United Tribes of New Zealand

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

United Tribes of New Zealand Te W(h)akaminenga o Nga Rangatiratanga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tireni | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1835–1840 | |||||||||

New Zealand in 1832 | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||

| Capital | Waitangi | ||||||||

| Common languages | Māori, English | ||||||||

| Government | Confederation | ||||||||

| Hereditary chiefs and heads of tribes | |||||||||

• 1835–1840 | Northern chiefs | ||||||||

| British Resident | |||||||||

• 1835–1840 | James Busby | ||||||||

| Legislature | Congress at Waitangi | ||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial period | ||||||||

| 1835 | |||||||||

| 1840 | |||||||||

• Colony of New Zealand | 1841 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | New Zealand | ||||||||

The United Tribes of New Zealand (Māori: Te W(h)akaminenga o Ngā Rangatiratanga o Ngā Hapū o Nū Tīreni) was a confederation of Māori tribes based in the north of the North Island, existing legally from 1835 to 1840. It received diplomatic recognition from the United Kingdom, which shortly thereafter proclaimed the foundation of the Colony of New Zealand upon the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

History

[edit]This article appears to contradict the article Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand. |

The confederation was convened in 1834 by British Resident James Busby. Busby had been sent to New Zealand in 1833 by the Colonial Office to serve as the official British Resident, and was anxious to set up a framework for trade between Māori and Europeans. The Māori chiefs of the northern part of the North Island agreed to meet with him in March 1834. Rumours began spreading that the Frenchman Baron Charles de Thierry planned to set up an independent state at Hokianga. The United Tribes declared their independence on 28 October 1835 with the signing of the Declaration of Independence.[1] In 1836, the British Crown under King William IV recognised the United Tribes and its flag.

By 1839, the Declaration of the United Tribes had 52 signatories from Northland and a few signatories from other parts, notably from the ariki of the Waikato Tainui, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero.[2] In February 1840, a number of chiefs of the United Tribes convened at Waitangi to sign the Treaty of Waitangi.[3] During the Musket Wars (1807–1842), Ngāpuhi and other tribes raided and occupied many parts of the North Island, but eventually reverted to their previous territorial status as other tribes acquired European weapons.[citation needed]

From a New Zealand standpoint under the settler government, the Confederation has been considered to have been assimilated into a new entity after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi; the Declaration is viewed in large part as merely a historical document.[1] In recent times, questions have arisen regarding the constitutional relevance of the Declaration.[4]

New Zealand Company use of United Tribes flag

[edit]In 1840 the New Zealand Company raised the flag of the United Tribes at their settlement in Port Nicholson (Wellington),[5] proclaiming government by "colonial council" that claimed to derive its powers from authority granted by local chiefs. Interpreting the moves as "high treason", Governor William Hobson declared British sovereignty over the entirety of the North Island on 21 May 1840,[6] and on 23 May declared the council illegal.[7] He then despatched his Colonial Secretary, Willoughby Shortland, with 30 soldiers and six mounted police on 30 June 1840,[5] to Port Nicholson to tear down the flag. Shortland commanded the residents to withdraw from their "illegal association" and to submit to the representatives of the Crown.[8]

Modern developments

[edit]As of October 2010, the Waitangi Tribunal began investigating the claim by Ngāpuhi that their sovereignty was not ceded in their signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.[9] The Tribunal, in Te Paparahi o te Raki inquiry (Wai 1040)[10] is in the process of considering the Māori and Crown understandings of He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga / The Declaration of Independence 1835 and Te Tiriti o Waitangi / the Treaty of Waitangi 1840.

The first stage of the report was released in November 2014,[11][12] and found that Māori chiefs never agreed to give up their sovereignty when they signed the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.[13][14][15] Tribunal manager Julie Tangaere said at the report's release to the Ngapuhi claimants:

"Your tupuna [ancestors] did not give away their mana at Waitangi, at Waimate, at Mangungu. They did not cede their sovereignty. This is the truth you have been waiting a long time to hear."[16]

While final submissions were received in May 2018, the second stage of the report was still in the process of being written up as of October 2020.[17][needs update?]

Flag

[edit]

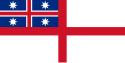

Busby asked Reverend Williams and the Colonial Secretary Richard Bourke in New South Wales to draw up three flags. On 20 March 1834, the three designs were put to 25 northern Maori chiefs at Waitangi by Busby and Captain Lambert of the man-of-war HMS Alligator. By a vote of 12–10–3, the design now widely known as the United Tribes Flag was chosen.[18] British, American, and French representatives witnessed the ceremony, which included a 13-gun salute from the Alligator.[19][20]

The flag selected was based in part on the St George's Cross that was already used by the Church Missionary Society, with a canton featuring a smaller red cross on a blue background fimbriated in black, and with a white eight-pointed star in each quarter of the canton.[21] When officially gazetted in New South Wales in August 1835, the description did not mention the fimbriation or the number of points on the stars.[22] The description was: "A red St. George's Cross on a white ground. In the first quarter, a red St. George's Cross on a blue ground, pierced with four white stars."[23] This version of the flag served as the de facto national flag of New Zealand from 1835 until the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in February 1840,[24] although the United Tribes flag continued to be used as a New Zealand flag after the Treaty, for example the flag features on the medals presented to soldiers who served in the South African War (1899–1902).[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b New Zealand Historical Atlas. p. "Te Whenua Rangatira", plate 36.

- ^ "Treaty events 1800–49 – Treaty timeline". New Zealand History online. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- ^ "Declaration of Independence – background to the Treaty". The Declaration of Independence. New Zealand History online. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ a b "New Zealand Company / United Tribes flag". Te Papa. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation of Sovereignty over the North Island 1840 [1840] NZConLRes 9". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. 21 May 1840. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation on the Illegal Assumption of Authority in the Port Nicholson District 1840 [1840] NZConLRes 11". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. 23 May 1840. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Burns, Patricia (1989). Fatal Success: A History of the New Zealand Company. Heinemann Reed. ISBN 0-7900-0011-3.

- ^ Field, Michael (9 May 2010). "Hearing starts into Ngāpuhi's claims". Stuff. Fairfax New Zealand. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ "Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) inquiry, Waitangi Tribunal". Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Report on Stage 1 of the Te Paparahi o Te Raki Inquiry Released". Waitangi Tribunal. 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Te Manutukutuku (Issue 67)". Waitangi Tribunal. February 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015

- ^ Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) (Wai 1040) Volume 1" (PDF). Waitangi Tribunal. 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ "Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) (Wai 1040) Volume 2" (PDF). Waitangi Tribunal. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015

- ^ He Whakaputanga me te Tiriti / The Declaration and the Treaty - Report Summary". Waitangi Tribunal. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Ngapuhi 'never gave up sovereignty'". The Northland Age. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Te Paparahi o Te Raki". waitangitribunal.govt.nz. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "United Tribes flag". NZHistory. Ministry of Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ John Butler, Compiled by R. J. Barton (1927). Earliest New Zealand: the Journals and Correspondence of the Rev. John Butler. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 404.

- ^ "History", united-tribes.com. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Pollock, Kerryn (13 July 2012). "Flags – New Zealand flag". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ Kingsley, Gavin (2000). "Te Hakituatahi ō Aotearoa (The First Flag of New Zealand)". Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ M'Leay, Alex. (25 August 1835). "New Zealand". The Australian. p. 4.

- ^ "New Zealand – Flag of the United Tribes (1835–1840)". Flags of the World. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ "South African War medal". NZHistory. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

KSF

KSF