The Artist in His Museum

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

| The Artist in His Museum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Charles Willson Peale |

| Year | 1822 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 262.9 cm × 203.2 cm (103.5 in × 80 in) |

| Location | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia |

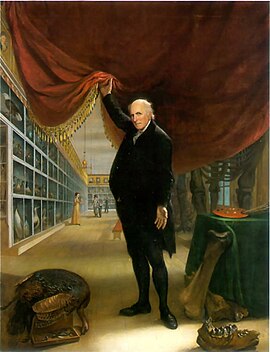

The Artist in His Museum is an 1822 self-portrait by the American painter Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827). It depicts the 81-year-old artist posed in Peale's Museum, then occupying the second floor of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1] The nearly life-size painting is in the collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

History

[edit]Toward the end of his career, beginning in 1822, he painted seven self-portraits that together formed the final motif of his art and the final flourishing of his talent. The Artist in His Museum is a large-scale oil-on-canvas work painted in about two months, and is the most emblematic of Peale's many self-portraits.

Peale was a naturalist as well as a painter. In 1784 he founded the Philadelphia Museum, situated at the time of the painting in the Long Room of the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall). The curation of the museum dominated his career from that point; he would on occasion announce his retirement from painting or his return to it.

In 1822 he was asked by the museum's trustees to paint a full-length portrait of himself for the museum. The artist endeavored to "not only make it a lasting monument of my art as a Painter, but also that the design should be expressive, that I bring forth into public view, the beauties of Nature and Art, the rise & progress of the Museum."[2] He further said, "I wish it may excite some admiration, otherwise my labor is lost, except that it is a good likeness."[3] Peale's determination to honor his career is reflected in his having painted two preliminary versions of The Artist, unusual for an artist who took pride in producing likenesses with little preparatory work.

Description

[edit]

There are three spaces in the work. The foreground of the painting depicts in low light some natural objects of the museum. At the front left, a dead wild turkey sits with Peale's taxidermic tools, brought back by his son Titian and waiting to join the collection to reveal its meaning as a national symbol. Another American symbol, the bald eagle, is higher on the left edge of the canvas, mounted by Peale—"the strength of the Eagles Eye is really astonishing"—and is now one of his few surviving specimens.[4] On the extreme left is an early donation: a paddlefish from the Allegheny River in an upright case, marked "With this article the Museum commenced, June, 1784".[5] To Peale's left lie the bones of a mastodon; the assembled skeleton that shows from behind the curtain was the museum's main attraction. Peale had unearthed and reconstructed a mastodon in 1800, an event he chronicled in his 1806 painting Exhuming the First American Mastodon (left). The artist's palette and brushes to his left contribute to the autobiographical statement.

The middle ground highlights Peale. In the painting, the artist invites the viewer into his museum; he pulls back a draped crimson curtain, which divides the painting's space, to reveal the collection. He used a similar motif on the printed acknowledgments he sent to museum donors, on which a curtain labeled "Nature" is held back to reveal a landscape with animals.[4] According to critic David C. Ward, the positioning of Peale "has the effect of creating a dialectic between life and art, painter and audience, the individual and American culture at large, and finally past and present. The figure of Peale bridges these realms … further drawing attention to and heightening the impact of his creativity."

The deep background behind the curtain gives the portrait its unique significance. Peale collected thousands of specimens of birds and other animals for his museum by soliciting donations or hunting them himself. The museum's receding shelves display animal species organized by Linnaean classification, and above them are portraits of revolutionary heroes and other notable Americans, whose placement suggests the position of humans in the great chain of being.[4] Peale believed that physiognomy, whether of humans in portraits or of animal specimens, provided insight into character.[4] To Peale, the behavior of animals served as a model for a moral, productive, and socially harmonious society.[4] In the far background a child represents posterity benefiting from the museum's lessons in natural history.[2] Likewise the woman nearer to the foreground represents the museum's power to inspire feelings of awe and wonder in the face of the sublime. Yet as the space recedes, so does Peale's life and the intellectual and scientific culture of the time—the American Enlightenment.

References

[edit]- ^ Admission ticket to Peale's Museum from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ a b Miller, Lillian B. (1990). "Charles Willson Peale" in James Vinson (ed.), International Dictionary of Art and Artists vol. 2, Art. Detroit: St. James Press; pp. 622–23. ISBN 1-55862-001-X.

- ^ Ward, David C. (Winter 1993). "Celebration of Self: The Portraiture of Charles Willson Peale and Rembrandt Peale, 1822-27". American Art. 7 (1): 8–27. doi:10.1086/424174.

- ^ a b c d e Brigham, David R. (1996). "'Ask the Beasts, and They Shall Teach Thee': The Human Lessons of Charles Willson Peale's Natural History Displays". The Huntington Library Quarterly. 59 (2/3): 182–206. doi:10.2307/3817666. JSTOR 3817666.

- ^ Alexander, Edward Porter (1995). Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence. Rowman Altamira. p. 45. ISBN 0-7619-9131-X.

External links

[edit]- The Artist in His Museum from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

KSF

KSF