Waptia

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 14 min

| Waptia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

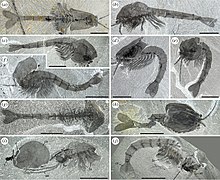

| Fossil specimens of Waptia | |

| |

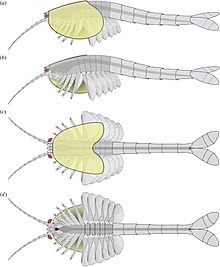

| Artist's reconstruction of Waptia fieldensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Mandibulata |

| Order: | †Hymenocarina |

| Genus: | †Waptia Walcott, 1912 |

| Species: | †W. fieldensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Waptia fieldensis Walcott, 1912

| |

| |

| Location of the Burgess Shale Formation in British Columbia | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Waptia is an extinct genus of marine arthropod from the Middle Cambrian of North America. It grew to a length of 6.65 cm (3 in), and had a large bivalved carapace and a segmented body terminating into a pair of tail flaps. It was an active swimmer and likely a predator of soft-bodied prey. It is also one of the oldest animals with direct evidence of brood care. Waptia fieldensis is the only species classified under the genus Waptia, and is known from the Burgess Shale Lagerstätte of British Columbia, Canada. Specimens of Waptia are also known from the Spence Shale of Utah, United States.

Based on the number of individuals, Waptia fieldensis is the third most abundant arthropod from the Burgess Shale Formation, with thousands of specimens collected. It was among the first fossils found by the American paleontologist Charles D. Walcott in 1909. He described it in 1912 and named it after two mountains near the discovery site – Wapta Mountain and Mount Field.

Although it bears a remarkable resemblance to modern crustaceans, its taxonomic affinities were long unclear. A comprehensive redescription published in 2018 classified it a member of Hymenocarina (which contains numerous other bivalved arthropods) within Mandibulata.

Description

[edit]

Known specimens of Waptia range in length from 13.5 to 66.5 millimetres (0.53 to 2.62 in) with the vast majority (~85%) being 40 to 60 millimetres (1.6 to 2.4 in) long. The bivalved carapace was saddle shaped, and was thin and non mineralised, and was likely flexible in life. The carapace was laterally compressed (narrow along the sideways axis), and had no distinct boundary between the two halves. The carapace was only attached to the body in a small section near the front of the head. The body was divided into three main segments, the cephalothorax (head), the post-cephalothorax, and the abdomen.[1]

The front of the head bore a pair of reniform (kidney shaped) compound eyes, about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) across, which were born on short stalks. One specimen with preserved ommatidia shows that density of ommatidia in the eye was about 600 per square millimetre. It is suggested that this allowed good forward and peripheral vision. A pair of small lobes, about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) long, protrude near the eyes. Similar structures are known from the related Canadaspis as well as other mandibulates, and are thought to correspond to the hemi-ellipsoid bodies of crustaceans, and thus likely have an olfactory function. Between the eyes is a triangular structure, dubbed the "median triangular projection", which is probably homologous to the ‘anterior sclerite’ of other Cambrian arthropods. The head bears a pair of antennae, which are composed of 10 elongate cylindrical segments/podomeres, which sequentially reduce in width towards the tip of the antenna. The front ends of each podomere bear setae (hair-like structures), which are orientated at an angle of 75° to 95° relative to the antennae axis.[1]

The mandibles have a three-segmented projection, which are covered with setae. The mandibles shows evidence of sclerotisation toward the edge where the two mandibles contacted, which have a toothed margin. The mandibles likely had a biting and grinding function. The maxillae are composed of at least six, probably nine podomeres, the end podomere bears a pair of claws, along with numerous setae. These likely assisted food manipulation alongside the mandibles. The cephalothorax has four additional pairs of uniramous (single branched) leg-like appendages (endopods), the first three of which are well segmented, with 5 segments, which are tipped with claws, with a 4 or 5 segmented basipod with well developed endites (structures present on the underside of the limb), particularly on the first pair, which project inward from the legs. The fourth leg differs in the fact that only the very end of the leg is segmented, with the rest being annulated, with the annulated regions being fringed by lamellae.[1]

The "post-cephalothorax" has 5 segments, associated with 6 somites with corresponding pairs of uniramous annulated appendages, which are fringed with lamellae. The following abdomen is approximately 60% of the total length, with 6 segments and no corresponding legs, which terminates in a forked tail fluke, in which each fluke is composed of three segments.[1]

-

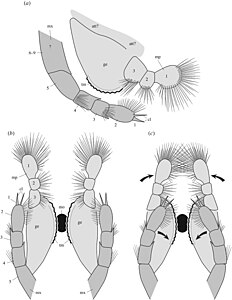

Diagram of the mandibles (light grey) and maxillae (dark grey) of Waptia in side-on (top) and from below (bottom) with the two versions showing movement range of the appendages.

-

Morphology of the cephalothoracic appendages in side-on view (top) and from the front

-

Post-cephalothorax appendages in side on view (a) with close-up of the tip of the appendage (b) and closeup of the lamellae (c), and a view from below of a sternite with attached appendages

Discovery

[edit]

Waptia fieldensis was one of the first fossils discovered by Charles D. Walcott from the Burgess Shale in August 1909. A rough sketch of Waptia is present in his diary for August 31, 1909, alongside sketches of Marrella and Naraoia.[3][4] A formal description for the species was published by Walcott in 1912. The species was named after the two mountains connected by the Fossil Ridge containing the Burgess Shale locality, Wapta Mountain and Mount Field of Yoho National Park, British Columbia, Canada.[5][6] The name of Wapta Mountain itself comes from the First Nation Nakoda word wapta, meaning "running water"; while Mount Field was named after the American telecommunications pioneer Cyrus West Field.[5]

Taphonomy

[edit]Specimens of Waptia fieldensis were recovered from the Burgess Shale Lagerstätte of Canada, which dates from the Middle Cambrian period (510 to 505 million years ago).[7] The locality was once about 200 m (660 ft) underwater; it was located at the bottom of a warm and shallow tropical sea adjacent to a submarine limestone cliff (now the Cathedral Limestone Formation). Undersea landslides caused by the collapse of parts of the limestone cliff would periodically bury the organisms in the area (as well as organisms carried by the landslides) in fine-grained mud that later became shale.[8]

Based on the number of individuals, Waptia fieldensis constitutes about 2.55% of the total number of organisms recovered from the Burgess Shale, and 0.86% of the Greater Phyllopod bed.[9] This makes them the third most abundant arthropods of the Burgess Shale (after Marrella and Canadaspis).[4][7] The National Museum of Natural History alone houses more than a thousand specimens of the species from the Burgess Shale.[10] Waptia fieldensis are often found disarticulated, with parts remaining in close proximity to each other.[9]

Specimens of Waptia, referred to as Waptia cf. fieldensis have also found recovered from the Middle Cambrian Spence Shale in Utah, USA.[5][11][12] Some of these specimens are associated with three dimensionally preserved eggs.[13]

Taxonomy

[edit]Waptia fieldensis is the only species accepted under the genus Waptia. It is classified under the family Waptiidae (established by Walcott in 1912).[10][14]

Some authors suggested that Waptia may be allied to crustaceans. Others proposed that it may be only distantly related to crustaceans, being at least a member of a stem group of crustaceans, or even of all arthropods.[5] Waptia was comprehensively redescribed in 2018, and was placed as part of the clade Hymenocarina within Mandibulata, closely related to Crustacea, due to the clear presence of mandibles and maxillae.[1]

In 1975, an apparently very similar species was described from the Lower Cambrian (515 to 520 million years ago) Maotianshan Shale Lagerstätte of Chengjiang, China. It was originally placed within the "ostracod"-like genus Mononotella, as Mononotella ovata. In 1991, Hou Xian-guang and Jan Bergström reclassified it under the new genus Chuandianella when additional discoveries of more complete specimens made its resemblance to W. fieldensis more apparent. Like W. fieldensis, Chuandianella ovata had a bivalved carapace with a median ridge, a pair of caudal rami, a single pair of antennae, and stalked eyes. In 2004, Jun-Yuan Chen tentatively transferred it to the genus Waptia. However, C. ovata had eight abdominal somites in contrast to five in W. fieldensis. Its limbs were biramous and were undifferentiated, unlike those of W. fieldensis.[10] Other authors deemed these differences to be enough to separate it from Waptia to its own genus.[5][15] In 2022, Chuandianella was redescribed, and was shown to lack mandibles, thus it is probably not closely related to Waptia, despite its similar appearance.[16]

In 2002, a second similar species, Pauloterminus spinodorsalis, was recovered from the Lower Cambrian Sirius Passet Lagerstätte of the Buen Formation of northern Greenland. It was also identified as a possible waptiid. Like C. ovata it had biramous undifferentiated appendages, but it also had only five abdominal somites like W. fieldensis. However, the poor preservation of the P. spinodorsalis specimens, particularly of the appendages on the head, make it difficult to ascertain its taxonomic placement. This difficulty is further compounded by evidence that the fossils of P. spinodorsalis may in fact be moults (exuviae), and not of the actual animal.[10]

Phylogeny of Hymenocarina after Izquierdo-López and Caron (2024):[17]

Ecology

[edit]While historically considered deposit feeders,[18] feeding by sifting through the sea bottom for edible organic particles,[3] the 2018 re-examination considered Waptia to have been an actively swimming predator of soft-bodied prey items, using its first three pairs of cephalothorax leg-like appendages to capture and manipulate prey, while moving its lamellated appendages in a rhythmic motion to propel itself through the water. Up and down movement of the abdomen and the tail fan was likely used to move vertically within the water column. It may have used the claws on its cephalothoracic leg-like appendages to occasionally rest on surfaces.[1]

In 2015, egg clutches were identified in six specimens from the Burgess Shale. The clutch sizes were small, only containing up to 24 eggs, but each egg was relatively large, with an average diameter of 2 mm (0.079 in). They were attached along the inner surface of the bivalved carapace. Along with Kunmingella douvillei and Chuandianella from the Chengjiang biota (around 7 million years older than the Burgess Shale) which also had fossilized eggs preserved inside the carapace, they constitute the oldest direct evidence of brood care and of K-selection among animals. It indicates that they probably lived in an environment which required them to take special measures to ensure the survival of their young.[19][20][21][22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Vannier, Jean; Aria, Cédric; Taylor, Rod S.; Caron, Jean-Bernard (June 2018). "Waptia fieldensis Walcott, a mandibulate arthropod from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (6): 172206. Bibcode:2018RSOS....572206V. doi:10.1098/rsos.172206. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 6030330. PMID 30110460.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 10-166, Walcott, Charles D, (Charles Doolittle), 1850-1927, Charles D. Walcott Collection

- ^ a b Derek E. G. Briggs; Douglas H. Erwin & Frederick J. Collier (1994). The Fossils of the Burgess Shale. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 1-56098-364-7.

- ^ a b Stephen Jay Gould (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393027051.

- ^ a b c d e "Waptia fieldensis". Royal Ontario Museum. 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ Charles D. Walcott (1912). "Cambrian geology and paleontology II: Middle Cambrian Branchiopoda, Malacostraca, Trilobita, and Merostomata". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 57 (6): 453–456.

- ^ a b Simon Conway Morris (1986). "The community structure of the Middle Cambrian Phyllopod Bed (Burgess Shale)". Palaeontology. 29 (Part 3): 423–467.

- ^ James W. Hagadorn (2002). "Burgess Shale: Cambrian Explosion in Full Bloom". In David J. Bottjer; et al. (eds.). Exceptional Fossil Preservation: A Unique View on the Evolution of Marine Life. Columbia University Press. pp. 61–89. ISBN 978-0-231-10254-4.

- ^ a b Jean-Bernard Caron & Donald A. Jackson (2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–465. Bibcode:2006Palai..21..451C. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. S2CID 53646959.

- ^ a b c d Rod S. Taylor (2002). "A new bivalved arthropod from the Early Cambrian Sirius Passet fauna, North Greenland". Palaeontology. 45 (Part 1): 97–123. Bibcode:2002Palgy..45...97T. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00229.

- ^ "Waptia cf. fieldensis Walcott, 1912". Division of Invertebrate Paleontology, University of Kansas. October 4, 2007. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ Derek E. G. Briggs; Bruce S. Lieberman; Jonathan R. Hendricks; Susan L. Halgedahl & Richard D. Jarrard (2008). "Middle Cambrian Arthropods from Utah". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (2): 238–254. Bibcode:2008JPal...82..238B. doi:10.1666/06-086.1. S2CID 31568651.

- ^ Moon, Justin; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Gaines, Robert R. (January 2022). "Synchrotron imagery of phosphatized eggs in Waptia cf. W . fieldensis from the middle Cambrian (Miaolingian, Wuliuan) Spence Shale of Utah". Journal of Paleontology. 96 (1): 152–163. Bibcode:2022JPal...96..152M. doi:10.1017/jpa.2021.77. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 239239374.

- ^ Mikko Haaramo (October 4, 2007). "Crustaceomorpha – crustaceans and related arthropods". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ Hu-Qin Liu & De-Gan Shu (2004). "New information on Chuandianella from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Fauna, Yunnan, China" [澄江化石库中川滇虫属化石的新信息]. Journal of Northwest University (Natural Science Edition) (in Chinese). 34 (4): 453–456.

- ^ Zhai, Dayou; Williams, Mark; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Sansom, Robert S.; Mai, Huijuan; Zhou, Runqing; Hou, Xianguang (2022-02-22). "Chuandianella ovata: An early Cambrian stem euarthropod with feather-like appendages". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25 (1): 1–22. doi:10.26879/1172. ISSN 1094-8074. S2CID 247123967.

- ^ Izquierdo‐López, Alejandro; Caron, Jean‐Bernard (24 July 2024). Barrett, Spencer (ed.). "The Cambrian Odaraia alata and the colonization of nektonic suspension-feeding niches by early mandibulates". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 291 (2027): 20240622. doi:10.1098/rspb.2024.0622. ISSN 1471-2954.

- ^ Roy E. Plotnick; Stephen Q. Dornbos & Jun-Yuan Chen (2010). "Information landscapes and sensory ecology of the Cambrian Radiation". Paleobiology. 36 (2): 303–317. doi:10.1666/08062.1. S2CID 13074384.

- ^ Jean-Bernard Caron & Jean Vannier (2016). "Waptia and the diversification of brood care in early arthropods". Current Biology. 26 (1): 69–74. Bibcode:2016CBio...26...69C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.006. PMID 26711492.

- ^ Yanhong Duana; Jian Hana; Dongjing Fua; Xingliang Zhanga; Xiaoguang Yanga; Tsuyoshi Komiyac & Degan Shua (2014). "Reproductive strategy of the bradoriid arthropod Kunmingella douvillei from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte, South China". Gondwana Research. 25 (3): 983–990. Bibcode:2014GondR..25..983D. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.03.011.

- ^ Emily Chung (18 December 2015). "Burgess Shale fossil Waptia may be oldest mom ever found caring for eggs". CBC News. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Ou, Qiang; Vannier, Jean; Yang, Xianfeng; Chen, Ailin; Mai, Huijuan; Shu, Degan; Han, Jian; Fu, Dongjing; Wang, Rong; Mayer, Georg (May 2020). "Evolutionary trade-off in reproduction of Cambrian arthropods". Science Advances. 6 (18): eaaz3376. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.3376O. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz3376. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7190318. PMID 32426476.

External links

[edit]- "Waptia fieldensis". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- "Waptia fieldensis". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2012.

KSF

KSF