Uralic languages

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 36 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 36 min

| Uralic | |

|---|---|

| Uralian | |

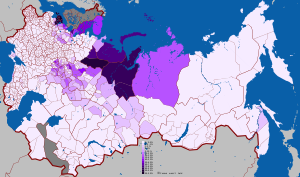

| Geographic distribution | Central Europe, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, and Northern Asia |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Uralic |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-5 | urj |

| Glottolog | ural1272 |

| |

The Uralic languages (/jʊəˈrælɪk/ yoor-AL-ik), sometimes called the Uralian languages (/jʊəˈreɪliən/ yoor-AY-lee-ən),[3] are spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian (which alone accounts for approximately 60% of speakers), Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation. Still smaller minority languages are Sámi languages of the northern Fennoscandia; other members of the Finnic languages, ranging from Livonian in northern Latvia to Karelian in northwesternmost Russia; and the Samoyedic languages, Mansi and Khanty spoken in Western Siberia.

The name Uralic derives from the family's purported "original homeland" (Urheimat) hypothesized to have been somewhere in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains, and was first proposed by Julius Klaproth in Asia Polyglotta (1823).[4][5]

Finno-Ugric is sometimes used as a synonym for Uralic,[6] though Finno-Ugric is widely understood to exclude the Samoyedic languages.[7] Scholars who do not accept the traditional notion that Samoyedic split first from the rest of the Uralic family may treat the terms as synonymous.[8]

Uralic languages are known for their often complex case systems and vowel harmony.

Origin and evolution

[edit]Homeland

[edit]Proposed homelands of the Proto-Uralic language include:

- The vicinity of the Volga River, west of the Urals, close to the Urheimat of the Indo-European languages, or to the east and southeast of the Urals. Historian Gyula László places its origin in the forest zone between the Oka River and central Poland. E.N. Setälä and M. Zsirai place it between the Volga and Kama Rivers. According to E. Itkonen, the ancestral area extended to the Baltic Sea. Jaakko Häkkinen identifies Proto-Uralic with Eneolithic Garino-Bor (Turbin) culture 3,000–2,500 YBP, located in the Lower Kama Basin.[9]

- Péter Hajdú has suggested a homeland in western and northwestern Siberia.[10][11]

- Juha Janhunen suggests a homeland in between the Ob and Yenisei drainage basins in Central Siberia.[12]

- By using linguistic, paleoclimatic and archaeological data, a group of scholars around Grünthal et al. (2022), including Juha Janhunen, traced back the Proto-Uralic homeland to a region East of the Urals, in Siberia, specifically somewhere close to the Minusinsk Basin, and reject a homeland in the Volga / Kama region. They further noted that a number of traits of Uralic are

- "distinctive in western Eurasia. ... typological properties are eastern-looking overall, fitting comfortably into northeast Asia, Siberia, or the North Pacific Rim".[13]

- Uralic-speakers may have spread westwards with the Seima-Turbino route.[14]

History of Uralic linguistics

[edit]Early attestations

[edit]The first plausible mention of a people speaking a Uralic language is in Tacitus's Germania (c. 98 AD),[15] mentioning the Fenni (usually interpreted as referring to the Sámi) and two other possibly Uralic tribes living in the farthest reaches of Scandinavia. There are many possible earlier mentions, including the Iyrcae (perhaps related to Yugra) described by Herodotus living in what is now European Russia, and the Budini, described by Herodotus as notably red-haired (a characteristic feature of the Udmurts) and living in northeast Ukraine and/or adjacent parts of Russia. In the late 15th century, European scholars noted the resemblance of the names Hungaria and Yugria, the names of settlements east of the Ural. They assumed a connection but did not seek linguistic evidence.[16]

Uralic studies

[edit]

The affinity of Hungarian and Finnish was first proposed in the late 17th century. Three candidates can be credited for the discovery: the German scholar Martin Fogel, the Swedish scholar Georg Stiernhielm, and the Swedish courtier Bengt Skytte. Fogel's unpublished study of the relationship, commissioned by Cosimo III of Tuscany, was clearly the most modern of these: he established several grammatical and lexical parallels between Finnish and Hungarian as well as Sámi. Stiernhielm commented on the similarities of Sámi, Estonian, and Finnish, and also on a few similar words between Finnish and Hungarian.[17][18] These authors were the first to outline what was to become the classification of the Finno-Ugric, and later Uralic family. This proposal received some of its initial impetus from the fact that these languages, unlike most of the other languages spoken in Europe, are not part of what is now known as the Indo-European family. In 1717, the Swedish professor Olof Rudbeck proposed about 100 etymologies connecting Finnish and Hungarian, of which about 40 are still considered valid.[19] Several early reports comparing Finnish or Hungarian with Mordvin, Mari or Khanty were additionally collected by Gottfried Leibniz and edited by his assistant Johann Georg von Eckhart.[20]

In 1730, Philip Johan von Strahlenberg published his book Das Nord- und Ostliche Theil von Europa und Asia (The Northern and Eastern Parts of Europe and Asia), surveying the geography, peoples and languages of Russia. All the main groups of the Uralic languages were already identified here.[21] Nonetheless, these relationships were not widely accepted. Hungarian intellectuals especially were not interested in the theory and preferred to assume connections with Turkic tribes, an attitude characterized by Merritt Ruhlen as due to "the wild unfettered Romanticism of the epoch".[22] Still, in spite of this hostile climate, the Hungarian Jesuit János Sajnovics traveled with Maximilian Hell to survey the alleged relationship between Hungarian and Sámi, while they were also on a mission to observe the 1769 Venus transit. Sajnovics published his results in 1770, arguing for a relationship based on several grammatical features.[23] In 1799, the Hungarian Sámuel Gyarmathi published the most complete work on Finno-Ugric to that date.[24]

Up to the beginning of the 19th century, knowledge of the Uralic languages spoken in Russia had remained restricted to scanty observations by travelers. Already the Finnish historian Henrik Gabriel Porthan had stressed that further progress would require dedicated field missions.[25] One of the first of these was undertaken by Anders Johan Sjögren, who brought the Vepsians to general knowledge and elucidated in detail the relatedness of Finnish and Komi.[26] Still more extensive were the field research expeditions made in the 1840s by Matthias Castrén (1813–1852) and Antal Reguly (1819–1858), who focused especially on the Samoyedic and the Ob-Ugric languages, respectively. Reguly's materials were worked on by the Hungarian linguist Pál Hunfalvy (1810–1891) and German Josef Budenz (1836–1892), who both supported the Uralic affinity of Hungarian.[27] Budenz was the first scholar to bring this result to popular consciousness in Hungary and to attempt a reconstruction of the Proto-Finno-Ugric grammar and lexicon.[28] Another late-19th-century Hungarian contribution is that of Ignácz Halász (1855–1901), who published extensive comparative material of Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic in the 1890s,[29][30][31][32] and whose work is at the base of today's wide acceptance of the inclusion of Samoyedic as a part of the Uralic family.[33] Meanwhile, in the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, a chair for Finnish language and linguistics at the University of Helsinki was created in 1850, first held by Castrén.[34]

In 1883, the Finno-Ugrian Society was founded in Helsinki on the proposal of Otto Donner, which would lead to Helsinki overtaking St. Petersburg as the chief northern center of research of the Uralic languages.[35] During the late 19th and early 20th century (until the separation of Finland from Russia following the Russian Revolution), the Society hired many scholars to survey the still less-known Uralic languages. Major researchers of this period included Heikki Paasonen (studying especially the Mordvinic languages), Yrjö Wichmann (studying Permic), Artturi Kannisto (Mansi), Kustaa Fredrik Karjalainen (Khanty), Toivo Lehtisalo (Nenets), and Kai Donner (Kamass).[36] The vast amounts of data collected on these expeditions would provide over a century's worth of editing work for later generations of Finnish Uralicists.[37]

Classification

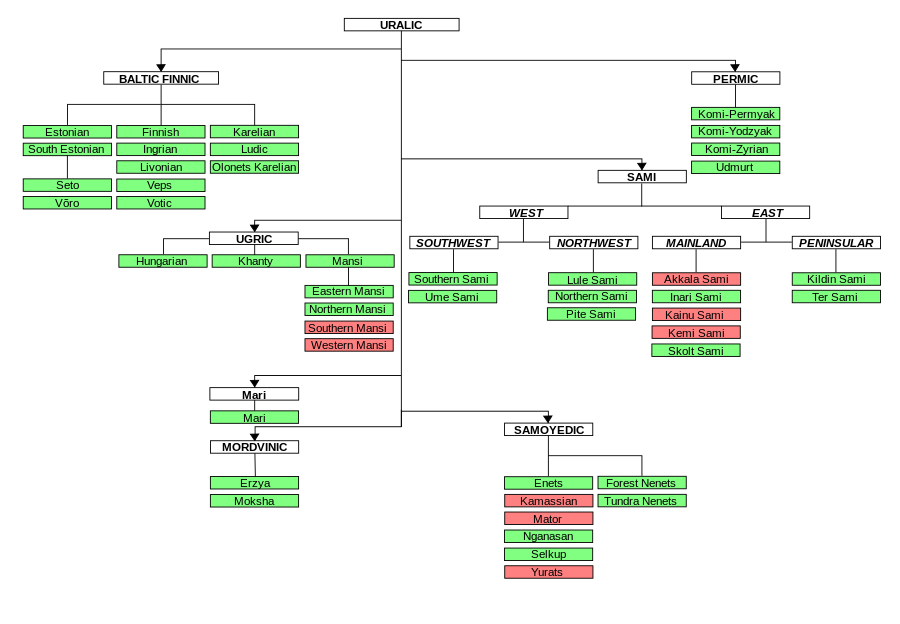

[edit]The Uralic family comprises nine undisputed groups with no consensus classification between them. (Some of the proposals are listed in the next section.) An agnostic approach treats them as separate branches.[39][40]

Obsolete or native names are displayed in italics.

- Sámi (Sami, Saami, Samic, Saamic, Lappic, Lappish)

- Finnic (Fennic, Baltic Finnic, Balto-Finnic, Balto-Fennic)

- Mordvinic (Mordvin, Mordvinian)

- Mari (Cheremis)

- Permic (Permian)

- Hungarian (Magyar)

- Mansi (Vogul, Ма̄ньси, Маньсь)

- Khanty (Ostyak, Handi, Hantõ, Хӑнты, Ӄӑнтәӽ)

- Samoyedic (Samoyed)

There is also historical evidence of a number of extinct languages of uncertain affiliation:

- Merya

- Muromian

- Meshcherian (until 16th century?)

Traces of Finno-Ugric substrata, especially in toponymy, in the northern part of European Russia have been proposed as evidence for even more extinct Uralic languages.[41]

Traditional classification

[edit]All Uralic languages are thought to have descended, through independent processes of language change, from Proto-Uralic. The internal structure of the Uralic family has been debated since the family was first proposed.[42] Doubts about the validity of most or all of the proposed higher-order branchings (grouping the nine undisputed families) are becoming more common.[42][43][8]

A traditional classification of the Uralic languages has existed since the late 19th century.[44] It has enjoyed frequent adaptation in whole or in part in encyclopedias, handbooks, and overviews of the Uralic family. Otto Donner's model from 1879 is as follows:

- Uralic

- Ugric (Ugrian)

- Finno-Permic (Permian-Finnic)

- Permic

- Finno-Volgaic (Finno-Cheremisic, Finno-Mari)

- Volgaic

- Finno-Samic (Finno-Saamic, Finno-Lappic)

At Donner's time, the Samoyedic languages were still poorly known, and he was not able to address their position. As they became better known in the early 20th century, they were found to be quite divergent, and they were assumed to have separated already early on. The terminology adopted for this was "Uralic" for the entire family, "Finno-Ugric" for the non-Samoyedic languages (though "Finno-Ugric" has, to this day, remained in use also as a synonym for the whole family). Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic are listed in ISO 639-5 as primary branches of Uralic.

The following table lists nodes of the traditional family tree that are recognized in some overview sources.

| Year | Author(s) | Finno- Ugric |

Ugric | Ob-Ugric | Finno- Permic |

Finno- Volgaic |

Volga- Finnic |

Finno- Samic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | Szinnyei[45] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 1921 | T. I. Itkonen[46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 1926 | Setälä[47] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 1962 | Hajdú[48][49] | ✓ | ✗[a] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗[a] | ✗ |

| 1965 | Collinder[19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 1966 | E. Itkonen[50] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 1968 | Austerlitz[51] | ✗[b] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗[b] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| 1977 | Voegelin & Voegelin[52] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2002 | Kulonen[53] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 2002 | Michalove[54] | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ||

| 2007 | Häkkinen[55] | ✗ | ✗[c] | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗[c] |

| 2007 | Lehtinen[56] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 2007 | Salminen[39] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 2009 | Janhunen[12] | ✓ | ✗[d] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗? |

- a. Hajdú describes the Ugric and Volgaic groups as areal units.

- b. Austerlitz accepts narrower-than-traditional Finno-Ugric and Finno-Permic groups that exclude Sámi

- c. Häkkinen groups Hungarian, Ob-Ugric and Samoyed into a Ugro-Samoyed branch, and groups Balto-Finnic, Sámi and Mordvin into a Finno-Mordvin branch

- d. Janhunen accepts a reduced Ugric branch, called 'Mansic', that includes Hungarian and Mansi

Little explicit evidence has however been presented in favour of Donner's model since his original proposal, and numerous alternate schemes have been proposed. Especially in Finland, there has been a growing tendency to reject the Finno-Ugric intermediate protolanguage.[43][57] A recent competing proposal instead unites Ugric and Samoyedic in an "East Uralic" group for which shared innovations can be noted.[58]

The Finno-Permic grouping still holds some support, though the arrangement of its subgroups is a matter of some dispute. Mordvinic is commonly seen as particularly closely related to or part of Finno-Samic.[59] The term Volgaic (or Volga-Finnic) was used to denote a branch previously believed to include Mari, Mordvinic and a number of the extinct languages, but it is now obsolete[43] and considered a geographic classification rather than a linguistic one.

Within Ugric, uniting Mansi with Hungarian rather than Khanty has been a competing hypothesis to Ob-Ugric.

Lexical isoglosses

[edit]Lexicostatistics has been used in defense of the traditional family tree. A recent re-evaluation of the evidence[54] however fails to find support for Finno-Ugric and Ugric, suggesting four lexically distinct branches (Finno-Permic, Hungarian, Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic).

One alternative proposal for a family tree, with emphasis on the development of numerals, is as follows:[12]

- Uralic (*kektä "2", *wixti "5" / "10")

- Samoyedic (*op "1", *ketä "2", *näkur "3", *tettə "4", *səmpəleŋkə "5", *məktut "6", *sejtwə "7", *wiət "10")

- Finno-Ugric (*üki/*ükti "1", *kormi "3", *ńeljä "4", *wiiti "5", *kuuti "6", *luki "10")

- Mansic

- Mansi

- Hungarian (hét "7"; replacement egy "1")

- Finno-Khantic (reshaping *kolmi "3" on the analogy of "4")

- Khanty

- Finno-Permic (reshaping *kektä > *kakta)

- Permic

- Finno-Volgaic (*śećem "7")

- Mari

- Finno-Saamic (*kakteksa, *ükteksa "8, 9")

- Saamic

- Finno-Mordvinic (replacement *kümmen "10" (*luki- "to count", "to read out"))

- Mordvinic

- Finnic

- Mansic

Phonological isoglosses

[edit]Another proposed tree, more divergent from the standard, focusing on consonant isoglosses (which does not consider the position of the Samoyedic languages) is presented by Viitso (1997),[60] and refined in Viitso (2000):[61]

- Finno-Ugric

- Saamic–Fennic (consonant gradation)

- Saamic

- Fennic

- Eastern Finno-Ugric

- Mordva

- (node)

- Mari

- Permian–Ugric (*δ > *l)

- Permian

- Ugric (*s *š *ś > *ɬ *ɬ *s)

- Hungarian

- Khanty

- Mansi

- Saamic–Fennic (consonant gradation)

The grouping of the four bottom-level branches remains to some degree open to interpretation, with competing models of Finno-Saamic vs. Eastern Finno-Ugric (Mari, Mordvinic, Permic-Ugric; *k > ɣ between vowels, degemination of stops) and Finno-Volgaic (Finno-Saamic, Mari, Mordvinic; *δʲ > *ð between vowels) vs. Permic-Ugric. Viitso finds no evidence for a Finno-Permic grouping.

Extending this approach to cover the Samoyedic languages suggests affinity with Ugric, resulting in the aforementioned East Uralic grouping, as it also shares the same sibilant developments. A further non-trivial Ugric-Samoyedic isogloss is the reduction *k, *x, *w > ɣ when before *i, and after a vowel (cf. *k > ɣ above), or adjacent to *t, *s, *š, or *ś.[58]

Finno-Ugric consonant developments after Viitso (2000); Samoyedic changes after Sammallahti (1988)[62]

| Saamic | Finnic | Mordvinic | Mari | Permic | Hungarian | Mansi | Khanty | Samoyedic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial lenition of *k | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Medial lenition of *p, *t | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | |

| Degemination | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Consonant gradation | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | yes* | |

| Development of | *δ | *ð | *t | *t | ∅ | *l | l | *l | *l | *r |

| *δʲ | *t, ∅ | *lʲ | ɟ ❬gy❭, j | *lʲ | *j | *j | ||||

| *s | *s | *s | *s, z | *s, z | *s, z | ∅ | *t | *ɬ | *t | |

| *š | *h | *š, ž | *š, ž | *š, ž | ||||||

| *ś | *č | *s | *ś, ź | *ś, ź | s ❬sz❭ | *s, š | *s | *s | ||

| *ć | *c | *ć, ź | č ❬cs❭ | *ć | ||||||

| *č | *c | *t | *č | *č | *č, ž | š ❬s❭ | *š | *č̣ | *č | |

- *Only present in Nganasan.

- Note: Proto-Uralic *ś becomes Proto-Sámi *č unless before a consonant, where it becomes *š, which, in the western Sámi languages, is vocalized to *j before a stop.

- Note: Proto-Mari *s and *š in only reliably stay distinct in the Malmyž dialect of Eastern Mari. Elsewhere, *s usually becomes *š.

- Note: Proto-Khanty *ɬ in many of the dialects yields *t; Häkkinen assumes this also happened in Mansi and Samoyedic.

The inverse relationship between consonant gradation and medial lenition of stops (the pattern also continuing within the three families where gradation is found) is noted by Helimski (1995): an original allophonic gradation system between voiceless and voiced stops would have been easily disrupted by a spreading of voicing to previously unvoiced stops as well.[63]

Honkola, et al. (2013)

[edit]A computational phylogenetic study by Honkola, et al. (2013)[64] classifies the Uralic languages as follows. Estimated divergence dates from Honkola, et al. (2013) are also given.

- Uralic (5300 YBP)

- Samoyedic

- Finno-Ugric (3900 YBP)

Typology

[edit]Structural characteristics generally said to be typical of Uralic languages include:

Grammar

[edit]- extensive use of independent suffixes (agglutination)

- a large set of grammatical cases marked with agglutinative suffixes (13–14 cases on average; mainly later developments: Proto-Uralic is reconstructed with 6 cases), e.g.:

- Erzya: 12 cases

- Estonian: 14 cases (15 cases with instructive)

- Finnish: 15 cases

- Hungarian: 18 cases (together 34 grammatical cases and case-like suffixes)

- Inari Sámi: 9 cases

- Komi: in certain dialects as many as 27 cases

- Moksha: 13 cases

- Nenets: 7 cases

- Northern Sámi: 6 cases

- Udmurt: 16 cases

- Veps: 24 cases

- Northern Mansi: 6 cases

- Eastern Mansi: 8 cases

- unique Uralic case system, from which all modern Uralic languages derive their case systems.

- nominative singular has no case suffix.

- accusative and genitive suffixes are nasal consonants (-n, -m, etc.)

- three-way distinction in the local case system, with each set of local cases being divided into forms corresponding roughly to "from", "to", and "in/at"; especially evident, e.g. in Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian, which have several sets of local cases, such as the "inner", "outer" and "on top" systems in Hungarian, while in Finnish the "on top" forms have merged to the "outer" forms.

- the Uralic locative suffix exists in all Uralic languages in various cases, e.g. Hungarian superessive, Finnish essive (-na), Northern Sámi essive, Erzyan inessive, and Nenets locative.

- the Uralic lative suffix exists in various cases in many Uralic languages, e.g. Hungarian illative, Finnish lative (-s as in ulos 'out' and rannemmas 'more towards the shore'), Erzyan illative, Komi approximative, and Northern Sámi locative.

- a lack of grammatical gender, including one pronoun for both he and she; for example, hän in Finnish, tämä in Votic, tämā or ta (short form for tämā) in Livonian,[65] tema or ta (short form for tema) in Estonian, сійӧ ([sijɘ]) in Komi, ő in Hungarian.

- negative verb, which exists in many Uralic languages (notably absent in Hungarian)

- use of postpositions as opposed to prepositions (prepositions are uncommon).

- possessive suffixes

- the genitive is also used to express possession in some languages, e.g. Estonian mu koer, colloquial Finnish mun koira, Northern Sámi mu beana 'my dog' (literally 'dog of me'). Separate possessive adjectives and possessive pronouns, such as my and your, are rare.

- dual, in the Samoyedic, Ob-Ugric and Sámi languages and reconstructed for Proto-Uralic

- plural markers -j (i) and -t (-d, -q) have a common origin (e.g. in Finnish, Estonian, Võro, Erzya, Sámi languages, Samoyedic languages). Hungarian, however, has -i- before the possessive suffixes and -k elsewhere. The plural marker -k is also used in the Sámi languages, but there is a regular merging of final -k and -t in Sámi, so it can come from either ending.

- Possessions are expressed by a possessor in the adessive or dative case, the verb "be" (the copula, instead of the verb "have") and the possessed with or without a possessive suffix. The grammatical subject of the sentence is thus the possessed. In Finnish, for example, the possessor is in the adessive case: "Minulla on kala", literally "At me is fish", i.e. "I have a fish", whereas in Hungarian, the possessor is in the dative case, but appears overtly only if it is contrastive, while the possessed has a possessive ending indicating the number and person of the possessor: "(Nekem) van egy halam", literally "(To me [dative]) is a fish-my" ("(For me) there is a fish of mine"), i.e. "(As for me,) I have a fish".

- expressions that include a numeral are singular if they refer to things which form a single group, e.g. "négy csomó" in Hungarian, "njeallje čuolmma" in Northern Sámi, "neli sõlme" in Estonian, and "neljä solmua" in Finnish, each of which means "four knots", but the literal approximation is "four knot". (This approximation is accurate only for Hungarian among these examples, as in Northern Sámi the noun is in the singular accusative/genitive case and in Finnish and Estonian the singular noun is in the partitive case, such that the number points to a part of a larger mass, like "four of knot(s)".)

Phonology

[edit]- Vowel harmony: this is present in many but by no means all Uralic languages. It exists in Hungarian and various Baltic-Finnic languages, and is present to some degree elsewhere, such as in Mordvinic, Mari, Eastern Khanty, and Samoyedic. It is lacking in Sámi, Permic, Selkup and standard Estonian, while it does exist in Võro and elsewhere in South Estonian, as well as in Kihnu Island subdialect of North Estonian.[66][67][68] (Although double dot diacritics are used in writing Uralic languages, the languages do not exhibit Germanic umlaut, a different type of vowel assimilation.)

- Large vowel inventories. For example, some Selkup varieties have over twenty different monophthongs, and Estonian has over twenty different diphthongs.

- Palatalization of consonants; in this context, palatalization means a secondary articulation, where the middle of the tongue is tense. For example, pairs like [ɲ] – [n], or [c] – [t] are contrasted in Hungarian, as in hattyú [hɒcːuː] "swan". Some Sámi languages, for example Skolt Sámi, distinguish three degrees: plain ⟨l⟩ [l], palatalized ⟨'l⟩ [lʲ], and palatal ⟨lj⟩ [ʎ], where ⟨'l⟩ has a primary alveolar articulation, while ⟨lj⟩ has a primary palatal articulation. Original Uralic palatalization is phonemic, independent of the following vowel and traceable to the millennia-old Proto-Uralic. It is different from Slavic palatalization, which is of more recent origin. The Finnic languages have lost palatalization, but several of them have reacquired it, so Finnic palatalization (where extant) was originally dependent on the following vowel and does not correlate to palatalization elsewhere in Uralic.

- Lack of phonologically contrastive tone.

- In many Uralic languages, the stress is always on the first syllable, though Nganasan shows (essentially) penultimate stress, and a number of languages of the central region (Erzya, Mari, Udmurt and Komi-Permyak) synchronically exhibit a lexical accent. The Erzya language can vary its stress in words to give specific nuances to sentential meaning.

Lexicography

[edit]Basic vocabulary of about 200 words, including body parts (e.g. eye, heart, head, foot, mouth), family members (e.g. father, mother-in-law), animals (e.g. viper, partridge, fish), nature objects (e.g. tree, stone, nest, water), basic verbs (e.g. live, fall, run, make, see, suck, go, die, swim, know), basic pronouns (e.g. who, what, we, you, I), numerals (e.g. two, five); derivatives increase the number of common words.

Selected cognates

[edit]The following is a very brief selection of cognates in basic vocabulary across the Uralic family, which may serve to give an idea of the sound changes involved. This is not a list of translations: cognates have a common origin, but their meaning may be shifted and loanwords may have replaced them.

| English | Proto-Uralic | Finnic | Sámi | Mordvin | Mari | Permic | Hungarian | Mansi | Khanty | Samoyed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finnish | Estonian | Võro | Southern Sámi | Northern Sámi | Kildin | Erzya | Meadow | Komi | Udmurt | Northern | Eastern | Southern | Kazym | Vakh | Tundra Nenets | |||

| 'fire' | *tule | tuli (tule-) | tuli (tule-) | tuli (tulõ-) | dålle [tolːə] |

dolla | то̄лл [toːlː] |

тол [tol] |

тул [tul] |

тыв (тыл-) [tɯʋ] ([tɯl-]) |

тыл [tɯl] |

tűz | - | тав, тов | (täuˈt) | тўт | tez | ту [tu] |

| 'water' | *wete | vesi (vete-) |

vesi (vee-) |

vesi (vii-) |

– | – | – | ведь [vedʲ] |

вӱд [βyd] |

ва [ʋa] |

ву [ʋu] |

víz | вит [βit] |

вить | (üt́) | – | – | иˮ [jiʔ] |

| 'ice' | *jäŋe | jää | jää | ijä | jïenge [jɨeŋə] |

jiekŋa | ӣӈӈ [jiːŋː] |

эй [ej] |

и [i] |

йи [ji] |

йӧ [jɘ] |

jég | я̄ӈк [jaːŋk] |

янгк | (ľɑ̄ŋ)/(ľäŋ) | йєӈк | jeŋk | – |

| 'fish' | *kala | kala | kala | kala | guelie [kʉelie] |

guolli | кӯлль [kuːlʲː] |

кал [kal] |

кол [kol] |

– | – | hal | хӯл [xuːl] |

хул | (kho̰l) | хўԓ | kul | халя [hʌlʲɐ] |

| 'nest' | *pesä | pesä | pesa | pesä | biesie [piesie] |

beassi | пе̄ссь [pʲi͜esʲː~pʲeːsʲː] |

пизэ [pize] |

пыжаш [pəʒaʃ] |

поз [poz] |

пуз [puz] |

fészek | пити [pitʲi] |

пить аня | (pit́ī) | – | pĕl | пидя [pʲidʲɐ] |

| 'hand, arm' | *käte | käsi (käte-) | käsi (käe-) | käsi (käe-) | gïete [kɨedə] |

giehta | кӣдт [kʲiːd̥ː] |

кедь [kedʲ] |

кид [kid] |

ки [ki] |

ки [ki] |

kéz | ка̄т [kaːt] |

кат, коат | (kät) | – | köt | – |

| 'eye' | *śilmä | silmä | silm (silma-) | silm (silmä-) | tjelmie [t͡ʃɛlmie] |

čalbmi | чалльм [t͡ʃalʲːm] |

сельме [sʲelʲme] |

шинча [ʃint͡ɕa] |

син (синм-) [ɕin] ([ɕinm-] |

син (синм-) [ɕin] ([ɕinm-] |

szem | сам [sam] |

сам | (šøm) | сєм | sem | сэв [sæw(ə̥)] |

| 'fathom' | *süle | syli (syle-) | süli (süle-) | – | sïlle [sʲɨllə] |

salla | сэ̄лл [sɛːlː] |

сэль [selʲ] |

шӱлӧ [ʃylø] |

сыв (сыл-) [sɯʋ] ([sɯl-] |

сул [sul] |

öl(el) | тал [tal] |

тал | (täl) | ԓăԓ | lö̆l | тибя [tʲibʲɐ] |

| 'vein / sinew' | *sëne | suoni (suone-) | soon (soone-) | suuń (soonõ-) | soene [suonə] |

suotna | сӯнн [suːnː] |

сан [san] |

шӱн [ʃyn] |

сӧн [sɘn] |

сӧн [sɘn] |

ín | та̄н [taːn] |

тан | (tɛ̮̄n)/(tǟn) | ԓон | lan | тэʼ [tɤʔ] |

| 'bone' | *luwe | luu | luu | luu | – | – | – | ловажа [lovaʒa] |

лу [lu] |

лы [lɯ] |

лы [lɯ] |

– | лув [luβ] |

ласм (?) | (täuˈt) | ԓўв | lŏγ | лы [lɨ] |

| 'blood' | *were | veri | veri | veri | vïrre [vʲɨrrə] |

varra | вэ̄рр [vɛːrː] |

верь [verʲ] |

вӱр [βyr] |

вир [ʋir] |

вир [ʋir] |

vér | - | выр (?) | (ūr) | вўр | wər | – |

| 'liver' | *mëksa | maksa | maks (maksa-) | mass (massa-) | mueksie [mʉeksie] |

– | – | максо [makso] |

мокш [mokʃ] |

мус (муск-) [mus] ([musk-] |

мус (муск-) [mus] ([musk-] |

máj | ма̄йт [maːjt] |

мяйт | (majət) | мухәԓ | muγəl | мыд [mɨd(ə̥)] |

| 'urine' / 'to urinate' |

*kuńśe | kusi (kuse-) | kusi (kuse-) | kusi (kusõ-) | gadtjedh (gadtje-) [kɑdd͡ʒə]- |

gožžat (gožža-) |

коннч [koɲːt͡ʃ] |

– | кыж [kəʒ] |

кудз [kud͡ʑ] |

кызь [kɯʑ] |

húgy | хуньсь [xunʲɕ] |

хос-вить | (kho̰ś-üt́) | (xŏs-) | kŏs- | – |

| 'to go' | *mene- | mennä (men-) | minema (min-) | minemä (min-) | mïnnedh [mʲɨnnə]- |

mannat | мэ̄ннэ [mɛːnːɛ] |

– | мияш (мий-) [mijaʃ] ([mij-]) |

мунны (мун-) [munnɯ] ([mun-]) |

мыныны (мын-) [mɯnɯnɯ] ([mɯn-]) |

menni | минуӈкве [minuŋkʷe] |

мыных | (mińo̰ŋ) | мăнты | mĕn- | минзь (мин-) [mʲinzʲ(ə̥)] ([mʲin-]) |

| 'to live' | *elä- | elää (elä-) | elama (ela-) | elämä (elä-) | jieledh [jielə] |

eallit | е̄лле [ji͜elʲːe~jeːlʲːe] | – | илаш (ила-) [ilaʃ] ([il-]) |

овны (ол-) [oʋnɯ] ([ol-]) |

улыны (ул-) [ulɯnɯ] ([ul-]) |

élni | ялтуӈкве [jaltuŋkʷe] |

ялтых | (ilto̰ŋ) | – | – | илесь (иль-) [jilʲesʲ(ə̥)] ([jilʲ-]) |

| 'to die' | *kale- | kuolla (kuol-) | koolma (kool-) | kuulma (kool-) | – | – | – | куломс (кул-) [kuloms] ([kul-]) |

колаш (кол-) [kolaʃ] ([kol-]) |

кувны (кул-) [kuʋnɯ] ([kul-]) |

кулыны (кул-) [kulɯnɯ] ([kul-]) |

halni | - | - | (khåləŋ) | хăԓты | kăla- | хась (ха-) [hʌsʲ(ə̥)] ([hʌ-]) |

| 'to wash' | *mośke- | – | – | mõskma (mõsk-) | – | – | – | муськемс (муськ-) [musʲkems] ([musʲk-]) |

мушкаш (мушк-) [muʃkaʃ] ([muʃk-]) |

мыськыны (мыськ-) [mɯɕkɯnɯ] ([mɯɕk-]) |

миськыны (миськ-) [miɕkɯnɯ] ([miɕk-]) |

mosni | – | - | - | – | – | масась (мас-) [mʌsəsʲ(ə̥)] ([mʌs-]) |

Orthographical notes: The hacek denotes postalveolar articulation (⟨ž⟩ [ʒ], ⟨š⟩ [ʃ], ⟨č⟩ [t͡ʃ]) (In Northern Sámi, (⟨ž⟩ [dʒ]), while the acute denotes a secondary palatal articulation (⟨ś⟩ [sʲ ~ ɕ], ⟨ć⟩ [tsʲ ~ tɕ], ⟨l⟩ [lʲ]) or, in Hungarian, vowel length. The Finnish letter ⟨y⟩ and the letter ⟨ü⟩ in other languages represent the high rounded vowel [y]; the letters ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ö⟩ are the front vowels [æ] and [ø].

As is apparent from the list, Finnish is the most conservative of the Uralic languages presented here, with nearly half the words on the list above identical to their Proto-Uralic reconstructions and most of the remainder only having minor changes, such as the conflation of *ś into /s/, or widespread changes such as the loss of *x and alteration of *ï. Finnish has also preserved old Indo-European borrowings relatively unchanged. (An example is porsas ("pig"), loaned from Proto-Indo-European *porḱos or pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian *porśos, unchanged since loaning save for loss of palatalization, *ś > s.)

Mutual intelligibility

[edit]The Estonian philologist Mall Hellam proposed cognate sentences that she asserted to be mutually intelligible among the three most widely spoken Uralic languages: Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian:[69]

- Estonian: Elav kala ujub vee all.

- Finnish: Elävä kala ui veden alla.

- Hungarian: (Egy) élő hal úszik a víz alatt.

- English: A living fish swims underwater.

However, linguist Geoffrey Pullum reports that neither Finns nor Hungarians could understand the other language's version of the sentence.[70]

Comparison

[edit]This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Unusable on mobile site. (April 2024) |

No Uralic language has exactly the idealized typological profile of the family. Typological features with varying presence among the modern Uralic language groups include:[71]

| Feature | Samoyedic | Ob-Ugric | Hungarian | Permic | Mari | Mordvin | Finnic | Sámi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Consonant length | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Consonant gradation | −1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Vowel harmony | −2 | −2 | + | − | + | + | +3 | − |

| Grammatical vowel alternation (ablaut or umlaut) |

+ | + | − | − | − | − | −4 | + |

| Dual number | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Distinction between inner and outer local cases |

− | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Determinative inflection (verbal marking of definiteness) |

+ | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Passive voice | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Negative verb | + | − | − | + | + | ± | + | + |

| SVO word order | − | − | − | ±5 | − | + | + | + |

Notes:

- Clearly present only in Nganasan.

- Vowel harmony is present in the Uralic languages of Siberia only in some marginal archaic varieties: Nganasan, Southern Mansi and Eastern Khanty.

- Only recently lost in modern Estonian

- A number of umlaut processes are found in Livonian.

- In Komi, but not in Udmurt.

Proposed relations with other language families

[edit]Many relationships between Uralic and other language families have been suggested, but none of these is generally accepted by linguists at the present time: All of the following hypotheses are minority views at the present time in Uralic studies.

Uralic-Yukaghir

[edit]The Uralic–Yukaghir hypothesis identifies Uralic and Yukaghir as independent members of a single language family. It is currently widely accepted that the similarities between Uralic and Yukaghir languages are due to ancient contacts.[72] Regardless, the hypothesis is accepted by a few linguists and viewed as attractive by a somewhat larger number.

Eskimo-Uralic

[edit]The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis associates Uralic with the Eskimo–Aleut languages. This is an old thesis whose antecedents go back to the 18th century. An important restatement of it was made by Bergsland (1959).[73]

Uralo-Siberian

[edit]Uralo-Siberian is an expanded form of the Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis. It associates Uralic with Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, and Eskimo–Aleut. It was propounded by Michael Fortescue in 1998.[74] Michael Fortescue (2017) presented new evidence in favor for a connection between Uralic and other Paleo-Siberian languages.[75]

Ural-Altaic

[edit]Theories proposing a close relationship with the Altaic languages were formerly popular, based on similarities in vocabulary as well as in grammatical and phonological features, in particular the similarities in the Uralic and Altaic pronouns and the presence of agglutination in both sets of languages, as well as vowel harmony in some. For example, the word for "language" is similar in Estonian (keel) and Mongolian (хэл (hel)). These theories are now generally rejected[76] and most such similarities are attributed to language contact or coincidence.

Indo-Uralic

[edit]The Indo-Uralic (or "Indo-Euralic") hypothesis suggests that Uralic and Indo-European are related at a fairly close level or, in its stronger form, that they are more closely related than either is to any other language family.

Uralo-Dravidian

[edit]The hypothesis that the Dravidian languages display similarities with the Uralic language group, suggesting a prolonged period of contact in the past,[77] is popular amongst Dravidian linguists and has been supported by a number of scholars, including Robert Caldwell,[78] Thomas Burrow,[79] Kamil Zvelebil,[80] and Mikhail Andronov.[81] This hypothesis has, however, been rejected by some specialists in Uralic languages,[82] and has in recent times also been criticised by other Dravidian linguists, such as Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.[83] Stefan Georg[84] describes the theory as "outlandish" and "not meriting a second look" even in contrast to hypotheses such as Uralo-Yukaghir or Indo-Uralic.

Nostratic

[edit]Nostratic associates Uralic, Indo-European, Altaic, Dravidian, Afroasiatic, and various other language families of Asia. The Nostratic hypothesis was first propounded by Holger Pedersen in 1903[85] and subsequently revived by Vladislav Illich-Svitych and Aharon Dolgopolsky in the 1960s.

Eurasiatic

[edit]Eurasiatic resembles Nostratic in including Uralic, Indo-European, and Altaic, but differs from it in excluding the South Caucasian languages, Dravidian, and Afroasiatic and including Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Nivkh, Ainu, and Eskimo–Aleut. It was propounded by Joseph Greenberg in 2000–2002.[86][87] Similar ideas had earlier been expressed by Heinrich Koppelmann in 1933 and by Björn Collinder in 1965.[88][89]

Uralic skepticism

[edit]The linguist Angela Marcantonio has argued against the validity of several subgroups of the Uralic family, as well against the family itself, claiming that many of the languages are no more closely related to each other than they are to various other Eurasian languages (e.g. Yukaghir or Turkic), and that in particular Hungarian is a language isolate.[90]

Marcantonio's proposal has been strongly dismissed by most reviewers as unfounded and methodologically flawed.[91][92][93][94][95][96] Problems identified by reviewers include:

- Misrepresentation of the amount of comparative evidence behind the Uralic family, by arbitrarily ignoring data and mis-counting the number of examples known of various regular sound correspondences[91][93][94][95][96]

- After arguing against the proposal of a Ugric subgroup within Uralic, claiming that this would constitute evidence that Hungarian and the Ob-Ugric languages have no relationship at all[91][92][93][96]

- Excessive focus on criticizing the work of early pioneer studies on the Uralic family, while ignoring newer, more detailed work published in the 20th century[92][94][95][96]

- Criticizing the evidence for the Uralic family as unsystematic and statistically insignificant, yet freely proposing alternate relationships based on even scarcer and even less systematic evidence.[91][93][94][95][96]

Other comparisons

[edit]Various unorthodox comparisons have been advanced. These are considered at best spurious fringe-theories by specialists:

- Finno-Basque[97]

- Hungarian-Etruscan[98]

- Sino-Uralic languages

- Cal-Ugrian theory

- Dené-Finnish (Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené and Uralic)[99]

- Minoan-Uralic[100]

- Alternative theories of Hungarian language origins

Comparison

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (in English): All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Comparison of the text in prominent Uralic languages:[101][102]

- Finnish: Kaikki ihmiset syntyvät vapaina ja tasavertaisina arvoltaan ja oikeuksiltaan. Heille on annettu järki ja omatunto, ja heidän on toimittava toisiaan kohtaan veljeyden hengessä.

- Livvi: Kai rahvas roittahes vällinny da taza-arvozinnu omas arvos da oigevuksis. Jogahizele heis on annettu mieli da omatundo da heil vältämättäh pidäy olla keskenäh, kui vellil.

- Veps: Kaik mehed sünduba joudajin i kohtaižin, ühtejiččin ičeze arvokahudes i oiktusiš. Heile om anttud mel’ i huiktusentund i heile tariž kožuda toine toiženke kut vel’l’kundad.

- Estonian: Kõik inimesed sünnivad vabadena ja võrdsetena oma väärikuselt ja õigustelt. Neile on antud mõistus ja südametunnistus ja nende suhtumist üksteisesse peab kandma vendluse vaim.

- Livonian: Amād rovzt attõ sindõnd brīd ja īdlizt eņtš vǟrtitõks ja õigiztõks. Näntõn um andtõd mūoštõks ja sidāmtundimi, ja näntõn um īdtuoisõ tuoimõmõst veļkub vaimsõ.

- Northern Sami: Buot olbmot leat riegádan friddjan ja olmmošárvvu ja olmmošvuoigatvuođaid dáfus. Sii leat jierbmalaš olbmot geain lea oamedovdu ja sii gálggaše leat dego vieljačagat.

- Erzya: Весе ломантне чачить олякс ды правасост весе вейкетекс. Сынст улить превест-чарьксчист ды визькстэ чарькодемаст, вейке-вейкень коряс прясь тенст ветяма братонь ёжо марто., romanized: Veśe lomańt́ńe čačit́ oĺaks di pravasost veśe vejket́eks. Sinst uĺit́ pŕevest-čaŕksčist di viźkste čaŕkod́emast, vejke-vejkeń koŕas pŕaś t́eńst vet́ama bratoń jožo marto.

- Komi-Permyak: Быдӧс отирыс чужӧны вольнӧйезӧн да ӧткоддезӧн достоинствоын да правоэзын. Нылӧ сетӧм мывкыд да совесть овны ӧтамӧдныскӧт кыдз воннэзлӧ., romanized: Bydös oťirys ćužöny voľnöjjezön da ötkoďďezön dostoinstvoyn da pravoezyn. Nylö śetöm myvkyd da sovesť ovny ötamödnysköt kydź vonnezlö.

- Nenets: Ет хибяри ненэць соямарианта хуркари правада тнява, ӈобой ненэця ниду нись токалба, ӈыбтамба илевату тара., romanized: Jet° x́ibaŕi ńeneć° sojamaŕianta xurkaŕi pravada tńawa, ŋoboj° ńeneća ńidu ńiś° tokalba, ŋibtamba iľewatu tara., lit. 'Each person is born with all the rights, one person to another one should relate similarly.'

- Hungarian: Minden emberi lény szabadon születik és egyenlő méltósága és joga van. Az emberek, ésszel és lelkiismerettel bírván, egymással szemben testvéri szellemben kell hogy viseltessenek.

Comparison of the text in other Uralic languages:[103][104]

- Northern Mansi: Ма̄ янытыл о̄лнэ мир пуссын аквхольт самын патэ̄гыт, аквтēм вос о̄лэ̄гыт, аквтēм нё̄тмил вос кинсэ̄гыт. Та̄н пуӈк о̄ньщēгыт, номсуӈкве вēрмēгыт, э̄сырма о̄ньщэ̄гыт, халанылт ягпыгыӈыщ-яга̄гиӈыщ вос о̄лэ̄гыт., romanized: Mā ânytyl ōlnè mir pussyn akvholʹt samyn patè̄gyt, akvtēm vos ōlè̄gyt, akvtēm në̄tmil vos kinsè̄gyt. Tān puňk ōnʹsēgyt, nomsuňkve vērmēgyt, è̄syrma ōnʹsʹè̄gyt, halanylt âgpygyňysʹ-âgāgiňysʹ vos ōlè̄gyt.

- Northern Khanty: Хуԯыева мирӑт вәԯьня па имуртӑн вәԯты щира сєма питԯӑт. Ԯыв нумсаңӑт па ԯывеԯа еԯєм атум ут вєрты па кўтэԯн ԯыв ԯәхсӑңа вәԯԯӑт., romanized: Xułyewa mirăt wəł’nâ pa imurtăn wəłty ŝira sêma pitłăt. Ływ numsan̦ăt pa ływeła ełêm atum ut wêrty pa kŭtèłn ływ łəxsăn̦a wəłłăt.

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Rantanen, Timo; Tolvanen, Harri; Roose, Meeli; Ylikoski, Jussi; Vesakoski, Outi (2022-06-08). "Best practices for spatial language data harmonization, sharing and map creation—A case study of Uralic". PLOS ONE. 17 (6): e0269648. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1769648R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0269648. PMC 9176854. PMID 35675367.

- ^ Rantanen, Timo; Vesakoski, Outi; Ylikoski, Jussi; Tolvanen, Harri (2021-05-25), Geographical database of the Uralic languages, doi:10.5281/ZENODO.4784188

- ^ "Uralic". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Klaproth, Julius (1823). Asia Polyglotta (in German). Paris: A. Schubart. p. 182. hdl:2027/ia.ark:/13960/t2m66bs0q.

- ^ Stipa, Günter Johannes (1990). Finnisch-ugrische Sprachforschung von der Renaissance bis zum Neupositivismus (PDF). Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia (in German). Vol. 206. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. p. 294.

- ^ Bakró-Nagy, Marianne (2012). "The Uralic Languages". Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire. 90 (3): 1001–1027. doi:10.3406/rbph.2012.8272.

- ^ Tommola, Hannu (2010). "Finnish among the Finno-Ugrian languages". Mood in the Languages of Europe. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 155. ISBN 978-90-272-0587-2.

- ^ a b Aikio 2022, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Dziebel, German (1 October 2012). "On the homeland of the Uralic language family" (blog). Retrieved 21 March 2019 – via anthropogenesis.kinshipstudies.org.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1990). "The peoples of the Russian forest belt". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 231.

- ^ Hajdú, Péter (1975). Finno-Ugrian Languages and Peoples. London, UK: Deutsch. pp. 62–69. ISBN 978-0-233-96552-9 – via archive.org.

- ^ a b c Janhunen, Juha (2009). "Proto-Uralic—what, where and when?" (PDF). In Jussi Ylikoski (ed.). The Quasquicentennial of the Finno-Ugrian Society. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia 258. Helsinki: Société Finno-Ougrienne. ISBN 978-952-5667-11-0. ISSN 0355-0230.

- ^ Grünthal, Riho; Heyd, Volker; Holopainen, Sampsa; Janhunen, Juha A.; Khanina, Olesya; Miestamo, Matti; et al. (29 August 2022). "Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread". Diachronica. 39 (4): 490–524. doi:10.1075/dia.20038.gru. ISSN 0176-4225.

- ^ Török, Tibor (July 2023). "Integrating linguistic, archaeological and genetic perspectives unfold the origin of Ugrians". Genes. 14 (7): 1345. doi:10.3390/genes14071345. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 10379071. PMID 37510249.

- ^ Anderson, J.G.C., ed. (1938). Germania. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Sebeok, Thomas A. (15 August 2002). Portrait Of Linguists. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4411-5874-1. OCLC 956101732.

- ^ Korhonen 1986, p. 29.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 793–794.

- ^ a b Collinder, Björn (1965). An Introduction to the Uralic languages. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 8–27, 34.

- ^ Korhonen 1986, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 795–796.

- ^ Ruhlen, Merritt (1987). A Guide to the World's Languages. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 64–71. OCLC 923421379.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 796–798.

- ^ Wickman 1988, p. 798.

- ^ Korhonen 1986, p. 32.

- ^ Korhonen 1986, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 801–803.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 803–804.

- ^ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23 (1): 14–34.

- ^ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése II" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23 (3): 260–278.

- ^ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése III" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23 (4): 436–447.

- ^ Halász, Ignácz (1894). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése IV" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 24 (4): 443–469.

- ^ Szabó, László (1969). "Die Erforschung der Verhältnisses Finnougrisch–Samojedisch". Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher (in German). 41: 317–322.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 799–800.

- ^ Korhonen 1986, p. 49.

- ^ Wickman 1988, pp. 810–811.

- ^ "Lexica Societatis Fenno-Ugricae XXXV". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura (in Hungarian).

- ^ Russian figures from the 2010 census. Others from EU 2012 figures or others of comparable date.

- ^ a b Salminen, Tapani (2007). "Europe and North Asia". In Christopher Moseley (ed.). Encyclopedia of the world's endangered languages. London: Routlegde. pp. 211–280. ISBN 9780700711970.

- ^ Salminen, Tapani (2015). "Uralic (Finno-Ugrian) languages". Archived from the original on 10 January 2019.

- ^ Helimski, Eugene (2006). "The «Northwestern» group of Finno-Ugric languages and its heritage in the place names and substratum vocabulary of the Russian North" (PDF). In Nuorluoto, Juhani (ed.). The Slavicization of the Russian North (Slavica Helsingiensia 27). Helsinki: Department of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures. pp. 109–127. ISBN 978-952-10-2852-6.

- ^ a b Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Publications of the Philological Society. Vol. 35. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 55–68. ISBN 978-0-631-23170-7. OCLC 803186861.

- ^ a b c Salminen, Tapani (2002). "Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies".

- ^ Donner, Otto (1879). Die gegenseitige Verwandtschaft der Finnisch-ugrischen sprachen (in German). Helsinki. OCLC 1014980747.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Szinnyei, Josef (1910). Finnisch-ugrische Sprachwissenschaft (in German). Leipzig: G. J. Göschen'sche Verlagshandlung. pp. 9–21.

- ^ Itkonen, T. I. (1921). Suomensukuiset kansat (in Finnish). Helsinki: Tietosanakirjaosakeyhtiö. pp. 7–12.

- ^ Setälä, E. N. (1926). "Kielisukulaisuus ja rotu". Suomen suku (in Finnish). Helsinki: Otava.

- ^ Hájdu, Péter (1962). Finnugor népek és nyelvek (in Hungarian). Budapest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hajdu, Peter (1975). Finno-Ugric Languages and Peoples. Translated by G. F. Cushing. London: André Deutch Ltd.. English translation of Hajdú (1962).

- ^ Itkonen, Erkki (1966). Suomalais-ugrilaisen kielen- ja historiantutkimuksen alalta. Tietolipas (in Finnish). Vol. 20. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura. pp. 5–8.

- ^ Austerlitz, Robert (1968). "L'ouralien". In Martinet, André (ed.). Le langage.

- ^ Voegelin, C. F.; Voegelin, F. M. (1977). Classification and Index of the World's Languages. New York/Oxford/Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 341–343. ISBN 9780444001559.

- ^ Kulonen, Ulla-Maija (2002). "Kielitiede ja suomen väestön juuret". In Grünthal, Riho (ed.). Ennen, muinoin. Miten menneisyyttämme tutkitaan. Tietolipas. Vol. 180. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. pp. 104–108. ISBN 978-951-746-332-4.

- ^ a b Michalove, Peter A. (2002) The Classification of the Uralic Languages: Lexical Evidence from Finno-Ugric. In: Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, vol. 57

- ^ Häkkinen, Jaakko 2007: Kantauralin murteutuminen vokaalivastaavuuksien valossa. Pro gradu -työ, Helsingin yliopiston Suomalais-ugrilainen laitos. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe20071746

- ^ Lehtinen, Tapani (2007). Kielen vuosituhannet. Tietolipas. Vol. 215. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-951-746-896-1.

- ^ Häkkinen, Kaisa 1984: Wäre es schon an der Zeit, den Stammbaum zu fällen? – Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, Neue Folge 4.

- ^ a b Häkkinen, Jaakko 2009: Kantauralin ajoitus ja paikannus: perustelut puntarissa. – Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja 92.

- ^ Bartens, Raija (1999). Mordvalaiskielten rakenne ja kehitys (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. p. 13. ISBN 978-952-5150-22-3.

- ^ Viitso, Tiit-Rein. Keelesugulus ja soome-ugri keelepuu. Akadeemia 9/5 (1997)

- ^ Viitso, Tiit-Rein. Finnic Affinity. Congressus Nonus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum I: Orationes plenariae & Orationes publicae. (2000)

- ^ Sammallahti, Pekka (1988). "Historical phonology of the Uralic Languages". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Foreign Influences. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 478–554. ISBN 978-90-04-07741-6. OCLC 466103653.

- ^ Helimski, Eugene (1995). "Proto-Uralic gradation: Continuation and traces" (PDF). Congressus Octavus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum. Jyväskylä. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ^ Honkola, T.; Vesakoski, O.; Korhonen, K.; Lehtinen, J.; Syrjänen, K.; Wahlberg, N. (2013). "Cultural and climatic changes shape the evolutionary history of the Uralic languages". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26 (6): 1244–1253. doi:10.1111/jeb.12107. PMID 23675756.

- ^ "Livonian pronouns". Virtual Livonia. 8 February 2020.

- ^ Austerlitz, Robert (1990). "Uralic Languages" (pp. 567–576) in Comrie, Bernard, editor. The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press, Oxford (p. 573).

- ^ "Estonian Language" (PDF). Estonian Institute. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ^ Türk, Helen (2010). "Kihnu murraku vokaalidest". University of Tartu.

- ^ "The Finno-Ugrics: The dying fish swims in water", The Economist, pp. 73–74, December 24, 2005 – January 6, 2006, retrieved 2013-01-19

- ^ Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2005-12-26), "The Udmurtian code: saving Finno-Ugric in Russia", Language Log, retrieved 2009-12-21

- ^ Hájdu, Péter (1975). "Arealógia és urálisztika" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 77: 147–152. ISSN 0029-6791.

- ^ Rédei, Károly (1999). "Zu den uralisch-jukagirischen Sprachkontakten". Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen. 55: 1–58.

- ^ Bergsland, Knut (1959). "The Eskimo-Uralic hypothesis". Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 61: 1–29.

- ^ Fortescue, Michael D (1998). Language Relations Across Bering Strait: Reappraising the Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence. Open linguistics series. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-70330-2. OCLC 237319639.

- ^ "Correlating Palaeo-Siberian languages and populations: Recent advances in the Uralo-Siberian hypothesis" (PDF). ResearchGate. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Georg, Stefan; Michalove, Peter A.; Ramer, Alexis Manaster; Sidwell, Paul J. (March 1999). "Telling general linguists about Altaic". Journal of Linguistics. 35 (1): 65–98. doi:10.1017/S0022226798007312. ISSN 1469-7742. S2CID 144613877.

- ^ Tyler, Stephen (1968). "Dravidian and Uralian: The lexical evidence". Language. 44 (4): 798–812. doi:10.2307/411899. JSTOR 411899.

- ^ Webb, Edward (1860). "Evidences of the Scythian Affinities of the Dravidian Languages, Condensed and Arranged from Rev. R. Caldwell's Comparative Dravidian Grammar". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 7: 271–298. doi:10.2307/592159. JSTOR 592159.

- ^ Burrow, T. (1944). "Dravidian Studies IV: The body in Dravidian and Uralian". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 328–356. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00072517. S2CID 246637174.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil (2006). "Dravidian Languages". Encyclopædia Britannica (DVD ed.).

- ^ Andronov, Mikhail S. (1971). Comparative studies on the nature of Dravidian-Uralian parallels: A peep into the prehistory of language families. Proceedings of the Second International Conference of Tamil Studies. Madras. pp. 267–277.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil (1970). Comparative Dravidian Phonology. The Hauge: Mouton. p. 22.

bibliography of articles supporting and opposing the hypothesis

- ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-521-77111-0.

- ^ Georg, Stefan (2023). "Connections between Uralic and other language families". In Abondolo, Daniel; Valijärvi, Riitta-Liisa (eds.). The Uralic languages. Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 176–209.

- ^ Pedersen, Holger (1903). "Türkische Lautgesetze" [Turkish Phonetic Laws]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 57 (3): 535–561. ISSN 0341-0137. OCLC 5919317968.

- ^ Greenberg, Joseph Harold (2000). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family. Vol. 1: Grammar. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3812-5. OCLC 491123067.

- ^ Greenberg, Joseph H. (2002). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family. Vol. 2: Lexicon. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4624-3. OCLC 895918332.

- ^ Koppelmann, Heinrich L. (1933). Die Eurasische Sprachfamilie: Indogermanisch, Koreanisch und Verwandtes (in German). Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- ^ Collinder, Björn (1965). An Introduction to the Uralic Languages. University of California Press. pp. 30–34.

- ^ Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Publications of the Philological Society. Vol. 35. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23170-7. OCLC 803186861.

- ^ a b c d Aikio, Ante (2003). "Angela Marcantonio, The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics". Book review. Word. 54 (3): 401–412. doi:10.1080/00437956.2003.11432539.

- ^ a b c Bakro-Nagy, Marianne (2005). "The Uralic Language Family. Facts, Myths and Statistics". Book review. Lingua. 115 (7): 1053–1062. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2004.01.008.

- ^ a b c d Georg, Stefan (2004). "Marcantonio, Angela: The Uralic Language Family. Facts, Myths and Statistics". Book review. Finnisch-Ugrische Mitteilungen. 26/27: 155–168.

- ^ a b c d Kallio, Petri (2004). "The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Angela Marcantonio". Book review. Anthropological Linguistics. 46: 486–490.

- ^ a b c d Kulonen, Ulla-Maija (2004). "Myyttejä uralistiikasta. Angela Marcantonio. The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics". Book review. Virittäjä (2/2004): 314–320.

- ^ a b c d e Laakso, Johanna (2004). "Sprachwissenschaftliche Spiegelfechterei (Angela Marcantonio: The Uralic language family. Facts, myths and statistics)". Book review. Finnisch-ugrische Forschungen (in German). 58: 296–307.

- ^ Trask, R.L. (1997). The History of Basque. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ^ Alinei, Mario (2003). Etrusco: Una forma arcaica di ungherese. Bologna, IT: Il Mulino.

- ^ "Uralic languages | Britannica". 10 April 2024.

- ^ Revesz, Peter (2017-01-01). "Establishing the West-Ugric language family with Minoan, Hattic and Hungarian by a decipherment of Linear A". WSEAS Transactions on Information Science and Applications.

- ^ "UN Human Rights". Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ^ "Article 1 of the UDHR in Uralic languages".

- ^ Помбандеева, Светлана (2014-09-17). "Мā янытыл о̄лнэ мир мāгыс хансым мāк потыр - Всеобщая декларация прав человека". Лӯима̄ сэ̄рипос (18).

- ^ Решетникова, Раиса (2014-09-17). "Хӑннєхә вәԯты щир оԯӑңӑн декларация нєпек - Всеобщая декларация прав человека". Хӑнты ясӑң (18).

Sources

[edit]- Abondolo, Daniel M., ed. (1998). The Uralic Languages. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08198-X.

- Aikio, Ante (24 March 2022). "Chapter 1: Proto-Uralic". In Bakró-Nagy, Marianne; Laakso, Johanna; Skribnik, Elena (eds.). The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198767664 – via academia.edu.

- Collinder, Björn, ed. (1977) [1955]. Fenno-Ugric Vocabulary: An etymological dictionary of the Uralic languages (rev. 2nd ed.). (1955) Stockholm, SV / (1977) Hamburg, DE: (1955) Almqvist & Viksell / (1977) Helmut Buske Verlag.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

- Collinder, Björn (1957). Survey of the Uralic Languages. Stockholm, SV.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Collinder, Björn (1960). Comparative Grammar of the Uralic Languages. Stockholm, SV: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Comrie, Bernhard (1988). "General features of the Uralic languages". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 451–477.

- Décsy, Gyula (1990). The Uralic Proto-Language: A comprehensive reconstruction. Bloomington, IN.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Hajdu, Péter (1963). Finnugor népek és nyelvek. Budapest, HU: Gondolat kiadó.

- Helimski, Eugene. 2000. Comparative Linguistics, Uralic Studies. Lectures and Articles. Moscow. (Russian: Хелимский Е.А. Компаративистика, уралистика. Лекции и статьи. М., 2000.)

- Laakso, Johanna (1992). Uralilaiset kansat [Uralic Peoples] (in Finnish). Porvoo – Helsinki – Juva. ISBN 951-0-16485-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Korhonen, Mikko (1986). Finno-Ugrian Language Studies in Finland 1828–1918. Helsinki, FI: Societas Scientiarum Fennica. ISBN 951-653-135-0.

- Napolskikh, Vladimir. 1991. The First Stages of Origin of People of Uralic Language Family: Material of mythological reconstruction. Moscow, RU (Russian: Напольских В. В. Древнейшие этапы происхождения народов уральской языковой семьи: данные мифологической реконструкции. М., 1991.)

- Rédei, Károly, ed. (1986–1988). Uralisches etymologisches Wörterbuch [Uralic Etymological Dictionary] (in German). Budapest, HU.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Wickman, Bo (1988). "The history of Uralic linguistics". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, history, and foreign influences. Leiden: Brill. pp. 792–818. ISBN 978-90-04-07741-6. OCLC 16580570 – via archive.org.

- External classification

- Sauvageot, Aurélien (1930). Recherches sur le vocabulaire des langues ouralo-altaïques [Research on the Vocabulary of the Uralo-Altaic Languages] (in French). Paris, FR.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Linguistic issues

- Künnap, A. (2000). Contact-Induced Perspectives in Uralic Linguistics. LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics. Vol. 39. München, DE: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-964-3.

- Wickman, Bo (1955). The Form of the Object in the Uralic Languages. Uppsala, SV: Lundequistska bokhandeln.

Further reading

[edit]- Preda-Balanica, Bianca Elena. "Contacts: Programme and Abstracts." University of Helsinki (2019).

- Bakró-Nagy, Marianne (2012). "The Uralic Languages". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire (in French). 90 (3): 1001–1027. doi:10.3406/rbph.2012.8272. ISSN 0035-0818.

- Kallio, Petri [in Norwegian Nynorsk] (2015-01-01). "The Language Contact Situation in Prehistoric Northeastern Europe". In Robert Mailhammer; Theo Vennemann gen. Nierfeld; Birgit Anette Olsen (eds.). The Linguistic Roots of Europe: Origin and Development of European Languages. Copenhagen Studies in Indo-European. Vol. 6. pp. 77–102.

- Holopainen, S. (2023). "The RUKI Rule in Indo-Iranian and the Early Contacts with Uralic". In Nikolaos Lavidas; Alexander Bergs; Elly van Gelderen; Ioanna Sitaridou (eds.). Internal and External Causes of Language Change: The Naxos Papers. Springer Nature. pp. 315–346. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-30976-2_11. ISBN 9783031309762.

External links

[edit]- "Early Indo-Iranic loans in Uralic: Sounds and strata" (PDF). Martin Joachim Kümmel, Seminar for Indo-European Studies.

- Syrjänen, Kaj, Lehtinen, Jyri, Vesakoski, Outi, de Heer, Mervi, Suutari, Toni, Dunn, Michael, … Leino, Unni-Päivä. (2018). lexibank/uralex: UraLex basic vocabulary dataset (Version v1.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1459402

KSF

KSF