Waterside Generating Station

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 17 min

| Waterside Generating Station | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Location | New York, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°44′48″N 73°58′14″W / 40.74667°N 73.97056°W |

| Status | Decommissioned |

| Commission date | No. 1: October 1901 No. 2: November 1906 |

| Decommission date | April 2005 |

| Owner | Consolidated Edison |

| Cooling source | East River |

| Cogeneration? | Yes |

| Power generation | |

| Nameplate capacity | 167 MW (2005)[1] |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

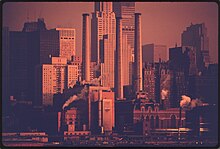

Waterside Generating Station was a power station in Manhattan, New York City, that opened in 1901 and was one of the first power plants in the United States that generated electricity using steam turbines. Built by the New York Edison Company, the facility was located in the Murray Hill neighborhood on the east side of First Avenue between East 38th and 40th streets, alongside the East River. The Waterside station also later served as a cogeneration facility and generated steam for the New York City steam system.

The power plant was decommissioned by Con Edison in 2005 and sold to private developers as part of the East River Repowering Project, which increased the capacity of the East River Generating Station at East 14th Street to replace the steam and electric output of the Waterside Generating Station. After demolition of the Waterside plant, the site underwent environmental remediation and was rezoned to allow for residential and commercial development. As of 2023, the property has remained vacant land.

History

[edit]Opening and early years

[edit]Before Waterside was constructed, there were several small power stations located in different parts of Manhattan that were interconnected through the electrical network to help distribute the demand for power. This system was reaching its capacity and there was a desire to create a large new plant that could generate nearly all of the electricity that was needed whereas the smaller power stations could be retained to provide supplemental generating capacity during periods of heavy loads but would primarily function as substations to distribute the power produced by the new plant.[2]

In the late 1890s preliminary plans were made by the Edison Electric Illuminating Company (a predecessor of the New York Edison Company) for a large power plant along the waterside and land was purchased for such a facility, but the company decided to make further investigations before embarking on construction. In 1898, a team consisting of John W. Lieb, John Van Vleck, and Arthur Williams visited power plants in Europe and consulted with experts in the field. The plans for the Waterside power plant were modified, submitted to the Building Department in January 1900, and completed under the supervision of Thomas E. Murray.[3][4]

Waterside No. 1, which was located between East 38th and 39th streets, began operations in October 1901.[5] Electric power was initially generated in the form of 6,600-volt, three phase, 25-cycle alternating current by a combination of reciprocating steam engines and steam turbines. Waterside was originally intended to house a total of sixteen reciprocating steam engines, but as the plant was designed significant advances were being made in the development of steam turbines so that only eleven reciprocating steam engines were installed and the remainder of the space was used for the installation of five steam turbines.[6] Waterside was one of the first power plants in the United States to produce electricity using steam turbines.[7] The electricity was transmitted to substations that converted it to direct current using rotary converters so it could be used in Manhattan's existing low voltage direct current distribution network.[6]

The Waterside plant was originally designed to accommodate the projected demand for the electricity that would be needed from customers until 1910, but during construction of the facility it was determined that this limit would instead be reached by 1905. For this reason, land was purchased on the north side of the power plant between East 39th and 40th streets to develop a second unit, Waterside No 2., which began operations in November 1906.[5][8][9] The Waterside No. 1 and Waterside No. 2 stations were connected to each other both electrically and mechanically.[8][9] While Waterside No. 1 only supplied electricity within Manhattan, the addition of Waterside No. 2 allowed the plant to also provide power to parts of the Bronx, Queens, and Westchester. In 1911, the rated capacity of Waterside No. 1 was 157,000 kilowatts and the rated capacity of Waterside No. 2 was 140,000 kilowatts.[10]

The location of the plant alongside the East River allowed coal to be transported to the facility via barge. Conveyors belts and hoists were used to move the coal from the bulkhead into coal bunkers, which could store enough coal to fuel the boilers in the plant for two weeks. Ashes from the boilers were brought to the dock in a similar manner of conveyors and hoists for loading onto barges for removal.[11][12]

In the 1920s, the Waterside facility was expanded to the north with the addition of an office building, switch house, and frequency house on the block between East 40th and 41st streets. The frequency house, which was known as the Waterside Tie Station, contained frequency changers to convert power between the original 25-cycle system and the newer 60-cycle system used for alternating current.[6][13]

The New York Edison Company became Consolidated Edison in 1936.[14] In 1937, advances in technology allowed steam that had passed through the turbines to be subsequently distributed to customers, making Waterside an early plant to use cogeneration.[7] The combined capacity of Waterside No. 1 and Waterside No. 2 was over 370 MW in 1940.[6]

In May 1942, the segment of the East River Drive from East 34th to 49th streets opened to traffic, which was constructed between the eastern edge of the power plant and the East River. A total of $3,500,000 was spent by Con Edison making changes to the coal and ash conveyor systems for Waterside station to permit the construction of the highway.[15][16]

Smoke concerns at United Nations

[edit]

During construction of the headquarters of the United Nations, which then was being developed on the east side of First Avenue between East 42nd and 48th streets, concerns about smoke and gases from the Waterside plant affecting the Secretariat Building were raised by Secretary-General Trygve Lie. In August 1950, New York City Mayor William O'Dwyer wrote to President Harry S. Truman asking if Con Edison's share of natural gas that would be carried in the Transcontinental Gas Pipeline (Transco) could be increased so that the Waterside plant could be converted from coal to natural gas to use a smokeless fuel, but the President turned down the request after receiving a report from Mon C. Wallgren, chairman of the Federal Power Commission (FPC).[17]

The FPC said the smoke would not present a danger to health, but acknowledged that certain gases were a nuisance and recommended that the air conditioning system for the Secretariat Building include "washers" to remove obnoxious gases from the smoke. They also suggested that the smokestacks of the plant, which were 75 feet (23 m) lower than the Secretariat Building, be raised using a "towering stack" but recognized that a higher smokestack could be a hazard to aircraft.[18][19]

Con Edison planned to make other improvements to smoke control at Waterside No. 2 in 1951 by installing mechanical fly ash collectors in advance of the existing electrostatic precipitators.[20] The purchase of equipment was delayed by a year by the Defense Electric Power Administration, which turned down the application to give priority to other projects that would provide additional electric power to serve defense plants because of a shortage of materials.[21][22]

In November 1959, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled that the FPC could not ban Con Edison from purchasing an allotment of natural gas in Texas and having it transported by Transco to fuel two of the plant's ten boilers.[23] However, this decision was overturned in January 1961 by the Supreme Court of the United States.[24]

By 1963 the Waterside plant was partially running on natural gas, but only for about 60 percent of the days in the year because of limits in the capacity of the pipeline that transported the gas to New York City.[25]

Late 20th century

[edit]

On the evening of November 10, 1992, a 24-inch (61 cm) steam pipe ruptured at the power station, causing an explosion that killed one worker and injured seven other people, five of which were firefighters that came to the plant to search for trapped workers. Steam distribution to Manhattan was not affected by the incident, as Con Edison rerouted steam from other plants to bypass the Waterside facility while it was shut down.[26][27] An investigation by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) found that the explosion was caused by a water hammer that formed when new steam was introduced to pipes that had not been properly drained out.[28] Con Edison was fined $217,800 by OSHA for violating worker safety rules that resulted in the accident.[29]

Decommissioning and sale

[edit]In 1999, Con Ed announced plans to sell the site of the Waterside plant to private developers along with three other properties along First Avenue near the plant that had been placed on the market the previous year.[30] This came as a result of the company's long-range plan for its steam system and a deregulation agreement reached with the New York Public Service Commission (PSC).[31] To replace the loss of the steam and electric output of the Waterside Generating Station, new equipment was proposed to be added inside an unused section of the East River Generating Station at East 14th Street to "repower" the facility and increase its capacity; this plan was referred to as the East River Repowering Project (ERRP).[32][33]

More than 20 bids for the four properties were submitted to Con Edison. The winning bid was submitted by a development team that included Sheldon Solow and the Fisher Brothers with backing from Morgan Stanley Dean Witter & Co.[30] The development team entered into a contract to purchase the properties from Con Edison in 2000. The sale process required regulatory approval from the PSC to demolish the Waterside plant and expand the capacity of the East River plant as well as approval from the city to rezone the land for residential and commercial development.[34]

The PSC initially approved the expansion of the East River plant and closure of the Waterside plant in August 2001, but later agreed to hold more hearings to assess the effects of the plant expansion on PM2.5 after receiving a petition from New York State Assemblyman Steven Sanders, Manhattan Community Board 3, and the New York Public Interest Research Group.[35][36][37] Con Ed reached an agreement addressing the air pollution concerns of residents near the East River plant and environmental groups in March 2002.[37] The sale of the Waterside plant and the three other Con Edison properties was ultimately approved by the PSC in 2004.[38]

Work on the ERRP was completed in April 2005, when the new equipment at the East River plant was placed into service and the Waterside plant was decommissioned.[1] Before its decommissioning, the Waterside plant had been the oldest operating electric power generating station in New York City.[39] Con Edison closed on the sale of the Waterside plant and the three other First Avenue properties in March 2005 and May 2005.[40] Demolition and environmental remediation of the properties was completed in 2008.[41]

Redevelopment

[edit]

In 2008, a rezoning of the Waterside site and the three other former Con Edison properties along First Avenue was approved by the New York City Planning Commission and the New York City Council.[42][43] The three other Con Edison parcels that had been included in the sale and rezoning included the former Kips Bay Generating Station on the east side of First Avenue between East 35th and 36th streets, a former parking lot on the west side of First Avenue between East 39th and 40th streets, and a former office building on the east side of First Avenue between East 40th and East 41st streets.[44]

The former site of the Kips Bay Generating Station was sold by Solow and redeveloped with an elementary school that opened in 2013 and a pair of residential skyscrapers, American Copper Buildings, that were completed in 2017 and 2018.[45][46] The former site of the parking lot at 685 First Avenue was redeveloped by Solow with a 43-story residential skyscraper that was designed by Richard Meier and opened in 2019;[47] Meier was previously involved with developing a master plan for the former Con Edison sites in 2008, which his firm updated in 2012.[48]

The former pier of the Waterside Generating Station along the East River between 38th and 41st streets was opened to the public in October 2016 and now forms part of the East River Greenway.[49] As of 2023, the blocks on the east side of First Avenue between East 38th and 41st streets—including the former site of the Waterside plant—remain vacant. Solow died in November 2020 and left the property to his son Stefan Soloviev.[50] The property was labeled as "Freedom Plaza" on Google Maps.[51] A temporary art installation, Field of Light, by Bruce Munro, opened on the former site of the power plant in December 2023.[52][53] In February 2024, Bjarke Ingels Group proposed redeveloping the site as Freedom Plaza, which was to contain a casino, a museum, restaurants and bars, two residential towers, and two 615-foot (187 m) hotel towers connected by a cantilevered skybridge.[51][54]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Con Edison 2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Con Edison. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Sheardown, P. S. (December 9, 1904). "Description of Electric Light and Power Schemes in New York, with Special Reference to the Waterside Station of the New York Edison Company". The Electrical Engineer. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Edison Company's New Power House". The New York Times. January 14, 1900. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ New York Edison Company 1913, pp. 115, 135.

- ^ a b United States Bureau of the Census (1907). Central Electric Light and Power Stations. p. 97. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d Blalock, Thomas (2003). "The Waterside Generating Stations of the New York Edison Company" (PDF). Society for Industrial Archeology New England Chapters Newsletter. Vol. 23, no. 2. pp. 12–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b King, Martin (December 24, 1981). "To the man who lights up your life". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on February 16, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Murray 1910, p. 39.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas Commerford (1922). Forty Years of Edison Service, 1882-1922. New York Edison Company. p. 105. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ New York Edison Company 1913, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Murray 1910, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Murray 1910, pp. 51–61.

- ^ "Brownfield Cleanup Program – Citizen Participation Plan for Greater Waterside Site" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. April 6, 2011. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "To Add Bronx Gas and N.Y. Edison". The New York Times. July 15, 1936. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "East River Drive Is Opened In Full". The New York Times. May 26, 1942. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Open Last Link of East River Drive". Daily News. New York. May 26, 1942. Archived from the original on February 16, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Truman Rejects City's Plea on Gas". The New York Times. August 5, 1950. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "'Air Wash' Sought for U.N. Building". The New York Times. September 19, 1950. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Utility Sidesteps U.N. Plea on Smoke". The New York Times. September 24, 1950. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Edison Smoke Curb To Cost $3,739,500". The New York Times. December 9, 1951. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Agency Delays Edison Smoke Plan". The New York Times. December 20, 1951. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Edison Gets Signal for Smoke Devices". The New York Times. April 18, 1952. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Con Edison Wins Natural Gas Suit". The New York Times. November 6, 1959. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Con Edison Loses on Gas for Plant". The New York Times. January 24, 1961. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Cook, Fred J. (December 29, 1963). "Murk, Smog, Smoke—Needed: Fresh Air". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Steinberg, Jacques (November 11, 1992). "Pipe Ruptures And Rocks Con Ed Plant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Mangaliman, Jessie (November 13, 1992). "Feds to Begin Inspection Of Shut-Down Con Ed Plant". Newsday. Archived from the original on February 16, 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (May 7, 1993). "U.S. Blames Con Ed Error For Fatal Plant Explosion". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (April 4, 1995). "Con Edison Penalized $217,800 for Violating Work Safety Rules in '92 Blast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Grant, Peter (December 31, 1999). "Con Ed to Sell Big New York Site To Local Group of Developers". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Serant, Claire (August 20, 1998). "Breaking Up Con Ed Utility Preparing to Sell Off Property". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Con Edison Holds Public Forum on Power Plant Changes" (Press release). Con Edison. September 1, 1999. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Con Edison Files Application to Repower Steam Station" (Press release). Con Edison. June 1, 2000. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (November 29, 2000). "Developers to Buy 9.2 Acres on East Side". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Manhattan Power Plant Expansion Gets NY OK". Newsday. Associated Press. August 29, 2001. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Rose, Derek; Katz, Celeste (January 28, 2002). "Hearings on Con Ed East River plant emission fears to be aired". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Blair, Jayson (March 16, 2002). "Con Ed Agrees to Pay for Cleaner Air Near Power Plant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "NYS PSC Approves Transfer of Con Edison Properties in Manhattan" (Press release). New York Public Service Commission. May 19, 2004. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (April 8, 1990). "What Really Makes New York Work: The Infrastructure; The Body and Soul of the City Machine". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Burke, Kevin (September 28, 2005). Con Edison, Inc. - Solid, Steady, Straightforward (PDF). Merrill Lynch Global Power and Gas Leaders Conference. New York, NY. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Waterside Generating Station Demolition and Abatement". TRC Consulting. January 1, 2019. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Freedlander, David (January 29, 2008). "Critics slam project near UN". Newsday. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Bagli, Charles V. (March 13, 2008). "Plan for Ambitious East Side Project Clears Big Hurdle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "First Avenue Properties Rezoning Final SEIS" (PDF). January 2008. p. 1-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Holland, Heather (September 9, 2013). "New Murray Hill Elementary School Welcomes First Students". DNAinfo. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Lipson, Karin (December 15, 2021). "Murray Hill, Manhattan: Flush With History, Now 'Seeing a Transformation'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Young, Michael (January 16, 2019). "Leasing Launches For Solow's 685 First Avenue In Midtown East, Manhattan". New York Yimby. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Doge, Annie (April 9, 2018). "Richard Meier's East side master plan moving ahead with three condos and biotech offices". 6sqft. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "NYC Parks Debuts Redesigned Waterside Pier on Manhattan's East Side" (Press release). New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. October 25, 2021. Archived from the original on July 20, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Small, Eddie (June 4, 2021). "Sheldon Solow discourages selling his properties in will–with one notable exception". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Roche, Daniel (February 12, 2024). "BIG unveils a megaproject next to the UN". The Architect’s Newspaper. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Chen, Stefanos (May 10, 2023). "Will This Light Show Help a Bid for a Coveted New York Casino License?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ Ginsburg, Aaron (December 15, 2023). "Free six-acre light installation 'Field of Light' opens in Midtown East". 6sqft. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ Choi, Christy (February 15, 2024). "New York's Freedom Plaza development will feature skyscrapers joined by daring cantilevered 'skybridge'". CNN. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Murray, Thomas Edward (1910). Electric Power Plants. New York. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thirty Years of New York, 1882-1892. New York Edison Company. 1913. Retrieved June 20, 2023 – via Google Books.

Further reading

[edit]- Blalock, Thomas J. (November–December 2017). "Operating Waterside: Interesting Facts About How It Was Done". IEEE Power and Energy Magazine. Vol. 15, no. 6. pp. 94–108. doi:10.1109/MPE.2017.2729198.

- David, Robert (2007). The History of the Waterside Generating Station 1901 – 2005. Consolidated Edison of New York. ISBN 9780615157238.

External links

[edit] Media related to New York Edison Company Powerhouse, 686-700 First Avenue, New York City at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to New York Edison Company Powerhouse, 686-700 First Avenue, New York City at Wikimedia Commons- Con Edison's East River Repowering Plan

KSF

KSF