brahms's First Symphony". repercussions. 2(1):75–103.

- Fürbeth, Oliver. 1998, 29 September–4 October. "Die Frage nach dem 'Ausdruck' im Spätwerk Anton Weberns". [Conference presentation]. Internationalen Kongreß der Gesellschaft für Musikforschung Halle (Saale). Musikkonzepte — Konzepte der Musikwissenschaft 2, 580–585, eds. Kathrin Eberl and Wolfgang Ruf. Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISBN 978-3-76-181536-6 (pbk). Republished 1999. Musik & Ästhetik. 3(11):43–50. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta. Digitally published 2019. Dresden: Qucosa.

- Hanninen, Dora A. 2012. A Theory of Music Analysis: On Segmentation and Associative Organization. Vol. 92, Eastman Studies in Music, sen. ed. Ralph P. Locke. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-194-8 (hbk).

- Heyworth, Peter. 1983. Otto Klemperer: His Life and Times, Vol. I: 1885–1933. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Reissued with corrections, 1996. ISBN 978-0-521-49509-7 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-521-39088-0 (hbk).

- Hiller, Lejaren, and Ramon Fuller. "Structure and Information in Webern's Symphonie, Op. 21". Journal of Music Theory. 11(1):60–115. Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/842949.

- Hoeprich, Eric. 2021. "Clarinet Iconography". The Clarinet, ed. Jane Ellsworth. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-80010-350-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-64825-017-0 (hbk).

- Hood, Danielle. 2022. The Viennese Waltz: Decadence and the Decline of Austria's Unconscious. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-79-365393-2 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-79-365392-5 (hbk).

- Johnson, Julian. 1999. Webern and the Transformation of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66149-2.

- Johnson, Julian. 2015. Out of Time: Music and the Making of Modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-023327-3. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190233273.001.0001.

- Kolneder, Walter. 1968. Anton Webern: An Introduction to His Works. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Trans. Humphrey Searle. (Translation of Anton Webern, Einführung in Werk und Stil. Rodenkirchen: P. J. Tonger, 1961.) ISBN 978-0-520-34715-1.

- Krones, Hartmut. 2007. "Webern, Anton Friedrich Wilhelm". MGG Online (accessed 31 Oct. 2024).

- Maconie, Robin. 2016. Other Planets: The Complete Works of Karlheinz Stockhausen, 1950–2007. Updated edition. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-44-227268-2 (electronic).

- McKenzie, Wallace Chessley. The Music of Anton Webern, dissertation, May 1960; Denton, Texas. North Texas State College.

- Miller, David H. 2022. "Shadows, wraiths, and amoebas: the distinctive flops of Anton Webern in the United States". Transposition. 10. École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) and the Cité de la musique-Philharmonie de Paris. (30 May, accessed 19 Jan. 2024)

- Moldenhauer, Hans, and Rosaleen Moldenhauer. 1978. Anton von Webern: A Chronicle of His Life and Work. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 978-0-394-47237-9.

- Morgan, Robert P. 1993. Modern Times: From World War I to the Present. Man & Music Series; Vol. 8. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-11291-3 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-349-11293-7 (hbk).

- Morris, Christopher. 2016. Modernism and the Cult of Mountains: Music, Opera, Cinema. Ashgate Interdisciplinary Studies in Opera. Oxford and New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-75466-970-8 (hbk). Reprint from original in 2012 by Ashgate Publishing.

- Moskovitz, Marc. 2010. Alexander Zemlinsky: A Lyric Symphony. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-84383-578-3.

- Näf, Lukas. 2019. "Tempogestaltung in Weberns Sinfonie op. 21." In Rund um Beethoven: Interpretationsforschung heute, eds. Thomas Gartmann and Daniel Allenbach, 180–194. Musikforschung der Hochschule der Künste Bern, Vol. 14. Schliengen: Edition Argus. ISBN 978-3-931264-94-9. doi:10.26045/kp64-6178.

- Peattie, Thomas. 2015. Gustav Mahler's Symphonic Landscapes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02708-4 (hbk).

- Derrick Puffett on Music, edited by Kathryn Bailey Puffett, Taylor & Francis Group, 2001.

- Rice, Albert R. 2021. "The Chalumeau and Clarinet before Mozart". The Clarinet, ed. Jane Ellsworth. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-80010-350-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-64825-017-0 (hbk).

- Rushton, Julian. 2021. "The Clarinet in Nineteenth-Century Opera". The Clarinet, ed. Jane Ellsworth. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-80010-350-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-64825-017-0 (hbk).

- Rochberg, George. 2004. The Aesthetics of Survival: A Composer's View of Twentieth-Century Music. Revised, expanded, and reprinted from original in 1984. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-02511-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-472-03026-2 (pbk).

- Seldes, Barry. 2009. Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94307-0.

- Service, Tom. 2013. "Symphony Guide: Webern's Op 21". Tom Service on Classical Blog. The Guardian.com (17 Dec., accessed 19 Jan. 2024).

- Shreffler, Anne C. 1994. Webern and the Lyric Impulse: Songs and Fragments on Poems of Georg Trakl, ed. and preface by Lewis Lockwood. Studies in Musical Genesis and Structure Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816224-7.

- Schulenberg, David. 1985. "Modes, Prolongations, and Analysis". Journal of Musicology. 4(3):303–329. University of California Press. doi:10.2307/763760.

- Spitzer, Michael. 2020. A History of Emotion in Western Music: A Thousand Years from Chant to Pop. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-006176-0.

- Starr, S. Frederick. 2021. "The Clarinet in Vernacular Music". The Clarinet, ed. Jane Ellsworth. Rochester: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-80010-350-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-64825-017-0 (hbk).

- Stroh, Wolfgang Martin. Webern: Symphonie op. 21. Meisterwerke der Musik, ed. Ernst Ludwig Waeltner, Vol. 11. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1975.

- Webern, Anton. 1929. Symphonie. Reprinted 1956. Vienna: Universal Edition.

- Webern, Anton. Symphony; Six pieces; Concerto for 9 instruments. Robert Craft, Liner Notes. Naxos, 2004.

- Webern, Anton. 1963. The Path to the New Music, ed. Willi Reich, trans. Leo Black. Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Theodore Presser Co., in Association with Universal Edition. Reprinted London: Universal Edition, 1975. Trans. of Der Wege zur neuen Musik, Vienna: Universal Edition, 1960.

- Wingfield, Nancy Meriwether. "When Film Became National: 'Talkies' and the Anti-German Demonstrations of 1930 in Prague". Austrian History Yearbook. 29(1):113–138. Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota. Published online in 2015 by Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/S006723780001482X.

Further reading

[edit]- Lynn, Donna. "12-Tone Symmetry: Webern’s Thematic Sketches for the Sinfonie, Op. 21, Second Movement." The Musical Times, vol. 131, no. 1774, 1990, pp. 644–46.

- Nelson, Robert U. "Webern's Path to Serial Variation", Perspectives of New Music, vol. 7, no. 2, 1969, pp. 73–93.

- Pace, Ian. 2022. "New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices." In The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance, Vol. 1, ed. Gary E. McPherson, 396-455. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190056-31-5 (online). ISBN 978-0-190056-28-5 (print). doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190056285.013.19.

- Starr, Mark. "Webern’s Palindrome." Perspectives of New Music, vol. 8, no. 2, 1970, pp. 127–42.

External links

[edit]- Symphony: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Symphony at AllMusic

KSF

KSF

![\new Staff \with { \remove "Time_signature_engraver" \remove "Bar_engraver" } \relative c' { \clef treble \override Stem #'transparent = ##t \accidentalStyle dodecaphonic <fis g gis a>1^\markup { \teeny [0,1,2,3] } <bes b f e>^\markup { \teeny [0,1,6,7] } <c cis d ees>^\markup { \teeny [0,1,2,3] } }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/y/sybuycv30r89k7xu0cnm388qxwciqd5/sybuycv3.png)

![\new Staff \with { \remove "Time_signature_engraver" \remove "Bar_engraver" } \relative c' { \clef treble \override Stem #'transparent = ##t \accidentalStyle dodecaphonic <fis g a>1^\markup { \teeny [0,1,3] } <e f gis>^\markup { \teeny [0,1,4] } <bes' b d>^\markup { \teeny [0,1,4] } <c cis ees>^\markup { \teeny [0,1,3] } }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/t/htqza8znr3ph83hzsirhi665znqcwq4/htqza8zn.png)