United States courts of appeals

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

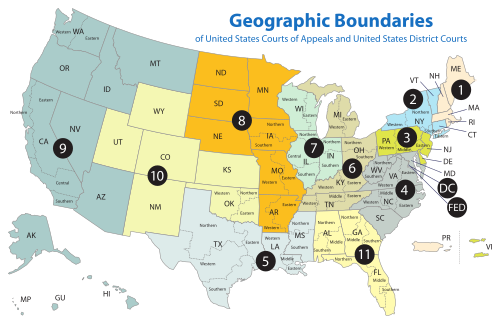

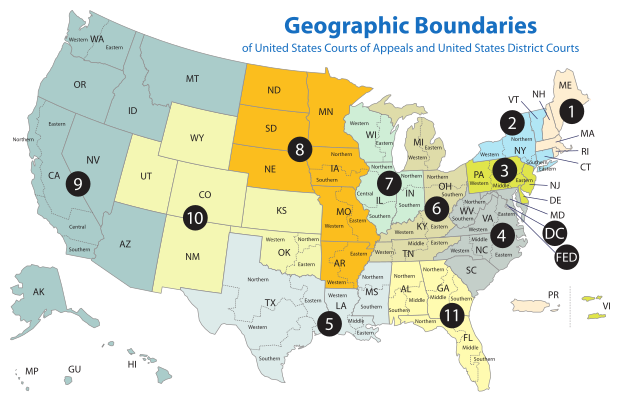

The United States courts of appeals, or Federal Circuit Courts or U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. They hear appeals of cases from the United States district courts and some U.S. administrative agencies, and their decisions can be appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. The courts of appeals are divided into 13 "Circuits".[1][2][3][4] Eleven of the circuits are numbered "First" through "Eleventh" and cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals from the U.S. district courts within their borders. The District of Columbia Circuit covers only Washington, DC. The Federal Circuit hears appeals from federal courts across the entire United States in cases involving certain specialized areas of law.

The United States courts of appeals are considered the most powerful and influential courts in the United States after the Supreme Court. Because of their ability to set legal precedent in regions that cover millions of Americans, the United States courts of appeals have strong policy influence on U.S. law. Moreover, because the Supreme Court chooses to review fewer than 3% of the 7,000 to 8,000 cases filed with it annually,[5] the U.S. courts of appeals serve as the final arbiter on most federal cases.

There are 179 judgeships on the U.S. courts of appeals authorized by Congress in 28 U.S.C. § 43 pursuant to Article III of the U.S. Constitution. Like other federal judges, they are nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the United States Senate. They have lifetime tenure, earning (as of 2023) an annual salary of $246,600.[6] The actual number of judges in service varies, both because of vacancies and because senior judges who continue to hear cases are not counted against the number of authorized judgeships.

Decisions of the U.S. courts of appeals have been published by the private company West Publishing in the Federal Reporter series since the courts were established. Only decisions that the courts designate for publication are included. The "unpublished" opinions (of all but the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits) are published separately in West's Federal Appendix, and they are also available in on-line databases like LexisNexis or Westlaw. More recently, court decisions have also been made available electronically on official court websites. However, there are also a few federal court decisions that are classified for national security reasons.

The circuit with the fewest appellate judges is the First Circuit, and the one with the most appellate judges is the geographically large and populous Ninth Circuit in the West. The number of judges that the U.S. Congress has authorized for each circuit is set forth by law in 28 U.S.C. § 44, while the places where those judges must regularly sit to hear appeals are prescribed in 28 U.S.C. § 48.

Although the courts of appeals are frequently called "circuit courts", they should not be confused with the former United States circuit courts, which were active from 1789 through 1911, during the time when long-distance transportation was much less available, and which were primarily first-level federal trial courts that moved periodically from place to place in "circuits" in order to serve the dispersed population in towns and the smaller cities that existed then. The "courts of appeals" system was established in the Judiciary Act of 1891.[7]

Procedure

[edit]Because the courts of appeals possess only appellate jurisdiction, they do not hold trials. Only courts with original jurisdiction hold trials and thus determine punishments (in criminal cases) and remedies (in civil cases). Instead, appeals courts review decisions of trial courts for errors of law.[citation needed] Accordingly, an appeals court considers only the record (that is, the papers the parties filed and the transcripts and any exhibits from any trial) from the trial court, and the legal arguments of the parties.[citation needed] These arguments, which are presented in written form and can range in length from dozens to hundreds of pages, are known as briefs. Sometimes lawyers are permitted to add to their written briefs with oral arguments before the appeals judges. At such hearings, only the parties' lawyers speak to the court.

The rules that govern the procedure in the courts of appeals are the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. In a court of appeals, an appeal is almost always heard by a "panel" of three judges who are randomly selected from the available judges (including senior judges and judges temporarily assigned to the circuit). Some cases, however, receive an en banc hearing. Except in the Ninth Circuit Court, the en banc court consists of all of the circuit judges who are on active status, but it does not include the senior or assigned judges (except that under some circumstances, a senior judge may participate in an en banc hearing who participated at an earlier stage of the same case).[8] Because of the large number of Appellate Judges in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (29), only ten judges, chosen at random, and the Chief Judge hear en banc cases.[9]

Many decades ago, certain classes of federal court cases held the right of an automatic appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. That is, one of the parties in the case could appeal a decision of a court of appeals to the Supreme Court, and it had to accept the case. The right of automatic appeal for most types of decisions of a court of appeals was ended by an Act of Congress, the Judiciary Act of 1925, which also reorganized many other things in the federal court system. Passage of this law was urged by Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

The current procedure is that a party in a case may apply to the Supreme Court to review a ruling of the circuit court. This is called petitioning for a writ of certiorari, and the Supreme Court may choose, in its sole discretion, to review any lower court ruling. In extremely rare cases, the Supreme Court may grant the writ of certiorari before the judgment is rendered by the court of appeals, thereby reviewing the lower court's ruling directly. Certiorari before judgment was granted in the Watergate scandal-related case, United States v. Nixon,[10] and in the 2005 decision involving the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, United States v. Booker.[11]

A court of appeals may also pose questions to the Supreme Court for a ruling in the midst of reviewing a case. This procedure was formerly used somewhat commonly, but now it is quite rare. For example, while between 1937 and 1946 twenty 'certificate' cases were accepted, since 1947 the Supreme Court has accepted only four.[12] The Second Circuit, sitting en banc, attempted to use this procedure in the case United States v. Penaranda, 375 F.3d 238 (2d Cir. 2004),[13] as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Blakely v. Washington,[14] but the Supreme Court dismissed the question.[15] The last instance of the Supreme Court accepting a set of questions and answering them was in 1982's City of Mesquite v. Aladdin's Castle, Inc.[16]

A court of appeals may convene a Bankruptcy Appellate Panel to hear appeals in bankruptcy cases directly from the bankruptcy court of its circuit. As of 2008[update], only the First, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits have established a Bankruptcy Appellate Panel. Those circuits that do not have a Bankruptcy Appellate Panel have their bankruptcy appeals heard by the district court.[17]

Courts of appeals decisions, unlike those of the lower federal courts, establish binding precedents. Other federal courts in that circuit must, from that point forward, follow the appeals court's guidance in similar cases, regardless of whether the trial judge thinks that the case should be decided differently.

Federal and state laws can and do change from time to time, depending on the actions of Congress and the state legislatures. Therefore, the law that exists at the time of the appeal might be different from the law that existed at the time of the events that are in controversy under civil or criminal law in the case at hand. A court of appeals applies the law as it exists at the time of the appeal; otherwise, it would be handing down decisions that would be instantly obsolete, and this would be a waste of time and resources, since such decisions could not be cited as precedent. "[A] court is to apply the law in effect at the time it renders its decision, unless doing so would result in manifest injustice, or there is statutory direction or some legislative history to the contrary."[18]

However, the above rule cannot apply in criminal cases if the effect of applying the newer law would be to create an ex post facto law to the detriment of the defendant.

Decisions made by the circuit courts only apply to the states within the court's oversight, though other courts may use the guidance issued by the circuit court in their own judgments. While a single case can only be heard by one circuit court, a core legal principle may be tried through multiple cases in separate circuit courts, creating an inconsistency between different parts of the United States. This creates a split decision among the circuit courts. Often, if there is a split decision between two or more circuits, and a related case is petitioned to the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court will take that case as to resolve the split.

Attorneys

[edit]In order to serve as counsel in a case appealed to a circuit court, the attorney must first be admitted to the bar of that circuit. Admission to the bar of a circuit court is granted as a matter of course to any attorney who is admitted to practice law in any state of the United States. The attorney submits an application, pays a fee, and takes the oath of admission. Local practice varies as to whether the oath is given in writing or in open court before a judge of the circuit, and most courts of appeals allow the applicant attorney to choose which method he or she prefers.

Nomenclature

[edit]When the courts of appeals were created in 1891, one was created for each of the nine circuits then existing, and each court was named the "United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the _____ Circuit". When a court of appeals was created for the District of Columbia in 1893, it was named the "Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia", and it was renamed to the "United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia" in 1934. In 1948, Congress renamed all of the courts of appeals then existing to their current formal names: the court of appeals for each numbered circuit was named the "United States Court of Appeals for the _____ Circuit", and the "United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia" became the "United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit". The Tenth Circuit was created in 1929 by subdividing the existing Eighth Circuit, and the Eleventh Circuit was created in 1981 by subdividing the existing Fifth Circuit. The Federal Circuit was created in 1982 by the merger of the United States Court of Customs and Patent Appeals and the appellate division of the United States Court of Claims.

Judicial councils

[edit]Judicial councils are panels in each circuit that are charged with making "necessary and appropriate orders for the effective and expeditious administration of justice" within their circuits.[19][20] Among their responsibilities is judicial discipline, the formulation of circuit policy, the implementation of policy directives received from the Judicial Conference of the United States, and the annual submission of a report to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts on the number and nature of orders entered during the year that relate to judicial misconduct.[19][21] Judicial councils consist of the chief judge of the circuit and an equal number of circuit judges and district judges of the circuit.[19][22]

Circuit composition

[edit]

The courts of appeals, and the lower courts and specific other bodies over which they have appellate jurisdiction, are as follows:

- Notes

- ^ a b c These are article IV territorial courts and are therefore not part of the federal judiciary.

- ^ a b c These are article I tribunals and are therefore not part of the federal judiciary.

- ^ The Federal Circuit also has appellate jurisdiction over certain claims filed in any district court.

- ^ a b c d e f g h These are administrative bodies within the executive branch and are therefore not part of the federal judiciary.

- ^ This is an administrative body within the legislative branch and therefore not part of the federal judiciary.

Circuit population

[edit]Based on 2020 United States census figures, the population residing in each circuit is as follows.[23][24]

| Circuit | Supervising justice[25] | Authorized judges | Population | Percentage of US population | Population per authorized judge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.C. Circuit | Roberts | 11 | 689,545 | 0.21% | 62,685 |

| 1st Circuit | Jackson | 6 | 14,153,058 | 4.23% | 2,358,843 |

| 2nd Circuit | Sotomayor | 13 | 24,450,270 | 7.30% | 1,880,790 |

| 3rd Circuit | Alito | 14 | 23,368,788 | 6.98% | 1,669,199 |

| 4th Circuit | Roberts | 15 | 32,160,146 | 9.61% | 2,144,010 |

| 5th Circuit | Alito | 17 | 36,764,541 | 10.97% | 2,162,620 |

| 6th Circuit | Kavanaugh | 16 | 33,293,455 | 9.94% | 2,080,841 |

| 7th Circuit | Barrett | 11 | 25,491,754 | 7.60% | 2,317,432 |

| 8th Circuit | Kavanaugh | 11 | 21,690,565 | 6.47% | 1,971,870 |

| 9th Circuit | Kagan | 29 | 67,050,034 | 20.01% | 2,312,070 |

| 10th Circuit | Gorsuch | 12 | 18,636,936 | 5.56% | 1,553,078 |

| 11th Circuit | Thomas | 12 | 37,274,374 | 11.13% | 3,106,198 |

| Federal Circuit[Note 1] | Roberts | 12 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 9 [Note 2] | 179 | 335,023,466[Note 3][26] | 100% | ~1,871,639 |

- Notes

- ^ Per 28 U.S.C. § 1295 - The Federal Circuit's jurisdiction is not based on geography; rather, the Federal Circuit has jurisdiction over the entire United States, for certain classes of cases.

- ^ Per 28 U.S.C. § 42 - A justice may be assigned to more than one circuit, and two or more justices may be assigned to the same circuit.

- ^ This figure includes the 50 states, D.C., Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands, even though the latter two's district courts are not federal courts per se as noted above. The Federal appeals process has never been codified in American Samoa, and matters of federal law arising in American Samoa have generally been adjudicated in U.S. district courts in Hawaii or the District of Columbia. see also : GAO-08-1124T

History

[edit]The Judiciary Act of 1789 established three circuits, which were groups of judicial districts in which United States circuit courts were established.[27] The original three circuits were given distinct names, rather than numbers: the Eastern, the Middle, and the Southern.[27] Each circuit court consisted of two Supreme Court justices and the local district judge; the three circuits existed solely for the purpose of assigning the justices to a group of circuit courts. Some districts (generally the ones most difficult for an itinerant justice to reach) did not have a circuit court; in these districts the district court exercised the original jurisdiction of a circuit court. As new states were admitted to the Union, Congress often did not create circuit courts for them for a number of years.

The number of circuits remained unchanged until the year after Rhode Island ratified the Constitution, when the Midnight Judges Act reorganized the districts into six numbered circuits, and created circuit judgeships so that Supreme Court justices would no longer have to ride circuit. This Act, however, was repealed in March 1802, and Congress provided that the former circuit courts would be revived as of July 1 of that year. But it then passed the new Judiciary Act of 1802 in April, so that the revival of the old courts never took effect. The 1802 Act restored circuit riding, but with only one justice to a circuit; it therefore created six new circuits, but with slightly different compositions than the 1801 Act. These six circuits later were augmented by others. Until 1866, each new circuit (except the short-lived California Circuit) was accompanied by a newly created Supreme Court seat.

| State | Judicial District(s) created | Circuit assignment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| New Hampshire | 1789 | Eastern, 1789–1801 1st, 1801– |

| Massachusetts | 1789 | Eastern, 1789–1801 1st, 1801– |

| Maine | 1789[Note 1] | Eastern, 1789–1801 1st, 1801–1820 1st, 1820– |

| Rhode Island | 1790 | Eastern, 1790–1801 1st, 1801– |

| Connecticut | 1789 | Eastern, 1789–1801 2nd, 1801– |

| New York | 1789 | Eastern, 1789–1801 2nd, 1801– |

| New Jersey | 1789 | Middle, 1789–1801 3rd, 1801– |

| Pennsylvania | 1789 | Middle, 1789–1801 3rd, 1801– |

| Delaware | 1789 | Middle, 1789–1801 3rd, 1801–1802 4th, 1802–1866 3rd, 1866– |

| Maryland | 1789 | Middle, 1789–1801 4th, 1801– |

| Virginia | 1789 | Middle, 1789–1801 4th, 1801–1802 5th, 1802–1842 4th, 1842– |

| Kentucky | 1789[Note 2] | 6th, 1801–1802 7th, 1807–1837 8th, 1837–1863 6th, 1863– |

| North Carolina | 1790 | Southern, 1790–1801 5th, 1801–1842 6th, 1842–1863 4th, 1863– |

| South Carolina | 1789 | Southern, 1789–1801 5th, 1801–1802 6th, 1802–1863 5th, 1863–1866 4th, 1866– |

| Georgia | 1789 | Southern, 1789–1801 5th, 1801–1802 6th, 1802–1863 5th, 1863–1981 11th, 1981– |

| Vermont | 1791 | Eastern, 1791–1801 2nd, 1801– |

| Tennessee | 1796 | 6th, 1801–1802 7th, 1807–1837 8th, 1837–1863 6th, 1863– |

| Ohio | 1801 (abolished 1802)[Note 3] | 6th, 1801–1802 |

| Ohio | 1803 | 7th, 1807–1866 6th, 1866– |

| Louisiana | 1812 | 9th, 1837–1842 (Eastern District) 5th, 1842–1863 6th, 1863–1866 5th, 1866– |

| Indiana | 1816 | 7th, 1837– |

| Mississippi | 1817 | 9th, 1837–1863 5th, 1863– |

| Illinois | 1818 | 7th, 1837–1863 8th, 1863–1866 7th, 1866– |

| Alabama | 1819 | 9th, 1837–1842 5th, 1842–1981 11th, 1981– |

| Missouri | 1821 | 8th, 1837–1863 9th, 1863–1866 8th, 1866– |

| Arkansas | 1836 | 9th, 1837–1851 9th, 1851–1863 (Eastern District) 6th, 1863–1866 (Eastern District) 8th, 1866– |

| Michigan | 1837 | 7th, 1837–1863 8th, 1863–1866 6th, 1866– |

| Florida | 1845 | 5th, 1863–1981 11th, 1981– |

| Texas | 1845 | 6th, 1863–1866 5th, 1866– |

| Iowa | 1846 | 9th, 1863–1866 8th, 1866– |

| Wisconsin | 1848 | 8th, 1863–1866 7th, 1866– |

| California | 1850 | California Circuit, 1855–1863 10th, 1863–1866 9th, 1866– |

| Minnesota | 1858 | 9th, 1863–1866 8th, 1866– |

| Oregon | 1859 | 10th, 1863–1866 9th, 1866– |

| Kansas | 1861 | 9th, 1863–1866 8th, 1866–1929 10th, 1929– |

| West Virginia | 1863 | 4th, 1863– |

| Nevada | 1864 | 9th, 1866– |

| Nebraska | 1867 | 8th, 1867– |

| Colorado | 1876 | 8th, 1876–1929 10th, 1929– |

| North Dakota | 1889 | 8th, 1889– |

| South Dakota | 1889 | 8th, 1889– |

| Montana | 1889 | 9th, 1889– |

| Washington | 1889 | 9th, 1889– |

| Idaho | 1890 | 9th, 1890– |

| Wyoming | 1890 | 8th, 1890–1929 10th, 1929– |

| Utah | 1896 | 8th, 1896–1929 10th, 1929– |

| Oklahoma | 1907 | 8th, 1907–1929 10th, 1929– |

| New Mexico | 1912 | 8th, 1912–1929 10th, 1929– |

| Arizona | 1912 | 9th, 1912– |

| District of Columbia | 1948[Note 4] | District of Columbia Circuit, 1948– |

| Alaska | 1959 | 9th, 1959– |

| Hawaii | 1959 | 9th, 1959– |

| Puerto Rico | 1966[Note 5] | 1st, 1966– |

See also

[edit]- District of Columbia Court of Appeals, a federally established appellate court that is not considered a U.S. court of appeals

- Judicial appointment history for United States federal courts

- List of current United States circuit judges

- List of United States courts of appeals cases

- State supreme court

- United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, an Article I tribunal that hears appeals of court-martial decisions

- United States Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, an Article I tribunal that reviews decisions of the Board of Veterans' Appeals

- United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided Massachusetts into the Maine District, comprising what is now the State of Maine, and the Massachusetts District, comprising the remainder of the state.

- ^ The Judiciary Act of 1789 divided Virginia into the Kentucky District, comprising what is now the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and the Virginia District, comprising the remainder of the state.

- ^ The first District of Ohio encompassed the Northwest and Indiana Territories.

- ^ The pre-existing courts of the District of Columbia were elevated to United States district court and court of appeals status in 1948. The courts of the District had been incorporated into the Federal Court System by the Judiciary Act of 1925.

- ^ The pre-existing territorial district court of Puerto Rico was elevated to United States district court status. Appellate jurisdiction from the Puerto Rico courts was assigned to the 1st Circuit in 1915.

References

[edit]- ^ The assignment of judicial circuits is defined by 28 U.S.C. § 41, along with 48 U.S.C. § 1821 which specifies that the Northern Mariana Islands falls within the same judicial circuit as Guam.

- ^ Brian Duignan, Gloria Lotha (July 20, 1998). "United States Court of Appeals". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Department of Justice. "Introduction To The Federal Court System". Executive Office for United States Attorneys.

- ^ "Court Role and Structure". Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts on behalf of the Federal Judiciary.

- ^

"The Supreme Court at Work: The Term and Caseload". United States Supreme Court. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

Plenary review, with oral arguments by attorneys, is granted in about 80 of those cases each Term, and the Court typically disposes of about 100 or more cases without plenary review.

- ^ Judicial Compensation U.S. Courts. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ The U.S. Courts of Appeals and the Federal Judiciary, History of the Federal Judiciary, Federal Judicial Center (last visited March 5, 2014).

- ^ See e.g. "IOP 35.1. En Banc Poll and Decision". United States Court of Appeals 2nd Circuit. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Rule 35-3 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Ninth Circuit Rules. http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/uploads/rules/frap.pdf

- ^ United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974)

- ^ United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005)

- ^ Aaron Nielson, "The Death of the Supreme Court's Certified Question Jurisdiction", 59 Cath. U. L. Rev. 483 (2010).

- ^ "US v. Penaranda, 375 F. 3d 238 - Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit 2004". Google Scholar. Archived from the original on September 19, 2023.

- ^ Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004)

- ^ "United States v. Penaranda, 543 U.S. 1117". Casetext.

- ^ "City of Mesquite v. Aladdin's Castle, Inc., 455 US 283 - Supreme Court 1982". Google Scholar. Archived from the original on August 1, 2022.

- ^ "28 U.S. Code § 158 - Appeals". Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023.

- ^ Bradley v. Richmond Sch. Bd., 416 U.S. 696, 711-12 (1974)

- ^ a b c Barbour, Emily C. (April 7, 2011), Judicial Discipline Process: An Overview (PDF), Congressional Research Service

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 332

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 332(g)

- ^ 28 U.S.C. § 332(1)(a)

- ^ US Census Bureau. "2020 Population and Housing State Data". Census.gov. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ US Circuit Courts. "Geographic Boundaries of US Courts of Appeals and US District Courts" (PDF).

- ^ Supreme Court of the United States. "Circuit Assignments". supremecourt.gov. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ "GAO-08-1124T" (PDF). www.gao.gov. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ a b White, G. Edward (2012). Law in American History, Volume 1: From the Colonial Years Through the Civil War. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780190634940. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

KSF

KSF