Triangular bipyramid

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 9 min

| Triangular bipyramid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Bipyramid Johnson J11 – J12 – J13 |

| Faces | 6 triangles |

| Edges | 9 |

| Vertices | 5 |

| Vertex configuration | [1] |

| Symmetry group | |

| Dual polyhedron | triangular prism |

| Properties | convex |

| Net | |

| |

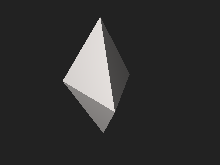

In geometry, the triangular bipyramid[a] is the hexahedron with six triangular faces, constructed by attaching two tetrahedrons face-to-face. All of its faces are equilateral, and it is an example of a deltahedron and of a Johnson solid. The triangular bipyramid has a graph with its construction involving the wheel graph.

Many polyhedrons related to the triangular bipyramid, such as new kinds of similar shapes in various constructions, and its dual the triangular prism. The many applications of triangular bipyramid include the trigonal bipyramid molecular geometry that describes its atom cluster, the solution of Thomson problem, and the representation of colors by the eighteenth century.

Construction[edit]

The triangular bipyramid is constructed like most other bipyramids, by attaching two tetrahedrons face-to-face.[3] This construction involves the removal of their base and attaching them, resulting in six triangles, five vertices, and nine edges.[4] A polyhedra with all faces are equilateral triangles is known as deltahedron. There are eight different convex deltahedra, one of which is the triangular bipyramid.[2] More generally, the Johnson solids are the convex polyhedron in which all of the faces are regular, and every convex deltahedra is a Johnson solid. The triangular bipyramid is one of them, enumerated as , the twelfth Johnson solid.[5]

Properties[edit]

The triangular bipyramid with edge length has surface area:

The triangular bipyramid has three-dimensional point group symmetry, the dihedral group of order six: the appearance of the triangular bipyramid is unchanged as it rotated by one-, two-thirds, and full angle around the axis of symmetry (a line passing through two vertices and base's center vertically), and it has mirror symmetry relative to any bisector of the base; reflecting across a horizontal plane gives the same result. The dihedral angles of a triangular bipyramid can be calculated by adding the angle of two regular tetrahedra: the angle of tetrahedron between adjacent triangular faces itself is , and the dihedral angle of adjacent triangles, on the edge that is attached by two regular tetrahedra is approximately twice of that:[1]

Graph[edit]

According to Steinitz's theorem, a graph can be represented as the skeleton of a polyhedron if it is planar and 3-connected graph. In other words, the edges of that graph do not cross but only intersect at the point, and one of any two vertices leaves a connected subgraph when removed. The triangular bipyramid is represented by a graph with nine edges, constructed by adding one vertex connected other three vertices of wheel graph , where represents the graph of pyramid with -sided polygonal base.[7][8]

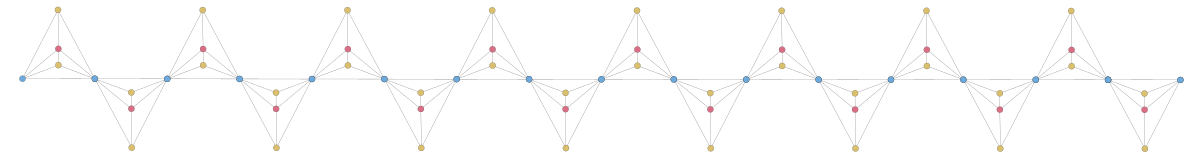

Sajjad, Sardar & Pan (2024) constructed a chain of triangular bipyramid graphs by arranging them linearly, as in the illustration below. The resistance distance (measurement of two vertices of a graph using the electrical network) of such construction can be computed by applying the series and parallel principles, star-mesh transformation, and Y-Δ transformation. Its structure is an example of the metal-organic frameworks study.[9]

Related polyhedra[edit]

Some types of triangular bipyramids may be derived based on various constructions. For example, the Kleetope of polyhedra is a construction involving the attachment of pyramids; in the case of the triangular bipyramid, its Kleetope is constructed by gluing tetrahedrons onto its faces, and its skeleton represents the Goldner–Harary graph by Steinitz's theorem.[10][11] Another type is by cutting off all the vertices of a triangular bipyramid; this process is known as truncation.[12]

The bipyramids are dual of prisms, for which the bipyramids vertices correspond to the faces of the prism, and the edges between pairs of vertices of one correspond to the edges between pairs of faces of the other. Consequently, the dualization of a dual polyhedron is the original polyhedron itself. Hence, the triangular bipyramid is the dual polyhedron of the triangular prism, and the triangular prism is the dual polyhedron of the triangular bipyramid.[13][4] The triangular prism has five faces, nine edges, and six vertices, and its symmetry is shared with its dual.[4]

Applications[edit]

The Thomson problem concerns the minimum-energy configuration of charged particles on a sphere. One of them is a triangular bipyramid, which is a known solution for the case of five electrons.[14] This solution is aided by the mathematically rigorous computer.[15]

In the geometry of chemical compound, the trigonal bipyramidal molecular geometry may be described as the atom cluster of the triangular bipyramid. This molecule has a main-group element without an active lone pair, as described by a model that predicts the geometry of molecules known as VSEPR theory.[16] Some examples of this structure are the phosphorus pentafluoride and phosphorus pentachloride in the gas phase.[17]

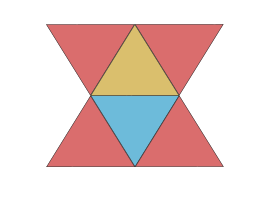

In the study of color theory, the triangular bipyramid was used to represent the three-dimensional color order system in primary color. The German astronomer Tobias Mayer presented in 1758 that each of its vertices represents the colors: white and black are, respectively, the top and bottom vertices, whereas the rest of the vertices are red, blue, and yellow.[18][19]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Johnson, Norman W. (1966). "Convex polyhedra with regular faces". Canadian Journal of Mathematics. 18: 169–200. doi:10.4153/cjm-1966-021-8. MR 0185507. S2CID 122006114. Zbl 0132.14603.

- ^ a b Trigg, Charles W. (1978). "An infinite class of deltahedra". Mathematics Magazine. 51 (1): 55–57. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1978.11976675. JSTOR 2689647. MR 1572246.

- ^ a b Rajwade, A. R. (2001). Convex Polyhedra with Regularity Conditions and Hilbert's Third Problem. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. Hindustan Book Agency. p. 84. doi:10.1007/978-93-86279-06-4. ISBN 978-93-86279-06-4.

- ^ a b c d King, Robert B. (1994). "Polyhedral Dynamics". In Bonchev, Danail D.; Mekenyan, O.G. (eds.). Graph Theoretical Approaches to Chemical Reactivity. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1202-4. ISBN 978-94-011-1202-4.

- ^ Uehara, Ryuhei (2020). Introduction to Computational Origami: The World of New Computational Geometry. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-4470-5. ISBN 978-981-15-4470-5.

- ^ Berman, Martin (1971). "Regular-faced convex polyhedra". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 291 (5): 329–352. doi:10.1016/0016-0032(71)90071-8. MR 0290245.

- ^ Tutte, W. T. (2001). Graph Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 113.

- ^ Pisanski, Tomaž; Servatius, Brigitte (2013). Configuration from a Graphical Viewpoint. Springer. p. 21. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-8364-1. ISBN 978-0-8176-8363-4.

- ^ Sajjad, Wassid; Sardar, Muhammad S.; Pan, Xiang-Feng (2024). "Computation of resistance distance and Kirchhoff index of chain of triangular bipyramid hexahedron". Applied Mathematics and Computation. 461: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2023.128313.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (1967). Convex Polytopes. Wiley Interscience. p. 357.. Same page, 2nd ed., Graduate Texts in Mathematics 221, Springer-Verlag, 2003, ISBN 978-0-387-40409-7.

- ^ Ewald, Günter (1973). "Hamiltonian circuits in simplicial complexes". Geometriae Dedicata. 2 (1): 115–125. doi:10.1007/BF00149287. S2CID 122755203.

- ^ Haji-Akbari, Amir; Chen, Elizabeth R.; Engel, Michael; Glotzer, Sharon C. (2013). "Packing and self-assembly of truncated triangular bipyramids". Phys. Rev. E. 88 (1): 012127. arXiv:1304.3147. Bibcode:2013PhRvE..88a2127H. doi:10.1103/physreve.88.012127. PMID 23944434. S2CID 8184675..

- ^ Sibley, Thomas Q. (2015). Thinking Geometrically: A Survey of Geometries. Mathematical Association of American. p. 53.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A.; Hardin, R. H.; Duff, T. D. S.; Conway, J. H. (1995), "Minimal-energy clusters of hard spheres", Discrete & Computational Geometry, 14 (3): 237–259, doi:10.1007/BF02570704, MR 1344734, S2CID 26955765

- ^ Schwartz, Richard Evan (2013). "The Five-Electron Case of Thomson's Problem". Experimental Mathematics. 22 (2): 157–186. doi:10.1080/10586458.2013.766570.

- ^ Petrucci, R. H.; W. S., Harwood; F. G., Herring (2002). General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 413–414. ISBN 978-0-13-014329-7. See table 11.1.

- ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-13-039913-7.

- ^ Kuehni, Rolf G. (2003). Color Space and Its Divisions: Color Order from Antiquity to the Present. John & Sons Wiley. p. 53.

- ^ Kuehni, Rolf G. (2013). Color: An Introduction to Practice and Principles. John & Sons Wiley. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-118-17384-8.

External links[edit]

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Triangular dipyramid" ("Johnson solid") at MathWorld.

- Conway Notation for Polyhedra Try: dP3

KSF

KSF