The Robbers

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 19 min

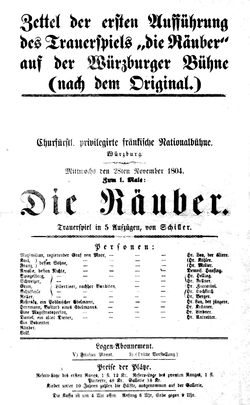

| Die Räuber The Robbers | |

|---|---|

First edition of the play | |

| Written by | Friedrich Schiller |

| Date premiered | 13 January 1782 |

| Place premiered | Mannheim |

| Original language | German |

| Genre | Tragedy |

The Robbers (Die Räuber, German pronunciation: [diː ˈʁɔʏbɐ] ⓘ) is the first dramatic play by German playwright Friedrich Schiller. The play was published in 1781 and premiered on 13 January 1782 in Mannheim and was inspired by Leisewitz's earlier play Julius of Taranto. It was written towards the end of the German Sturm und Drang ("Storm and Stress") movement, and many critics, such as Peter Brooks, consider it very influential in the development of European melodrama.[1] The play astounded its Mannheim audience and made Schiller an overnight sensation. It later became the basis for Verdi's opera of the same name, I masnadieri.

Plot and description

[edit]The plot revolves around the conflict between two aristocratic brothers, Karl and Franz Moor. The charismatic but rebellious student Karl is deeply loved by his father. The younger brother, Franz, who appears as a cold, calculating villain, plots to wrest away Karl's inheritance. As the play unfolds, both Franz's motives and Karl's innocence and heroism are revealed to be complex.

Schiller's highly emotional language and his depiction of physical violence mark the play as a quintessential Sturm und Drang work.[citation needed] At the same time, the play utilizes a traditional five-act structure, with each act containing two to five scenes. The play uses alternating scenes to pit the brothers against each other, as one quests for money and power, while the other attempts to create revolutionary anarchy in the Bohemian Forest.

Schiller raises many disturbing issues in the play. For instance, he questions the dividing lines between personal liberty and the law and probes the psychology of power, the nature of masculinity and the essential differences between good and evil. He strongly criticizes both the hypocrisies of class and religion and the economic inequities of German society. He also conducts a complicated inquiry into the nature of evil.

Schiller was inspired by the play Julius of Taranto (1774) by Johann Anton Leisewitz, a play Friedrich Schiller considered a favourite.[2]

Content

[edit]Summary

[edit]Count Maximilian of Moor has two very different sons, Karl and Franz. Karl is the elder son, and the count's favourite. In comparison, Franz is described as ugly, and he was neglected during his childhood. As the younger son, he has no claim of inheritance from his father. Franz spends his time in the play scheming to remove Karl as well as the count. At the beginning of the play, Karl is a student in Leipzig, where he lives a relatively carefree life, spending freely, accruing large amounts of debt. He writes to his father in hopes of reconciliation.

Franz uses the letter as an opportunity to push a false narrative of Karl's life on his father. Throwing away the original letter, Franz writes a new one that claims to be from a friend, describing in the barest terms the types of activities Karl is claimed to be doing in Leipzig. The letter describes Karl as a womanizer, murderer, and thief. The letter shocks the old count deeply, causing him to declare — with the help of Franz's suggestions — Karl as disinherited.

Karl, having hoped for a reconciliation, becomes demotivated at the news. He agrees to become the head of a robbers band that his friends created, in the idealistic hopes of protecting the weaker and being an "honourable" robber. There are tensions in the band, as Moritz Spiegelberg tries to sow discord among them. Spiegelberg hopes to be the leader of the group and tries to encourage the rest to replace Karl. Karl falls into a cycle of violence and injustice, which prevents him from returning to his normal life. He eventually swears to stay forever with his band of robbers. Shortly after, the band receives a newcomer, Kosinsky, who tells them the tale of how his bride-to-be, importantly named Amalia, was stolen from him by a greedy count. This reminds Karl of his own Amalia, and he decides to return to his father's home, disguised.

In this time, Franz has been busy. Using lies and exaggerations about Karl, he manages to break the count's heart and assumes the mantle of the new Count of Moor. Bolstered by his new title and jealous of Karl's relationship with Amalia, he attempts to persuade her to marry him. Amalia, however, stays true to Karl and denies Franz's advances. She sees through his lies and exaggerations about Karl.

Karl returns home, disguised, and finds the castle very different from how he left it. Franz introduces himself as the count, and with some careful questions, Karl learns that their father has died, and Franz has taken his place. Despite Karl's carefulness, Franz has his suspicions. In a moment with Amalia — who does not recognize him — he learns that Amalia still loves him.

Franz explores his suspicions about the identity of his guest. Karl leaves the castle. He runs into an old man, who turns out to be his father — he is alive. The old count was left to starve in an old ruin and in his weakness is unable to recognize Karl. Incensed by the treatment of his loved ones, Karl sends his robbers band to storm the castle and capture Franz. Franz observes the robbers approaching and takes his own life before he can be captured. The robbers take Amalia from the castle and bring her to Karl. Seeing that Karl is alive, Amalia is initially happy. Once the old count realizes that Karl is the robbers' leader, he in his weakened state dies from the shock. Karl tries to leave the robber band but is then reminded of his promise to stay. He cannot break this promise and therefore cannot be with Amalia. Upon realizing that Karl cannot leave, Amalia begs for someone to kill her; she cannot live without her Karl. With a heavy heart, Karl fulfills her wish. As the play ends, Karl decides to turn himself over to the authorities.

First Act

[edit]The first act takes place in the Castle of the Count of Moor. The key characters are the Count of Moor and his younger son Franz. Not in scene, but mentioned, is the count's older son, Karl. Karl is a student in Leipzig, who lives freely but irresponsibly.

First Scene

[edit]The old Count Maximilian of Moor receives a letter from Leipzig, containing news about his older son Karl. The content, however, as read by his younger son, Franz, is upsetting. Supposedly written by a friend of Karl's, it describes how Karl accrued massive debts, deflowered the daughter of a rich banker whose fiancé he killed in a duel, and then ran from the authorities. Unknown to the count, the letter was written by Franz himself – the content entirely false – with Karl's actual letter destroyed. Greatly disturbed by the news, the count takes some supposedly "friendly advice" from Franz and disowns Karl. The count hopes that such a drastic measure would encourage Karl to change his behavior, and upon his doing so, the count would be glad to have Karl back. The count has Franz write the letter and impresses upon him to break the news gently. Franz, however, writes an especially blunt letter as a way of driving a deeper wedge between Karl and his father.

Second Scene

[edit]At the same time as Scene 1, Karl and a friend of his, Spiegelberg, are drinking at a pub. With the arrival of a few more friends comes the arrival of Franz's letter to Karl. Upon reading the message, Karl lets the letter fall to the ground and leaves the room speechless. His friends pick it up and read it. In Karl's absence, Spiegelberg suggests that the group become a robber's band. Karl returns, and is obviously disillusioned from the bluntness of his father's letter. His friends ask that he become the leader of their robber's band, and Karl agrees. They formulate a pact, swearing to be true to each other and the band. The only discontent comes from Spiegelberg, who had hoped to be the leader.

Third Scene

[edit]In this scene Franz visits Amalia. Amalia is engaged to Karl. Franz lies to her, hoping to make her disgusted with Karl and to win her for himself. He tells her Karl gave away the engagement ring she gave him so that he could pay a prostitute. This extreme character change, as presented in Franz's story, causes Amalia to doubt the truth of it, and she remains true to Karl. She sees through Franz's lies and realizes his true intentions. She calls him out, and he lets his "polite" mask fall and swears revenge.

Second Act

[edit]First Scene

[edit]Franz begins setting the foundations of his greater plan of removing both Karl and the count. He hopes to shock the old count so greatly that he dies. He encourages Herman, a bastard, to tell the old count a story about Karl. He promises that Herman will receive Amalia in return for his help. Herman leaves the room to carry out the plan, and just as he's left, Franz reveals that he has no intention of holding up his end of the promise. Franz wants Amalia for himself.

Second Scene

[edit]Herman arrives to the castle in disguise. He tells the old count that he and Karl were both soldiers, and that Karl died in battle. He follows with Karl's supposed last words, placing the blame on the old count's shoulders. The old man is shocked and receives only harsh words from Franz. He cannot stand it, and falls to the floor, apparently dead. Franz takes up the title and warns of a darker time to come for the people on his land.

Third Scene

[edit]During this time, Karl is living life as the Leader of the robber's band. They are camped in the Bohemian forests. The band is growing, with new members coming in. The loyalty of the robbers to Karl grows too, Karl has just rescued one of their own, Roller, from being hanged. The escape plan is carried out by setting the town ablaze which ultimately destroys the town and kills 83 people. In the forest, they are surrounded by a large number of soldiers, and a priest is sent to give an ultimatum – give up Karl and the robbers live, or everyone dies. The robbers, however, stay true to their leader and with the cry "Death or Freedom!" the fight breaks out, ending the second Act.

Third Act

[edit]First Scene

[edit]Franz seeks again to force Amalia to join him. He tells her that her only other option would be to be placed at a convent. This hardly bothers Amalia, she would rather be in a convent than be Franz's wife. This angers Franz and he threatens to take her forcefully, menacing her with a knife. Amalia feigns a change of heart, embracing Franz, and uses it as an opportunity to take the weapon. She turns it on Franz, promising the union of the two, knife and Franz, if he threatens her again.

Second Scene

[edit]After a long and exhausting battle, the robbers are victorious. Karl takes a moment to reflect on his childhood, and his recent actions. In this moment, Kosinsky, a newcomer, arrives in scene. He wishes to join the robbers, but Karl encourages him not to. Karl tells him to return to normal life, that becoming a robber would be damaging. Kosinsky presses the matter, and describes what caused him to want to be a robber. His story shares many points with Karl's, especially that Kosinsky also had a fiancee by the name of Amalia. Kosinsky's story ends with the loss of his Amalia to his count. Karl, seeing perhaps a sliver of his upcoming fate, decides to return home. His robbers, now including Kosinsky, follow him.

Fourth Act

[edit]First Scene

[edit]Karl arrives to his homeland, and tells Kosinsky to ride to the castle and introduce Karl as the Count of Brand. Karl shares some memories of his childhood and youth, brought forth by the familiar scenery, but his monologue becomes progressively darker. He feels a moment of doubt regarding the sensibility of his return, but he gathers his courage and enters the castle.

Second Scene

[edit]The disguised Karl is led by Amalia through the castle halls. She is unaware of his true identity. Franz, however, is suspicious of the strange Count of Brand. He attempts to get one of his servants, Daniel, to poison the stranger, but Daniel refuses on account of his conscience.

Third Scene

[edit]Daniel recognizes Karl from an old scar of his. They discuss the goings-on of the castle and Karl learns of the plot that Franz has carried out against Karl and his father. Karl wishes to visit Amalia once more before he leaves. He isn't concerned with vengeance at this point.

Fourth Scene

[edit]In a last meeting with Amalia, who still does not recognize Karl, the two discuss their lost loves. Karl discusses the reality of his actions, in their violence, and explains that he cannot return to his love because of them. Amalia is happy that her Karl is alive, despite his distance, and describes him as a purely good person. Karl breaks character at Amalia's faith in him, and flees the castle, returning to his robbers nearby.

Fifth Scene

[edit]In Karl's absence, Spiegelberg makes another attempt to rally the robbers against Karl so he can be their leader. The robbers remain loyal to Karl and Schweizer, one of his close friends, kills Spiegelberg for this attempt. Karl returns to the band, and is asked what they should do. He tells them to rest, and in this time he sings a song about a confrontation between the dead Caesar and his murderer Brutus. The song discusses patricide, this coming from a legend in which Brutus was possibly Caesar's son. This topic reminds Karl of his own situation, and he falls into depressive thoughts. He considers suicide, but ultimately decides against it.

In the same night, Herman enters the forest, delivering food to an old and ruined tower. In the tower, the old Count of Moor is left to starve following the unsuccessful attempt on his life. Karl notices this, and frees the old man and recognizes him as his father. His father does not recognize him. The old man tells Karl what happened to him, how Franz treated him. Karl becomes full of rage upon hearing the story, and calls his robbers to storm the castle and drag out Franz.

Fifth Act

[edit]First Scene

[edit]That same night, Franz is plagued by nightmares. Disturbed and full of fear, he hurries about the castle, meeting Daniel whom he orders to fetch the pastor. The pastor arrives, and the two have a long dispute over belief and guilt, in which the pastor's opinions are explained. Franz asks the pastor what he believes the worst sin is, and the pastor explains that patricide and fratricide are the two worst, in his opinion. But of course, Franz has no need to worry, since he has neither a living father or brother to kill. Franz, aware of his guilt, sends the pastor away and is disturbed by the conversation. He hears the robber's approach and knows, from what he hears, that they are there for him. He attempts to pray, but is unable to, and begs Daniel to kill him. Daniel refuses to do so, so Franz takes the matter into his own hands and kills himself.

Second Scene

[edit]The old count, still unaware of Karl's identity, laments the fates of his sons. Karl asks for the blessing of his father. The robbers bring Amalia to their camp, and Karl announces his identity as Karl of Moor and the robber's leader. This news is the final straw for the weakened old count, and he finally dies. Amalia forgives Karl and expresses that she still wants to be with him. Karl is bound by his promise to the robber band, and cannot leave. Amalia will not live without Karl, so she begs that someone kill her. One of the robbers offers to do so, but Karl insists that he do it. Karl kills her, and regrets his promise to the band. He decides to do something good by turning himself in to a farmer he met whose family was starving. The farmer would receive the reward money and be able to support his family.

Dramatis personae

[edit]

- Maximilian, Count von Moor (also called "Old Moor") is the beloved father of Karl and Franz. He is a good person at heart, but also weak, and has failed to raise his two sons properly. He bears responsibility for the perversion of the Moor family, which has caused the family's values to become invalidated. The Moor family acts as an analogy of state, a typical political criticism of Schiller's.

- Karl (Charles) Moor, his older son, is a self-confident idealist. He is good-looking and well liked by all. He holds feelings of deep love for Amalia. After his father, misled by brother Franz, curses Karl and banishes him from his home, Karl becomes a disgraceful criminal and murderous arsonist. While he exudes a general spirit of melancholy about the promising life he has left behind, Karl, together with his gang of robbers, fights against the unfairness and corruption of the feudal authorities (his character follows the literary archetype of the noble outlaw[3]). His despair leads him to express and discover new goals and directions, and to realize his ideals and dreams of heroism. He does not shrink from breaking the law, for, as he says, "the end justifies the means". He develops a close connection with his robbers, especially Roller and Schweizer, but he recognizes the unscrupulousness and dishonor of Spiegelberg and his other associates. Amalia creates a deep internal twist in the plot and in Karl's persona. He swore allegiance to the robbers after Schweizer and Roller died for his sake, and he promised that he would never separate from his men, so cannot return to Amalia. In deep desperation due to the death of his father, he eventually kills his true love and decides to turn himself in to the law.

- Franz Moor, the count's younger son, is an egoistic rationalist and materialist. He is cold-hearted and callous. He is rather ugly and unpopular, in contrast to his brother Karl, but quite intelligent and cunning. However, since his father loved only his brother and not him, he developed a lack of feeling, which made the "sinful world" intolerable for his passions. Consequently, he fixed himself to a rationalistic way of thinking. In the character of Franz, Schiller demonstrates what could happen if the moral way of thinking were replaced by pure rationalization. Franz strives for power in order to be able to implement his interests.

- Amalia von Edelreich, the count's niece, is Karl's love, and a faithful and reliable person (to learn more of their relationship see "Hektorlied" (de)). She spends most of the play avoiding the advances of the jealous Franz and hopes to be rejoined with her beloved Karl.

- Spiegelberg acts as an opponent of Karl Moor and is driven by crime. Additionally, he self-nominated himself to be captain in Karl's robber band, yet was passed up in favor of Karl. Spiegelberg tries to portray Karl negatively among the robbers in order to become the captain, but does not succeed.

Other characters

- Schweizer

- Grimm

- Razmann

- Schufterle

- Roller

- Kosinsky

- Schwarz

- Herrmann, the illegitimate son of a Nobleman

- Daniel, an old servant of Count von Moor

- Pastor Moser

- Pater

- A Monk

- Band of robbers, servants, etc.

Inspiration

[edit]The family of Treusch von Buttlar at Willershausen, around 1730/40, served as an inspiration and background to his drama.

One source of The Robbers was Christian Schubart's Zur Geschichte des menschlichen Herzens [Concerning the History of the Human Heart] (1775) as well as the real-life story about the case of two Treusch von Buttlar brothers. The older good brother Ernst Carl and the evil younger brother Hans Hermann Wilhelm. This was one of the greatest social and legal scandals in early eighteen century Franconia.

Major Wilhelm von Buttlar married Eva Eleonora von Lentersheim at Obersteinbach castle (Obersteinbach website refers to him as Franz). Her father Erhard von Lentersheim was an epileptic and alcoholic. He was put under a guardianship. As the son-in-law, Wilhelm exercised the right of disposing of his goods to himself. Additionally, to further benefit Wilhelm because Wilhelm's mother-in-law, Louisa von Lentersheim (née von Eyb), had property of her own, Wilhelm had her strangled on December 7, 1727, by a servant. While the trial lasted for years, it did not end in conviction. Schiller also went to school with Wilhelm Philipp Johann Ludwig von Bibra (Adelsdorf) (1765–1794) at the Carlsakademie. As a close relative of the murdered mother-in-law, Wilhelm von Bibra may have spurred Schiller's interest in the incident.[4][5][6][7]

Legacy

[edit]The play is referred to in Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. Fyodor Karamazov compares himself to Count von Moor, whilst comparing his eldest son, Dmitri, to Franz Moor, and Ivan Karamazov to Karl Moor.[8] It is also referred to in the first chapter of Ivan Turgenev's First Love [9] and briefly in chapter 28 of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre.[10] G. W. F. Hegel in his The Phenomenology of Spirit is thought to model the 'law of the heart' after Karl Moor. This was first suggested by Jean Hyppolite[11] and by others more recently.[12]

English translations

[edit]Peter Newmark notes three translations in the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation:[13]

- The Robbers. Translated by Alexander Fraser Tytler. G. G. & J. Robinson. 1792. Public domain; widely available in many formats.

- The Robbers, with Wallenstein. Translated by F. J. Lamport. Penguin. 1979. ISBN 978-0-14-044368-4.

- The Robbers. Translated by Robert David MacDonald. Oberon. 1995. ISBN 978-1-870259-52-1. The same translation apparently also appears in Schiller: Volume One: The Robbers, Passion and Politics. Translated by Robert David MacDonald. Oberon. 2006. ISBN 978-1-84002-618-4.

- Millar, Daniel and Leipacher, Mark (2010). The Robbers (unpublished). Presented by the Faction Theatre Company.[14]

Klaus van den Berg has compared the Lamport and MacDonald translations, "The two most prominent translations from the latter part of the twentieth century take very different approaches to this style: F. J. Lamport's 1979 translation, published in the Penguin edition, follows Schiller's first epic-sized version and remains close to the original language, observing sentence structures, finding literal translations that emphasize the melodramatic aspect of Schiller's work. In contrast, Robert MacDonald's 1995 translation, written for a performance by the Citizen's Company at the Edinburgh Festival, includes some of Schiller's own revisions, modernizes the language trying to find equivalences to reach his British target audiences. While Lamport directs his translation toward an audience expecting classics as authentic as possible modelled on the original, McDonald opts for a performance translation cutting the text and interpreting many of the emotional moments that are left less clear in a more literal translation."[15]

Michael Billington wrote in 2005 that Robert MacDonald "did more than anyone to rescue Schiller from British neglect."[16]

Adaptations

[edit]- The Red-Cross Knights (1799), play by Joseph George Holman

- I briganti (1836), opera by Saverio Mercadante and libretto by Jacopo Crescini

- I masnadieri (1847), opera by Giuseppe Verdi and libretto by Andrea Maffei

- I briganti (ca. 1895), opera by Lluïsa Casagemas (op. 227) and libretto by Andrea Maffei. Not published or performed.[citation needed]

- The Robbers (1913), film adaptation by J. Searle Dawley and Walter Edwin.[17]

- Die Räuber (1957), opera and libretto by Giselher Klebe.[18]

- Death or Freedom (1977), loosely based German film adaptation with Gert Fröbe and Peter Sattmann

- Gending Sriwijaya (2013), Indonesian film adaptation by Hanung Bramantyo

Lieder

[edit]- "Amalia", D 195, Op. post. 173 No. 1, is a lied by Franz Schubert based on text from act 3, scene 1.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Stephanie Barbé Hammer, Schiller's Wound: The Theater of Trauma from Crisis to Commodity (Wayne State University Press, 2001), page 32.

- ^ Johann Anton Leisewitz, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Babinski, Hubert F. (1979). "Reviewed Work(s): A Criminal as Hero: Angelo Duca by Paul F. Angiolillo". Italica. 56 (3): 307–309.

- ^ Schwinger, Hans (2020). Die Schwebheimer Linie derer von Bibra und ihr Ende. Books on Demand. p. 26.

- ^ Martinson, Steven D. (2005). A Companion to the Works of Friedrich Schiller. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 93–99. ISBN 9781571131836.

- ^ "Die Schlossgeschichte". schullandheimwerk-mittelfranken.de (in German).

- ^ Bibra, Wilhelm von (1888). Beiträge zur Familien-Geschichte der Reichsfreiherrn von Bibra (in German). Vol. 3. pp. 103–104.

- ^ Fyodor Dostoevsky. "The Brothers Karamazov". Retrieved 20 June 2011.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Ivan Turgenev. "First Love". Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2013.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Jane Eyre, Project Gutenberg [non-primary source needed]

- ^ Michael Inwood (9 February 2018). Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit: Translated with introduction and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 432ff. ISBN 978-0-19-253458-3.

- ^ Ludwig Siep (16 January 2014). Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. Cambridge University Press. pp. 142ff. ISBN 978-1-107-02235-5.

- ^ Newmark, Peter (1998). "Friedrich von Schiller (1759–1805)". In Classe, O. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1238–1239. ISBN 978-1-884964-36-7.

- ^ Berge, Emma (2010). "The Robbers". The British Theatre Guide.

- ^ van den Berg, Klaus (2009). "The Royal Robe with Folds: Translatability in Schiller's The Robbers" (PDF). The Mercurian: A Theatrical Translation Review. 2 (2).

- ^ Billington, Michael (29 January 2005). "The German Shakespeare:Schiller used to be box-office poison. Why are his plays suddenly back in favour, asks Michael Billington". The Guardian.

- ^ Schönfeld, Christiane; Rasche, Hermann, eds. (2007). Processes of Transposition: German Literature and Film. Rodopi. p. 23. ISBN 9789042022843.

- ^ "Giselher Klebe – Räuber – Opera". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Otto Erich Deutsch et al. Schubert Thematic Catalogue. German version, 1978 (Bärenreiter), p. 133

External links

[edit] Media related to The Robbers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Robbers at Wikimedia Commons- The Robbers at Project Gutenberg

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Die Räuber

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Die Räuber Works related to The Robbers at Wikisource

Works related to The Robbers at Wikisource

KSF

KSF