Waterloo, Iowa

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 29 min

Waterloo, Iowa | |

|---|---|

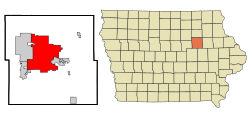

Location within Black Hawk County and Iowa | |

| Coordinates: 42°30′50″N 92°20′46″W / 42.51389°N 92.34611°W[1] | |

| Country | US |

| State | Iowa |

| County | Black Hawk |

| Incorporated | 1868 |

| Area | |

• City | 63.43 sq mi (164.29 km2) |

| • Land | 61.59 sq mi (159.53 km2) |

| • Water | 1.84 sq mi (4.76 km2) |

| Elevation | 883 ft (269 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 67,314 |

| • Rank | 8th in Iowa |

| • Density | 1,092.85/sq mi (421.95/km2) |

| • Metro | 169,895 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 50701-50707 |

| Area code | 319 |

| FIPS code | 19-82425 |

| GNIS ID | 468951[1] |

| Website | cityofwaterlooiowa |

Waterloo is a city in and the county seat of Black Hawk County, Iowa, United States.[3] It is the eighth-most populous city in Iowa, with a population of 67,314 at the 2020 census.[4] Waterloo comprises a twin conurbation with neighboring municipality Cedar Falls, and is the larger of the two cities. The Waterloo – Cedar Falls metropolitan area has an estimated 170,000 residents.

Waterloo is a major manufacturing, commercial, and cultural center in Northeast Iowa. Locally known as the "Factory City," John Deere brand agricultural machinery has been produced in the city for over a century.[5] Waterloo is bisected by the Cedar River flowing southeastward.

History

[edit]

Waterloo was originally known as Prairie Rapids Crossing.[6] The town was established near two Meskwaki American tribal seasonal camps alongside the Cedar River. It was first settled in 1845 when George and Mary Melrose Hanna and their children arrived on the east bank of the Red Cedar River (now just called the Cedar River). They were followed by the Virden and Mullan families in 1846. Evidence of these earliest families can still be found in the street names Hanna Boulevard, Mullan Avenue and Virden Creek.

On December 8, 1845, the Iowa State Register and Waterloo Herald was the first newspaper published in Waterloo.[7]

The name Waterloo supplanted the original name, Prairie Rapids Crossing, shortly after Charles Mullan petitioned for a post office in the town. Since the signed petition did not include the name of the proposed post office location, Mullan was charged with selecting the name when he submitted the petition. Tradition has it that as he flipped through a list of other post offices in the United States, he came upon the name Waterloo. The name struck his fancy, and a post office was established under that name. There were two extended periods of rapid growth over the next 115 years. From 1895 to 1915, the population increased from 8,490 to 33,097, a 290% increase. From 1925 to 1960, population increased from 36,771 to 71,755. The 1895 to 1915 period was a time of rapid growth in manufacturing, rail transportation and wholesale operations. During this period the Waterloo Gasoline Traction Engine Company moved to Waterloo and, shortly after, the Rath Packing Company moved from Dubuque. Another major employer throughout the first two-thirds of the 20th century was the Illinois Central Railroad. Among the others was the less-successful brass era automobile manufacturer, the Maytag-Mason Motor Company.[8]

On June 7, 1934, bank robber Tommy Carroll had a shootout with the FBI when he and his wife stopped to pick up gas. Accidentally parking next to a police car and wasting time dropping his gun and picking it back up, Carroll was forced to flee into an alley, where he was shot. He was taken to Allen Memorial Hospital in Waterloo, where he soon died.

Waterloo suffered in the agricultural recession of the 1980s; its major employers at the time were heavily rooted in agriculture. John Deere, the area's largest employer, cut 10,000 jobs, and the Rath meatpacking plant closed altogether, losing 2,500 jobs. It is estimated that Waterloo lost 14% of its population during this time.[9] Today the city enjoys a broader industrial base, as city leaders have sought to diversify its industrial and commercial mix. Deere remains a strong presence in the city, but employs only roughly one-third the number of people it did at its peak.

African American community

[edit]In 1910, black railroad workers were brought in as strikebreakers to the Waterloo area.[10][11] Black workers were relegated to 20 square blocks in Waterloo, an area that remains the east side to this day.[10][11] In 1940, more black strikebreakers were brought in to work in the Rath meat plant.[12] In 1948, a black strikebreaker killed a white union member. Instead of a race riot, a strike ensued against the Rath Company. The National Guard was called in to end the 73-day strike.[12]

Civil rights

[edit]United Packinghouse Workers of America became the main union of the Rath Company, welcoming black workers,[13] but United Auto Workers Local 838 continued to refuse black members.[14] With the power of the union, Anna Mae Weems, Ada Treadwell, Charles Pearson and Jimmy Porter formed an anti-discrimination department at Rath by the 1950s. This department helped organize protests against local places that discriminated against blacks.[10]

Porter would go on to organize the first black radio station in Waterloo, KBBG, in 1978.[11][13] Weems became the head of the anti-discrimination department and local NAACP chapter.[10]

On May 31, 1966, Eddie Wallace Sallis was found dead in the local jail. The black community felt the death was suspicious, and protests were held. On June 4, Weems led a march on city hall to encourage investigation into his death.[11][13] The march led to the creation of the Waterloo Human Rights Commission, which lasted only a year due to lack of funding.[12]

On Sept. 7, 1967, a city report, "Waterloo's Unfinished Business", was released.[15] The report covered the ongoing problems in housing, education and employment faced by Waterloo's black community. It confirmed the housing bias faced by black residents, that many of the schools were generally 80% of one race, and that 80% of black residents held service jobs.[15] In a 2007 article, the Courier covered some changes in the 40 years since, finding that housing was now mostly divided by socioeconomic status, schools still violated the desegregation plan, and black unemployment was still double that of white residents.[15]

The Iowa Supreme Court outlawed school segregation in 1868.[12] A 1967 commission found most schools were still segregated and recommended immediate desegregation, which Mayor Lloyd Turner opposed.[13] In 1969, the Waterloo school board voted to allow open enrollment in all their schools to encourage integration. Many parents felt it was not enough.[13] Despite the efforts between 1967 and 1970, already-black schools in the area increased in their segregation.[13]

Protests and riots

[edit]By the 1960s, Rath was declining and jobs there were harder to come by. A federal government program trained 1,200 local youths with the promise of summer jobs, only to hire two as bricklayers.[10] Starting in the summer months of 1966,[16] Waterloo was subject to riots over race relations between the white community and the black community. Many white residents expressed confusion as to why riots were occurring in Waterloo,[13][16] while younger black residents felt they were being treated unfairly, as their conditions seemed worse than those of their white neighbors.[16] In 1967, the black population of Waterloo was equivalent to 8%, and according to the Courier, had a 4% unemployment rate.[16] Waterloo was segregated at the time, as 95% of its black population lived in "East" Waterloo.[16] While the white community felt East High was integrated with a 45% black student body, the black community pointed out that the elementary school in East Waterloo had only one white pupil.

Protests were mostly organized by black youths aged 16–25.[15][16] Protests became riots when the youth felt protesting wasn't effective.[16] Protests turned into riots in July 1968[16] and reached a critical mass by September, with buildings on East 4th street torched and vandalized.[15]

In August 1968, East High students Terri and Kathy Pearson gave the principal a list of grievances detailing how they felt the discrimination could be lessened. The principal refused to implement any of the requested changes.[13] Student protests and walkouts continued through September. Students were angry that no African American history course was being taught, and that interracial dating was discouraged by teachers and administrators.[13]

On September 13, 1968, during an East High School football game, police attempted to arrest a black youth.[11] He resisted arrest, drawing attention of students in the stands. Black students fought and argued with the police, and police responded by using clubs and mace.[13] The riot continued into the east side of Waterloo, with a subsequent fire that claimed a lumber mill and three homes. There was an attempt to set East High on fire as well.[13] The riot lasted until midnight and resulted in seven officers injured and thirteen youths jailed. The National Guard was called in the following day. The riots were called off and a solution was reached thanks to civil rights leader William G Parker.[13]

21st century

[edit]In 2003, Governor Tom Vilsack created a task force to close the racial achievement gap in Waterloo.[17] In 2009, a fair housing report, "Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice", compiled by Mullin & Lonergan Associates Inc., found Waterloo to be Iowa's most segregated city.[14] "Historical patterns of racial segregation persist in Waterloo. Of the 20 cities in Iowa with populations exceeding 25,000, Waterloo ranks as the most segregated".[14]

Many activists who participated in the original protests feel that Waterloo has remained the same.[11][15] In 2015, The Huffington Post listed Waterloo as the 10th worst city for black Americans.[18] The site noted that the city's black residents have a 24% unemployment rate compared to 3.9% for whites, giving Waterloo one of the highest black unemployment rates among Midwest cities.[11] Waterloo still has a higher percentage of blacks than most Iowa cities.[11]

In December 2012, Derrick Ambrose Jr. was shot by a police officer. Ambrose's family maintains he was unarmed, while the officer stated that he felt his life was in danger. A grand jury acquitted the officer. The shooting sparked outrage in the community.[11]

Flood of 2008

[edit]

June 2008 saw the worst flooding the Waterloo – Cedar Falls area had ever recorded; other major floods include the Great Flood of 1993. The flood control system constructed in the 1970s–90s largely functioned as designed.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 63.23 square miles (163.76 km2), of which 61.39 square miles (159.00 km2) is land and 1.84 square miles (4.77 km2) is water.[19]

The average elevation of Waterloo is 846 feet above sea level. The population density is 1101 people per square mile, considered low for an urban area.[20]

Climate

[edit]Waterloo has a humid continental climate zone (Köppen classification Dfa),[21] typical of the state of Iowa, and is part of USDA Plant Hardiness zone 5a.[22] The normal monthly mean temperature ranges from 18.5 °F (−7.5 °C) in January to 73.6 °F (23.1 °C) in July. On average, there are 22 nights annually with a low at or below 0 °F (−18 °C), 58 days annually with a high at or below freezing, and 16 days with a high at or above 90 °F (32 °C). As the mean first and last occurrence of freezing temperatures is October 1 and April 29, respectively, this allows for a growing season of 154 days. Temperature records range from −34 °F (−37 °C) on March 1, 1962, and January 16, 2009, up to 112 °F (44 °C) on July 13 and 14, 1936, during the Dust Bowl. The record cold daily maximum is −16 °F (−27 °C) on February 2, 1996, while conversely the record warm daily minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on July 31, 1917, and August 16, 1988.[23]

Normal annual precipitation equivalent is 34.60 inches (879 mm) spread over an average of 112 days, with heavier rainfall in spring and summer, but observed annual rainfall has ranged from 17.35 to 53.07 inches (441 to 1,348 mm) in 1910 and 1993, respectively. The wettest month on record is July 1999 with 12.82 inches (326 mm); on the 2nd of that month, 5.49 inches (139 mm) of rain fell, making for the heaviest rainfall in a single calendar day. The driest months are October 1952 and November 1954 with trace amounts in each month.[23]

Winter snowfall is moderate, and averages 35.3 inches (90 cm) per season, spread over an average of 27 days, and snow cover of 1 inch (2.5 cm) or more is seen on 67 days, mostly from December to March. Winter snowfall has ranged from 11.6 inches (29.5 cm) in 1967–68 to 68.5 inches (174.0 cm) in 1904–05. The most snow in a calendar day and month is 13.2 and 33.9 inches (33.5 and 86.1 cm) on January 3, 1971, and in December 2000, respectively.[23]

| Climate data for Waterloo Regional Airport (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1895–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

78 (26) |

87 (31) |

100 (38) |

108 (42) |

107 (42) |

112 (44) |

110 (43) |

102 (39) |

95 (35) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 47.5 (8.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

70.5 (21.4) |

82.7 (28.2) |

88.8 (31.6) |

93.3 (34.1) |

94.3 (34.6) |

91.7 (33.2) |

90.6 (32.6) |

82.9 (28.3) |

67.5 (19.7) |

51.5 (10.8) |

95.9 (35.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 28.2 (−2.1) |

32.6 (0.3) |

46.5 (8.1) |

60.9 (16.1) |

72.8 (22.7) |

82.2 (27.9) |

85.0 (29.4) |

82.9 (28.3) |

76.8 (24.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

47.1 (8.4) |

33.7 (0.9) |

59.3 (15.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 19.4 (−7.0) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

36.7 (2.6) |

49.4 (9.7) |

61.5 (16.4) |

71.5 (21.9) |

74.5 (23.6) |

71.9 (22.2) |

64.6 (18.1) |

51.6 (10.9) |

37.4 (3.0) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

49.0 (9.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 10.7 (−11.8) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

37.9 (3.3) |

50.2 (10.1) |

60.8 (16.0) |

64.0 (17.8) |

61.0 (16.1) |

52.4 (11.3) |

40.2 (4.6) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

17.0 (−8.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −16.0 (−26.7) |

−9.8 (−23.2) |

2.2 (−16.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

45.7 (7.6) |

51.2 (10.7) |

48.2 (9.0) |

34.7 (1.5) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

7.9 (−13.4) |

−7.3 (−21.8) |

−19.6 (−28.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −34 (−37) |

−31 (−35) |

−34 (−37) |

−4 (−20) |

22 (−6) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

33 (1) |

19 (−7) |

0 (−18) |

−17 (−27) |

−29 (−34) |

−34 (−37) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.10 (28) |

1.14 (29) |

1.98 (50) |

4.04 (103) |

4.61 (117) |

5.72 (145) |

4.34 (110) |

4.17 (106) |

3.14 (80) |

2.76 (70) |

1.85 (47) |

1.44 (37) |

36.29 (922) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.1 (26) |

9.3 (24) |

4.6 (12) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

3.1 (7.9) |

9.9 (25) |

39.1 (99) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.1 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 11.5 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 113.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.8 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 26.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.0 | 73.8 | 72.7 | 66.4 | 65.7 | 67.7 | 71.9 | 73.7 | 73.7 | 69.9 | 74.8 | 77.2 | 71.8 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 14.0 (−10.0) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

42.1 (5.6) |

52.9 (11.6) |

62.1 (16.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

45.0 (7.2) |

32.7 (0.4) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

42.0 (5.6) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961–1990)[23][24][25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 4,337 | — | |

| 1880 | 5,630 | 29.8% | |

| 1890 | 6,674 | 18.5% | |

| 1900 | 12,580 | 88.5% | |

| 1910 | 26,693 | 112.2% | |

| 1920 | 36,230 | 35.7% | |

| 1930 | 46,191 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 51,743 | 12.0% | |

| 1950 | 65,198 | 26.0% | |

| 1960 | 71,755 | 10.1% | |

| 1970 | 75,533 | 5.3% | |

| 1980 | 75,985 | 0.6% | |

| 1990 | 66,467 | −12.5% | |

| 2000 | 68,747 | 3.4% | |

| 2010 | 68,406 | −0.5% | |

| 2020 | 67,314 | −1.6% | |

| Iowa Data Center[4] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[26] | Pop 2010[27] | Pop 2020[28] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 55,419 | 51,254 | 44,321 | 80.61% | 74.93% | 65.84% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 9,468 | 10,488 | 12,031 | 13.77% | 15.33% | 17.87% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 132 | 145 | 145 | 0.19% | 0.21% | 0.22% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 581 | 710 | 2,016 | 0.85% | 1.04% | 2.99% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 29 | 171 | 707 | 0.04% | 0.25% | 1.05% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 136 | 94 | 223 | 0.20% | 0.14% | 0.33% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 1,176 | 1,717 | 3,078 | 1.71% | 2.51% | 4.57% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,806 | 3,827 | 4,793 | 2.63% | 5.59% | 7.12% |

| Total | 68,747 | 68,406 | 67,314 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the census of 2020,[29] the population was 67,314. The population density was 1,092.8 inhabitants per square mile (421.9/km2). There were 31,603 housing units at an average density of 513.1 units per square mile (198.1 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 72.4% White, 17.3% Black or African American, 2.5% Asian, 0.5% Pacific Islander, 0.3% Native American, and 3.3% from other races or two or more races. Ethnically, the population was 7.1% Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[30] of 2010, there were 68,406 people, 28,607 households, 17,233 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,114.3 inhabitants per square mile (430.2/km2). There were 30,723 housing units at an average density of 500.5 units per square mile (193.2 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 77.3% White, 15.5% African American, 0.3% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 2.6% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 5.6% of the population.

There were 28,607 households, of which 29.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.3% were married couples living together, 14.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.8% were non-families. 31.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.95.

The median age in the city was 35.9 years. 23.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.4% were from 25 to 44; 25.5% were from 45 to 64; and 14% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

Metropolitan area

[edit]The Waterloo-Cedar Falls Metropolitan Statistical Area consists of Black Hawk, Bremer, and Grundy counties. The area had a 2000 census population of 163,706 and a 2008 estimated population of 164,220.[31]

Waterloo is next to Cedar Falls, home to the University of Northern Iowa. Small suburbs include Evansdale, Hudson, Raymond, Elk Run Heights, Gilbertville, and Washburn.

The largest employers in the Waterloo/Cedar Falls MSA, according to the Cedar Valley Regional Partnership of Iowa, as of 2021 include (in order): John Deere, Tyson Fresh Meats,[32] the University of Northern Iowa, Omega Cabinetry, Bertch Cabinet, Target Regional Distribution Center, Croell Redi Mix, Cuna Mutrual, and CBE Companies.[33]

Arts and culture

[edit]The Cedar Valley Arboretum & Botanic Gardens is a 40-acre (16 ha) public garden located directly east of Hawkeye Community College. Admission is $5/adult and $2/child, under five and members are free.[34]

The tropically themed Lost Island Waterpark, which opened in 2001, has regularly been featured in USA Today's Top 10 waterparks in the United States listings.[35] It was joined in 2022 by Lost Island Theme Park, which received industry awards recognition for its interactive dark ride Volkanu: Quest for the Golden Idol.[36]

The Iowa Irish Fest [37] is held in Waterloo in early August, and the National Cattle Congress is held there in September.

Silos & Smokestacks National Heritage Area

[edit]Silos & Smokestacks National Heritage Area (SSNHA) preserves and tells the story of American agriculture and its global significance through partnerships and activities that celebrate the land, people, and communities of the area. SSNHA is one of 62 federally designated National Heritage Areas and is an Affiliated Area of the National Park Service. Through the development of a network of 113 partner sites, programs and events, SSNHA's mission is to interpret farm life, agribusiness and rural communities-past and present. Waterloo partner sites include the Waterloo Center for the Arts and the Grout Museum. The SSNHA office is located in the Fowler Building, Suite 2, 604 Lafayette Street.[38]

Waterloo Center for the Arts

[edit]The Waterloo Center for the Arts (WCA) is a regional center for visual and performance arts. It is owned and operated by the City of Waterloo with oversight by the advisory Waterloo Cultural and Arts Commission. The center is located at 225 Commercial Street. It is also an anchor for the Waterloo Cultural and Arts District (a State of Iowa designation).[39]

The permanent collection at the WCA includes the largest collection of Haitian art in the country, Midwest Regionalist art (including works by Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton), Mexican folk art, international folk art, American decorative arts, and public art.[39]

President Barack Obama gave a speech here on August 14, 2012, during the 2012 presidential campaign. Originally scheduled for 7:45 pm, the speech was delayed by about 15 minutes, when Obama made an unannounced stop in neighboring Cedar Falls for a beer at a pub.[40][41][42]

Included in the WCA is the Phelps Youth Pavilion (PYP), which opened in 2009. The PYP is an interactive children's museum. PYP provides additional gallery and studio space.[39]

The Riverloop Amphitheater, completed in 2011, is an outdoor plaza and amphitheater available to rent for events and weddings. The Riverloop Amphitheater also is home to Mark's Park, a water park playground open to the public.[39]

The WCA also houses the Waterloo Community Playhouse, the oldest community theatre in Iowa (operating since 1916), and the Black Hawk Children's Theatre, that started in 1964, then, merged with the Waterloo Community Playhouse in 1982. Both perform in the Hope Martin Theatre, which opened in 1965. The theatre's administrative offices are located across the street in the historic Walker Building.[43]

Grout Museum District

[edit]

Established in 1932, the district started with an endowment set up in the will of Henry W. Grout.[44] The district is a nonprofit educational entity that is active in engaging the students and all people from the surrounding communities. It is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums.[45]

The Grout Museum of History and Science, the first museum which would grow into the museum district, was displayed for many years in the building that was the local YMCA. The current building was completed and opened to the public as a not-for-profit museum in 1956.[45]

The Sullivan Brothers Iowa Veterans Museum was opened in November 2008 at a cost of $11 million, funded in part by a citizens' grassroots campaign.[45]

The Rensselaer Russell House is at 520 W. 3rd Street. Built in 1858, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Rensselaer and Caroline Russell built the house utilizing Italianate architecture in 1861 for $5,878.83.[45]

The Carl A. and Peggy J. Bluedorn Science Imaginarium opened in 1993 and provides both interactive exhibits and formal demonstrations in various fields of science.[45]

The Snowden House is a two-story brick Victorian era house listed on the National Register of Historic Places was built in 1875. The house was once used as the Waterloo Woman's Club.

Library

[edit]Waterloo has one central public library. Each year, thousands of community members visit the library, borrow materials, get help from librarians, and use our computers and Wi-Fi. A detailed look at library usage, services, and collections, can be found here.

The library is governed by a board of trustees board of trustees, nominated by the city mayor and confirmed by the city council.

The Waterloo Public Library is in a renovated Great Depression era building that served as a post office and federal building. The building was renovated in the late 1970s for use as a library. In 2021, the Waterloo Public Library celebrated 40 years at its Commercial Street location.

Two New Deal-funded murals by artist Edgar Britton are on display at the library. Exposition is an image of the National Cattle Congress, and Holiday is of a picnic.

In popular culture

[edit]The 2015 film Carol uses Waterloo in a major plot point.[46]

In the 2022 film The Whale, the missionary Thomas, played by actor Ty Simpkins, says he was from Waterloo, Iowa.

Sports

[edit]Waterloo hosted a National Basketball Association (NBA) franchise for the 1949–50 season, being one of the smaller cities to have had a major league franchise in a Big Four American sport. The Waterloo Hawks (who hold no relation to the Atlanta Hawks) were a founding member of the NBA (under that name), but folded after one season.[47]

Waterloo hosted the Waterloo Microbes and Waterloo Hawks teams of minor league baseball, with professional baseball play beginning in 1895.

Waterloo is home to the junior ice hockey team Waterloo Black Hawks of the United States Hockey League. They play out of Young Arena.

Waterloo is home to the summer collegiate baseball team Waterloo Bucks of the Northwoods League.[48] The team was formed in 1995 and plays their home games at Riverfront Stadium (Waterloo). Until 1993, the stadium hosted a succession of professional minor league baseball teams.

Waterloo is also home to the Iowa Woo, an arena football team of The Arena League. They play at The Hippodrome.

Government

[edit]

Waterloo is administered by the mayor and council system of government. One council member is elected from each of Waterloo's five wards, and two are elected at-large. The current mayor is Quentin Hart. He is the city's first black mayor.

The city holds elections to elect its mayor and city council every two years, in odd-numbered off-year elections. Mayoral elections are held every two years, meanwhile each city council seat is up for grabs every four years.

| Member | Seat | Entered office | Next election |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quentin Hart | Mayor | January 1, 2016 | 2025 |

| Rob Nichols | At-large | January 1, 2022 | 2025 |

| Steve Simon | At-large | January 1, 2024 | 2027 |

| John Chiles | Ward 1 | January 1, 2022 | 2025 |

| Dave Boesen | Ward 2 | January 1, 2020[b] | 2027 |

| Nia Wilder | Ward 3 | January 1, 2022 | 2025 |

| Belinda Creighton-Smith | Ward 4 | March 14, 2023 | 2027 |

| Ray Feuss | Ward 5 | December 17, 2018 | 2025 |

Education

[edit]Hawkeye Community College is located in Waterloo. Neighboring Cedar Falls is home to the University of Northern Iowa.

Almost all of the city is within the Waterloo Community School District.[49] The three public high schools in the city are Waterloo West High School, Waterloo East High School, and Expo High School. Additionally, a portion of the city is within the Cedar Falls Community School District.[50]

Waterloo's private high schools are Waterloo Christian School and Columbus Catholic High School, which is supported by the Catholic parishes of Waterloo and Cedar Falls. Waterloo Christian is a non-denominational college preparatory school located on the grounds of Walnut Ridge Baptist Church. The school's colors are green and yellow, and its mascot is the "Regent". Columbus' mascot is the "Sailor", a connection to the school's namesake Christopher Columbus, and its colors are green and white.

There is also a wide array of elementary and junior high schools in the area, with open enrollment available.

Media

[edit]Radio

[edit]- FM stations

- AM stations

Television

[edit]- 2 KGAN (CBS, Fox on DT2) – located in Cedar Rapids

- 7 KWWL (NBC, Heroes & Icons on DT2, MeTV on DT3) – located in Waterloo

- 9 KCRG-TV (ABC, MyNetworkTV on DT2, The CW on DT3) – located in Cedar Rapids

- 12 KIIN (PBS/Iowa PBS) – located in Iowa City

- 20 KWKB (TCT, This TV on DT5) – located in Iowa City

- 28 KFXA (Dabl) – located in Cedar Rapids

- 32 KRIN (PBS/Iowa PBS) – located in Waterloo

- 40 KFXB-TV (CTN) – located in Dubuque

- 48 KPXR-TV (Ion) – located in Cedar Rapids

- The Courier, daily newspaper

- The Cedar Valley What Not, weekly advertiser

Infrastructure

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

Transportation

[edit]Waterloo is located at the northern end of Interstate 380. U.S. Highways 20, 63, and 218 and Iowa Highway 21 also run through the metropolitan area. The Avenue of the Saints runs through Waterloo.

American Airlines provides non-stop air service to and from Chicago from the Waterloo Regional Airport as of April 3, 2012. As of October 27, 2014, American Airlines runs two flights to/from Chicago O'Hare (ORD). Departures to Chicago are early morning and mid/late afternoon. Arrivals are early/mid-afternoon and evening.

Waterloo is served by a metropolitan bus system (MET), which serves most areas of Cedar Falls and Waterloo. Most routes meet at the central bus station in downtown Waterloo. The system operates Monday through Saturday. During the week the earliest bus is at 5:45 am from downtown Waterloo, and the last bus arrives downtown at 6:40 pm. Service is limited on Saturdays.

Waterloo is served by one daily intercity bus arrival and departure to Chicago and Des Moines, provided by Burlington Trailways. New service to and from Mason City and Minneapolis/St. Paul provided by Jefferson Lines started in the fall of 2009, however was canceled in 2012.[51]

There are currently five taxi operators in Waterloo and Cedar Falls: First Call, Yellow, City Cab, Cedar Valley Cab, and Dolly's Taxi.

The Chicago Central railroad runs through Waterloo.

Utilities

[edit]The MidAmerican Energy Company supplies Waterloo with electricity and natural gas. The Waterloo Water Works supplies potable water with a capacity of 50,400,000 GPD (gallons per day) with an average use of 13,400,000 GPD and a peak use of 28,800,000 GPD. News reports indicate that 18.5% of the system's output in 2013, or 851 million gallons, was unaccounted for.[52] Sanitation service (sewage) is operated by the city of Waterloo, with a capacity of 36,500,000 GPD and an average use of 14,000,000 GPD.[53]

Healthcare

[edit]Waterloo is home to two hospitals, Mercy One Waterloo Medical Center, which has 366 beds, and Unity Point Health Allen Memorial Hospital, with 234 beds. Neighboring Cedar Falls is home to Sartori Memorial Hospital, with 83 beds. The Waterloo-Cedar Falls metropolitan area has 295 physicians, 69 dentists, 52 chiropractors, 24 vision specialists and 21 nursing/retirement homes.[54]

Notable people

[edit]

- Julie Adams (1926–2019), actress[55]

- Jerome Amos Jr. (born 1954), politician[56]

- Michele Bachmann (born 1956), politician[57]

- David Barrett (born 1977), American football player

- William Birenbaum (1923–2010), educator[58]

- Horace Boies (1827–1923), politician[59]

- Bob Bowlsby (born 1952), athletics administrator

- Jack Bruner (1924–2003), baseball player

- Don Denkinger (1926–2003), baseball umpire

- Adam DeVine (born 1983), comedian, actor and writer

- Loren Doxey, physician and murderer[60][61]

- Pearlretta DuPuy (1871–1939), zither player and clubwoman[62]

- Rich Folkers (born 1946), baseball player and coach

- Travis Fulton (1977–2021), boxer and mixed martial artist

- Dan Gable (born 1948), wrestler and coach

- John Wayne Gacy (1942–1994), serial killer[63]

- Kim Guadagno (born 1959), politician[64][65]

- Mike Haffner (born 1942), American football player

- Nikole Hannah-Jones (born 1976), journalist[66]

- Lou Henry Hoover (1874–1944), First Lady[67]

- MarTay Jenkins (born 1975), American football player[68]

- Anesa Kajtazović (born 1986), politician

- Arthur Rolland Kelly (1878–1959), architect[69]

- Chris Klieman (born 1967), football coach,

- Bonnie Koloc (born 1946), singer-songwriter[70]

- John Hooker Leavitt (1831–1906), politician[71]

- Jason Lewis (born 1955), politician

- Jack Little (1899–1956), songwriter

- J. J. Moses (born 1979), American football player[72]

- Charles W. Mullan (1845–1919), politician[73]

- Larry Nemmers (born 1943), American football official[74]

- Thunderbolt Patterson (born 1941), professional wrestler

- Joe Pelton (born 1977), poker player

- Don Perkins (1938–2022), American football player

- Cal Petersen (born 1994), ice hockey player

- Gordon Randolph (1915–1999), journalist[75]

- Alfred C. Richmond (1902–1984), U.S. Coast Guard Admiral

- Mike Ritland, US Navy SEAL

- Gertrude Ina Robinson (1868–1950), harpist, composer and writer

- Reggie Roby (1961–2005), American football player[76]

- Zud Schammel (1910–1973), American football player[77]

- Sean Schemmel (born 1968), voice actor

- Duane Slick, (born 1961) painter and professor[78]

- Tom Smith (born 1949), football player

- Vivian Smith (1891–1961), suffragist

- Paul Sohl (born 1963), U.S. Navy Rear Admiral

- Tracie Spencer (born 1976), singer-songwriter[79]

- Darren Sproles (born 1983), American football player; running back for fifteen seasons

- Bradley Steffens (born 1955), writer[80]

- Suzanne Stephens (born 1946), clarinetist and basset horn player[81]

- Sullivan Brothers, soldier brothers[82]

- Corey Taylor (born 1973), musician

- Michael Townley (born 1942), agent

- Mike van Arsdale (born 1965), mixed martial artist

- Mona Van Duyn (1921–2004), poet[83]

- Emily West (born 1981), singer[84]

- Nancy Youngblut (born 1953), actress

- Pat McLaughlin (born 1950), singer-songwriter[85]

- Bruce B. Zager (born 1952), judge

Twin towns and sister cities

[edit]Waterloo is twinned with:

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Boesen originally served in one of the at-large seats until December 31, 2023. He was elected to the Ward 2 seat in the 2023 city elections, and took office on January 1, 2024.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Waterloo, Iowa

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "2020 Census State Redistricting Data". census.gov. United states Census Bureau. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "(H)our History Lesson: War Manufacturing in Waterloo, Iowa, World War II Heritage City (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved June 26, 2025.

- ^ "City Profile". public.iastate.edu. Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- ^ The History of Black Hawk County. Chicago: Western Historical Company. 1878. pp. 383 (pdf-375).

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.93.

- ^ "City Profile". Archived from the original on June 25, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Halpern, Rick; Horowitz, Roger (March 1, 1999). Meatpackers: An Oral History of Black Packinghouse Workers and Their Struggle for Racial and Economic Equality. NYU Press. ISBN 9781583670057.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Waterloo rallies to combat violence, racial divides". Des Moines Register. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Foster, Deborah (October 26, 2015). "The 10th Worst City for African Americans in the U.S. has a Story: This is How the Dream Derailed: The History of African Americans in Waterloo, Working at Rath, Where is Today's Local 46?". Medium. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Schumaker, Kathryn (2013). "The Politics of Youth: Civil Rights Reform in the Waterloo Public Schools". The Annals of Iowa. 72 (4): 353–385. doi:10.17077/0003-4827.1740.

- ^ a b c Jamison, Tim. "Report: Waterloo is Iowa's most segregated large city". Waterloo Cedar Falls Courier. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Writer, AMIE STEFFEN Courier Staff (September 9, 2007). "Waterloo race relations still an issue 40 years after city report". Waterloo Cedar Falls Courier. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Telegraph – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Wind, Andrew. "Vilsack looking to Waterloo in closing achievement gap for black males". Waterloo Cedar Falls Courier. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ "The Worst Cities For Black Americans". Huffington Post. October 6, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "City Data website". Waterloo-Iowa. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Kottek, M.; Grieser, J. R.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". USDA/Agricultural Research Center, PRISM Climate Group Oregon State University. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 30, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Waterloo Muni AP, IA". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 10, 2024. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for WATERLOO/WSO AP IA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 10, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Waterloo city, Iowa". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Waterloo city, Iowa". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Waterloo city, Iowa". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2020 Decennial Census: Waterloo city, Iowa". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Cumulative Estimates of Population Change for Metropolitan Statistical Areas and Rankings: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008". Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2009.

- ^ FOLEY, RYAN J. (May 5, 2020). "Nearly 1,400 Tyson workers at 3 Iowa plants get coronavirus". KGAN. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Leading Employers - Cedar Valley Regional Partnership". www.cedarvalleyregion.com. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Cedar Valley Arboretum & Botanic Gardens

- ^ "Top-Rated Waterpark in USA - Lost Island".

- ^ "VOLKANU - Quest for the Golden Idol Dark Ride | Sally Dark Rides".

- ^ Iowa Irish Fest

- ^ "Silos & Smokestacks National Heritage Area". Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Waterloo Center for the Arts/Directory". Waterloo Center for the Arts. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ "Local". Archived from the original on August 23, 2012.

- ^ "Excitement builds for Obama's Waterloo, Iowa, appearance | Iowa news". siouxcityjournal.com. August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Obama Stops For 'Just One' More Beer – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "The History of Our Theatre in Waterloo". WCP & BHCT. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ Eldridge, Mary Beth. "Brief Biographies of Early Residents of Waterloo, Black Hawk Co., Iowa". Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "The Grout Museum District". homepage. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ "Cate Blanchett in 'Carol': Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. May 16, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ "Waterloo Hawks Historical Statistics and All-Time Top Leaders".

- ^ "Waterloo Bucks".

- ^ "Waterloo" (PDF). Iowa Department of Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Cedar Falls" (PDF). Iowa Department of Education. Retrieved April 7, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jefferson Bus Lines discontinues service to Mason City".

- ^ Russell, Shelley (April 14, 2014). "Waterloo missing 851 million gallons of water". KWWL News. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ "Cedar Valley Alliance". Utilities. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ "Greater Cedar Valley Alliance". fact sheet 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ Fleig, Shelby (February 19, 2019). "Iowa-born actress Julie Adams, famous for 'Creature From the Black Lagoon,' dies at 92". Des Moines Register. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ "State Representative". Iowa Legislature. Retrieved May 18, 2024.

- ^ Condon, Patrick (January 6, 2011). "Waterloo native Bachmann of Minnesota tests Iowa presidential waters". WCF Courier. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Fox, Margalit. "William M. Birenbaum, College Leader, Dies at 87", The New York Times, October 8, 2010. Accessed October 10, 2010

- ^ "National Governors Association". Horace Boies. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ Ancestry.com

- ^ "Dr. Doxey's Body in River, Thought to Have Killed Self," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, page 1

- ^ Binheim, Max; Elvin, Charles A (1928). "Dupuy, Pearlretta (Mrs. Robert G.)". Women of the West; a series of biographical sketches of living eminent women in the eleven western states of the United States of America. p. 38. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Lohr, David. "Boy Killer: John Wayne Gacy". Crime Magazine. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "State of New Jersey". Office of the Lieutenant Governor. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ "BALLOT*PEDIA". Kim Guadagno. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ "Waterloo native wins Pulitzer Prize". May 4, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Anne Beiser (2000). An independent woman: the life of Lou Henry. Greenwood Press. pp. 5–9. ISBN 0-313-31466-7.

- ^ "National Football League". MarTay Jenkins. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ "PCAD – Arthur Rolland Kelly". pcad.lib.washington.edu. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ Van Matre, Lynn (December 4, 1988). "Bonnie Koloc". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "John H. Leavitt, History of Waterloo, Waterloo Public Library". Archived from the original on February 5, 2006.

- ^ "Houston Texans". JJ Moses Bio. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ "Judge Mullan Dies Thursday in Rochester", The Des Moines Register, March 9, 1919, pg. 1, 2

- ^ Sulivan, Jim (December 30, 2007). "Official notice: Nemmers ready to hang up his whistle". WCF Courier. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Boards at Ancestry

- ^ "Pro-Football-Reference". Reggie Roby bio. Archived from the original on November 24, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ^ "PRO-FOOTBALL Reference". Zud Schammel. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ American Indians and Popular Culture: Media, Sports, and Politics. Volume 1 of American Indians and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. 2012. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9780313379901.

- ^ "DiVA station". Tracie Spencer bio. Archived from the original on January 10, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ Robert L. Pincus (May 25, 2008). “Steffens takes top honor at book awards bash.” San Diego Union Tribune.

- ^ "Suzanne Stephens – Clarinet, Basset-Horn and Bass Clarinet". Stockhausen.org. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ John R. Satterfield, We Band of Brothers: The Sullivans & World War II (Parkersburg, IA: Mid-Prairie Books, 1995). ISBN 0-931209-58-7

- ^ "Mona Van Duyn (1921–2004)". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ Bialas, Michael (May 18, 2010). "Finally on the Road, Emily West Keeps 'Em Laughing, Crying". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 17, 2011.

- ^ Kinney, Pat (December 3, 2005). "Where Are They Now? Pat McLaughlin". The Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier.

- ^ "Waterloo (USA)". giessen.de (in German). Giessen. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Международни контакти". targovishte.bg (in Bulgarian). Targovishte. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Waterloo City Council tackles rezoning, sister city, neighborhood crime". kwwl.com. KWWL News. November 25, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

External links

[edit]- City website

- Waterloo Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Waterloo Chamber of Commerce

- City Data – comprehensive statistical data and more about Waterloo, Iowa

- Historic

KSF

KSF