Transport in Germany

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

As a densely populated country in a central location in Europe and with a developed economy, Germany has a dense transport infrastructure.

One of the first limited-access highway systems in the world to have been built, the extensive German Autobahn network has no general speed limit for light vehicles (although there are speed limits in many sections today, and there is an 80 km/h (50 mph) limit for trucks). The country's most important waterway is the river Rhine, and largest port is that of Hamburg. Frankfurt Airport is a major international airport and European transport hub. Air travel is used for greater distances within Germany but faces competition from the state-owned Deutsche Bahn's rail network. High-speed trains called ICE connect cities for passenger travel with speeds up to 300 km/h. Many German cities have rapid transit systems and public transport is available in most areas. Buses have historically only played a marginal role in long-distance passenger service, as all routes directly competing with rail services were technically outlawed by a law dating to 1935 (during the Nazi era). Only in 2012 was this law officially amended and thus a long-distance bus market has also emerged in Germany since then.[1]

Since German reunification substantial effort has been made to improve and expand transport infrastructure in what was formerly East Germany.[2] Due to Germany's varied history, main traffic flows have changed from primarily east–west (old Prussia and the German Empire) to primarily north–south (the 1949-1990 German partition era) to a more balanced flow with both major north–south and east–west corridors, both domestically and in transit. Infrastructure, which was further hampered by the havoc wars and scorched earth policies as well as reparations wrought, had to be adjusted and upgraded with each of those shifts.

Verkehrsmittel (German: [fɛɐ̯ˈkeːɐ̯sˌmɪtl̩] ⓘ) and Verkehrszeichen - Transportation signs in Germany are available here in German and English.

Road and automotive transport

[edit]Overview

[edit]

The volume of traffic in Germany, especially goods transportation, is at a very high level due to its central location in Europe. In the past few decades, much of the freight traffic shifted from rail to road, which led the Federal Government to introduce a motor toll for trucks in 2005. Individual road usage increased resulting in a relatively high traffic density to other nations. A further increase of traffic is expected in the future. In 2023, 286 billion tonnes-kilometres are travelled by freight.[3] In 2018, 630 billion kilometers were driven by german cars. In 2023, 591 billion kilometers were driven by german cars.[4]

From 2019 to 2021, road death per billion traveled kilometres is in range 3.7 to 4.0. The Common strategy for road safety activities in Germany from 2021 to 2030 is known as the “Road Safety Pact”.[5]

In Germany urban mobility is mostly performed as a driver by car (about 58%) by urban rail or by train (about 14%) or as passenger car (12%).[6]

Germany has 229,601 kilometers of road in its road network, which make a density of 0.60 kilometer of road per square kilometer. 5.7% of those roads are known as motorways in European English[7] and eventually in British English (Autobahn).

High-speed vehicular traffic has a long tradition in Germany given that the first freeway (Autobahn) in the world, the AVUS, and the world's first automobile were developed and built in Germany. Germany possesses one of the most dense road systems of the world. German motorways have no blanket speed limit for light vehicles. However, posted limits are in place on many dangerous or congested stretches as well as where traffic noise or pollution poses a problem (20.8% under static or temporary limits and an average 2.6% under variable traffic control limit applications as of 2015).

The German government has had issues with upkeep of the country's autobahn network, having had to revamp the Eastern portion's transport system since the unification of Germany between the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). With that, numerous construction projects have been put on hold in the west, and a vigorous reconstruction has been going since the late 1990s. However, ever since the European Union formed, an overall streamlining and change of route plans have occurred as faster and more direct links to former Soviet bloc countries now exist and are in the works, with intense co-operation among European countries.

Intercity bus service within Germany fell out of favour as post-war prosperity increased, and became almost extinct when legislation was introduced in the 1980s to protect the national railway. After that market was deregulated in 2012, some 150 new intercity bus lines have been established, leading to a significant shift from rail to bus for long journeys.[8] The market has since consolidated with Flixbus controlling over 90% of it and also expanding into neighboring countries.

Roads

[edit]

Germany has approximately 650,000 km of roads,[9] of which 231,000 km are non-local roads.[10] The road network is extensively used with nearly 2 trillion km travelled by car in 2005, in comparison to just 70 billion km travelled by rail and 35 billion km travelled by plane.[9]

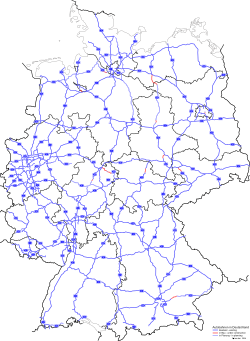

The Autobahn is the German federal highway system. The official German term is Bundesautobahn (plural Bundesautobahnen, abbreviated 'BAB'), which translates as 'federal motorway'. Where no local speed limit is posted, the advisory limit (Richtgeschwindigkeit) is 130 km/h. The Autobahn network had a total length of about 12,996 kilometres (8,075 mi) in 2016,[11] which ranks it among the most dense and longest systems in the world. Only federally built controlled-access highways meeting certain construction standards including at least two lanes per direction are called "Bundesautobahn". They have their own, blue-coloured signs and their own numbering system. All Autobahnen are named by using the capital letter A, followed by a blank and a number (for example A 8).

The main Autobahnen going all across Germany have single digit numbers. Shorter highways of regional importance have double digit numbers (like A 24, connecting Berlin and Hamburg). Very short stretches built for heavy local traffic (for example ring roads or the A 555 from Cologne to Bonn) usually have three digits, where the first digit depends on the region.

East–west routes are usually even-numbered, north–south routes are usually odd-numbered. The numbers of the north–south Autobahnen increase from west to east; that is to say, the more easterly roads are given higher numbers. Similarly, the east–west routes use increasing numbers from north to south.

The autobahns are considered the safest category of German roads: for example, in 2012, while carrying 31% of all motorized road traffic, they only accounted for 11% of Germany's traffic fatalities.[12]

German autobahns are still toll-free for light vehicles, but on 1 January 2005, a blanket mandatory toll on heavy trucks was introduced.

The national roads in Germany are called Bundesstraßen (federal roads). Their numbers are usually well known to local road users, as they appear (written in black digits on a yellow rectangle with black border) on direction traffic signs and on street maps. A Bundesstraße is often referred to as "B" followed by its number, for example "B1", one of the main east–west routes. More important routes have lower numbers. Odd numbers are usually applied to north–south oriented roads, and even numbers for east–west routes. Bypass routes are referred to with an appended "a" (alternative) or "n" (new alignment), as in "B 56n".

Other main public roads are maintained by the Bundesländer (states), called Landesstraße (country road) or Staatsstraße (state road). The numbers of these roads are prefixed with "L", "S" or "St", but are usually not seen on direction signs or written on maps. They appear on the kilometre posts on the roadside. Numbers are unique only within one state.

The Landkreise (districts) and municipalities are in charge of the minor roads and streets within villages, towns and cities. These roads have the number prefix "K" indicating a Kreisstraße.

Rail transport

[edit]Overview

[edit]

Germany features a total of 43,468 km railways, of which at least 19,973 km are electrified (2014).[13]

Deutsche Bahn (German Rail) is the major German railway infrastructure and service operator. Though Deutsche Bahn is a private company, the government still holds all shares and therefore Deutsche Bahn can still be called a state-owned company. Since its reformation under private law in 1994, Deutsche Bahn no longer publishes details of the tracks it owns; in addition to the DBAG system there are about 280 privately or locally owned railway companies which own an approximate 3,000 km to 4,000 km of the total tracks and use DB tracks in open access.

Railway subsidies amounted to €17.0 billion in 2014[14] and there are significant differences between the financing of long-distance and short-distance (or local) trains in Germany. While long-distance trains can be run by any railway company, the companies also receive no subsidies from the government. Local trains however are subsidised by the German states, which pay the operating companies to run these trains and indeed in 2013, 59% of the cost of short-distance passenger rail transport was covered by subsidies.[15] This resulted in many private companies offering to run local train services as they can provide cheaper service than the state-owned Deutsche Bahn. Track construction is entirely and track maintenance partly government financed both for long and short range trains.[citation needed] On the other hand, all rail vehicles are charged track access charges by DB Netz which in turn delivers (part of) its profits to the federal budget.

High speed rail started in the early 1990s with the introduction of the Inter City Express (ICE) into revenue service after first plans to modernize the rail system had been drawn up under the government of Willy Brandt. While the high speed network is not as dense as those of France or Spain, ICE or slightly slower (max. speed 200 km/h) Intercity (IC) serve most major cities. Several extensions or upgrades to high speed lines are under construction or planned for the near future, some of them after decades of planning.

The fastest high-speed train operated by Deutsche Bahn, the InterCityExpress or ICE connects major German and neighbouring international centres such as Zürich, Vienna, Copenhagen, Paris, Amsterdam and Brussels. The rail network throughout Germany is extensive and provides services in most areas. On regular lines, at least one train every two hours will call even in the smallest of villages during the day. Nearly all larger metropolitan areas are served by S-Bahn, U-Bahn, Straßenbahn and/or bus networks.

The German government on 13 February 2018 announced plans to make public transportation free as a means to reduce road traffic and decrease air pollution to EU-mandated levels.[16] The new policy will be put to the test by the end of the year in the cities of Bonn, Essen, Herrenberg, Reutlingen and Mannheim.[17] Issues remain concerning the costs of such a move as ticket sales for public transportation constitute a major source of income for cities.[18][needs update]

International freight trains

[edit]While Germany and most of contiguous Europe use 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge, differences in signalling, rules and regulations, electrification voltages, etc. create obstacles for freight operations across borders. These obstacles are slowly being overcome, with international (in- and outgoing) and transit (through) traffic being responsible for a large part of the recent uptake in rail freight volume. EU regulations have done much to harmonize standards, making cross border operations easier. Maschen Marshalling Yard near Hamburg is the second biggest in the world and the biggest in Europe. It serves as a freight hub distributing goods from Scandinavia to southern Europe and from Central Europe to the port of Hamburg and overseas. Being a densely populated prosperous country in the center of Europe, there are many important transit routes through Germany. The Mannheim–Karlsruhe–Basel railway has undergone upgrades and refurbishments since the 1980s and will likely undergo further upgrades for decades to come as it is the main route from the North Sea Ports to northern Italy via the Gotthard Base Tunnel.

S-Bahn

[edit]Almost all major metro areas of Germany have suburban rail systems called S-Bahnen (Schnellbahnen). These usually connect larger agglomerations to their suburbs and often other regional towns, although the Rhein-Ruhr S-Bahn connects several large cities. An S-Bahn calls at all intermediate stations and runs more frequently than other trains. In Berlin and Hamburg the S-Bahn has a U-Bahn-like service and uses a third rail whereas all other S-Bahn services rely on catenary power supply.

Rapid transit (U-Bahn)

[edit]

Relatively few cities have a full-fledged underground U-Bahn system; S-Bahn (suburban commuter railway) systems are far more common. In some cities the distinction between U-Bahn and S-Bahn systems is blurred; for instance, some S-Bahn systems run underground, have frequencies similar to U-Bahn, and form part of the same integrated transport network. A larger number of cities has upgraded their tramways to light rail standards. These systems are called Stadtbahn (not to be confused with S-Bahn).

Cities with U-Bahn systems are:

With the exception of Hamburg, all of those aforementioned cities also have a tram system, often with new lines built to light rail standards. Berlin and Hamburg (as well as the then independent city of Schöneberg whose lone subway line is today's line 4 of the Berlin U-Bahn) began building their networks before World War I whereas Nuremberg and Munich - despite earlier attempts in the 1930s and 1940s - only opened their networks in the 1970s (in time for the 1972 Summer Olympics in the case of Munich).

Cities with Stadtbahn systems can be found in the article Trams in Germany. Locals sometimes confuse Stadtbahn and "proper" U-Bahn as the logo for the former sometimes employs a white U on a blue background similar to the logo of the latter (in most cases, however, the Stadtbahn-logo includes additions to that U-logo). Furthermore, Stadtbahn systems often include partially or wholly underground sections (especially in city centers) and in the case of Frankfurt U-Bahn what is properly a Stadtbahn is even officially called an U-Bahn. To some extent this confusion was deliberate at the time of the opening of the Stadtbahn networks, as it was seen at the time to be more desirable to have a "proper" U-Bahn system than a "mere" tram system and many cities which embarked on Stadtbahn building projects did so with the official goal of eventually converting the entire network to U-Bahn standards.

Trams (Straßenbahn)

[edit]Germany was among the first countries to have electric streetcars, and Berlin has one of the longest tram networks in the world. Many West German cities abandoned their previous tram systems in the 1960s and 1970s while others upgraded them to "Stadtbahn" (~light rail) standard, often including underground sections. In the East, most cities retained or even expanded their tram systems and since reunification a trend towards new tram construction can be observed in most of the country. Today the only major German city without a tram or light rail system is Hamburg. Tram-train systems like the Karlsruhe model first came to prominence in Germany in the early 1990s and are implemented or discussed in several cities, providing coverage far into the rural areas surrounding cities. Trams exist in all but two of the states of Germany (Hamburg and Schleswig Holstein being the exception) and in 13 of the 16 state capitals (Wiesbaden being the capital outside the aforementioned states without a tram system). While there have been attempts to (re)-establish tram systems in many cities that formerly had them (for example Aachen, Kiel, Hamburg) as well as in some cities that never had them, but are comparatively close to a city that does (for example Erlangen, Wolfsburg), only a handful of such proposals have come to fruition since World War II - the Saarbahn (trams defunct in 1965; Saarbahn established in 1997) in Saarbrücken, Heilbronn Stadtbahn (defunct in 1955, re-established as an extension of Stadtbahn Karlsruhe in 1998) and a few extensions across the border - the Strasbourg tramway to Kehl and the Trams in Basel to Weil am Rhein.

Air transport

[edit]Short distances and the extensive network of motorways and railways make airplanes uncompetitive for travel within Germany. Only about 1% of all distance travelled was by plane in 2002.[9] But due to a decline in prices with the introduction of low-fares airlines, domestic air travel is becoming more attractive. In 2013 Germany had the fifth largest passenger air market in the world with 105,016,346 passengers.[19] However, the advent of new faster rail lines often leads to cuts in service by the airlines or even total abandonment of routes like Frankfurt-Cologne, Berlin-Hannover or Berlin-Hamburg.

Airlines

[edit]

Germany's largest airline is Lufthansa, which was privatised in the 1990s. Lufthansa also operates two regional subsidiaries under the Lufthansa Regional brand and a low-cost subsidiary, Eurowings, which operates independently. Lufthansa flies a dense network of domestic, European and intercontinental routes. Germany's second-largest airline was Air Berlin, which also operated a network of domestic and European destinations with a focus on leisure routes as well as some long-haul services. Air Berlin declared bankruptcy in 2017 with the last flight under its own name in October of that year.

Charter and leisure carriers include Condor, TUIfly, MHS Aviation and Sundair. Major German cargo operators are Lufthansa Cargo, European Air Transport Leipzig (which is a subsidiary of DHL) and AeroLogic (which is jointly owned by DHL and Lufthansa Cargo).

Airports

[edit]

Frankfurt Airport is Germany's largest airport, a major transportation hub in Europe and the world's twelfth busiest airport. It is one of the airports with the largest number of international destinations served worldwide. Depending on whether total passengers, flights or cargo traffic are used as a measure, it ranks first, second or third in Europe alongside London Heathrow Airport and Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport. Germany's second biggest international airport is Munich Airport, followed by Berlin Brandenburg Airport and Düsseldorf Airport.[20]

There are several more scheduled passenger airports throughout Germany, mainly serving European metropolitan and leisure destinations. Intercontinental long-haul routes are operated to and from the airports in Frankfurt, Munich, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Cologne/Bonn, Hamburg and Stuttgart.

Airports — with paved runways:

- total: 318

- over 3,047 m: 14

- 2,438 to 3,047 m: 49

- 1,524 to 2,437 m: 60

- 914 to 1,523 m: 70

- under 914 m: 125 (2013 est.)

Airports — with unpaved runways:

- total: 221

- over 3,047 m: 0

- 2,438 to 3,047 m: 0

- 1,524 to 2,437 m: 1

- 914 to 1,523 m: 35

- under 914 m: 185 (2013 est.)

Heliports: 23 (2013 est.)

Water transport

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

Waterways: 7,467 km (2013);[13] major rivers include the Rhine and Elbe; Kiel Canal is an important connection between the Baltic Sea and North Sea and one of the busiest waterways in the world,[21] the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal links Rotterdam on the North Sea with the Black Sea. It passes through the highest point reachable by ocean-going vessels from the sea.[22] The Canal has gained importance for leisure cruises in addition to cargo traffic. There are also regular boat trips on lakes, such as Lake Constance (Bodensee).[23]

Pipelines: oil 2,400 km (2013)[24]

Ports and harbours: Berlin, Bonn, Brake, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Cologne, Dortmund, Dresden, Duisburg, Emden, Fürth, Hamburg, Karlsruhe, Kiel, Lübeck, Magdeburg, Mannheim, Nuremberg, Oldenburg, Rostock, Stuttgart, Wilhelmshaven

The port of Hamburg is the largest sea-harbour in Germany and ranks #3 in Europe (after Rotterdam and Antwerpen), #17 worldwide (2016), in total container traffic.[25]

Merchant marine:

total: 427 ships

Ships by type: barge carrier 2, bulk carrier 6, cargo ship 51, chemical tanker 15, container ship 298, Liquified Gas Carrier 6, passenger ship 4, petroleum tanker 10, refrigerated cargo 3, roll-on/roll-off ship 6 (2010 est.)[13]

Ferries operate mostly between mainland Germany and its islands, serving both tourism and freight transport. Car ferries also operate across the Baltic Sea to the Nordic countries, Russia and the Baltic countries. Rail ferries operate across the Fehmahrnbelt, from Rostock to Sweden (both carrying passenger trains) and from the Mukran port in Sassnitz on the island of Rügen to numerous Baltic Sea destinations (freight only).

See also

[edit]![]() Driving in Germany travel guide from Wikivoyage

Driving in Germany travel guide from Wikivoyage

![]() Rail travel in Germany travel guide from Wikivoyage

Rail travel in Germany travel guide from Wikivoyage

- List of airports in Germany

- License plates in Germany

- List of motorways in Germany

- List of federal highways in Germany

- Tourism in Germany

- 9-Euro-Ticket

External links

[edit]- CIA World Factbook - see section on transportation

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.dw.com/en/regulations-eased-on-long-distance-busing/a-16354136

- ^ bundesregierung.de - The federal government says 40% of €164,000,000,000 spent on transport infrastructure where spent in the eastern part

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Road_freight_transport_by_journey_characteristics

- ^ https://www.fleeteurope.com/en/financial-models/europe/features/mobility-paradox-more-cars-less-mileage?a=FJA05&t[0]=Fleet%20Management&t[1]=Shared%20Mobility&curl=1

- ^ https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/irtad-road-safety-annual-report-2022.pdf

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Passenger_mobility_statistics

- ^ https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-01/erso-country-overview-2024-germany.pdf

- ^ Logistics, Oliver Wyman on Transportation &. "European Bus Upstarts Snatch 20% of Passengers from Rail". Forbes.

- ^ a b c "Transport in Germany". International Transport Statistics Database. iRAP. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ "BMVBS - Verkehr und Mobilität-Straße". BMVBS. Archived from the original on 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ^ "Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder". Archived from the original on 2003-11-15.

- ^ "Traffic and Accident Data: Summary Statistics - Germany" (PDF). Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen (Federal Highway Research Institute). Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen. September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ^ a b c "CIA World Facebook: Germany".

- ^ "German Railway Financing" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-10.

- ^ "Market Analysis: German Railways 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (2018-02-14). "German cities to trial free public transport to cut pollution". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- ^ "POLITICO Morgen Europa: Freie Öffis gegen schlechte Luft — Neues zum Spitzenkandidatenprozess — In eigener Sache". POLITICO. 2018-02-13. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- ^ "Kostenloser Nahverkehr: Allein in Hamburg so teuer wie eine Elbphilharmonie pro Jahr". Spiegel Online. 2018-02-14. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- ^ World Bank Datebase, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.AIR.PSGR

- ^ "Airports with the most passengers in Germany 2022". Statista. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ Stewart, Alison (2020-01-23). "Germany's Kiel Canal: The world's busiest man-made waterway is an engineer feat". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "Water locks on the rivers of Europe". Darby's Destinations. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "Welcome to the most beautiful river journey in Europe". Schweizerische Schifffahrtsgesellschaft Untersee und Rhein (URh). Retrieved 2025-02-08.

- ^ Germany. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Top 50 World Container Ports". World Shipping Council. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

KSF

KSF