Tilpin

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 7 min

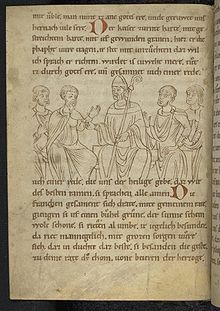

Tilpin, Latin Tilpinus (died 794 or 800), also called Tulpin,[1] a name later corrupted as Turpin, was the bishop of Reims from about 748 until his death. He was for many years regarded as the author of the legendary Historia Caroli Magni, which is thus also known as the "Pseudo-Turpin Chronicle". He appears as one of the Twelve Peers of France in a number of the chansons de geste,[2] the most important of which is the Song of Roland. His portrayal in the chansons, often as a warrior-bishop, is fictitious.

According to Flodoard, the tenth-century historian of the church of Reims, Tilpin was originally a monk at the Basilica of Saint-Denis near Paris.[2] He may have served as a chorbishop under Bishop Milo of Trier (who was also acting as bishop of Reims) before becoming full bishop upon Milo's death around 762.[3] The date of Tilpin's election as a bishop is unknown, usually placed in 748 or 753. According to Hincmar, the later archbishop of Reims, Tilpin occupied himself in securing the restoration of the rights and properties of his church, the revenues and prestige of which had been impaired under the rule of the more martial Milo.[2]

Before Tilpin's episcopate, probably no earlier than 745, a community of priests had formed in the 6th-century basilica that housed the relics of Saint Remigius. Tilpin gave this community a monastic rule and thus founded the abbey of Saint-Rémi (now the Musée Saint-Remi.[4] He is also credited with founding the scriptorium and library of Reims Cathedral.[3] In 769, Tilpin was one of twelve Frankish bishops to attend the synod of Rome.[5]

In 771, Carloman I, joint king of the Franks with his brother, was buried in a 4th-century Roman sarcophagus in the abbey of Saint-Remi in Reims. Tilpin presumably performed the funeral. As a result, the city of Reims was neglected during the long reign of Carloman's brother and rival, Charlemagne. Despite the apparent coolness between Tilpin and Charlemagne, the latter did confirm several of his brother's donations to Saint-Remi.[6]

There is a letter purportedly sent by Pope Adrian I to Tilpin in 780, in which the pope recalls how Charlemagne had asked him to send Tilpin the pallium (thus making him an archbishop in 779) and how Charlemagne and Carloman had restored many lands that had previously been taken from the church of Reims. Modern scholarship has tended to view this letter as being heavily interpolated by later partisans of the see of Reims, either by Archbishop Hincmar or by supporters of the deposed archbishop, Ebbo. Another letter, sent by Hincmar to King Louis the Younger, claims that Tilpin granted the villa of Douzy to Charlemagne as a precarium in exchange for the nona et decima and twelve pounds of silver annually. This letter, too, has come under suspicion as falsified.[6]

Tilpin died in 794, if the evidence of a diploma alluded to by Jean Mabillon may be trusted, although it has been stated that this event took place on 2 September 800. Hincmar, who composed his epitaph, makes him bishop for over forty years, while Flodoard says that he died in the forty-seventh year of his archbishopric. The Historia de vita Caroli magni et Rolandi, attributed to Tilpin, was declared authentic in 1122 by Pope Callixtus II. It is, however, entirely legendary, being instead the crystallization of earlier Roland legends than the source of later ones, and its popularity seems to date from the latter part of the 12th century.[2]

It is possible that the warlike legends which have gathered around the name of "Turpin" are due to some confusion of his identity with that of his predecessor Milo. According to Flodoard, Charles Martel drove Archbishop Rigobert from his office and replaced him with a warrior clerk named Milo, afterwards also bishop of Trier. Flodoard also represents Milo as discharging a mission among the Vascones (the ancestors of the Basques), the same people credited with ambushing the rearguard of Charlemagne's army and killing Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778.[2]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dahn 1894.

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b Bauer 1997, p. 728.

- ^ Glenn 2004, pp. 70–71.

- ^ McKitterick 2008, p. 83.

- ^ a b Nelson 2000, pp. 151–52.

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Turpin of Rheims". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 482.

- Bauer, Thomas (1997). "Turpin von Reims". Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon. Vol. 12. Herzberg: Bautz. pp. 727–31.

- Dahn, Felix (1894). "Tilpin". Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Vol. 38. p. 351.

- Glenn, Jason (2004). Politics and History in the Tenth Century: The Work and World of Richer of Reims. Cambridge University Press.

- Lesne, Emile (1913). "La letter interpolée d'Adrien Ier à Tilpin". Le Moyen Âge. 26: 325–51, 389–413.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2008). Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2000). "Carolingian Royal Funerals". In Frans Theuws; Janet L. Nelson (eds.). Rituals of Power: From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Brill. pp. 131–84.

KSF

KSF