The Women (1939 film)

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 16 min

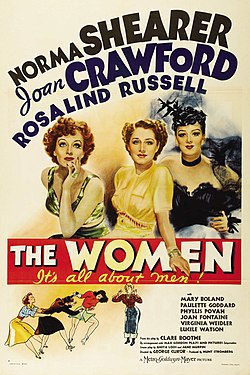

| The Women | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Cukor |

| Screenplay by | Anita Loos Jane Murfin |

| Based on | The Women 1936 play by Clare Boothe Luce |

| Produced by | Hunt Stromberg |

| Starring | Norma Shearer Joan Crawford Rosalind Russell |

| Cinematography | Joseph Ruttenberg Oliver T. Marsh |

| Edited by | Robert J. Kern |

| Music by | David Snell Edward Ward |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 133 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | English Italian |

| Budget | $1,688,000[1] |

| Box office | $2,270,000[1] |

The Women is a 1939 American comedy-drama film directed by George Cukor. The film is based on Clare Boothe Luce's 1936 play of the same name, and was adapted for the screen by Anita Loos and Jane Murfin, who had to make the film acceptable for the Production Code for it to be released.

The film stars Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard, Joan Fontaine, Lucile Watson, Mary Boland, Florence Nash, and Virginia Grey. Marjorie Main and Phyllis Povah also appear, reprising their stage roles from the play. Ruth Hussey, Virginia Weidler, Butterfly McQueen, Theresa Harris, and Hedda Hopper also appear in smaller roles. Fontaine was the last surviving actress with a credited role in the film; she died in 2013.

The film continued the play's all-female tradition—the entire cast of more than 130 speaking roles was female. Set in the glamorous Manhattan apartments of high society evoked by Cedric Gibbons, and in Reno, Nevada, where they obtain their divorces, it presents an acidic commentary on the pampered lives and power struggles of various rich, bored wives and other women they come into contact with.

Filmed in black and white, it includes a six-minute fashion parade filmed in three-strip Technicolor, featuring Adrian's most outré designs; often cut in modern screenings, it has been restored by Turner Classic Movies. On DVD, the original black-and-white fashion show, which is a different take, is available for the first time.

Throughout The Women, not a single male character is seen or heard. The attention to detail was such that even in props such as portraits, only female figures are represented, and several animals which appeared as pets were also female. The only exceptions are a poster-drawing of a bull in the fashion show segment, a framed portrait of Stephen Haines as a boy, a figurine on Mary's night stand, and an advertisement on the back of the magazine Peggy reads at Mary's house before lunch that contains a photograph of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

In 2007, The Women was included in the annual selection of 25 motion pictures added to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" and recommended for preservation.[2]

Plot

[edit]The film focuses on the lives and relationships of a group of Manhattan women and the scores of women who work for them. It centers on Mary Haines, the cheerful, contented wife of Stephen, her daughter Mary, and her circle of "friends". Mary's cousin Sylvia Fowler goes to Sydney's elite salon to get the latest nail color: Jungle Red. Olga, the manicurist, reveals that Mary's husband has been "stepping out" with a predatory perfume counter girl named Crystal Allen. Sylvia eagerly shares the news with Mary's friends and sets Mary up with Olga.

Mary is shattered to learn about Stephen's infidelity. Her mother urges patience and takes Mary to Bermuda with her, so she can take time to think. When they return, Mary goes to a couturier for a fitting. Crystal appears, ordering expensive clothes. Stephen is now keeping her. At Sylvia's insistence, Mary confronts Crystal, who suggests that Mary keep the status quo unless she wants to lose Stephen in a divorce. Heartbroken and humiliated, Mary leaves. The gossip continues, exacerbated by Sylvia and their friend Edith, who turns the affair into a public scandal by recounting Sylvia's version of the story to a gossip columnist. Mary decides to divorce her husband despite his efforts to make her stay. As she packs to leave for Reno, Mary explains the divorce to Little Mary, who weeps alone in the bathroom.

On the train to Reno, Mary meets three women with the same destination and purpose: the dramatic, extravagant Countess de Lave; Miriam Aarons, a tough-cookie chorus girl; and, to her surprise, her shy young friend Peggy Day, who has been pushed into divorce by Sylvia. They all settle in at a Reno ranch, where they get plenty of commonsense advice from Lucy, the gruff, warm-hearted woman who runs the ranch. The Countess tells tales of her multiple husbands and seems to have found another prospect in a cowboy named Buck Winston. Miriam has been having an affair with Sylvia Fowler's husband and plans to marry him. Peggy discovers that she is pregnant, calls her husband, and happily plans to hurry home. Sylvia arrives at the ranch; Howard is suing her, thanks to recorded evidence of mental cruelty. When she discovers that Miriam is the next Mrs. Fowler, she attacks her, and a fight ensues.

Mary's divorce comes through, but Miriam tries to convince her that she should forget her pride and call Stephen. Before Mary can decide, Stephen calls to inform Mary that he and Crystal have just been married.

Two years later, Crystal, now Mrs. Haines, is taking a bubble bath and talking on the phone to her lover, Buck Winston, now a radio star and married to the Countess. Little Mary overhears the conversation before being shooed away by Crystal. Sylvia picks up the phone and hears the voice of Crystal's lover.

Mary hosts a dinner for her Reno buddies and her Manhattan friends—excepting Sylvia—celebrating Buck and the Countess's second anniversary. The Countess, Miriam, and Peggy urge Mary to come along to a nightclub, but she stays home. Little Mary inadvertently reveals how unhappy Stephen is and mentions Crystal's "lovey dovey" talk with Buck on the telephone. Mary is transformed, crying "I've had two years to grow claws, Mother—Jungle Red!"

In the nightclub's ladies' lounge, Mary worms the details out of Sylvia and gets the news to a gossip columnist (played by Hedda Hopper). Mary tells the Countess that her husband Buck has been having an affair with Crystal, then informs Crystal that everyone knows what she has been doing. Crystal does not care. Mary can have Stephen back, since she will now have Buck to support her. The weeping Countess reveals that she has been funding Buck's radio career and that without her, he will be penniless and jobless. Crystal resigns herself to the fact that she will be heading back to the perfume counter, adding: "And by the way, there's a name for you ladies, but it isn't used in high society—outside of a kennel." Mary, triumphant, heads out the door, arms wide open to receive Stephen.

Cast

[edit]- Norma Shearer as Mary Haines

- Joan Crawford as Crystal Allen

- Rosalind Russell as Sylvia Fowler

- Mary Boland as The Countess De Lave (Flora)

- Paulette Goddard as Miriam Aarons

- Phyllis Povah as Edith Potter

- Joan Fontaine as Peggy Day

- Virginia Weidler as Little Mary Haines

- Lucile Watson as Mrs. Morehead

- Marjorie Main as Lucy

- Virginia Grey as Pat

- Ruth Hussey as Miss Watson

- Muriel Hutchison as Jane

- Hedda Hopper as Dolly Dupuyster

- Florence Nash as Nancy Blake

- Cora Witherspoon as Mrs. Van Adams

- Ann Morriss as Exercise instructress

- Dennie Moore as Olga

- Mary Cecil as Maggie

- Mary Beth Hughes as Miss Trimmerback

- Lilian Bond as Mrs. Erskine

- Jane Isbell as Edith's daughter (uncredited)

- Mariska Aldrich as Singing Teacher (uncredited)

- Butterfly McQueen as Lulu (uncredited)

- Barbara Jo Allen as Receptionist (uncredited)

- Judith Allen as Corset Model (uncredited)

- Gertrude Astor as Nurse (uncredited)

- Marie Blake as Stockroom girl (uncredited)

- Suzanne Kaaren as Tamara (uncredited)

- Theresa Harris as Olive (uncredited)

- Esther Dale as Ingrid (uncredited)

- Betty Blythe as Mrs. South (uncredited)

- Barbara Pepper as Tough woman (uncredited)

- Mabel Colcord as Woman receiving massage (uncredited)

-

Norma Shearer

-

Joan Crawford

-

Rosalind Russell

-

Paulette Goddard

-

Joan Fontaine

-

Mary Boland

-

Virginia Weidler

-

Virginia Grey

-

Phyllis Povah

-

Lucille Watson

-

Marjorie Main

Production

[edit]

In January 1937, producers Harry M. Goetz and Max Gordon bought the film rights to the play for $125,000 and planned on turning it into a Claudette Colbert vehicle, with Gregory LaCava as the director.[3] In March 1938, Norma Shearer and Carole Lombard were in negotiations to star.[4] It was rumored that MGM sought to bring back Marion Davies for the role of Sylvia Fowler, but she declined. In November 1938, it was announced Jane Murfin was busy writing the film's screenplay at MGM. Virginia Weidler was cast on April 24, 1939.[5] F. Scott Fitzgerald worked on the script early on in the process, but was uncredited.[6] Cast member Florence Nash's sister Mary Nash had starred in a 1911 play called The Woman.

After the opening credits the film offers a preview of—and insight into—the principal characters with shots of animals that dissolve to shots of the women, with appropriate music. Mary is a doe, Crystal a panting leopard, Sylvia a snarling black cat, Flora a monkey, Miriam a vixen (female fox), Peggy a lamb, Mary's mother an owl, Edith a cow chewing its cud, Lucy a neighing horse. TCM.com incorrectly identifies the leopard as a lion and the fox as a wolf.[7] All of the animals in the picture are female.[7]

The New York Times reported on Cukor's strategies for managing a cast of 135 women led by three famously demanding stars. He described one technique for dealing with precedence: He made sure that all three stars were called to set simultaneously, either by sending separate staff to knock on their dressing room doors at the identical moment, or by calling "Ready ladies!" so all could hear. This system lapsed only once, and the offended star (not named) remained in her dressing room for a very long time.[8]

When it comes to bloopers, the film contains a fine example of misused stock footage. The film transitions from Little Mary weeping in the bathroom over the news of the divorce through an establishing shot—a night scene of a train speeding through a desert in the far West—to the compartment where Mary consoles a weeping Peggy. Peggy barely managed to catch the train for Reno. It is the first night out, and the train is nowhere near the West. The journey from New York to Reno took three full days at the time (and was no faster in 2013).[9] The same desert shot had been used appropriately three years before, in After the Thin Man, as Nick and Nora Charles near the end of their two-day trip to California.

Technicolor fashion show

[edit]The Women has one sequence in Technicolor, a fashion show. When interviewed by TCM host Robert Osborne, director George Cukor stated that he did not like the sequence and that he wanted to remove it from the film. New York Times critic Frank Nugent agreed with this assessment. In his September 22, 1939, review of the film, he reported that "a style show in Technicolor...may be lovely—at least that's what most of the women around us seemed to think—but has no place in the picture. Why not a diving exhibition or a number by the Rockettes? It is the only mark against George Cukor's otherwise shrewd and sentient direction."[10]

In 2018, British critic Peter Bradshaw describes the “remarkable” technicolor fashion show as “a mesmeric, wordless interlude that appears to allude to the nature of these women’s lives. It starts with jolly outdoor scenes, almost pastoral, but then descends into moody nightclub darkness, a world of metropolitan chic and brooding sensuality. I can only compare it to the nightmare in Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound.”[11]

Reception

[edit]The film was commercially successful and was cited as one of the best of the year.[12] Although it received no Academy Award nominations, many critics now describe it as one of the major films of what was a stellar year in Hollywood film production.

The New York Times critic Frank Nugent praised the film with characteristic wit:

"...(G)oing and coming to syrupy movies, we lose our sense of balance...Miss Boothe...has dipped her pen in venom. Metro, without alkalizing it too much, has fed it to a company of actresses who normally are so sweet that butter (as the man says) would not melt in their mouths. And, instead of gasping and clutching at their throats, the women—bless 'em—have downed it without blinking, have gone on a glorious cat-clawing rampage and have turned in one of the merriest pictures of the season...(Boothe's) sociological investigation of the scalpel-tongued Park Avenue set...is a ghoulish and disillusioning business, and the drama critics, when first they saw the play, turned away in chivalrous horror...Possibly some of that venom has been lost in the screen translation...The omissions are not terribly important, and some of the new sequences are so good Miss Boothe might have thought of them herself. ...The most heartening part of it all, though, aside from the pleasure we derive from hearing witty lines crackle on the screen, is the way Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard and the others have leaped at the chance to be vixens. ... even Miss Shearer's Mary sharpens her talons finally and joins the birds of prey...(in) one of the best performances she has given. Rosalind Russell, who usually is sympathetic as all-get-out, is flawless...as the archprowler in the Park Avenue jungle. (all the actors are) all so knowing, so keen on their jobs and so successful in bringing them off that we don't know when we've ever seen such a terrible collection of women. They're really appallingly good, and so is their picture."[13]

Leonard Maltin gave the film 3 1/2 out of 4 stars: "All-star (and all-female) cast shines in this hilarious adaptation of Clare Boothe play about divorce, cattiness, and competition in circle of "friends.'' Crawford has one of her best roles..."[14] Pauline Kael wrote: "Clare Boothe Luce's ode to wisecracking cattiness ... George Cukor directed—surprisingly coarsely; it's a kicking, screaming low comedy ... Goddard is a standout—she's fun. And audiences at the time loved Russell's all-out burlesque of women as jealous bitches."[15] Leslie Halliwell gave it three of four stars: "Bitchy comedy drama distinguished by an all-girl cast ('135 women with men on their minds'). An over-generous slice of real theatre, skilfully adapted, with rich sets, plenty of laughs, and some memorable scenes between fighting ladies."[16]

In 2018, The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw gave five out of five stars to "this extraordinary, almost Daliesque comedy...the absence of men has its own kind of ethical implication. It is a sort of abandonment, and the drama's no-men structure is a satirical comment on their emotional distance. Around this drama of duplicity and infidelity, Cukor creates a brilliant spectacle, halted by Shearer's moments of stunningly serious emotional devastation.[11]

On Rotten Tomatoes, The Women holds a 94% "Fresh" rating based on 64 reviews. The site's critics consensus reads, "A feast of sharp dialogue delivered by an expertly assembled cast, The Women makes the transition from stage to screen without losing a step."[17]

Box office

[edit]According to MGM records the film earned $1,610,000 in the US and Canada and $660,000 elsewhere but because of its high production cost ultimately incurred a loss of $262,000.[1] However, the film was re-released in 1947 and earned a small profit of $52,000.

Parody

[edit]On his November 5, 1939, radio broadcast, Jack Benny presented a sketch parody of The Women with all the male cast members in female roles and Mary Livingstone as the announcer.[18]

Remakes

[edit]The Women was remade as a 1956 musical comedy titled The Opposite Sex, starring June Allyson, Joan Collins, and Ann Miller.

In 1960, MGM toyed with the idea of doing an all-male remake of The Women which would have been entitled, Gentlemen's Club. Like the female version, this would have involved an all masculine cast and the plot would have involved a man (Jeffrey Hunter) who recently discovers among his friends that his wife is having an affair with another man (Earl Holliman) and after going to Reno to file for divorce and begin a new life, he later finds himself doing what he can to rectify matters later on when he discovers that the other man is only interested in money and position and he decides to win his true love back again. Although nothing ever came of this, it would have consisted of the following ensemble: Jeffrey Hunter (Martin Heal), Earl Holliman (Christopher Allen), Tab Hunter (Simon Fowler), Lew Ayres (Count Vancott), Robert Wagner (Mitchell Aarons), James Garner (Peter Day), Jerry Mathers (Little Martin), James Stewart (Mr. Heal), Ronald Reagan (Larry), Troy Donahue (Norman Blake), and Stuart Whitman (Oliver, the bartender who spills the beans about the illicit affair).

In 1977, it was remade by Rainer Werner Fassbinder for German television as Women in New York.

In 2008, Diane English wrote and directed a remake of the same title, her feature film directorial debut. The comedy starred Meg Ryan, Eva Mendes, Annette Bening, Jada Pinkett Smith, Bette Midler, and Debra Messing, and was released in 2008 by Picturehouse Entertainment, a sister company to Warner Bros. (the current owners of the 1939 version through Turner Entertainment).[19] It holds a 13% "Rotten" rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ "National Film Registry". Library of Congress, accessed October 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Women: Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ "Looking at Hollywood", Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1938

- ^ "Robert Donat Named as 'Ruined City' Star", Los Angeles Times, April 25, 1939

- ^ Brody, Richard (November 11, 2009). "The Women". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Women". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ "Mr. Cukor: A Man Among 'The Women'". The New York Times. October 1, 1939. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Hamblin, James (February 21, 2013). "A Mapped History of Taking a Train Across the United States". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (September 22, 1939). "The Screen: Four Films in Review; Featured in New Pictures Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Peter (August 16, 2018). "The Women review – Manhattan's magnificent social whirl". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Frost, Jennifer (2011). Hedda Hopper's Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism. NYU Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8147-2823-9.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (September 22, 1939). "The Screen: Four Films in Review; Featured in New Pictures Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ "The Women (1939) – Overview – TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. A William Abrahams/Owl Book. ISBN 0-8050-1366-0.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). Grafton Books. ISBN 0-06-016322-4.

- ^ The Women at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ "Jack Benny: The Jell-O Program Starring Jack Benny---1939". Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (September 19, 2007). "Femmes front 'Women'". Variety.

- ^ The Women at Rotten Tomatoes

External links

[edit]- The Women at IMDb

- The Women at AllMovie

- The Women at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Women at the TCM Movie Database

- The Women at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Women – Past and Present Archived October 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at LaFemmeReel.com

KSF

KSF