-

Looking north towards the Marin Headlands from the western shore.

-

Looking south towards Yerba Buena Island and the Bay Bridge from the western shore.

-

Treasure Island Marina on the island's south shore

-

The bridge's new eastern span is best viewed from near the marina

-

The San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, Yerba Buena Island, Treasure Island, and San Francisco, in an afternoon aerial view looking into the sun

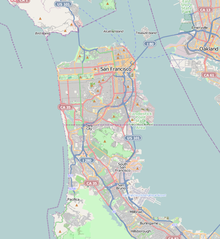

Treasure Island, San Francisco

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 20 min

Treasure Island

Magic Isle[1] | |

|---|---|

Landform and neighborhood | |

![Treasure Island is "5,520 feet long by 3,410 feet wide"[1] and has the Treasure Island Marina on the south near Yerba Buena Island (bottom)](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Wfm_yerba_buena_treasure_islands_usgs.jpg/200px-Wfm_yerba_buena_treasure_islands_usgs.jpg) Treasure Island is "5,520 feet long by 3,410 feet wide"[1] and has the Treasure Island Marina on the south near Yerba Buena Island (bottom) | |

Treasure Island is the northernmost area of San Francisco's District 6 | |

| Coordinates: 37°49′30″N 122°22′16″W / 37.825°N 122.371°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Constructed | 1936–37 |

| Named for | Treasure Island (novel) |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Matt Dorsey (Dist. 6) |

| • Assemblymember | Matt Haney (D)[2] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[2] |

| • U. S. rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[3] |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.9 sq mi (2 km2) |

| • Land | 0.9 sq mi (2 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) 0% |

| Population (2024 estimate)[4] | |

• Total | 2,800 |

| • Density | 3,100/sq mi (1,200/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 94130 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

| GNIS feature IDs[5] | 236528 (island) 2624152 (Building 157) 2506912 (Job Corps Ctr) |

| Wikimedia Commons | Treasure Island, California |

| Website | Treasure Island Development Authority |

| Reference no. | 987[6] |

Treasure Island is an artificial island in San Francisco Bay, and a neighborhood in the City and County of San Francisco. Built in 1936–37 for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, the island was named by Clyde Milner Vandeburg, part of the Fair's public relations team.[7]: 8 Its World's Fair site is a California Historical Landmark.[6] Buildings there have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the historical Naval Station Treasure Island, an auxiliary air facility (for airships, blimps, dirigibles, planes and seaplanes), are designated in the Geographic Names Information System.[5] Treasure Island is connected to Yerba Buena Island, another (natural) auxiliary island of San Francisco, by a causeway, creating access to Interstate 80.

Geography

[edit]The San Francisco census tract that includes Treasure Island extends up and down San Francisco Bay and includes a small uninhabited tip of western Alameda Island.[8] Yerba Buena and Treasure Island together have a land area[verification needed] of 576.7 acres (233.4 ha) with – in 2010 – a total population of 2,500.[9] Treasure Island alone is 393 acres. It is connected by a 900 ft (270 m) causeway to Yerba Buena Island, which in turn has on- and off-ramps to Interstate 80 on the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

The island has a marina and a bikeway connecting to the newly completed Eastern span replacement of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. Raised walkways circumscribe nearly the entire island along five streets (Avenue of the Palms, Perimeter Road, Avenue N, Pan American World Airways Esplanade and Clipper Cove Way, formerly known as 1st Street).[citation needed]

History

[edit]Prior to the island's construction by the United States government, "Yerba Buena Shoals" of rock[1] north of the transbay island had less than 27 ft (8.2 m) clearance and were a shipping hazard.[10] The 400-acre (1.6 km2) island was constructed by emplacing 287,000 short tons (260,000 t) of quarried rock in the shoals for the island/causeway perimeter rock walls (a freshwater reservoir was quarried in the rock of Yerba Buena Island).[10] Approximately 23 feet (7.0 m) of dredged bay sand filled the interior, was mitigated from salt, and then 50,000 cubic yards (38,000 m3) topsoil[10] was used for planting 4,000 trees, 70,000 shrubs, and 700,000 flowering plants.[1] Facility construction had begun by March 4, 1937, when two hangars were being built.

| External media | |

|---|---|

| Images | |

| Video | |

On February 18, 1939, the 'Magic City'[11] opened with a "walled city" of several fair ground courts: a central Court of Honor, a Court of the East, a Port of Trade Winds on the south and on the north: a Court of Pacifica, a 12,000-car parking lot, and the adjacent National Building, the $1.5M Federal Building, the Hall of Western States, the $800K administration building, various exhibit halls for industries (e.g., "Machinery, Science, and Vacationland"), and two 335-by-78-foot (102 m × 24 m) hangars planned for post-exposition use by Pan Am flying boats (e.g., the China Clipper through 1944[6]) using the Port of Trade Winds Harbor later referred to as Clipper Cove between the two islands. In addition to Building 2 (Hangar 2) and Building 3 (Hangar 3), remaining exposition buildings include Building 1 (Streamline Moderne architecture) intended after the expo as the Pan American World Airways terminal. The expo's Magic Carpet Great Lawn also remains.)[12]

A couplet from the song "Lydia the Tattooed Lady", in the Marx Brothers' 1939 film, At The Circus, reads "Here is Grover Whalen unveilin' the Trylon/Over on the West Coast we have Treasure Island", citing, in the Trylon and Treasure Island, two prominent features of international civic events happening that year (as the 1939 New York World's Fair vied for tourist patrons with the Golden Gate International Expo).

Treasure Island and the exposition are featured in one of James A. Fitzpatrick's Technicolor travel features, “Night Descends on Treasure Island,” released in 1940.[13]

Military base

[edit]

Treasure Island was originally intended to become a second airport for San Francisco, augmenting the existing San Francisco Municipal Airport, now SFO. But with war looming, the Navy moved in.

Naval Station (NAVSTA) Treasure Island began under a 1941[14] war lease as a United States Navy "reception center".[15] On April 17, 1942, the U.S. Navy cut short an ownership dispute with the city by seizing the island.[14] The Navy eventually compensated the city with $10 million in improvements to the existing airport, including reclaiming 93 acres of land, and postwar ownership of all military improvements.[16] (A widely cited Navy report[17] gave rise to the urban legend that the Navy swapped the island for land on which the city then built SFO. In fact, the airport had been operating in its current location since 1927.)

NAVSTA Treasure Island had a Naval Auxiliary Air Facility[5] in order to support helicopters, fixed wing planes, seaplanes, blimps, dirigibles and airships and a U.S.Navy/USMC electronics school. During World War II over 12,000 men a day were processed here for Pacific area assignments, and thousands more were processed for separation in the aftermath of the war.[18] The psychiatric ward of the naval base at Treasure Island was used to study and experiment on naval sailors who were being discharged for being homosexual.[19]

Since before the 1950s, and through the 1990s (throughout both Korean & Vietnam wars) the U.S. Navy's Naval Technical Training Center (NTTC) – Treasure Island, was operational. Multiple Maintenance Skills were part of the curriculum there, including training of Electronic Technicians (ET) in Radiation and Detection equipment (RADIAC), Communications & Radar systems, as well as training of Shipfitter and Damage Control Technicians, which also covered Nuclear Biological & Chemical (NBC) Warfare Decontamination (DECON) techniques. In 1972 a new U.S. Navy Rate consisting of the old Shipfitter and Damage Control Technician ratings was created. This New U.S. Navy Rate was Hull Maintenance Technician (HT). The Navy later realized that Damage Control is such a large responsibility, it needed a rating specifically tasked with those duties, hence the reemergence of the Damage Controlman Rating in 1988.[20]

In recognition of his naval base leadership and development efforts since the inception of US Naval Station Treasure Island, Rear Admiral Hugo Wilson Osterhaus Square was established in front of Building 1 Administration Building, Treasure Island. Medal of Honor and Navy Cross recipient USMC Gunnery Sgt John Basilone movie theatre Building 401 @ 680 Avenue I was established in recognition as being one of the earliest World War II heroes.

The station was identified by the 1991 Base Realignment and Closure Commission, and NAVSTA Treasure Island closed in 1997. Remaining military structures included Bldg. 600 @ 750 Avenue M (former Naval Firefighting School, now SFFD's Treasure Island Training Facility & Temporary SFFD Fire Station 48), Bldg. 157 (Navy Fire station 2 built circa 1942 wood-frame building which lacks modern earthquake Seismic retrofit) @ 849 Avenue D (SFFD Station 48 closed March 7, 2014, due to health hazards & excessive deferred maintenance), and the 20,000 sq ft (1,900 m2) Bldg. 180 by US Naval Station Way & California Ave (now a winery).[21]

SAC radar station

[edit]The Treasure Island Radar Bomb Scoring Site (call sign San Francisco Bomb Plot)[22][unreliable source] was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) automatic tracking radar facility established on the island.[specify] Major Posey was the c. 1948 commander[citation needed] of Detachment B (Capt Carlson on August 1, 1949)[23] which evaluated simulated bombing missions on targets in the San Francisco metropolitan area for maintaining Cold War bomber crews' proficiency. A nearby "Stockton Bomb Plot (Det I)" moved to Charlotte in 1950, and the Treasure Island unit was redesignated Detachment 13 in 1951, the year 3 other SAC detachments used a nearby staging/preparation area for deploying via the bay for Korean War ground-directed bombing (cf. the Sacramento Bomb Plot at a McClellan AFB Annex in 1951.)[citation needed] On October 16, 1951, Treasure Island's Det 13 was assigned under March AFB's 3933rd Radar Bomb Scoring Squadron before moving from the island by August 10, 1954, when the 11th RBS Squadron was activated.

Film stages and settings

[edit]From the late 1980s, Treasure Island's old aircraft Hangar 2 (Building 2) and Hangar 3 (Building 3) served as sound stages for film-making and TV, e.g., The Matrix ("bullet time" visual effect), Rent, and The Pursuit of Happyness.[citation needed] Treasure Island was a film setting of the 1939 Charlie Chan at Treasure Island, 1989 Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (Berlin airport scene), 1995 Copycat (private compound), 1997 Flubber, 1998 What Dreams May Come, 1998 Patch Adams, 1998 The Parent Trap and 1999 Bicentennial Man. An establishing shot of the 1954 The Caine Mutiny shows the main gate and Administration Bldg 1 to indicate the location of the fictitious court martial. For three years Treasure Island served as the site of the Battlebots TV show. The offices and penthouse apartment sets in Nash Bridges were located on the island during the show's production (1996–2001).[26] The island was featured as the base of operations for the prototypers in the 2008 Discovery Channel series Prototype This!. Building 180 (warehouse) and Building 111 (former firehouse) on Treasure Island served as film settings for an NBC series titled Trauma. In 2018, Treasure Island Museum building served as a mental hospital setting for the Netflix series titled The OA. MythBusters also regularly shot footage of their various experiments on the island.[27][28]

Remediation and redevelopment

[edit]Cleanup crews spent several weeks cleaning the island's coast from the 2007 Cosco Busan oil spill just a few hundred yards from Treasure Island, and in 2009 the Navy agreed to sell the island to the city for $105 million[29] as part of a redevelopment project. The federal government still maintains an active presence on 40 acres (16 ha) occupied by the United States Department of Labor Job Corps (not part of the redevelopment). The Job Corps moved in and took over 40 acres (16 ha) and 13 building facilities just after the US Navy vacated the island. The Administration Building (Bldg. 1) and Hall of Transportation (Bldg. 2) were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2008. On June 8, 2011, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved new neighborhood development for 19,000 people over the next 20–30 years by Wilson Meany Sullivan, Lennar Urban, and Kenwood Investments.[30] The 2012–2014 US$1.5 billion Treasure Island Development project for up to 8,000 new residences, 140,000 sq ft (13,000 m2) of new commercial and retail space, 100,000 sq ft (9,300 m2) of new office space, 3 hotels, new Fire station and 300 acres (120 ha) of parks.[31] The island's gas station pumps and canopy were also removed (the island has a high risk of soil liquefaction and tsunami damage in an earthquake). All island natural gas, electricity, sewer and water utilities are serviced by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. The island experiences several power outages per year.[32] Ground broke on the island's ferry terminal in 2019.[33]

By December 2010, Navy contractors had removed 16,000 cubic yards (12,000 m3) of contaminated dirt from the site, "some with radiation levels 400 times the Environmental Protection Agency’s human exposure limits for topsoil."[34] The contaminated dirt is to be replaced by dirt removed during construction of the fourth Caldecott Tunnel bore.[35] In April 2013, caesium-137 levels three times higher than previously[when?] recorded were found (the island hosted "radioactive ships from Bikini Atoll atomic tests and [was] a major education center training personnel for nuclear war"[36]—the USS Pandemonium (PCDC-1)[37] mockup had begun nuclear training in 1957.[38][39]

Education

[edit]The island is a part of the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD). Zoned elementary schools serving sections of the island include John Yehall Chin (North Beach) and Sherman (Marina).[40]

SFUSD previously operated Treasure Island K-8 School. In Spring 2004, the SFUSD board voted to close the middle school portion but keep the elementary school in operation. In its final semester of operation, it had 95 students. In December 2004, the district voted to close altogether effective the beginning of 2005. Initially, the Treasure Island Homeless Development Initiative fought to save the school, but after discipline and staffing issues occurred in 2004, the group stopped its efforts. Heather Knight of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that year "Even people who had fought to save the school earlier this year now admit it's no longer worth saving."[41]

Gallery

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d McGloin, John Bernard. "Symphonies in Steel: Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate". The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco (SFmuseum.net). Retrieved October 22, 2013.

The Secretary of War approved the request that its execution be undertaken by the Army Corps of Engineers. While a group of such specialists applied their talents to the reclamation of the 'Yerba Buena Shoals', the day-by-day details were efficiently cared for by Colonel Fred Butler, U.S.A., who had years of army engineering experience behind him at this time. The fill to form Treasure Island was obtained by dredging operations; the island covered an area of 400 acres [160 ha], 5,520 feet [1,680 m] long by 3,410 feet [1,040 m] wide.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b "94130 Zip Code (San Francisco, California) Profile: homes, apartments, schools, population, income, averages, housing, demographics, location, statistics, sex offenders, residents and real estate info". City-data.com. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ a b c * "Treasure Island (236528)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 25, 2013. "374929N 1222216W...374937N 1222241W"

- "San Francisco Fire Department Station 48 Treasure Island (2624152)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 25, 2013. "Building 157...374931N 1222226W"

- "Treasure Island Job Corps Center (2506912)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

655 Avenue H

- "Naval Station Treasure Island (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- "Treasure Island Naval Auxiliary Air Facility (historical) (1988803)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ a b c Office of Historic Preservation. "San Francisco". California Historical Landmarks. California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ Cotter, Bill (2021). San Francisco's 1939-1940 World's Fair: The Golden Gate International Exposition. Charleston, South Carolina: Images of America, Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467106160.

- ^ "San Francisco Census Tract Outline Map" (PDF) (Map). Census 2000. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ United States Census, 2010[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Workers of the Federal Writers’ Project (1938). "Trail Ends for '39ers". Almanac for Thirty-Niners. San Francisco Works Progress Administration – via SFmuseum.net.

- ^ James, Jack; Weller, Earle Vonard (1941). Treasure island, "The Magic City," 1939-1940; The Story of the Golden Gate International Exposition. Pisani printing and publishing company. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "San Francisco Attractions". SF-Attractions.

- ^ "Night Descends on Treasure Island". prod.tcm.com. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ a b "Treasure Isle Goes to Navy: City Upset Over Offer, May Dispute Price". The San Francisco News. April 17, 1942. Retrieved October 26, 2013 – via SFmuseum.net.

- ^ "Treasure Island Accord". The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco.

- ^ Flynn, William (1954). Men, Money and Mud – The Story of San Francisco International Airport. W. Flynn Publications. p. 37.

- ^ Hice, Eric; Schierling, Daniel (1996). Historical Study of Yerba Buena Island, Treasure Island, and their Buildings. pp. 2–17.

- ^ Lemon, Sue. "Treasure Island, Naval Station, 1937 - ." United States Navy and Marine Corps Bases, Domestic. Paolo E. Coletta, Editor. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1985.

- ^ Stryker, Susan (1996). Gay By the Bay: A history of Queer Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. p. 30. ISBN 0-8118-1187-5.

- ^ "DEV Charlie Marine Air Support Radar Team". The Korean War Project.

- ^ "The Winery SF". Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ Tim in San Mateo (October 2, 2002). "San Francisco Bomb Plot". Yahoo! Groups. Self-published via Yahoo!. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ Martin, Jack S. (September 23, 1949). Report of Investigation: Project Grudge (Special Inquiry). Fairfield-Suisun Air Force Base: USAF Office of Special Investigations. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

On 14 September 1949, Captain Howard A. Carlson,12456-A/ Detachment Commander, Detachment B, 3903 Radar Bomb Scoring Squadron, Treasure Island, San Francisco, California, was interviewed and stated that on 1 August 1949, two radar testing devices were released; one at approximately 1000 hours, PST, and another at 1400 hours, PST.

- ^ a b "Home". Treasure Island Museum Association. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Museum and Its Collection". Treasure Island Museum Association. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ SF filming locations for Nash Bridges

- ^ "'Mythbusters' Tackles Titanic Debate". CBS News. October 9, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ Marek, Grant (September 28, 2019). "How Treasure Island found its way into the most iconic Indiana Jones film". SFGate. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ John Cote, "City to get Treasure Island for $105 million." SF Gate, December 17, 2009

- ^ Kane, Will (June 8, 2011). "S.F. approves Treasure Island plan". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ "Treasure Island: Development Project". Treasure Island Development Authority. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Power Outages On Treasure Island In San Francisco". Power Outages On Treasure Island In San Francisco.

- ^ Fagone and Dizikes (September 10, 2019). "Treasure Island ferry terminal breaks ground in anticipation of 8,000 new SF homes". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Matt Smith (August 17, 2012). "Radiation Contamination on Treasure Island More Widespread Than Reported". The Bay Citizen.

- ^ Cuff, Denis (November 13, 2013). "Caldecott Tunnel forth bore to ease traffic backups during reverse commute". Mercury News. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Matt; Mierskowski, Katherine (April 12, 2013). "Soil tests find cesium, linked to cancer risk, up to 3 times higher than previously acknowledged". The Bay Citizen. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

Until the early 1990s, the Navy operated atomic warfare training academies on Treasure Island, using instruction materials and devices that included radioactive plutonium, cesium, tritium, cadmium, strontium, krypton and cobalt. These supplies were stored at various locations around the former base, including supply depots, classrooms and vaults, and in and around a mocked-up atomic warfare training ship—the USS Pandemonium.

- ^ The Sandusky Register on. Newspapers.com (1957-03-21). Retrieved on 2014-05-10.

- ^ Ron Russell (May 24, 2006). "Toxic Acres: The fill below Treasure Island is filled with dangerous toxins left by the Navy". SF Weekly. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Ashley Bates, "Radioactive Isle." East Bay Express, September 9, 2012

- ^ "Final Recommendations for Elementary Attendance Areas Prepared for September 28, 2010 Board Meeting." San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved on April 18, 2018.

- ^ Knight, Heather (December 6, 2005). "SAN FRANCISCO / Board votes to close Treasure Island school". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Katie Canales (December 16, 2019). "San Francisco's housing market is so dire that the city's radioactive Treasure Island is finally getting a $6 billion makeover. Meet the residents who have lived on it for years". Business Insider.

External links

[edit] Media related to Treasure Island, San Francisco at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Treasure Island, San Francisco at Wikimedia Commons- Treasure Island Music Festival

- Treasure Island School at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

KSF

KSF