Thrips

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

| Thrips Temporal range: Permian – recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Winged and wingless forms | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Clade: | Eumetabola |

| (unranked): | Paraneoptera |

| Order: | Thysanoptera Haliday, 1836 |

| Suborders & Families | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Physopoda[1] | |

Thrips (order Thysanoptera) are minute (mostly 1 mm (0.04 in) long or less), slender insects with fringed wings and unique asymmetrical mouthparts. Entomologists have described approximately 7,700 species. They fly only weakly and their feathery wings are unsuitable for conventional flight; instead, thrips exploit an unusual mechanism, clap and fling, to create lift using an unsteady circulation pattern with transient vortices near the wings.

Thrips are a functionally diverse group; many of the known species are fungivorous. A small proportion of the species are serious pests of commercially important crops. Some of these serve as vectors for over 20 viruses that cause plant disease, especially the Tospoviruses. Many flower-dwelling species bring benefits as pollinators, with some predatory thrips feeding on small insects or mites. In the right conditions, such as in greenhouses, invasive species can exponentially increase in population size and form large swarms because of a lack of natural predators coupled with their ability to reproduce asexually, making them destructive to crops. Their identification to species by standard morphological characteristics is often challenging.

Naming and etymology

[edit]The first recorded mention of thrips dates from the 17th century, and a sketch was made by Philippo Bonanni, a Catholic priest, in 1691. Swedish entomologist Baron Charles De Geer described two species in the genus Physapus in 1744, and Linnaeus in 1746 added a third species and named this group of insects Thrips. In 1836 the Irish entomologist Alexander Henry Haliday described 41 species in 11 genera and proposed the order name of Thysanoptera. The first monograph on the group was published in 1895 by Heinrich Uzel,[2] who is regarded by Fedor et al. as the father of Thysanoptera studies.[3]

The generic and English name thrips is a direct transliteration of the Ancient Greek word θρίψ, thrips, meaning "woodworm".[4] Like some other animal-names (such as sheep, deer, and moose) in English the word "thrips" expresses both the singular and plural, so there may be many thrips or a single thrips. Other common names for thrips include thunderflies, thunderbugs, storm flies, thunderblights, storm bugs, corn fleas, corn flies, corn lice, freckle bugs, harvest bugs, and physopods.[5][6][7] The older group name "physopoda" references the bladder-like tips to the tarsi of the legs. The name of the order, Thysanoptera, is constructed from the ancient Greek words θύσανος, thysanos, "tassel or fringe", and πτερόν, pteron, "wing", with reference to the insects' fringed wings.[8][9][10]

Morphology

[edit]

Thrips are small hemimetabolic insects with a distinctive cigar-shaped body plan.[11] They are elongated with transversely constricted bodies. They range in size from 0.5 to 14 mm (0.02 to 0.55 in) in length for the larger predatory thrips, but most thrips are about 1 mm in length. Flight-capable thrips have two similar, strap-like pairs of wings with a fringe of bristles. The wings are folded back over the body at rest. Their legs usually end in two tarsal segments with a bladder-like structure known as an "arolium" at the pretarsus. This structure can be everted by means of hemolymph pressure, enabling the insect to walk on vertical surfaces.[12][13] They have compound eyes consisting of a small number of ommatidia and three ocelli or simple eyes on the head.[14]

Thrips have asymmetrical mouthparts unique to the group. Unlike the Hemiptera (true bugs), the right mandible of thrips is reduced and vestigial – and in some species completely absent.[15] The left mandible is used briefly to cut into the food plant; saliva is injected and the maxillary stylets, which form a tube, are then inserted and the semi-digested food pumped from ruptured cells. This process leaves cells destroyed or collapsed, and a distinctive silvery or bronze scarring on the surfaces of the stems or leaves where the thrips have fed.[16] The mouthparts of thrips have been described as “rasping-sucking”,[17] “punching and sucking”,[11] or, simply just a specific type of “piercing-sucking” mouthparts.[18]

Thysanoptera is divided into two suborders, Terebrantia and Tubulifera; these can be distinguished by morphological, behavioral, and developmental characteristics. Tubulifera consists of a single family, Phlaeothripidae; members can be identified by their characteristic tube-shaped apical abdominal segment, egg-laying atop the surface of leaves, and three "pupal" stages. In the Phlaeothripidae, the males are often larger than females and a range of sizes may be found within a population. The largest recorded phlaeothripid species is about 14 mm long. Females of the eight families of the Terebrantia all possess the eponymous saw-like (see terebra) ovipositor on the anteapical abdominal segment, lay eggs singly within plant tissue, and have two "pupal" stages. In most Terebrantia, the males are smaller than females. The family Uzelothripidae has a single species and it is unique in having a whip-like terminal antennal segment.[14]

Evolution

[edit]

The earliest fossils of thrips date back to the Permian Permothrips longipennis, although it probably not a member of this group.[19] By the Early Cretaceous, true thrips became much more abundant.[19] The extant family Merothripidae most resembles these ancestral Thysanoptera, and is probably basal to the order.[20] There are currently over six thousand species of thrips recognized, grouped into 777 extant and sixty fossil genera.[21] Some thrips were pollinators of the Ginkgoales as early as 110-105 Mya, in the Cretaceous.[22] Cenomanithrips primus,[23] Didymothrips abdominalis and Parallelothrips separatus are known from Myanmar amber of the Cenomanian age.[24]

Phylogeny

[edit]Thrips are generally considered to be the sister group to Hemiptera (bugs).[25] The phylogeny of thrips families has been little studied. A preliminary analysis in 2013 of 37 species using 3 genes, as well as a phylogeny based on ribosomal DNA and three proteins in 2012, supports the monophyly of the two suborders, Tubulifera and Terebrantia. In Terebrantia, Melanothripidae may be sister to all other families, but other relationships remain unclear. In Tubulifera, the Phlaeothripidae and its subfamily Idolothripinae are monophyletic. The two largest thrips subfamilies, Phlaeothripinae and Thripinae, are paraphyletic and need further work to determine their structure. The internal relationships from these analyses are shown in the cladogram.[26][27]

| Thysanoptera |

| ||||||||||||

Taxonomy

[edit]The following families are (2013) recognized:[27][28][14]

- Suborder Terebrantia

Adult Franklinothrips vespiformis (Aeolothripidae), a widely distributed tropical species

- Adiheterothripidae Shumsher, 1946 (11 genera)

- Aeolothripidae Uzel, 1895 (29 genera) – banded thrips and broad-winged thrips

- Fauriellidae Priesner, 1949 (four genera)

- †Hemithripidae Bagnall, 1923 (one fossil genus, Hemithrips with 15 species)

- Heterothripidae Bagnall, 1912 (seven genera, restricted to the New World)

- †Jezzinothripidae zur Strassen, 1973 (included by some authors in Merothripidae)

- †Karataothripidae Sharov, 1972 (one fossil species, Karataothrips jurassicus)

- Melanthripidae Bagnall, 1913 (six genera of flower feeders)

- Merothripidae Hood, 1914 (five genera, mostly Neotropical and feeding on dry-wood fungi) – large-legged thrips

- †Scudderothripidae zur Strassen, 1973 (included by some authors in Stenurothripidae)

- Thripidae Stephens, 1829 (292 genera in four subfamilies, flower living) – common thrips

- †Triassothripidae Grimaldi & Shmakov, 2004 (two fossil genera)

- Uzelothripidae Hood, 1952 (one species, Uzelothrips scabrosus)

- Suborder Tubulifera

- Phlaeothripidae Uzel, 1895 (447 genera in two subfamilies, fungal hyphae and spore feeders)

The identification of thrips to species is challenging as types are maintained as slide preparations of varying quality over time. There is also considerable variability leading to many species being misidentified. Molecular sequence based approaches have increasingly been applied to their identification.[29][30]

Biology

[edit]

Feeding

[edit]Thrips are believed to have descended from a fungus-feeding ancestor during the Mesozoic,[19] and many groups still feed upon and inadvertently redistribute fungal spores.[31] These live among leaf litter or on dead wood and are important members of the ecosystem, their diet often being supplemented with pollen. Other species are primitively eusocial and form plant galls and still others are predatory on mites and other thrips.[9][32] Two species of Aulacothrips, A. tenuis and A. levinotus, have been found to be ectoparasites on aetalionid and membracid plant-hoppers in Brazil.[33] Akainothrips francisi of Australia is a parasite within the colonies of another thrips species Dunatothrips aneurae that makes silken nests or domiciles on Acacia trees.[34] A number of thrips in the subfamily Phlaeothripinae that specialize on Acacia hosts produce silk with which they glue together phyllodes to form domiciles inside which their semi-social colonies live.[35]

Mirothrips arbiter has been found in paper wasp nests in Brazil. The eggs of the hosts including Mischocyttarus atramentarius, Mischocyttarus cassununga and Polistes versicolor are eaten by the thrips.[36] Thrips, especially in the family Aeolothripidae, are also predators, and are considered beneficial in the management of pests like the codling moths.[37]

Most research has focused on thrips species that feed on economically significant crops. Some species are predatory, but most of them feed on pollen and the chloroplasts harvested from the outer layer of plant epidermal and mesophyll cells. They prefer tender parts of the plant, such as buds, flowers and new leaves.[38][39] Besides feeding on plant tissues, the common blossom thrips feeds on pollen grains and on the eggs of mites. When the larva supplements its diet in this way, its development time and mortality is reduced, and adult females that consume mite eggs increase their fecundity and longevity.[40]

Pollination

[edit]

Some flower-feeding thrips pollinate the flowers they are feeding on,[41] and some authors suspect that they may have been among the first insects to evolve a pollinating relationship with their host plants.[42] Amber fossils of Gymnopollisthrips from the Early Cretaceous show them to be coated in Cycadopites-like pollen.[43] Scirtothrips dorsalis carries pollen of commercially important chili peppers.[44][45][46] Darwin found that thrips could not be kept out by any netting when he conducted experiments by keeping away larger pollinators.[47]Thrips setipennis is the sole pollinator of Wilkiea huegeliana, a small, unisexual annually flowering tree or shrub in the rainforests of eastern Australia. T. setipennis serves as an obligate pollinator for other Australian rainforest plant species, including Myrsine howittiana and M. variabilis.[48] The genus Cycadothrips is a specialist pollinator of cycads, which are normally wind pollinated but some species of Macrozamia are able to attract thrips to male cones at some times and repel them so that they move to female cones.[49] Thrips are likewise the primary pollinators of heathers in the family Ericaceae,[50] and play a significant role in the pollination of pointleaf manzanita. Electron microscopy has shown thrips carrying pollen grains adhering to their backs, and their fringed wings are perfectly capable of allowing them to fly from plant to plant.[49]

Damage to plants

[edit]Thrips can cause damage during feeding.[51] This impact may fall across a broad selection of prey items, as there is considerable breadth in host affinity across the order, and even within a species, varying degrees of fidelity to a host.[38][52] Family Thripidae in particular is notorious for members with broad host ranges, and the majority of pest thrips come from this family.[53][54][55] For example, Thrips tabaci damages crops of onions, potatoes, tobacco, and cotton.[39][56]

Some species of thrips create galls, almost always in leaf tissue. These may occur as curls, rolls or folds, or as alterations to the expansion of tissues causing distortion to leaf blades. More complex examples cause rosettes, pouches and horns. Most of these species occur in the tropics and sub-tropics, and the structures of the galls are diagnostic of the species involved.[57] A radiation of thrips species seems to have taken place on Acacia trees in Australia; some of these species cause galls in the petioles, sometimes fixing two leaf stalks together, while other species live in every available crevice in the bark. In Casuarina in the same country, some species have invaded stems, creating long-lasting woody galls.[58]

Social behaviour

[edit]While poorly documented, chemical communication is believed to be important to the group.[59] Anal secretions are produced in the hindgut,[60] and released along the posterior setae as predator deterrents[60][61] In Australia, aggregations of male common blossom thrips have been observed on the petals of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis and Gossypium hirsutum; females were attracted to these groups so it seems likely that the males were producing pheromones.[62]

In the phlaeothripids that feed on fungi, males compete to protect and mate with females, and then defend the egg-mass. Males fight by flicking their rivals away with their abdomen, and may kill with their foretarsal teeth. Small males may sneak in to mate while the larger males are busy fighting. In the Merothripidae and in the Aeolothripidae, males are again polymorphic with large and small forms, and probably also compete for mates, so the strategy may well be ancestral among the Thysanoptera.[14]

Many thrips form galls on plants when feeding or laying their eggs. Some of the gall-forming Phlaeothripidae, such as genera Kladothrips[63] and Oncothrips,[64] form eusocial groups similar to ant colonies, with reproductive queens and nonreproductive soldier castes.[65][66][67]

Flight

[edit]Most insects create lift by the stiff-winged mechanism of insect flight with steady state aerodynamics; this creates a leading edge vortex continuously as the wing moves. The feathery wings of thrips, however, generate lift by clap and fling, a mechanism discovered by the Danish zoologist Torkel Weis-Fogh in 1973. In the clap part of the cycle, the wings approach each other over the insect's back, creating a circulation of air which sets up vortices and generates useful forces on the wings. The leading edges of the wings touch, and the wings rotate around their leading edges, bringing them together in the "clap". The wings close, expelling air from between them, giving more useful thrust. The wings rotate around their trailing edges to begin the "fling", creating useful forces. The leading edges move apart, making air rush in between them and setting up new vortices, generating more force on the wings. The trailing edge vortices, however, cancel each other out with opposing flows. Weis-Fogh suggested that this cancellation might help the circulation of air to grow more rapidly, by shutting down the Wagner effect which would otherwise counteract the growth of the circulation.[68][69][70][71]

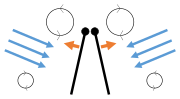

- Clap and fling flight mechanism after Sane 2003

-

Clap 1: wings close over back

-

Clap 2: leading edges touch, wing rotates around leading edge, vortices form

-

Clap 3: trailing edges close, vortices shed, wings close giving thrust

- Black circle and heavy line: wing (rachis and bristles); Black (curved) arrows: flow; Blue arrows: induced velocity; Orange arrows: net force on wing

-

Fling 1: wings rotate around trailing edge to fling apart

-

Fling 2: leading edge moves away, air rushes in, increasing lift

-

Fling 3: new vortex forms at leading edge, trailing edge vortices cancel each other, perhaps helping flow to grow faster (Weis-Fogh 1973)

Apart from active flight, thrips, even wingless ones, can also be picked up by winds and transferred long distances. During warm and humid weather, adults may climb to the tips of plants to leap and catch air current. Wind-aided dispersal of species has been recorded over 1600 km of sea between Australia and South Island of New Zealand.[14] It has been suggested that some bird species may also be involved in the dispersal of thrips. Thrips are picked up along with grass in the nests of birds and can be transported by the birds.[72]

A hazard of flight for very small insects such as thrips is the possibility of being trapped by water. Thrips have non-wetting bodies and have the ability to ascend a meniscus by arching their bodies and working their way head-first and upwards along the water surface in order to escape.[73]

Life cycle

[edit]

Scale bar is 0.5 mm

Thrips lay extremely small eggs, about 0.2 mm long. Females of the suborder Terebrantia cut slits in plant tissue with their ovipositor, and insert their eggs, one per slit. Females of the suborder Tubulifera lay their eggs singly or in small groups on the outside surfaces of plants.[74] Some thrips such as Elaphothrips tuberculatus are known to be facultatively ovoviviparous, retaining the eggs internally and giving birth to male offspring.[75] Females in many species guard the eggs against cannibalism by other females as well as predators.[76]

Thrips are hemimetabolous, metamorphosing gradually to the adult form. The first two instars, called larvae or nymphs, are like small wingless adults (often confused with springtails) without genitalia; these feed on plant tissue. In the Terebrantia, the third and fourth instars, and in the Tubulifera also a fifth instar, are non-feeding resting stages similar to pupae: in these stages, the body's organs are reshaped, and wing-buds and genitalia are formed.[74] The larvae of some species produce silk from the terminal abdominal segment which is used to line the cell or form a cocoon within which they pupate.[77] The adult stage can be reached in around 8–15 days; adults can live for around 45 days.[78] Adults have both winged and wingless forms; in the grass thrips Anaphothrips obscurus, for example, the winged form makes up 90% of the population in spring (in temperate zones), while the wingless form makes up 98% of the population late in the summer.[79] Thrips can survive the winter as adults or through egg or pupal diapause.[14]

Thrips are haplodiploid with haploid males (from unfertilised eggs, as in Hymenoptera) and diploid females capable of parthenogenesis (reproducing without fertilisation), many species using arrhenotoky, a few using thelytoky.[80] In Pezothrips kellyanus females hatch from larger eggs than males, possibly because they are more likely to be fertilized.[81] The sex-determining bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia is a factor that affects the reproductive mode.[52][80][82] Several normally bisexual species have become established in the United States with only females present.[80][83]

Human impact

[edit]

As pests

[edit]

Many thrips are pests of commercial crops due to the damage they cause by feeding on developing flowers or vegetables, causing discoloration, deformities, and reduced marketability of the crop. Some thrips serve as vectors for plant diseases, such as tospoviruses.[84] Over 20 plant-infecting viruses are known to be transmitted by thrips, but perversely, less than a dozen of the described species are known to vector tospoviruses.[85] These enveloped viruses are considered among some of the most damaging of emerging plant pathogens around the world, with those vector species having an outsized impact on human agriculture. Virus members include the tomato spotted wilt virus and the impatiens necrotic spot viruses. The western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis, has spread until it now has a worldwide distribution, and is the primary vector of plant diseases caused by tospoviruses.[86] Other viruses that they spread include the genera Ilarvirus, (Alpha |Beta |Gamma)carmovirus, Sobemovirus and Machlomovirus.[87] Their small size and predisposition towards enclosed places makes them difficult to detect by phytosanitary inspection, while their eggs, laid inside plant tissue, are well-protected from pesticide sprays.[78] When coupled with the increasing globalization of trade and the growth of greenhouse agriculture, thrips, unsurprisingly, are among the fastest growing group of invasive species in the world. Examples include F. occidentalis, Thrips simplex, and Thrips palmi.[88]

Flower-feeding thrips are routinely attracted to bright floral colors (including white, blue, and especially yellow), and will land and attempt to feed. It is not uncommon for some species (e.g., Frankliniella tritici and Limothrips cerealium) to "bite" humans under such circumstances. Although no species feed on blood and no known animal disease is transmitted by thrips, some skin irritation has been described.[89]

Management

[edit]

Thrips develop resistance to insecticides easily and there is constant research on how to control them. This makes thrips ideal as models for testing the effectiveness of new pesticides and methods.[90]

Due to their small sizes and high rates of reproduction, thrips are difficult to control using classical biological control. Suitable predators must be small and slender enough to penetrate the crevices where thrips hide while feeding, and they must also prey extensively on eggs and larvae to be effective. Only two families of parasitoid Hymenoptera parasitize eggs and larvae, the Eulophidae and the Trichogrammatidae. Other biocontrol agents of adults and larvae include anthocorid bugs of genus Orius, and phytoseiid mites. Biological insecticides such as the fungi Beauveria bassiana and Verticillium lecanii can kill thrips at all life-cycle stages.[91] Insecticidal soap spray is effective against thrips. It is commercially available or can be made of certain types of household soap. Scientists in Japan report that significant reductions in larva and adult melon thrips occur when plants are illuminated with red light.[92]

References

[edit]- ^ Fedor, Peter J.; Doricova, Martina; Prokop, Pavol; Mound, Laurence A. (2010). "Heinrich Uzel, the father of Thysanoptera studies" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2645: 55–63. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2645.1.3.

- ^ Uzel, Jindrich (1895). Monografie řádu Thysanoptera. Hradec Králové.

- ^ Fedor, Peter J.; Doricova, Martina; Prokop, Pavol; Mound, Laurence A. (2010). "Heinrich Uzel, the father of Thysanoptera studies" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2645: 55–63. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2645.1.3.

Jindřich (Heinrich) Uzel, a Czech phytopathologist and entomologist, published in 1895 a monograph on the Order Thysanoptera that provided the basis for almost all subsequent work on this group of insects.

- ^ θρίψ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Kobro, Sverre (2011). "Checklist of Nordic Thysanoptera" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 58: 21–26. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ^ Kirk, W.D.J. (1996). Thrips: Naturalists' Handbooks 25. The Richmond Publishing Company.

- ^ Marren, Peter; Mabey, Richard (2010). Bugs Britannica. Chatto & Windus. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ^ "Thysanoptera". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b Tipping, C. (2008). Capinera, John L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 3769–3771. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ θύσανος, πτερόν in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ a b "Biology and Management of Thrips Affecting the Production Nursery and Landscape". University of Georgia. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Gillott, Cedric (2005). Entomology. Springer. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-306-44967-3.

- ^ Heming, B. S. (1971). "Functional morphology of the thysanopteran pretarsus". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 49 (1): 91–108. doi:10.1139/z71-014. PMID 5543183.

- ^ a b c d e f Mound, L.A. (2003). "Thysanoptera". In Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 999–1003. ISBN 978-0-12-586990-4.

- ^ Childers, C.C.; Achor, D.S. (1989). "Structure of the mouthparts of Frankliniella bispinosa (Morgan) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae).". In Parker, B.L.; Skinner, M.; Lewis, T. (eds.). Towards Understanding Thysanoptera. Proceedings of the International Conference on Thrips. Radnor, PA: USDA Technical Report NE-147.

- ^ Chisholm, I.F.; Lewis, T. (2009). "A new look at thrips (Thysanoptera) mouthparts, their action and effects of feeding on plant tissue". Bulletin of Entomological Research. 74 (4): 663–675. doi:10.1017/S0007485300014048.

- ^ "Thrips: Biology and Rose Pests". North Carlolina State University. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ "Thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)" (PDF). Colorado State University.

- ^ a b c Grimaldi, D.; Shmakov, A.; Fraser, N. (2004). "Mesozoic Thrips and Early Evolution of the Order Thysanoptera (Insecta)". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (5): 941–952. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0941:mtaeeo>2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4094919. S2CID 85901347.

- ^ Mound, L.A. (1997). "Thrips as Crop Pests". In Lewis, T. (ed.). Biological diversity. CAB International. pp. 197–215.

- ^ "Thrips Wiki". Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Peñalver, Enrique; Labandeira, Conrad C.; Barrón, Eduardo; et al. (21 May 2012). "Thrips pollination of Mesozoic gymnosperms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (22): 8623–8628. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120499109. PMC 3365147. PMID 22615414.

- ^ Tong, Tingting; Shih, Chungkun; Ren, Dong (2019). "A new genus and species of Stenurothripidae (Insecta: Thysanoptera: Terebrantia) from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber". Cretaceous Research. 100. Elsevier BV: 184–191. Bibcode:2019CrRes.100..184T. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.03.005. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Guo, Dawei; Engel, Michael S.; Shih, Chungkun; Ren, Dong (21 February 2024). "New stenurothripid thrips from mid-Cretaceous Kachin amber (Thysanoptera, Stenurothripidae)". ZooKeys (1192). Pensoft Publishers: 197–212. doi:10.3897/zookeys.1192.117754. PMC 10902785. PMID 38425444.

- ^ Li, Hu; et al. (2015). "Higher-level phylogeny of paraneopteran insects inferred from mitochondrial genome sequences". Scientific Reports. 5: 8527. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5.8527L. doi:10.1038/srep08527. PMC 4336943. PMID 25704094.

- ^ Terry, Mark; Whiting, Michael (2013). "Evolution of Thrips (Thysanoptera) Phylogenetic Patterns and Mitochondrial Genome Evolution". Journal of Undergraduate Research.

- ^ a b Buckman, Rebecca S.; Mound, Laurence A.; Whiting, Michael F. (2012). "Phylogeny of thrips (Insecta: Thysanoptera) based on five molecular loci". Systematic Entomology. 38 (1): 123–133. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2012.00650.x. S2CID 84909610.

- ^ Mound, L.A. (2011). "Order Thysanoptera Haliday, 1836 in Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 201–202. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.38.

- ^ Mound, Laurence A. (2013). "Homologies and Host-Plant Specificity: Recurrent Problems in the Study of Thrips". Florida Entomologist. 96 (2): 318–322. doi:10.1653/024.096.0250.

- ^ Rugman-Jones, Paul F.; Hoddle, Mark S.; Mound, Laurence A.; Stouthamer, Richard (2006). "Molecular Identification Key for Pest Species of Scirtothrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)". J. Econ. Entomol. 99 (5): 1813–1819. doi:10.1093/jee/99.5.1813. PMID 17066817.

- ^ Morse, Joseph G.; Hoddle, Mark S. (2006). "Invasion Biology of Thrips". Annual Review of Entomology. 51: 67–89. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151044. PMID 16332204.

- ^ Wang, Zhaohong; Mound, Laurence A.; Hussain, Mubasher; Arthurs, Steven P.; Mao, Runqian (2022). "Thysanoptera as predators: Their diversity and significance as biological control agents". Pest Management Science. 78 (12): 5057–5070. doi:10.1002/ps.7176. PMID 36087293. S2CID 252181342.

- ^ Cavalleri, Adriano; Kaminski, Lucas A. (2014). "Two new ectoparasitic species of Aulacothrips Hood, 1952 (Thysanoptera: Heterothripidae) associated with ant-tended treehoppers (Hemiptera)". Systematic Parasitology. 89 (3): 271–8. doi:10.1007/s11230-014-9526-z. PMID 25274260. S2CID 403014.

- ^ Gilbert, James D. J.; Mound, Laurence A.; Simpson, Stephen J. (2012). "Biology of a new species of socially parasitic thrips (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) inside Dunatothrips nests, with evolutionary implications for inquilinism in thrips: A NEW INQUILINE THRIPS". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 107 (1): 112–122. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.01928.x.

- ^ Gilbert, James D. J.; Simpson, Stephen J. (2013). "Natural history and behaviour of Dunatothrips aneurae Mound (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae), a phyllode-gluing thrips with facultative pleometrosis: Natural History of Dunatothrips aneurae". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (4): 802–816. doi:10.1111/bij.12100.

- ^ Cavalleri, Adriano; De Souza, André R.; Prezoto, Fábio; Mound, Laurence A. (2013). "Egg predation within the nests of social wasps: a new genus and species of Phlaeothripidae, and evolutionary consequences of Thysanoptera invasive behaviour". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (2): 332–341. doi:10.1111/bij.12057.

- ^ Tadic, M. (1957). The Biology of the Codling Moth as the Basis for Its Control. Univerzitet U Beogradu.

- ^ a b Kirk, W.D.J. (1995). "Feeding behavior and nutritional requirements". In Parker, B.L.; Skinner, M.; Lewis, T. (eds.). Thrips Biology and Management. Plenum Press. pp. 21–29.

- ^ a b "Onion Thrips". NCSU. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ Milne, M.; Walter, G.H. (1997). "The significance of prey in the diet of the phytophagous thrips, Frankliniella schultzei". Ecological Entomology. 22 (1): 74–81. Bibcode:1997EcoEn..22...74M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.1997.00034.x. S2CID 221682518.

- ^ Terry, I.; Walter, G.H.; Moore, C.; Roemer, R.; Hull, C. (2007). "Odor-Mediated Push-Pull Pollination in Cycads". Science. 318 (5847): 70. Bibcode:2007Sci...318...70T. doi:10.1126/science.1145147. PMID 17916726. S2CID 24147411.

- ^ Terry, I. (2001). "Thrips: the primeval pollinators?". Thrips and Tospoviruses: Proceedings of the 7th Annual Symposium on Thysanoptera: 157–162.

- ^ Peñalver, Enrique; Labandeira, Conrad C.; Barrón, Eduardo; Delclòs, Xavier; Nel, Patricia; Nel, André; Tafforeau, Paul; Soriano, Carmen (2012). "Thrips pollination of Mesozoic gymnosperms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (22): 8623–8628. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120499109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3365147. PMID 22615414.

- ^ Sakai, S. (2001). "Thrips pollination of androdioecious Castilla elastica (Moraceae) in a seasonal tropical forest". American Journal of Botany. 88 (9): 1527–1534. doi:10.2307/3558396. JSTOR 3558396. PMID 21669685.

- ^ Saxena, P.; Vijayaraghavan, M.R.; Sarbhoy, R.K.; Raizada, U. (1996). "Pollination and gene flow in chillies with Scirtothrips dorsalis as pollen vectors". Phytomorphology. 46: 317–327.

- ^ Frame, Dawn (2003). "Generalist flowers, biodiversity and florivory: implications for angiosperm origins". Taxon. 52 (4): 681–5. doi:10.2307/3647343. JSTOR 3647343.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1892). The effects of cross and self fertilization in the vegetable kingdom. D. Appleton & Company. p. 11.

- ^ Williams, G.A.; Adam, P.; Mound, L.A. (2001). "Thrips (Thysanoptera) pollination in Australian subtropical rainforests, with particular reference to pollination of Wilkiea huegeliana (Monimiaceae)". Journal of Natural History. 35 (1): 1–21. Bibcode:2001JNatH..35....1W. doi:10.1080/002229301447853. S2CID 216092358.

- ^ a b Eliyahu, Dorit; McCall, Andrew C.; Lauck, Marina; Trakhtenbrot, Ana; Bronstein, Judith L. (2015). "Minute pollinators: The role of thrips (Thysanoptera) as pollinators of pointleaf manzanita, Arctostaphylos pungens (Ericaceae)". Journal of Pollination Ecology. 16: 64–71. doi:10.26786/1920-7603(2015)10. PMC 4509684. PMID 26207155.

- ^ García-Fayos, Patricio; Goldarazena, Arturo (2008). "The role of thrips in pollination of Arctostaphyllos uva-ursi". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 169 (6): 776–781. doi:10.1086/588068. S2CID 58888285.

- ^ Childers, C.C. (1997). "Feeding and oviposition injuries to plants". In Lewis, T. (ed.). Thrips as Crop Pests. CAB International. pp. 505–538.

- ^ a b Mound, L.A. (2005). "Thysanoptera: diversity and interactions". Annual Review of Entomology. 50: 247–269. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123318. PMID 15355240.

- ^ Bailey, S.F. (1940). "The distribution of injurious thrips in the United States". Journal of Economic Entomology. 33 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1093/jee/33.1.133.

- ^ Ananthakrishnan, T.N. (1993). "Bionomics of Thrips". Annual Review of Entomology. 38: 71–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.38.010193.000443.

- ^ Mound, Laurence A.; Wang, Zhaohong; Lima, Élison F. B.; Marullo, Rita (2022). "Problems with the Concept of "Pest" among the Diversity of Pestiferous Thrips". Insects. 13 (1): 61. doi:10.3390/insects13010061. PMC 8780980. PMID 35055903.

- ^ "Thrips tabaci (onion thrips)". Invasive Species Compendium. CABI. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Jorge, Nina Castro; Cavalleri, Adriano; Bedetti, Cibele Souza; Isaias, Rosy Mary Dos Santos (2016). "A new leaf-galling Holopothrips (Thysanoptera: Phlaeothripidae) and the structural alterations on Myrcia retorta (Myrtaceae)". Zootaxa. 4200 (1): 174–180. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4200.1.8. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 27988645.

- ^ Mound, Laurence A. (2014). "Austral Thysanoptera: 100 years of progress". Australian Journal of Entomology. 53 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1111/aen.12054. S2CID 85793869.

- ^ Blum, M.S. (1991). Parker, B.L.; Skinner, M.; Lewis, T. (eds.). "Towards understanding Thysanoptera: Chemical ecology of the Thysanoptera". Proceedings of the International Conference on Thrips. USDA Technical Report NE-147: 95–108.

- ^ a b Howard, Dennis F.; Blum, Murray S.; Fales, Henry M. (1983). "Defense in Thrips: Forbidding Fruitiness of a Lactone". Science. 220 (4594): 335–336. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..335H. doi:10.1126/science.220.4594.335. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17732921. S2CID 24856539.

- ^ Tschuch, G.; Lindemann, P.; Moritz, G. (2002). Mound, L.A.; Marullo, R. (eds.). "Chemical defence in thrips". Thrips and Tospoviruses: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Thysanoptera: 277–278.

- ^ Milne, M.; Walter, G.H.; Milne, J.R. (2002). "Mating Aggregations and Mating Success in the Flower Thrips, Frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and a Possible Role for Pheromones". Journal of Insect Behavior. 15 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1023/A:1016265109231. S2CID 23545048.

- ^ Kranz, B.D.; Schwarz, M.P.; Mound, L.A.; Crespi, B.J. (1999). "Social biology and sex ratios of the eusocial gall-inducing thrips Kladothrips hamiltoni". Ecological Entomology. 24 (4): 432–442. Bibcode:1999EcoEn..24..432K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.1999.00207.x. S2CID 83180900.

- ^ Kranz, Brenda D.; Schwarz, Michael P.; Wills, Taryn E.; Chapman, Thomas W.; Morris, David C.; Crespi, Bernard J. (2001). "A fully reproductive fighting morph in a soldier clade of gall-inducing thrips (Oncothrips morrisi)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 50 (2): 151–161. doi:10.1007/s002650100347. JSTOR 4601948. S2CID 38152512.

- ^ Crespi, B.J.; Mound, L.A. (1997). "Ecology and evolution of social behaviour among Australian gall thrips and their allies". In Choe, J.C.; Crespi, B.J. (eds.). The evolution of social behaviour of insects and arachnids. Cambridge University Press. pp. 166–180. ISBN 978-0-521-58977-2.

- ^ Chapman, T.W.; Crespi, B.J. (1998). "High relatedness and inbreeding in two species of haplodiploid eusocial thrips (Insecta: Thysanoptera) revealed by microsatellite analysis". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 43 (4): 301–306. doi:10.1007/s002650050495. JSTOR 4601521. S2CID 32909187.

- ^ Kranz, Brenda D.; Schwarz, Michael P.; Morris, David C.; Crespi, Bernard J. (2002). "Life history of Kladothrips ellobus and Oncothrips rodwayi: insight into the origin and loss of soldiers in gall-inducing thrips". Ecological Entomology. 27 (1): 49–57. Bibcode:2002EcoEn..27...49K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2311.2002.0380a.x. S2CID 85097661.

- ^ Weis-Fogh, Torkel (1973). "Quick estimates of flight fitness in hovering animals, including novel mechanisms for lift production". Journal of Experimental Biology. 59: 169–230. doi:10.1242/jeb.59.1.169.

- ^ Sane, Sanjay P. (2003). "The aerodynamics of insect flight" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 206 (23): 4191–4208. doi:10.1242/jeb.00663. PMID 14581590. S2CID 17453426.

- ^ Wang, Z. Jane (2005). "Dissecting Insect Flight" (PDF). Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 37 (1): 183–210. Bibcode:2005AnRFM..37..183W. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.121940.

- ^ Lighthill, M.J. (1973). "On the Weis-Fogh mechanism of lift generation". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 60: 1–17. Bibcode:1973JFM....60....1L. doi:10.1017/s0022112073000017. S2CID 123051925.

- ^ Fedor, Peter; Doričová, Martina; Dubovský, Michal; Kisel'ák, Jozef; Zvarík, Milan (15 August 2019). "Cereal pests among nest parasites – the story of barley thrips, Limothrips denticornis Haliday (Thysanoptera: Thripidae)". Entomologica Fennica. 21 (4): 221–231. doi:10.33338/ef.84532. ISSN 2489-4966. S2CID 82549305.

- ^ Ortega-Jiménez, Victor Manuel; Arriaga-Ramirez, Sarahi; Dudley, Robert (2016). "Meniscus ascent by thrips (Thysanoptera)". Biology Letters. 12 (9): 20160279. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0279. PMC 5046919. PMID 27624795.

- ^ a b Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P.S. (2010). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 511. ISBN 978-1-118-84615-5.

- ^ Crespi, Bernard J. (1989). "Facultative viviparity in a thrips". Nature. 337 (6205): 357–358. doi:10.1038/337357a0. hdl:2027.42/62912. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Crespi, Bernard J. (1990). "Subsociality and female reproductive success in a mycophagous thrips: An observational and experimental analysis". Journal of Insect Behavior. 3 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1007/BF01049195. hdl:2027.42/44947. ISSN 0892-7553.

- ^ Conti, Barbara; Berti, Francesco; Mercati, David; Giusti, Fabiola; Dallai, Romano (2009). "The ultrastructure of malpighian tubules and the chemical composition of the cocoon of Aeolothrips intermedius Bagnall (Thysanoptera)". Journal of Morphology. 271 (2): 244–254. doi:10.1002/jmor.10793. PMID 19725134. S2CID 40887930.

- ^ a b Smith, Tina M. (2015). "Western Flower Thrips, Management and Tospoviruses". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Capinera, John L. (2001). Handbook of Vegetable Pests. Gulf. p. 538. ISBN 978-0-12-158861-8.

- ^ a b c van der Kooi, C.J.; Schwander, T. (2014). "Evolution of asexuality via different mechanisms in grass thrips (Thysanoptera: Aptinothrips)" (PDF). Evolution. 68 (7): 1883–1893. doi:10.1111/evo.12402. PMID 24627993. S2CID 14853526.

- ^ Katlav, Alihan; Cook, James M.; Riegler, Markus (2020). Houslay, Thomas (ed.). "Egg size-mediated sex allocation and mating-regulated reproductive investment in a haplodiploid thrips species". Functional Ecology. 35 (2): 485–498. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13724. ISSN 0269-8463. S2CID 229397678.

- ^ Kumm, S.; Moritz, G. (2008). "First detection of Wolbachia in arrhenotokous populations of thrips species (Thysanoptera: Thripidae and Phlaeothripidae) and its role in reproduction". Environmental Entomology. 37 (6): 1422–8. doi:10.1603/0046-225X-37.6.1422. PMID 19161685. S2CID 22128201.

- ^ Stannard, L.J. (1968). "The thrips, or Thysanoptera, of Illinois". Illinois Natural History Survey. 21 (1–4): 215–552. doi:10.21900/j.inhs.v29.166.

- ^ Nault, L.R. (1997). "Arthropod transmission of plant viruses: a new synthesis". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 90 (5): 521–541. doi:10.1093/aesa/90.5.521.

- ^ Mound, L.A. (2001). "So many thrips – so few tospoviruses?". Thrips and Tospoviruses: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Thysanoptera: 15–18.

- ^ Morse, Joseph G.; Hoddle, Mark S. (2006). "Invasion Biology of Thrips". Annual Review of Entomology. 51: 67–89. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151044. PMID 16332204. S2CID 14430622.

- ^ Jones, David R (2005). "Plant Viruses Transmitted by Thrips". European Journal of Plant Pathology. 113 (2): 119–157. Bibcode:2005EJPP..113..119J. doi:10.1007/s10658-005-2334-1. ISSN 0929-1873. S2CID 6412752.

- ^ Carlton, James (2003). Invasive Species: Vectors And Management Strategies. Island Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-61091-153-5.

- ^ Childers, C.C.; Beshear, R.J.; Frantz, G.; Nelms, M. (2005). "A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986–1997". Florida Entomologist. 88 (4): 447–451. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2005)88[447:AROTSB]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Kivett, Jessica M.; Cloyd, Raymond A.; Bello, Nora M. (2015). "Insecticide rotation programs with entomopathogenic organisms for suppression of western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) adult populations under greenhouse conditions". Journal of Economic Entomology. 108 (4): 1936–1946. doi:10.1093/jee/tov155. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 26470338. S2CID 205163917.

- ^ Hoddle, Mark. "Western flower thrips in greenhouses: a review of its biological control and other methods". University of California, Riverside. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Katai, Yusuke; Ishikawa, Ryusuke; Doi, Makoto; Masui, Shinichi (2015). "Efficacy of red LED irradiation for controlling Thrips palmi in greenhouse melon cultivation". Japanese Journal of Applied Entomology and Zoology. 59 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1303/jjaez.2015.1.

KSF

KSF