Tamil culture

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 43 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 43 min

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

|

|

Tamil culture refers to the culture of the Tamil people. The Tamils speak the Tamil language, one of the oldest languages in India with more than two thousand years of written history.

Archaeological evidence from the Tamilakam region indicates a continuous history of human occupation for more than 3,800 years. Historically, the region was inhabited by Tamil-speaking Dravidian people. It was ruled by various kingdoms such as the Sangam period (3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE) triumvirate of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas, the Pallavas (3rd–9th century CE), and the later Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th century CE). European colonization began in the 17th century CE, and continued for two centuries until the Indian Independence in 1947. Due to its long history, the culture has seen multiple influences over the years and have developed diversely.

The Tamils had outside contact in the form of diplomatic and trade relations with other kingdoms to the north and with the Romans since the Sangam era. The conquests of Tamil kings in the 10th century CE resulted in Tamil culture spreading to South and Southeast Asia. Tamils form the majority in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu and a significant portion of northern Sri Lanka. Tamils have migrated world-wide since the 19th century CE and a significant population exists in Sri Lanka, South Africa, Mauritius, Reunion Island, Fiji, as well as other regions such as the Southeast Asia, Middle East, Caribbean and parts of the Western World.

History

[edit]Tamilakam was the region inhabited by the ancient Tamil people.[1] While archaeological evidence points to hominids inhabiting the region nearly 400 millennia ago, it has been inhabited by modern humans continuously for more than 3,800 years.[2][3][4] Excavations at Keezhadi have revealed urban settlements dating to the 6th century BCE.[5] The Tamilakam region has been ruled over by many kingdoms, major of which are the Sangam era (3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE) rulers of the Chera, Chola, and Pandya clans,[6][1] the Pallavas (3rd–9th century CE),[7] and the later Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th century CE).[8] The kingdoms had significant diplomatic and trade contacts with other kingdoms to the north and with the Romans.[9][10] In the 11th century CE, the Chola empire expanded with the conquests of parts of present-day Sri Lanka and Maldives, and increased influence across the Indian Ocean with contacts in Southeast Asia.[11][12] This resulted in Tamil influence spreading to the regions.[13]

Before mid 20th century, the regions populated by Tamils were under European colonization for more than two centuries.[14] During the European occupation, Tamils migrated and settled in various regions across the globe.[15][16] This resulted in significant Tamil population in Southeast Asia, Caribbean, South Africa, Mauritius, Seychelles and Fiji.[17] Since the 20th century, Tamils have migrated to other regions such as Middle East and the Western World for employment.[18][19][17] Tamils form the majority in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu and in northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka.[20][21]

Language

[edit]

Tamil people speak Tamil, which belongs to the Dravidian languages and is one of the oldest classical languages.[22][23][24] According to epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan, the rudimentary Tamil Brahmi script originated in South India in the 3rd century BCE.[25][26] Though the old Tamil preserved features of Proto-Dravidian language,[27] modern-day spoken Tamil uses loanwords from other languages such as English.[28][29] The existent Tamil grammar is largely based on the grammar book Naṉṉūl which incorporates facets from the old Tamil literary work Tolkāppiyam.[30] The Tamil grammar is classified into five divisions, namely eḻuttu (letter), sol (word), poruḷ (content), yāppu (prosody), and aṇi (figure of speech).[31][32] Since the later part of the 19th century, Tamils made the language as a key part of the Tamil identity and personified the language in the form of Tamil̲taay ("Tamil mother").[33] Various varieties of Tamil is spoken across regions such as Madras Bashai, Kongu Tamil, Madurai Tamil, Nellai Tamil, Kumari Tamil and various Sri Lankan Tamil dialects such as Batticaloa Tamil, Jaffna Tamil and Negombo Tamil in Sri Lanka.[34][35]

Literature

[edit]

Tamil literature is of considerable antiquity compared to the contemporary literature from other Indian languages and represents one of the oldest bodies of literature in South Asia.[36][37] The earliest epigraphic records have been dated to around the 3rd century BCE.[38] Early Tamil literature was composed in three successive poetic assemblies known as Tamil Sangams,[39][40] the earliest of which destroyed by floods.[41][42] The Sangam literature was broadly classified into three divisions: iyal (poetry), isai (music) and nadagam (drama). There are no surviving works from the later two categories and literature from the first category were further classified into illakkanam (grammar) and ilakkiyam (poetry).[43] The sangam literature was broadly based on two genres, akam (internal) and puram (external) described on the five landscapes.[44][45]

The oldest surviving book is the Tolkappiyam, a treatise on Tamil grammar.[36][46][47] The early Tamil literature was compiled and classified into two categories: Patinenmelkanakku ("Eighteen Greater Texts") consisting of the Ettuttokai ("Eight Anthologies") and the Pattuppattu ("Ten Idylls"), and the Patinenkilkanakku ("Eighteen Lesser Texts").[48][49] The Tamil literature that followed in the next 300 years after the Sangam period is generally called the "post-Sangam" literature which included the Five Great Epics and the Five Minor Epics.[42][49][50][51] Another book of the post Sangam era is the Tirukkural, a book on ethics, by Thiruvalluvar.[52]

In the beginning of the middle age, Vaishnava and Shaivite literature became prominent following the Bhakti movement in 7th century CE with hymns composed by Alwars and Nayanmars.[53][54][55] Notable work from the post-Bhakti period included Ramavataram by Kambar in 12th century CE and Tiruppugal by Arunagirinathar in 15th century CE.[56][57] In 1578, the Portuguese published a Tamil book in old Tamil script named Thambiraan Vanakkam, thus making Tamil the first Indian language to be printed and published.[58] Tamil Lexicon, published by the University of Madras between 1924 and 1939, was amongst the first comprehensive dictionaries published in the language.[59][60] The 19th century gave rise to Tamil Renaissance and writings and poems by authors such as Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, U.V.Swaminatha Iyer, Damodaram Pillai, V. Kanakasabhai and others.[61][62][63] During the Indian Independence Movement, many Tamil poets and writers sought to provoke national spirit, notably Bharathiar and Bharathidasan.[64][65]

Art and architecture

[edit]According to Tamil literature, there are 64 art forms called aayakalaigal.[66][67] The art is classified into two broad categories: kavin kalaigal (beautiful art forms) which include architecture, sculpture, painting and poetry and nun kalaigal (fine art forms) which include dance, music and drama.[68]

Architecture

[edit]

Dravidian architecture style of temple architecture consisted of a central sanctum (garbhagriha) topped by pyramidal tower or vimana, porches or mantapas preceding the door leading to the sanctum and large gate-pyramids or gopurams on the quadrangular enclosures that surround the temple. Besides these, they consisted of large pillared halls and one or more water tanks or wells.[69][70] The gopuram is a monumental tower, usually ornate at the entrance of the temple forms a prominent feature of Hindu temples of the Dravidian style.[70][71][72] They are topped by kalasams (finials) and function as gateways through the walls that surround the temple complex.[73]

There are a number of early rock-cut cave-temples established by the various Tamil kingdoms.[74][75][76] The Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram, built by the Pallavas in the 7th and 8th centuries has more than forty rock-cut temples, monoliths and rock reliefs.[77][78][79] The Pallavas, who built the group of monuments in Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram, were one of the earliest patronisers of the Dravidian architectural style.[77][80] These gateways became regular features in the Cholas and the Pandya architecture, was later expanded by the Vijayanagara and the Nayaks and spread to other parts such as Sri Lanka.[81][82][83] Madurai (also called as "Temple city"), which hosts many temples including the massive Meenakshi Amman Temple and Kanchipuram, considered as one of the seven great holy cities are amongst the notable centres of Dravidian architecture.[84][85] The Srirangam Ranganathaswamy Temple, which is amongst the biggest functioning Hindu temples in the world, has a 236 feet (72 m) high Rajagopuram.[86] The state emblem also features the Lion Capital of Ashoka with an image of a Gopuram on the background.[87][88]

Vimana, which are similar structures built over the inner sanctum of the temple are usually smaller than the gopurams in the Dravidian architecture with a few exceptions such as the Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur.[89][90][91] There are more than 34,000 temples in Tamil Nadu built across various periods some of which are several centuries old.[92] The influence of Tamil culture had led to the construction of various temples outside India by the Tamil dispora.[93][94]

The Mugal influence in medieval times and the British influence later gave rise to a blend of Hindu, Islamic and Gothic revival styles, resulting in the distinct Indo-Saracenic architecture with several institutions during the British era following the style.[95][96][97] By the early 20th century, the art deco made its entry upon in the urban landscape.[98] In the later part of the century, the architecture witnessed a rise in the modern concrete buildings.[99][100]

Sculpture and paintings

[edit]

Tamil sculpture ranges from stone sculptures in temples, to detailed bronze icons.[102] The bronze statues of the Cholas are considered to be one of the greatest contributions of Tamil art.[103] Models made of a special mixture of beeswax and sal tree resin were encased in clay and fired to melt the wax leaving a hollow mould, which would then be filled with molten metal and cooled to produce bronze statues.[104]

Tamil paintings are usually centered around natural, religious or aesthetic themes.[105] Sittanavasal is a rock-cut monastery and temple attributed to Pandyas and Pallavas which consist of frescoes and murals from the 7th century CE, painted with vegetable and mineral dyes in over a thin wet surface of lime plaster.[106][107][108] Similar murals are found in temple walls, the most notable examples are the murals on the Ranganathaswamy Temple at Srirangam and the Brihadeeswarar temple at Thanjavur.[109][110][111] One of the major forms of Tamil painting is Thanjavur painting, which originated in the 16th century CE where a base made of cloth and coated with zinc oxide is painted using dyes and then decorated with semi-precious stones, as well as silver or gold threads.[112][113]

Music

[edit]

The ancient Tamil country had its own system of music called Tamil Pannisai.[114] Sangam literature such as the Silappatikaram from 2nd century CE describes music notes and instruments.[115][116] A Pallava inscription dated to the 7th century CE has one of the earliest surviving examples of Indian music in notation.[117][118] The Pallava inscriptions from the period describe the playing of string instrument veena as a form of exercise for the fingers and the practice of singing musical hymns (Thirupadigam) in temples. From the 9th century CE, Shaivite hymns Thevaram and Vaishnavite hymns (Tiruvaymoli) were sung along with playing of musical instruments. Carnatic music originated later which included rhythmic and structured music by composers such Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri.[119][120] Villu Paatu is an ancient form of musical story-telling method where narration is interspersed with music played from a string bow and accompanying instruments.[121][122] Gaana, a combination of various folk musics is sung mainly in Chennai.[123]

There are many traditional instruments from the region dating back to the Sangam period such as parai,[124] tharai,[125] yazh,[126] and murasu.[127][128] Nadaswaram, a reed instrument that is often accompanied by the thavil, a type of drum instrument are the major musical instruments used in temples and weddings.[129] Melam is from a group of percussion instruments from the ancient Tamilakam which are played during events and functions.[130][131][132]

Tyagaraja Aradhana is an annual music festival conducted in Tiruvaiyaru, devoted to composer Tyagaraja where thousands of music artists congregate every year.[133] In the Tamil month of Margazhi, music concerts (katcheris) are generally conducted, popular of which include the Madras Music Season by the Madras Music Academy and Chennaiyil Thiruvaiyaru.[134][135][136]

Dance

[edit]

Bharatanatyam is a major genre of Indian classical dance that originated from Tamil Nadu and practiced till today.[137][138][139][140] It is one of the oldest classical dance forms of India.[141][142] The dancer is usually dressed in a colorful silk sari with various jewelry, special anklets called salangai made up of small bells and hair plaited in a specific manner, decorated with flowers in a pattern called veni.[143][144][145] The dance is characterized by flexing of torso with bent legs or flexed out knees combined with various footwork and a number of gestures known as abhinaya using various hand mudras, expressions using the eyes and other face muscles.[137][146]

There are many folk dance forms that originated and are practiced in the region. Karakattam involves dancers balancing decorated pot(s) on the head while making dance movements with the body.[147][148][149] Kavadiattam is part of a ceremonial act of sacrifice, wherein the dancers bear a kavadi, an arch shaped wooden stick balanced on the shoulders with weights on both the ends.[150][151] Kolattam is usually performed by women in which two small sticks (kols) are crisscrossed to make specific rhythms while singing songs.[152][153][154] Kummi is similar to Kolattam, with the difference being that hands are used to make sounds while dancing instead of sticks used in the later.[155][156] In Mayilattam, dancers dressed like peacocks with peacock feathers and headdresses perform movements to various folk songs and tunes while trying to imitate the movements of a peacock.[157][158]

Oyilattam, a traditional war dance where few men wearing ankle bells would stand in a line with pieces of colored cloth perform rhythmic steps to the accompanying music.[159][160][161] Paampu attam is a snake dance performed by young girls, who wear specifically designed costumes like a snake skin and emulate movements of a snake.[162][163] Paraiattam is a traditional dance that involves dancing while playing the parai, an ancient percussion instrument.[164][165] Puliyattam is performed by male dancers who paint themselves in yellow and black and wear masks, fuzzy ears, paws, fangs and a tail, and perform movements imitating a tiger.[166][167] Puravaiattam involves dancers getting into a wooden frame designed like the body of a horse on his/her hips and make prancing movements.[168][169] Other folk dances include Bhagavatha nadanam, Chakkaiattam, Devarattam, Kai silambattam, Kuravanji, Sevaiattam and Urumiattam.[170][171]

Performance arts

[edit]

Koothu is a form of street theater that consists of a play performance which consists of dance along with music, narration and singing.[172] The performers wear elaborate wooden headgear, special costumes with swirling skirts, ornaments such as heavy anklets along with prominent face painting and make-up. The art is performed during festivals in open public places and is usually dedicated to goddesses such as Mariamman or Draupadi with stories drawn from Hindu epics, mythology and folklore. The dance is accompanied by music played from traditional instruments and a kattiyakaran narrates the story during the performance.[173]

Bommalattam is a type of puppetry that uses various doll marionettes manipulated by rods and strings attached to them.[174][175] The puppeteers operate the puppets behind a screen illuminated by oil lamps and wear bells which are sounded along with the movements with background music played by traditional instruments. The themes are drawn from various Hindu scriptures such as the Puranas and epics and/with local folklore.[176] Chennai Sangamam is a large annual open Tamil cultural festival held in Chennai with the intention of rejuvenating the old village festivals, art and artists.[177]

Martial arts

[edit]

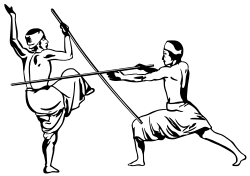

Silambam is a martial art using a long staff of about 168 cm (66 in) in length, often made of wood such as bamboo.[178][179] It was used for self-defense and to ward off animals and later evolved into a martial art and dance form.[180] Adimurai (or Kuttu varisai) is a martial art specializing in empty-hand techniques and application on vital points of the body.[181][182][183] Varma kalai is a Tamil traditional art of vital points which combines alternative medicine and martial arts, attributed to sage Agastiyar and might form part of the training of other martial arts such as silambattam, adimurai or kalari.[184] Malyutham is the traditional form of combat-wrestling.[181][185]

Tamil martial arts uses various types of weapons such as valari (iron sickle), maduvu (deer horns), vaal (sword) and kedayam (shield), surul vaal (curling blade), itti or vel (spear), savuku (whip), kattari (fist blade), aruval (mchete), silambam (bamboo staff), kuttu katai (spiked knuckleduster), kathi (dagger), vil ambu (bow and arrow), tantayutam (mace), soolam (trident), valari (boomerang), chakaram (discus) and theepandam (flaming baton).[186][187] Since the early Sangam age, war was regarded as an honourable sacrifice and fallen heroes and kings were worshipped with hero stones and heroic martyrdom was glorified in ancient Tamil literature.[188]

Modern arts

[edit]Tamil Nadu is also home to the Tamil film industry nicknamed as Kollywood and is one of the largest industries of film production in India.[189][190] The term Kollywood is a blend of Kodambakkam and Hollywood.[191] Samikannu Vincent, who had built the first cinema of South India in Coimbatore, introduced the concept of "Tent Cinema" in the early 1900s, in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land close to a town or village to screen the films. The first of its kind was established in Madras, called "Edison's Grand Cinemamegaphone".[192][193][194] The first silent film in South India was produced in Tamil in 1916 and the first Tamil talkie film was Kalidas, which released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after the release of India's first talking picture Alam Ara.[195][196]

Clothing

[edit]

Ancient literature and epigraphical records describe the various types of dresses.[197][198] Tamil women traditionally wear a sari, a garment that consists of a drape varying from 4.6 m (15 ft) to 8.2 m (27 ft) in length and 0.61 m (2 ft) to 1.2 m (4 ft) in breadth that is typically wrapped around the waist, with one end draped over the shoulder, baring the midriff.[199][200][201] Women wear colourful silk sarees on traditional occasions.[202][203] Young girls wear a long skirt called pavaadai along with a shorter length sari called dhavani.[198] Kanchipuram silk sari is a type of silk sari made in the Kanchipuram region in Tamil Nadu and these saris are worn as bridal & special occasion saris by most women in South India. It has been recognized as a Geographical indication by the Government of India in 2005–2006.[204][205] Kovai Cora cotton is a specific type of cotton saree made in the Coimbatore region.[205][206]

The men wear a dhoti, a 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) long, white rectangular piece of non-stitched cloth often bordered in brightly coloured stripes which is usually wrapped around the waist and the legs and knotted at the waist.[198][201][207] A colourful lungi with typical batik patterns is the most common form of male attire in the countryside.[198][208] People in urban areas generally wear tailored clothing, and western dress is popular. Western-style school uniforms are worn by both boys and girls in schools, even in rural areas.[208]

Calendar

[edit]The Tamil calendar is a sidereal solar calendar.[209] The Tamil Panchangam is based on the same and is generally used in contemporary times to check auspicious times for cultural and religious events.[210] The calendar follows a 60-year cycle.[211] There are 12 months in a year starting with Chithirai when the Sun enters the first Rāśi and the number of days in a month varies between 29 and 32.[212] The new year starts following the March equinox in the middle of April.[213] The days of week (kiḻamai) in the Tamil calendar relate to the celestial bodies in the solar system: Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn, in that order.[214]

Food and hospitality

[edit]

Hospitality is a major feature of Tamil culture.[215] It was considered as a social obligation and offering food to guests was regarded as one of the highest virtues.[216][217] Rice is the diet staple and is served with sambar, rasam, and poriyal as a part of a Tamil meal.[218][219] Bananas find mention in the Sangam literature and the traditional way of eating a meal involves having the food served on a banana leaf, which is discarded after the meal. Eating on banana leaves imparts a unique flavor to the food, and is considered healthy.[220][221][222] Food is usually eaten seated on the floor and the finger tips of the right hand is used to take the food to the mouth.[223]

There are regional sub-varieties namely Chettinadu, Kongunadu, Nanjilnadu, Pandiyanadu and Sri Lankan Tamil cuisines.[224][225] There are both vegetarian and meat dishes with fish traditionally consumed across the coast and other meat preferred in the interiors. The Chettinadu cuisine is popular for its meat based dishes and generous usage of spices.[226] The Kongunadu cuisine uses less spices and are generally cooked fresh. It uses coconut, sesame seeds, groundnut, and turmeric to go with various cereals and pulses grown in the region.[226][227] Nanjilnadu cuisine is milder and is usually based on fish and vegetables.[226] Sri Lankan Tamil cuisine uses gingelly oil and jaggery along with coconut and spices, which differentiates it from the other culinary traditions in the island.[225] Biryani is a popular dish with several different versions prepared across various regions.[227] Idli, and dosa are popular breakfast dishes and other dishes cooked by to the Tamil people include upma,[228] idiappam,[229] pongal,[230] paniyaram,[231] and parotta.[232]

Medicine

[edit]Siddha medicine is a form of traditional medicine originating from the Tamils and is one of the oldest systems of medicine in India.[233] The word literally means perfection in Tamil and the system focuses on wholesome treatment based on various factors. As per Tamil tradition, the knowledge of Siddha medicine came from Shiva, which was passed on to 18 holy men known as Siddhar led by Agastya. The knowledge was then passed on orally and through palm leaf manuscripts to the later generations.[234] Siddha practitioners believe that all objects including the human body is composed of five basic elements – earth, water, fire, air, sky which are present in food and other compounds, which is used as the basis for the drugs and other therapies.[235]

Festivals

[edit]

Pongal is a major and multi-day harvest festival celebrated by Tamils in the month of Thai according to the Tamil solar calendar (usually falls on 14 or 15 January).[236][237] It is dedicated to the Surya, the Sun God and the festival is named after the ceremonial "Pongal", which means "to boil, overflow" and refers to the traditional dish prepared from the new harvest of rice boiled in milk with jaggery offered to Surya.[238][239][240][241] Mattu Pongal is meant for celebration of cattle when the cattle are bathed, their horns polished and painted in bright colors, garlands of flowers placed around their necks and processions.[242][243] Jallikattu is a traditional event held during the period attracting huge crowds in which a bull is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull's back with both arms and hang on to it while the bull attempts to escape.[244][245]

Puthandu is known as Tamil New Year which marks the first day of year on the Tamil calendar and falls on in April every year on the Gregorian calendar.[247] Karthikai Deepam is a festival of lights that is observed on the full moon day of the Kartika month, called the Kartika Pournami, falling on the months of November or December.[248][249] Thaipusam is a Tamil festival celebrated on the first full moon day of the Tamil month of Thai coinciding with Pusam star and dedicated to Murugan.[250][251] Aadi Perukku is a Tamil cultural festival celebrated on the 18th day of the Tamil month of Adi which pays tribute to water's life-sustaining properties. The worship of Amman and Ayyanar deities are organized during the month in temples across Tamil Nadu with much fanfare.[132] Panguni Uthiram is marked on the purnima (full moon) of the month of Panguni and celebrates the wedding of various Hindu gods.[252][253] Vaikasi Visakam is celebrated on the day the moon transits the Visaka nakshatram in Vaikasi (May–June), the second month of the Tamil Calendar and commemorates the birth of Murugan.[254][255] Eid al-Fitr is the major Muslim festival celebrated by the Tamils.[256] Other festivals celebrated include Ganesh Chaturthi, Navarathri, Deepavali and Christmas.[257][258][259]

Religion

[edit]As per the Sangam era works, the Sangam landscape was classified into five categories known as thinais, which were associated with a Hindu deity: Murugan in kurinji (hills), Thirumal in mullai (forests), Indiran in marutham (plains), Varunan in the neithal (coasts) and Kotravai in palai (desert).[260] Thirumal is indicated as a deity during the Sangam era, who was regarded as Paramporul ("the suprement one") and is also known as Māyavan, Māmiyon, Netiyōn, and Māl in various Sangam literature.[261][262] While Shiva worship existed in the Shaivite culture as a part of the Tamil pantheon, Murugan became regarded as the Tamil kadavul ("God of the Tamils").[263][264][265] There are a number of hill temples dedicated to Murugan foremost of which are the group of six Arupadaiveedu temples.[266] As per the Hindu epic Ramayana (7th to 5th century BCE), Rama crossed over to Sri Lanka from the Rameswaram island via the Rama Setu on his journey to rescue his wife, Sita from the Ravana.[267][268]

Jainism existed from the Sangam era with inscriptions and drip-ledges from 1st century BCE to 6th century CE and temple monuments likely built by Digambara Jains in the 9th century CE found in Chitharal and several Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, stone beds and sculptures from more than 2,200 years ago found in Samanar hills.[269][270] The Kalabhra dynasty, who were patrons of Jainism, ruled over the ancient Tamil country in the 3rd–7th century CE.[271][272] Old Jain temples include Kanchi Trilokyanatha temple, Chitharal Jain Temple, and the Tirumalai temple complex that houses a 16 ft (4.9 m) high sculpture of Neminatha dated from the 12th century CE.[273][274][275] Buddhism had an influence in Tamil Nadu before the later Middle Ages with ancient texts referring to a Vihāra in Nākappaṭṭinam from the time of Ashoka in 3rd century BCE and Buddhist relics from 4th century CE found in Kaveripattinam.[276][277] The Chudamani Vihara in Nagapattinam was later re-built by the Srivijaya king Maravijayottunggavarman under the patronage of Raja Raja Chola I in early 11th century CE.[278] Around the 7th century CE, the Pandyas and Pallavas, who patronized Buddhism and Jainism, became patrons of Hinduism following the revival of Saivism and Vaishnavism during the Bhakti movement led by Alwars and Nayanmars.[279][53] The Bhakti movement gave rise to the 108 Divya Desams dedicated to Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, that are mentioned in the works of the Alvars,[280] and the various Shaivite temples dedicated to Shiva including the 276 Paadal Petra Sthalams that are revered in the verses of Nayanars in the 6th-9th century CE and Pancha Bhuta Sthalams each representing a manifestation of the five prime elements of nature.[281][282]

In Tamil tradition, Murugan is the youngest son of Shiva and Parvati and Pillayar is regarded as the eldest son, who is venerated as the Mudanmudar kadavul ("foremost god").[283] The worship of Amman, also called Mariamman, is thought to have been derived from an ancient mother goddess, and is also very common.[284][285][286] In rural areas, local deities, called Aiyyan̲ār (also known as Karuppan, Karrupasami), are worshipped who are thought to protect the villages from harm.[284][287] Idol worship forms a part of the Tamil Hindu culture similar to the Hindu traditions.[288][289] Large idols are common with Namakkal Anjaneyar Temple hosts a 18 ft (5.5 m) tall Hanuman statue and temples like the Eachanari Vinayagar temple in Coimbatore, Karpaka Vinayakar temple in Pillayarapatti, and Uchippillaiyar temple in Tiruchirappalli accommodating large Ganesha statues.[290][291][292]

The Christian apostle, St. Thomas, is believed to have preached Christianity in the area around Chennai between 52 and 70 CE and the Santhome Church, which was originally built by the Portuguese in 1523, is believed to house the remains of St. Thomas, was rebuilt in 1893 in neo-Gothic style.[293] The 16th century CE Basilica of Our Lady of Good Health at Velankanni, known as the 'Lourdes of the East', was declared as a holy city by the pope and is the primary place of worship of Tamil Christians.[294] Islam was introduced due to the influence of the Arab merchants and the Muslim rulers from the north in the middle ages. The majority of Tamil Muslims speak Tamil rather than Urdu as their mother tongue as they were converts from the native population.[295][296] Erwadi in Ramanathapuram district, which houses an 840-year-old mosque and Nagore Dargah are important places of worship for Tamil Muslims.[297][298]

As of the 21st century, majority of the Tamils are adherents of Hinduism.[299] The migration of Tamils to other countries resulted in new Hindu temples being constructed in places with significant population of Tamil people and people of Tamil origin, and countries with significant Indian migrants.[300] Sri Lankan Tamils predominantly worship Murugan with numerous temples existing throughout the island including Kataragama temple, Nallur Kandaswamy temple and Maviddapuram Kandaswamy Temple.[301][302] Amongst the other notable temples is the Sri Subramanyar Temple at Batu Caves temple complex in Malaysia, which has one of the largest Murugan statues in the world.[303][304] Atheist, rationalist, and humanist philosophies are also adhered by sizeable minorities, as a result of Tamil cultural revivalism in the 20th century, and its antipathy to what it saw as Brahminical Hinduism.[305]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Archaeology – Anthropology : Sharp stones found in India signal surprisingly early toolmaking advances". 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Very old, very sophisticated tools found in India. The question is: Who made them?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution". The Times of India. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ Shekar, Anjana (21 August 2020). "Keezhadi sixth phase: What do the findings so far tell us?". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Vijaya Ramaswamy; Jawaharlal Nehru (25 August 2017). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxiv. ISBN 978-1-53810-686-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Francis, Emmanuel (28 October 2021). "Pallavas". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1002/9781119399919.eahaa00499. ISBN 978-1-119-39991-9. S2CID 240189630. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ J.B.P. More (2020). Pondicherry, Tamil Nadu and South India Under French Rule: From François Martin to Dupleix 1674-1754. Manohar. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-00026-356-5. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "The Edicts of King Ashoka". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni

- ^ "On the Roman Trail". The Hindu. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ Susan Wadley (2014). South Asia in the World: An Introduction. Taylor and Francis. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-31745-958-3. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ John Man (1999). Atlas of the year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-674-54187-0.

- ^ "Chola dynasty". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "India's independence". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Christophe Z. Guilmoto (January 1993). "The Tamil Migration Cycle, 1830-1950". Economic and Political Weekly. 28 (3/4): 111–120. JSTOR 4399307.

- ^ Wagret, Paul (1977). Nagel's encyclopedia-guide. Geneva: Nagel Publishers. p. 556. ISBN 978-2-82630-023-6. OCLC 4202160.

- ^ a b "Tamil Diaspora". Institute of Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Irregular migration". United Nations. May 2010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Kelsey Clark Underwood. "Image and Identity: Tamil Migration to the United States" (PDF). University of California. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Tamils". Minority rights group. 16 October 2023. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Anthony Goreau-Ponceaud. India and Tamil nationalism (Report). Les Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge University Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-52177-111-5.

- ^ Tamil among the classical languages of the world (PDF) (Report). Tamil Virtual University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Tamil language". Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Iravatham Mahadevan. Early Tamil Epigraphy From The Earliest Times To The Sixth Century A. D. harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67401-227-1.

- ^ "A rare inscription". The Hindu. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay (3 August 2021). "Ancestral Dravidian languages in Indus Civilization". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00868-w. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ R.E.Asher; E.Annamalai (2002). Colloquial Tamil (PDF). Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-41518-788-6.

- ^ Southworth, Franklin C. (2005). Linguistic archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. pp. 129–132. ISBN 978-0-41533-323-8.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (2010). Pre-history of Tamil literature (PDF) (Report). p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Five fold grammar of Tamil". University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ P.M.Gangatharan. "Puraporul Ilakkanam- General Introduction". Tamil Virtual University. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Ramasamy, Sumathi (1997). "Feminizing Language: Tamil as Goddess, Mother, Maiden". Passions of the Tongue: Language Devotion in Tamil India, 1891-1970. Vol. 29. University of California. pp. 79–134. ISBN 978-0-520-20804-9. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Smirnitskaya, Anna (March 2019). "Diglossia and Tamil varieties in Chennai". Acta Linguistica Petropolitana (3): 318–334. doi:10.30842/alp2306573714317. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Several dialects of Tamil". The Hindu. 31 October 2023. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b George L. Hart (August 2018). Credentials of Tamil as a classical language (PDF) (Report). Tamil Virtual University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Maloney, C. (1970). "The Beginnings of Civilization in South India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 29 (3): 603–616. doi:10.2307/2943246. JSTOR 2943246. S2CID 162291987.

- ^ Subramaniam, T.S. (29 August 2011). "Palani excavation triggers fresh debate". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Abraham, S. A. (2003). "Chera, Chola, Pandya: Using Archaeological Evidence to Identify the Tamil Kingdoms of Early Historic South India" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 42 (2): 207. doi:10.1353/asi.2003.0031. hdl:10125/17189. S2CID 153420843. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Nadarajah, Devapoopathy (1994). Love in Sanskrit and Tamil Literature: A Study of Characters and Nature, 200 B.C.-A.D. 500. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 978-8-12081-215-4.

- ^ Diego Marin; Ivan Minella; Erik Schievenin (2013). The Three Ages of Atlantis: The Great Floods That Destroyed Civilization. Inner Traditions/Bear. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-59143-757-4. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b Zvelebil, Kamil (1992). Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. Brill Publishers. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-9-00409-365-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ M. S. Purnalingam Pillai (1994). Tamil Literature. Asian Educational Services. p. 2. ISBN 978-8-12060-955-6. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Mahajan V.D. Ancient India. S. Chand Publishing. p. 610. ISBN 978-9-35253-132-5. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Overview of Sangam literature". Tamil Sangam. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ The Ancient Tamils as depicted in Tolkāppiyam (PDF). S.K.Pillai. 1934. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Shulman, David (2016). Tamil. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67497-465-4. Archived from the original on 14 July 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Takahashi, Takanobu (1995). Tamil Love Poetry and Poetics. Brill Publishers. pp. 1–3. ISBN 90-04-10042-3. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b Early Tamil society (PDF) (Report). Indira Gandhi National Open University. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ T.V. Mahalingam (1981). Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference of the South Indian History Congress. University of Michigan. pp. 28–34.

- ^ S. Sundararajan (1991). Ancient Tamil Country: Its Social and Economic Structure. Navrang. p. 233.

- ^ P.S.Sundaram (2005). The Kural. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-9-35118-015-9. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ a b Pillai, P. Govinda (4 October 2022). The Bhakti Movement: Renaissance or Revivalism?. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-00078-039-0. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Padmaja, T. (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamil nāḍu. Abhinav Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-8-17017-398-4. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Nair, Rukmini Bhaya; de Souza, Peter Ronald (2020). Keywords for India: A Conceptual Lexicon for the 21st Century. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-35003-925-4.

- ^ P.S.Sundaram (3 May 2002). Kamba Ramayana. Penguin Books. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-9-351-18100-2. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Bergunder, Michael; Frese, Heiko; Schröder, Ulrike (2011). Ritual, Caste, and Religion in Colonial South India. Primus Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-9-380-60721-4. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Karthik Madhavan (21 June 2010). "Tamil saw its first book in 1578". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 June 2014). "Delay, howlers in Tamil Lexicon embarrass scholars". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ "The Tamil Lexicon". The Hindu. 27 March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Karen Prechilis (1999). The embodiment of bhakti. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19512-813-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Arooran, K. Nambi (1980). Tamil Renaissance and the Dravidian Movement, 1905-1944. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Theodore Baskaran (19 March 2014). "Seeds of Tamil Renaissance". Frontline. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Bharathiyar Who Impressed Bharatidasan". Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies. ISSN 1305-578X. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Indian Literature: An Introduction. Pearson Education. 2005. p. 125. ISBN 978-8-13170-520-9. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Centur̲aimuttu (1978). Āya kalaikaḷ ar̲upattunān̲ku. University of Michigan. p. 2. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Cuppiramaṇiyan̲, Ca. Vē (1983). Heritage of the Tamils: Siddha Medicine. International Institute of Tamil Studies. p. 554.

- ^ Jose Joseph; L. Stanislaus, eds. (2007). Communication as Mission. Indian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 123. ISBN 978-8-18458-006-8. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ Fergusson, James (1910). History of Indian and Eastern Architecture: Volume 1. London: John Murray. p. 309.

- ^ a b Francis Ching (1995). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture (PDF). New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-4712-8451-2.

- ^ Francis Ching; Mark M. Jarzombek; Vikramaditya Prakash (2017). A Global History of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-11898-161-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ David Rose (1995). Hinduism. Folens. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-85276-770-9. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Jeannie Ireland (2018). History of Interior Design. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-50131-989-1. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Susan L. Huntington; John C. Huntington (2014). The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 313. ISBN 978-8-12083-617-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Dayalan, D. (2014). Cave-temples in the Regions of the Pāṇdya, Muttaraiya, Atiyamān̤ and Āy Dynasties in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ K. R. Srinivasan (1964). Cave-temples of the Pallavas. Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. Rosen Publishing. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-82393-179-8.

- ^ Sacred Places of a Lifetime: 500 of the World's Most Peaceful and Powerful Destinations. National Geographic Society. 2008. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-42620-336-7.

- ^ Om Prakash (2005). Cultural History of India. New Age International. p. 15. ISBN 978-8-12241-5-872. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Crispin Branfoot (2015). "The Tamil Gopura From Temple Gateway to Global Icon". Ars Orientalis. 45 (20220203). University of Michigan. doi:10.3998/ars.13441566.0045.004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Michell, George (1988). The Hindu Temple. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-0-22653-230-1.

- ^ "Gopuram". Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ "Kanchipuram". Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Meenakshi Amman Temple". Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "A tower that is emblematic of the State". The Hindu. 14 April 2022. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Which Tamil Nadu temple is the state emblem?". Times of India. 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ S.R. Balasubrahmanyam (1975). Middle Chola Temples. Thomson Press. pp. 16–29. ISBN 978-9-0602-3607-9.

- ^ Neela, N.; Ambrosia, G. (April 2016). "Vimana architecture under the Cholas" (PDF). Shanlax International Journal of Arts, Science & Humanities. 3 (4): 57. ISSN 2321-788X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Arjun Senguptha (21 January 2024). "What is the Nagara style, in which Ayodhya's Ram temple is being built". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh build temple ties to boost tourism". The Times of India. 10 August 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Ten Hindu temples to visit outside India". The Economic Times. 23 October 2021. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Five Hindu temples to visit outside India that are worth a visit". The Times of India. 29 October 2021. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Metcalfe, Thomas R. "A Tradition Created: Indo-Saracenic Architecture under the Raj". History Today. 32 (9). Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Indo-saracenic Architecture". Henry Irwin, Architect in India, 1841–1922. higman.de. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Jeyaraj, George J. Indo Saracenic Architecture in Channai (PDF) (Report). Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "Art Deco Style Remains, But Elements Missing". The New Indian Express. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Chennai, a rich amalgamation of various architectural styles". The Hindu. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 17 July 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Chennai looks to the skies". The Hindu. 31 October 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Krishna Rajamannar with His Wives, Rukmini and Satyabhama, and His Mount, Garuda | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Ganapathi, V. "Shilpaic literature of the tamils". INTAMM. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2006.

- ^ Lippe, Aschwin (December 1971). "Divine Images in Stone and Bronze: South India, Chola Dynasty (c. 850–1280)". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 4. The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 29–79. doi:10.2307/1512615. JSTOR 1512615. S2CID 192943206.

The bronze icons of the Early Chola period are one of India's greatest contributions to world art...

- ^ Vidya Dehejia (1990). Art of the Imperial Cholas. Columbia University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-23151-524-5. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Ē. En̲ Perumāḷ (1983). Ca. Vē Cuppiramaṇiyan̲ (ed.). Heritage of the Tamils: Art & Architecture. International Institute of Tamil Studies. p. 459. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Sudharsanam. A centre for Arts and Culture (PDF). Indian Heritage Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ "Sittanavasal – A passage to the Indian History and Monuments". Puratattva. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ "The Ajanta of TamilNadu". The Tribune. 27 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ K. Rajayyan (2005). Tamil Nadu, a Real History. University of Michigan. p. 188. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Raghavan Srinivasan. Rajaraja Chola: Interplay Between an Imperial Regime and Productive Forces of Society. Leadstart Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-9-35458-2-233. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Nayanthara, S. (2006). The World of Indian murals and paintings. Chillbreeze. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-8-19040-551-5. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ C. B. Gupta; Mrinalini Mani (2005). Thanjavur Paintings: Materials, Techniques & Conservation. National Museum. p. 14. ISBN 978-8-18583-223-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Appasamy, Jaya (1980). Tanjavur Painting of the Maratha Period: Volume 1. Abhinav Publications. p. 9. ISBN 978-8-17017-127-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Rajagopal, Geetha (2009). Music rituals in the temples of South India, Volume 1. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-8-12460-538-7.

- ^ Nijenhuis, Emmie te (1974). Indian Music: History and Structure. Brill Publishers. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-9-00403-978-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Tamil Pozhil (in Tamil). Karanthai Tamil Sangam. 1976. p. 241. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Richard Widdess (December 2019). "Orality, writing and music in South Asia". School of Oriental and African Studies. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.31623.96169.

- ^ Widdess, D. R. (1979). "The Kudumiyamalai inscription: a source of early Indian music in notation". In Picken, Laurence (ed.). Musica Asiatica. Vol. 2. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 115–150.

- ^ T. K. Venkatasubramanian (2010). Music as a history in Tamil Nadu. Primus Books. p. ix-xvi. ISBN 978-9-38060-7-061. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Karnatak music". Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Alastair Dick (1984). Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 3. Macmillan Press. p. 727. ISBN 978-0-943818-05-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 1988. p. 1314. ISBN 978-8-12601-194-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ G, Ezekiel Majello (10 October 2019). "Torching prejudice through gumption and Gaana". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Jeff Todd Titon; Svanibor Pettan, eds. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Applied Ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-199-35171-8.

- ^ Ramkumar, Nithyau (2016). Harihara the Legacy of the Scroll. Frog in well. ISBN 978-9-352-01769-0.

..Thaarai and thappattai, native instruments of Tamil people..

- ^ S.Krishnaswami (2017). Musical Instruments of India. Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India. ISBN 978-8-12302-494-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Secular and sacred". The Hindu. 3 January 2013. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Kiruṣṇan̲, Rājam (2002). When the Kurinji Blooms. Orient BlackSwan. p. 124. ISBN 978-8-12501-619-9.

- ^ K.Leelavathy. Problems and prospects of handicraft artisans in thanjavur district. Archers & Elevators Publishing House. pp. 38, 43. ISBN 978-8-11965-350-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Mathalam - Ancient music instruments mentioned in Thirumurai" (in Tamil). Shaivam.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013.

- ^ "11th TirumuRai Paurams" (in Tamil). Project Madurai. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b "An ode to Aadi and Ayyanar". Indian Express. 26 July 2022. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Pillai, S. Subramania (2019). Tourism in Tamil Nadu: Growth and Development. MJP Publisher. p. 14. ISBN 978-8-18094-432-1. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Margazhi season". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Chennai music season begins with 'Chennaiyil Thiruvaiyaru' festival". Indian Express. 5 December 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Knight, Douglas M. Jr. (2010). Balasaraswati: Her Art and Life. Wesleyan University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8195-6906-6. Archived from the original on 14 July 2024. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ a b Lochtefeld, James (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M (PDF). Rosen Publishing. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-82393-179-8.

- ^ "Bhartanatyam". Government of India. Archived from the original on 30 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Banerjee, Projesh (1983). Indian Ballet Dancing. Abhinav Publications. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-391-02716-9. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Bharata-natyam". Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "On International Dance Day, a look at some of India's famous dance forms and their exponents". The Indian Express. 29 April 2023. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Richard Schechner (2010). Between Theater and Anthropology. University of Pennsylvania. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-81227-929-0.

- ^ Performing Arts: Detailed study of Bharatanatyam (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Gurcharan Singh Randhawa; Amitabha Mukhopadhyay (1986). Floriculture in India. Allied Publishers. pp. 607–608. ISBN 978-8-17023-494-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Swarajya Prakash Gupta; Krishna Lal; Mahua Bhattacharyya (2002). Cultural tourism in India: museums, monuments & arts. Indraprastha Museum of Art and Archaeology. p. 198. ISBN 978-8-12460-215-7.

- ^ Janet O'Shea (2007). At Home in the World: Bharata Natyam on the Global Stage. Wesleyan University. pp. 70, 162, 198–200. ISBN 978-0-81956-837-3.

- ^ Hanne M. de Bruin (1999). Kaṭṭaikkūttu: The Flexibility of a South Indian Theatre Tradition. University of Michigan. p. 344. ISBN 978-9-06980-103-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Heesterman, J. C. (1992). Ritual, State, and History in South Asia. Brill Publishers. p. 465. ISBN 978-9-00409-467-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Ethical Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. 2010. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-25335-528-7. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Kent, Alexandra (2005). Divinity and Diversity: A Hindu Revitalization Movement in Malaysia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 170–174. ISBN 978-8-79111-489-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Hume, Lynne (2020). Portals: Opening Doorways to Other Realities Through the Senses. Taylor & Francis. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-00018-987-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Shobana Gupta (2010). Dances Of India. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 60–65. ISBN 978-8-12411-337-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Govindarajan, Aburva (2016). Footprints of a Young Dancer:Journey & Experience. eBooks2go. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-61813-360-1. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Kolattam". Merriam Webster. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil Culture in Ceylon: A General Introduction. University of Michigan. pp. 274–275. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Allison Arnold, ed. (2017). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Taylor & Francis. p. 990. ISBN 978-1-35154-438-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Madhavan, Arya (2010). Kudiyattam Theatre and the Actor's Consciousness. Brill Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 978-9-04202-799-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Gaurab Dasgupta (2024). Jhal Muri: Embracing Life's Unpredictable Flavours. Blue Rose. p. 207. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Soneji, Devesh; Viswanathan Peterson, Indira (2008). Reinventing the Arts in Modern South India. Oxford University Press. pp. 334–335. ISBN 978-0-19569-084-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Folk dances". Seminar: The Monthly Symposium. Romeshraj Trust: 35. 1993.

- ^ "Oyilattam". Government of Tamil Nadu, South Zone Cultural Center. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ Shah, Niraalee (2021). Indian Etiquette:A Glimpse Into India's Culture. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-63886-554-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Folk dances of South India". Cultural India. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Parai". Nathalaya. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Ramkumar, Nithyau (2016). Harihara the Legacy of the Scroll. Frog in well. ISBN 978-9-35201-769-0.

..Thaarai and thappattai, native instruments of Tamil people..

- ^ Spirit of the Tiger. Parragon Publishing. 2012. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-44545-472-6. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2016). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-44225-749-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ History, Religion and Culture of India. Isha books. 2004. p. 224. ISBN 978-8-18205-061-7. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Vatsyayan, Kapila (1987). Traditions of Indian Folk Dance. Clarion Books. p. 337. ISBN 978-8-18512-022-5. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Narayan, M.K.V. (2007). Flipside of Hindu Symbolism:Sociological and Scientific Linkages in Hinduism. Fultus Corporation. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-1-59682-117-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Shovana Narayan (2004). Folk Dance Traditions of India. Shubhi Publication. pp. 226–227. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Axel Michaels; Christoph Wulf, eds. (2012). Images of the Body in India: South Asian and European Perspectives on Rituals and Performativity. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-13670-392-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Wolf, Gita; Geetha, V.; Ravishankar, Anushka (2003). Masks and Performance with Everyday Materials. Tara Publishing. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-8-18621-147-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Liu, Siyuan (2016). Routledge Handbook of Asian Theatre. Taylor & Francis. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-317-27886-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Lal, Ananda (2009). Theatres of India: A Concise Companion. Oxford University Press. pp. 71, 433. ISBN 978-0-19569-917-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Brandon, James; Banham, Martin (1997). The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

- ^ "Chennai Sangamam to return after a decade". The Times of India. 30 December 2022. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Martial Arts (Silambam & Kalaripayattu)". Government of India. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Nainar, Nahla (20 January 2017). "A stick in time …". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Sarkar, John (17 February 2008). "Dravidian martial art on a comeback mode". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b Chris Crudelli (2008). The Way of the Warrior. Dorling Kindersley. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-40533-750-2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Adimurai". The Hans India. 18 February 2023. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Luijendijk, D.H. (2005). Kalarippayat: India's Ancient Martial Art. Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-40922-626-0.

- ^ Zarrilli, Phillip B. (1992). "To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots (Marmmam/Varmam) in Two South Indian Martial Traditions Part I: Focus on Kerala's Kalarippayattu". Journal of Asian Martial Arts. 1 (1). Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Alter, Joseph S. (May 1992). "The sannyasi and the Indian wrestler: the anatomy of a relationship". American Ethnologist. 19 (2): 317–336. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.2.02a00070. ISSN 0094-0496. JSTOR 645039. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Silambam weapons". World Silambam Association. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Hidden Dance of the Deadly Staff". Daily News. 13 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 21, 386. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Tamil Nadu leads in film production". The Times of India. 22 August 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ Bureau, Our Regional (25 January 2006). "Tamil, Telugu film industries outshine Bollywood". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

{{cite news}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Hiro, Dilip (2010). After Empire: The Birth of a Multipolar World. PublicAffairs. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-56858-427-0. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "A way of life". Frontline. 18 October 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "Cinema and the city". The Hindu. 9 January 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ "Farewell to old cinema halls". Times of India. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Velayutham, Selvaraj (2008). Tamil cinema: the cultural politics of India's other film industry. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-39680-6. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "From silent films to the digital era — Madras' tryst with cinema". The Hindu. 30 August 2020. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Parthasarathy, R. (1993). The Tale of an Anklet: An Epic of South India – The Cilappatikaram of Ilanko Atikal, Translations from the Asian Classics. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-23107-849-8.

- ^ a b c d Vijaya Ramaswamy (2017). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-53810-686-0. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Boulanger, Chantal (1997). Saris: An Illustrated Guide to the Indian Art of Draping. New York: Shakti Press International. p. 6,15. ISBN 978-0-96614-961-6. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Lynton, Linda (1995). The Sari. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-50028-378-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ a b Anurag Kumar (2016). Indian Art & Culture. Arihant Publication. p. 196. ISBN 978-9-35094-484-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Nick Huyes (10 May 2024). Exploring The Riches Of India. Nicky Huys Books. p. 47. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ C. Monahan, Susanne; Andrew Mirola, William; O. Emerson, Michael (2001). Sociology of Religion. Prentice Hall. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-13025-380-4.

- ^ "Weaving through the threads". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ a b Geographical indications of India (PDF) (Report). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "31 ethnic Indian products given". Financial Express. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "About Dhoti". Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Clothing in India". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Robert Sewell; Sankara Dikshit (1995). The Indian Calendar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Singapore Ethnic Mosaic, The: Many Cultures, One People. World Scientific Publishing Company. 2017. p. 226. ISBN 978-9-81323-475-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Sixty year cycle" (PDF). Sankara Vedic Culture and Arts. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ S.K. Chatterjee (1998). Indian Calendric System. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. p. 809. ISBN 978-1-59339-491-2. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Johann Philipp Fabricius (1998). Tamil dictionary. Asian Educational Services. p. 631. ISBN 978-8-12060-264-9. Archived from the original on 6 August 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ A. Kiruṭṭin̲an̲ (2000). Tamil Culture: Religion, Culture, and Literature. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 77. ISBN 978-8-18605-052-1.

- ^ Selwyn Stanley (2004). Social Problems in India. Allied Publishers. p. 658. ISBN 978-8-17764-708-2. Archived from the original on 15 July 2024. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Hospitality Characteristics of Tamil People". International Tamil Research. 4. 2022. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ "Rediscovering the richness of rice". The New Indian Express. 9 July 2024. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ South India Heritage: An Introduction. East West Books. 2007. p. 412. ISBN 978-8-18866-164-0.

- ^ The Bloomsbury Handbook of Indian Cuisine. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2023. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-350-12864-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Serving on a banana leaf". ISCKON. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "The Benefits of Eating Food on Banana Leaves". India Times. 9 March 2015. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Kalman, Bobbie (2009). India: The Culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7787-9287-1. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Food recipes". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Big, bold flavours from a small island". Deccan Herald. 28 January 2024. Archived from the original on 28 January 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "India's pluralism: Traditional cuisines of Tamil Nadu largely about meat & fish". The Economic Times. 11 October 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Flavours of Kongunadu: There are several Tamil Nadus when it comes to food". The New Indian Express. 22 July 2023. Archived from the original on 22 July 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "6 Breakfast Items From Tamil Nadu To Have Instead Of Idli and Dosa". Times Now. 27 March 2024. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Achaya, K.T. (1 November 2003). The Story of Our Food. Universities Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-8-17371-293-7.

- ^ Conrad Bunk, ed. (2009). Acceptable Genes? Religious Traditions and Genetically Modified Foods. SUNY Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-43842-894-9. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ George Abraham Pottamkulam (2021). Tamilnadu A Journey in Time Part II People, Places and Potpourri. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-63806-520-3. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai (2020). India, Sri Lanka and the SAARC Region: History, Popular Culture and Heritage. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-00020-581-7. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "About Siddha medicine: Origins". National Institute of Siddha. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "About Siddha". Government of India. Retrieved 1 June 2024.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Siddha system of medicine (PDF) (Report). National Siddha Council. August 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ James Stewart (2015). Vegetarianism and Animal Ethics in Contemporary Buddhism. Taylor & Francis. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-31762-398-4. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Beteille, Andre (1964). "89. A Note on the Pongal Festival in a Tanjore Village". Man. 64. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 73–75. doi:10.2307/2797924. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2797924.

- ^ Denise Cush; Catherine A. Robinson; Michael York (2008). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Psychology Press. pp. 610–611. ISBN 978-0-7007-1267-0. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ R Abbas (2011). S Ganeshram and C Bhavani (ed.). History of People and Their Environs. Bharathi Puthakalayam. pp. 751–752. ISBN 978-9-38032-591-0. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 547–548. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ^ Roy W. Hamilton; Aurora Ammayao (2003). The art of rice: spirit and sustenance in Asia. University of California Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-93074-198-3. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ G. Eichinger Ferro-Luzzi (1978). "Food for the Gods in South India: An Exposition of Data". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. Bd. 103, H. 1 (1). Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH: 86–108. JSTOR 25841633.

- ^ Sandhya Jain (2022). Adi Deo Arya Devata: A Panoramic View oF Tribal-Hindu Cultural Interface. Notion Press. p. 182. ISBN 979-8-88530-378-1. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Ramakrishnan, T. (26 February 2017). "Governor clears ordinance on 'jallikattu'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 May 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Jallikattu bull festival". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Abbie Mercer (2007). Happy New Year. Rosen Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4042-3808-4.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-14341-421-6. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Spagnoli, Cathy; Samanna, Paramasivam (1999). Jasmine and Coconuts: South Indian Tales. Libraries Unlimited. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-56308-576-5. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Gajrani, S. (2004). History, Religion and Culture of India. Gyan Publishing House. p. 207. ISBN 978-8-18205-061-7. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 462–463. ISBN 978-1-85109-689-3.

- ^ Alexandra Kent (2005). Divinity and Diversity: A Hindu Revitalization Movement in Malaysia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-8-79111-489-2.

- ^ Pechilis, Karen (22 March 2013). Interpreting Devotion: The Poetry and Legacy of a Female Bhakti Saint of India. Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-136-50704-5. Archived from the original on 13 February 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Chambers, James (2015). Holiday Symbols & Customs. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-780-81365-6.

- ^ Subodh Kant (2002). Indian Encyclopedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 7821. ISBN 978-8-177-55257-7.

- ^ "Vaikasi Visakam: Date, Time, Significance". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "People offer mass prayers, exchange greetings in Tamil Nadu". Associated Press. 10 April 2024. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Important festivals of Tamilnadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. 14 June 2023. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Festivals". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 11 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Christmas in Tamil Nadu". Government of Tamil Nadu. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Chandramouli, C. (2004). Arts and Crafts of Tamil Nadu. Directorate of Census Operations. p. 74.

- ^ Hardy, Friedhelm (2015). Viraha Bhakti: The Early History of Krsna Devotion. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 156. ISBN 978-8-12083-816-1.

- ^ Padmaja, T. (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ^ Clothey, Fred W. (2019). The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God. With the Poem Prayers to Lord Murukan. Walter de Gruyter. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-11080-410-2.

- ^ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2006). A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery. Harappa. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ^ Steven Rosen; Graham M. Schweig (2006). Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing. p. 45.

- ^ Aiyar, P.V.Jagadisa (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 191–203. ISBN 978-0-4708-2958-5.

- ^ "Rameswaram". Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Goldman, Robert P. (1984). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, Vol. I, Bālakānda (PDF). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-8-120-83162-9.

- ^ Nagarajan, Saraswathy (17 November 2011). "On the southern tip of India, a village steeped in the past". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ Subramanian, T. S. (24 March 2012). "2,200-year-old Tamil-Brahmi inscription found on Samanamalai". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2007). A History of India (4th ed.). London: Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-6700-8478-4. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Jain, Mahima A. (February 2016). "Looking for Jina Kanchi". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ "Chitharal". Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Arihantagiri – Tirumalai". Jain Heritage centres. 28 November 2011. Archived from the original on 31 January 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Rao, S.R. (1991). "Marine archaeological explorations of Tranquebar-Poompuhar region on Tamil Nadu coast" (PDF). Journal of Marine Archaeology. 2: 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Duraiswamy, Dayalan. Role of Archaeology on Maritime Buddhism. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.