-

Bajra is the main kharif crop in Thar.

-

Mustard fields in a village of Shri Ganganagar district (Rajasthan, India).

Thar Desert

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

| Thar Desert Great Indian Desert | |

|---|---|

Thar Desert in Rajasthan, India | |

Map of the Thar Desert ecoregion | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Indomalayan |

| Biome | Deserts and xeric shrublands |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 238,254 km2 (91,990 sq mi) |

| Countries | |

| States of India and provinces of Pakistan | |

| Coordinates | 27°N 71°E / 27°N 71°E |

| Climate type | Hot |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | vulnerable[1] |

| Protected | 41,833 km2 (18%)[2] |

The Thar Desert (Hindi pronunciation: [t̪ʰaːɾ]), also known as the Great Indian Desert, is an arid region in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent that covers an area of 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi) in India and Pakistan. It is the world's 18th-largest desert, and the world's 9th-largest hot subtropical desert.

About 85% of the Thar Desert is in India, and about 15% is in Pakistan.[3] The Thar Desert is about 4.56% of the total geographical area of India. More than 60% of the desert lies in the Indian state of Rajasthan; the portion in India also extends into Gujarat, Punjab, and Haryana. The portion in Pakistan extends into the provinces of Sindh[4] and Punjab (the portion in the latter province is referred to as the Cholistan Desert). The Indo-Gangetic Plain lies to the north, west and northeast of the Thar desert, the Rann of Kutch lies to its south, and the Aravali Range borders the desert to the east.

The most recent paleontological discovery in 2023 from the Thar Desert in India, dating back to 167 million years ago, pertains to a herbivorous dinosaur group known as dicraeosaurids. This discovery marks the first of its kind to be unearthed in India and is also the oldest specimen of the group ever recorded in the global fossil record.[5]

Geography

[edit]

The northeastern part of the Thar Desert lies between the Aravalli Hills. The desert stretches to Punjab and Haryana in the north, to the Great Rann of Kutch along the coast, and to the alluvial plains of the Indus River in the west and northwest. Much of the desert area is covered by huge, shifting sand dunes that receive sediments from the alluvial plains and the coast. The sand is highly mobile due to the strong winds that rise each year before the onset of the monsoon. The Luni River is the only river in the desert.[6] Rainfall is 100 to 500 mm (4 to 20 in) per year, almost all of it between June and September.[3]

Saltwater lakes within the Thar Desert include the Sambhar, Kuchaman, Didwana, Pachpadra, and Phalodi in Rajasthan and Kharaghoda in Gujarat. These lakes receive and collect rainwater during monsoon and evaporate during the dry season. The salt comes from the weathering of rocks in the region.[7]

Lithic tools belonging to the prehistoric Aterian culture of the Maghreb have been discovered in Middle Paleolithic deposits in the Thar Desert.[8]

Climate

[edit]The climate is arid and subtropical. Average temperature varies with season, and extremes can range from near-freezing in the winter to more than 50 °C in the summer months. Average annual rainfall ranges from 100 to 500 mm, and occurs during the short July-to-September southwest monsoon.[1]

The desert has both a very dry part (the Marusthali region in the west) and a semidesert part (in the east) that has fewer sand dunes and slightly more precipitation.[9]

Desertification

[edit]During the Last Glacial Maximum, approximately 20,000 years before present, an estimated 2,400,000 square kilometres (930,000 sq mi) ice sheet covered the Tibetan Plateau,[10][11][12] significantly affecting radiative forcing; due to its low latitude, the Tibetan ice sheet reflected at least four times more solar radiation per unit area into space than ice at higher latitudes, further cooling the overlying atmosphere during that period.[13] Without the thermal low pressure caused by the heating, there was no monsoon over the Indian subcontinent. This lack of monsoon caused extensive rainfall over the Sahara, expansion of the Thar Desert, more dust deposited into the Arabian Sea, a lowering of the biotic life zones on the Indian subcontinent, and animals responded to this shift in climate with the Javan rusa deer migrating into India.[14]

1 = ancient river

2 = today's river

3 = today's Thar desert

4 = ancient shore

5 = today's shore

6 = today's town

7 = dried-up Harappan Hakkra course, and pre-Harappan Sutlej paleochannels (Clift et al. (2012)).

Between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, a paleo channel of the Ghaggar-Hakra River – identified with the paleo Sarasvati River – after its confluence with the Sutlej flowed into the Nara river, a delta channel of the Indus River, but then changed its course. This left the Ghaggar-Hakra as a system of monsoon-fed rivers that no longer reached the sea and now ends in the Thar desert.[15][16][17][18]

Around 5,000 years ago, when the monsoons that fed the rivers diminished further, the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) prospered in this area,[15][17][18][b] with the rise of numerous IVC urban sites at Kalibangan (Rajasthan), Banawali and Rakhigarhi (Haryana), Dholavira and Lothal (Gujarat) along this course.[19][web 1]

By 4,000 years ago, when monsoons diminished even further, the dried-up Hakra became an intermittent river, and the urban Harappan civilisation declined, becoming localized in smaller agricultural communities.[15][c][17][16][18]

Desertification control

[edit]

The soil of the Thar Desert remains dry for much of the year, so it is prone to wind erosion. High-velocity winds blow soil from the desert, depositing some of it on neighboring fertile lands, and causing sand dunes within the desert to shift. To counteract this problem, sand dunes are stabilised by first erecting micro windbreak barriers with scrub material and then by afforestation of the treated dunes—planting the seedlings of shrubs (such as phog, senna, and castor oil plant) and trees (such as gum acacia, Prosopis juliflora, and lebbek tree). The 649-km-long Indira Gandhi Canal brings fresh water to the Thar Desert.[3] It was built to halt any spreading of the desert into fertile areas.

Protected areas

[edit]There are several protected areas in the Thar Desert:

- In India:

- The Desert National Park, in Rajasthan, covers 3,162 km2 (1,221 sq mi) and represents the Thar Desert ecosystem;[20] it includes 44 villages.[21] Its diverse fauna includes the great Indian bustard (Chirotis nigricaps), blackbuck, chinkara, fox, Bengal fox, wolf, and caracal. Seashells and massive fossilized tree trunks in Akal Wood Fossil Park record the geological history of the desert.

- The Tal Chhapar Sanctuary covers 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi) and is an Important Bird Area.[21] It is located in the Churu district, 210 km (130 mi) from Jaipur, in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan. This sanctuary is home to large populations of blackbuck, fox, caracal, partridge, and sand grouse.

- The Sundha Mata Conservation Reserve covers 117.49 km2 (45.36 sq mi) and is located in the Jalore District of Rajasthan.[22]

- In Pakistan:

- The Nara Desert Wildlife Sanctuary covers 6,300 km2 (2,400 sq mi);[23] it is located in is located in Mirpurkhas District.[24] It contains the largest population of the endangered mugger crocodile in Pakistan.[24]

- The Rann of Kutch Wildlife Sanctuary located in Badin District is an Important Bird Area and Ramsar Site, with 30 species of mammals, 112 bird species, 20 reptiles, and 22 important plant species.[25]

- The Lal Suhanra Biosphere Reserve and National Park is a UNESCO declared biosphere reserve,[26] which covers 65,791 hectares (254.02 sq mi) the Cholistan region of the Greater Thar Desert.[27]

Biodiversity

[edit]Fauna

[edit]Some wildlife species that are fast vanishing in other parts of India are found in the desert in large numbers, including the blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), chinkara (Gazella bennettii), and Indian wild ass (Equus hemionus khur) in the Rann of Kutch. This may be partly because they are well adapted to this environment: they are smaller than similar animals that live in other environments, and they are mainly nocturnal. It may also be because grasslands in this region have not been transformed into cropland as fast as in other regions, and because a local community, the Bishnois, has made special efforts to protect them.

Other mammals in the Thar Desert include a subspecies of red fox (Vulpes vulpes pusilla) and the caracal, and a number of reptiles dwell there too.

The region is a haven for 141 species of migratory and resident desert birds, including harriers, falcons, buzzards, kestrels, vultures, short-toed eagles (Circaetus gallicus), tawny eagles (Aquila rapax), greater spotted eagles (Aquila clanga), and laggar falcons (Falco jugger).

The Indian peafowl is a resident breeder in the Thar region. The peacock is designated as the national bird of India and the provincial bird of the Punjab (Pakistan). It can be seen sitting on khejri or pipal trees in villages.

The Great Indian Bustard (Ardeotis nigriceps), one of the world’s heaviest flying birds, inhabits the Thar Desert of Rajasthan. Critically endangered, it thrives in open grasslands and semi-arid regions.

-

Peacock on a khejri tree

-

Peafowl eating pieces of chapati in Tharparkar District, Sindh

-

Blackbuck male and female

-

The chinkara or Indian gazelle is found across the Thar Desert.

Flora

[edit]

The natural vegetation of this dry area is classified as northwestern thorn scrub forest (i.e. small, loosely-scattered patches of greenery).[28][29] The densities and sizes of these green patches increase from west to east, following an increase in rainfall. The primary vegetation of the Thar Desert is composed of trees, shrubs, and perennial herb species, including:[30]

- Trees and shrubs: Aerva javanica, Balanites roxburghii, Calotropis procera, Capparis decidua, Clerodendrum multiflorum, Commiphora mukul, Cordia sinensis, Crotalaria burhia, Euphorbia caducifolia, Euphorbia neriifolia, Grewia tenax, Leptadenia pyrotechnica, Lycium barbarum, Maytenus emarginata, Mimosa hamata, Suaeda fruticosa, Vachellia jacquemontii, Ziziphus nummularia and Z. zizyphus.

- Herbs and grasses: Ochthochloa compressa, Dactyloctenium scindicum, Cenchrus biflorus, Cenchrus setiger, Lasiurus scindicus, Cynodon dactylon, Panicum turgidum, Panicum antidotale, Dichanthium annulatum, Sporobolus marginatus, Saccharum spontaneum, Cenchrus ciliaris, Desmostachya bipinnata, Eragrostis species, Ergamopagan species, Phragmites species, Tribulus terrestris, Typha species, Sorghum halepense, Citrullus colocynthis

The endemic floral species include Calligonum polygonoides, Prosopis cineraria, Acacia nilotica, Tamarix aphylla, and Cenchrus biflorus.[31]

History

[edit]The Desert National Park in Jaisalmer district has a collection of 180-million-year-old animal and plant fossils. The historical foundations of Jaisalmer State lie in the large empire ruled by the Bhati dynasty, which stretched from what is now Ghazni[32] in modern-day Afghanistan to what is Sialkot, Lahore and Rawalpindi in modern-day Pakistan[33] and extended to the region that is Bhatinda and Hanumangarh in modern-day India.[34]

According to Satish Chandra, the Hindu Shahis of Afghanistan made an alliance with the Bhatti rulers of Multhan to end the slave raids conducted by the Turkic ruler of Ghazni, but the alliance was broken apart by Alp Tigin in 977 CE. Bhati dominions continued to shift southwards: they ruled Multan, then finally got pushed into Cholistan and Jaisalmer, where Rawal Devaraja built Dera Rawal / Derawar.[35] Jaisalmer was founded as the new capital in 1156 by Maharawal Jaisal Singh and the state took its name from the capital. On 11 December 1818 Jaisalmer became a British protectorate through the Rajputana Agency.[36][37]

The kingdom’s economy, which had long depended on levies on caravans, declined after Bombay became a major port and sea trade largely replaced traditional land routes. Maharawals Ranjit Singh and Bairi Sal Singh attempted to reverse the economic decline, but the kingdom nevertheless became impoverished. Adding to the hardship, a severe drought and resulting famine from 1895 to 1900 during the reign of Maharawal Salivahan Singh caused widespread loss of livestock, upon which the increasingly agricultural kingdom had come to rely.

In 1965 and 1971, population exchanges took place in the Thar between India and Pakistan; 3,500 Muslims moved from the Indian section of the Thar to Pakistani Thar, while thousands of Hindu families migrated from Pakistani Thar to the Indian section.[38][39][40]

1 = ancient river

2 = today's river

3 = today's Thar desert

4 = ancient shore

5 = today's shore

6 = today's town

7 = paelochannels (Clift et al. (2012))

Population

[edit]The Thar people are the natives of the area. The Thar Desert is the most widely populated desert in the world, with a population density of 83 people per km2.[21] In India, the inhabitants comprise Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, and Muslims. In Pakistan, inhabitants include both Muslims and Hindus.[42]

About 40% of the total population of Rajasthan lives in the Thar Desert.[43] The main occupations of the inhabitants are agriculture and animal husbandry.

Jodhpur, the largest city in the region, lies in the scrub forest zone at the desert's perimeter. Bikaner and Jaisalmer are the largest cities located entirely in the desert.

-

A girl from the Gadia Lohars nomadic tribe of Marwar, cooking her food.

-

Thar life

-

Desert tribes near Jaisalmer, India

Water and housing in the desert

[edit]In the true desert areas, the only sources of water for animals or humans are small, scattered ponds - some that are natural (tobas) and some that are human-made (johads). The persistence of water scarcity heavily influences life in all areas of the Thar, prompting many inhabitants to adopt a nomadic lifestyle.[citation needed] Most of the permanent human settlements are located near the two seasonal streams of the Karon-Jhar hills. Potable groundwater is also rare in the Thar Desert. Much of it tastes sour due to dissolved minerals. Potable water is mostly available only deep underground. When wells are dug that happen to yield sweet tasting water, people tend to settle near them, but such wells are difficult and dangerous to dig, sometimes claiming the lives of the well-diggers.[citation needed]

Crowded housing conditions are common in some areas.

-

Huts in the Thar Desert

-

Johads are common water sources

-

Tanks for drinking water

Economy

[edit]Agriculture

[edit]The Thar is one of the most heavily populated desert areas in the world with the main occupations of its inhabitants being agriculture and animal husbandry.[44]

Agricultural production is mainly from kharif crops, which are grown in the summer season and seeded in June and July. These are then harvested in September and October and include bajra, pulses such as guar, jowar (Sorghum vulgare), maize (zea mays), sesame and groundnuts.

The Thar region of Rajasthan is a major opium production and consumption area.[45][46]

Livestock

[edit]-

Cattle in the Thar Desert

Agroforestry

[edit]

P. cineraria wood is reported to contain high calorific value and provide high-quality fuel wood. The lopped branches are good as fencing material. Its roots also encourage nitrogen fixation, which produces higher crop yields.

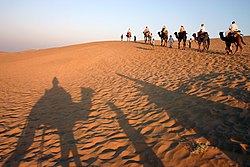

Ecotourism

[edit]Desert safaris on camels have become increasingly popular around Jaisalmer. Domestic and international tourists frequent the desert seeking adventure on camels for one to several days. This ecotourism industry ranges from cheaper backpacker treks to plush Arabian-Nights-style campsites replete with banquets and cultural performances. During the treks, tourists are able to view the fragile and beautiful ecosystem of the Thar Desert. This form of tourism provides income to many operators and camel owners in Jaisalmer, as well as employment for many camel trekkers in the desert villages nearby. People from various parts of the world come to see the Pushkar ka Mela (Pushkar Fair) and oases.

Industry

[edit]The government of India initiated departmental exploration for oil in 1955 and 1956 in the Jaisalmer area,[48] Oil India Limited discovered natural gas in 1988 in the Jaisalmer basin.[49]

See also

[edit]- List of deserts by area

- Cholistan Desert, in Pakistani Punjab

- Nara desert, in Sindh in Punjab

- Teri (geology), red sand desert of South India

- Great Rann of Kutch, Salt desert of India

- Glacial desert of India

- History of Thar

- Marwar

- Pokhran

- Thari people

- Cyclone Phet – tracked directly over the desert

Notes

[edit]- ^ See Clift et al. (2012) map and Honde te al. (2017) map.

- ^ In contrast to the mainstream view, Chatterjee et al. (2019) suggest that the river remained perennial till 4,500 years ago.

- ^ Giosan et al. (2012):

- "Contrary to earlier assumptions that a large glacier-fed Himalayan river, identified by some with the mythical Sarasvati, watered the Harappan heartland on the interfluve between the Indus and Ganges basins, we show that only monsoonal-fed rivers were active there during the Holocene."

- "Numerous speculations have advanced the idea that the Ghaggar-Hakra fluvial system, at times identified with the lost mythical river of Sarasvati (e.g., 4, 5, 7, 19), was a large glacier fed Himalayan river. Potential sources for this river include the Yamuna River, the Sutlej River, or both rivers. However, the lack of large-scale incision on the interfluve demonstrates that large, glacier-fed rivers did not flow across the Ghaggar-Hakra region during the Holocene

- "The present Ghaggar-Hakra valley and its tributary rivers are currently dry or have seasonal flows. Yet rivers were undoubtedly active in this region during the Urban Harappan Phase. We recovered sandy fluvial deposits approximately 5;400 y old at Fort Abbas in Pakistan (SI Text), and recent work (33) on the upper Ghaggar-Hakra interfluve in India also documented Holocene channel sands that are approximately 4;300 y old. On the upper interfluve, fine-grained floodplain deposition continued until the end of the Late Harappan Phase, as recent as 2,900 y ago (33) (Fig. 2B). This widespread fluvial redistribution of sediment suggests that reliable monsoon rains were able to sustain perennial rivers earlier during the Holocene and explains why Harappan settlements flourished along the entire Ghaggar-Hakra system without access to a glacier-fed river."

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Thar Desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545 [Supplemental material 2 table S1b]. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ a b c Sinha, R. K.; Bhatia, S. & Vishnoi, R. (1996). "Desertification control and rangeland management in the Thar desert of India". RALA Report No. 200: 115–123.

- ^ Sharma, K. K.; Mehra, S. P. (2009). "The Thar of Rajasthan (India): Ecology and Conservation of a Desert Ecosystem". In Sivaperuman, C.; Baqri, Q. H.; Ramaswamy, G.; Naseema, M. (eds.). Faunal Ecology and Conservation of the Great Indian Desert. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-87409-6_1. ISBN 978-3-540-87408-9.

- ^ "The Oldest Plant-Eating Dinosaur Has Been Found in India". The New York Times. 19 August 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Laity, J. J. (2009). Deserts and Desert Environments. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444300741.

- ^ Ramesh, R.; Jani, R. A. & Bhushan, R. (1993). "Stable isotopic evidence for the origin of salt lakes in the Thar desert". Journal of Arid Environments. 25 (1): 117–123. Bibcode:1993JArEn..25..117R. doi:10.1006/jare.1993.1047.

- ^ Gwen Robbins Schug, Subhash R. Walimbe (2016). A Companion to South Asia in the Past. John Wiley & Sons. p. 64. ISBN 978-1119055471. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ Sharma, K. K., S. Kulshreshtha, A. R. Rahmani (2013). Faunal Heritage of Rajasthan, India: General Background and Ecology of Vertebrates. Springer Science & Business Media, New York.

- ^ Kuhle, Matthias (1998). "Reconstruction of the 2.4 Million km2 Late Pleistocene Ice Sheet on the Tibetan Plateau and its Impact on the Global Climate". Quaternary International. 45/46: 71–108. Bibcode:1998QuInt..45...71K. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(97)00008-6.

- ^ Kuhle, M (2004). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and LGM) ice cover in High and Central Asia". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L. (eds.). Development in Quaternary Science 2c (Quaternary Glaciation – Extent and Chronology, Part III: South America, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica). pp. 175–99.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (1999). "Tibet and High Asia V. Results of Investigations into High Mountain Geomorphology, Paleo-Glaciology and Climatology of the Pleistocene". GeoJournal. 47 (1–2): 3–276. doi:10.1023/A:1007039510460. S2CID 128089823. See chapter entitled: "Reconstruction of an approximately complete Quaternary Tibetan Inland Glaciation between the Mt. Everest and Cho Oyu Massifs and the Aksai Chin. – A new glaciogeomorphological southeast-northwest diagonal profile through Tibet and its consequences for the glacial isostasy and Ice Age cycle".

- ^ Kuhle, M. (1988). "The Pleistocene Glaciation of Tibet and the Onset of Ice Ages – An Autocycle Hypothesis". GeoJournal. 17 (4): 581–96. doi:10.1007/BF00209444. S2CID 129234912. Tibet and High-Asia I. Results of the Sino-German Joint Expeditions (I).

- ^ Kuhle, Matthias (2001). "The Tibetan Ice Sheet; its Impact on the Palaeomonsoon and Relation to the Earth's Orbital Variations". Polarforschung. 71 (1/2): 1–13.

- ^ a b c Giosan et al. 2012.

- ^ a b Maemoku et al. 2013.

- ^ a b c Clift et al. 2012.

- ^ a b c Singh et al. 2017.

- ^ Sankaran 1999.

- ^ Rahmani, A. R. (1989). "The uncertain future of the Desert National Park in Rajasthan, India". Environmental Conservation. 16 (3): 237–244. doi:10.1017/S0376892900009322. S2CID 83995201.

- ^ a b c Singh, P. (ed.) (2007). "Report of the Task Force on Grasslands and Deserts" Archived 10 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Government of India Planning Commission, New Delhi.

- ^ WII (2015). Conservation Reserves Archived 10 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun.

- ^ Ghalib, S. A.; et al. (2008). "Bioecology of Nara Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, Districts Ghotki, Sukkur and Khairpur, Sindh". Pakistan Journal of Zoology. 40 (1): 37–43. ISSN 0030-9923.

- ^ a b "Protected Areas". Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Ghalib, S. A.; et al. (2014). "Current distribution and status of the mammals, birds and reptiles in Rann of Kutch Wildlife Sanctuary, Sindh". International Journal of Biology and Biotechnology (Pakistan). 10 (4): 601–611. ISSN 1810-2719. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Lal Suhanra". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ "UNESCO – MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory". unesco.org. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Champion, H. G.; Seth, S. K. (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India. Government of India Press. OCLC 549213.

- ^ Negi, S. S. (1996). Biosphere Reserves in India: Landuse, Biodiversity and Conservation. Delhi: Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 9788173870439.

- ^ Kaul, R. N. (1970). Afforestation in arid zones. Monographiiae Biologicae. Vol. 20. The Hague. OCLC 115047.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Khan, T. I. & Frost, S. (2001). "Floral biodiversity: a question of survival in the Indian Thar Desert". Environmentalist. 21 (3): 231–236. doi:10.1023/A:1017991606974. S2CID 82472637.

- ^ "Rajasthan or the Central and Western Rajpoot States, Volume 2, page 197-198". Higginbotham And Co. Madras. 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Imperial Gazetter of India, Volume 21, page 272 - Imperial Gazetteer of India - Digital South Asia Library". Dsal.uchicago.edu. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Bhatinda Government: District at A glance- Origin". Bhatinda Government. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Provincial Gazetteers Of India: Rajputana". Government of India. 14 August 2018.

- ^ "Princely States of India".

- ^ "Provincial Gazetteers Of India: Rajputana". Government of India. 14 August 2018.

- ^ Hasan, Arif; Raza, Mansoor (2009). Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan. IIED. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9781843697343.

- ^ Maini, Tridivesh Singh (15 August 2012). "Not just another border". Himal South Asian.

- ^ Arisar, Allah Bux (6 October 2015). "Families separated by Pak-India border yearn to see their loved ones". News Lens Pakistan. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ See map

- ^ Raza, Hassan (5 March 2012). "Mithi: Where a Hindu fasts and a Muslim does not slaughter cows". Dawn.

- ^ Gupta, M. L. (2008). Rajasthan Gyan Kosh. 3rd Edition. Jojo Granthagar, Jodhpur. ISBN 81-86103-05-8

- ^ Raza, Fawwad (31 March 2021). "Modern Agriculture Techniques in the Desert of THAR - Scientia Magazine". Retrieved 1 November 2024.

- ^ "ICMR Bulletin vol.38, No.1-3, Pattern and Process of Drug and Alcohol Use in India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Will Rajasthan opium farmers vote for change?". Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Breeds of Livestock - Tharparkar Cattle — Breeds of Livestock, Department of Animal Science". afs.okstate.edu. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "PlanningCommission.NIC.in". Archived from the original on 14 April 2006. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ OilIndia.NIC.in Archived 30 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

Web

[edit]- ^ Mythical Saraswati River, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, 20 March 2013.Archived 9 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

[edit]- Chatterjee, Anirban; Ray, Jyotiranjan S.; Shukla, Anil D.; Pande, Kanchan (20 November 2019). "On the existence of a perennial river in the Harappan heartland". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 17221. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917221C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53489-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6868222. PMID 31748611.

- Clift, Peter D.; Carter, Andrew; Giosan, Liviu; Durcan, Julie; et al. (2012), "U-Pb zircon dating evidence for a Pleistocene Sarasvati River and capture of the Yamuna River", Geology, 40 (3): 211–214, Bibcode:2012Geo....40..211C, doi:10.1130/g32840.1, S2CID 130765891

- Giosan; et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization". PNAS. 109 (26): E1688 – E1694. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109. PMC 3387054. PMID 22645375.

- Giosan, Liviu; Clift, Peter D.; Macklin, Mark G.; Fuller, Dorian Q. (10 October 2013). "Sarasvati II". Current Science. 105 (7): 888–890. JSTOR 24098502.

- Khonde, Nitesh; Kumar Singh, Sunil; Maur, D. M.; Rai, Vinai K.; Chamyal, L. S.; Giosan, Liviu (2017), "Tracing the Vedic Saraswati River in the Great Rann of Kachchh", Scientific Reports, 7 (1): 5476, Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.5476K, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05745-8, PMC 5511136, PMID 28710495

- Maemoku, Hideaki; Shitaoka, Yorinao; Nagatomo, Tsuneto; Yagi, Hiroshi (2013). "Geomorphological Constraints on the Ghaggar River Regime During the Mature Harappan Period". In Giosan, Liviu; Fuller, Dorian Q.; Nicoll, Kathleen; Flad, Rowan K.; Clift, Peter D. (eds.). Climates, Landscapes, and Civilizations. American Geophysical Union Monograph Series 198. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-70443-1.

- Sankaran, A. V. (25 October 1999). "Saraswati – The ancient river lost in the desert". Current Science. 77 (8): 1054–1060. JSTOR 24103577. Archived from the original on 19 September 2004.

- Singh, Ajit; et al. (2017). "Counter-intuitive influence of Himalayan river morphodynamics on Indus Civilisation urban settlements". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1617. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1617S. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01643-9. PMC 5705636. PMID 29184098.

- Valdiya, K.S. (2013). "The River Saraswati was a Himalayan-born river" (PDF). Current Science. 104 (1): 42.

Further reading

[edit]- Bhandari M. M. Flora of The Indian Desert, MPS Repros, 39, BGKT Extension, New Pali Road, Jodhpur, India.

- Zaigham, N. A. (2003). "Strategic sustainable development of groundwater in Thar Desert of Pakistan". Water Resources in the South: Present Scenario and Future Prospects, Commission on Science and Technology for Sustainable Development in the South, Islamabad.

- Govt. of India. Ministry of Food & Agriculture booklet (1965)—"Soil conservation in the Rajasthan Desert"—Work of the Desert Afforestation Research station, Jodhpur.

- Gupta, R. K. & Prakash Ishwar (1975). Environmental analysis of the Thar Desert. English Book Depot., Dehra Dun.

- Kaul, R. N. (1967). "Trees or grass lands in the Rajasthan: Old problems and New approaches". Indian Forester, 93: 434–435.

- Burdak, L. R. (1982). "Recent Advances in Desert Afforestation". Dissertation submitted to Shri R. N. Kaul, Director, Forestry Research, F.R.I., Dehra Dun.

- Yashpal, Sahai Baldev, Sood, R.K., and Agarwal, D.P. (1980). "Remote sensing of the 'lost' Saraswati river". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences (Earth and Planet Science), V. 89, No. 3, pp. 317–331.

- Bakliwal, P. C. and Sharma, S. B. (1980). "On the migration of the river Yamuna". Journal of the Geological Society of India, Vol. 21, Sept. 1980, pp. 461–463.

- Bakliwal, P. C. and Grover, A. K. (1988). "Signature and migration of Sarasvati river in Thar desert, Western India". Record of the Geological Survey of India V 116, Pts. 3–8, pp. 77–86.

- Rajawat, A. S., Sastry, C. V. S. and Narain, A. (1999-a). "Application of pyramidal processing on high resolution IRS-1C data for tracing the migration of the Saraswati river in parts of the Thar desert". in "Vedic Sarasvati, Evolutionary History of a Lost River of Northwestern India", Memoir Geological Society of India, Bangalore, No. 42, pp. 259–272.

- Ramasamy, S. M. (1999). "Neotectonic controls on the migration of Sarasvati river of the Great Indian desert". in "Vedic Sarasvati, Evolutionary History of a Lost River of Northwestern India", Memoir Geological Society of India, Bangalore, No. 42, pp. 153–162.

- Rajesh Kumar, M., Rajawat, A. S. and Singh, T. N. (2005). "Applications of remote sensing for educidate the Palaeochannels in an extended Thar desert, Western Rajasthan", 8th annual International conference, Map India 2005, New Delhi.

External links

[edit] Thar Desert travel guide from Wikivoyage

Thar Desert travel guide from Wikivoyage- "Thar Desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Dharssi.org.uk, Photos of the Thar Desert

- Avgustin.net, Photos of the Thar Desert in Pakistan side

KSF

KSF