The Turn of the Screw

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 24 min

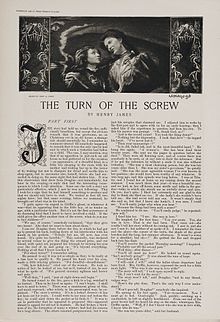

First page of the 12-part serialisation of The Turn of the Screw in Collier's Weekly (January 27 – April 16, 1898) | |

| Author | Henry James |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | The Macmillan Company (New York City) William Heinemann (London) |

Publication date | January 27 – April 16, 1898 (serial) October 7, 1898 (book) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| OCLC | 40043490 |

| LC Class | PS2116 .T8 1998 |

| Text | The Turn of the Screw at Wikisource |

The Turn of the Screw is an 1898 gothic horror novella by Henry James which first appeared in serial format in Collier's Weekly from January 27 to April 16, 1898. On October 7, 1898, it was collected in The Two Magics, published by Macmillan in New York City and Heinemann in London. The novella follows a governess who, caring for two children at a remote country house, becomes convinced that they are haunted. The Turn of the Screw is considered a work of both Gothic and horror fiction.

In the century following its publication, critical analysis of the novella underwent several major transformations. Initial reviews regarded it only as a frightening ghost story, but, in the 1930s, some critics suggested that the supernatural elements were figments of the governess' imagination. In the early 1970s, the influence of structuralism resulted in an acknowledgement that the text's ambiguity was its key feature. Later approaches incorporated Marxist and feminist thinking, though the validity of these later approaches is disputed.

The novella has been adapted several times, including a Broadway play (1950), a chamber opera (1954), two films (in 1961 and 2020), and a miniseries (2020).

Plot

[edit]On Christmas Eve, an unnamed narrator and some of his friends are gathered around a fire. One of them, Douglas, reads a manuscript written by his sister's late governess. The manuscript tells the story of her being hired by a man who has become responsible for his young niece and nephew following the deaths of their parents. He lives mainly in London and has a country house in Bly, Essex.

The boy, Miles, is attending a boarding school, while his younger sister, Flora, is living in Bly, where she is cared for by Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper. Flora's uncle, the governess's new employer, is uninterested in raising the children and gives her full charge, explicitly stating that she is not to bother him with communications of any sort. The governess travels to Bly and begins her duties.

Miles returns from school for the summer just after a letter arrives from the headmaster, informing his caretakers that he has been expelled. Miles never speaks of the matter, and the governess is hesitant to raise the issue. She fears there is some horrible secret behind the expulsion, but is too charmed by the boy to want to press the issue.

Soon after, around the grounds of the estate, the governess begins to see the figures of a man and woman whom she does not recognize. The figures come and go at will without being seen or challenged by other members of the household, and they seem to the governess to be supernatural. She learns from Mrs. Grose that the governess's predecessor, Miss Jessel, and another employee, Peter Quint, had had a close relationship. Before their deaths, Jessel and Quint spent much of their time with Flora and Miles, and the governess becomes convinced that the two children are aware of the ghosts' presence and influenced by them.

Without permission, Flora leaves the house while Miles is playing music for the governess. The governess notices Flora's absence and goes with Mrs. Grose in search of her. They find her on the shore of a nearby lake, and the governess is convinced that Flora has been talking to the ghost of Miss Jessel. The governess sees Miss Jessel and believes Flora sees her as well, but Mrs. Grose does not. Flora denies seeing Miss Jessel and begins to insist that she will not see the new governess again.

The governess decides that Mrs. Grose should take Flora away to her uncle in attempt to escape Miss Jessel's influence. Left alone with the governess, Miles at last confesses he was expelled for something he said but cannot remember what he said or to whom he said it. The ghost of Quint appears to the governess at the window. The governess shields Miles, who attempts to see the ghost. The governess insists to Miles he is no longer controlled by the ghost, only to find that Miles has died in her arms.

Genre

[edit]

Gothic fiction

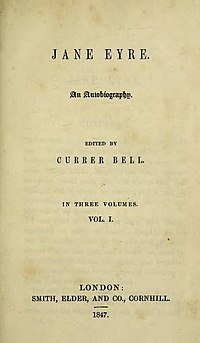

[edit]As a piece of Gothic fiction, critics highlight the influence of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847) on the novella. The Turn of the Screw borrows both from Jane Eyre's themes of class and gender,[1] and from its mid-nineteenth century setting.[2] The novella alludes to Jane Eyre in tandem with an explicit reference to Ann Radcliffe's Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), wherein the governess wonders if there might be a secret relative hidden in the attic at Bly.[3] One critic writes that the only "definite event" in the novel that does not "belong" in Gothic fantasy is Miles' expulsion from school.[4]

Although the influence of the Gothic on the novella is clear, it cannot only be characterised as one. James' ghosts differ from those of traditional Gothic tales – frightening, often bound in chains – by appearing like their living selves.[5] Similarly, the novella foregoes major devices associated with Gothic novels, such as digressions, as in Frankenstein (1818) and Dracula (1897), instead relating one whole, continuous narrative.[6]

Ghost story and horror fiction

[edit]For the story's publication in Collier's Weekly, James was contracted to write a ghost story.[7] As a result, some critics have regarded it in that tradition. L. Andrew Cooper observed that The Turn of the Screw might be the best-known example of a ghost story which exploits the ambiguity of a first-person narrative.[8] Citing James' reference to the work as his "designed horror", Donald P. Costello suggested that the effect of a given scene varies depending on who represents the action. In scenes where the governess directly reports on what she sees, the effect is horror, but in those where she merely comments, the effect is "mystification".[9] In his 1983 nonfiction survey of the horror genre, author Stephen King described The Turn of the Screw and The Haunting of Hill House (1959) as the only two great supernatural works of horror in a century. He argued that both contain "secrets best left untold and things left best unsaid", calling that the basis of the horror genre.[10] Gillian Flynn called the novella one of the most chilling ghost stories ever written.[11]

Several biographers have indicated that James was familiar with spiritualism, and at the very least regarded it as entertainment. His brother William was an active researcher of supernatural phenomena.[12] Scientific inquiry at the time was curious about the existence of ghosts, and James' description of Peter Quint and Miss Jessel—dressed in black with severe expressions—resemble the ghosts found in scientific literature rather than those of fictional narratives.[13] The character of Douglas describes himself as a student of Trinity College, where James knew research into the supernatural occurred. It is unknown whether James believed in ghosts.[14][a]

Background

[edit]Biographical context and composition

[edit]By the 1890s, James' readership had dwindled since the success of Daisy Miller (1878), and he had encountered financial troubles. His health had also worsened, with advancing gout,[15] and several of his close friends had died: his sister and diarist Alice James, and writers Robert Louis Stevenson and Constance Fenimore Woolson.[16] In a letter from October 1895, James wrote: "I see ghosts everywhere".[17] In an entry in his journal from January 12, 1895, James recounts a ghost story told to him by Edward White Benson, the archbishop of Canterbury, while visiting him for tea at his home two days earlier. The story bears a striking resemblance to what would eventually become The Turn of the Screw, with depraved servants corrupting young children before and after their deaths.[18]

Towards the end of 1897, James was contracted to write a twelve-part ghost story for Collier's Weekly, an illustrated magazine. Having just signed a twenty-one year lease on a house in Rye, East Sussex, James —thankful for the additional income—accepted the offer.[19][20] Collier's Weekly paid James US$900 (equivalent to US$27,659 in 2019) for the serial rights.[21] A year earlier, in 1897, The Chap-Book paid him US$150 (equivalent to US$4,610 in 2019) for serial and book rights to What Maisie Knew.[22]

James found it difficult to write by hand,[23] reserving that for his journals. The Turn of the Screw was dictated to his secretary, William MacAlpine, who took shorthand notes and returned with typed notes the following day. Finding such a delay frustrating, James purchased his own Remington typewriter and dictated directly to MacAlpine.[24][25] In December 1897, James wrote to his sister-in-law: "I have, at last, finished my little book."[26]

Publication and later revisions

[edit]The Turn of the Screw was first published in the magazine Collier's Weekly, serialised in 12 installments (27 January – 16 April 1898). The title illustration by John La Farge depicts the governess with her arm around Miles. Episode illustrations were by Eric Pape.[27]

-

"The next night, by the corner of the hearth, in the best chair … Douglas began to read"

-

"He did stand there!—But high up, beyond the lawn and at the very top of the tower"

-

"Holding my candle high, till I came within sight of the tall window"

-

"He presently produced something that made me drop straight down on the stone slab"

-

"I must have thrown myself, on my face, on the ground"

In October 1898, the novella appeared with the short story "Covering End" in a volume titled The Two Magics, published by Macmillan in New York City and by Heinemann in London.[28]

Ten years after publication, James revised The Turn of the Screw for the New York Edition of the text.[29] James made many changes, but most were minor, such as changing "utter" to "express"; the narrative was unchanged. The New York Edition's most important contribution was the retrospective account of the influences and writing of the novella James gave in his preface. James indicated, for example, that he was aware of research into the supernatural.[30] In his preface, James only briefly mentions the story's origin in a magazine. In 2016, Kirsten MacLeod, citing James' private correspondence, indicated that he had a strong dislike for the serial form.[31]

Reception

[edit]Early criticism

[edit]The horror of the story comes from the force with which it makes us realize the power that our minds possess for such excursions into the darkness; when certain lights sink or certain barriers are lowered, the ghosts of the mind, untraced desires, indistinct intimations, are seen to be a large company.

— Virginia Woolf, "The Supernatural in Fiction" (1918)[32][b]

Early reviews emphasised the novella's power to frighten, and most saw the tale as a brilliant, if simple, ghost story.[33] According to scholar Terry Heller, most early reviewers saw the novel as a formidable piece of Gothic fiction.[34]

An early review of The Turn of the Screw was in The New York Times Saturday Review of Books and Art, stating it was worthy of being compared to Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). The reviewer noted it as a successful study of evil, referring to the ghosts' influence over the children and the governess.[35] Scholar Terry Heller notes that the children featured prominently in early criticism because the novella violated a Victorian presumption of childhood innocence.[36]

Conceptions of the text wherein the ghosts are real entities are often referred to as the "apparitionist interpretation";[37] consequently, a "non-apparitionist" holds the opposite perspective.[38] In a 1918 essay, Virginia Woolf wrote that Miss Jessel and Peter Quint possessed "neither the substance nor independent existence of ghosts".[39] Woolf did not suggest that the ghosts were hallucinations, but—in a similar fashion to other early critics—said they represented the governess' growing awareness of evil in the world. The power of the story, she argued, was in forcing readers to realise the dark places fiction could take their minds.[40]

Psychoanalytic interpretations

[edit]In 1934, literary critic Edmund Wilson posited that the ghosts were hallucinations of the governess, who he suggested was sexually repressed. As evidence, Wilson points to her background as the daughter of a country parson, and suggests that she is infatuated with her employer.[41] Before Wilson's article, another critic—Edna Kenton—had written to similar effect, but Wilson's fame as a literary critic shifted the discourse around the novella completely.[42][43][c] Wilson drew heavily from Kenton's writing, but applied explicitly Freudian terminology.[44] For example, he pointed to Quint first being sighted by the governess on a phallic tower.[45] A book-length close reading of the text was produced in 1965 using Wilson's Freudian analysis as a foundation; it characterised the governess as increasingly mad and hysterical.[46] Leon Edel, James' most influential biographer, wrote that it is not the ghosts who haunt the children, but the governess.[47]

While many supported Wilson's theory, it was by no means authoritative.[48] Robert B. Heilman was a prominent advocate for the apparitionist interpretation; he saw the story as a Hawthornesque allegory about good and evil, and the ghosts as active agents to that effect.[49] Scholars critical of Wilson's essay pointed to Douglas' positive account of the governess's character in the prologue, long after her death. Most crucially, they indicated that the governess's description of the ghost enabled Mrs Grose to identify him as Peter Quint before the governess knew he existed.[49] The second point led Wilson to "retract his thesis (temporarily)";[48] in a later revision of his essay, he argued the governess had been made aware of another male at Bly by Mrs Grose.[50][d]

Structuralism

[edit]In the 1970s, critics began to apply structuralist Tzvetan Todorov's notion of the fantastic to The Turn of the Screw.[51][52] Todorov emphasised the importance of "hesitation" in stories with supernatural elements, and critics found an abundance of them within James' novella. For example, the reader's sympathy may hesitate between the children or the governess,[53] and the text hesitates between supporting the ghosts' existence, and rejecting them.[54] Christine Brooke-Rose argued in a three-part essay that the ambiguity so frequently argued over was a foundational part of the text that had been ignored.[55] From the 1980s onwards, critics increasingly refused to ask questions about diegetic elements of the text, instead acknowledging that many elements simply cannot be known definitively.[56]

Focus shifted away from whether the ghosts were real and onto how James generated and then sustained the text's ambiguity. A study into revisions James made to two paragraphs in the novella concluded that James was not striving for clarity, but to create a text which could not be interpreted definitively in either direction.[57]

This is still a position held by many critics, such as Giovanni Bottiroli, who argues that evidence for the intended ambiguity of the text can be found at the beginning of the novella, where Douglas tells his fictional audience that the governess had never told anyone but himself about the events that happened at Bly, and that they "would easily judge" why. Bottiroli believes that this address to Douglas' fictional audience is also meant as an address to the reader, telling them that they will "easily judge" whether or not the ghosts are real.[58]

Marxist and feminist approaches

[edit]After the debate over the reality of the ghosts quieted in literary criticism, critics began to apply other theoretical frameworks to The Turn of the Screw. Marxist critics argued that the emphasis placed by academics on James' language distracted from class-based explorations of the text.[59] The children's uncle, who featured largely only in the psychoanalytic interpretations as an obsession of the governess, was regarded by some as symbolising a selfish upper-class. Heath Moon notes how he abandoned his orphaned niece, nephew, and their ancestral home to instead live in London as a bachelor.[60] Mrs Grose's distaste for the relationship between Quint and Miss Jessel was noted to be part of a Victorian dislike for relationships that were between different social classes.[61] The death of Miles and Flora's parents in India became a fixture of postcolonial explorations of the text, given the status of India as a British colony during James' lifetime.[62]

Explorations of the governess have become a mainstay of feminist writing on the text. Priscilla Walton noted that James' account of the story's origin disparaged the ability of women to tell stories, and framed The Turn of the Screw as James thus telling it on their behalf.[63] Others see James in a more positive light. Paula Marantz Cohen positively compares James' treatment of the governess to Sigmund Freud's writing about a young woman named Dora. Cohen likens the way that Freud transforms Dora into merely a summary of her symptoms to how critics such as Edmund Wilson reduced the governess to a case of neurotic sexual repression.[64]

Adaptations

[edit]

The Turn of the Screw has been the subject of a range of adaptations and reworkings in a variety of media. Many of these have, themselves, been analysed in the academic literature on Henry James and neo-Victorian culture.[65]

Stage

[edit]The novella was adapted to an opera by Benjamin Britten, which premiered in 1954,[65] and the opera has been filmed on multiple occasions.[66] The novella was adapted as a ballet score (1980) by Luigi Zaninelli,[67] and separately as a ballet (1999) by Will Tucket for the Royal Ballet.[68] Harold Pinter directed The Innocents (1950), a Broadway play which was an adaptation of The Turn of the Screw.[69] An adaptation by Jeffrey Hatcher, using the title The Turn of the Screw, premiered in Portland, Maine, in 1996 and was produced off-Broadway in 1999.[70] Another adaptation of the same title by Rebecca Lenkiewicz was presented in a co-production with Hammer at the Almeida Theatre, London, in January 2013.[71]

Films

[edit]There have been numerous film adaptations of the novel.[67] The critically acclaimed The Innocents (1961), directed by Jack Clayton, and Michael Winner's prequel The Nightcomers (1972) are two notable examples.[65] Other feature film adaptations include Rusty Lemorande's 1992 eponymous adaptation (set in the 1960s);[72] Eloy de la Iglesia's Spanish language Otra vuelta de tuerca (The Turn of the Screw, 1985);[67] Presence of Mind (1999), directed by Atoni Aloy; and In a Dark Place (2006), directed by Donato Rotunno.[66] The Others (2001) is not an adaptation but has some themes in common with James's novella.[66][73] In 2018, director Floria Sigismondi filmed an adaptation of the novella, titled The Turning, on the Kilruddery Estate in Ireland.[74]

Television films have included a 1959 American adaptation as part of Ford Startime directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Ingrid Bergman;[66][75] the West German Die sündigen Engel (The Sinful Angel, 1962),[76] a 1974 adaptation directed by Dan Curtis, adapted by William F. Nolan;[66] a French adaptation entitled Le Tour d'écrou (The Turn of the Screw, 1974); a 1982 adaptation directed by Petr Weigl primarily starring Czech actors lip-synching;[77] a 1990 adaptation directed by Graeme Clifford; The Haunting of Helen Walker (1995), directed by Tom McLoughlin; a 1999 adaptation directed by Ben Bolt;[66] a low-budget 2003 version written and directed by Nick Millard; the Italian-language Il mistero del lago (The Mystery of the Lake, 2009); and a 2009 BBC film adapted by Sandy Welch, starring Michelle Dockery, Dan Stevens and Sue Johnston.[76] A Brazilian movie named Através da Sombra (Through the Shadow, 2015) was released, heavily influenced by the book, only changing the characters' names and location to make it feel like it is set in Brazil.[78]

Literature

[edit]Literary references to and influences by The Turn of the Screw identified by the James scholar Adeline R. Tintner include The Secret Garden (1911), by Frances Hodgson Burnett; "Poor Girl" (1951), by Elizabeth Taylor; The Peacock Spring (1975), by Rumer Godden; Ghost Story (1975) by Peter Straub; "The Accursed Inhabitants of House Bly" (1994) by Joyce Carol Oates; and Miles and Flora (1997)—a sequel—by Hilary Bailey.[79] Further literary adaptations identified by other authors include Affinity (1999), by Sarah Waters; A Jealous Ghost (2005), by A. N. Wilson;[80] Florence & Giles (2010), by John Harding;[65] and Maybe This Time (2010) by Jennifer Crusie.[81] Young adult novels inspired by The Turn of the Screw include The Turning (2012) by Francine Prose[82] and Tighter (2011) by Adele Griffin.[83] Ruth Ware's 2019 novel The Turn of the Key sets the story in the 21st century.[84]

Television

[edit]The Turn of the Screw has also influenced television.[85] In December 1968, the ABC daytime drama Dark Shadows featured a storyline based on The Turn of the Screw. In the story, the ghosts of Quentin Collins and Beth Chavez haunted the west wing of Collinwood, possessing the two children living in the mansion. The story led to a year-long story in the year 1897, as Barnabas Collins travelled back in time to prevent Quentin's death and stop the possession.[85] In early episodes of Star Trek: Voyager ("Cathexis", "Learning Curve" and "Persistence of Vision"), Captain Kathryn Janeway is seen on the holodeck acting out scenes from the holonovel Janeway Lambda one, which appears to be based on The Turn of the Screw.[86] The novel was adapted as a Mexican miniseries entitled Otra vuelta de tuerca (The Turn of the Screw) in 1981,[76] and in 2020, Netflix adapted the novella as The Haunting of Bly Manor for the second season of Mike Flanagan's The Haunting anthology series.[87][88]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ According to Beidler, noted psychical researchers Arthur and Gerald Balfour, Frederic and Arthur Myers, and William James all attended Trinity College, and James attended at least one lecture by their Society for Psychical Research in place of the absent William.[14]

- ^ This essay is only available in Granite and Rainbow, which was edited by Woolf's husband and published over a decade after her death.

- ^ Wilson begins his article by acknowledging Kenton's influence.

- ^ Not to be confused with Wilson's second revision, with a near-identical reference, except published in 1959 by Oxford University Press.

References

[edit]- ^ Bell, Millicent (1993). "Class, Sex, and the Victorian Governess". In Pollak, Vivian R. (ed.). New Essays on Daisy Miller and The Turn of the Screw. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 100.

- ^ Kauffman, Linda (1986). Discourses of Desire: Gender, Genre, and Epistolary Fictions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 212.

- ^ Davidson, Guy (2011). ""Almost a Sense of Property": Henry James's "The Turn of the Screw", Modernism, and Commodity Culture". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 53 (4): 455–478. doi:10.1353/tsl.2011.0017. ISSN 0040-4691. JSTOR 41349144. S2CID 31268812. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Pittock, Malcolm (1 October 2005). "The Decadence of The Turn of the Screw". Essays in Criticism. 55 (4): 332–351. doi:10.1093/escrit/cgi025. ISSN 1471-6852. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Kirby, David (1991). The Portrait of a Lady and The Turn of the Screw. London: Macmillan Education UK. p. 72. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21424-2. ISBN 978-0-333-49238-3. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Schleifer, Ronald (1980). "The Trap of the Imagination: The Gothic Tradition, Fiction, and "The Turn of the Screw"". Criticism. 22 (4): 297–319. ISSN 0011-1589. JSTOR 23105143. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Reed, Kimberly C. (2008). ""The Abysses of Silence" in The Turn of the Screw". In Zacharias, Greg W. (ed.). A Companion to Henry James. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 102.

- ^ Cooper, L. Andrew (2010). Gothic Realities: The Impact of Horror Fiction on Modern Culture. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7864-5788-5. OCLC 652654384. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Costello, Donald P. (1960). "The Structure of The Turn of the Screw". Modern Language Notes. 75 (4): 312–321. doi:10.2307/3040418. ISSN 0149-6611. JSTOR 3040418. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ King, Stephen (1983). Danse Macabre. Berkley: Berkley Books. p. 50. ISBN 9780425064627.

- ^ Flynn, Gillian (18 May 2016). "Gillian Flynn on Emma Thompson Reading The Turn of the Screw". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Krister Dylan Knapp, William James: Psychical Research and the Challenge of Modernity (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), pp. 28-31.

- ^ Kirby, David (1991). The Portrait of a Lady and The Turn of the Screw. London: Macmillan Education UK. p. 72. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21424-2. ISBN 978-0-333-49238-3.

- ^ a b Beidler 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Beidler, Peter G. (1995). The Turn of the Screw: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: St. Martin's Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-312-08083-9.

- ^ Reed 2008, p. 101.

- ^ James, Henry (1999). Warren, Deborah; Warren, Jonathan (eds.). The Turn of the Screw (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 102. ISBN 9780393959048.

- ^ Matthiessen, F. O.; Murdock, Kenneth B., eds. (1955). The Notebooks of Henry James. New York: Braziller. pp. 178–179.

- ^ Reed 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Beidler 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Anesko, Michael (1986). Henry James and the Profession of Authorship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 193.

- ^ Kramer, Sidney (1940). History of Stone and Kimball and Herbert S. Stone and Company: With a Bibliography of Their Publications, 1893–1905. Chicago: Chicago: Norman W. Forgue. pp. 270–272.

- ^ Beidler 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Novick, Sheldon M. (2007). Henry James: The Mature Master. New York: Random House. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-307-79774-2.

- ^ Thurschwell, Pamela (1 March 1999). "Henry James and Theodora Bosanquet: On the typewriter, In the Cage, at the Ouija board". Textual Practice. 13 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/09502369908582327. ISSN 0950-236X.

- ^ Edel, Leon (1985). Henry James: A Life. New York: Harper. pp. 462–463.

- ^ Orr, Leonard (2009). James's The Turn of the Screw. London: A&C Black. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8264-2432-7.

- ^ James, Henry (1996). Complete Stories, 1892–1898. New York: Library of America. p. 941. ISBN 978-1-883011-09-3.

- ^ Orr 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Roellinger, Francis X. (1949). "Psychical Research and The Turn of the Screw". American Literature. 20 (3): 401–412. doi:10.2307/2921600. JSTOR 2921600.

- ^ MacLeod, Kirsten (1 November 2018). "Material Turns of the Screw: The Collier's Weekly Serialization of The Turn of the Screw (1898)". Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens. 84 (84): 9–10. doi:10.4000/cve.2986. ISSN 0220-5610. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1958). "The Supernatural in Fiction". Granite and Rainbow. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. p. 63.

- ^ Beidler 1995, p. 130.

- ^ Heller 1989, pp. 9–10.

- ^ "The Turn of the Screw: Review". The New York Times Saturday Review of Books and Art. 5 October 1898. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Heller 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Bontly, Thomas J. (1969). ""Henry James's 'General Vision of Evil' in The Turn of the Screw"". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 9 (4): 721–735. doi:10.2307/450043. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 450043.

- ^ Killoran, Helen (1993). "The Governess, Mrs. Grose and "The Poison of an Influence" in "The Turn of the Screw"". Modern Language Studies. 23 (2): 13–24. doi:10.2307/3195031. ISSN 0047-7729. JSTOR 3195031.

- ^ Woolf 1958, p. 62-63.

- ^ Woolf 1958, p. 63.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (April 1934). "The Ambiguity of Henry James". Hound and Horn: 385–406.

- ^ Lind, Sydney E. (1970). "'The Turn of the Screw': The Torment of Critics". Centennial Review. 4: 225–240.

- ^ Cargill, Oscar (1956). "Henry James as Freudian Pioneer". Chicago Review. 10 (2): 13–29. doi:10.2307/25293218. JSTOR 25293218.

Until Edmund Wilson designated The Turn of the Screw a study in psychopathology, only three persons had had the temerity to guess that it was something more than a ghost story.

- ^ Heilman, Robert B. (November 1947). "The Freudian Reading of The Turn of the Screw". Modern Language Notes. 62 (7): 433–455. doi:10.2307/2909426. JSTOR 2909426.

Wilson provides the scholarly foundation for the airy castle of Miss Kenton's intuitions.

- ^ Kirby, David (1991). The Portrait of A Lady and The Turn of the Screw: Henry James and Melodrama. London: Macmillan Education. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-333-49238-3.

- ^ Beidler 1995, p. 131.

- ^ Edel, Leon (1969). Henry James: The Treacherous Years, 1895-1901. London: Hart-Davis. pp. 191–203.

- ^ a b Reed 2008, p. 103.

- ^ a b Beidler 1995, p. 133.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund (1938). "The Ambiguities of Henry James, revised". The Triple Thinkers. Harcourt, Brace, and Co.: 122–164.

- ^ Kirby, David (1991). The Portrait of A Lady and The Turn of the Screw: Henry James and Melodrama. London: Macmillan Education. pp. 78–81. ISBN 978-0-333-49238-3.

- ^ Beidler 1995, p. 134-137.

- ^ Siebers, Tobin (1983). "Hesitation, History, and Reading: Henry James' The Turn of the Screw". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 25: 559–573.

- ^ Heller, Terry (1989). The Turn of the Screw: Bewildered Visions. Massachusetts: Twayne's Publishers. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Brooke-Rose, Christine (1976). "The Squirm of the True, II: A Structural Analysis of Henry James' The Turn of the Screw". PTL: A Journal for Descriptive Poetics and Theory of Literature. 1: 513–46.

- ^ Rowe, John Carlos (1984). "Psychoanalytical Significances: The Use and Abuse of Uncertainty in The Turn of the Screw". The Theoretical Dimensions of Henry James. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 144.

- ^ Macleod, Norman (1988). "Stylistics and the Ghost Story: Punctuation, Revisions, and Meaning in The Turn of the Screw". In Anderson, John M.; Macleod, Norman (eds.). Edinburgh Studies in the English Language. Edinburgh: John Donald. pp. 133–55.

- ^ Bottiroli, Giovanni (15 December 2019). "The Turn of the Screw. A tale that "turns"". Enthymema (24): 43–58. doi:10.13130/2037-2426/12584. ISSN 2037-2426. S2CID 213522030.

- ^ Kirby, David (1991). The Portrait of A Lady and The Turn of the Screw: Henry James and Melodrama. London: Macmillan Education. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-333-49238-3.

- ^ Moon, Heath (1982). "More Royalist than the King: The Governess, the Telegraphist, and Mrs Gracedew". Criticism. 24: 16–35.

- ^ Nardin, Jane (1978). "The Turn of the Screw: The Victorian Background". Mosaic. 12 (1): 131–142.

- ^ McMaster, Graham (1988). "Henry James and India: A Historical Reading of The Turn of the Screw". Clio. 18: 23–40.

- ^ Walton, Priscilla L. " 'What then on earth was I?": Feminine Subjectivity and The Turn of the Screw", in Beidler 1995, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Cohen, Paula Marantz (Winter 1986). "Freud's Dora and James's Turn of the Screw: Two Treatments of the Female 'Case'". Criticism. 28 (1). Wayne State University Press: 73–87. ISSN 0011-1589. JSTOR 23110359.

- ^ a b c d Dinter, Sandra (2012). "The mad child in the attic: John Harding's Florence & Giles as a neo-victorian reworking of The Turn of the Screw". Neo-Victorian Studies. 5 (1): 60–88.

- ^ a b c d e f Haralson & Johnson 2009, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Brown, Monika (1998). "Film Music as Sister Art: Adaptations of 'The Turn of the Screw.'". Mosaic (Winnipeg). 31 (1).

- ^ Jays, David (July 1, 2006). "Ballet – From page to stage[permanent dead link]". Financial Times. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Baker, William (2008). Harold Pinter. A&C Black. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8264-9970-7.

- ^ Kabatchnik, Amnon (2012). Blood on the Stage, 1975-2000: Milestone Plays of Crime, Mystery, and Detection. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 466–473. ISBN 978-0-8108-8354-3.

- ^ Masters, Tim (23 November 2012). "Hammer takes first steps on stage in Turn of the Screw". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ Haralson, Eric L.; Johnson, Kendall (2009). Critical companion to Henry James: a literary reference to his life and work. New York: Facts On File. p. 293. ISBN 978-1-4381-1727-0. OCLC 466089734.

- ^ Skidelsky, William (30 May 2010). "Classics corner: The Turn of the Screw". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Finn, Melanie (21 February 2018). "Steven Spielberg chooses Ireland as backdrop to new horror film". The Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Koch, J. Sarah (2002). "A Henry James Filmography". In Griffin, Susan M. (ed.). Henry James Goes to the Movies. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 335–358. ISBN 978-0-8131-3324-9.

- ^ a b c Hischak, Thomas S. (2012). American Literature on Stage and Screen: 525 Works and Their Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 253. ISBN 9780786492794.

- ^ Holland, J. (2006). "Turn of the Screw (review)". Notes. 62 (3): 784–785. doi:10.1353/not.2006.0020. S2CID 191511837.

- ^ Oricchio, Luiz Zanin (15 November 2016). "Através da Sombra, de Walter Lima Jr., revela-se um suspense de qualidade". O Estado de S. Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ Tintner, Adeline R. (1998). Henry James's legacy : the afterlife of his figure and fiction. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 371–382. ISBN 0-8071-2157-6. OCLC 37864534.

- ^ de Aramburú, Arias; Pulham, Patricia, eds. (2009). "The Haunting of Henry James: Jealous Ghosts, Affinities and The Others". Haunting and spectrality in neo-Victorian fiction: possessing the past. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 111–130. ISBN 978-0-230-24674-4. OCLC 608021992.

- ^ "Maximum Shelf: Maybe This Time". Shelf Awareness. 21 July 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "The Turning by Francine Prose". Kirkus. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Tighter by Adele Griffin". Kirkus. 15 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Book Review: The Turn of the Key by Ruth Ware", Crime by the Book, 13 August 2019

- ^ a b Sborgi, Anna Viola (2011). "To think and watch the Evil: The Turn of the Screw as cultural reference in television from Dark Shadows to C.S.I.". Babel: Littératures Plurielles. 24 (24): 181–94 (see paragraph 8). doi:10.4000/babel.184. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Ruditis, Paul (2003). Star Trek Voyager Companion. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-743-41751-8.

- ^ Barsanti, Sam (21 February 2019). "The Haunting Of Hill House is taking on The Turn Of The Screw for its second season". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Whalen, Andrew (21 February 2019). "'The Haunting of Hill House' Season 2 Based on Sexually Ambiguous Book, Terrifying True Story". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

External links

[edit]- The Turn of the Screw at Standard Ebooks

- The Turn of the Screw at Project Gutenberg (1898 book version)

The Turn of the Screw public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Turn of the Screw public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Author's preface to the New York Edition text of The Turn of the Screw (1908) Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The Turn of the Screw / 1992 film adaptation at IMDb

KSF

KSF