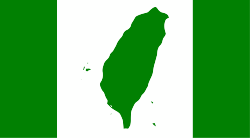

Taiwanese nationalism

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 10 min

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (January 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Taiwanese nationalism (Chinese: 臺灣民族主義,台湾民族主义; pinyin: Táiwān Mínzú Zhǔyì; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tâi-oân bîn-cho̍k-chú-gī) is a nationalist political movement that promotes the cultural identity and unity of Taiwanese people as a nation. In recent decades, it consists of cultural or political movements that seek to resolve the current political and social division on the issues of Taiwan's national identity, political status, and political dispute with China. It is closely linked to the Taiwan independence movement but distinguished from it in that the independence movement seeks to eventually establish an independent "Republic of Taiwan" in place of or out of the existing Republic of China and obtain United Nations and international recognition as a sovereign state, while nationalists seek only to establish or reinforce an independent Taiwanese identity that distinguishes Taiwanese people apart from the Chinese nation, without necessarily advocating changing the official name of the country.

ROC independence or Taiwan independence

[edit]

Taiwanese nationalist camp is largely divided into ROC independence (abbreviated Huadu) and Taiwan independence (abbreviated Taidu). While supporters of Taiwan independence seek to establish a "Republic of Taiwan" rather than the Republic of China, but ROC independence supporters support two Chinas that strengthen their Taiwanese identity while distinguishing the "Republic of China" from the People's Republic of China.

Taiwanization

[edit]Taiwanization is a conceptual term used in Taiwan to emphasize the importance of a Taiwanese culture, society, economy, nationality, and identity rather than to regard Taiwan as solely an appendage of China. In the domestic dispute over the role of Taiwanization, Chinese nationalists in Taiwan argue that Taiwanese culture should only be emphasized in the larger context of Chinese culture, while Taiwanese nationalists argue that Chinese culture is only one part of Taiwanese culture.[1]

Taiwanese nationalist political parties

[edit]- Taiwanese People's Party (1927–1931)

- Taiwanese Communist Party (1928–1931)

- Democratic Progressive Party (1986–present)

- Taiwan Independence Party (1996–2020)

- Taiwan Solidarity Union (2001–present)

- New Power Party (2015–present)

- Free Taiwan Party (2015–present)

- Taiwan Statebuilding Party (2016–present)

See also

[edit]- 1025 rally to safeguard Taiwan / 517 Protest

- Desinicization

- February 28 Incident

- Formosa Alliance

- Han Taiwanese nationalism

- History of Taiwan

- Hong Kong nationalism

- Pro-Taiwanese sentiment

- Qiandao Lake Incident

- Seediq Bale

- Sinicization

- Sinocentrism

- Taiwan nativist literature

- Taiwan Number One

- Taiwanese literature movement

- Taiwanese Localism Front

- Taiwanese nationalism in Taiwan under Japanese rule

- Third Taiwan Strait Crisis

References

[edit]- ^ Ching Cheong; Xiang Cheng; Cheong Ching (2001). Will Taiwan Break Away: The Rise of Taiwanese Nationalism. ISBN 981024486X.

2. Tzeng, Shih-jung, 2009. From Honto Jin to Bensheng Ren- the Origin and Development of the Taiwanese National Consciousness, University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-4471-6.

KSF

KSF