Thought experiment

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 30 min

A thought experiment is an imaginary scenario that is meant to elucidate or test an argument or theory. It is often an experiment that would be hard, impossible, or unethical to actually perform. It can also be an abstract hypothetical that is meant to test our intuitions about morality or other fundamental philosophical questions.[2][3][4][5][6]

History

[edit]The ancient Greek δείκνυμι, deiknymi, 'thought experiment', "was the most ancient pattern of mathematical proof", and existed before Euclidean mathematics,[7] where the emphasis was on the conceptual, rather than on the experimental part of a thought experiment.

Johann Witt-Hansen established that Hans Christian Ørsted was the first to use the equivalent German term Gedankenexperiment c. 1812.[8][9] Ørsted was also the first to use the equivalent term Gedankenversuch in 1820.

By 1883, Ernst Mach used Gedankenexperiment in a different sense, to denote exclusively the imaginary conduct of a real experiment that would be subsequently performed as a real physical experiment by his students.[10] Physical and mental experimentation could then be contrasted: Mach asked his students to provide him with explanations whenever the results from their subsequent, real, physical experiment differed from those of their prior, imaginary experiment.

The English term thought experiment was coined as a calque of Gedankenexperiment, and it first appeared in the 1897 English translation of one of Mach's papers.[11] Prior to its emergence, the activity of posing hypothetical questions that employed subjunctive reasoning had existed for a very long time for both scientists and philosophers. The irrealis moods are ways to categorize it or to speak about it. This helps explain the extremely wide and diverse range of the application of the term thought experiment once it had been introduced into English.

Galileo's demonstration that falling objects must fall at the same rate regardless of their masses was a significant step forward in the history of modern science. This is widely thought[12] to have been a straightforward physical demonstration, involving climbing up the Leaning Tower of Pisa and dropping two heavy weights off it, whereas in fact, it was a logical demonstration, using the thought experiment technique. The experiment is described by Galileo in his 1638 work Two New Sciences thus:

- Salviati:

If then we take two bodies whose natural speeds are different, it is clear that on uniting the two, the more rapid one will be partly retarded by the slower, and the slower will be somewhat hastened by the swifter. Do you not agree with me in this opinion?

Simplicio:You are unquestionably right.

Salviati:But if this is true, and if a large stone moves with a speed of, say, eight while a smaller moves with a speed of four, then when they are united, the system will move with a speed less than eight; but the two stones when tied together make a stone larger than that which before moved with a speed of eight. Hence the heavier body moves with less speed than the lighter; an effect which is contrary to your supposition. Thus you see how, from your assumption that the heavier body moves more rapidly than the lighter one, I infer that the heavier body moves more slowly.[13]

Uses

[edit]Thought experiments may be used to explore a hypothesis and the implementation of theories around it. They are also used in education, or for personal entertainment.[9]

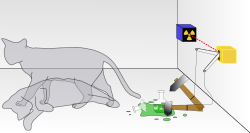

Examples of thought experiments include Schrödinger's cat, that was meant to attack the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics by showing that its assumptions could lead to the seemingly absurd condition of a cat being simultaneously alive and dead, and Maxwell's demon, which attempts to demonstrate the ability of a hypothetical finite being to violate the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

It is a common element of science-fiction stories.[14]

Thought experiments, which are well-structured, well-defined hypothetical questions that employ subjunctive reasoning (irrealis moods) – "What might happen (or, what might have happened) if . . . " – have been used to pose questions in philosophy at least since Greek antiquity, some pre-dating Socrates.[15] In physics and other sciences many thought experiments date from the 19th and especially the 20th Century, but examples can be found at least as early as Galileo.

In thought experiments, we gain new information by rearranging or reorganizing empirical data in a new way and drawing new inferences from them, or by looking at these data from a different and unusual perspective. In Galileo's thought experiment, for example, the rearrangement of empirical experience consists of the original idea of combining bodies of different weights.[16]

Thought experiments have been used in philosophy (especially ethics), physics, and other fields (such as cognitive psychology, history, political science, economics, social psychology, law, organizational studies, marketing, and epidemiology). In law, the synonym "hypothetical" is frequently used for such experiments.

Regardless of their intended goal, all thought experiments display a patterned way of thinking that is designed to allow us to explain, predict, and control events in a better and more productive way.

Theoretical consequences

[edit]In terms of their theoretical consequences, thought experiments generally:

- challenge (or even refute) a prevailing theory, often involving the device known as reductio ad absurdum, (as in Galileo's original argument, a proof by contradiction),

- confirm a prevailing theory,

- establish a new theory, or

- simultaneously refute a prevailing theory and establish a new theory through a process of mutual exclusion

Practical applications

[edit]Thought experiments can produce some very important and different outlooks on previously unknown or unaccepted theories. However, they may make those theories themselves irrelevant, and could possibly create new problems that are just as difficult, or possibly more difficult to resolve.

In terms of their practical application, thought experiments are generally created to:

- challenge the prevailing status quo (which includes activities such as correcting misinformation (or misapprehension), identify flaws in the argument(s) presented, to preserve (for the long-term) objectively established fact, and to refute specific assertions that some particular thing is permissible, forbidden, known, believed, possible, or necessary)

- extrapolate beyond (or interpolate within) the boundaries of already established fact

- predict and forecast the (otherwise) indefinite and unknowable future

- explain the past

- facilitate the retrodiction, postdiction and hindcasting of the otherwise indefinite and unknowable past

- facilitate decision making, choice, and strategy selection

- solve problems, and generate ideas;

- move current unsolved problems into another more productive problem space (e.g. functional fixedness)

- attribute causation, preventability, blame, and responsibility for specific outcomes

- assess culpability and compensatory damages in social and legal contexts

- ensure the repeat of past success

- examine the extent to which past events might have occurred differently

- ensure the future avoidance of past failures

Types

[edit]

Seven types of thought experiment, in which one reasons from causes to effects or effects to causes, can be identified:[18][19]

Prefactual

[edit]Prefactual (before the fact) thought experiments – the term prefactual was coined by Lawrence J. Sanna in 1998[20] – speculate on possible future outcomes, given the present, and ask "What will be the outcome if event E occurs?".[21][22]

Counterfactual

[edit]

Counterfactual (contrary to established fact) thought experiments – the term counterfactual was coined by Nelson Goodman in 1947,[24] extending Roderick Chisholm's (1946) notion of a "contrary-to-fact conditional"[25] – speculate on the possible outcomes of a different past;[26] and ask "What might have happened if A had happened instead of B?" (e.g., "If Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz had cooperated with each other, what would mathematics look like today?").[27][28][22]

The study of counterfactual speculation has increasingly engaged the interest of scholars in a wide range of domains such as philosophy,[29] psychology,[30] cognitive psychology,[31] history,[32] political science,[33] economics,[34] social psychology,[35] law,[36] organizational theory,[37] marketing,[38] and epidemiology.[39]

Semifactual

[edit]

Semifactual thought experiments – the term semifactual was coined by Nelson Goodman in 1947[24][40] – speculate on the extent to which things might have remained the same, despite there being a different past; and asks the question Even though X happened instead of E, would Y have still occurred? (e.g., Even if the goalie had moved left, rather than right, could he have intercepted a ball that was traveling at such a speed?).[41][22]

Semifactual speculations are an important part of clinical medicine.

Predictive

[edit]

The activity of prediction attempts to project the circumstances of the present into the future.[43][44] According to David Sarewitz and Roger Pielke (1999, p123), scientific prediction takes two forms:

- "The elucidation of invariant – and therefore predictive – principles of nature"; and

- "[Using] suites of observational data and sophisticated numerical models in an effort to foretell the behavior or evolution of complex phenomena".[45]

Although they perform different social and scientific functions, the only difference between the qualitatively identical activities of predicting, forecasting, and nowcasting is the distance of the speculated future from the present moment occupied by the user.[46] Whilst the activity of nowcasting, defined as "a detailed description of the current weather along with forecasts obtained by extrapolation up to 2 hours ahead", is essentially concerned with describing the current state of affairs, it is common practice to extend the term "to cover very-short-range forecasting up to 12 hours ahead" (Browning, 1982, p.ix).[47][48]

Hindcasting

[edit]

The activity of hindcasting involves running a forecast model after an event has happened in order to test whether the model's simulation is valid.[43][44]

Retrodiction

[edit]

The activity of retrodiction (or postdiction) involves moving backward in time, step-by-step, in as many stages as are considered necessary, from the present into the speculated past to establish the ultimate cause of a specific event (e.g., reverse engineering and forensics).[50][44]

Given that retrodiction is a process in which "past observations, events, add and data are used as evidence to infer the process(es) that produced them" and that diagnosis "involve[s] going from visible effects such as symptoms, signs and the like to their prior causes",[51] the essential balance between prediction and retrodiction could be characterized as:

regardless of whether the prognosis is of the course of the disease in the absence of treatment, or of the application of a specific treatment regimen to a specific disorder in a particular patient.[52]

Backcasting

[edit]

The activity of backcasting – the term backcasting was coined by John Robinson in 1982[54] – involves establishing the description of a very definite and very specific future situation. It then involves an imaginary moving backward in time, step-by-step, in as many stages as are considered necessary, from the future to the present to reveal the mechanism through which that particular specified future could be attained from the present.[55][56][57]

Backcasting is not concerned with predicting the future:

The major distinguishing characteristic of backcasting analyses is the concern, not with likely energy futures, but with how desirable futures can be attained. It is thus explicitly normative, involving 'working backward' from a particular future end-point to the present to determine what policy measures would be required to reach that future.[58]

According to Jansen (1994, p. 503:[59]

Within the framework of technological development, "forecasting" concerns the extrapolation of developments towards the future and the exploration of achievements that can be realized through technology in the long term. Conversely, the reasoning behind "backcasting" is: on the basis of an interconnecting picture of demands technology must meet in the future – "sustainability criteria" – to direct and determine the process that technology development must take and possibly also the pace at which this development process must take effect. Backcasting [is] both an important aid in determining the direction technology development must take and in specifying the targets to be set for this purpose. As such, backcasting is an ideal search toward determining the nature and scope of the technological challenge posed by sustainable development, and it can thus serve to direct the search process toward new – sustainable – technology.

Fields

[edit]Thought experiments have been used in a variety of fields, including philosophy, law, physics, and mathematics. In philosophy they have been used at least since classical antiquity, some pre-dating Socrates. In law, they were well known to Roman lawyers quoted in the Digest.[60] In physics and other sciences, notable thought experiments date from the 19th and, especially, the 20th century; but examples can be found at least as early as Galileo.

Philosophy

[edit]In philosophy, a thought experiment typically presents an imagined scenario with the intention of eliciting an intuitive or reasoned response about the way things are in the thought experiment. (Philosophers might also supplement their thought experiments with theoretical reasoning designed to support the desired intuitive response.) The scenario will typically be designed to target a particular philosophical notion, such as morality, or the nature of the mind or linguistic reference. The response to the imagined scenario is supposed to tell us about the nature of that notion in any scenario, real or imagined.

For example, a thought experiment might present a situation in which an agent intentionally kills an innocent for the benefit of others. Here, the relevant question is not whether the action is moral or not, but more broadly whether a moral theory is correct that says morality is determined solely by an action's consequences (See Consequentialism). John Searle imagines a man in a locked room who receives written sentences in Chinese, and returns written sentences in Chinese, according to a sophisticated instruction manual. Here, the relevant question is not whether or not the man understands Chinese, but more broadly, whether a functionalist theory of mind is correct.

It is generally hoped that there is universal agreement about the intuitions that a thought experiment elicits. (Hence, in assessing their own thought experiments, philosophers may appeal to "what we should say," or some such locution.) A successful thought experiment will be one in which intuitions about it are widely shared. But often, philosophers differ in their intuitions about the scenario.

Other philosophical uses of imagined scenarios arguably are thought experiments also. In one use of scenarios, philosophers might imagine persons in a particular situation (maybe ourselves), and ask what they would do.

For example, in the veil of ignorance, John Rawls asks us to imagine a group of persons in a situation where they know nothing about themselves, and are charged with devising a social or political organization. The use of the state of nature to imagine the origins of government, as by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, may also be considered a thought experiment. Søren Kierkegaard explored the possible ethical and religious implications of Abraham's binding of Isaac in Fear and Trembling. Similarly, Friedrich Nietzsche, in On the Genealogy of Morals, speculated about the historical development of Judeo-Christian morality, with the intent of questioning its legitimacy.

An early written thought experiment was Plato's allegory of the cave.[61] Another historic thought experiment was Avicenna's "Floating Man" thought experiment in the 11th century. He asked his readers to imagine themselves suspended in the air isolated from all sensations in order to demonstrate human self-awareness and self-consciousness, and the substantiality of the soul.[62]

Science

[edit]Scientists tend to use thought experiments as imaginary, "proxy" experiments prior to a real, "physical" experiment (Ernst Mach always argued that these gedankenexperiments were "a necessary precondition for physical experiment"). In these cases, the result of the "proxy" experiment will often be so clear that there will be no need to conduct a physical experiment at all.

Scientists also use thought experiments when particular physical experiments are impossible to conduct (Carl Gustav Hempel labeled these sorts of experiment "theoretical experiments-in-imagination"), such as Einstein's thought experiment of chasing a light beam, leading to special relativity. This is a unique use of a scientific thought experiment, in that it was never carried out, but led to a successful theory, proven by other empirical means.

Properties

[edit]Further categorization of thought experiments can be attributed to specific properties.

Possibility

[edit]In many thought experiments, the scenario would be nomologically possible, or possible according to the laws of nature. John Searle's Chinese room is nomologically possible.

Some thought experiments present scenarios that are not nomologically possible. In his Twin Earth thought experiment, Hilary Putnam asks us to imagine a scenario in which there is a substance with all of the observable properties of water (e.g., taste, color, boiling point), but is chemically different from water. It has been argued that this thought experiment is not nomologically possible, although it may be possible in some other sense, such as metaphysical possibility. It is debatable whether the nomological impossibility of a thought experiment renders intuitions about it moot.

In some cases, the hypothetical scenario might be considered metaphysically impossible, or impossible in any sense at all. David Chalmers says that we can imagine that there are zombies, or persons who are physically identical to us in every way but who lack consciousness. This is supposed to show that physicalism is false. However, some argue that zombies are inconceivable: we can no more imagine a zombie than we can imagine that 1+1=3. Others have claimed that the conceivability of a scenario may not entail its possibility.

Causal reasoning

[edit]The first characteristic pattern that thought experiments display is their orientation in time.[63] They are either:

- Antefactual speculations: experiments that speculate about what might have happened prior to a specific, designated event, or

- Postfactual speculations: experiments that speculate about what may happen subsequent to (or consequent upon) a specific, designated event.

The second characteristic pattern is their movement in time in relation to "the present moment standpoint" of the individual performing the experiment; namely, in terms of:

- Their temporal direction: are they past-oriented or future-oriented?

- Their temporal sense:

- (a) in the case of past-oriented thought experiments, are they examining the consequences of temporal "movement" from the present to the past, or from the past to the present? or,

- (b) in the case of future-oriented thought experiments, are they examining the consequences of temporal "movement" from the present to the future, or from the future to the present?

Relation to real experiments

[edit]The relation to real experiments can be quite complex, as can be seen again from an example going back to Albert Einstein. In 1935, with two coworkers, he published a paper on a newly created subject called later the EPR effect (EPR paradox). In this paper, starting from certain philosophical assumptions,[64] on the basis of a rigorous analysis of a certain, complicated, but in the meantime assertedly realizable model, he came to the conclusion that quantum mechanics should be described as "incomplete". Niels Bohr asserted a refutation of Einstein's analysis immediately, and his view prevailed.[65][66][67] After some decades, it was asserted that feasible experiments could prove the error of the EPR paper. These experiments tested the Bell inequalities published in 1964 in a purely theoretical paper. The above-mentioned EPR philosophical starting assumptions were considered to be falsified by the empirical fact (e.g. by the optical real experiments of Alain Aspect).

Thus thought experiments belong to a theoretical discipline, usually to theoretical physics, but often to theoretical philosophy. In any case, it must be distinguished from a real experiment, which belongs naturally to the experimental discipline and has "the final decision on true or not true", at least in physics.

Interactivity

[edit]Thought experiments can also be interactive where the author invites people into his thought process through providing alternative paths with alternative outcomes within the narrative, or through interaction with a programmed machine, like a computer program.

Thanks to the advent of the Internet, the digital space has lent itself as a new medium for a new kind of thought experiments. The philosophical work of Stefano Gualeni, for example, focuses on the use of virtual worlds to materialize thought experiments and to playfully negotiate philosophical ideas.[68] His arguments were originally presented in his 2015 book Virtual Worlds as Philosophical Tools.[69]

Gualeni's argument is that the history of philosophy has, until recently, merely been the history of written thought, and digital media can complement and enrich the limited and almost exclusively linguistic approach to philosophical thought.[69][68][70] He considers virtual worlds (like those interactively encountered in videogames) to be philosophically viable and advantageous. This is especially the case in thought experiments, when the recipients of a certain philosophical notion or perspective are expected to objectively test and evaluate different possible courses of action, or in cases where they are confronted with interrogatives concerning non-actual or non-human phenomenologies.[69][68][70]

Examples

[edit]Humanities

[edit]Physics

[edit]- Bell's spaceship paradox (special relativity)

- Brownian ratchet (Richard Feynman's "perpetual motion" machine that does not violate the second law and does no work at thermal equilibrium)

- Bucket argument – argues that space is absolute, not relational

- Dyson sphere

- Einstein's box

- Elitzur–Vaidman bomb-tester (quantum mechanics)

- EPR paradox (quantum mechanics) (forms of this have been performed)

- Everett phone (quantum mechanics)

- Feynman sprinkler (classical mechanics)

- Galileo's Leaning Tower of Pisa experiment (rebuttal of Aristotelian Gravity)

- Galileo's ship (classical relativity principle) 1632

- GHZ experiment (quantum mechanics)

- Heisenberg's microscope (quantum mechanics)

- Kepler's Dream (change of point of view as support for the Copernican hypothesis)

- Ladder paradox (special relativity)

- Laplace's demon

- Maxwell's demon (thermodynamics) 1871

- Mermin's device (quantum mechanics)

- Moving magnet and conductor problem

- Newton's cannonball (Newton's laws of motion)

- Popper's experiment (quantum mechanics)

- Quantum pseudo telepathy (quantum mechanics)

- Quantum suicide and immortality (quantum mechanics)

- Renninger negative-result experiment (quantum mechanics)

- Schrödinger's cat (quantum mechanics)[1]

- Sticky bead argument (general relativity)

- The Monkey and the Hunter (gravitation)

- Twin paradox (special relativity)

- Wheeler's delayed choice experiment (quantum mechanics)

- Wigner's friend (quantum mechanics)

Philosophy

[edit]- Artificial brain

- Avicenna's Floating Man

- Beetle in a box

- Bellum omnium contra omnes

- Big Book (ethics)

- Brain-in-a-vat (epistemology, philosophy of mind)

- Brainstorm machine

- Buridan's ass

- Changing places (reflexive monism, philosophy of mind)

- Chesterton's fence

- China brain (physicalism, philosophy of mind)

- Chinese room (philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence, cognitive science)

- Coherence (philosophical gambling strategy)

- Condillac's Statue (epistemology)

- Experience machine (ethics)

- Gettier problem (epistemology)

- Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān (epistemology)

- Hilary Putnam's Twin Earth thought experiment in the philosophy of language and philosophy of mind

- If a tree falls in a forest

- Inverted spectrum

- Kavka's toxin puzzle

- Mary's room (philosophy of mind)

- Molyneux's Problem (admittedly, this oscillated between empirical and a-priori assessment)

- Newcomb's paradox

- Original position (politics)

- Philosophical zombie (philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence, cognitive science)

- Plank of Carneades

- Roko's basilisk

- Ship of Theseus, The (concept of identity)

- Shoemaker's "Time Without Change" (metaphysics)

- Simulated reality (philosophy, computer science, cognitive science)

- Social contract theories

- Survival lottery (ethics)

- Swamp man (personal identity, philosophy of mind)

- Teleportation (metaphysics)

- The transparent eyeball

- The violinist (ethics)

- Ticking time bomb scenario (ethics)

- Trolley problem (ethics)

- Utility monster (ethics)

- Zeno's paradoxes (classical Greek problems of the infinite)

Mathematics

[edit]- Balls and vase problem (infinity and cardinality)

- Gabriel's Horn (infinity)

- Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel (infinity)

- Infinite monkey theorem (probability)

- Lottery paradox (probability)

- Sleeping beauty paradox (probability)

Biology

[edit]Computer science

[edit]- Braitenberg vehicles (robotics, neural control and sensing systems)

- Dining Philosophers

- Two Generals' Problem

Economics

[edit]See also

[edit]- Alternate history

- Aporia – State of puzzlement or expression of doubt, in philosophy and rhetoric

- Black box – System where only the inputs and outputs can be viewed, and not its implementation

- Brainstorm machine

- Ding an sich

- Einstein's thought experiments

- Futures studies

- Futures techniques

- Heuristic

- Intuition pump – Type of thought experiment

- Koan

- Mathematical proof

- N-universes

- Possible world

- Scenario planning

- Scenario test

- Theoretical physics

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bild, Marius; Fadel, Matteo; Yang, Yu; et al. (20 April 2023). "Schrödinger cat states of a 16-microgram mechanical oscillator". Science. 380 (6642): 274–278. arXiv:2211.00449. Bibcode:2023Sci...380..274B. doi:10.1126/science.adf7553. PMID 37079693.

- ^ Miyamoto, Kentaro; Rushworth, Matthew F.S.; Shea, Nicholas (1 May 2023). "Imagining the future self through thought experiments". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 27 (5): 446–455. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2023.01.005. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 36801162.

- ^ Gendler, Tamar Szabó (1 January 2022). "Thought Experiments Rethought—and Reperceived". Philosophy of Science. 71 (5): 1152–1163. doi:10.1086/425239. ISSN 0031-8248. S2CID 144114290.

- ^ Grush, Rick (1 June 2004). "The emulation theory of representation: Motor control, imagery, and perception". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2 7 (3): 377–396. doi:10.1017/S0140525X04000093. ISSN 0140-525X. PMID 15736871. S2CID 514252.

- ^ Aronowitz, S., & Lombrozo, T. (2020). Learning through simulation. Philosophers' Imprint, 20(1), 1-18.

- ^ Bourget, David; Chalmers, David J. (25 July 2023). "Philosophers on Philosophy: The 2020 PhilPapers Survey". Philosophers' Imprint. 23 (1). doi:10.3998/phimp.2109. ISSN 1533-628X.

- ^ Szábo, Árpád. (1958) " 'Deiknymi' als Mathematischer Terminus fur 'Beweisen' ", Maia N.S. 10 pp. 1–26 as cited by Imre Lakatos (1976) in Proofs and Refutations p. 9. (John Worrall and Elie Zahar, eds.) Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-21078-X. The English translation of the title of Szábo's article is "'Deiknymi' as a mathematical expression for 'to prove'", as translated by András Máté Máté, András (Fall 2006). "Árpád Szabó and Imre Lakatos, or the Relation Between History and Philosophy of Mathematics" (PDF). Perspectives on Science. 14 (3): 282–301 especially pp. 285, 288. doi:10.1162/posc.2006.14.3.282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012.

- ^ Witt-Hansen (1976). Although Experiment is a German word, it is derived from Latin. The synonym Versuch has purely Germanic roots.

- ^ a b Brown, James Robert; Fehige, Yiftach (30 September 2019) [1996]. "Thought Experiments". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Mach, Ernst (1883), The Science of Mechanics (6th edition, translated by Thomas J. McCormack), LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court, 1960. pp. 32–41, 159–62.

- ^ Mach, Ernst (1897), "On Thought Experiments", in Knowledge and Error (translated by Thomas J. McCormack and Paul Foulkes), Dordrecht Holland: Reidel, 1976, pp. 134-47.

- ^ Cohen, Martin, "Wittgenstein's Beetle and Other Classic Thought Experiments", Blackwell, (Oxford), 2005, pp. 55–56.

- ^ "Galileo on Aristotle and Acceleration". Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ "SFE: Thought Experiment". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Rescher, N. (1991), "Thought Experiment in Pre-Socratic Philosophy", in Horowitz, T.; Massey, G.J. (eds.), Thought Experiments in Science and philosophy, Rowman & Littlefield, (Savage), pp. 31–41.

- ^ Brendal, Elke, "Intuition Pumps and the Proper Use of Thought Experiments". Dialectica. V.58, Issue 1, pp. 89–108, March 2004

- ^ Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 143.

- ^ Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 138-159.

- ^ Garbey, M., Joerger, G. & Furr, S. (2023), "Application of Digital Twin and Heuristic Computer Reasoning to Workflow Management: Gastroenterology Outpatient Centers Study", Journal of Surgery and Research, Vol.6, No.1, pp. 104–129.

- ^ Sanna, L.J., "Defensive Pessimism and Optimism: The Bitter-Sweet Influence of Mood on Performance and Prefactual and Counterfactual Thinking", Cognition and Emotion, Vol.12, No.5, (September 1998), pp. 635–665. (Sanna used the term prefactual to distinguish these sorts of thought experiment from both semifactuals and counterfactuals.)

- ^ See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 143.

- ^ a b c Also, see Garbey, Joerger & Furr (2023), pp. 112, 126.

- ^ a b Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 144.

- ^ a b Goodman, N., "The Problem of Counterfactual Conditionals", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.44, No.5, (27 February 1947), pp. 113–128.

- ^ Chisholm, R.M., "The Contrary-to-Fact Conditional", Mind, Vol.55, No.220, (October 1946), pp. 289–307.

- ^ Roger Penrose (Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), 1994, p. 240) considers counterfactuals to be "things that might have happened, although they did not in fact happen".

- ^ In 1748, when defining causation, David Hume referred to a counterfactual case: "…we may define a cause to be an object, followed by another, and where all objects, similar to the first, are followed by objects similar to the second. Or in other words, where, if the first object had not been, the second never had existed …" (Hume, D. (Beauchamp, T.L., ed.), An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), 1999, (7), p. 146.)

- ^ See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 143–144.

- ^ Goodman, N., "The Problem of Counterfactual Conditionals", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.44, No.5, (27 February 1947), pp. 113–128; Brown, R, & Watling, J., "Counterfactual Conditionals", Mind, Vol.61, No.242, (April 1952), pp. 222–233; Parry, W.T., "Reëxamination of the Problem of Counterfactual Conditionals", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.54, No.4, (14 February 1957), pp. 85–94; Cooley, J.C., "Professor Goodman's Fact, Fiction, & Forecast", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.54, No.10, (9 May 1957), pp. 293–311; Goodman, N., "Parry on Counterfactuals", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.54, No.14, (4 July 1957), pp. 442–445; Goodman, N., "Reply to an Adverse Ally", The Journal of Philosophy, Vol.54, No.17, (15 August 1957), pp. 531–535; Lewis, D., Counterfactuals, Basil Blackwell, (Oxford), 1973, etc.

- ^ Fillenbaum, S., "Information Amplified: Memory for Counterfactual Conditionals", Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol.102, No.1, (January 1974), pp. 44–49; Crawford, M.T. & McCrea, S.M., "When Mutations meet Motivations: Attitude Biases in Counterfactual Thought", Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Vol.40, No.1, (January 2004), pp. 65–74, etc.

- ^ Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A., "The Simulation Heuristic", pp. 201–208 in Kahneman, D., Slovic, P. & Tversky, A. (eds), Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1982; Sherman, S.J. & McConnell, A.R., "Dysfunctional Implications of Counterfactual Thinking: When Alternatives to reality Fail Us", pp. 199–231 in Roese, N.J. & Olson, J.M. (eds.), What Might Have Been: The Social Psychology of Counterfactual Thinking, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, (Mahwah), 1995;Nasco, S.A. & Marsh, K.L., "Gaining Control Through Counterfactual Thinking", Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol.25, No.5, (May 1999), pp. 556–568; McCloy, R. & Byrne, R.M.J., "Counterfactual Thinking About Controllable Events", Memory and Cognition, Vol.28, No.6, (September 2000), pp. 1071–1078; Byrne, R.M.J., "Mental Models and Counterfactual Thoughts About What Might Have Been", Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol.6, No.10, (October 2002), pp. 426–431; Thompson, V.A. & Byrne, R.M.J., "Reasoning Counterfactually: Making Inferences About Things That Didn't Happen", Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, Vol.28, No.6, (November 2002), pp. 1154–1170, etc.

- ^ Greenberg, M. (ed.), The Way It Wasn't: Great Science Fiction Stories of Alternate History, Citadel Twilight, (New York), 1996; Dozois, G. & Schmidt, W. (eds.), Roads Not Taken: Tales of Alternative History, The Ballantine Publishing Group, (New York), 1998; Sylvan, D. & Majeski, S., "A Methodology for the Study of Historical Counterfactuals", International Studies Quarterly, Vol.42, No.1, (March 1998), pp. 79–108; Ferguson, N., (ed.), Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals, Basic Books, (New York), 1999; Cowley, R. (ed.), What If?: The World's Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might have Been, Berkley Books, (New York), 2000; Cowley, R. (ed.), What If? 2: Eminent Historians Imagine What Might have Been, G.P. Putnam's Sons, (New York), 2001, etc.

- ^ Fearon, J.D., "Counterfactuals and Hypothesis Testing in Political Science", World Politics, Vol.43, No.2, (January 1991), pp. 169–195; Tetlock, P.E. & Belkin, A. (eds.), Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics, Princeton University Press, (Princeton), 1996; Lebow, R.N., "What's so Different about a Counterfactual?", World Politics, Vol.52, No.4, (July 2000), pp. 550–585; Chwieroth, J.M., "Counterfactuals and the Study of the American Presidency", Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol.32, No.2, (June 2002), pp. 293–327, etc.

- ^ Cowan, R. & Foray, R., "Evolutionary Economics and the Counterfactual Threat: On the Nature and Role of Counterfactual History as an Empirical Tool in Economics", Journal of Evolutionary Economics, Vol.12, No.5, (December 2002), pp. 539–562, etc.

- ^ Roese, N.J. & Olson, J.M. (eds.), What Might Have Been: The Social Psychology of Counterfactual Thinking, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, (Mahwah), 1995; Sanna, L.J., "Defensive Pessimism, Optimism, and Simulating Alternatives: Some Ups and Downs of Prefactual and Counterfactual Thinking", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol.71, No.5, (November 1996), pp. 1020–1036; Roese, N.J., "Counterfactual Thinking", Psychological Bulletin, Vol.121, No.1, (January 1997), pp. 133–148; Sanna, L.J., "Defensive Pessimism and Optimism: The Bitter-Sweet Influence of Mood on Performance and Prefactual and Counterfactual Thinking", Cognition and Emotion, Vol.12, No.5, (September 1998), pp. 635–665; Sanna, L.J. & Turley-Ames, K.J., "Counterfactual Intensity", European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.30, No.2, (March/April 2000), pp. 273–296; Sanna, L.J., Parks, C.D., Meier, S., Chang, E.C., Kassin, B.R., Lechter, J.L., Turley-Ames, K.J. & Miyake, T.M., "A Game of Inches: Spontaneous Use of Counterfactuals by Broadcasters During Major League Baseball Playoffs", Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol.33, No.3, (March 2003), pp. 455–475, etc.

- ^ Strassfeld, R.N., "If...: Counterfactuals in the Law", George Washington Law Review, Volume 60, No.2, (January 1992), pp. 339–416; Spellman, B.A. & Kincannon, A., "The Relation between Counterfactual ("but for") and Causal reasoning: Experimental Findings and Implications for Juror's Decisions", Law and Contemporary Problems, Vol.64, No.4, (Autumn 2001), pp. 241–264; Prentice, R.A. & Koehler, J.J., "A Normality Bias in Legal Decision Making", Cornell Law Review, Vol.88, No.3, (March 2003), pp. 583–650, etc.

- ^ Creyer, E.H. & Gürhan, Z., "Who's to Blame? Counterfactual Reasoning and the Assignment of Blame", Psychology and Marketing, Vol.14, No.3, (May 1997), pp. 209–307; Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W.W., van der Plight, J., Manstead, A.S.R., van Empelen, P., & Reinderman, D., "Emotional Reactions to the Outcomes of Decisions: The Role of Counterfactual Thought in the Experience of Regret and Disappointment", Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol.75, No.2, (August 1998), pp. 117–141; Naquin, C.E. & Tynan, R.O., "The Team Halo Effect: Why Teams Are Not Blamed for Their Failures", Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol.88, No.2, (April 2003), pp. 332–340; Naquin, C.E., "The Agony of Opportunity in Negotiation: Number of Negotiable Issues, Counterfactual Thinking, and Feelings of Satisfaction", Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol.91, No.1, (May 2003), pp. 97–107, etc.

- ^ Hetts, J.J., Boninger, D.S., Armor, D.A., Gleicher, F. & Nathanson, A., "The Influence of Anticipated Counterfactual Regret on Behavior", Psychology & Marketing, Vol.17, No.4, (April 2000), pp. 345–368; Landman, J. & Petty, R., ""It Could Have Been You": How States Exploit Counterfactual Thought to Market Lotteries", Psychology & Marketing, Vol.17, No.4, (April 2000), pp. 299–321; McGill, A.L., "Counterfactual Reasoning in Causal Judgements: Implications for Marketing", Psychology & Marketing, Vol.17, No.4, (April 2000), pp. 323–343; Roese, N.J., "Counterfactual Thinking and Marketing: Introduction to the Special Issue", Psychology & Marketing', Vol.17, No.4, (April 2000), pp. 277–280; Walchli, S.B. & Landman, J., "Effects of Counterfactual Thought on Postpurchase Consumer Affect", Psychology & Marketing, Vol.20, No.1, (January 2003), pp. 23–46, etc.

- ^ Randerson, J., "Fast action would have saved millions", New Scientist, Vol.176, No.2372, (7 December 2002), p. 19; Haydon, D.T., Chase-Topping, M., Shaw, D.J., Matthews, L., Friar, J.K., Wilesmith, J. & Woolhouse, M.E.J., "The Construction and Analysis of Epidemic Trees With Reference to the 2001 UK Foot-and-Mouth Outbreak", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences, Vol.270, No.1511, (22 January 2003), pp. 121–127, etc.

- ^ Goodman's original concept has been subsequently developed and expanded by (a) Daniel Cohen (Cohen, D., "Semifactuals, Even-Ifs, and Sufficiency", International Logic Review, Vol.16, (1985), pp. 102–111), (b) Stephen Barker (Barker, S., "Even, Still and Counterfactuals", Linguistics and Philosophy, Vol.14, No.1, (February 1991), pp. 1–38; Barker, S., "Counterfactuals, Probabilistic Counterfactuals and Causation", Mind, Vol.108, No.431, (July 1999), pp. 427–469), and (c) Rachel McCloy and Ruth Byrne (McCloy, R. & Byrne, R.M.J., "Semifactual 'Even If' Thinking", Thinking and Reasoning, Vol.8, No.1, (February 2002), pp. 41–67).

- ^ See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 144.

- ^ a b Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 145.

- ^ a b See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 145.

- ^ a b c Also, see Garbey, Joerger & Furr (2023), pp. 112, 127.

- ^ Sarewitz, D. & Pielke, R., "Prediction in Science and Policy", Technology in Society, Vol.21, No.2, (April 1999), pp. 121–133.

- ^ Nowcasting (obviously based on forecasting) is also known as very-short-term forecasting; thus, also indicating a very-short-term, mid-range, and long-range forecasting continuum.

- ^ Browning, K.A. (ed.), Nowcasting, Academic Press, (London), 1982.

- ^ Murphy, and Brown – Murphy, A.H. & Brown, B.G., "Similarity and Analogical Reasoning: A Synthesis", pp. 3–15 in Browning, K.A. (ed.),

Nowcasting, Academic Press, (London), 1982 – describe a large range of specific applications for meteorological nowcasting over a wide range of user demands:

(1) Agriculture: (a) wind and precipitation forecasts for effective seeding and spraying from aircraft; (b) precipitation forecasts to minimize damage to seedlings; (c) minimum temperature, dewpoint, cloud cover, and wind speed forecasts to protect crops from frost; (d) maximum temperature forecasts to reduce adverse effects of high temperatures on crops and livestock; (e) humidity and cloud cover forecasts to prevent fungal disease crop losses; (f) hail forecasts to minimize damage to livestock and greenhouses; (g) precipitation, temperature, and dewpoint forecasts to avoid during- and after-harvest losses due to crops rotting in the field; (h) precipitation forecasts to minimize losses in drying raisins; and (i) humidity forecasts to reduce costs and losses resulting from poor conditions for drying tobacco.

(2) Construction: (a) precipitation and wind speed forecasts to avoid damage to finished work (e.g. concrete) and minimize costs of protecting exposed surfaces, structures, and work sites; and (b) precipitation, wind speed, and high/low-temperature forecasts to schedule work in an efficient manner.

(3) Energy: (a) temperature, humidity, wind, cloud, etc. forecasts to optimize procedures related to generation and distribution of electricity and gas; (b) forecasts of thunderstorms, strong winds, low temperatures, and freezing precipitation minimize damage to lines and equipment and to schedule repairs.

(4) Transportation: (a) ceiling height and visibility, winds and turbulence, and surface ice and snow forecasts minimize risk, maximize efficiency in pre-flight and in-flight decisions and other adjustments to weather-related fluctuations in traffic; (b) forecasts of wind speed and direction, as well as severe weather and icing conditions along flight paths facilitate optimal airline route planning; (c) forecasts of snowfall, precipitation, and other storm-related events allow truckers, motorists, and public transportation systems to avoid damage to weather-sensitive goods, select optimum routes, prevent accidents, minimize delays, and maximize revenues under conditions of adverse weather.

(5) Public Safety & General Public: (a) rain, snow, wind, and temperature forecasts assist the general public in planning activities such as commuting, recreation, and shopping; (b) forecasts of temperature/humidity extremes (or significant changes) alert hospitals, clinics, and the public to weather conditions that may seriously aggravate certain health-related illnesses; (c) forecasts related to potentially dangerous or damaging natural events (e.g., tornados, severe thunderstorms, severe winds, storm surges, avalanches, precipitation, floods) minimize loss of life and property damage; and (d) forecasts of snowstorms, surface icing, visibility, and other events (e.g. floods) enable highway maintenance and traffic control organizations to take appropriate actions to reduce risks of traffic accidents and protect roads from damage. - ^ Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 146.

- ^ See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 146.

- ^ p. 24, Einhorn, H.J. & Hogarth, R.M., "Prediction, Diagnosis, and Causal Thinking in Forecasting", Journal of Forecasting, (January–March 1982), Vol.1, No.1, pp. 23–36.

- ^ "…We consider diagnostic inference to be based on causal thinking, although in doing diagnosis one has to mentally reverse the time order in which events were thought to have occurred (hence the term "backward inference"). On the other hand, predictions involve forward inference; i.e., one goes forward in time from present causes to future effects. However, it is important to recognize the dependence of forward inference/prediction on backward inference/diagnosis. In particular, it seems likely that success in predicting the future depends to a considerable degree on making sense of the past. Therefore, people are continually engaged in shifting between forward and backward inference in both making and evaluating forecasts. Indeed, this can be eloquently summarized by Kierkegaard's observation that 'Life can only be understood backward; but it must be lived forwards' …"(Einhorn & Hogarth, 1982, p. 24).

- ^ Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). p. 147.

- ^ See Robinson, J.B., "Energy Backcasting: A Proposed Method of Policy Analysis", Energy Policy, Vol.10, No.4 (December 1982), pp. 337–345; Robinson, J.B., "Unlearning and Backcasting: Rethinking Some of the Questions We Ask About the Future", Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol.33, No.4, (July 1988), pp. 325–338; Robinson, J., "Future Subjunctive: Backcasting as Social Learning", Futures, Vol.35, No.8, (October 2003), pp. 839–856.

- ^ See Yeates, Lindsay Bertram (2004). Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach (Thesis). pp. 139–140, 141–142, 146–147.

- ^ Also, see Garbey, Joerger & Furr (2023), pp. 112, 127–128.

- ^ Robinson's backcasting approach is very similar to the anticipatory scenarios of Ducot and Lubben (Ducot, C. & Lubben, G.J., "A Typology for Scenarios", Futures, Vol.11, No.1, (February 1980), pp. 51–57), and Bunn and Salo (Bunn, D.W. & Salo, A.A., "Forecasting with scenarios", European Journal of Operational Research, Vol.68, No.3, (13 August 1993), pp. 291–303).

- ^ p. 814, Dreborg, K.H., "Essence of Backcasting", Futures, Vol.28, No.9, (November 1996), pp. 813–828.

- ^ Jansen, L., "Towards a Sustainable Future, en route with Technology", pp. 496–525 in Dutch Committee for Long-Term Environmental Policy (ed.), The Environment: Towards a Sustainable Future (Environment & Policy, Volume 1), Kluwer Academic Publishers, (Dortrecht), 1994.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Pandects "every logical rule of law is capable of illumination from the law of the Pandects."

- ^ Plato. Rep. vii, I–III, 514–518B.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (1996), History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 315, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13159-6.

- ^ Yeates, 2004, pp. 138–143.

- ^ Jaynes, E.T. (1989).Clearing up the Mysteries, opening talk at the 8th International MAXENT Workshop, St John's College, Cambridge UK.

- ^ French, A.P., Taylor, E.F. (1979/1989). An Introduction to Quantum Physics, Van Nostrand Reinhold (International), London, ISBN 0-442-30770-5.

- ^ Wheeler, J.A, Zurek, W.H., editors (1983). Quantum Theory and Measurement, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- ^ d'Espagnat, B. (2006). On Physics and Philosophy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, ISBN 978-0-691-11964-9

- ^ a b c Gualeni, Stefano (21 April 2022). "Philosophical Games". Encyclopedia of Ludic Terms. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Gualeni, Stefano (2015). Virtual Worlds as Philosophical Tools: How to Philosophize with a Digital Hammer. Basingstoke (UK): Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-137-52178-1.

- ^ a b Gualeni, Stefano (2016). "Self-reflexive videogames: observations and corollaries on virtual worlds as philosophical artifacts". G a M e, the Italian Journal of Game Studies. 1, 5.

- ^ While the problem presented in this short story's scenario is not unique, it is extremely unusual. Most thought experiments are intentionally (or, even, sometimes unintentionally) skewed towards the inevitable production of a particular solution to the problem posed; and this happens because of the way that the problem and the scenario are framed in the first place. In the case of The Lady, or the Tiger?, the way that the story unfolds is so "end-neutral" that, at the finish, there is no "correct" solution to the problem. Therefore, all that one can do is to offer one's own innermost thoughts on how the account of human nature that has been presented might unfold – according to one's own experience of human nature – which is, obviously, the purpose of the entire exercise. The extent to which the story can provoke such an extremely wide range of (otherwise equipollent) predictions of the participants' subsequent behaviour is one of the reasons the story has been so popular over time.

Further reading

[edit]- Brendal, Elke, "Intuition Pumps and the Proper Use of Thought Experiments", Dialectica, Vol.58, No.1, (March 2004, pp. 89–108. Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Ćorić, Dragana (2020), "The Importance of Thought Experiments", Journal of Eastern-European Criminal Law, Vol.2020, No.1, (2020), pp. 127–135.

- Cucic, D.A. & Nikolic, A.S., "A short insight about thought experiment in modern physics", 6th International Conference of the Balkan Physical Union BPU6, Istanbul – Turkey, 2006.

- Dennett, D.C., "Intuition Pumps", pp. 180–197 in Brockman, J., The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution, Simon & Schuster, (New York), 1995. ISBN 978-0-684-80359-3

- Galton, F., "Statistics of Mental Imagery", Mind, Vol.5, No.19, (July 1880), pp. 301–318.

- Hempel, C.G., "Typological Methods in the Natural and Social Sciences", pp. 155–171 in Hempel, C.G. (ed.), Aspects of Scientific Explanation and Other Essays in the Philosophy of Science, The Free Press, (New York), 1965.

- Jacques, V., Wu, E., Grosshans, F., Treussart, F., Grangier, P. Aspect, A., & Roch, J. (2007). Experimental Realization of Wheeler's Delayed-Choice Gedanken Experiment, Science, 315, p. 966–968.

- Kuhn, T., "A Function for Thought Experiments", in The Essential Tension (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), pp. 240–265.

- Mach, E., "On Thought Experiments", pp. 134–147 in Mach, E., Knowledge and Error: Sketches on the Psychology of Enquiry, D. Reidel Publishing Co., (Dordrecht), 1976. [Translation of Erkenntnis und Irrtum (5th edition, 1926.].

- Popper, K., "On the Use and Misuse of Imaginary Experiments, Especially in Quantum Theory", pp. 442–456, in Popper, K., The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Harper Torchbooks, (New York), 1968.

- Stuart, M. T., Fehige, Y. and Brown, J. R. (2018). The Routledge Companion to Thought Experiments. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73508-7

- Witt-Hansen, J., "H.C. Ørsted, Immanuel Kant and the Thought Experiment", Danish Yearbook of Philosophy, Vol.13, (1976), pp. 48–65.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams, Scott, God's Debris: A Thought Experiment, Andrews McMeel Publishing, (USA), 2001

- Browning, K.A. (ed.), Nowcasting, Academic Press, (London), 1982.

- Buzzoni, M., Thought Experiment in the Natural Sciences, Koenigshausen+Neumann, Wuerzburg 2008

- Cohen, Martin, "Wittgenstein's Beetle and Other Classic Thought Experiments", Blackwell (Oxford) 2005

- Cohnitz, D., Gedankenexperimente in der Philosophie, Mentis Publ., (Paderborn, Germany), 2006.

- Craik, K.J.W., The Nature of Explanation, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1943.

- Cushing, J.T., Philosophical Concepts in Physics: The Historical Relation Between Philosophy and Scientific Theories, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1998.

- DePaul, M. & Ramsey, W. (eds.), Rethinking Intuition: The Psychology of Intuition and Its Role in Philosophical Inquiry, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, (Lanham), 1998.

- Gendler, T.S. & Hawthorne, J., Conceivability and Possibility, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), 2002.

- Gendler, T.S., Thought Experiment: On the Powers and Limits of Imaginary Cases, Garland, (New York), 2000.

- Häggqvist, S., Thought Experiments in Philosophy, Almqvist & Wiksell International, (Stockholm), 1996.

- Hanson, N.R., Patterns of Discovery: An Inquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1962.

- Harper, W.L., Stalnaker, R. & Pearce, G. (eds.), Ifs: Conditionals, Belief, Decision, Chance, and Time, D. Reidel Publishing Co., (Dordrecht), 1981.

- Hesse, M.B., Models and Analogies in Science, Sheed and Ward, (London), 1963.

- Holyoak, K.J. & Thagard, P., Mental Leaps: Analogy in Creative Thought, A Bradford Book, The MIT Press, (Cambridge), 1995.

- Horowitz, T. & Massey, G.J. (eds.), Thought Experiments in Science and Philosophy, Rowman & Littlefield, (Savage), 1991.

- Kahn, H., Thinking About the Unthinkable, Discus Books, (New York), 1971.

- Kuhne, U., Die Methode des Gedankenexperiments, Suhrkamp Publ., (Frankfurt/M, Germany), 2005.

- Leatherdale, W.H., The Role of Analogy, Model and Metaphor in Science, North-Holland Publishing Company, (Amsterdam), 1974.

- Ørsted, Hans Christian (1997). Selected Scientific Works of Hans Christian Ørsted. Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-04334-0.. Translated to English by Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson, and Ole Knudsen, (translators 1997).

- Roese, N.J. & Olson, J.M. (eds.), What Might Have Been: The Social Psychology of Counterfactual Thinking, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, (Mahwah), 1995.

- Shanks, N. (ed.), Idealization IX: Idealization in Contemporary Physics (Poznan Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities, Volume 63), Rodopi, (Amsterdam), 1998.

- Shick, T. & Vaugn, L., Doing Philosophy: An Introduction through Thought Experiments (Second Edition), McGraw Hill, (New York), 2003.

- Sorensen, R.A., Thought Experiments, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), 1992.

- Tetlock, P.E. & Belkin, A. (eds.), Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics, Princeton University Press, (Princeton), 1996.

- Thomson, J.J. {Parent, W. (ed.)}, Rights, Restitution, and Risks: Essays in Moral Theory, Harvard University Press, (Cambridge), 1986.

- Vosniadou, S. & Ortony. A. (eds.), Similarity and Analogical Reasoning, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1989.

- Wilkes, K.V., Real People: Personal Identity without Thought Experiments, Oxford University Press, (Oxford), 1988.

- Yeates, L.B., Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach, Graduate Diploma in Arts (By Research) Dissertation, University of New South Wales, 2004.

External links

[edit]- Thought experiment at PhilPapers

- Thought experiment at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Stevinus, Galileo, and Thought Experiments Short essay by S. Abbas Raza of 3 Quarks Daily

- Thought experiment generator, a visual aid to running your own thought experiment

KSF

KSF